Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection and treatment impact the patient's daily life and work productivity. Until recently, treatments were associated with side effects and insufficient virologic and hepatic results.

This study evaluated fatigue, work productivity, and treatment modalities in patients with HCV infection.

Materials and methodsThis cross-sectional, non-interventional, multicenter study was conducted in real-life settings between March and December 2015 at 109 sites in France.

ResultsData from 1269 patients were evaluable. The mean patient age was 55.8±12.5 years; 53.3% (676) patients were male. A total of 80.1% (1015) of patients were Caucasian and 62.3% (791) had a genotype 1 infection, 34.2% (433) had at least one comorbidity and 15.6% (198) had ≥1 clinical sign/symptom. Illicit drug use was the main route of HCV transmission and accounted for 36.8% (466) of all infections. Fibrosis stage F0/F1 was reported in 41.4% (525) of patients. A majority of patients (60.4%, 764) had never been treated. In patients previously treated, 85.8% (430) received ribavirin and pegylated interferon and only 13.4% (67) direct-acting antivirals.

The mean percent of global impairment due to health was highest (34.8±30.9%) in patients 18–45 years of age. The prevalence of active employed patients with a total fatigue score≥its median value (45/160) was 38.6%. The mean percent work time missed due to health was 9.6±23.6% for working patients of 18–45 years of age and 7.3±21.8% for working patients of 45–65 years of age. The mean overall prevalence of employed patients with impairment due to health issues was 21.8±26.8%. The prevalence of patients with a reduced work activity of ≥50% due to their health status was 32.1%.

ConclusionThese data reinforce the request for improved disease management in France, allowing patients with HCV infection to increase work productivity, reduce fatigue, and, hopefully, cure their disease.

In 2013, 18 million people worldwide were estimated to be chronically infected by Hepatitis C virus (HCV) HCV [1].

The clinical expression of HCV infection is extremely variable [2,3]. Whereas some patients are asymptomatic for years, others may develop an array of symptoms with variable intensity in relation to chronic liver injury or extrahepatic complications [4–6]. The most frequent symptoms are fatigue, brain concentration disturbance, anxiety, depression, rheumatologic pain, and digestive disorders [7,8]. As a consequence, quality of life (QoL) and working capacity are impacted [8]. Interferon, ribavirin and first-generation protease inhibitors were the preferred treatment for patients with HCV infection and were associated with numerous side effects, insufficient virologic response and hepatic results, as well as decreased quality of life [9–11]. Today, direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), which have a much better risk–benefit ratio have been made available [12].

The effect of HCV infection on QoL, the development of psychological disorders, loss of energy, and decreased working capacity of patients with the disease can be measured using different methods and scales of assessment [13,14].

Studies addressing QoL and the impact on working capacity have been performed over the past several years in selected populations in centers specialized in HCV care [12,15,16]. However, these studies did not explore QoL or work productivity issues in a representative cohort of the general population and in real-world settings.

In 2004, a study collected epidemiologic data from HCV patients in France [17]. At that time, the prevalence of HCV infection was estimated at 0.84%, corresponding to approximately 367,055 patients. Almost two-thirds of patients (65%) were viremic. Thus, in 2004, the prevalence of patients with chronic HCV infection in France was 0.53% and did not provide data about the impact on fatigue and work productivity [18]. In 2017, another study was published by Marcellin et al. [19]. For this study, patients were only recruited in expert centers.

Thus, the present real-life study was conducted to evaluate work productivity, activity impairment and fatigue in patients with chronic HCV infection who were naïve or treatment-free on the day of inclusion in a representative French nationwide cohort.

2Materials and methods2.1SettingsThis epidemiologic, cross-sectional, non-interventional, multicenter study was conducted in real-life settings from March 2015 until December 2015 at 109 study sites in France using self-administered questionnaires. No follow-up was planned for this study.

To avoid selection bias and to allow for the most representative sample of hepato-gastroenterologists, only hepato-gastroenterologists or infectious disease specialists cited on the CEGEDIM list (Centre de Gestion et de Documentation de l’Information Médicale, 4264 physicians from general hospital structures and private practice in metropolitan France) and involved in the management of HCV infection were recruited.

The study complied with all local legal requirements and received approval from the French ethics committee prior to the collection of any patient data. Patients who met the selection criteria provided written informed consent prior to inclusion into the study.

2.2PopulationPatients of at least 18 years of age, with an HCV infection with well-defined genotypes diagnosed at least 6 months before the study and confirmed by detectable serum HCV RNA, as well as positive serum anti-HCV antibodies, were eligible for inclusion. Patients had to be treatment-naïve or treatment-experienced but not on treatment for their HCV infection at the time of study initiation.

