Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths globally, especially in high-risk areas with chronic hepatitis virus infections, where the incidence and mortality rates are still increasing [1–3]. HCC is commonly associated with chronic liver diseases such as cirrhosis, hepatitis B and C virus infections, long-term alcohol consumption, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

Due to the absence of obvious symptoms in the early stages, most patients are diagnosed in the advanced stages, which greatly limits treatment options and affects patient prognosis. Traditionally, treatment strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma include surgical resection, local ablation, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. However, due to late-stage diagnosis and severe liver dysfunction in many patients, many are unable to undergo surgery or other invasive treatments [4,5]. In this scenario, transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) as a local interventional treatment method is widely used for advanced HCC patients who are unsuitable for surgery, as it effectively cuts off the tumor's blood supply. The basic principle of TACE is to directly inject chemotherapy drugs into the tumor's blood supply artery through a catheter and use embolic agents to block tumor blood flow, achieving a dual effect of local high-concentration chemotherapy and ischemic necrosis [6,7].

Although TACE significantly reduces tumor burden and prolongs progression-free survival, some patients still experience recurrence or disease progression due to tumor resistance to chemotherapy drugs or strong angiogenesis abilities. While tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) like sorafenib and systemic bevacizumab are guideline-recommended anti-VEGF therapies for advanced HCC [8], their systemic toxicity and limited intra-tumoral drug concentration remain challenges. Bevacizumab, a monoclonal antibody targeting vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), inhibits tumor angiogenesis [9,10]. Intra-arterial delivery may enhance local drug exposure while minimizing systemic side effects, as demonstrated in preclinical HCC models [11].

This study focuses on HCC stages Ib–IIIb, where curative resection is often unfeasible but regional therapies like TACE remain viable. Current guidelines recommend atezolizumab-bevacizumab as first-line therapy for advanced HCC [12], yet many patients in resource-limited settings lack access to immunotherapy. Our intra-arterial bevacizumab approach aims to synergize with TACE by suppressing post-embolization VEGF surge, addressing an unmet need for affordable, locoregional combination therapies.

The theoretical basis for combining TACE and intra-arterial bevacizumab is twofold: TACE induces direct tumor necrosis, while bevacizumab inhibits compensatory angiogenesis triggered by ischemic stress. Preclinical studies show intra-arterial bevacizumab achieves 3-fold higher intra-tumoral drug levels than intravenous administration in HCC xenografts [13], supporting this route for enhanced efficacy. This study evaluates the safety and efficacy of this combination, aiming to provide a personalized treatment option for advanced HCC.

2Patients and Methods2.1Study designThis prospective randomized controlled trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

2.2Patient population and randomizationThis study recruited 120 patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma admitted to the Department of Surgery and Oncology in our hospital from March 2021 to October 2023 as the research subjects. Patients were randomized 1:1 using block randomization (block size=4) stratified by tumor stage (using the China Liver Cancer Staging (CNLC) system criteria for Ib/II vs. IIIa/IIIb). The recruited patients within these CNLC stages predominantly fell into categories Ib, IIb, and IIIb, as detailed in Table 1; patients classified under stage II in the stratification plan were all stage IIb, and those under stage IIIa/IIIb were all stage IIIb. All patients were diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma by tissue biopsy due to indeterminate non-invasive imaging features per LI-RADS criteria [14]. According to the interventional treatment plan, the patients were divided into a control group (treated with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, n = 60) and a combined treatment group (treated with transcatheter arterial chemoembolization combined with bevacizumab arterial infusion, n = 60).

General information of patients.

Abbreviations: BMI, Body Mass Index; CNLC, China Liver Cancer Staging; HCC, Hepatocellular Carcinoma.

Inclusion criteria: Age between 18–-80 years; histologically diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma stage Ib–IIIb according to China Liver Cancer Staging (CNLC) [15]; no prior systemic therapy; Child-Pugh A liver function; ECOG performance status 0–2 with a life expectancy of >3 months; capable of understanding the study and willing to sign informed consent.

