Introduction and Objectives: Elevated liver enzymes (ELE) are a common finding in the general population, often caused by undiagnosed chronic liver disease. But little is known to what extent socioeconomic status (SES) influences the occurrence of various liver diseases.

Material and Methods: Retrospective study of outpatients presenting with ELE. All patients received a structured work-up including abdominal ultrasound and serological testing. SES was assessed for patients from the Hamburg area using the social monitoring database of the Hamburg City Housing Department. SES was rated as high (SES-H), medium (SES-M), and low (SES-L).

Results: Out of n=859 patients analysed, SES was assessable for n = 310 (53%) patients: SES-H/-M/-L [n; %]: 31 (10%), 223 (72%), 56 (18%). The most prevalent liver diseases were NAFLD (n=125; 40.3%), drug-induced liver injury (n=16; 5.2%) and alcoholic liver disease (ALD, n=13; 4.2%). Prevalence of NAFLD differed significantly between SES-subgroups (SES-H/-M/-L [n; %]: 6 (19%) vs. 88 (39%) vs. 32 (55%); p= .004), the distribution of ALD was similar between the SES subgroups (1(3.2%) vs. 11 (4.9%) vs. 1 (2%); p= .55). Median body mass index (BMI) increased from SES-H to SES-VL (SES-H/-M/-L [kg/m2]: 24.4 vs. 26.2 vs. 28.6; p= .001).

Conclusions: NAFLD is the most prevalent liver disease in patients presenting with unexplained ELE, with a significantly higher occurrence in individuals from lower SES groups. Furthermore, BMI increases among patients with lower SES, highlighting the potential role of socioeconomic factors in NAFLD development. These findings underscore the need for targeted public health interventions, particularly in socioeconomically disadvantaged population.

Elevation of liver enzymes, e.g. alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gamma-glutamyltransferase (γGT), is a frequent finding in the German population: Baumeister et al. report a prevalence of elevated ALT of 15.8% in a cohort of 4310 patients in Pomerania [1]. Furthermore, in a recent study by Huber et al., including 14.950 patients in the Rhine-Main Region, almost 20% of patients were found to have elevated liver enzymes, and the prevalence of advanced liver fibrosis was estimated to be 1% in the German population [2].

Elevated liver enzymes are primarily caused by chronic liver diseases such as hepatitis B (HBV) and hepatitis C (HCV) infections, as well as alcoholic liver disease (ALD) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which can subsequently lead to the development of liver fibrosis or cirrhosis. While chronic HBV or HCV infection accounts for almost two-thirds of the global burden of liver cirrhosis, the prevalence of NAFLD is constantly rising, particularly in industrialized nations, and is estimated to be 25% worldwide with distinct regional variations [3,4]. In Europe, the prevalence of NAFLD varies between 23.9% in the United Kingdom and 48% in the Palermo region in Italy [5,6].

Regarding the fact that NAFLD can progress to inflammatory steatohepatitis (NASH) and subsequently to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis, NAFLD/NASH is expected to become the dominant cause of liver cirrhosis within the next years [7,8]. Of note, NASH has already become the second leading liver disease of patients waiting for liver transplantation in the United States [9]. Several risk factors for the development of NAFLD have been described so far: obesity, insulin resistance, or type 2 diabetes as well as elevated levels of blood lipids have been identified [10,11]. Furthermore, the patient´s socioeconomic background also seems to influence the prevalence of NAFLD, but recent studies reveal inconsistent findings: While Hu et al. report that the prevalence of NAFLD is positively correlated with higher income and economic status, in two cohort studies from Japan and Korea a higher body mass index (BMI) was associated with a lower economic background in adolescents and adults [12–14].

Alcoholic liver disease (ALD), a clinical spectrum that comprises fatty liver disease, alcoholic steatohepatitis, and, liver cirrhosis, has been the most prevalent cause of chronic liver disease in Europe for many years. Alcohol-related and alcohol-attributable deaths have been found more often in unprivileged groups, while on the other hand, alcohol consumption is positively correlated with the economic standing of a country [15–17]. But despite the significant health and economic impact of these disease entities, the impact of the economic status of both diseases remains unclear.

