Editado por: Dra. Núria Torner CIBER Epidemiologia y Salud Publica CIBERESP Unitat de Medicina Preventiva i Salut Pública Departament de Medicina, Universitat de Barcelona

Más datosA new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), causing COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), is a member of the Coronaviridae family. The benefits of the primary COVID-19 vaccination far outweigh the risks. Nevertheless, the risks associated with too early and too frequent boosters should be considered, especially when vaccines have immune-mediated effects like myocarditis, which is more commonly associated with the second dose of some mRNA vaccines. Booster vaccinations against SARS-CoV-2 are needed because of either reduced immunity to the original vaccine or evolved viruses producing immunity to the initial vaccine antigens. So, the aim of this study was to detect the difference in neutralizing anti-RBD antibodies between the third and second doses of COVID-19 vaccines. A study was performed among 29 eligible participants in Birjand (Iran). Blood samples were taken from all participants 2–4 weeks after the third dose. In the next step, humoral responses were assessed with a kit detecting neutralization of SARS-CoV-2. SPSS software version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used to analyze the data. The mean age of cases was 35.62±8.72 years, with a range of 21–53 years. The obtained results showed that all vaccines significantly had a higher efficacy in the third dose than the second. Participants who received Vaxzevria in the second dose and PastoCovac Plus in the third dose had more immunogenicity. According to the results of this study, a third dose of the vaccine should be given to persons aged ≥20 years to provide an increased level of protection against COVID-19. Especially, participants who received Sputnik-V and Vaxzevria in the second dose and PastoCovac Plus in the third dose showed a more effective immune response against the virus.

Un nuevo coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), causante de la COVID-19 (enfermedad por coronavirus de 2019), se ha unido a la familia Coronaviridae. Los beneficios de la vacunación contra la COVID-19 primaria superaron con creces los riesgos. Sin embargo, deberán considerarse los riesgos asociados a los refuerzos demasiado tempranos y frecuentes, y en especial cuando las vacunas tienen efectos inmunomediados tales como la miocarditis, que está más comúnmente asociada a la segunda dosis de algunas vacunas ARNm. Las vacunas de refuerzo contra la SARS-CoV-2 son necesarias, debido a la inmunidad reducida de la vacuna original, o bien a la evolución de los virus que producen inmunidad frente a los antígenos de la vacuna inicial. Por ello, el objetivo de este estudio fue detectar la diferencia en términos de neutralización de los anticuerpos anti-RBD entre la tercera y segunda dosis de las vacunas frente a la COVID-19. Se realizó un estudio con 29 participantes elegibles en Birjand (Irán). Se tomaron muestras de sangre de todos los participantes, transcurridas de 2 a 4 semanas de la tercera dosis. En la siguiente etapa se evaluaron las respuestas humorales con un kit para detectar la neutralización de SARS-CoV-2. Se utilizó el software SPSS versión 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, EEUU) para analizar los datos. La edad media de los casos fue de 35,62 ± 8,72 años, con rango de 21 a 53 años. Los resultados obtenidos reflejaron que todas las vacunas tenían una eficacia significativamente mayor en la tercera dosis, en comparación con la segunda. Los participantes que recibieron Vaxzevria en la segunda dosis, y PastoCovac Plus en la tercera, tuvieron mayor inmunogenicidad. De acuerdo con los resultados de este estudio, deberá administrarse una dosis de la vacuna a las personas ≥20 años, para aportar un nivel incrementado de protección frente a la COVID-19. En especial, los participantes que recibieron Sputnik-V y Vaxzevria en la segunda dosis, y PastoCovac Plus en la tercera, reflejaron una respuesta inmunitaria más efectiva frente al virus.

A new coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), causing COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019), is a member of the family Coronaviridae. Also, this family includes severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronaviruses,1 which contain several non-structural and structural proteins encoded by their genomes, including spike (S), nucleocapsid (N), membrane (M), and envelope (E).2 COVID-19 vaccine candidates are conceptualized with the aim of administering viral antigens or viral gene sequences to stimulate neutralizing antibodies against the viral spike protein (S), followed by blocking virus uptake by the ACE2 receptor.3 In the battle against SARS-CoV-2 infection, a vaccine-development effort with unprecedented speed began on January 11, 2020, in response to the availability of the genome sequence.4 Despite all this, new COVID-19 cases caused by the highly transmissible delta variant have exacerbated the public health crisis worldwide, raising the question about the need and timing of the administration of booster doses for vaccinated populations.5 Although it is appealing to increase immunity among COVID-19 vaccine recipients to reduce the number of infected cases, any such decision should be evidence-based and weigh both the risks and benefits for individuals and society. Needless to say, COVID-19 vaccines still have significant effectiveness against severe variants, including delta 1.6 Due to the potential confounding and selective reports, most observational studies supporting this conclusion are preliminary and challenging to precisely interpret the results. Therefore, a systematic and public examination of the evolving data would be required to decide about boosting based on reliable science rather than merely political considerations. However, the booster doses could still decrease the medium-term risk of severe disease in the case of having a beneficial long-term effect on unvaccinated populations rather than already vaccinated people.7 Individuals who received a one- or two-dose series of each vaccine for the primary vaccination might not have received adequate protection, such as those who received vaccines with low efficacy or those who are immunocompromised.8 Apart from that, an additional dose of the same vaccine or a different vaccine that may complement the primary immune response would be more beneficial to immunocompromised individuals.9 In the general population, booster vaccinations are sometimes needed due to either reduced immunity to the original vaccine or the insufficient immune response of original vaccine antigens against circulating evolved viruses.10

