Cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis (CNGM) is a rare and underrecognized subtype of granulomatous mastitis, increasingly associated with Corynebacterium species, particularly Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii. Despite a growing number of reports, its diagnosis remains challenging, and treatment approaches are highly variable.

This systematic review aimed to consolidate the clinical, microbiological, and therapeutic characteristics of CNGM to better inform clinical management. A structured search of PubMed using MeSH terms identified 13 studies, of which 11 met inclusion criteria.

These studies, encompassing 387 patients, were analyzed for clinical presentation, diagnostic methods, histopathological findings, bacterial species, antimicrobial susceptibility, treatment strategies, and outcomes. CNGM typically presented as a unilateral painful breast mass, frequently accompanied by abscess, nipple inversion, or fistulae. Diagnosis was established via histopathology and confirmed by microbiological testing, often through MALDI-TOFMS or 16S rRNA sequencing. While C. kroppenstedtii was most frequently isolated, recent studies suggest C. parakroppenstedtii may be more prevalent than previously recognized. Antimicrobial susceptibility data revealed consistent resistance to beta-lactams and variable susceptibility to clindamycin and fluoroquinolones, whereas linezolid and vancomycin demonstrated consistent efficacy. Directed antibiotic therapy, particularly with lipophilic agents, combined with abscess drainage, was associated with improved outcomes and lower recurrence. In contrast, higher recurrence rates were reported with corticosteroids or immunosuppressants used in isolation.

These findings support a multimodal approach as the most effective strategy for CNGM management. Further prospective studies are needed to establish standardized diagnostic criteria and evidence-based treatment guidelines.

La mastitis granulomatosa neutrofílica quística (MGNQ) es un subtipo raro y poco reconocido de mastitis granulomatosa, cada vez más asociado a especies del género Corynebacterium, en particular Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii. A pesar del creciente número de publicaciones, su diagnóstico sigue siendo complejo y las estrategias terapéuticas varían considerablemente. Esta revisión sistemática tuvo como objetivo consolidar las características clínicas, microbiológicas y terapéuticas de la MGNQ para mejorar su abordaje clínico. Se realizó una búsqueda estructurada en PubMed utilizando términos MeSH, que identificó 13 estudios, de los cuales 11 cumplieron los criterios de inclusión. Estos estudios, que abarcan un total de 387 pacientes, fueron analizados en cuanto a presentación clínica, métodos diagnósticos, hallazgos histopatológicos, especies bacterianas identificadas, perfiles de sensibilidad antimicrobiana, estrategias de tratamiento y desenlaces clínicos. La MGNQ se presentó típicamente como una masa dolorosa unilateral en la mama, frecuentemente acompañada de abscesos, inversión del pezón o fístulas. El diagnóstico se estableció mediante estudio histopatológico y se confirmó con pruebas microbiológicas, habitualmente mediante MALDI-TOFMS o secuenciación del ARN 16S. Aunque C. kroppenstedtii fue la especie más frecuentemente aislada, estudios recientes sugieren que C. parakroppenstedtii podría estar infradiagnosticada. Los datos sobre sensibilidad antimicrobiana revelaron una resistencia constante a los beta-lactámicos y una susceptibilidad variable a clindamicina y fluoroquinolonas, mientras que linezolid y vancomicina demostraron una eficacia constante. El tratamiento antibiótico dirigido, especialmente con agentes lipofílicos, combinado con drenaje de abscesos, se asoció con mejores resultados y menor tasa de recurrencia. Por el contrario, se observaron mayores tasas de recurrencia con el uso aislado de corticosteroides o inmunosupresores. Estos hallazgos respaldan un enfoque terapéutico multimodal como la estrategia más eficaz para el manejo de la MGNQ. Se necesitan estudios prospectivos para establecer criterios diagnósticos estandarizados y guías terapéuticas basadas en la evidencia.

Granulomatous mastitis (GM) is an uncommon and complex inflammatory condition of the breast that primarily affects parous women of reproductive age, particularly in the post-lactational period.1,2 Clinically, it presents as a painful breast mass, often accompanied by erythema, abscess formation, or fistulae, and frequently mimics malignant lesions both clinically and radiologically.3,4 Although various etiologies have been proposed—ranging from autoimmune mechanisms and hormonal imbalances to infectious agents—the pathogenesis of GM remains incompletely understood.3,4

Histologically, GM encompasses a spectrum of inflammatory responses, including both poorly organized histiocytic infiltrates and well-formed granulomas, making the term a generic descriptor rather than a discrete clinical entity.4 As a result, several subtypes have been proposed to better reflect underlying causes and clinical behavior. Among these, lobular granulomatous mastitis (LGM) is often associated with autoimmune disease and exhibits a centrolobular distribution, whereas idiopathic granulomatous mastitis (IGM) is reserved for cases without identifiable etiology, following the exclusion of infectious or systemic causes.4,5 More recently, cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis (CNGM) has been distinguished as a unique subtype characterized by lipogranulomatous inflammation with cystic vacuoles and prominent neutrophilic infiltration.

