Serum hepatitis B virus (HBV) DNA level is a predictor of the development of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B patients. Nevertheless, the distribution of viral load levels in chronic HBV patients in Brazil has yet to be described. This cross-sectional study included 564 participants selected in nine Brazilian cities located in four of the five regions of the country using the database of a medical diagnostics company. Admission criteria included hepatitis B surface antigen seropositivity, availability of HBV viral load samples and age ≥ 18 years. Males comprised 64.5% of the study population. Mean age was 43.7 years. Most individuals (62.1%) were seronegative for the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg). Median serum ALT level was 34 U/L. In 58.5% of the patients HBV-DNA levels ranged from 300 to 99,999 copies/mL; however, in 21.6% levels were undetectable. Median HBV-DNA level was 2,351 copies/mL. Over 60% of the patients who tested negative for HBeAg and in whom ALT level was less than 1.5 times the upper limit of the normal range had HBV-DNA levels > 2,000 IU/mL, which has been considered a cut-off point for indicating a liver biopsy and/or treatment. In conclusion, HBV-DNA level identified a significant proportion of Brazilian individuals with chronic hepatitis B at risk of disease progression. Furthermore, this tool enables those individuals with high HBV-DNA levels who are susceptible to disease progression to be identified among patients with normal or slightly elevated ALT.

Despite the fact that chronic hepatitis B (CHB) is a preventable disease, more than 2 billion people around the world are infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and more than 350 million people have chronic hepatitis B.1 Patients with chronic hepatitis B are at an increased risk of developing cirrhosis of the liver and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).2 Moreover, there is recent evidence indicating a relationship between the development of these complications and baseline HBV-DNA level.3,4 With regard to progression to cirrhosis, the Risk Evaluation of Viral Load Elevation and Associated Liver Disease/Cancer-Hepatitis B Virus (REVEAL-HBV) study found that the cumulative incidence of liver cirrhosis increased as a function of HBV-DNA levels, ranging from approximately 5% when viral load was undetectable (< 300 copies/mL) to 36% with ≥ 106 copies/mL irrespective of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) status.3 Similar results have been reported with respect to the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma. Cumulative incidences were 1.3% with < 300 copies/mL and 14.9% with ≥ 106 copies/mL. HBV-DNA levels were significantly associated with the risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma (p < 0.001).4

The true prevalence of CHB in Brazil is unknown. Data from the Brazilian Ministry of Health indicate that at least 1% of the population is chronically infected with HBV,5 particularly in the major urban areas; however, there is a distinct risk of underestimation. Many regional studies have been carried out to evaluate the prevalence of the disease, but none on a nationwide scale.6-9 The majority of these findings are derived from studies conducted in small communities, specific population groups or blood-bank samples.10-14 These studies indicate that there are areas of high endemicity in which the prevalence of chronically ill hepatitis B patients ranges from 8% to 25%, while the prevalence of anti-HBs positivity is 60-85%. The areas in which prevalence is higher are typically found in the Amazon region in the north of the country. Areas with intermediate HBV prevalence in which the rate of chronic carriage ranges from 2% to 7% are located in the western part of the state of Santa Catarina and in southwest Paraná in the south of the country and in the state of Espírito Santo in the southeastern region of Brazil. Finally, most of the regions of the country, including the state capital cities, are known to be areas of low endemicity in which the prevalence of chronic patients is below 2%. In contrast with the genotypes identified in Asian countries, A, D and F are the genotypes most frequently found in Brazil, with other genotypes only rarely being described.

The aim of this study was to evaluate viral load levels in serum samples of Brazilian patients diagnosed with chronic hepatitis B. Secondary objectives were to assess ALT levels and HBeAg status, stratified according to the different serum HBV-DNA levels.

MethodsStudy subjects and laboratory testsDiagnósticos da América (DASA) is a private medical diagnostics company with branches in all the major urban areas of Brazil with the exception of the northern region: in the south (in the state of Paraná), in the southeast (in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro), in the northeast (in the state of Ceará) and in the Midwest (in the state of Goiás and in Brasilia, the Federal District). DASA receives samples from patients with private health insurance (about 30% of the Brazilian population has access to private health insurance) and is not a service provider for the public healthcare system. In the present study, the DASA database was used to analyze the results of samples collected between July and December 2007 as part of the routine evaluation of CHB patients. Of the samples analyzed, measurements were performed on the same day in 510 cases, while the samples from the remaining 54 patients were analyzed within 1 month of HBV viral load sampling. When several samples were available for the same patient, the first available result was selected. This diagnostics company does not register any data regarding treatment. Eligibility criteria included age ≥ 18 years, hepatitis B (HBsAg positive) diagnosed more than six months previously, and availability of HBV-DNA samples. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Heliópolis Hospital, São Paulo, Brazil.