Clearly, the benefits of the primary COVID-19 vaccination far outweigh the risks. Nevertheless, the risks associated with too early and too frequent boosters should be considered, especially when vaccines have immune-mediated effects like myocarditis, which is more commonly associated with the second dose of some mRNA vaccines.11 Since a significant adverse reaction caused by unnecessary boosters may affect COVID-19 vaccine acceptance, widespread boosting should only be undertaken when needed.12 Randomized trial studies have consistently demonstrated the high initial efficacy of several vaccines.13 In contrast, observational studies have shown a lower initial efficacy and/or a less-durable efficacy of vaccines.14 This study aimed to detect the difference between neutralizing anti-RBD immunoglobulin G between a third and second dose of various vaccine platforms.

Materials and methodsDesign of studyIn our recent study conducted from May to August 2021, individuals associated with Birjand University of Medical Sciences, Birjand, Iran comprising healthcare workers, students, and administrative staff, who expressed interest in receiving the COVID-19 vaccine were invited to participate. Participants were required to provide 5 ml of venous blood before receiving the first dose of the vaccine and 2 weeks after the second dose. Additionally, participants were asked to complete an online questionnaire covering demographic data, history of previous COVID-19 infection, and details about the date and type of received vaccines.15 In the following our previous research, this study has been done among eligible cases who had received the third dose of vaccine in the last 2–4 weeks. In this study (the interval between the second dose and the booster dose was 4–6 month), 30 people were selected who participated in the previous study included those who desired to take the COVID-19 vaccine, such as students, employees, and administrative staff. The inclusion criteria for this study were injections of third doses of one of the vaccines Vaxzevria, Covilo, and PastoCovac Plus and participated in our previous study. Exclusion criteria were: unwillingness to donate blood on time, and positive COVID-19 test during the study period. Then, 5 ml of venous blood were collected from each participant 2 weeks after receiving the third dose of vaccine (Vaxzevria, Covilo, and PastoCovac Plus) To separate the serum, the samples were centrifuged at 2000 rpm for 10 min and then stored at −20 °C until further analysis. Then, to evaluate the level of anti-SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibodies, a commercial IgG antibody detection kit against SARS-CoV-2 RBD (ChemoBind®) was used. This kit can detect RBD-ACE2 reaction inhibitory antibodies by indirect ELISA. Thus, the plate wells were coated with RBD antigen (spike S). Finally, based on indirect ELISA and light absorption for each sample, the immunological status ratio (ISR) was measured and based on the ISR value, the samples were divided into 3 categories: positive (ISR ≥1.1), negative (ISR ≤0.8), and the need for re-testing (0.8–1.1).

Ethical approvalThe Ethics Committee of the Birjand University of Medical University approved this study (IR.BUMS.REC.1400.027). The informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Statistical analysisSPSS software version 22.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL) was used to analyze the data. Statistical analysis was done using Student's t-test and Chi-square tests at a significance value of p<.05. Analysis of more than 2 groups was completed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey's post-hoc test with a p<.05.

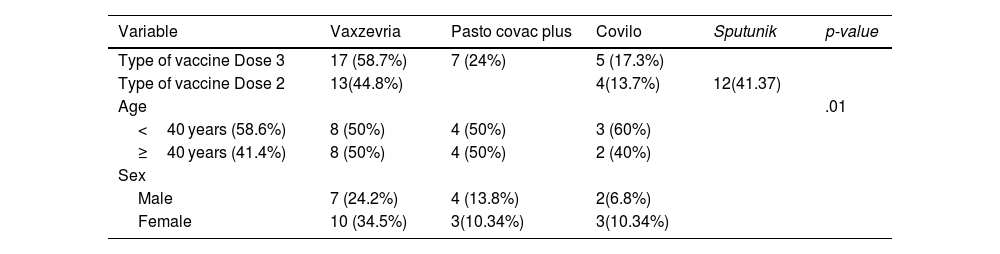

ResultsDemographic characteristicsIn total, 30 participants were included (mean age of 35.62±8.72 years, range of 21–53 years, Male/Female ratio:). Details of the demographic information and type of vaccines were summarized in (Table 1).