First described by Renshaw etal. in 2011,6 CNGM is increasingly recognized in the literature but remains diagnostically challenging. CNGM appears to be more prevalent in certain ethnic groups, specifically Hispanic, African American, or individuals from Asia or Africa, and is less common among Caucasians.7 Clinically, this entity typically presents unilateral involvement, manifesting as a mass in the breast tissue, with nipple inversion, abscess formation, and the development of fistulous tracts. Less frequently, it may be accompanied by local pain, nipple discharge, and erythema.4,7 Bilateral presentation is also possible, though rare.7

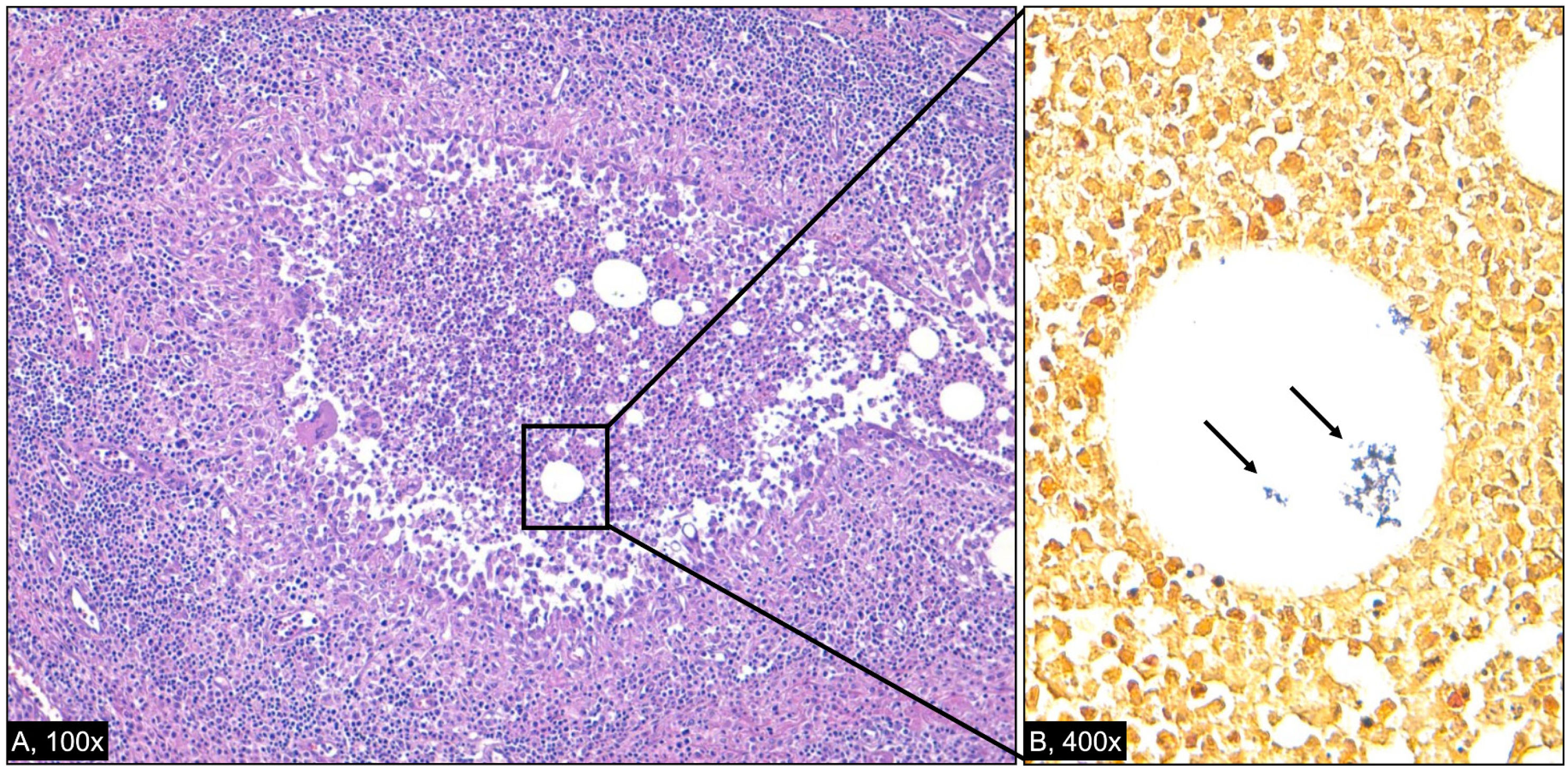

Histopathologically, CNGM is characterized by suppurative lipogranulomas consisting of central lipid vacuoles surrounded by neutrophils (and sometimes lymphocytes) and an outer layer of epithelioid histiocytes. Langhans-type giant cells may also be present,4 as well as coryneform bacteria that stain blue-violet with the Gram stain technique.3

In fact, a strong microbiological association has been established between CNGM and Corynebacterium spp., most notably Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii (CK)—a lipophilic, slow-growing, Gram-positive bacillus originally isolated in 1998.8 CK has since been reported in multiple case series, with some studies identifying it in over 50% of GM cases.3 However, recent evidence suggests that other related species, such as Corynebacterium parakroppenstedtii and C. tuberculostearicum, may be underrecognized due to limitations of standard laboratory techniques, particularly MALDI-TOFMS, which may misclassify isolates in the absence of confirmatory molecular sequencing.9