Demographic information obtained with respect to the patients included age, gender, city and region of origin, and ethnicity. Serological tests included ALT (alanine aminotransferase) and AST (aspartate aminotransferase) performed using enzyme immunoassay (Synemed, Benicia, US); HBsAg, HBeAg and HBeAb performed by chemiluminescence (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL); and viral DNA detected using real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and validated with a commercially approved RT-PCR - TaqMan® (Roche) with intra and inter-assay ranges within acceptable limits. With this technique, a fluorescent signal is detected each time a copy of DNA is synthesized. The absolute quantification of the sample is compared to a standard curve in each assay. The methodology sensitivity is 75 copies/mL and linearity is between 75 and 75,000,000 copies/mL. The equipment used was an Applied Biosystems Real time PCR: SDS 7000/7500/7500 fast (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). The College of American Pathologists (CAP) proficiency assay is performed every 4 months and the Clinical Laboratory Accreditation Program (Programa de Acreditação para Laboratórios Clínico - PALC) is completed every 3 months as DASA’s quality control standard. All tests were performed in local facilities with the exception of HBV-DNA, which was performed at a central laboratory.

A subset analysis was carried out in which the clinically significant15 level of HBV replication was defined as a viral load of 10,000 copies/mL (approximately 2,000 IU/mL), reflecting a consequently high risk of developing liver complications. In this group of patients, the relationship between different HBV-DNA levels and HBeAg status and ALT levels was analyzed.

Statistical analysisFindings were described as measures of central tendency and variability. Comparisons between means were performed using the t-test or MannWhitney test, according to the underlying distribution of the variables. The relationships between HBV-DNA level (DNA copies/mL), ALT (IU/L) level, gender and HBeAg were assessed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with rank transformation for HBV-DNA level as a continuous variable and the chi-square test for HBV-DNA as a categorical variable (categories defined as < 300 (undetectable); 3009,999; 10,000-99,999; 100,000-999,999; and ≥ 1 million). Both ALT (normal, defined according to gender as 10-40 IU/L for males and 7-35 IU/L for females versus abnormal, defined as any value outside the normal range) and HBeAg (negative versus positive) were categorized for analysis. Missing values for these variables were not considered in the analysis. In all cases, the level of statistical significance was set at 0.05 (two-tailed).

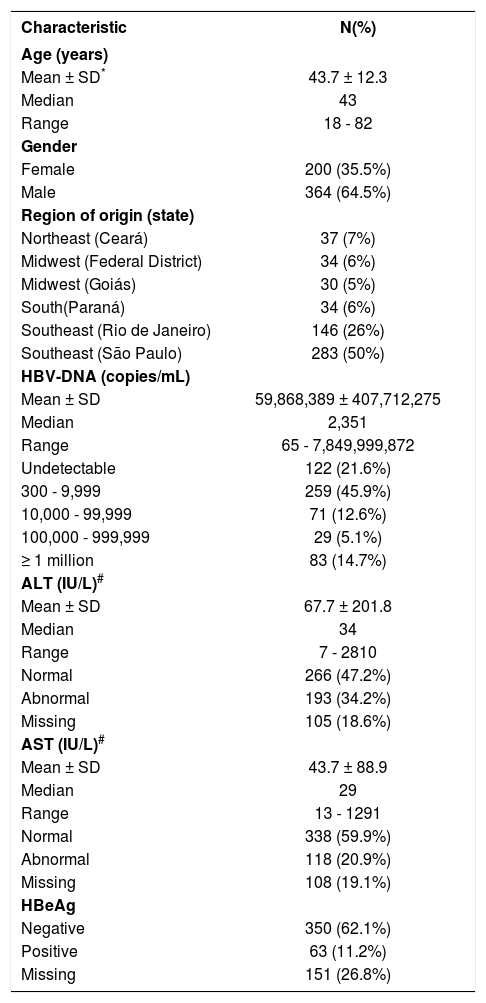

ResultsStudy populationA total of 2,050 consecutive patients who had tested positive for HBsAg were considered for this study. Of these, 27% (564) individuals were eligible for inclusion. The baseline characteristics and the distribution of serum HBV-DNA levels at admission to the study are shown in Table 1. In 122 study participants (21.6%), HBV-DNA levels were undetectable (< 300 copies/mL), while 112 participants (19.8%) had a level ≥ 100,000 copies/mL. No statistically significant correlation was found between HBV-DNA levels and the patient’s place of origin; however, females had lower HBV-DNA levels (median 1472.5) compared to males (median 2815), p < 0.0001.

