Prostate cancer is the first cause of mortality related to malignancy in Mexican men. Common clinical practice has to be evaluated in order to gain a picture of reality apart from the guidelines.

AimTo analyze clinical practice among urologists in Mexico in relation to prostate cancer management and to compare the results with current recommendations and guidelines.

MethodsWe collected the data from 600 urologists, members of the Sociedad Mexicana de Urología, who were invited by email to answer a survey on their usual decisions when managing controversial aspects of prostate cancer patients.

ResultsQuinolones were the most common antibiotic used as prophylaxis in prostate biopsy (75.51%); 10–12 cores were taken in more than 65% of prostate biopsies; and 18.27% of the participants performed limited pelvic lymphadenectomy. Treatment results showed that 10.75% of the urologists surveyed preferred radical prostatectomy as monotherapy in high-risk patients with extraprostatic extension and 60.47% used complete androgen deprivation in metastatic prostate cancer.

ConclusionsThere are many areas of opportunity for improvement in our current clinical practice for the management of patients with prostate cancer.

El cáncer de próstata es la primera causa de mortalidad relacionada a malignidad en hombres mexicanos. El manejo clínico tiene que ser evaluado para indagar sobre la correlación entre la práctica diaria y las guías establecidas.

ObjetivoAnalizar la práctica clínica entre urólogos Mexicanos acerca del manejo en cáncer de próstata y evaluarlo con respecto a las guías y recomendaciones.

MétodosSe mandó una invitación vía e-mail a 600 miembros de la Sociedad Mexicana de Urología para contestar una encuesta acerca del manejo de cáncer de próstata.

ResultadosEl antibiótico más usado para profilaxis en la biopsia de próstata fueron las quinolonas (75.51%); acerca de la biopsia de próstata, 65% de la población tomaba entre 10-12 muestras; 18.27% de los participantes realizaban una linfadenectomia limitada. 10.75% de los encuestados preferían una prostatectomía radical como monoterapia en los pacientes de alto riesgo con extensión extraprostática y 64.47% de los urólogos usaron el bloqueo androgénico completo en el cáncer de próstata metastásico.

ConclusionesHay múltiples áreas de oportunidad para mejorar en la actual práctica clínica en el manejo de pacientes con cáncer de próstata.

Prostate cancer (CaP) is one of the most important healthcare problems for adult men in Mexico. In 2013, this common malignancy was the leading cause of death associated with cancer in men in Mexico.1 In 2014, there were 233,000 new cases of patients with CaP. Mortality was about 13 deaths per 100,000 men.2 CaP is a very common concern in the daily clinical practice of every urologist and its adequate management and treatment are crucial for increasing life expectancy and quality of life in the patients with this disease.

To the best of our knowledge, there are no reports in Mexico that evaluate the clinical practice and decision-making of Mexican urologists, and therefore it is necessary to create studies that assess these aspects.

The aim of this article was to analyze clinical practice among urologists in Mexico in relation to controversial subjects of CaP management and to compare the results with the national and international recommendations.

MethodsAn online survey called Práctica Clínica de Urólogos de México (PCUMex) (Clinical Practice of Mexican Urologists) was employed. This questionnaire was available on the Survey Monkey website (https://es.surveymonkey.com/r/BKVXPFV). An invitation email was sent to 600 physicians belonging to the national urologic society, Sociedad Mexicana de Urología (SMU). Two reminder emails were sent after one and 2 weeks. The website was open from April to May 2013 and there was only one opportunity to fill out the questionnaire per email link. Website access was anonymous and no traceable or personal data was gathered. The study included 20 multiple choice closed-ended questions.

The results were evaluated through a descriptive analysis and a critical evidence-based discussion.