It is not always possible to identify a specific antecedent factor in cases of CNGM. However, data suggest that disruption of the cutaneous barrier, whether due to trauma or the breastfeeding process, may represent a potential route for infection.10 Subsequent colonization of the lactiferous ducts, with dissemination to the terminal lobular unit, is further facilitated by the lipid-rich environment of breast tissue, which promotes the growth and reproduction of Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii and the development of granulomas.3

Diagnosis of CNGM remains difficult due to the subtle and often delayed growth of Corynebacterium spp. in standard culture media, their frequent misidentification as skin contaminants, and the lack of widely recognized diagnostic criteria.4 Even when correctly identified, the clinical significance of these bacteria is often questioned, further complicating treatment decisions.

The therapeutic management of CNGM is highly variable and may include antibiotics, corticosteroids, immunosuppressants, or surgical interventions. Treatment is often empirical, and recurrence is common, particularly in the absence of targeted therapy based on antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Although some case series report good outcomes with lipophilic antibiotics or immunosuppressive regimens, no consensus exists regarding the optimal approach, and prospective data are lacking.4

Given the rarity of the condition and the variability in reported management strategies, the current body of literature remains fragmented and inconsistent. Most available studies are limited to isolated case reports or small retrospective cohorts, often lacking methodological standardization, microbiological confirmation, and long-termfollow-up. There is no consensus on diagnostic criteria, antimicrobial selection, or optimal therapeutic strategy. These limitations hinder the development of evidence-based clinical guidelines and delay accurate recognition and treatment of this condition.

To address this gap, we conducted a systematic review of the literature on Corynebacterium-associated granulomatous mastitis, with a focus on clinical presentation, histopathology, diagnostic methods, antimicrobial susceptibility patterns, therapeutic approaches, and patient outcomes. Our goal was to consolidate existing evidence, identify consistent trends, and provide a structured basis for future clinical and research efforts.

MethodsA structured literature search was conducted using the PubMed database to identify studies reporting clinical cases of granulomatous mastitis associated with Corynebacterium species. The search employed the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms “granulomatous mastitis” AND “Corynebacterium” and was limited to articles published between January 2015 and April 2025. Filters were applied to include only studies involving human subjects, published in English or Spanish, and with free full-text availability.

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they reported original clinical data on patients diagnosed with granulomatous mastitis and included confirmed microbiological identification of Corynebacterium spp., either through culture or molecular methods. Studies were excluded if they involved non-human data, lacked microbiological confirmation, or were available only as abstracts without full-text access. A total of 13 articles were initially identified, of which 2 were excluded based on the criteria described above. Ultimately, 11 studies were included in the final review.

Study selection and data extraction were performed byasingle reviewer. This approach was considered acceptabledue to the limited number of eligible studies and the exploratory nature of the analysis. For each included study, the following data were extracted: type of study, number of patients, clinical presentation, diagnostic and microbiological methods used, histopathological findings, Corynebacterium species identified, antimicrobial susceptibility testing (when available), therapeutic interventions, time to resolution, and recurrence. Extracted data were summarized and compared in tabular format to identify consistent patterns and trends.

No formal assessment of methodological quality or risk of bias was conducted. Given the descriptive objective of this review and the predominance of case reports and retrospective cohorts, the focus was placed on consolidating clinical and microbiological information rather than performing critical appraisal or meta-analysis. Additional references identified through cross-referencing were used to support the theoretical framework, particularly regarding disease pathogenesis, diagnostic challenges, and evolving treatment strategies. These were not included in the formal review dataset.