Baseline characteristics of the 564 chronic hepatitis B patients comprising the study sample.

| Characteristic | N(%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| Mean ± SD* | 43.7 ± 12.3 |

| Median | 43 |

| Range | 18 - 82 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 200 (35.5%) |

| Male | 364 (64.5%) |

| Region of origin (state) | |

| Northeast (Ceará) | 37 (7%) |

| Midwest (Federal District) | 34 (6%) |

| Midwest (Goiás) | 30 (5%) |

| South(Paraná) | 34 (6%) |

| Southeast (Rio de Janeiro) | 146 (26%) |

| Southeast (São Paulo) | 283 (50%) |

| HBV-DNA (copies/mL) | |

| Mean ± SD | 59,868,389 ± 407,712,275 |

| Median | 2,351 |

| Range | 65 - 7,849,999,872 |

| Undetectable | 122 (21.6%) |

| 300 - 9,999 | 259 (45.9%) |

| 10,000 - 99,999 | 71 (12.6%) |

| 100,000 - 999,999 | 29 (5.1%) |

| ≥ 1 million | 83 (14.7%) |

| ALT (IU/L)# | |

| Mean ± SD | 67.7 ± 201.8 |

| Median | 34 |

| Range | 7 - 2810 |

| Normal | 266 (47.2%) |

| Abnormal | 193 (34.2%) |

| Missing | 105 (18.6%) |

| AST (IU/L)# | |

| Mean ± SD | 43.7 ± 88.9 |

| Median | 29 |

| Range | 13 - 1291 |

| Normal | 338 (59.9%) |

| Abnormal | 118 (20.9%) |

| Missing | 108 (19.1%) |

| HBeAg | |

| Negative | 350 (62.1%) |

| Positive | 63 (11.2%) |

| Missing | 151 (26.8%) |

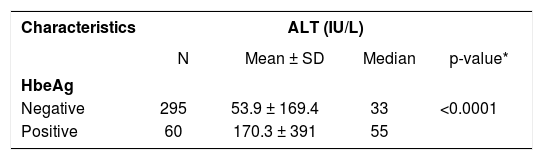

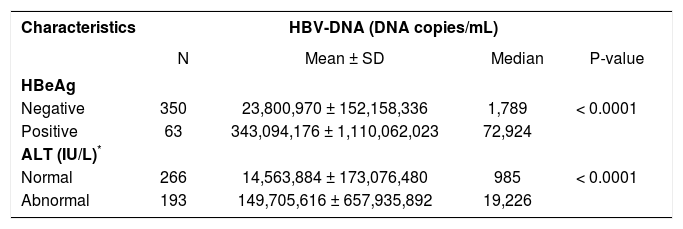

HBeAg-positive patients had significantly higher ALT levels (mean 170.3 ± 391 IU/L) compared to HBeAg-negative patients (mean 53.9 ± 169.4 IU/L), p < 0.0001 (Table 2). HBV-DNA levels were significantly higher in HBeAg-positive individuals and in those with elevated ALT levels compared to HBeAg-negative patients and those with normal ALT levels (p < 0.0001 for both comparisons) (Table 3).

HBV-DNA levels according to HBeAg status and ALT categories.

| Characteristics | HBV-DNA (DNA copies/mL) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean ± SD | Median | P-value | |

| HBeAg | ||||

| Negative | 350 | 23,800,970 ± 152,158,336 | 1,789 | < 0.0001 |

| Positive | 63 | 343,094,176 ± 1,110,062,023 | 72,924 | |

| ALT (IU/L)* | ||||

| Normal | 266 | 14,563,884 ± 173,076,480 | 985 | < 0.0001 |

| Abnormal | 193 | 149,705,616 ± 657,935,892 | 19,226 | |

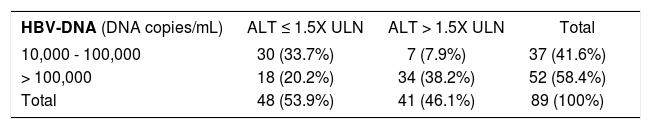

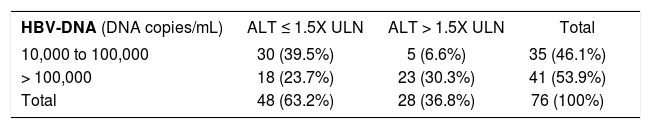

Subset analyses of individuals with clinically significant15 HBV-DNA levels (≥ 10,000 copies/mL), stratified according to whether or not ALT values were less than 1.5 times the ULN (upper limit of the normal range), are shown for the combined group of HBeAg-positive and HBeAg-negative patients together (Table 4) and for HBeAg-negative patients alone (Table 5). Analysis showed that 63.2% of HBeAg-negative patients with HBV-DNA levels > 10,000 copies/mL had ALT levels less than l.5 times the ULN (Table 5).