In general, the socioeconomic status (SES), reflects the ability of a person to assess distinct resources, such as material goods, healthcare, or educational opportunities, and is an important measure in health sciences [18]. The calculation of SES provides an assessment of social stratification and inequalities in a society, and can also reflect changes of social status over time, when calculated repetitive [19]. Several methods to measure SES have been described: SES can be calculated either on an individual level or at the level of an individual’s residential environment or neighbourhood, based on distinct variables such as the proportion of residents who were dependent on social benefits, residents per general practitioner or share of the population with an academic degree, etc. [20,21]. Using an environment-based method, many studies have demonstrated a relationship between a poor SES, harmful health behaviour, and the outcome of chronic diseases such as coronary heart disease or cancer [22–25]. Furthermore, in patients with liver cirrhosis, Dalmau-Bueno et al. report the highest death rates among patients with the lowest educational level and in socioeconomically deprived areas in Barcelona, Spain, underlining the impact of socioeconomic inequalities in patients with chronic liver disease [26].

The social monitoring database of the Hamburg City Housing Department provides a zip-code-based calculation of the SES for residents of the City of Hamburg, Germany, based on seven socio-economic parameters. The monitoring database was initially established in 2010 for early identification of underprivileged areas and to guide supportive measures or restructuration programs in the city of Hamburg [27]. Since 2010, the database has been updated annually and is publicly accessible without restrictions.

In January 2019, as a consequence of the tremendous number of patients presenting with liver enzyme elevation of unknown cause, a structured diagnostic algorithm was established at the hepatology outpatient clinic of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, to enable a timely diagnosis and to identify patients requiring medical treatment. The aim of this study was a) to assess the incidence of primary liver diseases in patients presenting with elevated liver enzymes at a referral center and b) to analyze the association between the patient’s SES and the prevalence of alcoholic as well as non-alcoholic liver disease.

2Patients and Methods2.1PatientsAll patients with elevated liver enzymes of unknown origin presenting to the hepatology outpatient clinic of the First Department of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE) from January 1th to December 31th 2019 were included in this analysis. Hamburg is a large city with 1.8 million inhabitants. The UKE is the largest hospital in this region and, with its outpatient clinic for hepatology, provides a point of contact for patients from Northern Germany. Patients presenting with previously unexplained elevated liver enzymes received a structured laboratory work-up including whole blood count (hemoglobin, mean hemoglobin concentration, mean corpuscular volume, platelets, and white cell count), blood chemistry including AST, ALT, γGT, alkaline phosphatases, glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH), albumin, total protein concentration, bilirubin, creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), sodium, potassium, c-reactive protein (CRP), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatinine kinase (CK), blood sedimentation rate (BSG) and coagulation test (international normalized ratio (INR), quick value). To test for autoimmune liver disease, anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibodies (ASM), liver-kidney-microsomal antibodies (anti-LKM), anti-filamentous actin (f-actin) antibodies as well as anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA) had been measured. Testing for hepatitis A, hepatitis E, HBV, HCV infection, screening for hemochromatosis (ferritin, transferrin, and total transferrin saturation), Wilson´s disease (coeruloplasmin), celiac disease (anti-transglutaminase antibodies) and alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency, a blood lipid profile as well as glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) had been obtained.

Additionally, an ultrasound scan of the abdomen to screen for liver masses, evidence of parenchymal damage, and echogenicity of the liver as well as a measurement of liver stiffness via fibroscan ® including assessment of the controlled attenuation parameter (CAP) was carried out in every patient by an experienced clinician. For screening of alcohol misuse, urinary ethyl glucuronide and carbohydrate-deficient transferrin (CDT) in the serum were obtained. Patients were questioned for complete medical history on first presentation, drinking habits, co-medication, intake of supplements and over-the-counter drugs (OTC), family history of liver diseases, and profession. Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) was calculated in every patient to assess comorbid conditions. Body height and current weight was assessed on initial presentation. All data were retrospectively collected by reviewing the electronic patient record system and were analyzed post hoc.

2.2Liver biopsyIn patients with inconclusive diagnosis, liver biopsy was conducted for further workup. Biopsy was obtained upon individual decision as there was no strict standardized operation procedure. Liver biopsy was performed using a mini-laparoscopic technique as previously described or ultrasound guided [28]. In selected patients, Menghini puncture was carried out because of contraindications for laparoscopic technique. All specimens were analysed in the Department of Pathology of the University Medical Center Hamburg- Eppendorf using well established methods for histopathological staining.