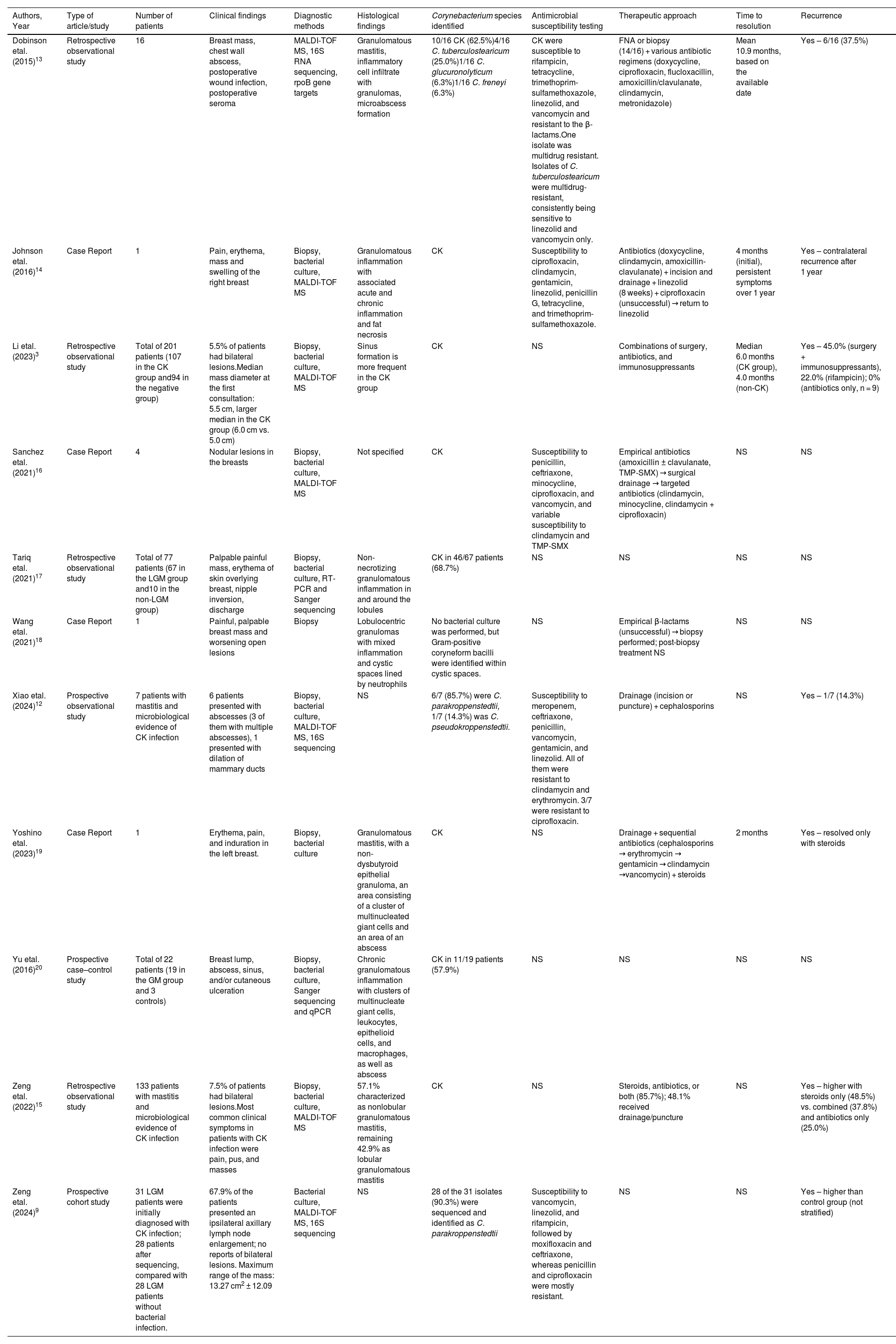

ResultsA total of 11 studies met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed in this systematic review. These included 4 case reports, 3 retrospective cohort studies, 2 prospective cohort or observational studies, 1 case–control study, and 1 retrospective observational study. Collectively, these studies reported on 387 patients diagnosed with granulomatous mastitis associated with Corynebacterium spp.

The clinical presentation was heterogeneous across studies, but the most common finding was a painful, palpable breast mass, frequently associated with abscess formation, erythema, nipple inversion, and occasionally fistulae. Bilateral involvement was infrequent, ranging from 5.5% to 7.5% in larger cohorts. The median size of breast lesions varied between 5.0 and 6.0 cm, with larger diameters often reported in patients with confirmed Corynebacterium infection.

Diagnosis was typically established via pathological biopsy, often complemented by bacterial culture and advanced molecular methods, including MALDI-TOFMS, 16S rRNA sequencing, and in some cases, rpoB gene amplification. Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii was the most frequently isolated species, identified in up to 68.7% of cases in certain cohorts. However, more recent data suggest the presence of C. parakroppenstedtii as the predominant isolate in some series.

Histopathological findings were consistent with granulomatous inflammation, often presenting as lipogranulomas with central vacuoles, neutrophilic infiltration, epithelioid histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells. In some cases, Gram-positive bacilli were identified within cystic spaces.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing was inconsistently reported. When performed, CK isolates showed susceptibility to linezolid, vancomycin, rifampicin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, with frequent resistance to β-lactams, macrolides, and in some cases, quinolones. Notably, multidrug-resistant strains were reported, particularly for C. tuberculostearicum and C. kroppenstedtii.

The therapeutic approaches varied widely and included combinations of antibiotic therapy, corticosteroids or other immunosuppressants, and surgical interventions such as abscess drainage or excision. In some studies, antibiotics alone yielded favorable outcomes with lower recurrence rates, while others reported high recurrence when corticosteroids were used in isolation. Directed therapy, particularly when guided by susceptibility testing, appeared more effective in reducing recurrence.

The time to clinical resolution ranged from 2 to 10.9 months, with a median of approximately 5–6 months in larger cohorts. Recurrence rates were variable across studies, reaching up to 45% in patients treated with surgery combined with immunosuppressants, and significantly lower (0–14%) in those managed with antibiotics alone or with drainage.