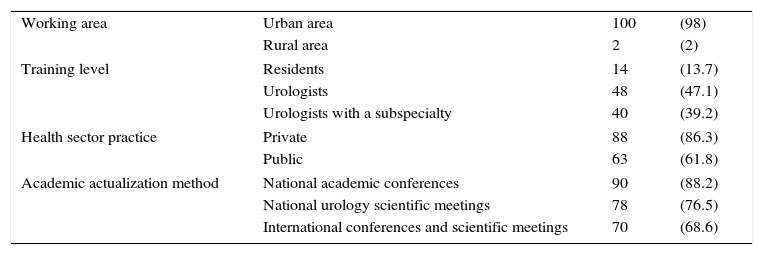

Results and discussionA total of 102 physicians participated in the survey; 100 (98%) were men and 2 (2%) were women. Table 1 describes the rest of the demographic and academic variables.

Demographic information (n [%]).

| Working area | Urban area | 100 | (98) |

| Rural area | 2 | (2) | |

| Training level | Residents | 14 | (13.7) |

| Urologists | 48 | (47.1) | |

| Urologists with a subspecialty | 40 | (39.2) | |

| Health sector practice | Private | 88 | (86.3) |

| Public | 63 | (61.8) | |

| Academic actualization method | National academic conferences | 90 | (88.2) |

| National urology scientific meetings | 78 | (76.5) | |

| International conferences and scientific meetings | 70 | (68.6) | |

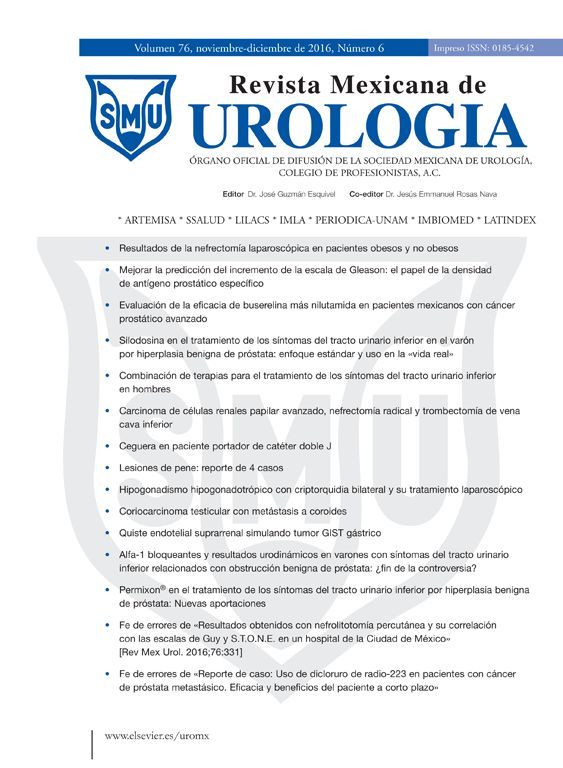

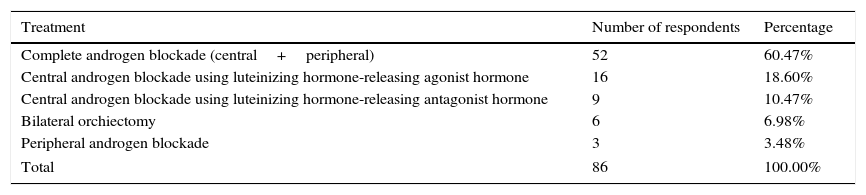

Bowel preparation or a cleansing enema before biopsy decrease the amount of feces in the rectum and potentially enable better visualization for prostate imaging. In our population, most of the clinicians used a rectal enema as pre-biopsy preparation (Fig. 1). According to the Canadian Urology Association (CUA) guidelines, the effect of bowel preparation on infection is debatable and it is a practice that has been abandoned due to patient cost, inconvenience, and the lack of data supporting the effect of prophylaxis.3 In fact, some authors suggest that the enema increases the odds of infection because it liquidizes the feces.4 Lindert compared the incidence of bacteriuria and bacteremia in patients with or without enema use. The results showed that the enema reduced the incidence of bacteremia, but it was asymptomatic in most of the cases.5 In an alternate study, a clear-fluid diet and the use of intestinal preparation showed no significant difference in the rate of post-biopsy sepsis.6 We conclude that bowel preparation has no impact as antibacterial prophylaxis and can be eliminated in clinical practice to avoid inconvenience to the patients, given that no proven benefit has been demonstrated.

