An emendation of the generic description of Scleroderma is proposed to consider the membranaceous veil like, or granulose patches, both on the base of the globose basidiome or on the upper part of the stipe, formed by the growth of the basidiome, which breaks the exoperidium. Veligaster previously segregated by this character, is a synonym. Guzmán's classification of the genus in 3 sections is followed, however due to the change of the type of the genus for S. verrucosum, Sect. Aculeatispora is now a synonym of Sect. Scleroderma, and S. citrinum that was in Sect. Scleroderma is now in a new section named Reticulatae. A review of the 21 Mexican species of Scleroderma is presented, 14 of these are accepted. The most common species in the country is S. nitidum in the tropical and subtropical forests. New localities from Mexico and foreign countries are discussed in S. bermudense, S. bovista, S. citrinum, S. hypogaeum, S. michiganense, S. polyrhizum, and S. pseudostipitatum. On the other hand, it is discussed that S. sinnamariense seems absent in Mexico, because it was confused with S. bermudense.

Se presenta una emendación del género Scleroderma para considerar los parches membranáceos o granulosos en el exoperidio, presentes en la base de la porción globosa del basidioma y en la parte apical del estípite. Éstos se forman por el desgarramiento en el crecimiento del basidioma, pero no habían sido tomados en cuenta antes. Veligaster, previamente segregado por este carácter es sinónimo. Se sigue la clasificación en secciones propuesta por Guzmán en 1970, pero debido al cambio de la especie tipo del género, ahora S. verrucosum, la sec. Aculeatispora es sinónima de la sec. Scleroderma, y S. citrinum, antes en la sec. Scleroderma, se acomoda en la sección ahora nombrada Reticulatae. Se revisaron las 21 especies de Scleroderma citadas de México, de las que se reconocen 14. La especie más común en el país es S. nitidum, que se desarrolla en bosques tropicales y subtropicales. Se registran S. bermudense, S. bovista, S. citrinum, S. hypogaeum, S. michiganense, S. polyrhizum y S. pseudostipitatum de nuevas localidades, incluso del extranjero. Se discute que S. sinnamariense parece ausente en México, debido a que los registros de ella corresponden a S. bermudense.

Since Guzmán (1970)'s world monograph on the genus Scleroderma, few new observations have been published in Mexico, except the review by Guzmán-Dávalos and Guzmán (1985) on the species of Jalisco, where it was discussed S. bovista and S. polyrhizum. Later, Guzmán and Tapia (1995) described S. mexicana and recorded S. pseudostipitatum, both as Veligaster. Cortés-Pérez (2011) reviewed the genus in Veracruz. Moreover, there are several records on previously known species, many did not checked yet, as those of Herrera et al. (1989, 2005), Pérez-Silva et al. (1992, 1994), Esqueda-Valle et al. (1995, 2000, 2011), Nava-Mora and Valenzuela (1997), Díaz-Barriga et al. (1998), Quiñones-Martínez and Garza-Ocaflas (2003), Herrera and Pérez-Silva (2004), Pardavé-Díaz et al. (2006), Moreno et al. (2010), and Canseco-Zorrilla (2011), among others.

Important works on Scleroderma after Guzmán (1970)'s monograph were reviewed, as those from North, Central and South America, Africa, Europe and Asia by Demoulin and Malengon (1970), Demoulin and Dring (1971, 1975), Jeppson (1979, 1986, 1998), Beaton and Weste (1982), Calonge (1982, 1998), Kobayasi (1986), Rifai (1987), Coccia et al. (1990), Sims et al. (1995, 1997, 1999), Grgurinovic (1997), Guzmán and Ovrebo (2000), Macchione (2000), Kasuya et al. (2002), Poumart (2003), Guzmán et al. (2004), Watling and Sims (2004), Calonge et al. (1997, 2005), Liu et al. (2005), Gurgel et al. (2008), Guzmán and Ramírez-Guillén (2010), Cortez et al. (2011), Guzmán and Piepenbring (2011), Alfredo et al. (2012), and Nouhra et al. (2012). New species described in those papers are: S. congolense Demoulin et Dring and S. schmitzii Demoulin et Dring from Africa; S. cyaneoperidiatum Watling et K.P. Sims, S. hakkodense Kobayasi, and S. xanthochroum Watling et K.P. Sims from Asia; S. mayama Grgur., and S. paradoxum G.W. Beaton from Australia; S. meridionale Demoulin et Malengon from Mediterranean area; S. franceschii Macchione, and S. septentrionale Jeppson from Europa; and S. minutispora Baseia, Alfredo et Cortez from Brazil, and S. patagonicum Nouhra et Hernández-Caffot from Argentina. The present paper can be considered an introduction to the second edition of the monograph on the genus Scleroderma.