A summary of the clinical, microbiological, and therapeutic characteristics of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

Overview of published cases of Corynebacterium-associated granulomatous mastitis: clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes.

| Authors, Year | Type of article/study | Number of patients | Clinical findings | Diagnostic methods | Histological findings | Corynebacterium species identified | Antimicrobial susceptibility testing | Therapeutic approach | Time to resolution | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dobinson etal. (2015)13 | Retrospective observational study | 16 | Breast mass, chest wall abscess, postoperative wound infection, postoperative seroma | MALDI-TOF MS, 16S RNA sequencing, rpoB gene targets | Granulomatous mastitis, inflammatory cell infiltrate with granulomas, microabscess formation | 10/16 CK (62.5%)4/16 C. tuberculostearicum (25.0%)1/16 C. glucuronolyticum (6.3%)1/16 C. freneyi (6.3%) | CK were susceptible to rifampicin, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, linezolid, and vancomycin and resistant to the β-lactams.One isolate was multidrug resistant. Isolates of C. tuberculostearicum were multidrug-resistant, consistently being sensitive to linezolid and vancomycin only. | FNA or biopsy (14/16) + various antibiotic regimens (doxycycline, ciprofloxacin, flucloxacillin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, clindamycin, metronidazole) | Mean 10.9 months, based on the available date | Yes – 6/16 (37.5%) |

| Johnson etal. (2016)14 | Case Report | 1 | Pain, erythema, mass and swelling of the right breast | Biopsy, bacterial culture, MALDI-TOF MS | Granulomatous inflammation with associated acute and chronic inflammation and fat necrosis | CK | Susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, clindamycin, gentamicin, linezolid, penicillin G, tetracycline, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. | Antibiotics (doxycycline, clindamycin, amoxicillin-clavulanate) + incision and drainage + linezolid (8 weeks) + ciprofloxacin (unsuccessful) → return to linezolid | 4 months (initial), persistent symptoms over 1 year | Yes – contralateral recurrence after 1 year |

| Li etal. (2023)3 | Retrospective observational study | Total of 201 patients (107 in the CK group and94 in the negative group) | 5.5% of patients had bilateral lesions.Median mass diameter at the first consultation: 5.5 cm, larger median in the CK group (6.0 cm vs. 5.0 cm) | Biopsy, bacterial culture, MALDI-TOF MS | Sinus formation is more frequent in the CK group | CK | NS | Combinations of surgery, antibiotics, and immunosuppressants | Median 6.0 months (CK group), 4.0 months (non-CK) | Yes – 45.0% (surgery + immunosuppressants), 22.0% (rifampicin); 0% (antibiotics only, n = 9) |

| Sanchez etal. (2021)16 | Case Report | 4 | Nodular lesions in the breasts | Biopsy, bacterial culture, MALDI-TOF MS | Not specified | CK | Susceptibility to penicillin, ceftriaxone, minocycline, ciprofloxacin, and vancomycin, and variable susceptibility to clindamycin and TMP-SMX | Empirical antibiotics (amoxicillin ± clavulanate, TMP-SMX) → surgical drainage → targeted antibiotics (clindamycin, minocycline, clindamycin + ciprofloxacin) | NS | NS |

| Tariq etal. (2021)17 | Retrospective observational study | Total of 77 patients (67 in the LGM group and10 in the non-LGM group) | Palpable painful mass, erythema of skin overlying breast, nipple inversion, discharge | Biopsy, bacterial culture, RT-PCR and Sanger sequencing | Non-necrotizing granulomatous inflammation in and around the lobules | CK in 46/67 patients (68.7%) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Wang etal. (2021)18 | Case Report | 1 | Painful, palpable breast mass and worsening open lesions | Biopsy | Lobulocentric granulomas with mixed inflammation and cystic spaces lined by neutrophils | No bacterial culture was performed, but Gram-positive coryneform bacilli were identified within cystic spaces. | NS | Empirical β-lactams (unsuccessful) → biopsy performed; post-biopsy treatment NS | NS | NS |

| Xiao etal. (2024)12 | Prospective observational study | 7 patients with mastitis and microbiological evidence of CK infection | 6 patients presented with abscesses (3 of them with multiple abscesses), 1 presented with dilation of mammary ducts | Biopsy, bacterial culture, MALDI-TOF MS, 16S sequencing | NS | 6/7 (85.7%) were C. parakroppenstedtii, 1/7 (14.3%) was C. pseudokroppenstedtii. | Susceptibility to meropenem, ceftriaxone, penicillin, vancomycin, gentamicin, and linezolid. All of them were resistant to clindamycin and erythromycin. 3/7 were resistant to ciprofloxacin. | Drainage (incision or puncture) + cephalosporins | NS | Yes – 1/7 (14.3%) |

| Yoshino etal. (2023)19 | Case Report | 1 | Erythema, pain, and induration in the left breast. | Biopsy, bacterial culture | Granulomatous mastitis, with a non-dysbutyroid epithelial granuloma, an area consisting of a cluster of multinucleated giant cells and an area of an abscess | CK | NS | Drainage + sequential antibiotics (cephalosporins → erythromycin → gentamicin → clindamycin →vancomycin) + steroids | 2 months | Yes – resolved only with steroids |