2.3Diagnosis of NAFLD and ALDIn patients with elevated liver enzymes and sonographic findings of liver hyperechogenicity and/or elevated CAP- values > 300 dB/m without evidence of any other underlying liver disease and no history of regular alcohol intake or abuse, NAFLD was diagnosed, after exclusion of other underlying liver diseases as Wilson´s disease, hemochromatosis, autoimmune hepatitis, viral hepatitis od alpha 1 antitrypsin deficiency. ALD was diagnosed similarly in patients reporting regular alcohol consumption (e.g. more than one standard drink per day in females and > two standard drinks daily in male patients) or alcohol abuse and/or who had positive urine-ETG findings on first presentation and no evidence of any underlying liver disease.

2.4SES assessmentSES was obtained by using the social monitoring database 2019 of the Hamburg City housing department. The calculation of SES is based on seven defined indices obtained for a statistical area, which is defined by at least 300 residents of the city of Hamburg. In 2019, a total of 852 areas had been evaluated. Indices analyzed for each statistical area include: (i) proportion of children and adolescents with migration background, (ii) rate of children with single parents, (iii) proportion of people receiving basic security benefits for job seekers or seeking asylum (iv) unemployment rate (v) proportion of children below 15 years of age receiving basic security benefits (vi) rate of residents receiving old age security and (vii) proportion of younger people without any graduation. Based on these seven indices, SES is rated as high (SES-H), medium (SES-M), low (SES-L), and very low (SES-VL). To improve comparison and enable statistical calculation, the subgroups SES-L and SES-VL were summarized as SES-L in this study For each patient in this study, SES was assessed using the zip-code-based database ‘Sozialmonitoring Karten- und Tabellenband 2019’ provided by the Department of Urban Development and Housing, City of Hamburg (assessable: https://www.hamburg.de/contentblob).

2.5Statistical analysisData are expressed as frequencies (%) for categorical variables and as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables. Fisher’s exact test was used for categorical variables and the paired Student’s t-test for continuous variables or paired non-parametric test when assumptions of normality could not be verified. Multivariate logistic regression was calculated for selected variables, that had been tested for significant correlation in univariate testing. Microsoft ® Excel was used for the baseline database, and SPSS Version 26 and GraphPad Prism ® Version 8.3 were used for calculation.

2.6Ethics statementData were anonymized and analysis could thus be conducted in accordance with local government law (HmbKHG. §12) and based on the informed consent provided in the general hospital contract, signed at the initial presentation to the outpatient clinic.