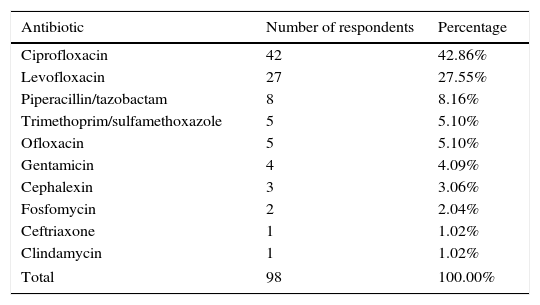

Question 2: first-line antibiotic prophylaxis in prostate biopsyAntibiotic prophylaxis is suggested for all patients before biopsy. The medication has to be effective for the flora in the rectum and genitourinary tract, especially Gram-negative bacteria. Quinolones are the treatment of choice according to the CUA and European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines.3,7 The recommendations suggest the application of antibiotic 1-h prior to the biopsy and 2–3 days after the procedure. In the Mexican population and other countries, such as India or in Africa, the rates of resistance to quinolones are high.8,9 The data in our institution showed that quinolone resistance could be as high as 61%. In Mexico, the reported resistance ranges from 24 to 50%, which rules out these antibiotics as a viable option.10

In our survey, the data showed that 74 (75.51%) participants used quinolones as first-line antibiotic prophylaxis (Table 2). Even though they may be following the advice of international guidelines, the rates of infective complications due to the increased resistance to fluoroquinolones after prostate biopsy are 2.4–7.5%.11 In our institution, a previous study encouraged the use of a single dose of piperacillin/tazobactam before the biopsy as prophylaxis in prostate biopsy due to high resistance to narrower-spectrum antibiotics.11 According to recent results from our institution that are awaiting publication, the best options at our hospital might be: amikacin, ertapenem, fosfomycin, and nitrofurantoin. We conclude that quinolones should not be used as antibiotic prophylaxis and the decision-making should be tailored according to local resistance patterns.

First-line antibiotic prophylaxis in prostate biopsy.

| Antibiotic | Number of respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | 42 | 42.86% |

| Levofloxacin | 27 | 27.55% |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 8 | 8.16% |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 5 | 5.10% |

