Hepatitis E virus is one of the most common causes of acute hepatitis worldwide, with the majority of cases occurring in Asia. In recent years, however, an increasing number of acute and chronic hepatitis E virus infections have been reported in industrialized countries. The importance of this infection resides in the associated morbidity and mortality. In acute cases, a high mortality rate has been reported in patients with previously undiagnosed alcoholic liver disease. Hepatitis E infection can become chronic in immuno-compromised patients, such as solid organ transplant recipients, patients receiving chemotherapy, and HIV-infected patients, and lead to the development of hepatic fibrosis and cirrhosis. Hence, treatment strategies involving reductions in immunosuppressive regimens and therapy with ribavirin or peg-interferon have been evaluated. In terms of prevention, a promising new vaccine was recently licensed in China, although its efficacy is uncertain and potential adverse effects in risk groups such as chronic liver disease patients and pregnant women require investigation. In conclusion, physicians should be aware of hepatitis E as a cause of both acute and chronic hepatitis in immunocompromised patients. The best treatment option for HEV infection remains to be defined, but both ribavirin and peg-interferon may have a role in therapy for this condition.

Hepatitis E virus (HEV) is a common cause of acute hepatitis infection worldwide.1 In developed countries, however, HEV is responsible for a small number of cases, being hepatitis A virus the most prevalent etiology.2–3 HEV infection was first described in 1980 through analysis of blood samples from patients affected by an acute hepatitis epidemic in New Delhi (India) during 1955 and 1956, spread by contaminated water.4 The causal agent in this epidemic, the “enteric non-A hepatitis virus” was identified in 19835 and named E, because of its enteric and endemic characteristics.

Although most HEV hepatitis cases occurring in industrialized countries are imported from areas where this infection is endemic, an increasing number of native cases have been reported. HEV infection in developed countries is generally caused by genotype 3 or 4, and is mainly diagnosed by serolo-gical testing in patients older than 60 years with unexplainable acute hepatitis.6 In the last few years, HEV has also been identified as a cause of chronic liver disease in immunocompromised patients, such as solid organ transplant recipients,7.–23 individuals infected by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV),24.–34 and patients with hematologic disorders receiving chemotherapy.35.–37 In addition, it has been found to cause acute decompensation in patients with chronic liver disease.38.–40

HEV is a non-enveloped virus 27 to 34 nm in size, with a 7.2-kb positive-sense single-stranded RNA genome. It contains 3 open reading frames (ORFs) as well as 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions: ORF1 encodes non-structural proteins, ORF2 encodes the capsid protein, and ORF3 encodes a small phosphoprotein.41–42 HEV is the unique member of the Hepe-virus genus and Hepeviridae family.2 Its resistance to inactivation by the acid and slightly alkaline conditions of the intestinal tract explains why its transmission mainly occurs via the fecal-oral route.

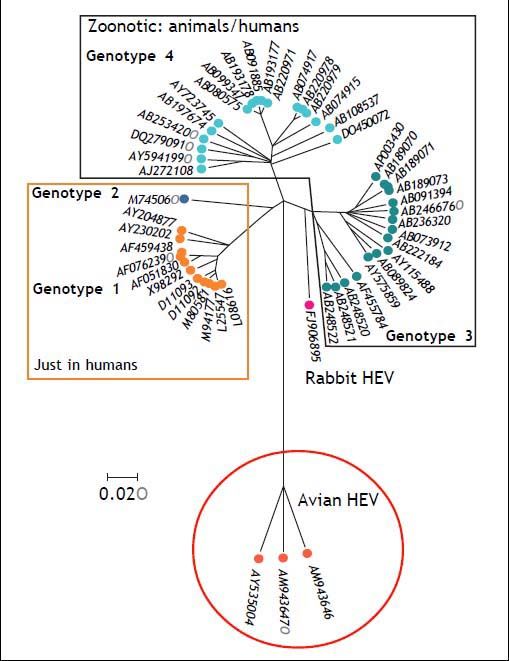

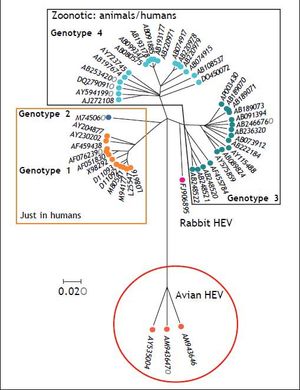

HEV comprises five genotypes, all belonging to one serotype.43 Genotypes 1 and 2 are strictly human and are associated with large outbreaks transmitted by contaminated water in countries where HEV infection is endemic, such as Asia for genotype 1 and Africa and Mexico for genotype 2.44 Genotype 3 and 4 can infect humans, but also other mammals, mainly pigs and deer. Genotype 5 is of avian origin and has only been described in birds. Figure 1 shows the phylogenetic tree of rabbit HEV.