2.3Study endpointsStandard patient and disease characteristics, including HCV genotype, medical history, demographics, diagnosis, route of transmission, medical course, fibrosis stage (according to the METAVIR classification using FibroTest®, FibroScan®, FibroMeter™ (all Echosens, Paris – France) or biopsy), clinical signs and symptoms (limited to jaundice, gastrointestinal bleeding, ascites and encephalopathy), main comorbidities and treatment history were collected.

In addition, this study assessed work productivity and activity impairment using the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Hepatitis C (WPAI:HepC) questionnaire; fatigue was assessed using the Fatigue Impact Scale [13,14,20].

The WPAI:HepC questionnaire consists of 6 questions: 1=currently employed; 2=hours missed due to health problems; 3=hours missed due to other reasons; 4=hours actually worked; 5=degree health affected productivity while working (using a scale of 0–10 on a visual analog scale, VAS); and 6=degree health affected productivity in regular unpaid activities (assessed using a VAS). The recall period for questions 2–6 is generally 7 days.

The Fatigue Impact Scale is a self-reported outcome instrument designed to measure the effect of fatigue on the activities of daily living. The scale rates how much of a problem fatigue has caused during the past month. There are 40 items, each of which is scored from 0 (no problem) to 4 (extreme problems), providing a continuous scale of 0 to 160. It is composed of three subscales that describe how fatigue impacts cognitive functioning (10 items), psychosocial functioning (20 items), and physical functioning (10 items). Cognitive functioning includes concentration, memory, thinking and organization of thoughts. Psychosocial functioning includes the impact of fatigue upon isolation, emotions, workload, and coping. Physical functioning includes motricity, effort, stamina, and coordination.

2.4Statistical analysisA descriptive statistical analysis, using SAS® version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was conducted using the collected data. A subgroup analysis was performed for patients with a HCV/hepatitis B virus co-infection.

Factors associated with outcomes of the analysis of the WPAI:HepC questionnaire (score of at least 50%) and the fatigue impact assessment (score ≤80/160) were selected using logistic regression models. Multivariable logistic regression analysis, applying backward elimination, was used to investigate factors associated with outcomes of the analysis of the WPAI:HepC questionnaire (score of at least 50%) and the fatigue impact assessment (score ≤80/160). Risk factors appearing as statistically significant (p<0.20) in the univariate logistic regressions were used to obtain an initial multivariable logistic regression fit. Terms not appearing as statistically significant using the likelihood ratio test (p<0.05) were removed from the multivariable logistic regression model on a one-by-one basis. All risk factors in the final fitted model are presented as odds ratio (OR) with accompanying 95% confidential intervals (CI).

3Results3.1Patient and disease characteristicsIn total, 1311 patients with HCV infection were enrolled; data from 1269 patients were evaluable. A total of 42 patients were excluded from the analysis: eight patients had been diagnosed less than six months before study inclusion and 34 patients did not have a specified genotype. All patients had positive HCV-RNA.

