Special issue on hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and hepatitis B and C as its main causes worldwide

More infoIdentification of asymptomatic hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) carriers is fundamental to reach the World Health Organization objective to eradicate viral hepatitis. The aim of this study was to evaluate the HBV and HCV prevalence among patients hospitalized for a non-liver-related disease but showing increased liver enzyme values.

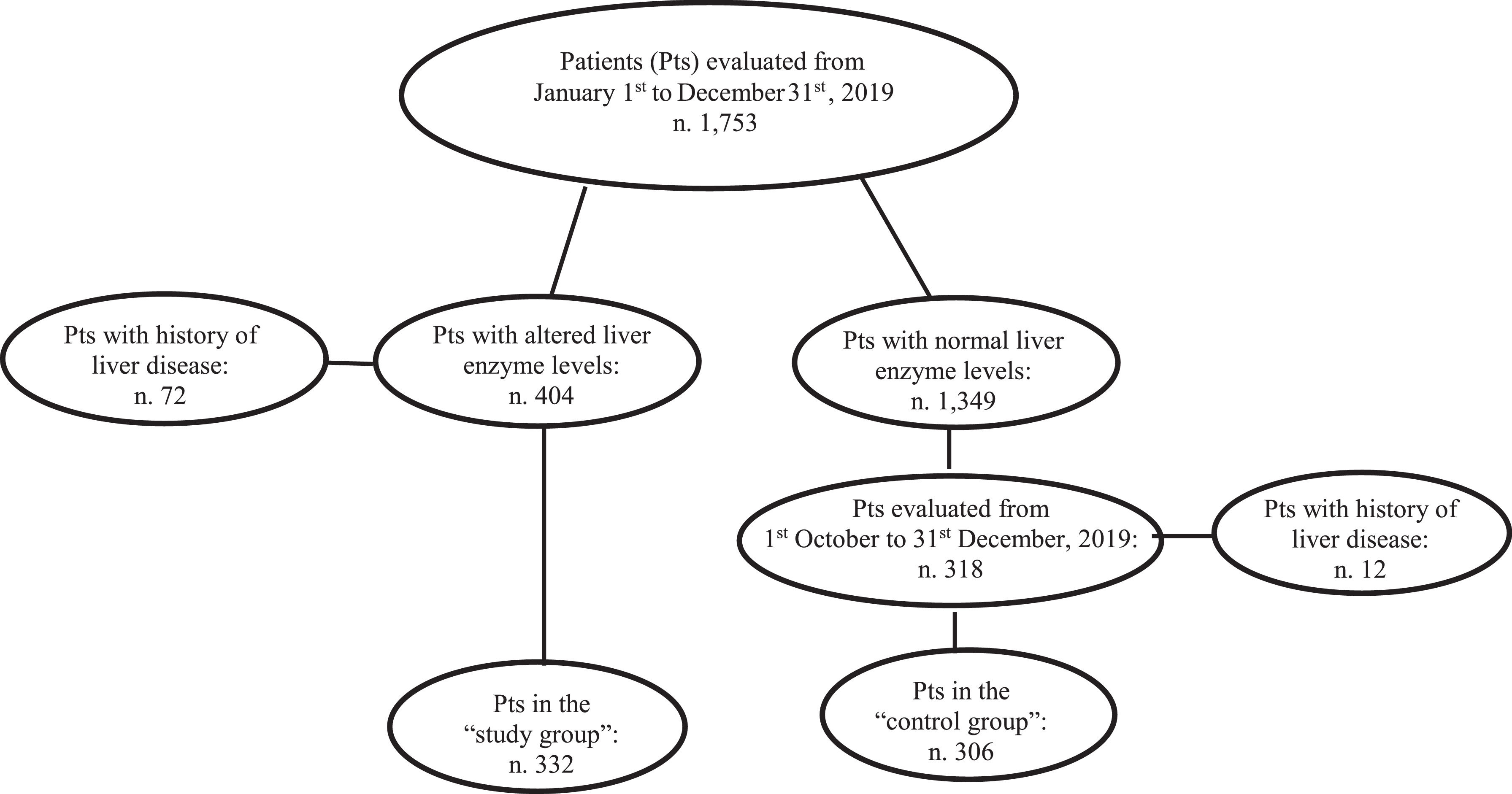

Patients and methodsAll consecutive patients without history of hepatic disease but showing increased amino-transferase and/or gamma-glutamil-transpeptidase levels at admission to the Internal Medicine and Surgery divisions of the Messina University Hospital from 1st January to 31st December 2019 (“study group”) were tested for HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) and anti-HCV antibody. Analogously, HBsAg and anti-HCV were tested for in all the individuals with normal liver enzyme values consecutively admitted from October 1st to December 31st, 2019 (“control group”).

ResultsOf the 332 “study group” patients, 13 (3.9%) were anti-HCV positive versus 5/306 (1.6%) patients of the “control group” (p=0.008). HCV RNA was detected in 11/13 and in 0/5 anti-HCV patients of the “study group” and “control group”, respectively (p=0.001). HBsAg was detected in 5 (1.5%) “study group” patients and in none of the “control group” (p=0.03). Prevalence of diabetes, arterial hypertension, and dyslipidaemia was comparable between the two groups, whereas 75/332 (22.3%) patients of the “study group” and 34/306 (11.1%) patients of the “control group” drank > 2 alcohol units/day (p < 0.001).

ConclusionTesting HBsAg and anti-HCV in subjects showing increased liver enzyme values may represent an efficacious tool to identify asymptomatic carriers of hepatitis virus infections.