| Ofloxacin | 5 | 5.10% |

| Gentamicin | 4 | 4.09% |

| Cephalexin | 3 | 3.06% |

| Fosfomycin | 2 | 2.04% |

| Ceftriaxone | 1 | 1.02% |

| Clindamycin | 1 | 1.02% |

| Total | 98 | 100.00% |

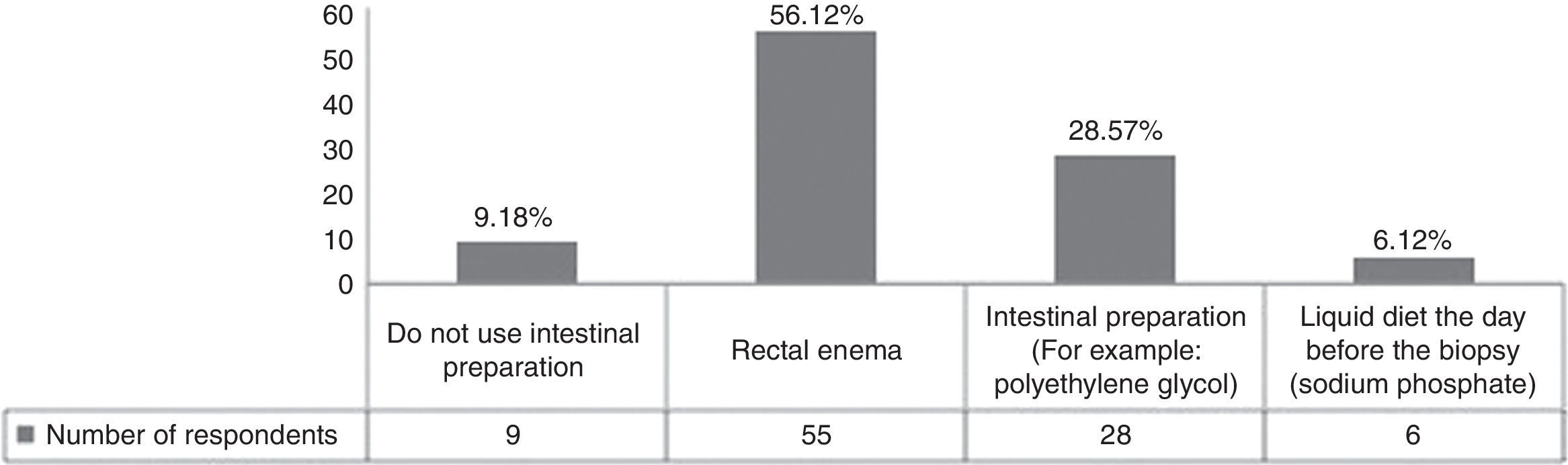

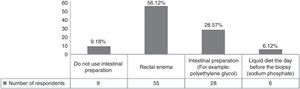

There is no consensus on the number of cores and their location in prostate cancer biopsy. Originally the standard sextant biopsy scheme consisted of 6 cores (one from the base, mid zone, and apex, bilaterally), but this pattern has produced false negatives and on average, 30% of the cancers are missed by the sextant biopsy scheme.12 The survey results showed that 3 (3.23%) of the urologists continued to use this inefficient/obsolete scheme (Fig. 2). On the other hand, EAU recommendations state that for prostate volumes of 30–40mL, more than 8 cores should be sampled. The current recommendation is that 10–12 core biopsies is the ideal approach and our results showed that more than 65% of the participants adequately followed this advice.7 In fact, the Mexican guidelines suggest that in a prostate biopsy, the physician should take at least 10–12 cores and the number can be higher for very large prostate volumes.13 A percentage of our population (11.85%) took more than 12 cores in the biopsy. However, taking more than 12 cores added no significant benefit to the diagnosis of prostate cancer (Fig. 2).14 Five participants took cores from the transition zone. According to the literature, the transition zone should be biopsied in men with a gland size greater than 50mL, because the additional yield in cancer detection is 15%.15 We reiterate that in the first transrectal prostate biopsy, the number of cores cannot be less than 10 or more than 16.

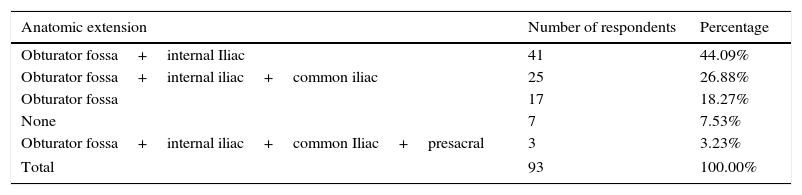

Question 4: pelvic lymphadenectomy in radical retropubic prostatectomy surgery in low/medium prostate cancer riskPelvic lymphadenectomy (PL) remains the most accurate procedure for detecting nodal involvement and gives more accurate information for prognosis after analyzing the number of lymph nodes involved and the capsule ruptured by the malignancy.16Table 3 shows that 7 participants (7.53%) did not perform lymphadenectomy, whereas 86 subjects (92.47%) performed PL in at least one anatomic zone. The decision to carry out lymphadenectomy is based on the likelihood of metastasis in the lymph nodes and the percentage of patients at low-risk, medium-risk, and high-risk for the possibility of metastasis is <5%, 3.7-20-1%, and 15–40%, respectively.7 There is a consensus that the approach to lymph node dissection in low-risk patients is not indicated.7 A minimum sector of our survey sample did not remove lymph nodes. This is probably because many of the patients are categorized as medium-risk. However, practice in regard to surgical decisions is controversial in this group of patients. The EAU and Mexican guidelines recommend pelvic lymphadenectomy in medium/high-risk subjects.7,13 The American Urological Association (AUA) states that PL is generally reserved for high-risk patients.17 In summary, the PL in medium-risk subjects is indicated if the risk for positive nodes is >5%.7 Concerning PL extension, obturator fossa lymphadenectomy is not sufficient, because it will miss approximately 50% of metastases.18 Hence, the iliac region must be included.