Epidemiology Change in Developed CountriesThe first cases of HEV infection in industrialized countries were imported from developing areas in Asia and Africa. Since 1997, when the similarity between swine and human HEV strains was first des-cribed,45 an increasing number of native HEV infections have been reported in the USA, Europe, and developed Asian-Pacific countries (Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Australia). Although most of these cases have involved genotype 3 strains, some genotype 4 infections have been recently reported in France.46–47

In contrast to tropical countries, where HEV infection is fecal-orally transmitted by contaminated water, in industrialized countries, zoonotic HEV transmission is considered the main source of infection. There are also reported cases of transmission by blood transfusion48.–51 and liver transplantation.52 HEV3 and HEV4 infections have been related to ingestion of raw or undercooked meats, such as pig liver sausages or game meats,46,53,54 but the complete spectrum of animals that are HEV reservoirs is unknown. In the last years, several studies have characterized new HEV genotypes in rabbits in France,55 rats in Germany56,57 and the United Sta-tes,58 farm rabbits in China,59,60 and wild boars in Japan.61,62

A study performed in Spain revealed a higher prevalence of anti-HEV antibodies in swine industry workers in comparison to the general population (18.8 vs. 4.1%, p = 0.03).63 These data suggest that swine HEV infection promotes a high prevalence of HEV antibodies in individuals directly and frequently exposed to these animals, and exemplifies the zoonotic feature of this infection. HEV is endemic in swine and there is a high anti-HEV prevalence worldwide (almost 100% in the USA and Mexico, 90% in New Zealand, 46% in Laos, and 98% in Spain); furthermore, it shares genotypes 3 and 4, which are responsible for human infections in non-endemic areas.5

A study performed in Barcelona (Spain) showed that detection of HEV-RNA in urban sewage samples has remained stable (around 30%) despite overall improvements in sanitation. However, during the same 5– to 10–year period, the presence of hepatitis A virus dramatically decreased (from 57.4 to 3.1%). This observation highlights the importance of animal reservoirs of HEV, which act as external sources of infection.64 Studies on the presence of HEV in the pork food chain, revealed a 10 and 6% HEV detection rate in pork sausage at point of sale in the United Kingdom65 and Spain,66 respectively, and a rate in meat samples of 3% in the Czech Republic and 6% in Italy.66 The elevated detection of HEV in 60% of floor and working surfaces and 57 to 71% of hands and aprons of workers dissecting pigs, emphasizes the high risk for workers and highlights the need to improve preventive measures in these industries to avoid HEV transmission.66

Hepatitis E Diagnosis: Clinical Presentation and Extrahepatic ManifestationsIn endemic countries, HEV infection by genotypes 1 and 2 mainly affects children and young adults.4 The infection is more common in men, and the associated mortality rate in these areas is 1 to 15%. During outbreaks of this infection, pregnant women are particularly susceptible and show high mortality and morbidity rates (19 vs. 2.1% in non-pregnant women and 2.8% in men).67 HEV epidemics are also related to a high risk of prematurity and perinatal mortality.68

In contrast, in developed countries, HEV represents a minority of acute hepatitis cases, which are mainly attributed to genotypes 3 and 4. HEV infection in these countries essentially affects persons older than 60 years.6 The clinical presentation is similar to that seen in endemic areas, but the percentage of icteric hepatitis seems to be higher. Older age and pre-existing chronic liver disease may explain the poorer prognosis in contrast to endemic countries.69

Until recently, hepatitis E (as hepatitis A) was considered a self-limiting disease, whose worst outcome was acute liver failure. However, since 2008, an increasing number of chronic infections by HEV have occurred in immunocompromised patients, such as HIV-infected individuals,24.–34 patients with hematologic disorders receiving chemotherapy,35.–37 and solid organ transplant recipients.7.–23 The importance of these chronic infections is related to the development of hepatic fibrosis and the risk of progression to cirrhosis.70.–72 The mechanisms of acquisition of the infection in these patients are uncertain. Reactivation of a latent infection seems not to play a role.73,74 In a study performed in solidorgan transplant recipients in France, the only independent factor associated with HEV infection was consumption of game meat,75 suggesting that zoono-tic transmission is the main mode of acquisition.