Materials and methodsMicroscopic observations were made from hand sections of the dry basidiome, mounted in 5% aqueous KOH solution, plain or mixed with 1% Congo red solution, after the material being rehydrated in 96% alcohol. It was also used cotton blue in lactophenol; sometimes the material was boiled gently to prevent cells covering the basidiospores, which make difficult the study. In the size of the basidiospores, spines and reticulum are included. Exceptional dimensions are indicated in parenthesis and super-exceptional cases in a second parenthesis. In the descriptions or comments of the species, we avoid the hyphae of the peridium, because they lack in general of taxonomic importance, except in some cases. More than 300 specimens were macro- and microscopically studied, also several from other countries. For limitations on the available space, only some representative herbarium specimens are mentioned.

DescriptionsScleroderma vs. Veligaster. Guzmán (1969) described this latter based on Scleroderma columnare Berk. and Broome from Ceylon (today Sri Lanka), Java and Singapore, and on S. leptopodium Pat. et Har. from Central Africa. The taxonomic feature to distinguish Veligaster was the veil-like patches on the exoperidium, both on the upper part of the stipe, and on the base of the globose basidiome. These patches are formed by the growth of the basidiome, which breaks the exoperidium, and lyses the hyphae. When dry, these patches turn blackish and granulose and are lost in some species. Guzmán and Tapia (1995) described V. mexicanus Guzmán et Tapia and V. singaporensis Guzmán et Tapia. Also they considered Scleroderma pseudostipitatum and S. nitidum as Veligaster. Cunningham (1942) presented S. verrucosum in the plate XV, fig. 2, with 2 basidiomata, which have a well developed stipe, covered in the upper part with a conspicuous veil, but he did not describe it. It seems that Cunningham' fungus is really S. columnare. Studying the authors Mexican specimens of S. citrinum and S. verrucosum, they found the veil-like blackish patches on the base of the sessile, globose basidiome, also on the upper part of the lacunose pseudostipe and on the globose apex. They concluded that in all the species of the genus these patches are formed by the growth of the basidiome. Then these patches have not taxonomic value. In this way Veligaster is a synonym of Scleroderma. Recent DNA studies (e.g. Sims et al., 1999; Binder and Bresinsky, 2002; Watling, 2006; Louzan et al., 2007) showed that Veligaster columnaris is a synonym of Scleroderma columnare.