Relationship between HBV-DNA and ALT levels (the combined group of HBeAg-positive and negative patients together).

| HBV-DNA (DNA copies/mL) | ALT ≤ 1.5X ULN | ALT > 1.5X ULN | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10,000 - 100,000 | 30 (33.7%) | 7 (7.9%) | 37 (41.6%) |

| > 100,000 | 18 (20.2%) | 34 (38.2%) | 52 (58.4%) |

| Total | 48 (53.9%) | 41 (46.1%) | 89 (100%) |

P-value < 0.0001.

Relationship between HBV-DNA and ALT levels in HBeAg-negative patients.

| HBV-DNA (DNA copies/mL) | ALT ≤ 1.5X ULN | ALT > 1.5X ULN | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10,000 to 100,000 | 30 (39.5%) | 5 (6.6%) | 35 (46.1%) |

| > 100,000 | 18 (23.7%) | 23 (30.3%) | 41 (53.9%) |

| Total | 48 (63.2%) | 28 (36.8%) | 76 (100%) |

P-value = 0.0002. ALT: Alanine transaminase. HbeAg: Hepatitis B e antigen. HBV: Hepatitis B virus.

This study provides a cross-sectional view of CHB in selected regions of Brazil, a country in which approximately 2 million people are estimated to be HBV carriers.5 Although in some areas of Brazil, such as the western Amazon basin, prevalence rates are as high as 16%,16 endemicity in the country as a whole is considered intermediate, ranging from 1% to 8%.8,17

The primary objective of this study was to identify the distribution of viral load levels in Brazilian CHB patients living in six states which, together, contain almost half the country’s total population.18 HBV-DNA levels were undetectable in 21.6% of participants, while 58.5% had levels ranging from 300 to 99,999 copies/mL and 19.8% had levels ≥ 100,000 copies/mL. More importantly, the present study demonstrates that the viral load levels in Brazilian CHB patients are comparable to those described in studies conducted in Taiwan3,4 in which HBV-DNA levels were undetectable in 23.9% of study participants, while 26.7% had levels ≥ 100,000 copies/mL. Nevertheless, it is difficult to compare the present study with these other earlier studies due to the differences in HBV genotypes between Asia and Latin America. In agreement with current literature,3,4 in the present study viral load levels were lower in the population of HBeAg-negative patients compared to the HBeAg-positive patients, patients with abnormal ALT levels usually having a higher viral load level.

The present study also assessed the relationship between HBV-DNA levels and ALT levels and HBeAg status. In accordance with previous reports on ALT and HbeAg,19,20 this study has shown that HBV-DNA levels are significantly higher in HBeAg-positive individuals and in those with abnormal ALT levels. HBeAg was positive in 15.3% of individuals for whom these results were available, a proportion that is almost identical to that observed in the REVEAL-HBV study. In the latter study, individuals were seronegative for antibodies against the hepatitis C virus at study entry; on the other hand, no data regarding hepatitis C virus antibodies were available in the present study, which precludes evaluation of a possible role of a comorbid hepatitis C infection as a factor contributing to liver damage. Furthermore, it is conceivable that ALT levels in the Brazilian patients included in this study reflected the absence of antiviral treatment in many cases, since information on such treatment was unavailable.

Current hepatitis B treatment guidelines generally recommend no treatment for HBeAg-negative patients with normal or only slightly elevated ALT levels (i.e. ≤ twice the ULN), since they are not considered to have the active disease.21

However, when our subset analysis focused on such individuals, a relatively large proportion was found to have HBV-DNA levels > 10,000 copies/mL. This threshold was used since the effect of treatment in this population is unknown, making it impossible to distinguish those patients in whom low HBV-DNA levels are a result of therapy and seroconversion from those patients in whom the disease is inactive. By excluding those individuals with low viral load levels from this analysis, our objective was to assess the prevalence of a high viral load and to evaluate ALT, since it would be expected that most patients with high ALT levels would have the active disease.22,23