Type of pelvic lymphadenectomy in radical retropubic prostatectomy surgery in low/medium risk prostate cancer.

| Anatomic extension | Number of respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Obturator fossa+internal Iliac | 41 | 44.09% |

| Obturator fossa+internal iliac+common iliac | 25 | 26.88% |

| Obturator fossa | 17 | 18.27% |

| None | 7 | 7.53% |

| Obturator fossa+internal iliac+common Iliac+presacral | 3 | 3.23% |

| Total | 93 | 100.00% |

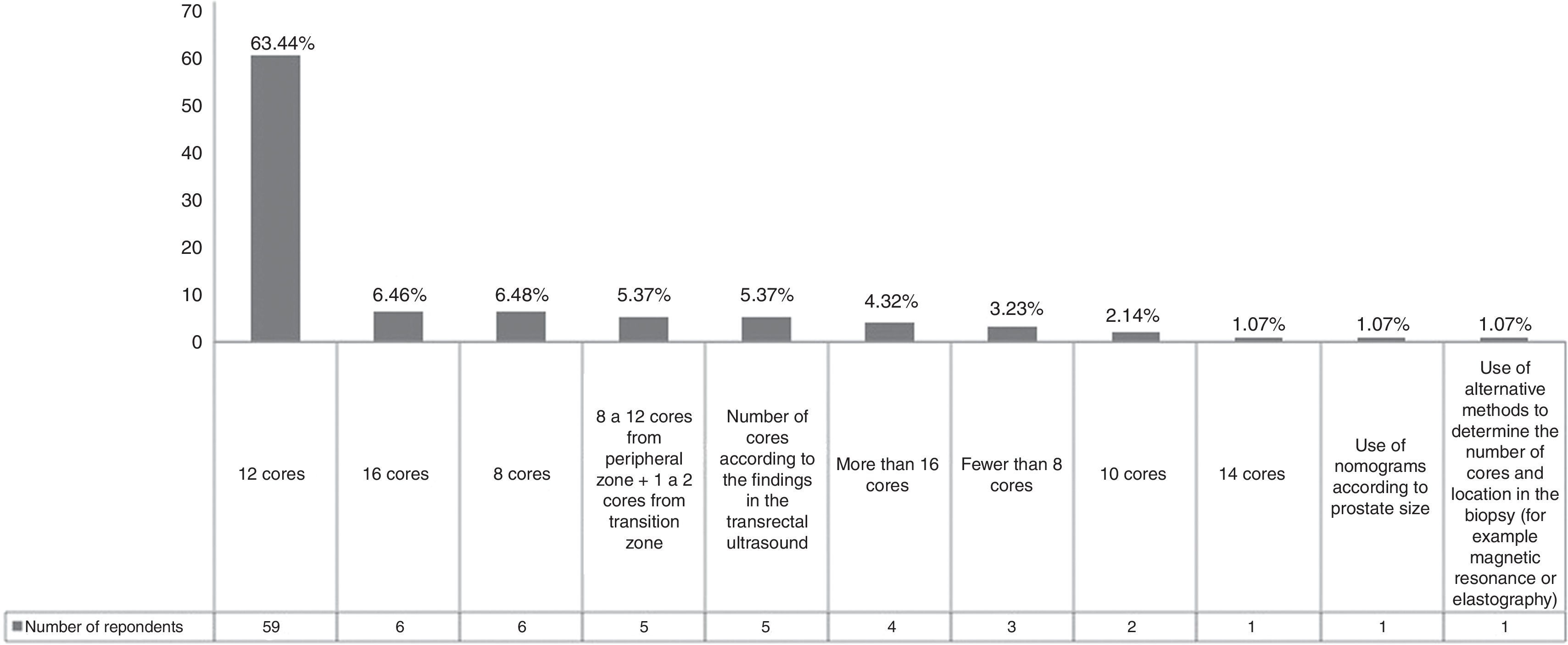

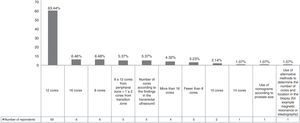

Erectile dysfunction after radical retropubic prostatectomy (RRP) is a common consequence of the surgery. The erectile function rates are from 11 to 87% after RRP.19 The factors that have an impact on the recovery of erectile function after radical prostatectomy are: patient age, preoperative potency status, and the ability to preserve both neurovascular bundles.15 In our sample, 84 physicians (90.32%) prescribed a phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor and 2 urologists (2.16%) prescribed intracavernous injections (ICIs) for penile rehabilitation (Fig. 3). The EAU guidelines specify that this topic remains controversial because placebo studies have not shown a definite benefit when compared with daily administration of vardenafil or sildenafil or compared with on-demand sildenafil administration.7 In contrast to this information, there is a previous trial that suggests that 10 and 20mg vardenafil doses on demand were superior to placebo when evaluated with the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF).20 Other trials showed that a daily dose of tadalafil was more effective than placebo or tadalafil on demand,21 but another trial comparing a nighttime dose of sildenafil versus on-demand doses did not find any differences.22 It has been suggested that ICI is efficacious in improving erectile function, compared with patients that do not receive any treatment.23 Some trials suggest that the range of ICI effectiveness is 30–55%, and that the role of