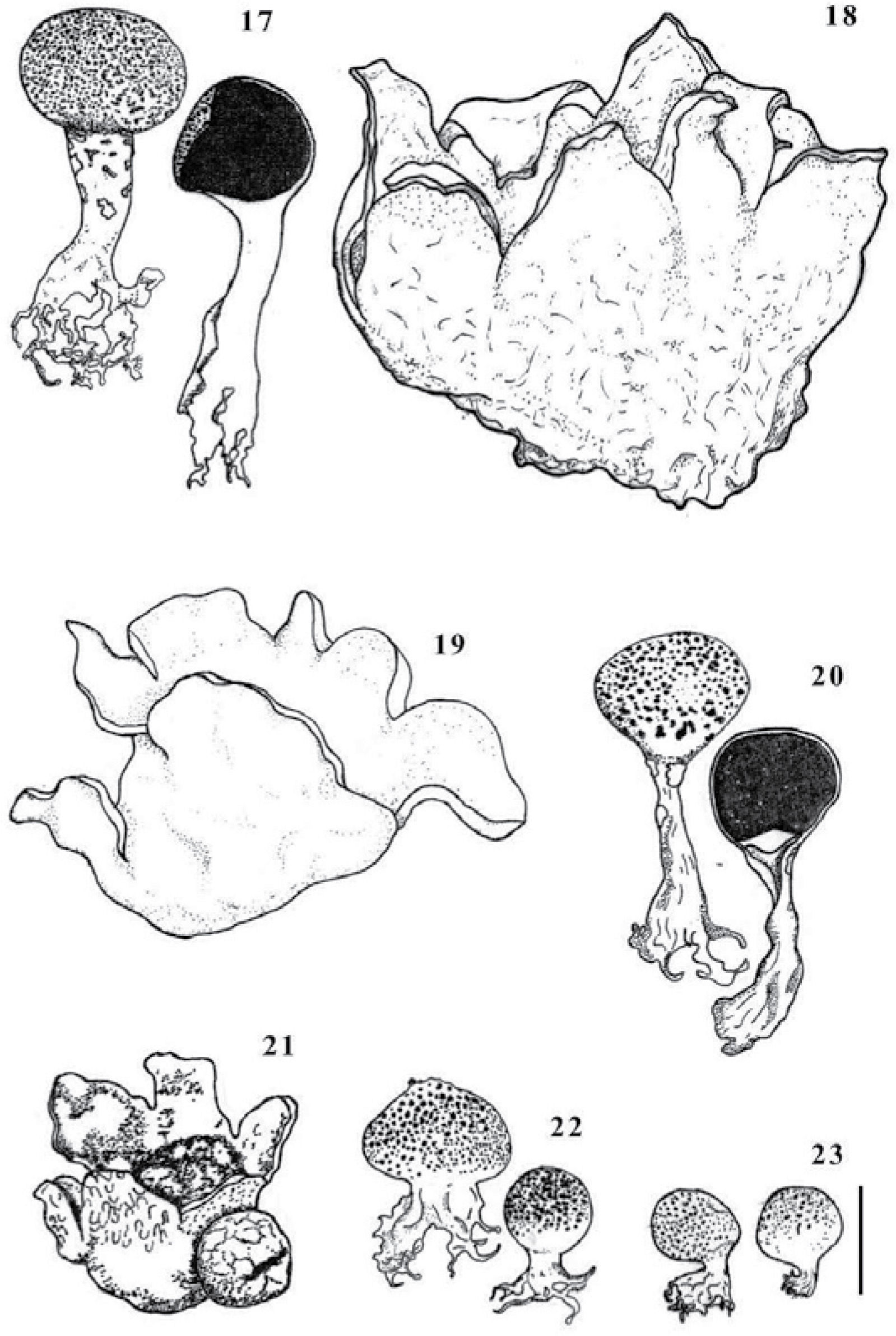

Basidiomata of several species of Scleroderma. 17, S. nitidum (Cortés-Pérez 278). 18–19, S. polyrhizum (18, Guzmán 30516-A; 19, Guzmán 32145-A). 20, S. pseudostipitatum (Gándara 1345). 21, S. texense (Cortés-Pérez 674). 22–23, S. verrucosum (22, Cortés-Pérez 266; 23, Cortés-Pérez 276). Scale= 20mm.

Scleroderma Pers. emend Guzmán emend nov.

Scleroderma Pers., Syn. Meth. Fung. 1: xiv, 150, 1801.

= Pompholyx Corda, in Sturm., Deutschl. Fl. (Pilze Deutschl.) III, 3(12): 51, 1834.

= Phlyctospora Corda, in Sturm., Deutschl. Fl. (Pilze Deutschl.) III, 7(19-20): 51, 1841.

= Sclerangium Lév., Ann Sci. Nat. Bot., sér. 3,9:130, 1848.