Chronic viral hepatitis is a leading cause of worldwide liver-related morbidity and mortality [1,2] Therefore, in 2016 the World Health Organization (WHO) included the eradication of viral hepatitis by 2030 among the prioritized public health objectives [3–5]. This goal may theoretically be achievable given the progress obtained in the prevention and treatment of hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections [6–9]. In this direction, significant results have been obtained due to the spread of the HBV vaccine, the existing anti-HBV treatments, and the availability of new direct acting antiviral (DAA) drugs against HCV, which are able to definitively cure this viral infection in almost all treated patients [10–14].

However, considering that a large number of chronically infected individuals can remain asymptomatic for decades and are not aware of their status, an essential step in reaching the above-mentioned WHO objective is the development of screening strategies that may allow for an increased number of HBV and HCV diagnoses [15–17]. In this context, the strategies for viral identification that have been adopted so far to screen populations at risk of infection (i.e., drug addicts, men who have sex with men, prisoners, sex workers) are still not sufficient to identify a large part of asymptomatic HBV and HCV carriers, and therefore should be implemented.

Elevated serum liver enzyme values represent the most used surrogate marker of liver injury in clinical practice [18]. A recent study reported that among subjects attending general practitioners (GPs) surgeries in the city of Messina (Sicily, Italy), 20.5% had abnormal liver enzyme levels, and among them 6.8% were HCV and/or HBV positive, many of whom were unaware of being infected [19]. Thus, we postulated that the evaluation of liver biochemistry might represent an important first step in the identification of HCV and/or HBV positive patients who have no known risk factors of infection.

On this basis, the aims of this study were to investigate liver enzyme levels and prevalence of HBV and HCV infections in consecutive patients without history of hepatic disorders, hospitalized at the Internal Medicine and Surgery divisions of the Messina University Hospital for causes unrelated to liver diseases.