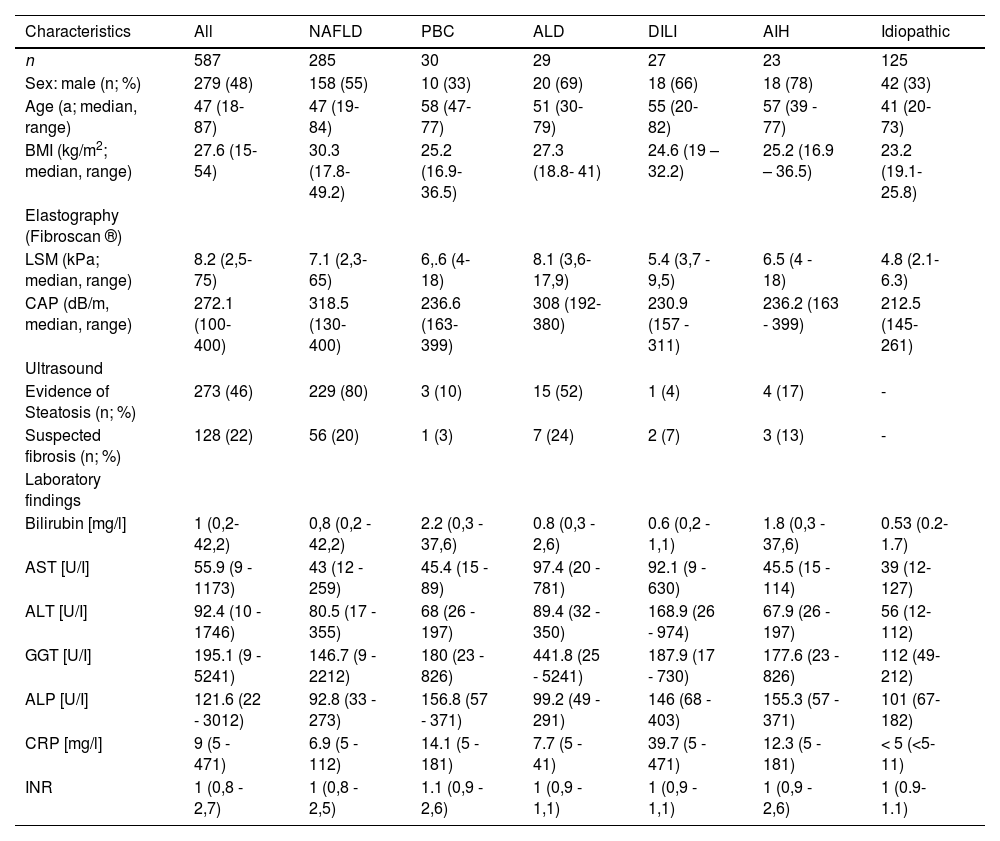

3ResultsOut of n=859 patients, who had been treated at the hepatology outpatient clinic between January 1st and December 31st, 2019, n= 587 (67%) presented due to unclear elevated liver enzymes, the median age was 46.5 years (range: 18- 87 years), 51.7% were female. Median values (range) in the entire cohort were AST: 50.4 U/I (13- 630; upper limit of normal [ULN]: 50 U/I for male and 35 U/I for female patients), ALT: 61 U/I (12- 974; ULN: 50 U/I for male and 35 U/I for female patients), γGT: 95 U/I (11- 5241; ULN: 60 U/I for male and 40 U/I for female patients), and bilirubin: 1.0 mg/dl (0.2- 37.6; ULN: 1.1 mg/dl). Characteristics and laboratory findings of the study cohort are depicted in Table 1.

Demographic characteristics, diagnostic and laboratory findings in patients with different liver diseases.

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALD, alcoholic liver disease, ALP, alkaline phosphatase, ALT, alanine transaminase; AST, aspartate transferase; BMI, Body Mass Index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; CRP, C-reactive protein; DILI, drug induced liver injury; GGT, gamma-glutamyltransferase; INR, International Normalized Ratio; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

After non-invasive testing, the following underlying liver disease were diagnosed: NAFLD (n= 260; 44.3%), primary biliary cholangitis (PBC; n=28; 4.7%), ALD (n=27; 4.5%), drug-induced liver injury (DILI; n=27; 4.5%), HCV- (n=3; 0.5%) and HBV-infection (n=2; 0.3%). In n=45 patients’ various other diagnoses were found: primary or secondary sclerosing cholangitis, haeochromatosis, gallstones, cholangio- or gall bladder carcinoma, hepatitis E infection, parainfectious hepatitis and hepatic congestion due to decreased cardiac output.

In the remaining n=195 patients, no final diagnosis was established following non-invasive testing. For further diagnostic work up, a liver biopsy was carried out in n=82 patients. Suspected autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) was confirmed in n= 23 patients. In n=47 patients the following diagnoses were established based on histological findings: NAFLD/NASH (n=25), ALD (n=2), PBC (n=2), PSC (n= 14), suspected vascular disease (n=3) and haemochromatosis (n=1). Histological findings were unremarkable in the remaining n= 12 patients.

Taken together, the results from non-invasive and invasive procedures show that the most prevalent underlying liver diseases were NAFLD (n = 285; 48.5%), PBC (n = 30; 5.1%), ALD (n = 29; 5%), DILI (n = 27; 4.5%), and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH; n = 23; 3.9%).

A total of n = 125 patients (21.3%), including n = 12 with liver biopsy and n = 113 with only non-invasive diagnostics, received no diagnosis (idiopathic elevated liver enzymes). Patient characteristics and laboratory findings are depicted in Table 1.