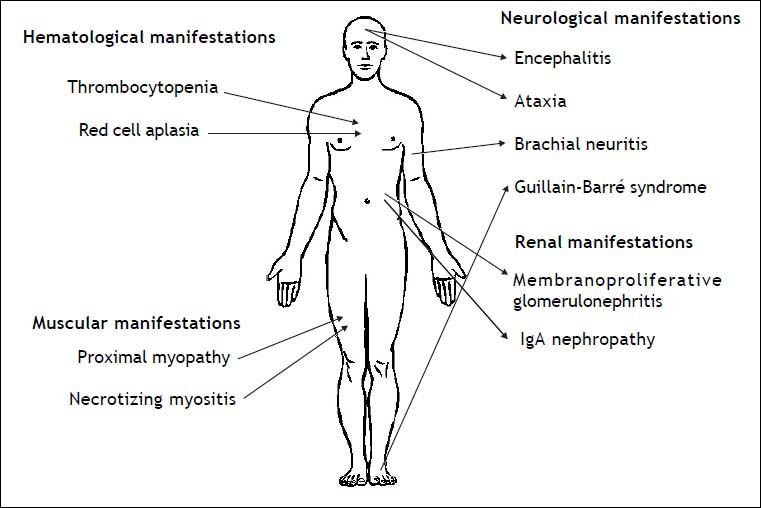

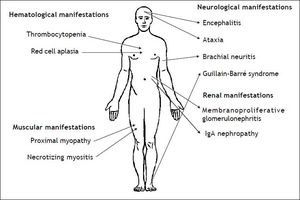

Infection by HEV genotype 3 in immunosuppres-sed patients has been related to several extrahepatic manifestations, which are summarized in figure 2. The first neurological manifestation described in relation to HEV infection was an isolated case of Guillain-Barré syndrome.76 Between 2004 and 2009, up to 5.5% of neurologic complications were reported in a series of 126 patients in two hospitals in the United Kingdom and France.77 These manifestations included inflammatory polyradiculopathy, Guillain-Barré syndrome, bilateral brachial neuritis, encephalitis, and ataxia/proximal myopathy. A case of Guillain-Barré syndrome associated with severe necrotizing myositis was recently reported in a liver transplant patient with acute HEV infection, who recovered after treatment with ribavirin.78 As to renal manifestations, membranoproliferative glo-merulonephritis and relapses of IgA nephropathy have been related to HEV infection in kidney and liver transplant patients.18 Most of these patients had cryoglobulinemia that became negative after spontaneous HEV clearance or after antiviral treatment. Kidney function improved and proteinuria decreased after HEV clearance. As in hepatitis A, hepatitis E infection has been related to hema-tological disorders, such as severe thrombocyto-penia79 and pure red cell aplasia.80,81

Diagnosis of Hev: LimitationsMembership of the four main HEV genotypes in a single serotype has facilitated the development of enzyme-linked immunoassays (ELISA) that are useful for universal diagnosis. These assays can detect specific IgG and IgM antibodies, regardless of HEV genotype. IgM antibodies appear in the acute phase of the infection, early at the end of the incubation period or when jaundice appears. IgM antibodies are an adequate marker for acute infection, as they remain detectable for 4 to 5 months.82 However, it should be noted that detection of HEV IgM presents specificity (78–98%) and sensitivity (72–98%) problems. HEV-RNA detection is the best marker for diagnosing acute hepatitis E infection,83 but HEV-RNA is only present during the short duration of the viremia period (around 2 weeks in serum and 4–12 weeks in stools). Thus, a lack of HEV RNA does not exclude the diagnosis of acute hepatitis E. Moreover, the majority of reverse-transcriptase PCR techniques for HEV-RNA determination are neither marketed nor standardized; hence, their interpretation and comparison are difficult.