= Caloderma Petri, Malpighia 14: 136, 1900.

= Veligaster Guzmán, Mycologia 61: 1117, 1969.

Generitypus: S. verrucosum (Bull.) Pers. (!).

After the synonymy of Veligaster with Scleroderma, which was based on the veil-like patches on the peridium which did not considered in the concept of Scleroderma, it is necessary to do an emendation, as follow. Those words in italics are new features or not clearly described before in the concept of the genus.

Basidiome leathery to very hard when dry, globose, subglobose, pyriform, sessile, pseudostipitate or with a well developed stipe, with a large basal compact mass of mycelium. Exoperidium thin or thick, dry, smooth, cracked, scaly or cover by small or large scales, frequently with membranaceous veil-like or patches on the base of the globose basidiome or in the upper part of the stipe, also sometimes in the apex of the basidiome, formed by the basidiome growth which lacerates and lysis the hyphae. Endoperidium thin, with a membrane covering the gleba. Both exo-and endoperidium frequently rufescent. Gleba subfleshy to leathery, compact, finally dusty, white, soon purple or dark grayish-brown or reddish-brown, at first with tramal plates, then with thin whitish or yellowish filaments. Dehiscence by cracking the apical part of the basidiome, or through an irregular lacerated apical pore or stellated by tearing off all the peridium, in this latter case all the gleba is lost. Hymenium not developed. Capillitium absent. Basidiospores globose, thick-walled, yellowish-brown, echinulated, subreticulated or reticulated, when immature and subglobose, smooth, with a visible apiculus. Ornamentation meanly due to the nutrient cells (trophocysts) that cover all the surface of the young basidiospores, helping in its development; when the spores mature, these cells leave their walls on the surface of the spore (fig. 31). Basidia 4-6 (−8) spored, pyriform, sometimes claviform, thin or thick-walled, hyaline, discharging early the basidiospores in an immature stage. Odor and taste in general strong like rubber. Habitat on soil, rarely on rotten wood, or on ferns stipes, epigeous or hypogeous, ectomycorrhizic.

Temperate, subtropical and tropical species.

Review of the taxonomic features in Scleroderma. Both macro-and microscopic features are important in the taxonomy of Scleroderma, although the latter, i.e. the basidiospores ornamentation and the clamp connections are the base of its classification, and the basidiospores structure and size are the key for the species determination, together with the peridium structure. Dehiscence type, presence of stipe, and peridium color are also important macroscopic features. It seems that the thickness of the basidium wall is also relevant, as well as its form, i.g. S. texense. Sometimes the wide of the hyphae of both endoor exoperidium, and the thickness of their wall seem important. Presence or absence of clamps connections are very important. Chemical reactions on the peridium seem without taxonomic value, KOH stains brownish, brown, orange or reddish-brown, in a wide range of variation.

Classification of the genus and considered species. Based in the structure of the surface of the basidiospores, as well in the presence or absence of clamp connections, Scleroderma was divided by Guzmán (1967, 1970) in 3 sections: Aculeatispora Guzmán, with echinulated basidiospores and without clamps; Sclerangium (Lév.) Guzmán, with subreticulated basidiospores and common clamp connections; and Sect. Scleroderma with reticulated basidiospores and clamps. This classification had been accepted for several specialists, e.g. Phosri et al. (2009) through a phylogenetic study with molecular data stated that Guzmán's classification is natural. However, the names of 2 sections need to be changed, as stated above, because now S. verrucosum is the type of the genus, then it belongs to Sect. Scleroderma instead of Aculeatispora, and Sect. Scleroderma sensu Guzmán requires another name. We proposed here the new name Reticulatae Guzmán.