2Patients and methodsThe Internal Medicine (IM) and Emergency Surgery (ES) divisions of the University Hospital of Messina admit patients who originally attended the Hospital Emergency Room. All these patients routinely undergo hematochemical and biochemistry tests at the time of hospitalization, which also include evaluation of blood cell counts, kidney function tests, liver biochemistry [alanine-amino-transferase (ALT), aspartate-amino-transferase (AST), gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase (gGT) values], international normalized ratio, albuminemia, glycemia, and creatine phosphokinase (CPK) values. The design of this study foresaw the enrolment of all patients consecutively admitted to the previously mentioned two units from January 1st to December 31st 2019 and who showed increased levels of AST and/or ALT and/or gGT. Exclusion criteria were history of liver disease and/or of acute viral hepatitis, admission to the hospital for obstruction/occlusion of the biliary tree, increased CPK values (normal values of AST, ALT, gGT, and CPK at the hospital laboratory evaluations, ≤ 40 U/L, ≤ 40 U/L, ≤ 50 U/L, ≤ 200 U/L, respectively). All the enrolled patients (“study group”) underwent additional blood tests, including examination of HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) and antibody to HCV (anti-HCV) as well as cholesterolemia and trigliceridemia values. All these data together with information concerning lifestyle, physical examination, presence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), of arterial hypertension, and of dyslipidemia (i.e., increased levels of cholesterolemia and/or triglyceridemia) as well as any possible concomitant pharmacological treatment were reported for each patient in a digitalized dataset. Drinking habits were also investigated, and alcohol intake was quantified as the number of units drunk [one drink or alcoholic unit (AU) = 12.5 g of pure ethanol contained in a glass of wine, a pint of beer, or a mini-glass of spirits] [20]. The subjects were thus classified according to the amount (less or more than 2 AU/day) of alcohol consumed.

Finally, all the patients with normal AST, ALT, and gGT values admitted to those two divisions from Octuber 1st to December 31st 2019 were tested for HBsAg and anti-HCV and represented the “control group”.

The study was approved by the ethical committee of the district of Messina and all patients signed informed consent.

2.1Statistical analysisThe numerical data were expressed as median and range (minimum and maximum) and the categorical variables as number and percentage.

The non-parametric approach was used since most of the numerical variables were not normally distributed, such as verified by Kolmogorov Smirnov test. The existence of significant differences between “Study Group” and “Control Group” patients was evaluated using Mann Whitney test (for numerical parameters) and Chi Square test or exact Fisher test or Likelihood ratio test, as appropriate (for categorical variables).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 for Windows package.

A p-value lower than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

3ResultsOne-thousand-seven-hundred and fifty-three consecutive patients were prospectively admitted to the Internal Medicine [906 (51.7%) patients] and Emergency Surgery [847 (48.3%) patients] Divisions of the Messina University Hospital from January 1st to December 31st, 2019.

At admission, 404/1,753 (23%) patients had increased values of AST and/or ALT and/or gGT. Seventy-two (17.8%) of the 404 had a previous diagnosis of liver disease and were excluded from the analysis. The remaining 332 (82.2%) patients had no history of liver disease becoming the “study group”. They were investigated for HBsAg and anti-HCV. Among the 332 individuals with altered liver enzymes, ALT levels were increased in 211 (63.5%), AST in 215 (64.7%) and gGT in 268 (80.7%) subjects. In particular ALT levels were lower than one time the normal value (NV) in 128/211 (60.6%) cases, between one and two times the NV in 39/211 (18.5%) cases, and higher than two times the NV in 44/211 (20.8%) cases. AST levels were lower than one time the NV in 114/209 cases (54.5%), between one and two times in 41/209 (19.6 %) cases, and higher than two times in 54/209 (25.8 %) cases. gGT levels were lower than one time the NV in 122/268 cases (45.5%), between one and two times in 68/268 (25.4%), and higher than two times the NV in 78/268 (29.1%) cases. One-hundred and eight of 332 (32.5%) subjects had all three liver enzyme levels increased, 79/332 (23.8%) had two of the three levels increased, and 145/332 (43.7%) had only one of the three levels increased.

During the last three months of the study period (from October 1st to December 31st, 2019), 318 patients with normal AST, ALT, and gGT values were consecutively admitted to the above-mentioned divisions. Twelve (3.7%) of these patients had a history of liver disease and were excluded from the study. The remaining 306 patients were enrolled as the “control group” and underwent the same analyses performed in the “study group” including HBsAg and anti-HCV (Fig. 1).