Laboratory diagnosis of acute hepatitis E is based on the presence of HEV IgM in serum and/or detection of HEV-RNA in serum or stools. In acute infection, HEV IgM and even IgG can be detected, although detection of IgG antibodies alone indicates past infection. Therefore, IgG detection is useful for prevalence studies. Regarding immunosuppres-sed patients, it is essential to determine HEV-RNA because the antibodies may appear late or even be absent.

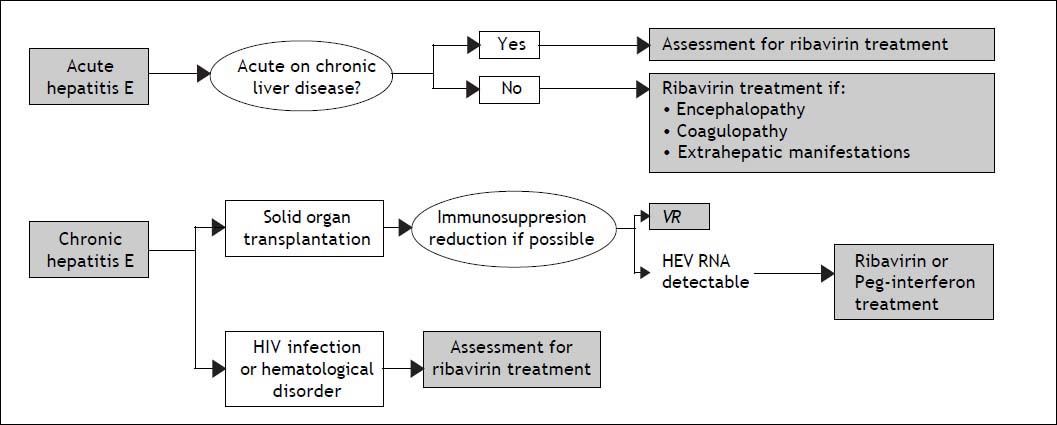

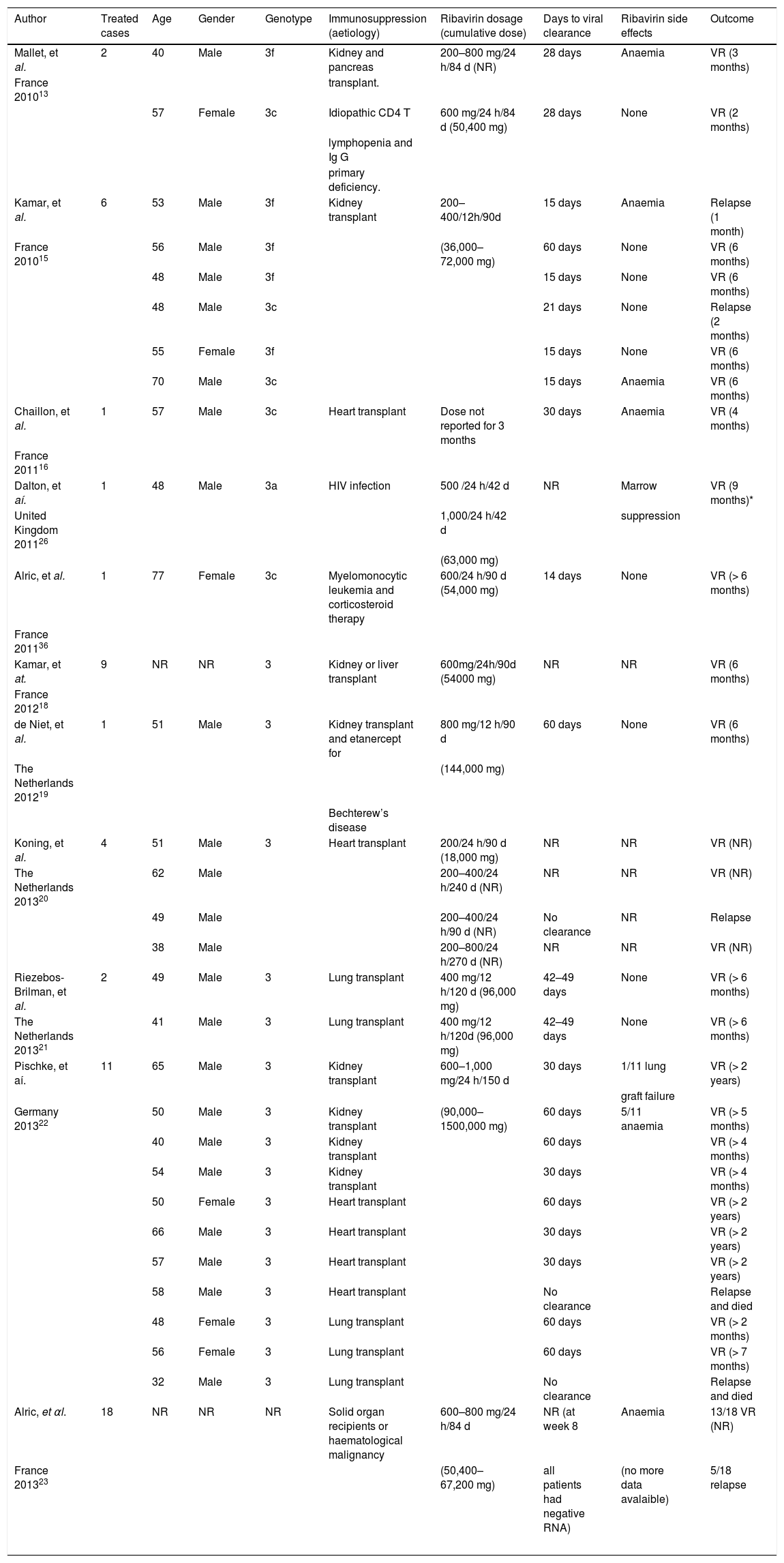

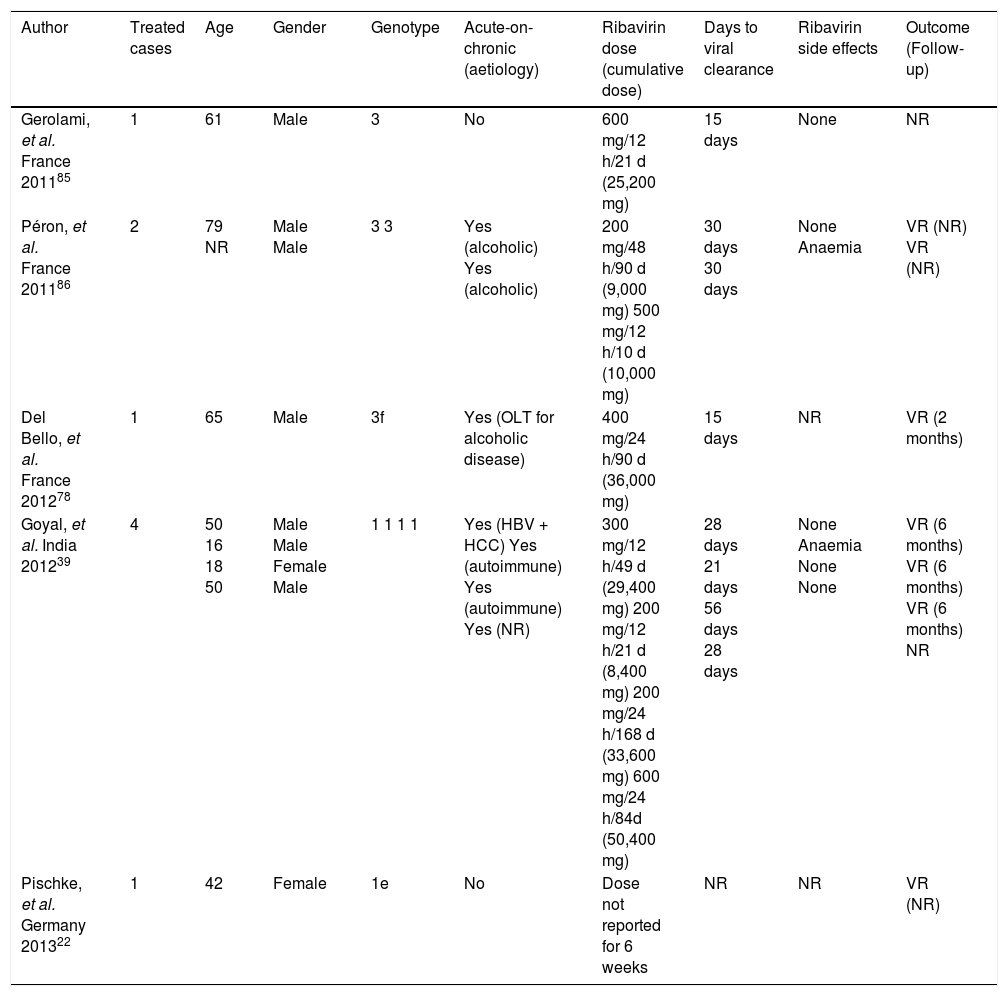

Management Of Acute And Chronic Hepatitis E: When and how to Treat?The majority of acute hepatitis E infections resolve spontaneously and therefore, treatment is not indicated. The factor associated with a risk of developing chronic hepatitis E is immunosupression. Therefore, the first step in the management of chronic hepatitis E in immunocompromised patients is a reduction in the immunosuppressive therapy regimen, if it is possible.84 There is no specific recommended therapy for hepatitis E. However, two drugs have been used: pegylated interferon-alpha 2a or 2b and ribavirin. This last seems to be the most useful, or at least the most widely used drug for treating