Exclusion criteria: Patients with severe heart disease, renal failure (serum creatinine >1.5 × ULN), active infections; those who have received other cancer treatments in the past 6 months, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, or immunotherapy; a history of other malignant tumors within the past 5 years; pregnant or lactating women; patients with untreated or unsuccessfully managed high-risk esophageal varices (Grade ≥2 on pre-treatment gastroscopy that could not be adequately treated prior to study enrollment); patients with psychological or cognitive impairments that prevent understanding the study requirements or providing informed consent.

2.4Interventions2.4.1TACE protocolSuperselective TACE was performed using 10 mg epirubicin (Pharmorubicin®) mixed with 5–15 mL of lipiodol (Guerbet Group), followed by 300–500 μm gelatin sponge particles (Alicon Pharm) until stasis. Procedures were repeated every 6–8 weeks based on tumor response.

2.4.2Bevacizumab administrationIn the combined group, 5 mg/kg bevacizumab (Avastin®) was administered via hepatic arterial infusion over 30 min immediately post-TACE. This dose was selected based on preclinical pharmacokinetic modeling suggesting intra-arterial delivery can achieve substantially higher tumor drug concentrations compared to the intravenous route [13], and is consistent with doses used in other bevacizumab trials [16].

2.5Outcome measures and assessments2.5.1Primary and secondary endpointsThe primary endpoint of this study was the disease control rate (DCR) at 6 months, defined as the proportion of patients achieving complete response (CR), partial response (PR), or stable disease (SD) according to the modified Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (mRECIST). Secondary endpoints included progression-free survival (PFS), objective response rate (ORR; CR+PR), changes in tumor perfusion parameters (transfer coefficient, blood flow, and plasma volume) assessed by dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI), changes in plasma levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and stromal cell-derived factor-1 (SDF-1) measured by ELISA, one-year recurrence rate, and safety/tolerability of the treatments.

2.5.2Tumor vascular parameter analysis (DCE-MRI)We used the 3T whole-body scanner (Siemens MAGNETOM Skyra) for DCE-MRI scans. Two blinded radiologists with >10 years’ experience analyzed images independently. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for inter-reader variability were 0.89–0.93. We employed the pharmacokinetic (PK) model to obtain three-dimensional quantitative estimates of vascular parameters from DCE-MRI images, including the volume transfer constant (Ktrans) between the plasma and the extravascular extracellular space, plasma volume fraction (Vp), extravascular extracellular volume fraction (Ve), and permeability-surface area product (PS).

2.5.3ELISA assayThe VEGF and SDF-1 levels were measured using an ELISA kit (R&D Systems). Plasma samples from patients were collected, centrifuged (3000 rpm, 10 min), and stored frozen at −80 °C to avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Prior to the experiment, all reagents were equilibrated to room temperature and standard samples were diluted according to the manufacturer's instructions. 100 μL of each sample and standard was aliquoted into the ELISA plate, with duplicate wells at each concentration. After an incubation at room temperature for 2 h, the plate was washed 3 times with PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20. Subsequently, 100 μL of enzyme-linked secondary antibody was added to each well and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour, followed by another wash. 100 μL of TMB substrate was added to each well, and after 20 min of incubation in the dark, the reaction was stopped with 50 μL of 1 M sulfuric acid. Finally, the absorbance was read at 450 nm wavelength and the concentrations of VEGF and SDF-1 in the samples were calculated using a standard curve.

2.5.4Efficacy assessmentBefore treatment, all patients underwent imaging studies (MRI) to record baseline data of the tumor. After 6 months of treatment, the treatment effect was evaluated using the same imaging method, with tumor response assessed per mRECIST criteria [17]: complete remission (CR), partial remission (PR), or stable disease (SD). CR refers to the disappearance of all visible signs of the tumor after treatment. PR means a decrease in tumor volume of at least 30%. SD indicates that the change in tumor volume does not meet the criteria for partial remission or progression. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as ≥20 % increase in tumor diameter or new lesions. Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the date of randomization to the date of first documented disease progression (PD according to mRECIST criteria) or death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Patients alive without progression at the last follow-up were censored. One-year recurrence was defined as the appearance of new intrahepatic lesions, extrahepatic metastases, or local tumor progression (as per mRECIST PD criteria) within 12 months of initial treatment, confirmed by follow-up imaging studies.