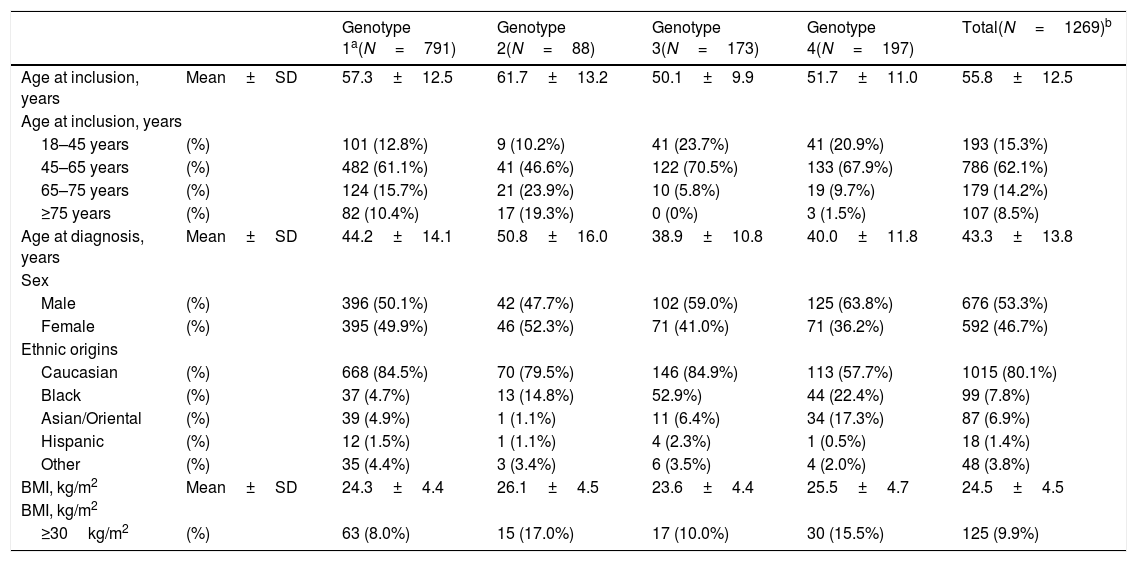

At study inclusion, the mean patient age was 55.8±12.5 years; 53.3% (676) of patients were men. A majority of patients (62.1%, 786) were 45–65 years of age. The mean body mass index was 24.5±4.5kg/m2 and 80.1% (1015) of patients were Caucasian. As expected, a majority of patients (62.3% (791), 95% CI, 59.7–65.0) had a genotype 1 infection (genotype 1a, 27.5% (348); genotype 1b 29.9% (378); genotype 1 other or non-specified, 4.9% (39)). Detailed patient characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Genotype 1a(N=791) | Genotype 2(N=88) | Genotype 3(N=173) | Genotype 4(N=197) | Total(N=1269)b | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at inclusion, years | Mean±SD | 57.3±12.5 | 61.7±13.2 | 50.1±9.9 | 51.7±11.0 | 55.8±12.5 |

| Age at inclusion, years | ||||||

| 18–45 years | (%) | 101 (12.8%) | 9 (10.2%) | 41 (23.7%) | 41 (20.9%) | 193 (15.3%) |

| 45–65 years | (%) | 482 (61.1%) | 41 (46.6%) | 122 (70.5%) | 133 (67.9%) | 786 (62.1%) |

| 65–75 years | (%) | 124 (15.7%) | 21 (23.9%) | 10 (5.8%) | 19 (9.7%) | 179 (14.2%) |

| ≥75 years | (%) | 82 (10.4%) | 17 (19.3%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1.5%) | 107 (8.5%) |

| Age at diagnosis, years | Mean±SD | 44.2±14.1 | 50.8±16.0 | 38.9±10.8 | 40.0±11.8 | 43.3±13.8 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | (%) | 396 (50.1%) | 42 (47.7%) | 102 (59.0%) | 125 (63.8%) | 676 (53.3%) |

| Female | (%) | 395 (49.9%) | 46 (52.3%) | 71 (41.0%) | 71 (36.2%) | 592 (46.7%) |

| Ethnic origins | ||||||

| Caucasian | (%) | 668 (84.5%) | 70 (79.5%) | 146 (84.9%) | 113 (57.7%) | 1015 (80.1%) |

| Black | (%) | 37 (4.7%) | 13 (14.8%) | 52.9%) | 44 (22.4%) | 99 (7.8%) |

| Asian/Oriental | (%) | 39 (4.9%) | 1 (1.1%) | 11 (6.4%) | 34 (17.3%) | 87 (6.9%) |

| Hispanic | (%) | 12 (1.5%) | 1 (1.1%) | 4 (2.3%) | 1 (0.5%) | 18 (1.4%) |

| Other | (%) | 35 (4.4%) | 3 (3.4%) | 6 (3.5%) | 4 (2.0%) | 48 (3.8%) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | Mean±SD | 24.3±4.4 | 26.1±4.5 | 23.6±4.4 | 25.5±4.7 | 24.5±4.5 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||||

| ≥30kg/m2 | (%) | 63 (8.0%) | 15 (17.0%) | 17 (10.0%) | 30 (15.5%) | 125 (9.9%) |