both acute and chronic hepatitis E. However the number of patients treated in this way is still small and very heterogenous. Ribavirin has proven to suppress HEV in different populations: HEV infection after liver or kidney transplantation,13,15.–18 patients with hematologic neoplasms,36 and those with lymphocytopenia, both idiopathic and secondary to HIV infection.13,26 The majority of cases treated with ribavirin achieved viral suppression during treatment (Table 1), with very few relapses after treatment discontinuation occurring in solid organ transplantation.15,20,22,23 Nonetheless, the available follow-up is relatively short to know the true relapse rate. A recent study showed no difference in the rate of relapses between patients treated with ribavirin or peg-interferon for chronic hepatitis E infection, although only five patients received peg-interferon.23 Furthermore, the appropriate dose and duration of ribavirin treatment is unknown. Based on the currently available data, a proposal for diagnostic and therapeutic approaches in acute and chronic hepatitis E is suggested in figure 3. The timing of therapy initiation also remains to be defined.

Chronic hepatitis Ε cases treated with ribavirin.

| Author | Treated cases | Age | Gender | Genotype | Immunosuppression (aetiology) | Ribavirin dosage (cumulative dose) | Days to viral clearance | Ribavirin side effects | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mallet, et al. | 2 | 40 | Male | 3f | Kidney and pancreas | 200–800 mg/24 h/84 d (NR) | 28 days | Anaemia | VR (3 months) |

| France 201013 | transplant. | ||||||||

| 57 | Female | 3c | Idiopathic CD4 Τ | 600 mg/24 h/84 d (50,400 mg) | 28 days | None | VR (2 months) | ||

| lymphopenia and Ig G | |||||||||

| primary deficiency. | |||||||||

| Kamar, et al. | 6 | 53 | Male | 3f | Kidney transplant | 200–400/12h/90d | 15 days | Anaemia | Relapse (1 month) |

| France 201015 | 56 | Male | 3f | (36,000–72,000 mg) | 60 days | None | VR (6 months) | ||

| 48 | Male | 3f | 15 days | None | VR (6 months) | ||||

| 48 | Male | 3c | 21 days | None | Relapse (2 months) | ||||

| 55 | Female | 3f | 15 days | None | VR (6 months) | ||||

| 70 | Male | 3c | 15 days | Anaemia | VR (6 months) | ||||

| Chaillon, et al. | 1 | 57 | Male | 3c | Heart transplant | Dose not reported for 3 months | 30 days | Anaemia | VR (4 months) |

| France 201116 | |||||||||

| Dalton, et aí. | 1 | 48 | Male | 3a | HIV infection | 500 /24 h/42 d | NR | Marrow | VR (9 months)* |

