China is regarded as the “leader in liver diseases” because that one-fifth of the population was affected by some forms of liver diseases in this developing country. In addition to common infectious liver diseases (such as viral hepatitis and parasitic liver diseases), non-infectious liver diseases such as fatty liver diseases (FLD), drug-induced liver injury (DILI), alcoholic liver diseases (ALD), autoimmune liver diseases (AILD), vessel-related liver diseases, genetic metabolic liver diseases and liver masses are present. In recent years, an increasing number of liver diseases have been reported in special populations, including childhood liver diseases, pregnancy-related liver diseases and liver transplant-associated diseases and so on. Absence of characteristic symptoms and signs coupled with a lack of medical knowledge, patients with chronic liver diseases seek medical treatment without a reliable model, which resulted to the chaotic consult medical status in China mainland. This article aims to describe the current seek medical status of chronic liver diseases and discuss a stage-based consulting medical model for chronic liver diseases in China mainland, which would contribute to make rational use of limited medical resources and help to address National Health China 2030 strategy initiated by the Chinese government.

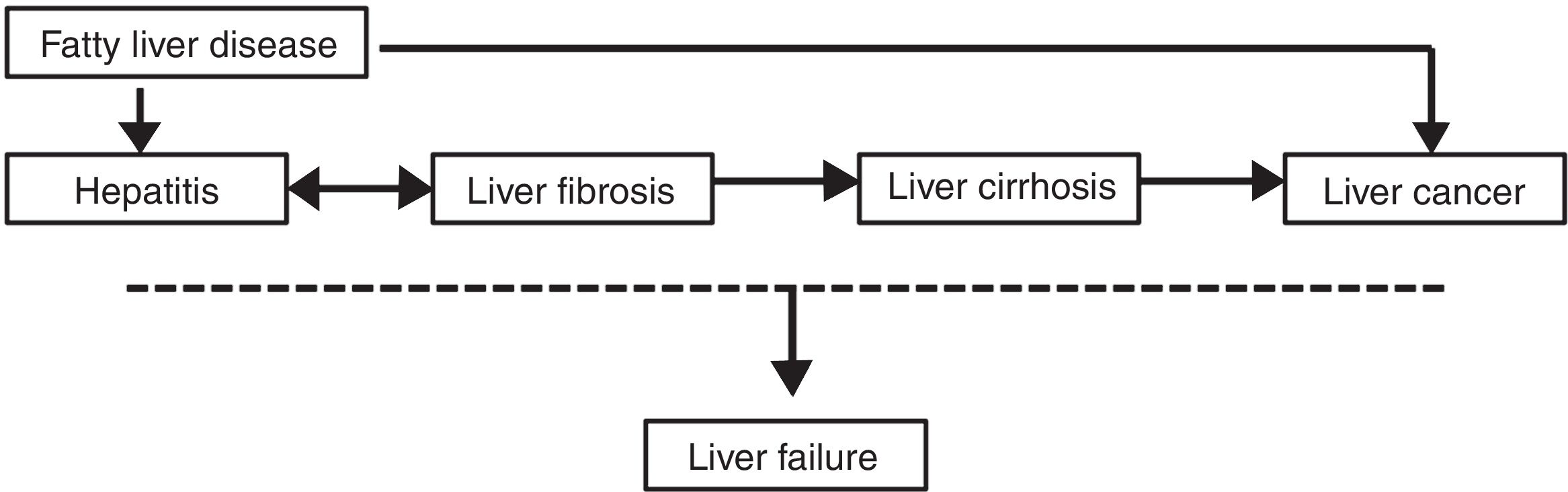

Chronic liver diseases (CLD) caused by various etiologies exhibits a common chronic progression, including chronic hepatitis, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis and liver cancer stage. As for fatty liver diseases (FLD), some cases can develop into liver cancer without progressing through the cirrhosis stage [1]. As a result, FLD is the most common cause of cryptogenic liver cancer [2]. In addition, at any stage in the occurrence and progression of these CLD, certain incentive factors (such as drug toxicity, alcohol consumption, bacterial infections, fatigue and viral infections) may lead to liver failure (see Fig. 1).