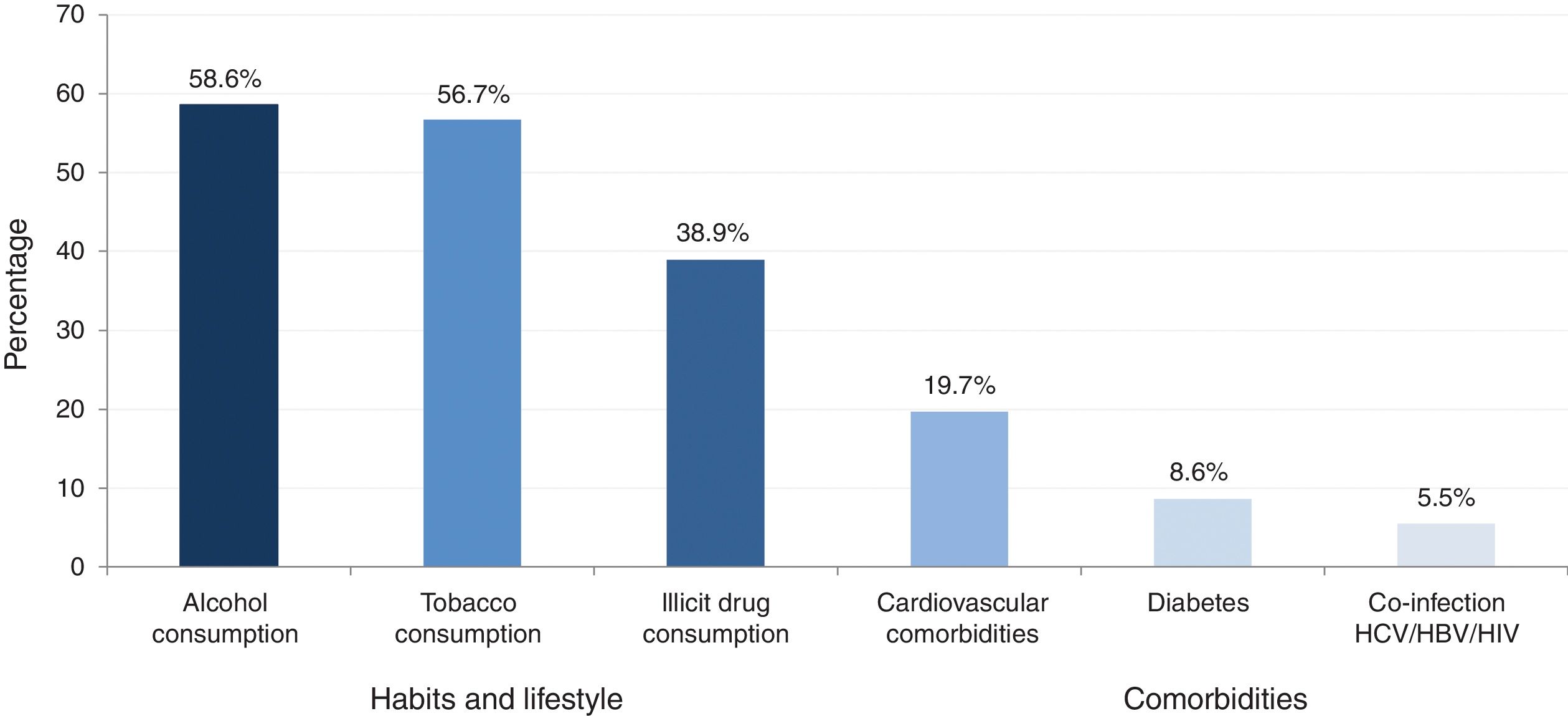

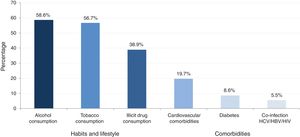

A total of 34.2% (433) of patients presented with at least one comorbidity and 15.6% (197) of patients presented with at least one clinical sign/symptom. The prevalence of major comorbidities (cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, obesity/metabolic syndrome and co-infections), habits and lifestyle (alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug consumption) is provided in Fig. 1.

Prevalence of habits, lifestyle and major comorbidities.

Alcohol consumption: elevated consumption (>21glasses/week)+current low consumption and high past consumption or low consumption in the past and low actual and no past consumption.

Tobacco use: actual smoker and former smoker.

Illicit drug consumption: drugs actually and drug only in the past.

Major comorbidities >5%.

Illicit drug use was the main route of HCV transmission and accounted for 36.8% (466) of all infections. A total of 11% of patients (139) were current illicit drug users; 6.5% (9) consumed intravenously illicit drugs. Conversely, 27.9% (353) reported only past illicit drug use (intravenous (IV) and non-IV routes).

Substitute treatments were reported for 8.4% (106) of the patients. Infection due to blood transfusion was reported for 21.5% (272) of all patients.

Initial HCV diagnosis was mainly (57.2%, 725) provided by general practitioners and 8.7% (111) of the patients had a biopsy performed. Fibrosis stage F0/F1 was reported for 41.4% (525) of the patients, 38.2% (475) had fibrosis stage F2 or F3, and 20.5% (258) had fibrosis stage F4.

The majority of patients (60.4%, 764) had never received treatment for HCV infection. In those patients who were previously treated, 65.8% (430) received ribavirin and pegylated interferon and 13.4% (67) DAA therapy.

Of the 39.3% (495) of patients with fibrosis stage F3 or F4, 52.1% (257) had never been treated for their infection. Among them, 47.9% (115) were waiting for an interferon-free treatment. For 23.3% (56) of the patients this was the physician's choice, 22.1% (53) refused treatment, 5.0% (12) had contraindications to treatment, and four patients (1.7%) were non-eligible according to current reimbursement policies of the French health authorities.

The prevalence of patients with HCV/HBV or HIV co-infection was 7% (88). Within this patient group, the majority were male (59.8%, 52) and older than 50 years of age; 66.6% (58) of the patients were former or current smokers, 56.2% (49) currently consumed alcohol or had done so in the past, and 60.9% (53) of the patients currently consumed illicit drugs or had done so in the past. Overall, 54.0% (47) of co-infected patients had fibrosis stage F0 or F1, 33.3% (29) had fibrosis stage F2 or F3, and 12.6% (11) had fibrosis stage F4. In total, 59.1% (52) of the patients had never been treated and 38.5% (20) of the patients were waiting for an interferon-free treatment, while 17.3% (9) of patients refused treatment.