| United Kingdom 201126 | 1,000/24 h/42 d | suppression | |||||||

| (63,000 mg) | |||||||||

| Alric, et al. | 1 | 77 | Female | 3c | Myelomonocytic leukemia and corticosteroid therapy | 600/24 h/90 d (54,000 mg) | 14 days | None | VR (> 6 months) |

| France 201136 | |||||||||

| Kamar, et at. | 9 | NR | NR | 3 | Kidney or liver transplant | 600mg/24h/90d (54000 mg) | NR | NR | VR (6 months) |

| France 201218 | |||||||||

| de Niet, et al. | 1 | 51 | Male | 3 | Kidney transplant and etanercept for | 800 mg/12 h/90 d | 60 days | None | VR (6 months) |

| The Netherlands 201219 | (144,000 mg) | ||||||||

| Bechterew’s disease | |||||||||

| Koning, et al. | 4 | 51 | Male | 3 | Heart transplant | 200/24 h/90 d (18,000 mg) | NR | NR | VR (NR) |

| The Netherlands 201320 | 62 | Male | 200–400/24 h/240 d (NR) | NR | NR | VR (NR) | |||

| 49 | Male | 200–400/24 h/90 d (NR) | No clearance | NR | Relapse | ||||

| 38 | Male | 200–800/24 h/270 d (NR) | NR | NR | VR (NR) | ||||

| Riezebos-Brilman, et al. | 2 | 49 | Male | 3 | Lung transplant | 400 mg/12 h/120 d (96,000 mg) | 42–49 days | None | VR (> 6 months) |

| The Netherlands 201321 | 41 | Male | 3 | Lung transplant | 400 mg/12 h/120d (96,000 mg) | 42–49 days | None | VR (> 6 months) | |

| Pischke, et aí. | 11 | 65 | Male | 3 | Kidney transplant | 600–1,000 mg/24 h/150 d | 30 days | 1/11 lung | VR (> 2 years) |

| graft failure | |||||||||

| Germany 201322 | 50 | Male | 3 | Kidney transplant | (90,000–1500,000 mg) | 60 days | 5/11 anaemia | VR (> 5 months) | |

| 40 | Male | 3 | Kidney transplant | 60 days | VR (> 4 months) | ||||

| 54 | Male | 3 | Kidney transplant | 30 days | VR (> 4 months) | ||||

| 50 | Female | 3 | Heart transplant | 60 days | VR (> 2 years) | ||||

| 66 | Male | 3 | Heart transplant | 30 days | VR (> 2 years) | ||||

| 57 | Male | 3 | Heart transplant | 30 days | VR (> 2 years) | ||||

| 58 | Male | 3 | Heart transplant | No clearance | Relapse and died | ||||

| 48 | Female | 3 | Lung transplant | 60 days | VR (> 2 months) | ||||

| 56 | Female | 3 | Lung transplant | 60 days | VR (> 7 months) | ||||

| 32 | Male | 3 | Lung transplant | No clearance | Relapse and died | ||||

| Alric, et αl. | 18 | NR | NR | NR | Solid organ recipients or haematological malignancy | 600–800 mg/24 h/84 d | NR (at week 8 | Anaemia | 13/18 VR (NR) |

| France 201323 | (50,400–67,200 mg) | all patients had negative RNA) | (no more data avalaible) | 5/18 relapse | |||||

D: days. HEV: hepatitis Ε virus. NR: not reported. RNA: ribonucleic acid. VR: virologic response.

Concerning acute infection in the setting of chronic liver disease, many studies have shown a poor prognosis for acute hepatitis E.84.–86 A study in France87 reported severe cases of fulminant acute infection, with hepatic encephalopathy and a high mortality rate. Active alcohol abuse and chronic liver disease were more frequent in patients suffering from the severe form. In another series of 28 cases of locally acquired hepatitis E in the United Kingdom,88 there were two deaths due to liver failure. These two patients were older men with history of alcohol abuse and previously undiagnosed cirrhosis, highlighting the importance of acute-on-chronic liver failure due to HEV. The experience of ribavirin use for acute hepatitis E therapy is shown in table 2.