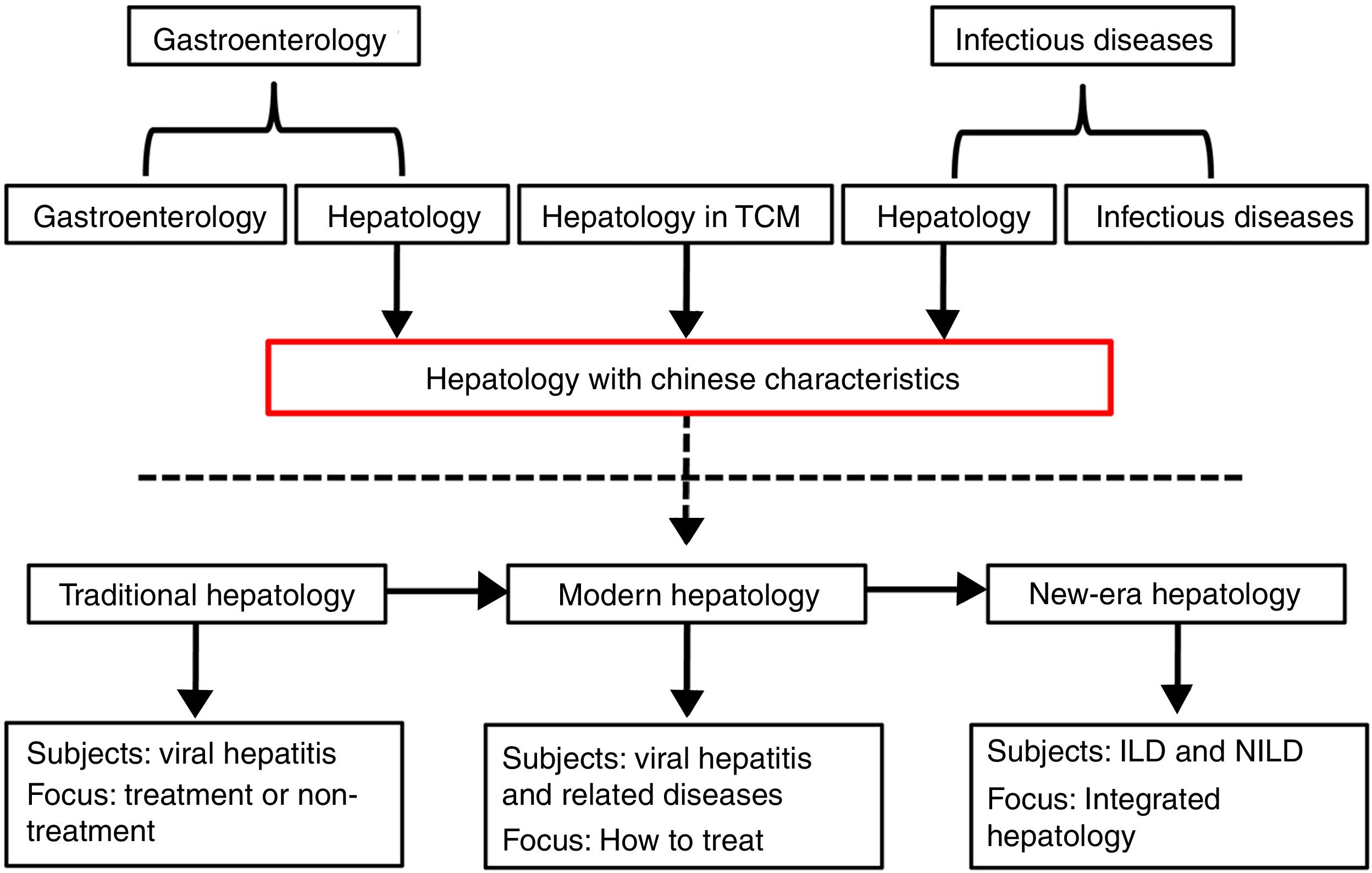

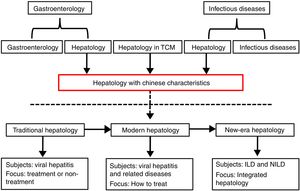

2Development of hepatology in ChinaThe source of hepatology is inconsistent in China. Some are derived from gastroenterology, some are differentiated from the department of infectious diseases, and some are attributed to Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM). Therefore, the focus of the clinician's attention to the patient is also different. As for the historical stage of hepatology, China has evolved from the eras of traditional hepatology and modern hepatology into a new era hepatology. The focus of traditional hepatology is mainly on whether viral hepatitis requires treatment or not. Modern hepatology mainly concerns viral hepatitis and its related problems, and the issue is mainly focused on how to treat them. Currently, non-infectious liver diseases (NILD) become the leading cause of CLD. Other than infectious liver diseases (ILD), liver spectrum of new era hepatology also includes NILD. During this period, the main task of hepatology was to use existing resources to form integrated hepatology (see Fig. 2). Unfortunately, Chinese liver experts lacked a comprehensive training in hepatology, mostly relying on the experience to diagnose and treat liver diseases, which resulting in a disagreement with liver diseases.

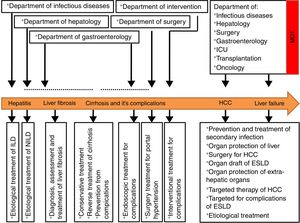

3Current situation on diagnosis and treatment model of CLD in China3.1HepatitisHepatitis often represents an initial stage of development of CLD. Elimination of the cause at this stage can effectively delay or even block the progression and improve the prognosis of CLD. Therefore, the focus of treatment at this stage is to eliminate or control the etiological sources. According to the World Health Organization, there are approximately 240 million patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection worldwide [3]. And 86 million patients with chronic HBV infection lies in China [4]. Patients with viral hepatitis are usually diagnosed and treated by physicians in the department of infectious diseases (formerly known as the department of contagious diseases) in China. As a result, on the one hand, these physicians who are majoring in ILD are busying resolving the viral hepatitis and without times to taking into account of other infectious diseases. Department of infectious diseases is actually became the “department of hepatitis” in some hospitals. On the other hand, physicians who are majoring in non-infectious diseases are not familiar with the discipline scope and related knowledge of liver diseases. As a result, part patients have missed the chances of etiological treatment due to the knowledge absence of their doctors in charge. The same things happened dramatically as the chronic hepatitis C virus infection in China.