3.2Work productivity and activity impairment questionnaireOverall, 57.3% (710) of all patients were unemployed; 63.8% (453) of these patients were of working age (18–65 years).

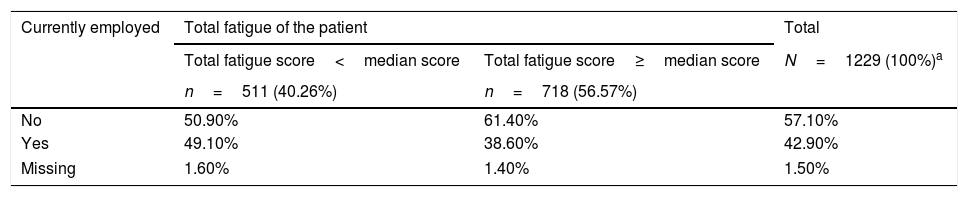

The mean percent of global impairment due to health was highest (34.8±30.9%) in patients 18–45 years of age. Moreover, the mean percent of global impairment was 5-times higher in patients feeling tired (47.2±28.4%) than in those feeling less tired (9.6±16.6%). The prevalence of active employed patients with a total fatigue score≥its median value (45.0/160.0) was 38.6%. The total fatigue score of patients who were currently employed is detailed in Table 2.

Prevalence of inactive and active patients according to the total fatigue of the patient (fatigue impact scale questionnaire).

| Currently employed | Total fatigue of the patient | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total fatigue score<median score | Total fatigue score≥median score | N=1229 (100%)a | |

| n=511 (40.26%) | n=718 (56.57%) | ||

| No | 50.90% | 61.40% | 57.10% |

| Yes | 49.10% | 38.60% | 42.90% |

| Missing | 1.60% | 1.40% | 1.50% |

The mean percent work time missed due to health was 9.6±23.6% for patients 18–45 years of age and 7.3±21.8% for patients 45–65 years of age. It was 6-times higher in those patients feeling more tired (13.0±27.5%) than in those feeling less (2.2±12.9%). The mean percent overall work impairment due to health was 5-times higher (38.9±32.0%) than patients in the latter group (7.8±17.6%).

3.2.1At workThe mean percent impairment while working due to health was 21.8±26.8%. It was higher in patients older than 75 years of age (53.3±50.3%) and almost the same for patients between 18 and 45 (21.4±27.6%) and between 45 and 65 years of age (21.6±26.3%); it was nearly 6-times higher in patients feeling more tired (36.4±28.3%) than in those feeling less tired (6.3±12.9%).

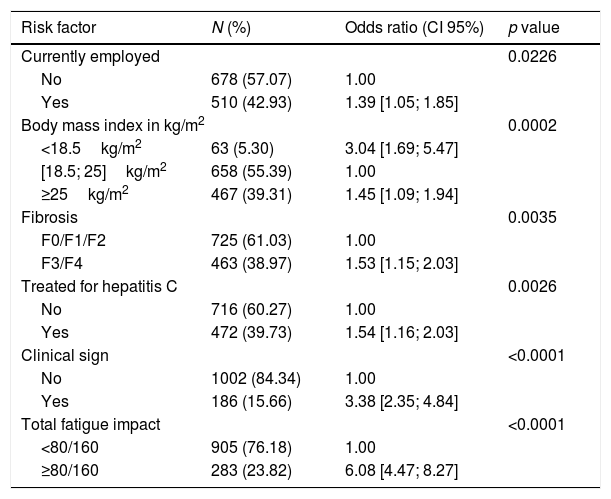

3.2.2Patients with work impairment of at least 50%The prevalence of patients with a reduced work activity of at least 50% due to their health status was 32.2%. Factors associated with the highest impact included a fatigue score of at least 80.0/160.0 (6.08; 95% CI, 4.47–8.27), having at least one clinical sign/symptom (3.38; 95% CI, 2.35–4.84), and those with a body mass index of less than 18.5kg/m2 (3.04; 95% CI, 1.69–5.47). A fatigue score of at least 80.0/160.0 was most often observed in patients with at least one clinical sign/symptom (odds ratio, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.31–2.67) and in patients with a worsening of at least 50% of their activities due to health status (odds ratio, 6.06; 95% CI, 4.52–8.13).

The main factors impacting work activity are detailed in Table 3.