It is interesting to know, that Van Bambeke (1906) was the first specialist who studied the structure of the basidiospores in Scleroderma. He divided the genus in 2 groups, the reticulated spores group with S. aurantium (L.) Pers. and S. bovista, and that of the echinated spores without reticulum, with S. cepa and S. verrucosum. Regarding the considered species in the present paper, it is curious that S. sinnamariense Mont. that was reported from Mexico by Guzmán (1983, 2003) and Canseco-Zorrilla (2011) from tropical forests, seems absent. It was confused with S. bermudense. The same with the record of S. stellatum (Guzmán, 1983) which belongs to S. bermudense.

Key to the considered species.

- 1a.

Basidiospores echinulated, neither subreticulated, nor reticulated.

Withoutclampconnections(Sect.Scleroderma)……2

- 1b.

Basidiospores subreticulated or reticulated. Clamp connections present(Sects. SclerangiumandReticulatae)……8

- 2a.

Exoperidium smoothto cracked, uniformly colored……3

- 2b.

Exoperidium warty with small dark brown scales……5

- 3a.

Basidiome stipitate. Peridium thin, velvety. Basidiospores (7-) 8–10 (−11) μm diam. Tropical species……S. mexicana

- 3b.

Basidiome sessile. Peridium thin or thick, not velvety.

Temperateorsubtropicalspecies……4

- 4a.

Basidiospores (10−) 13–17 (−18) (−19) μm diam. Dehiscense by cracking the apical peridium or substelliform. Temperate species……S. albidum

- 4b.

Basidiospores (7−) 8–13 (−14) μm diam. Dehiscense stelliform orby cracking the apical peridium. Temperate species……S. cepa

- 5a.

Basidiome sessile or shortly stipitate. Basidiospores (9−) 10–15 (−18) μm diam. Temperate species……S. areolatum

- 5b.

Basidiome pseudo- or stipitate……6

- 6a.

Basidiome pseudostipitate. Basidiospores (8−) 9–12 (−14) μm diam. Temperate or subtropical species……S. verrucosum

- 6b.

Basidiome sessile or stipitate. Subtropical or tropical species……7

- 7a.

Basidiospores (6−) 7-11 (−12) μm diam. Subtropical species……S. nitidum

- 7b.

Basidiospores (8.5−) 10-14 (−15) μm diam. Tropical and subtropical species……S. pseudostipitatum

- 8a.

Basidiospores subreticulated, reticulum thin and incomplete. Dehiscense stelliforme (Sect. Sclerangium)……9

- 8b.

Basidiospores reticulated, reticulum thick, sometimes not uniform. Dehiscence by cracking the apical peridium or substelliform (Sect. Reticulatae)……11

- 9a.

Small basidiome, 15–25mm diam. Basidiospores (5−) 6–9 μm diam. In sand dunes, associate with Coccoloba, in the tropics……S. bermudense

- 9b.

Large basidiome, 60–100mm diam. Basidiospores (6−) 7–11 (−12) μm diam. On clay or sandy soils, temperate, subtropical or tropical species……10

- 10a.

Peridium rough to cracked, whitish to grayish-yellow……S. polyrhizum

- 10b.

Peridium strongly scaly, whitish to yellowish or some orangish, with thick and folded scales……S. texense

- 11a.

Basidiospores up to 22 (−26) or 23 (−30) μm diam. Hypogeous or epigeous basidiomata……12

- 11b.

Basidiospores up to 14 (−17) μm diam. Epigeous basidiomata……13

- 12a.

Exoperidium smooth, slightly cracked or subscaly. Basidiospores (15−) (17−) 20-23 (−26) (−30) μm diam. Hypogeous or subhypogeous……S. hypogeoum

- 12b.

Exoperidium scaly or verrucose. Basidiospores (13−) 15-22 (−23) μmdiam. Mainly epigeous……S. michiganense

- 13a.

Exoperidium smooth to finely warty, whitish or yellowish-brown, with minute dark scales. Basidiospores with a uniform and thick reticulum……S. bovista

- 13b.

Exoperidium thick, coarsely scaly, scales in rosette in the apex or on the sides, yellowish to orange-yellowish. Basidiospores with a not uniform but thick reticulum……S. citrinum

Scleroderma albidum Pat. et Trab. emend. Guzmán, Darwiniana 16: 295, 1970.