With the progression of society, increase in the obese population, abuse of drugs and alcohol and other social factors such as air pollution, the CLD spectrum has gradually shifted from the ILD to the NILD including FLD, ALD, AILD, and other benign liver diseases. In China, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is set to rise from 18% to 29.2% in the past decade and will pose a major health threat in the later decades [5]. The largest DILI population lies in China as a result of TCM, herbal and dietary supplements, and anti-tuberculosis drugs used in China mainland [6]. And ALD poses another severe CLD burden worldwidely [7]. It is worth notable that a combination of chronic viral hepatitis, obesity, drug toxicity, dietary nutritional and alcoholism are not unusual to see in China. However, these NILD appeared most frequently in the departments of internal medicine and infectious diseases, whereas only a small part patient was diagnosed and treated in the department of hepatology.

For the reasons mentioned above, in Chinese hospital, most patients with CLD are concentrated mainly in the department of infectious diseases where over emphasized on ILD and neglected of the NILD. Other clinical departments lack of the understanding for the natural history and harms of NILD. Most patients of NILD were ignored or even lost the chance of etiological treatment or health education due to all the above factors in China. Based on the phenomenon lied in China, physicians including infectious diseases specialists and non-infectious specialists should strength learning about the recognizing of the fundamental etiology and history of the NILD. Government should rising awareness and give more effective health education information to develop a good lifestyle in order to control the pandemic of NAFLD, ALD, DILI and other NILD in China so that all the CLD should be given corresponding treatments according to their different causes.

3.2Liver fibrosisLiver fibrosis is an inevitable reversible pathological repair response in patients with CLD. Timely and effective diagnosis and treatment of patients with liver fibrosis can prevent or delay the progression to cirrhosis or end-stage liver disease (ESLD). However, the liver is a “silent” organ followed by asymptomatic in the early liver fibrosis stage. There has a habit of seeing a doctor till when they have relative symptoms in China. Early evaluation of liver fibrosis is difficult due to lack of special markers of liver fibrosis [8]. Liver biopsy is the “gold standard” for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis, but it is not well accepted by some patients because it may cause trauma and complications. As a result, in clinical practice, liver fibrosis was vastly underestimated, and a delay or missed diagnosis and treatment of early liver fibrosis often happened in China.