Of the 332 patients with altered liver enzymes [189 male (56.9%) ; median age 71 range 20-99 years)], 84 (25.3%) had T2DM, 89 (26.8%) had arterial hypertension, and 187 (67%) had dyslipidaemia. Two hundred and forty-one (76.3%) were teetotal or drinkers of less than 2 AU /day. Five (1.5%) were HBsAg positive, and 13 (3.9%) were anti-HCV positive (Table 1). All HBsAg and anti-HCV positive patients were tested for HBV DNA and HCV RNA, respectively, and then referred to the out-patient clinic of the liver unit of the hospital for further evaluation and possible treatment. Of note, 11/13 anti-HCV positive individuals were HCV-RNA positive (8 cases were genotype 1b infected, 2 cases genotype 2, 1 case genotype 3), and 2/13 were HCV RNA negative (Table 1). Neither HBsAg nor anti-HCV positivity was associated with the grade of ALT, AST, and gGT increase nor with alteration of one, two or all three liver enzyme levels (p=0.5, p=0.8, respectively).

Characteristics of 332 patients with increased liver enzyme values (study group) and 306 patients with normal liver enzyme levels (control group).

Bold characters identify statistically significant variables.

Abbreviations: n (number of cases); HCV (Hepatitis C virus); HBsAg (Hepatitis B surface antigen).

Two-hundred and twenty-seven of the 332 (68.4%) patients of the “study group” had been admitted to the IM and 105 (31.6%) to the ES divisions. Among the 227 patients admitted to the IM division, [123 (54.2 %) male; median age 68 years (range 20–103 years)] the main causes of hospitalization were heart failure (66 patients, 29.1%), acute metabolic imbalance (45 patients, 19.8 %), acute respiratory disease (47 patients, 20.7%), severe anaemia (41 patients, 18.1%), and fever (28 patients, 12.3%). Concerning the 105 patients admitted to the ES division, [66 male(66.8%); median age 68 years (range 23-98 years)], the causes of hospitalization were intestinal occlusion or bleeding (42 patients, 38.1%), complicated inguinal or abdominal hernia (28 patients, 27.6%), acute appendicitis (16 patients, 13.3%), bleeding gastric or duodenal ulcers (11 patients, 8.6%), and abdominal trauma (9 patients, 9.1%). Comparing the IM and ES hospitalized patients, no statistically significant differences concerning sex, arterial hypertension, T2DM, dyslipidaemia, HBsAg and anti-HCV positivity were observed. On the contrary, patients admitted to the ES division were significantly younger and showed lower amount of alcohol intake (p=0.026 and p < 0.001, respectively), whereas AST, ALT, and gGT values were significantly higher in patients admitted to the IM division (p=0.001, p=0.03, p=0.04, respectively).

Concerning the 306 control group patients [141 male (46.1%); median age 87 (range 18–99 years)], 90 (29.4%) had T2DM, 94 (30.7%) arterial hypertension, and 155 (50.6%) dyslipidaemia. Two hundred and seventy-two (88.9%) were teetotal or drank less than two UA/day, and 34 (21.1%) drank more than two UA/day. No patients were HBsAg positive, whereas 5 patients (1.6%) were anti-HCV positive. Notably, all these cases were HCV RNA negative. Comparing patients in the “study group” and the “control group”, there were no statistically significant differences concerning age, arterial hypertension, T2DM, dyslipidaemia, and anti-HCV positivity. On the contrary, male sex, drinking habits, HBsAg and HCV RNA positivity were significantly associated with altered liver enzyme values (p=0.006, p=< 0.001, p=0.03, p=0.001, respectively). Two hundred and nineteen [101 males; median age 78 years (range 18–99 years)] of the 306 (71.6%) “control group” subjects had been admitted to the IM division, and 87 [40 males (28.4%); median age 76 years (range 30–87 years)] had been admitted to the ES division. In the IM group, the causes of hospitalization were heart failure in 58 (26.5%) patients, acute metabolic imbalance in 58 (26.5%), acute respiratory disease in 27 (12.3%), severe anaemia in 53 (24.2%), and fever in 23 (10.5%). Among the 87 patients admitted to the ES division, 40 were males, 47 females; median age was 76 years (range 30–87 years). In this group, the causes of hospitalization were intestinal occlusion or bleeding in 36 (41.4%) cases, acute appendicitis in 22 (25.3%) cases, complicated inguinal or abdominal hernia in 14 (6.9%) cases, bleeding gastric or duodenal ulcer in 9 (10.3%) cases, and abdominal trauma in 6 (6.9%) cases. Comparing IM and ES patients, no statistically significant differences concerning age, sex distribution, arterial hypertension, T2DM, and alcohol intake were found, whereas dyslipidaemia was significantly associated with admission to the IM division (p=0.02) Tables 1–3.