Acute hepatitis Ε cases treated with ribavirin.

| Author | Treated cases | Age | Gender | Genotype | Acute-on-chronic (aetiology) | Ribavirin dose (cumulative dose) | Days to viral clearance | Ribavirin side effects | Outcome (Follow-up) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gerolami, et al. France 201185 | 1 | 61 | Male | 3 | No | 600 mg/12 h/21 d (25,200 mg) | 15 days | None | NR |

| Péron, et al. France 201186 | 2 | 79 NR | Male Male | 3 3 | Yes (alcoholic) Yes (alcoholic) | 200 mg/48 h/90 d (9,000 mg) 500 mg/12 h/10 d (10,000 mg) | 30 days 30 days | None Anaemia | VR (NR) VR (NR) |

| Del Bello, et al. France 201278 | 1 | 65 | Male | 3f | Yes (OLT for alcoholic disease) | 400 mg/24 h/90 d (36,000 mg) | 15 days | NR | VR (2 months) |

| Goyal, et al. India 201239 | 4 | 50 16 18 50 | Male Male Female Male | 1 1 1 1 | Yes (HBV + HCC) Yes (autoimmune) Yes (autoimmune) Yes (NR) | 300 mg/12 h/49 d (29,400 mg) 200 mg/12 h/21 d (8,400 mg) 200 mg/24 h/168 d (33,600 mg) 600 mg/24 h/84d (50,400 mg) | 28 days 21 days 56 days 28 days | None Anaemia None None | VR (6 months) VR (6 months) VR (6 months) NR |

| Pischke, et al. Germany 201322 | 1 | 42 | Female | 1e | No | Dose not reported for 6 weeks | NR | NR | VR (NR) |

D: days. HEV: hepatitis Ε virus. NR: not reported. RNA: ribonucleic acid. VR: virologie response.

Improvements in the sanitary infrastructure and availability of clean drinking water may be the key prevention strategy to avoid hepatitis E transmission in developing areas. In industrialized countries, it seems evident that most cases of native hepatitis E may be related to zoonotic transmission of infection,53 which can be responsible for hepatic fibrosis and even cirrhosis, mainly in immunocom-promised patients. For this reason, it is vital to reinforce the recommendations for systematic cooking of pork (heating at 71° for at least 20 min) and avoiding raw meat if the cooking advice cannot be guaranteed.89 Another basic issue with regard to immunocompromised patients is blood donation. Several cases of HEV transmission through blood products have been reported world-wide.48.–51 Although approximately 22% of blood donors from a sample in the United States presented positive serology for anti-HEV antibody, HEV-RNA was not detected and there were no reports of HEV infection.90 Hence, blood transmission exists, but its prevalence seems to be very low.

It is known that recovery from HEV infection results in protective immunity by neutralizing antibodies that can be detected in serum of individuals exposed to HEV, whatever the human genotype.91 Protective immunity can also be induced by HEV vaccination. In 2007, a recombinant HEV vaccine developed by GlaxoSmith-Kline was tested in 2000 healthy Nepalese men susceptible to HEV infection included in a Phase II study. After 3 doses, 95.5% of subjects developed anti-HEV antibodies,92 albeit this vaccine has not been further developed. A phase III study performed in China involving 112,604 participants in Jiangsu Province, where genotypes 3 and 4 are predominant, revealed an efficacy > 99% in preventing clinical hepatitis E among persons who completed the full 3-dose series of HEV 239 compared with placebo.93 However, it should be noted that this vaccine is based on HEV genotype 1, and its efficacy against genotype 3 is unknown. In addition, the vaccine requires further information in special risk groups, such as patients with chronic liver disease and immunocompromised individuals. Regarding pregnant women, though information on the safety and efficacy of HEV 239 in this group is limited since pregnant women were excluded from the trial, a post hoc analysis of 68 participants whose pregnancies were detected after receiving 1 to 3 doses of vaccine or placebo rules out an increased risk of spontaneous abortion or congenital anomalies.94 This vaccine has been licensed by the State Food and Drug Administration of China since January 2012, so new data on efficacy may be available in the next few years.

Abbreviations- •

HEV: hepatitis E virus.

- •

HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

- •

ORF: open reading frames.

- •

RNA: ribonucleic acid.

- •

VR: virologic response.

There is no commercial affiliation or author consultancy that could be construed as a conflict of interest with respect to the submitted data.