these drugs in combination with sildenafil can decrease sildenafil failures.24 With the evidence that is available, while waiting for higher levels of evidence, the use of phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors is the potential first-line treatment in penile rehabilitation after RRP, with ICI as second-line treatment in patients that do not respond to oral medications or that undergo non-nerve-sparing surgery.

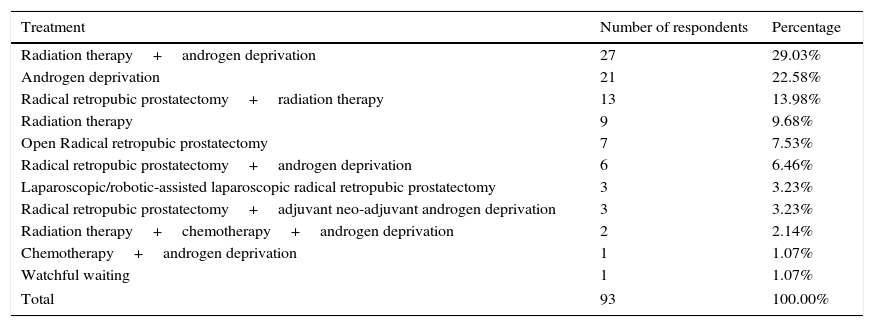

Question 6: treatment in patients with high-risk prostate cancer with extraprostatic extensionTable 4 shows our findings. Fifty-two of the participants used 2 or more treatment modalities and 40 out of 93 participants included radiation therapy as treatment for this group of patients. Only 10.75% of the contestants decided upon radical prostatectomy as monotherapy in the management of these patients (Table 4). However, we have to acknowledge the likelihood of future multimodality therapy in high-risk cancer patients initially treated with monotherapy.7 The use of radical prostatectomy as monotherapy has currently decreased due to the recognition that prostatectomy alone is insufficient.15 Recent trials have demonstrated that the use of neo-adjuvant androgen deprivation before prostatectomy does not provide benefit compared with surgery alone.25 On the other hand, surgery is now being performed as the first stage of multimodality therapy. For example, the combination of radical prostatectomy (RP) plus early adjuvant hormone therapy has been shown to achieve a 10-year cancer-specific survival of 80%.26 It is possible that surgery will become the cornerstone of integrated treatment, in the form of cytoreductive therapy and its potential combination with adjuvant radiotherapy. If they are carried out the other way around, they will not provide the same benefit and will lower the chances of salvage surgery, because of greater technical demands and risk. Furthermore, adjuvant radiotherapy focuses on a smaller area when compared with primary radiotherapy.