The most effective way to prevent the formation of liver fibrosis is by eliminating the stimulus or harmful cause of hepatic damage [9]. It has been proved that in the early stage of liver fibrosis when the cause has been treated, regression occurs in at least 70% of patients [10]; but this is not always feasible in real world [11]. Returning to normal levels of liver biochemical parameters do not indicate that liver tissue inflammation has been cured. Liver histology may still show significant inflammation and progressive fibrosis in some patients with inhibited HBV. So, in addition to etiological treatment, patients at this stage need to be assessed for the degree of fibrosis, clinicians cannot rely solely on liver biochemical profiles for the assessment of liver inflammation and fibrosis. However, physicians in the department of infectious diseases over emphasized antiviral therapy but neglected the treatment of liver fibrosis because without a confirmed pathological diagnosis. At the same time, gastroenterologists diagnose and treat patients until the signs of clinical portal hypertension (such as esophageal varices and ascites) appear. Another aggravating thing is that, except for the lack of noninvasive indicators for early assessment of liver fibrosis, there is little effective anti-fibrotic treatment agents approved to be used.

There is thus an urgent substantial effort for liver disease specialists in China to manage CLD individualized so that treatment timely can be applied in the early stage of liver fibrosis, which will improve the patient prognosis. Instead of the point at which fibrosis becomes irreversible is not yet recognizable. We hope that the burden of cirrhosis will progressively decline by changing our mentality from treating the complications of ESLD into preventing their development at the early liver fibrosis stage.