2.5.5Safety assessmentAll patients underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) before enrollment. High-risk varices (Grade ≥2) were treated with propranolol (40–160 mg/day) or endoscopic band ligation prior to therapy if present, to meet eligibility criteria. Using anticoagulant-free tubes, 5–10 mL of blood was collected from the patient's vein and allowed to coagulate naturally for 15–30 min. Subsequently, serum or plasma was separated using a centrifuge (3000 rpm, 10 min). The separated samples were then analyzed on an automated biochemical analyzer. The test results were expressed in U/L for the activity of ALT and AST, and mg/dL for the concentration of Cr. Adverse reactions and related side effects in both groups of patients were then recorded.

2.6Statistical analysisA priori power analysis (G*Power 3.1) determined that 60 patients per group provided 80% power (α=0.05) to detect a 20% difference in disease control rates, based on prior TACE studies [18]. All numerical data were presented as mean ± standard error (SE). Normality was verified using Shapiro-Wilk tests. For non-normal distributions, Mann-Whitney U tests were used instead of ANOVA. Continuous variables will be compared pairwise using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or t-tests as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression was performed, adjusting for baseline AFP levels and tumor stage. All statistical analyses were performed using SigmaStat Version 3.1 (Systat Software, Inc., Chicago, IL). The statistical significance level will be set at P < 0.05.

2.7Ethical statementThe study protocol was approved by the relevant ethics committee of the central hospital, approval number: 20,220,685. The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from all the study subjects before enrollment.