A statistical analysis of the demographic characteristics of vaccine recipients.

| Variable | Vaxzevria | Pasto covac plus | Covilo | Sputunik | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of vaccine Dose 3 | 17 (58.7%) | 7 (24%) | 5 (17.3%) | ||

| Type of vaccine Dose 2 | 13(44.8%) | 4(13.7%) | 12(41.37) | ||

| Age | .01 | ||||

| <40 years (58.6%) | 8 (50%) | 4 (50%) | 3 (60%) | ||

| ≥40 years (41.4%) | 8 (50%) | 4 (50%) | 2 (40%) | ||

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 7 (24.2%) | 4 (13.8%) | 2(6.8%) | ||

| Female | 10 (34.5%) | 3(10.34%) | 3(10.34%) |

*One-way ANOVA was used at a significance level of <.05.

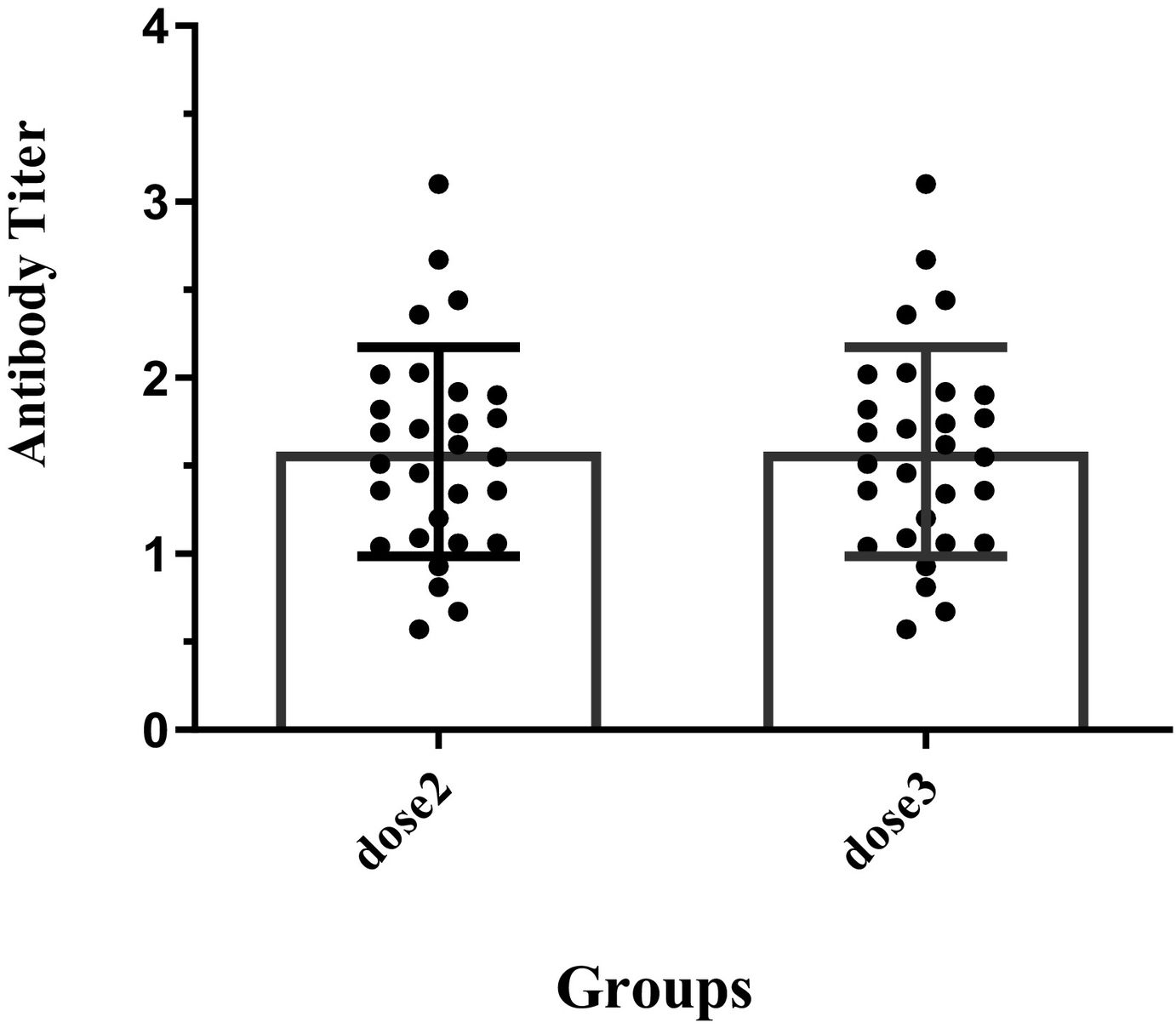

The positive frequency of RBD protein antibody 2 weeks after the third dose of vaccines is shown in Fig. 1. As it is demonstrated in Fig. 2, all vaccines showed significantly higher efficacy in the third dose than in the second dose. A comparison of vaccine efficacy showed that there was significant difference in immunogenicity between the 2 doses; however, participants who received Vaxzevria and PastoCovac Plus in the third dose significantly had a better immunogenicity than the second dose, participants who received Vaxzevria in second dose and PastoCovac Plus in third dose had more immunogenicity (p<.05) (Fig. 2).

The comparison of vaccine efficacy in different platforms after second and third dose. The data are reported as the mean±SD of at least 3 independent experiments. * indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the sputnik V d2 group and Pas d3.* indicates a statistically significant difference compared to the vaxzevria group and Pas d3.

At present, vaccination provides the best protection against COVID-19 infection. Observations indicate that humoral immunity against SARS-CoV-2 infection appears to be reduced in the months after vaccination, especially in the elderly and those with immunosuppression.16–18 In the present study, the efficacy between the second and third dose of Vaxzevria A, Covilo, and PastoCovac Plus was studied in people with the age of 21–53 years who received the vaccine 2–4 weeks after the second dose. In accordance with others, the results of the current research showed that titers of neutralization geometric mean against the covid increased after a booster dose administered approximately 2–4 weeks after the second dose, Therefore, the greatest effectiveness of the vaccine is observed after 2–4 weeks after the injection of the booster dose of the vaccine.9 COVID-19 booster vaccinations have been implemented in some countries based on the above-mentioned data as well as immunological and safety results from the pivotal trials.19,20 According to our results, PastoCovac Plus vaccines are more effective than Covilo and Vaxzevria vaccines in the third dose probably because of different vaccines platforms.17 In a more detail, live