Comparison of 227 patients with increased liver enzyme values admitted to the Internal Medicine (IM) and 105 patients admitted to the Emergency Surgical (ES) divisions.

All numerical parameters are expressed as median and range except for those otherwise indicated.

Bold characters identify statistically significant variables.

Abbreviations: n (number of cases); ALT (alanine aminotransferase); AST (aspartate aminotransferase); gGT (gamma glutamyl transpeptidase); HCV (Hepatitis C virus); HBsAg (Hepatitis B surface antigen).

Characteristics of 219 patients with normal liver enzyme values admitted to the Internal Medicine (IM) and 87 patients admitted to the Emergency Surgical (ES) divisions.

Bold characters identify statistically significant variables.

Abbreviations: n (number of cases); HCV (Hepatitis C virus); HBsAg (Hepatitis B surface antigen).

This study shows that increased values of liver enzymes are a reliable marker for identifying HBV and HCV individuals unaware of their status of infection. Considering this fact, testing for HBsAg and anti-HCV all subjects with increased AST, ALT and/or gGT levels admitted to hospital for non-liver related causes may represent an efficacious tool to find asymptomatic carriers of hepatitis virus infections, who may subsequently undergo proper antiviral therapy. Of note, all five anti-HCV positive subjects with normal liver enzyme values were HCV RNA negative, thus showing that the detected antibody positivity indicated a past and resolved infection. Furthermore, none of the patients with normal liver biochemistry were HBsAg positive. Therefore, chronic hepatitis virus infections are commonly associated with alteration of liver enzymes in subjects unaware of their positive liver disease status, at least in this series of patients tested for HBsAg and anti-HCV for research purposes. Of note, this observation confirms previous data on HBV and HCV prevalence obtained by examining patients with increased liver enzymes levels attending GPs surgeries in the same geographical area [12]. Actually, among the 5 HBsAg and the 11 HCV RNA positive subjects with increased aminotransferase and/or gGT, 3 HBsAg positive and 3 HCV RNA positive drank more than 2 AU/day. Thus, the abnormal enzyme levels might also be due to the excessive alcohol intake, in addition to the viral infections. From the clinical point of view, however, this consideration only apparently limits the relevance of the observation since antiviral therapies are recommended to be promptly started in all subjects with additional causes of liver disease, such as alcohol abuse.

Indeed, if it is not surprising that active HBV and HCV infections and excessive alcohol intake were found to be associated with increased values of liver enzymes, the lack of association of such an increase with T2DM and dyslipidaemia was quite unexpected. A possible explanation might be that most of the diabetic and dyslipidemic patients were under proper treatments at the time of hospitalization, which may also have had a positive effect in limiting or avoiding the liver injury provoked by the metabolic disorders.

In conclusion, this study prospectively evaluating a large number of patients consecutively admitted to hospital for non-hepatic diseases showed that the prevalence of active HBV and HCV infections is still quite relevant in the subset of individuals with abnormal liver enzyme levels. Thus, increase of aminotransferase and/or gGT values over the normal levels is a valid tool in the identification of individuals with unknown hepatitis virus chronic infections. Consequently, testing HBV and HCV serum markers in subjects showing abnormal liver biochemistry at routine evaluation should be included among the screening strategies to be adopted to achieve the WHO objective of the elimination of viral hepatitis by 2030 in the largest possible parts of the world [21–23].

The study was supported in part by the grant “Gilead - Fellowship-program N ID 04127” and in part by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Health (“Progetto ricerca finalizzata”, Grant No. RF-2016-02362422).