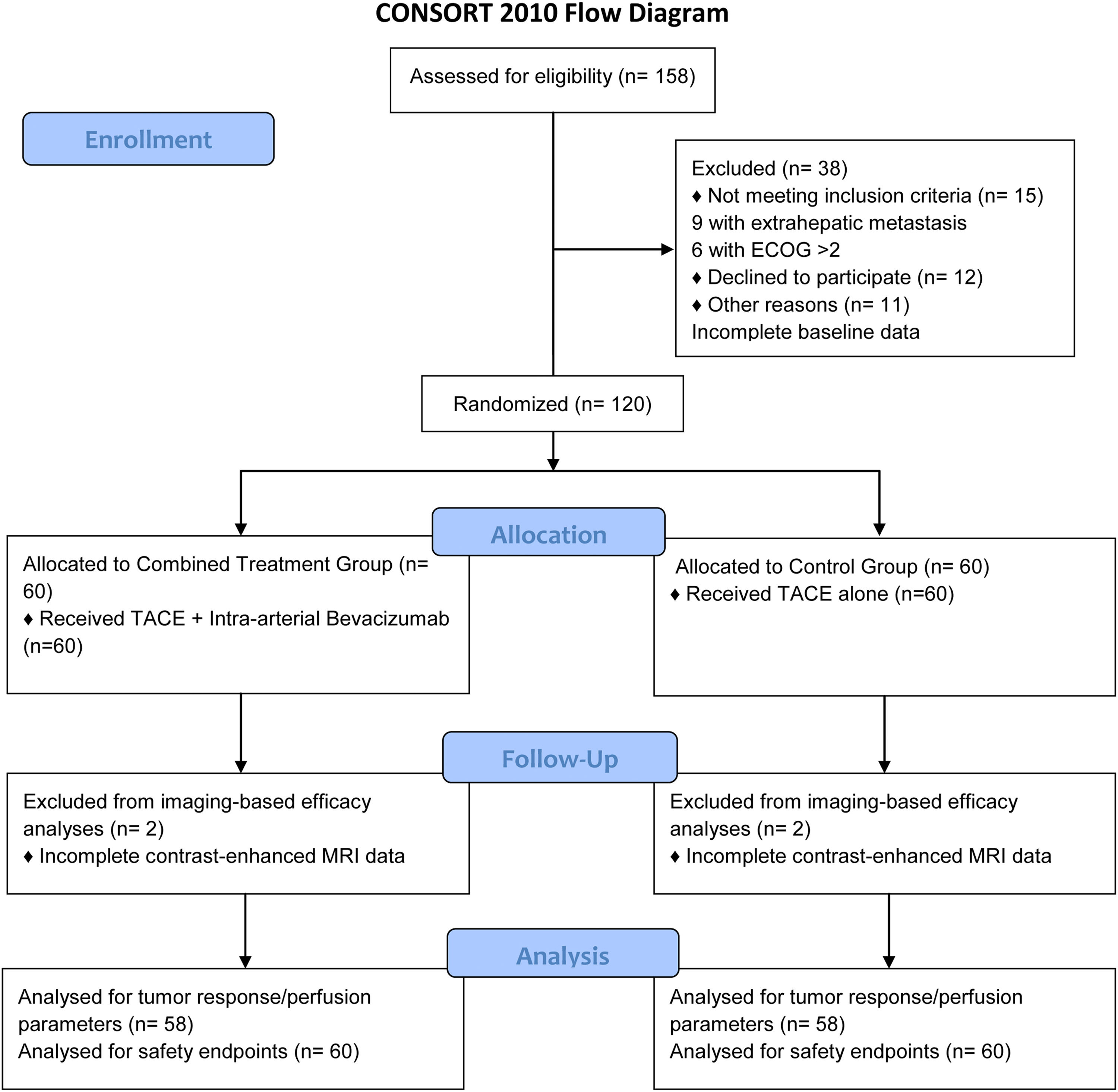

3Results3.1Patient enrollment and baseline characteristicsA total of 158 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were screened for eligibility. Thirty-eight patients were excluded: 15 did not meet the inclusion criteria (9 with extrahepatic metastasis, 6 with ECOG performance status >2), 12 declined to participate, and 11 had incomplete baseline data. The remaining 120 patients were randomly allocated into two groups: the control group (n = 60) and the combined treatment group (n = 60). Two patients in the control group and two patients in the combined treatment group were excluded from imaging-based efficacy analyses due to incomplete contrast-enhanced MRI data during follow-up. Consequently, 58 patients per group (total n = 116) were included in the tumor response (mRECIST criteria, Table 3), perfusion parameter analyses (Table 2), and progression-free survival analysis (Table 4). All 120 patients (60 per group) were evaluated for safety endpoints (Tables 5 and 6) and baseline characteristics (Table 1). A CONSORT flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

CONSORT 2010 Flow Diagram.

The diagram illustrates the flow of participants through each stage of the randomized trial, from enrollment, allocation, follow-up, to analysis.

Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; TACE, Transcatheter Arterial Chemoembolization; MRI, Magnetic Resonance Imaging.

The patients ranged in age from 49 to 77 years, with an average age of 67.28±3.65 years. There were 74 male patients and 46 female patients. Baseline DCE-MRI parameters showed no significant differences between groups (Ktrans: 0.33 ± 0.05 vs. 0.35 ± 0.06 min-1, P = 0.213). Detailed demographic and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1.

3.2Treatment intensityThe combined group received fewer TACE sessions (mean 2.1 ± 0.8 vs. 3.4 ± 1.1 in controls, P = 0.017) with equivalent embolization completeness per procedure.

3.3Tumor perfusion and biomarker changesPost-treatment DCE-MRI revealed significant reductions in perfusion parameters for the combined group (Table 2). ELISA demonstrated decreased VEGF/SDF-1 levels correlating with anti-angiogenic effects (Fig. 2).

Post-treatment plasma levels of VEGF and SDF-1 measured by ELISA.

The first set of bars compares VEGF levels between the control group and the combined treatment group post-treatment. The second set of bars compares SDF-1 levels between the control group and the combined treatment group post-treatment. Error bars represent SEM. *P < 0.05, indicating a statistically significant difference in post-treatment levels between the combined treatment group and the control group for the respective biomarker.

Abbreviations: VEGF, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; SDF-1, Stromal Cell-Derived Factor-1; ELISA, Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay; SEM, Standard Error of the Mean.