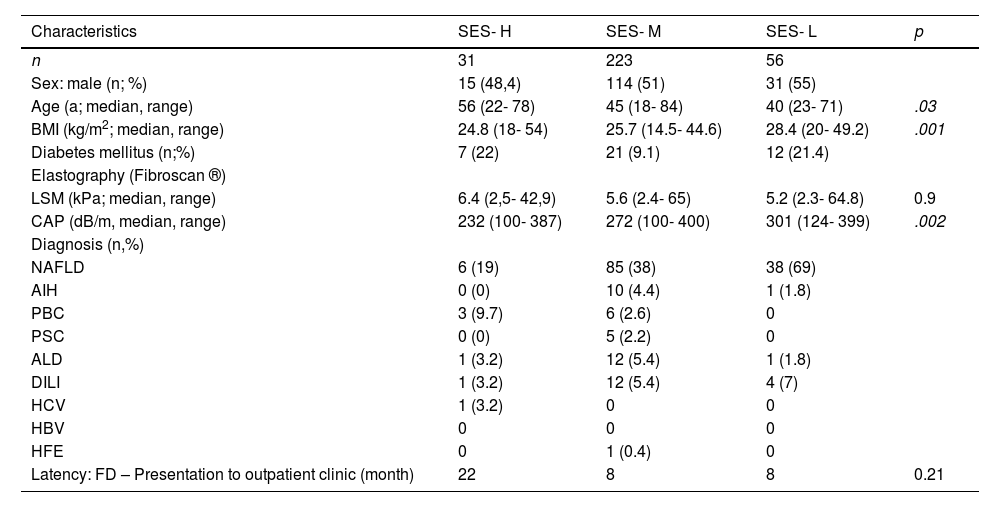

Among patients of the study cohort, a total of n= 310 (53%) patients were residents of the city of Hamburg for whom SES was available (SES-cohort). According to the social monitoring database, SES was rated as high (SES-H) in n=31 (10%) patients, medium (SES-M) in n=223 (72%), low (SES-L; including patients with low and very low SES) in n=56 (18%) patients (Fig. 1). The most prevalent liver diseases of Hamburg residents were NAFLD (n=125; 40.3%), drug-induced liver injury (n=16; 5.2%), ALD (n=13; 4.2%), and autoimmune hepatitis (n=12; 3.9%). Distribution of patients diagnosed with NAFLD differed significantly between distinct SES classes: NAFLD was found significantly more often in SES-L than in SES-H and SES-M patients (19% vs. 39% vs. 55%; p= .004). For patients diagnosed with ALD, AIH, PBC, DILI, or chronic viral Hepatitis, distribution differed non significantly between SES classes. Regarding the risk factor for NAFLD, patients in the SES-L subgroup were found to have a significantly higher body-mass index (BMI; kg/m2) compared to the SES-H and SES-M cohort, and the median BMI was constantly increasing towards lower SES classes: 24.1 kg/m2 vs. 26.1 kg/m2 vs. 28.6 kg/m2 (Fig. 2).

Flowchart of the study. A total of n=859 patients presented to the hepatology outpatient clinic between 1th January to 31th December 2019, n= 587 were transferred due to previously unexplained elevated liver enzymes. In both, Hamburg resident and extra-urban patients, NAFLD was the most prevalent underlying liver disease. Social economic status was assessed for Hamburg resident patients.

Abbreviations: AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALD, alcoholic liver disease; DILI, drug-induced liver injury; ELE, elevated liver enzymes; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; SES, socioeconomic status; SES-H, high SES; SES-M, medium SES; SES-L, low SES; SES-VL, very low SES.

Among all patients presenting with elevated liver enzymes of unknown cause, patients in the SES-L cohort were significantly younger compared to the SES-H subgroup. In a multivariate logistic regression analysis including age, gender, BMI, SES, presence of diabetes and CCI as independent variables, only the presence of diabetes (odds ratio [OR]: 3.14; 95% CI: 1.38- 7.35, p= .0067) and SES (OR: 1.43; 95% CI: 1.05- 1.94; p= .024) was significantly associated with diagnosis of NASH/NAFLD. The latency between a general practitioner's first assessment of elevated liver enzymes until presentation to the university hepatology clinic was comparable between SES classes. Characteristics of the SES cohort are depicted in Table 2.

Demographic characteristics and diagnoses in patients with unexplained hepatopathy according to the socioeconomic status (SES).