| Yu etal. (2016)20 | Prospective case–control study | Total of 22 patients (19 in the GM group and 3 controls) | Breast lump, abscess, sinus, and/or cutaneous ulceration | Biopsy, bacterial culture, Sanger sequencing and qPCR | Chronic granulomatous inflammation with clusters of multinucleate giant cells, leukocytes, epithelioid cells, and macrophages, as well as abscess | CK in 11/19 patients (57.9%) | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Zeng etal. (2022)15 | Retrospective observational study | 133 patients with mastitis and microbiological evidence of CK infection | 7.5% of patients had bilateral lesions.Most common clinical symptoms in patients with CK infection were pain, pus, and masses | Biopsy, bacterial culture, MALDI-TOF MS | 57.1% characterized as nonlobular granulomatous mastitis, remaining 42.9% as lobular granulomatous mastitis | CK | NS | Steroids, antibiotics, or both (85.7%); 48.1% received drainage/puncture | NS | Yes – higher with steroids only (48.5%) vs. combined (37.8%) and antibiotics only (25.0%) |

| Zeng etal. (2024)9 | Prospective cohort study | 31 LGM patients were initially diagnosed with CK infection; 28 patients after sequencing, compared with 28 LGM patients without bacterial infection. | 67.9% of the patients presented an ipsilateral axillary lymph node enlargement; no reports of bilateral lesions. Maximum range of the mass: 13.27 cm2 ± 12.09 | Bacterial culture, MALDI-TOF MS, 16S sequencing | NS | 28 of the 31 isolates (90.3%) were sequenced and identified as C. parakroppenstedtii | Susceptibility to vancomycin, linezolid, and rifampicin, followed by moxifloxacin and ceftriaxone, whereas penicillin and ciprofloxacin were mostly resistant. | NS | NS | Yes – higher than control group (not stratified) |

CK – Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii; FNA – fine-needle aspiration; GM – granulomatous mastitis; LGM – lobular granulomatous mastitis; MALTI-TOF MS – Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-Of-Flight Mass Spectrometry; NS – not specified; PCR – polymerase chain reaction; rpoB – RNA polymerase β-subunit gene; RT-PCR – reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; TMP-SMX – trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

This systematic review consolidates the existing clinical and microbiological data on cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis associated with Corynebacterium species and provides a structured comparative analysis of the available literature. While CNGM has long been recognized as a histopathological variant within the broader category of granulomatous mastitis, its distinct clinical behavior and microbiological associations increasingly support its classification as a separate clinical entity. However, its definition remains in evolution, and no universally accepted diagnostic criteria exist.4

Across the reviewed studies, the most consistent clinical presentation was that of a unilateral painful breast mass, frequently accompanied by signs of inflammation such as erythema, nipple inversion, or abscess formation. Bilateral cases were less frequent but documented. Radiological features, when described, were often non-specific and mimicked malignant lesions, leading to biopsy in most instances.4

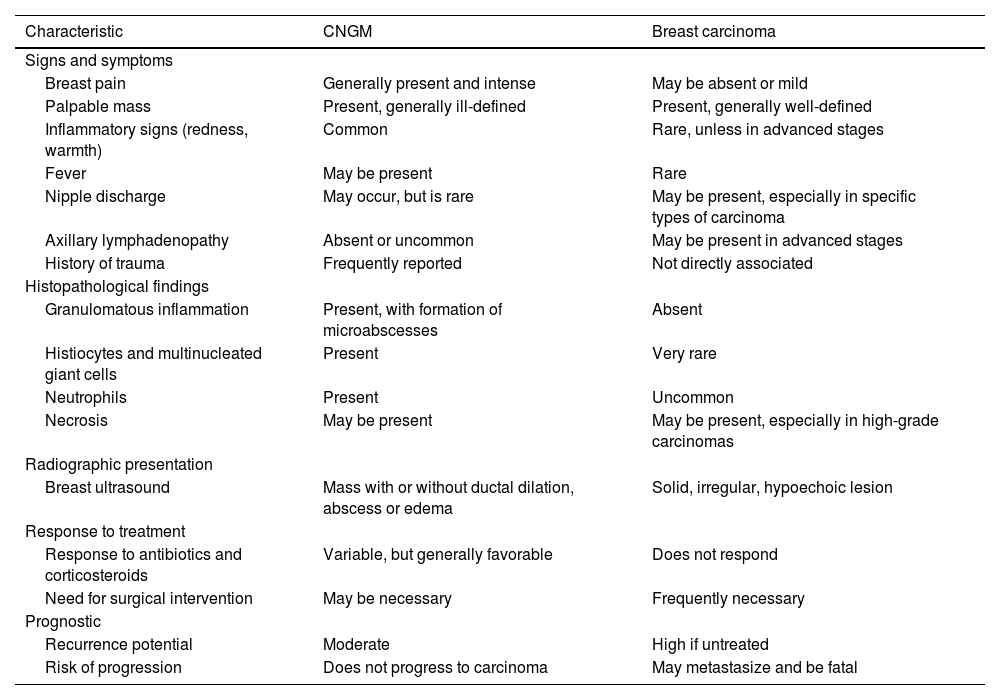

Given its varied presentation, CNGM must be carefully differentiated from both malignant and benign conditions of the breast. Breast carcinoma remains the most critical differential diagnosis due to its overlapping clinical and radiological characteristics. Table 2 outlines the main similarities and differences between these two etiologies. Once malignancy is excluded, infectious causes of granulomatous mastitis should be considered. Bacterial infections are the most common and can be polymicrobial, with the Pseudomonas genus identified as the most frequent.4 Tuberculous mastitis is also a significant differential diagnosis, particularly in endemic areas. Other less common pathogens that may lead to mastitis with granulomatous presentation include Bartonella henselae, atypical mycobacteria (especially in immunocompromised patients), Actinomyces, Brucella, fungi (particularly Histoplasma capsulatum), and parasites.4,11 Subareolar breast abscesses, strongly associated with smoking habits, can also mimic CNGM due to their clinical and histological presentation.4 Foreign body granulomas and fat necrosis of the breast can also present as masses, although they are typically painless.4 Finally, other non-infectious inflammatory processes, such as sarcoidosis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and rheumatoid arthritis, should also be considered.4,5