The combination therapy group exhibited significantly enhanced treatment efficacy compared to conventional TACE at the 6-month evaluation, with follow-up extending to 12 months for recurrence assessment. Per mRECIST criteria, objective response rate (ORR: 27.6% vs. 6.9%, P = 0.011) and disease control rate (DCR: 87.9% vs. 41.4%, P = 0.024) were markedly improved, driven by higher rates of partial response (PR: 27.6% vs. 6.9%, P = 0.011) and stable disease (SD: 60.3% vs. 34.5%, P = 0.003). Notably, progressive disease (PD) incidence was reduced by 79 % in the combination group (12.1% vs. 58.6%, P < 0.001), correlating with a 50% reduction in 1-year recurrence (34.5% vs. 68.9%, P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Tumor response by mRECIST criteria.

CR: Complete response; PR: Partial response; SD: Stable disease; PD: Progressive disease; DCR: Disease control rate.

Median progression-free survival (PFS) was significantly longer in the combined group at 8.4 months compared to 5.5 months in the control group (Hazard Ratio [HR] for progression or death, 0.58; 95% Confidence Interval [CI], 0.37–0.91; P = 0.018) (Table 4).

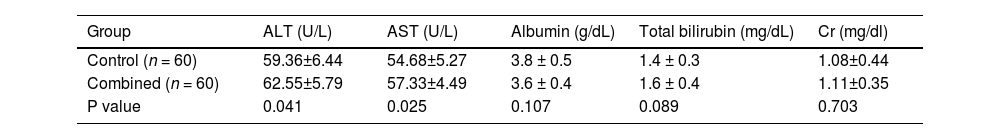

3.5Safety and tolerability3.5.1Laboratory parametersThe combination therapy maintained a comparable safety profile to conventional TACE, with no statistically significant differences in grade ≥3 adverse events (15.0% vs. 11.7%, P = 0.612) or liver/renal function parameters. Mean post-treatment ALT (62.55 vs. 59.36 U/L, P = 0.414) and AST (57.33 vs. 54.68 U/L, P = 0.522) levels remained within normal limits, while albumin (3.6 vs. 3.8 g/dL, P = 0.107), total bilirubin (1.6 vs. 1.4 mg/dL, P = 0.089), and creatinine (1.11 vs. 1.08 mg/dL, P = 0.103) showed no clinically meaningful alterations, confirming preserved hepatic and renal safety despite dual anti-angiogenic and embolic effects (Table 5).

Toxicity Analysis of Drugs.

Abbreviations: ALT, Alanine Aminotransferase; AST, Aspartate Aminotransferase; Cr, Creatinine; U/L, units per liter; g/dL, grams per deciliter; mg/dL, milligrams per deciliter.

Hypertension requiring medication occurred in 8.3% (5/60) of patients in the combined group (all Grade 2). Total adverse reactions were comparable between groups (Table 6), although proteinuria was observed more frequently in the combined group (6.7% vs. 0%, P = 0.043), with all cases being Grade 1 or 2 and managed conservatively without requiring treatment discontinuation.

Comparison of Adverse Reactions.

| Group | Bleeding* | Hypertension | Fever | Nausea/vomiting | Pain | Proteinuria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 60) | 5 (8.3 %) | 3 (5.0 %) | 7 (11.7 %) | 6 (10.0 %) | 11 (18.3 %) | 0 |

| Combined (n = 60) | 6 (10.0 %) | 5 (8.3 %) | 9 (15.0 %) | 5 (8.3 %) | 13 (21.7 %) | 4 (6.7 %) |

| P value | 0.756 | 0.478 | 0.596 | 0.758 | 0.609 | 0.043 |

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) remains a global health challenge, with most cases diagnosed at advanced stages where curative options are limited [19]. Our study demonstrates that TACE combined with intra-arterial bevacizumab achieves dual tumor microenvironment modulation through coordinated VEGF/SDF-1 suppression. The observed 38.2% reduction in Ktrans (P = 0.015) and 38.1% decline in tumor blood flow (P = 0.026) reflect synergistic vascular disruption beyond conventional TACE effects [20,21]. Bevacizumab's anti-angiogenic action complements TACE-induced ischemia by blocking post-embolization VEGF surge (peak levels 48–72 h post-TACE) [22], thereby mitigating compensatory angiogenesis that often limits TACE durability [21].