In Brazil, tests for the evaluation of HBV-DNA levels are not generally available within the public healthcare system; therefore, in HBeAg-negative patients with normal ALT levels the disease may be wrongly classified as inactive. Consequently, the clinical follow-up of these patients will not include liver biopsy or any form of treatment. This study identified a number of patients with this profile and it is probable that patients in similar conditions would be missed within the public healthcare system, in which HBV-DNA testing is not routinely performed. Furthermore, in the absence of serial HBV-DNA measurement, physicians caring for CHB HBeAg-negative patients may find it difficult to decide when to perform biopsy and/or initiate antiviral therapy. Furthermore, studies published in the literature24,26 report that patients with elevated HBV-DNA levels are more prone to disease progression. For example, Yuen, et al. showed that age, gender, core promoter mutation, HBV-DNA and cirrhosis, but not ALT levels, are predictive of the development of HCC. Nevertheless, Feld, et al. carried out a prospective study and showed that HBV-DNA levels > 10,000 copies/mL in HBeAg-negative patients with normal ALT levels was a relevant predictor of elevated ALT levels at future follow-up visits.22,27 Considering the evidence that viral load levels > 10,000 copies/mL are associated with an increasing probability of cirrhosis of the liver3 and HCC,4,18,24 we believe that there is growing evidence that patients with high HBV-DNA levels and low ALT levels should be considered to be harboring the active infection and to be at an increased risk of complications. These patients, therefore, demand to be followed-up more closely.

There are some potential limitations to the present study that should be taken into consideration, such as the uncertainty with respect to how representative the sample is of the population of interest, namely all individuals with CHB in the six states participating in this study and, more broadly, in Brazil as a whole. Although DASA is one of the largest medical diagnostics companies in the country, its presence covering an area that is both geographically large and densely populated, access to healthcare in Brazil is unevenly distributed through the various socioeconomic strata of the population. The patients using the facilities of this laboratory tend to be individuals of middle to high socioeconomic class who have access to private healthcare. It is, therefore, possible that health-related habits, body weight and access to treatment are different from those of patients in the Amazon region, the area in which HBV is most endemic. Nevertheless, some endemic areas are located in the southeastern and southern regions of the country and patients there may more closely resemble the patients enrolled in this present study. Another important limitation is the lack of information regarding any therapy administered to these patients. While some measures were taken to identify treatment-naive patients in the database and since analysis of the subset of patients with > 10,000 copies/mL was also aimed at excluding those patients with low viral loads probably indicative of ongoing treatment, it is impossible, however, to guarantee the treatment status of patients and to be certain whether viral load levels are a consequence of the disease or the treatment.

Despite the potential limitations outlined above, the database used in this study offered an unique opportunity to evaluate several aspects of chronic hepatitis B in Brazil. Furthermore, correlating this data with various papers published in the literature on the evaluation of HBV-DNA levels and disease progression3,4,24-26 may provide at least a rough estimate regarding the risk of progression to HCC in this Brazilian sample of chronic HBV patients, provided other differences such as age, ethnicity, genotype and the lack of data regarding antiviral treatment, among other issues, are taken into account. The advent of new, effective therapies for HBV has provided the physician treating these patients with a greater possibility of controlling the disease in many HBV-infected patients. The findings of the present study may contribute towards further studies designed to reach a better definition of the population at risk and may help increase awareness with respect to the prevalence of the principal factors that seem to affect the risk of disease progression in the Brazilian population.

AcknowledgementThe authors would like to express their gratitude to the investigators and reviewers, including Drs. UH Iloeje, DL Butcher and BC Donato, among others, who collaborated in the preparation of this manuscript and in conducting the study.

Abbreviations- •

HBV: Hepatitis B Virus

- •

HBeAg: Hepatitis B e Antigen

- •

ALT: Alanine aminotransferase

- •

CHB: Chronic hepatitis B

- •

HCC: Hepatocellular carcinoma

- •

DASA: Diagnósticos da América

- •

AST: Aspartate aminotransferase

- •

RT-PCR: Real-time polymerase chain reaction

- •

ULN: Upper limit of the normal range

This study was supported by a research grant from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Co.

Marcelo Eidi Nita, Gilbert L’ltalien, Patricia Mantilla and Nancy Cure-Bolt are all employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Nelson Gaburo Jr. is an employee of DASA.

Hugo Cheinquer, Evaldo Stanislau Affonso de Araujo and Paulo Andrade Lotufo have all participated in clinical research studies and all received honoraria for their participation as investigators in this study.