Associated risk factors with the alteration of ≥50% of activity impairment due to health, multivariate analysis: logistic regression (evaluable population, n=1188).

| Risk factor | N (%) | Odds ratio (CI 95%) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Currently employed | 0.0226 | ||

| No | 678 (57.07) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 510 (42.93) | 1.39 [1.05; 1.85] | |

| Body mass index in kg/m2 | 0.0002 | ||

| <18.5kg/m2 | 63 (5.30) | 3.04 [1.69; 5.47] | |

| [18.5; 25]kg/m2 | 658 (55.39) | 1.00 | |

| ≥25kg/m2 | 467 (39.31) | 1.45 [1.09; 1.94] | |

| Fibrosis | 0.0035 | ||

| F0/F1/F2 | 725 (61.03) | 1.00 | |

| F3/F4 | 463 (38.97) | 1.53 [1.15; 2.03] | |

| Treated for hepatitis C | 0.0026 | ||

| No | 716 (60.27) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 472 (39.73) | 1.54 [1.16; 2.03] | |

| Clinical sign | <0.0001 | ||

| No | 1002 (84.34) | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 186 (15.66) | 3.38 [2.35; 4.84] | |

| Total fatigue impact | <0.0001 | ||

| <80/160 | 905 (76.18) | 1.00 | |

| ≥80/160 | 283 (23.82) | 6.08 [4.47; 8.27] | |

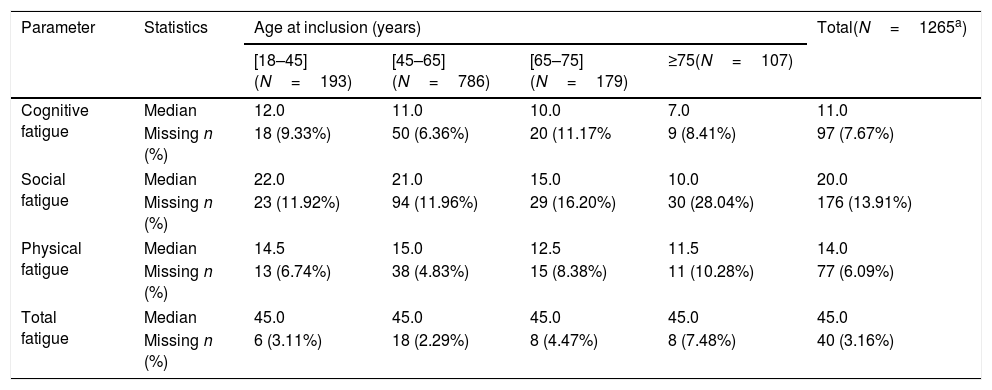

The overall median total fatigue score was 45.0/160.0. Details are provided in Table 4.

Fatigue impact scale according to age at inclusion (years) – evaluable population.

| Parameter | Statistics | Age at inclusion (years) | Total(N=1265a) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [18–45](N=193) | [45–65](N=786) | [65–75](N=179) | ≥75(N=107) | |||

| Cognitive fatigue | Median | 12.0 | 11.0 | 10.0 | 7.0 | 11.0 |

| Missing n (%) | 18 (9.33%) | 50 (6.36%) | 20 (11.17% | 9 (8.41%) | 97 (7.67%) | |

| Social fatigue | Median | 22.0 | 21.0 | 15.0 | 10.0 | 20.0 |

| Missing n (%) | 23 (11.92%) | 94 (11.96%) | 29 (16.20%) | 30 (28.04%) | 176 (13.91%) | |

| Physical fatigue | Median | 14.5 | 15.0 | 12.5 | 11.5 | 14.0 |

| Missing n (%) | 13 (6.74%) | 38 (4.83%) | 15 (8.38%) | 11 (10.28%) | 77 (6.09%) | |

| Total fatigue | Median | 45.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 | 45.0 |

| Missing n (%) | 6 (3.11%) | 18 (2.29%) | 8 (4.47%) | 8 (7.48%) | 40 (3.16%) | |