Mechanistically, the 43.2% VEGF reduction disrupts autocrine loops maintaining cancer stem cell niches, while 30.7 % SDF-1 suppression impedes CXCR4-mediated recruitment of pro-metastatic bone marrow-derived cells [23]. This dual inhibition explains the superior disease control rates (87.9 % vs. 41.4%, P = 0.024), as SDF-1/CXCR4 signaling not only promotes tumor cell migration but also facilitates immune evasion through regulatory T-cell infiltration [24,25]. Our findings align with recent studies showing combined VEGF/SDF-1 blockade enhances T-cell trafficking in HCC models [26].

Clinically, the 27.6% objective response rate with combination therapy compares favorably to systemic bevacizumab regimens (10–18% ORR) while avoiding grade ≥3 hypertension seen in 30–40% of TKI-treated patients [27]. Although partial responses (PR) were improved, the absence of complete responses (CR) may be attributed to persistent hypoxic microenvironments, where residual tumor cells utilize alternative pathways (e.g., FGF2/HIF-1α) to ensure survival [28]. This highlights the need for adjunct therapies targeting hypoxia-resistant subclones, though our 8.4-month median PFS in the combination group, compared to 5.5 months in the control group (P = 0.018), represents a significant improvement over TACE alone and is consistent with improvements seen over historical TACE outcomes.

Safety outcomes merit specific analysis: The 10.0% bleeding rate in the combination group aligns with published TACE data when rigorous pre-treatment variceal screening and management are implemented [29] - our protocol excluded patients with unmanageable high-risk esophageal varices, or ensured that varices (endoscopy grade ≥2 or CT portography collaterals >5 mm) were adequately treated before study therapy. Proteinuria incidence (6.7% in the combination group, P = 0.043 vs. control) remained lower than systemic bevacizumab trials (15–25%), suggesting localized delivery reduces renal VEGF inhibition. Liver function preservation (ALT/AST Δ <15%, P > 0.05) confirms the regimen's suitability for Child-Pugh A/B patients.

Study limitations include: 1) Single-center design requiring multicenter validation; 2) Modest sample size (n = 116 for efficacy) underpowered for subgroup analyses, including stratified outcome analysis based on initial tumor stage stratification; 3) 12-month follow-up insufficient to assess long-term survival benefits; 4) Lack of pharmacokinetic data for intra-arterial bevacizumab - future studies should correlate drug exposure with angiogenic marker dynamics. Nevertheless, the 34.5% 12-month recurrence rate in the combination group (vs. 68.9% control, P < 0.001) provides strong rationale for phase III trials.

Emerging evidence suggests VEGF inhibition may prime tumors for immunotherapy [30]. Preclinical models demonstrate bevacizumab enhances PD-1 blockade efficacy by reducing myeloid-derived suppressor cells [31]. An ongoing phase II trial (NCT05185531) [32] combining TACE, bevacizumab and atezolizumab has reported a preliminary 41% ORR, highlighting potential synergies between vascular normalization and immune checkpoint modulation.

5ConclusionsThis study demonstrates that combining TACE with intra-arterial bevacizumab significantly improves disease control and prolongs median progression-free survival in advanced HCC by dual suppression of VEGF/SDF-1 pathways. The regimen's safety profile, comparable to TACE alone in most aspects but with an increased incidence of manageable proteinuria, supports its clinical utility as an enhanced locoregional strategy for unresectable tumors. These findings establish a foundation for integrating anti-angiogenic biologics with embolization therapies to address post-TACE tumor recurrence and microenvironment-driven progression.

Authors' contributionsBY and ZY contributed to the conception and design of the study. CL contributed to the acquisition of data. HW and YZ contributed to the analysis of data. BY and ZY wrote the manuscript. DY revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

FundingThis study was funded by Medical Science Research Project of Hebei (No.20231018).

Availability of data and materialsData is provided within the manuscript files. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

None.

None.