= Scleroderma albidum Pat. et Trab., Bull. Soc. Mycol. Fr. 15: 57, 1899.

= Sclerodermaflavidum Ellis et Eveh. f. macrosporum G. Cunn., Trans. Proc. New Zeal. Inst. 62: 117, 1931.

= Scleroderma reae Guzmán, Ciencia (Méx.) 25: 200, 1967 (!).

= Scleroderma laeve Lloyd emend. Guzmán, Darwiniana 16: 301, 1970 (!).

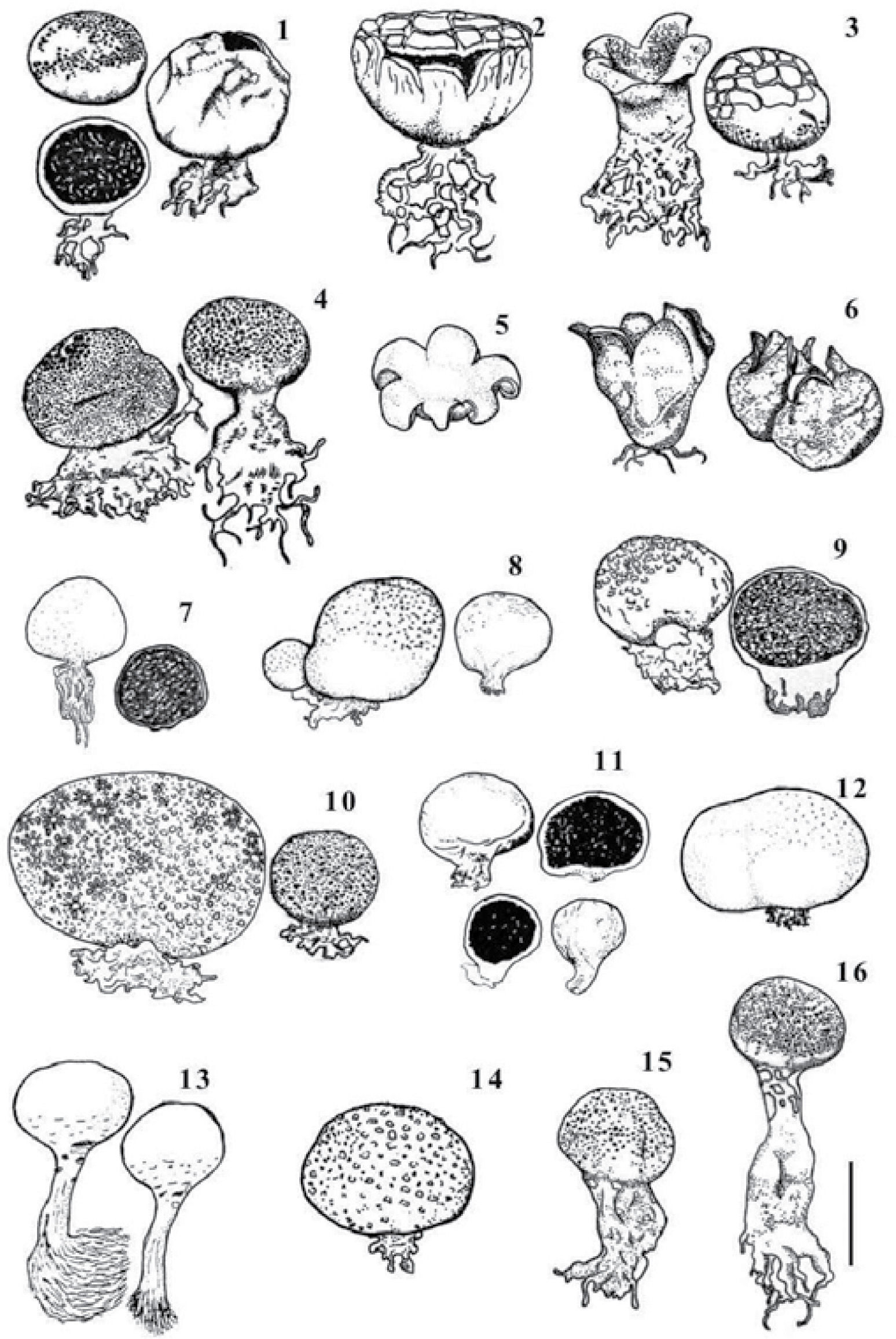

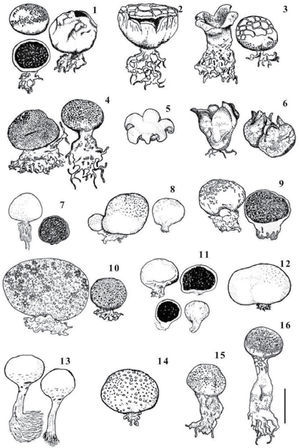

Basidiomata of several species of Scleroderma. 1–3, S. albidum (1, Cortés Pérez 285; 2, Cortés Pérez 300; 3, Cortés-Pérez et Arias-Vergara 126). 4, S. areolatum (Cortés-Pérez 305). 5–6, S. bermudense (5, Guzmán 34475; 6, Guzmán 35528). 7–8, S. bovista (7, Rivera-Camacho s. n.; 8, Guzmán-Dávalos 9410). 9, S. cepa (Escalona 138). 10, S. citrinum (Cortés-Pérez 303). 11–12, S. hypogaeum (11, Guzmán 38484, 12, Guzmán 30516–B). 13, S. mexicana (holotype). 14, S. michiganensis (Ambriz s.n.). 15–16, S. nitidum (15, Cortés-Pérez 12; 16, Cortés-Pérez 391). Scale= 20mm.