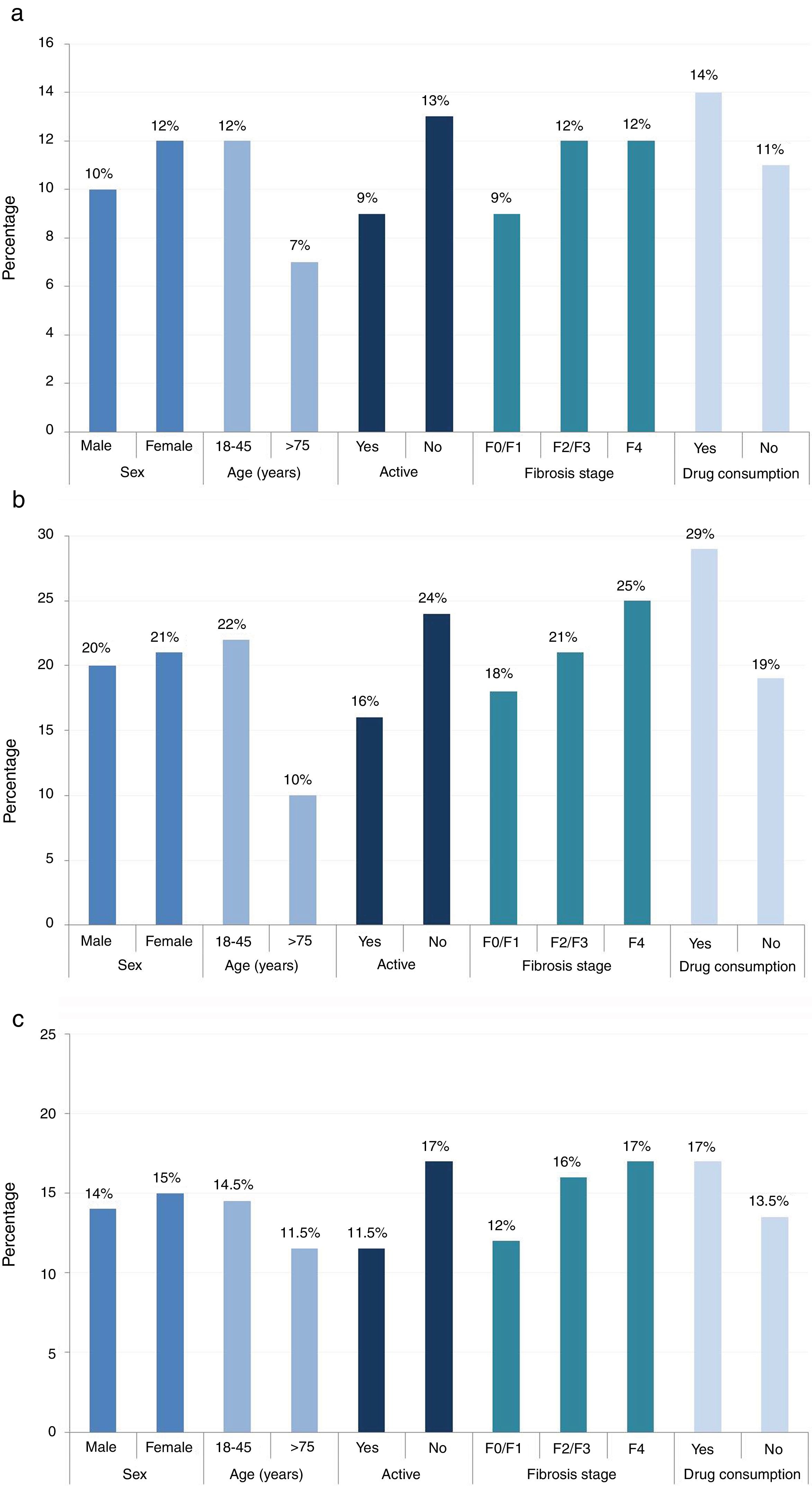

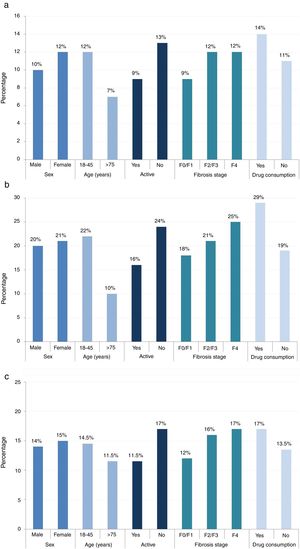

The cognitive and social fatigue impact scores (12.0/40.0 and 22/80, respectively) were the highest in patients between 18 and 45 years of age (compared with the physical impact score, which was highest for patients between 45 and 65 years of age [15.0/40.0]). Median scores for cognitive, social, and physical fatigue per sex, age, activity, fibrosis stage, and current drug consumption are provided in Fig. 2.

All 3 fatigue scores were higher for women (cognitive, 12.0/40.0; social, 21.0/80.0; and physical, 15.0/40.0), inactive patients (cognitive, 13.0/40.0; social, 24.0/80.0; and physical, 17.0/40.0) and patients with drug consumption (cognitive, 14.0/40.0; social, 29.0/80.0; and physical, 17.0/40.0).

The highest cognitive fatigue score was observed in patients with fibrosis stage F2/F3/F4 (12.0/40.0). Conversely, patients with fibrosis stage F0/F1 had a score of 9.0/40.0. The social fatigue score was highest in patients with fibrosis stage F2/F3/F4 (22.0/80.0) and the lowest in patients with fibrosis stage F0/1 (18.0/80.0). The physical fatigue score was the highest in patients with fibrosis stage F2/F3/F4 (16.0/40.0) and lowest in patients with fibrosis stage F0/1 (12.0/40.0).