Differences and similarities in clinical and radiographic presentation, management, and prognosis of cystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis associated with Corynebacterium and breast carcinoma.

| Characteristic | CNGM | Breast carcinoma |

|---|---|---|

| Signs and symptoms | ||

| Breast pain | Generally present and intense | May be absent or mild |

| Palpable mass | Present, generally ill-defined | Present, generally well-defined |

| Inflammatory signs (redness, warmth) | Common | Rare, unless in advanced stages |

| Fever | May be present | Rare |

| Nipple discharge | May occur, but is rare | May be present, especially in specific types of carcinoma |

| Axillary lymphadenopathy | Absent or uncommon | May be present in advanced stages |

| History of trauma | Frequently reported | Not directly associated |

| Histopathological findings | ||

| Granulomatous inflammation | Present, with formation of microabscesses | Absent |

| Histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells | Present | Very rare |

| Neutrophils | Present | Uncommon |

| Necrosis | May be present | May be present, especially in high-grade carcinomas |

| Radiographic presentation | ||

| Breast ultrasound | Mass with or without ductal dilation, abscess or edema | Solid, irregular, hypoechoic lesion |

| Response to treatment | ||

| Response to antibiotics and corticosteroids | Variable, but generally favorable | Does not respond |

| Need for surgical intervention | May be necessary | Frequently necessary |

| Prognostic | ||

| Recurrence potential | Moderate | High if untreated |

| Risk of progression | Does not progress to carcinoma | May metastasize and be fatal |

Histologically, the hallmark of CNGM is the presence of cystic lipogranulomas with central lipid vacuoles surrounded by neutrophils and epithelioid histiocytes, as illustrated in Fig. 1. This image corresponds to the histopathological findings of a patient followed in our outpatient clinic, whose case initially prompted our interest in exploring this topic in greater depth. While some studies identified Gram-positive bacilli within these vacuoles, this was not a consistent finding. The difficulty in recovering Corynebacterium species from clinical specimens is well documented and may contribute to underdiagnosis. Their lipophilic nature, slow growth, and frequent misclassification as skin contaminants underline the need for close microbiological-pathological collaboration and for informing laboratory personnel when CNGM is suspected. Culture supplemented by MALDI-TOFMS, and ideally confirmed with 16S rRNA or rpoB gene sequencing, remains the cornerstone of accurate microbial identification.

Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii(CK) was the most frequently isolated species, often detected through culture or molecular testing. However, recent studies, such as Zeng etal. and Xiao etal.,9,12 have demonstrated the presence of closely related species, particularly C. parakroppenstedtii, which was identified in 85–90% of isolates initially presumed to be CK. This highlights a taxonomic gap in routine clinical identification and suggests that CK may have been overrepresented in earlier reports relying solely on MALDI-TOF.

The selection of the optimal antimicrobial regimen should consider the results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing and the minimum inhibitory concentration for each drug, the lipophilic properties of Corynebacterium spp., and the physicochemical properties of the lipogranulomatous spaces.13 Considering their lipophilic characteristics, with a high volume of distribution and bactericidal activity, literature often reports clarithromycin, rifampicin, clindamycin, and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole as the drugs of choice.11 On the other hand, due to the low lipid solubility of beta-lactams and quinolones, these drugs are generally considered to be of limited utility in treating this clinical entity.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing revealed consistent trends across the reviewed studies, despite incomplete reporting in nearly half of them. Linezolid and vancomycin emerged as the most reliably active agents against Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii and related species, including multidrug-resistant strains. In cases where resistance was documented, these two agents were often the only antibiotics demonstrating sustained in vitro efficacy. While rifampicin also showed frequent susceptibility in laboratory testing, clinical outcomes were less consistent; notably, the study by Li etal.,3 reported a significantly higher recurrence rate among patients treated with rifampicin, raising concerns about its in vivo effectiveness despite favorable pharmacokinetics. Beta-lactams, including penicillin and amoxicillin, were uniformly ineffective, reflecting the intrinsic resistance profile of lipophilic Corynebacterium species. Susceptibility to clindamycin and ciprofloxacin varied widely, with several studies reporting complete resistance. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole and doxycycline showed moderate activity, but therapeutic success appeared context-dependent and was not uniformly observed. In the current review, multiple patients across different studies received doxycycline, either alone or in combination with other agents, yet outcomes were inconsistent. For instance, Johnson etal.,14 reported a case in which doxycycline failed to produce clinical improvement, requiring escalation to incision and drainage followed by linezolid. Similarly, Li etal.,3 and Dobinson etal.,13 also documented cases where doxycycline was used but did not prevent recurrence. These findings contrast with the report by Naik etal.,1 who described two cases successfully managed with doxycycline following Renshaw's recommendations,6 highlighting its potential efficacy when used in carefully selected cases. This finding calls for caution and further investigation, as it raises the possibility that both rifampicin and doxycycline's efficacy may be influenced by patient selection, treatment context, or strain-specific resistance mechanisms not captured by conventional AST.