viral carriers are used in the Vaxzevria vaccines platform.21 While, in the Covilo’s vaccine inactive viruses are applied that have a minor effects on the immune system.22 Also, PastoCovac Plus is a conjugate vaccine. Studies showed that Vaxzevria and Sputnik V vaccines could produce about 90% immunogenicity 30.31. According to most studies, the effectiveness of Covilo vaccines is near 70%.23 Although, no studies are available about the efficacy of the PastoCovac Plus vaccine, according to our data, participants who received Vaxzevria in the second dose and PastoCovac Plus in the third dose showed the higher titers of antibodies. Our data showed that a booster dose administered approximately 2–4 weeks after the third dose increased the geometric mean titers against the delta variant. The pivotal trial results and immunological and safety findings for a booster dose have led to some countries conducting booster vaccinations with COVID-19. Based, it is crucial to use published data from prospective and randomized trials regarding booster doses’ safety, immunogenicity, and effectiveness as soon as possible.24

Regarding the effectiveness of boosters in real-world situations, a trial involving elderly Israeli adults showed that the third dose of BNT162b2 vaccine administered at least 5 months after the second dose resulted in a lower incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe form of the COVID-19.19 Similar to our findings, several studies from the UK, Germany, and Spain showed that injection various vaccine platforms resulted in a higher antibody response than receiving 2 doses of the viral vector vaccine. To “boost” the immune system, administration of an Oxford-Vaxzevria viral vector vaccine and then a Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccine could better stimulate different parts of the immune system, resulting in a more robust immune response than a viral vector vaccine alone. According to the results of this study, a third dose of the vaccine should be given to persons aged ≥20 years to provide an increased level of protection against COVID-19. Especially, participants who received a Sputnik-V and Vaxzevria in the second dose and PastoCovac Plus in the third dose showed a more effective immune response against the virus.

Author contributionsStudy concept and design: A.M.

Acquisition of data: M. R.

Analysis and interpretation of data: S. A. E.

Drafting of the manuscript: S.N.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: A.M.

Statistical analysis: A.F.

Administrative, technical, and material support: M.F

EthicsAll ethical standards approved by the ethics committee of the Birjand University of Medical Sciences (IR. bums.1401.162)

FundingThis work was supported by Birjand University of medical sciences (5878).

This work was financially supported by Birjand University of Medical Sciences. Birjand. Iran.