4DiscussionThis cross-sectional, epidemiologic study conducted in France in 2015 could confirm the negative impact of HCV infection and interferon – and ribavirin-based treatments on QoL, work productivity, activity, and fatigue in HCV patients.

Patients included were mainly between 45 and 65 years old, with no notable difference in prevalence between male and female patients. Not surprisingly, a large majority of the study patients were Caucasian, this being the predominant race in both France and Europe. As expected, patients were mainly infected by HCV genotype 1 infection (62.3%; 95% CI, 59.7–65.0). A majority of patients (57.3%, 710) were unemployed.

When analyzing the impact of HCV infection on work productivity, activity, and fatigue, results indicated that a majority of patients aged between 18 and 65 years, the so-called “active population” had the greatest work impairment and fatigue, especially cognitive fatigue. It is not surprising that work productivity and activity were most affected in patients reporting the highest levels of fatigue. Moreover, the study showed that fatigue was more prevalent in women and in patients consuming illicit drugs, thereby confirming past observations [12,20,21].

An in-depth analysis of the factors that may impact fatigue showed that a low body mass index, clinical signs/symptoms, and a worsening of health status, were the most often reported triggers of reduced work productivity and fatigue. Fatigue in patients with HCV was more common in patients between 18 and 45 years of age and in patients with a more severe fibrosis, confirming the results of Younossi in 2015 [22]. Therefore, this study confirms the work productivity impairment of patients with HCV infection in a real-world setting, resulting in an economic burden per employed patient that reached 2541€ in 2015 in France, with calculations based on an average prevalence of 7.7% of employed patients absent from work with an average annual wage of 33,001€ [23,24].

Absenteeism rates were assessed using the WPAI:HepC for the 7 days before the study visit. It was assumed that the same average rate was maintained throughout the year.

Due to the absence of DAA therapy in France until the end of 2014 and due to French health policy at that time, early interferon and ribavirin regimens were mainly prescribed to patients with severe fibrosis stages, resulting in a certain number of untreated patients [22,25]. Since then, DAAs have been made available, allowing for a replacement of interferon and ribavirin regimens. Moreover, due to changes in reimbursement strategies, HCV therapies for patients with less severe fibrosis stages are now reimbursed, which may reduce the economic burden and impact of the disease and treatment on patient QoL and work productivity. The high number of unemployed patients with HCV infection confirms the impact of disease on work productivity and patient QoL.

Even though this was a retrospective designed study, the present data collected in real-life settings allowed the recruitment of a large spectrum of patients, reflecting the current patient population in France. Generalizability to other countries is therefore limited, especially outside of the European Community or in countries with welfare programs and populations differing from that of France. Another limitation may be the fact that the study did not specifically consider the economic impact of HCV infection on impaired work productivity in patients treated with interferon and ribavirin as reported by Younossi et al. in 2017 [26]. This might have provided further supportive arguments for the prescription of DAA therapy. However, with the recent changes in the reimbursement strategy and the marketing authorization of DAAs, this information may no longer be required. Moreover, one may consider the fact that no reference hepatology center participated in this study, which could have biased study results. The study does, however, indicate that the majority of patients are diagnosed in local hepatology centers. This confirms that the chosen method of data collection in this study did provide reliable real-world data. Another issue may be that patient data were not analyzed according to treatment. Therefore, there is no confirmation that patients who previously received interferon treatment reported more psychological comorbidities or if results could have differed from those who received interferon-free treatments.

In conclusion, in France in 2015, the majority of patients with HCV were between 18 and 65 years of age, most had HCV genotype 1 infection, had cardiovascular comorbidities, and were unemployed, with limitations in daily work productivity and QoL. In addition to impaired work productivity and fatigue caused by HCV infection, patient-reported outcomes were also heavily impacted by HCV treatment. Now that new treatment options and guidelines are available in France, HCV disease may have a significantly lower impact on work activity and fatigue.

The present data reinforce the request for improved HCV disease management in France, allowing HCV infected patients to increase work productivity, and reduce fatigue. This is particularly important in active adults aged less than 45 years.AbbreviationsCEGEDIM Centre de Gestion et de Documentation de l’Information Médicale direct acting antiviral fibrosis hepatitis C virus intravenous quality of life ribonucleic acid visual analog scale Work Productivity and Activity Impairment Questionnaire: Hepatitis C

AbbVie provided financial support for this epidemiological study.

Conflict of interestThe authors received consultancy honoraria from AbbVie for this study. Employees of ITEC and Karl Patrick Göritz have no conflict of interest to disclose.

The authors would like to thank all the investigators who participated in this trial.

The authors wish to thank ITEC, France for conducting the statistical analysis and reviewing the manuscript.

Karl Patrick Göritz, SMWS, France provided medical writing and editing services in the development of this manuscript.

The financial support for these services was provided by AbbVie.