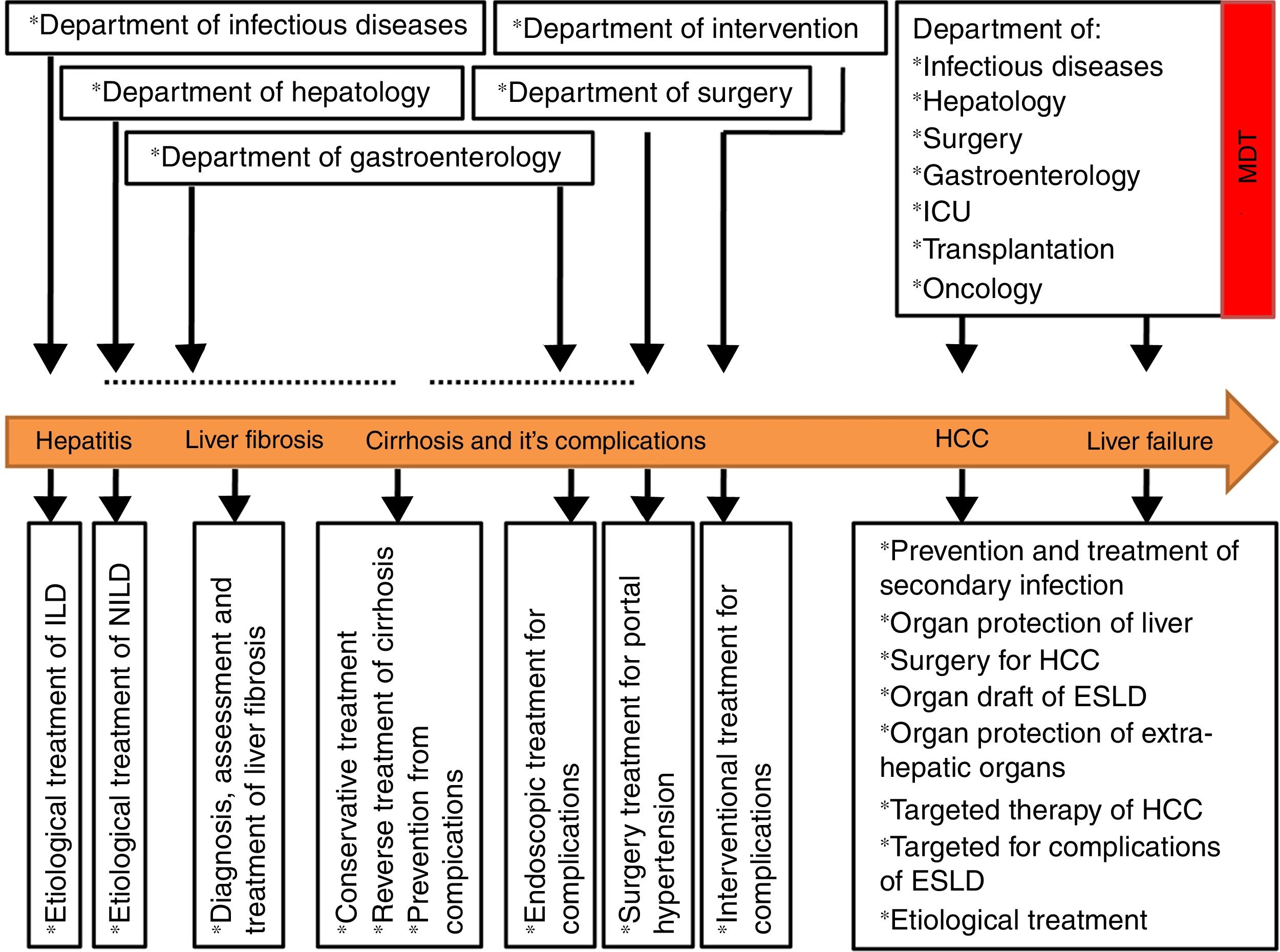

3.3Liver cirrhosisThe essence of cirrhosis is an irreversible progression of liver fibrosis [12]. Early cirrhosis is asymptomatic or present with mild and nonspecific symptoms, and most patients do not realize the real disease condition, especially in these patients in poor rural areas in the Western China. As a result, more and more patients went to see a doctor when the merged of complicating features of cirrhosis involve portal hypertension and even decompensation. A diagnosis of decompensated cirrhosis is associated with a risk of death that is 9.7 times as high as the risk in the general population [13]. The economic burden of cirrhosis in China is focused on the decompensation, including ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), hepatic encephalopathy (HE), variceal hemorrhage, the hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Patients with cirrhosis at this stage are plagued by frequent hospital readmissions for various complications. For patients with early or compensated cirrhosis, in addition to active etiological control (e.g., viral liver disease requires antiviral therapy in the department of infectious diseases, and patients with ALD need to take a liver disease health education in the department of hepatology), long-term and regular follow-up is needed to assess the degree of liver fibrosis to start early intervention to reverse or curb cirrhosis. Patients suspected of progressing to cirrhosis need to undergo endoscopic examination for esophagogastric varices as soon as possible in the department of gastroenterology to identify the degree of the disease and perform treatment timely (such as endoscopic ligation or injection of a sclerosing agent) [14]. For patients with uncontrolled variceal bleeding or those with refractory ascites who poorly respond to conventional drug treatment, a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) may be necessary in the related disciplines [15]. When patients present with HRS including oliguria, anuria and reduced creatinine clearance, liver transplantation may be necessary if conventional medical treatment is ineffective [16]. Most patients at this stage have complications involving multiple organs or systems. Therefore, a multidisciplinary team (MDT) cooperation (including the departments of infectious diseases, hepatology, gastroenterology, endoscopy, interventional medicine, organ transplantation, etc.) is needed at this stage to provide patients with the best therapeutic and improve their quality of life.

The management of cirrhosis must involve prevention and elimination of risk factors, accurate and timely diagnosis, appropriate therapeutic, avoidance of harmful medications and procedures, public education, and care coordination. MDT may be the best way.

3.4Liver failureLiver failure is a clinical syndrome caused by multiple factors and mainly manifests coagulation dysfunction, jaundice, HE, ascites, cerebral edema, acute kidney injury, HRS, gastrointestinal bleeding, severe infection, electrolyte imbalances and hemodynamic disorders [17]. The occurrence and progression of liver failure is a systemic disease. A medical MDT is necessary to fully utilize the advantages of various disciplines to treat these patients. The primary cause of liver failure in China is HBV infection. Therefore, physicians specialized in infectious diseases must first design a strong and low-resistance antiviral regimen and an appropriate antibacterial scheme for the secondary infections. Due to a series of complicated pathophysiological changes in the body when liver failure, in addition to the need for professional liver diseases specialists to develop appropriate liver protective strategies for the specific pathophysiological status, physicians in the department of intensive care unit (ICU), under certain conditions, are needed to protect extra-hepatic organs even in these patients with HE which will be beneficial to the recovery of liver function in patients and allow more time for liver transplantation. When these patients seeking medical treatment due to drugs and hepatotoxic substances. The department of emergency, kidney disease or blood purification center should be involved in the treatment of these patients in China. In addition, nutritional support for patients with ESLD requires participation of nutrition departments [15].