AIH, autoimmune hepatitis; ALD, alcoholic liver disease; BMI, Body Mass Index; CAP, controlled attenuation parameter; DILI, drug induced liver injury; FD, first diagnosis of liver enzyme elevation of unknown cause; HBV, HCV, viral hepatitis B/C; HFE, hemochromatosis; LSM, liver stiffness measurement; PBC, primary biliary cholangitis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; NAFLD, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Unexplained elevated liver enzymes are a frequent finding in the general population and a common cause for patients to consult hepatologists. In our study, 65% of the patients had been transferred to the University Medical Center due to elevated liver enzymes of unknown aetiology. Out of the patients who were Hamburg residents, the majority of patients had a high- or medium SES, while only 18% were classified as having low SES. The distribution of different SES levels in our cohort is comparable to the SES ranking for the city of Hamburg in 2019 (SES-H: 17%; SES-M: 65%, SES-L: 17%), indicating a representative study cohort.

According to the structured diagnostic work-up that has been applied to every patient, NAFLD is by far the most prevalent underlying liver disease in Northern Germany. This finding is in line with a recent study by Younossi et al reporting that NAFLD is the most prevalent chronic liver disease in Germany with approximately 12 million being affected and more than 750,000 patients suffering from NASH [4]. Furthermore, in a retrospective study by Clark et al. comprising more than 15,000 individuals in the United States who had been screened for elevated liver enzymes, an explanation and final diagnosis for aminotransferase elevation was only found in 31% of all patients. However as unexplained enzyme elevation was strongly associated with obesity and metabolic syndrome, the authors assume that NAFLD is most likely the leading underlying liver disease in these patients [29].

It should be noted that in our study, no cause of the abnormal liver function test was found in nearly 22% of patients, despite a comprehensive non-invasive diagnostic approach. Most of these patients had only mildly elevated aminotransferases or gamma-GT, with no evidence of fatty liver disease or any other condition tested. As no follow-up presentations were recorded in the electronic files, it can only be speculated whether the liver enzymes were temporarily elevated or if the laboratory findings reflected the early onset of a disease, which was presumably diagnosed later. Since many of these patients had only mild or very slight elevations in transaminases, in many cases, a liver biopsy was not performed, and follow-up monitoring with the general practitioner was recommended, with the advice to return if values increased again.

Although elevated liver enzymes are a frequent and sometimes incidental finding in the general care setting, the diagnosis of the underlying disease remains a challenge: in study of 308 patients with abnormal liver function test, a final diagnosis was made in n= 224 (73%) [30]. These findings are in line with the results of our study. In the prospective British BALLETS trial, only 5% of included patients with abnormal liver function test had a specific liver disease in the end [31]. This study also identifies ALT and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) as the most potential analytes to identify patients with severe underlying liver disease. This finding is contrast to our study, were a majority of patients elevation of predominantly gamma-GT.

While most prospective study, like BALLETS trial, used a structured questionnaire to assess alcohol consumption, diagnosis of alcohol abuse was based on a non-structured assessment by the respective doctor. In addition, we used urinary ethyl glucuronide and serum CDT to screen for alcoholic liver disease. Given the fact, that both, the urinary test and CDT only reflect the alcohol abuse within the last few days and in the lack of standardized alcohol screening tool, we cannot rule out, the prevalence of alcoholic liver disease is underscored in our study.

As most of our study's patients have been referred to the hepatology clinic by general practitioners, where patients had initially been seen due to elevated liver enzymes. As the diagnosis of NAFLD has not been established in this first presentation, this points towards an underestimation or a missing awareness of NAFLD in this setting. In fact, Patel et al. report that the spectrum of NAFLD has been underestimated by primary care clinicians in the Brisbane area when questioned about symptoms and prevalence of the disease [32]. Therefore, an information campaign addressing primary care clinicians and optimized easily to handle diagnostic tools is needed to facilitate timely diagnostic and subsequently therapeutic interventions in the primary care setting.