Treatment strategies for CNGM varied widely across the studies reviewed, reflecting the absence of standardized guidelines and the evolving understanding of this condition. Management approaches ranged from isolated antibiotic therapy to the use of immunosuppressants and surgical interventions. The average time required for resolution of the inflammatory process is reported in the literature to be approximately 5 months,3 which aligns with the findings of this review. Despite the heterogeneity in treatment regimens, a trend can be discerned: patients who received directed antibiotic therapy—particularly with lipophilic agents and following microbiological identification—generally experienced shorter time to resolution and lower recurrence rates, as reported in Dobinson etal.,13 Johnson etal.,14 and Xiao etal.12 Conversely, the use of corticosteroids alone or surgery combined with immunosuppressants was associated with higher recurrence, notably in the series by Li etal.,3 and Zeng etal.15

Based on these findings, the authors advocate for a multimodal approach to treatment. This should begin with accurate microbiological identification and targeted antibiotic therapy, preferably using lipophilic agents with favorable tissue penetration. In cases presenting with abscesses, prompt surgical drainage is recommended. For patients with slow clinical resolution or recurrent disease, corticosteroids may be cautiously introduced, ideally in conjunction with antimicrobial treatment. Although corticosteroids have demonstrated efficacy in LGM, their role in CNGM remains less clearly defined, particularly given the infectious etiology and risk of exacerbating disease if used in isolation.4,13

Surgical intervention, including percutaneous or open drainage, is often necessary when abscesses are present. However, aggressive surgical management should be avoided where possible, given recurrence risks and potential for disfigurement. While minimally invasive strategies are increasingly favored in LGM,4 their applicability to CNGM requires further evaluation.

The findings of this review must be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the rarity of CNGM limits the availability of large-scale studies. Most included publications were small cohort studies or isolated case reports, with varying methodological quality. Differences in study design, sample size, and diagnostic criteria pose challenges to comparability. The patient populations were also heterogeneous, with variations in ethnicity, clinical presentation, and comorbidities that may influence disease progression and response to therapy. Furthermore, therapeutic regimens were not standardized, and recurrence definitions and follow-up durations varied across studies. Susceptibility testing, when performed, often lacked uniform reporting standards, complicating direct comparison between studies.

Despite these limitations, this review allows for a clearer understanding of the clinical and microbiological landscape of CNGM and offers a structured overview that may inform future diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms. A critical next step in advancing the management of this condition will be the establishment of prospective multicenter studies and the development of consensus guidelines.

ConclusionCystic neutrophilic granulomatous mastitis associated with Corynebacterium species represents a distinct and likely underrecognized clinical entity within the spectrum of granulomatous mastitis. This systematic review provides a comprehensive synthesis of its clinical presentation, diagnostic challenges, microbiological landscape, and therapeutic variability. While Corynebacterium kroppenstedtii remains the most frequently identified pathogen, recent data suggest that other closely related species may be more prevalent than previously recognized, underscoring the need for improved diagnostic tools, particularly beyond MALDI-TOF MS.

Despite significant heterogeneity across the literature, this review identifies a clear trend favoring microbiologically guided, lipophilic antibiotic therapy—often combined with timely surgical drainage—as the most effective strategy. Isolated use of corticosteroids or immunosuppressants was associated with higher recurrence, emphasizing the importance of a multimodal, individualized approach. However, the evidence base remains limited by the predominance of retrospective studies, small sample sizes, and inconsistent reporting.

Moving forward, prospective multicenter studies with standardized diagnostic criteria, antimicrobial susceptibility testing, and outcome measures are essential to optimize care for patients with CNGM. Until such guidelines are established, clinical decision-making should be grounded in careful microbiological confirmation and adapted to individual disease severity and response.

Ethical considerationsThe study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All personal data and sensitive information were handled to ensure confidentiality and privacy. The data were anonymized to prevent the direct or indirect identification of the patient involved. Informed consent was obtained from the patient, ensuring that she was fully informed about the study's objectives, as well as the potential risks and benefits associated with her participation.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author ContributionsAndré R. Guimarães: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ana Pereira Marques: Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. António Sarmento: Conceptualization, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing.

We hereby declare that none of the authors have any conflicts of interest in relation to this manuscript. The research presented in this paper was conducted with the utmost impartiality and integrity, and there are no financial or personal relationships that could be construed as influencing the results or interpretations of this study. All authors affirm that they have no affiliations or financial interests that would constitute a conflict of interest.

We extend our gratitude to all authors for their essential contributions to this work and to the clinical team for their support in managing the case. We also thank Professora Doutora Lurdes Santos and Doutora Isabel Amendoeira for their valuable input in the final review of the manuscript and for their assistance with the submission.