Liver transplantation is the most effective salvage treatment for patients with advanced liver failure and its related complications such as refractory HE and HRS. However, due to the high cost of liver transplantation, lack of donor livers, complications and strict recipient requirements, most patients and physicians believe that liver transplantation is poor accessibility [18]. It is necessary to have close cooperation among all the disciplines and jointly assess the indications for transplantation and add the patient to the wait list. Moreover, effective and targeted treatment should be provided before surgery to help patients to successfully undergo liver transplant surgery with stable conditions throughout the perioperative period.

3.5Hepatocellular carcinomaLiver cancer arose among high-risk populations in low-middle income countries [19]. HCC is one of the most common primary liver malignancies [20]. The median survival time among patients with limited HCC and advanced HCC is approximately 2 years, 6 months, respectively [21]. Therefore, HCC, once called “the king of cancer”, remains a major public health concern [22]. China is a country bearing the largest population of HCC in the world [23]. However, we observed an unfavorable phenomenon that the most patients might be loss the chance of early diagnose when they seeing a doctor and the advanced HCC are common in China. The deeper reasons are worth pondering. Patients with HCC are relatively scattered in every clinical discipline, and it is extremely common for clinicians to treat HCC separately in China.

Currently, the treatment of HCC involves surgery, intervention, local treatment, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, molecular targeted therapy and liver transplantation [22], which are performed in the different departments in China. Regardless of which department the patient is first diagnosed in, the goal of treatment should be to control the tumor progression and prevent recurrence and metastasis [24]. This can allow patients who cannot be cured to live with the tumor for a long time and improve their quality of life. HBV and HCV still are the most important risk factors for HCC in China [25]. So, the etiological treatment is mainly concentrated in the department of infectious diseases who is focused on treatment and research in their specialty and ignored the advantages of other various therapies. Surgeon clinicians tend to focus on the tumor treatment while ignoring the psychological and social aspects of the patient and paying less attention to nursing, nutrition and psychological intervention. This results in separation and dispersion of HCC treatments and reduces the clinical efficacy of the optimal treatment for HCC patients. Apart from HBV and HCV, recent data showed that other factors such as aflatoxin B1, tobacco, obesity, diabetes, alcohol, and NAFLD were also identified as precipitants of liver cancer [26–28]. So, the etiological treatments of HCC should not limited to the department of infectious diseases but involve to other clinical departments such as the departments of hepatology, gastroenterology and surgery.

As for tumors, combined treatments and cooperation can produce better results than a single treatment [29]. Current visiting models and comprehensive treatment models should be changed so as to establish more effective treat strategies.

4TCM in ChinaTCM is frequently used for treating CLD in China [30,31]. However, majority of TCM have only been used experienced. TCM and herbal are the leading causes of DILI in China mainland [6]. The quality of TCM trials must be improved to gather convincing evidence for their use in treating CLD.

5SummaryTaken together, chaotic may be a good description of current status of CLD in China. Since CLD patients with different stages show clinical features or pathophysiological complexity and polymorphisms, the diagnosis and treatment of CLD patients with different stages requires participation of different experts from different disciplines. The diagnosis and treatment strategies of CLD described here can be used to establish a staged-based treatment model for patients with CLD, which is suitable for China's national conditions (see Fig. 3).

Role of the funding sourceThis study was supported by the Chongqing Municipal Health and Family Planning Commission of China (grant number 2016ZDXM038).

Authors’ contributionsJian Xu designed the paper; Xueqin Liu wrote the manuscript.

Data sharingThe corresponding author has the final access to submit the manuscript and data or figures presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

We would like to thank the “American Journal Experts” for edition of the language.