The development of NAFLD in a given patient is based on several clinical, environmental, and genetic risk factors such as PNPLA3 or TM6SF2 gen variants, male gender, obesity, insulin resistance, or diabetes, for example, but the impact of the socioeconomic status of the disease onset appears to be different in various counties: while Mar et al identified low socioeconomic status as a risk factor NALFD development in the United States, Hu et al described an association between higher income and NAFLD in a Chinese cohort [12,33–37]. In our study, NAFLD was more prevalent in patients with a lower SES. Furthermore, regarding risk factors for disease development, we found that the BMI was constantly increasing from patients with high SES to those with lower SES. Several studies have investigated the relationship between low areal SES and obesity. Mohammed et all reported a 31% higher odds of overweight in areas with lower neighbourhood SES [38]. Furthermore, is has been described by El-Sayed et al. that there is a significant annual increase in obesity and BMI in low level SES areas [39]. The reasons for the increasing incidence obesity in low SES area are multiple: the consumption of unhealthy food, e.g. less nutritious, energy-dense foods are often cheaper than a healthy, balance died and food expenditure is lower among low socioeconomic groups [40–42]. In addition, unhealthy foods have been found to be more often advertised by supermarkets in a Dutch study [43]. Next, the built environment in SES areas seems to play a role, as physical activity and healthy eating behaviour is easier in places where people have the opportunities to buy healthy food have access to urban green spaces and a higher walkability [44–46]. Regarding the various risk factors of obesity in lower SES areas, the results of our study further underline the urgent need for specific interventions, such as nutritional advice or sports programs, due to the large proportion of patients with NAFLD in this cohort and the increasing BMI in lower SES groups. It appears reasonable that such therapeutic interventions should focus on patients in underprivileged areas or on people with low SES, respectively, as these patients seemed to be more prone to the development of fatty liver disease. Another concerning fact is, that patients in the SES-L subgroup who had primarily been diagnosed with NAFLD were significantly younger than patients with higher SES levels, indicating that these patients had been these patients were exposed early in life to relevant risk factors such as high-calorie diet and lack of exercise.

Although it has been described in previous studies that alcoholic liver disease is associated with lower socioeconomic status, we found no correlation between SES and the prevalence of ALD in our cohort [15,47,48]. The calculation of SES in this study was based on the database of the Department of Urban Development and Housing of the City of Hamburg, using the above-mentioned variables and providing an assessment of the socio-economic environment of small, defined urban areas. The methodical rationale for SES calculation was initially described by Otis Ducan in 1955 and has been widely used since then [49]. Although different methods are established to determine the SES, there is no gold standard to our knowledge. In several studies where SES was calculated on variables such as unemployment rate, education level of residents, etc., similar to those variables used for the Hamburg SES database reflecting the socioeconomic environment of a resident, an association between SES and prevalence of chronic disease has been demonstrated [22,50–52]. Therefore, we decided to use the Hamburg Sozial monitoring database, as the SES calculation is based on an established method.

Our study has several limitations that need to be addressed: first, the diagnosis of NAFLD was mainly based on non-invasive diagnostic tests such as ultrasound findings or measurement of the CAP-value, and inter-observer variability cannot be ruled out. Additionally, NAFLD was diagnosed in patients who presented with specific findings on ultrasound and denied significant alcohol consumption. However, the diagnosis has not been confirmed by liver biopsy, and in some cases, additional alcohol intake or coexisting alcoholic liver disease cannot be ruled out. Second, it has to be mentioned that all patients included in this analysis had been transferred to our reference center by general practitioners for further work-up. Assuming that a chronic hepatitis B or C virus infection had been ruled on first presentation to the general practitioner, it is most likely that the proportion of patients with chronic viral hepatitis is underrated in this cohort. Furthermore, only patients with compulsory insurance were included in this study, as the standardized workup procedure that has been carried out in every patient was established only in the hepatology outpatient clinic but not in our private outpatient clinic. Therefore, assuming a high SES for patients with private insurance, this subgroup of patients might be underrepresented in our study.

Finally, the SES subgroups in this study are of different sizes, hampering statistical calculations and potentially causing a bias.

5ConclusionsIn conclusion, this study demonstrates that NAFLD is the most frequent liver disease in patients with unexplained hepatopathy underlying both, the rising prevalence of the disease and probably a missing awareness for this chronic hepatitis in the field of a general practitioner. Due to the large number of newly diagnosed NAFLD patients referred to the tertiary referral center, broader awareness of the disease should be created through educational and information campaigns. Of note, NAFLD was significantly more often diagnosed in patients with lower SES, and the BMI, reflecting obesity as the most prominent risk factor for NAFLD, is constantly increasing with decreasing SES. Therefore, awareness campaigns as well as prophylactic and therapeutic interventions should focus on patients with lower SES to timely prevent disease progression.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors

None.

We like to thank the entire medical stuff of the outpatient clinic of the I. Department of Medicine, University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf and the nurses in the Department of ultrasound diagnostic for their support.