Treatment in patients with high-risk prostate cancer with extraprostatic extension.

| Treatment | Number of respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Radiation therapy+androgen deprivation | 27 | 29.03% |

| Androgen deprivation | 21 | 22.58% |

| Radical retropubic prostatectomy+radiation therapy | 13 | 13.98% |

| Radiation therapy | 9 | 9.68% |

| Open Radical retropubic prostatectomy | 7 | 7.53% |

| Radical retropubic prostatectomy+androgen deprivation | 6 | 6.46% |

| Laparoscopic/robotic-assisted laparoscopic radical retropubic prostatectomy | 3 | 3.23% |

| Radical retropubic prostatectomy+adjuvant neo-adjuvant androgen deprivation | 3 | 3.23% |

| Radiation therapy+chemotherapy+androgen deprivation | 2 | 2.14% |

| Chemotherapy+androgen deprivation | 1 | 1.07% |

| Watchful waiting | 1 | 1.07% |

| Total | 93 | 100.00% |

Nine participants utilized radiotherapy as monotherapy, but current medical evidence suggests that this sort of therapy alone is inefficient and that results are more effective when combined with androgen deprivation therapy (ADT).7 In patients who are not candidates for radical treatment, EAU guidelines indicate that early androgen deprivation may improve survival, using surgical castration or hormone therapy, mainly with luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone agonists or antagonists, which are all deemed to be equally effective.7

In summary, the current tendency for treatment of high-risk patients with extraprostatic extension is multimodality therapy with surgery as the initial step of this treatment.

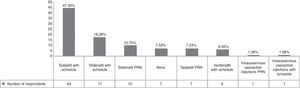

Question 7: first-line treatment in patients with metastatic prostate cancerThe National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) establishes that ADT is the gold standard for men with metastatic prostate cancer.27 According to EUA guidelines on the multiple therapeutic approaches for ADT, the gold standard is surgical castration, such as bilateral orchiectomy.7 Few surveyed urologists preferred surgical management and the majority of the urologists used hormone therapy (Table 5). Surgical management is the gold standard, but the luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonists and antagonists are equally effective.27 Consequently, the tendency is for surgical castration to be used less frequently. Antiandrogen monotherapy is not considered as effective as LHRH blockade or surgical castration by most guidelines. From our sample, only 3 physicians used antiandrogen monotherapy. Nowadays, LHRH agonists are the main form of ADT used in conjunction with early antiandrogens to prevent the flare effect; in our population this was the most common therapy. One of the main problems is the cost-effectiveness of long-term hormone therapy. According to a previous report, medical castration with combined androgen blockade is the least economically attractive strategy, when compared with surgical castration.28 We consider that the use of orchiectomy in Mexico is below the expected frequency, possibly due to the conditions of the Mexican economy. Surgical castration is a potential option that should be contemplated.

First-line treatment in patients with metastatic prostate cancer.

| Treatment | Number of respondents | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Complete androgen blockade (central+peripheral) | 52 | 60.47% |

| Central androgen blockade using luteinizing hormone-releasing agonist hormone | 16 | 18.60% |

| Central androgen blockade using luteinizing hormone-releasing antagonist hormone | 9 | 10.47% |

| Bilateral orchiectomy | 6 | 6.98% |

| Peripheral androgen blockade | 3 | 3.48% |

| Total | 86 | 100.00% |

There are numerous opportunities for improvement in regard to the clinical practice of urologists that manage patients with prostate cancer in Mexico. Many urologists follow international recommendations, but these are not adjusted to Mexican patients and their environment, as is the case with antibiotic prophylaxis or metastatic disease management. Given that prostate cancer is a prevalent malignant disease, attention must be guided towards the particular needs of our country. In addition, physicians must constantly update their knowledge to avoid practices that do not benefit the patient, such as an excessive number of cores in first prostate biopsies, over-extensive or limited lymphadenectomy, or incomplete treatment in high-risk prostate cancer patients presenting with extraprostatic extension.

FundingNo financial support was received in relation to this study.

Conflict of interestCIVS: None, JARR: None, GRV: None, ALC: None, RACM: Speaker for Lilly, MSdZ: Speaker for Probiomed, Lilly, and GSK.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this investigation.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.