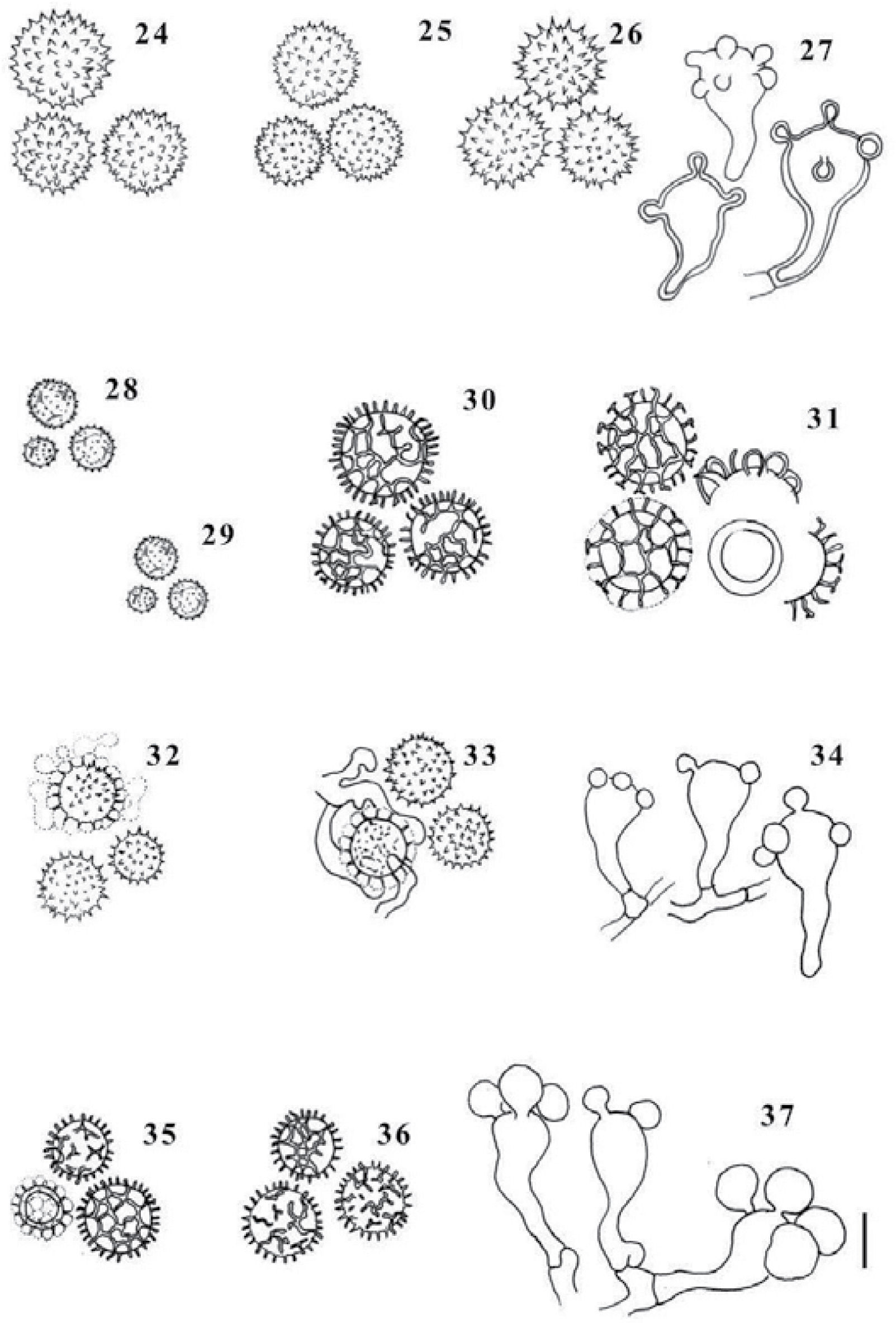

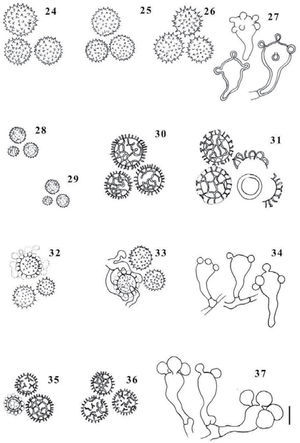

Basidiospores and basidia of Scleroderma. 24–25, S. albidum (24, Murrieta-Armenta 18; 25, Cortés-Pérez 300). 26–27, S. areolatum (Cortés-Pérez 412). 28–29, S. bermudense (28, Guzmán 35528; 29, Guzmán 34475). 30–31, S. bovista (30, Rivera-Camacho s.n.; 31, type of Phlyctophora fusca). 32–34, S. cepa (32, Escalona 138; 33–34, Cortés-Pérez 313). 35–37, S. citrinum (35, Cortés-Pérez 171; 36, Cortés-Pérez 172; 37, Cortés-Pérez 331). Scale= 10μm.

Basidiome (10−) 15–50mm diam., globose or pyriform, sessile or shortly stipitate. Peridium thick, whitish to pale yellowish-brown, smooth to irregularly cracked on the apex. Dehiscence by irregular cracking on the apical peridium or substelliform. Gleba whitish to dark reddish-brown, with whitish and yellowish filaments. Context rubescent. Taste and odor like something rubber. Basidiospores (10−) 13-17 (−18) (−19) μm diam., echinulated, spines 1-2 (−3) μm high. Hyphae of endoperidium 2-17 μm wide, thin- to thick-walled. Oleiferous hyphae present in exoperidium. Clamp connections absent.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious on soil, mainly in parks or Eucalyptus plantations or disturbed Pinus-Quercus forests. See table 1 for its distributions in Mexico.

The collections from Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Durango are the first records from these regions.

Selected studied specimens. Baja California, region of Ensenada, 5km E of Agua Viva, Dec. 10, 1983, Ayala 227 (XAL). Coahuila, Monclova Municipality, Oct. 21, 1970, Guzmán 17421 (XAL). Chihuahua, Barranca del Cobre, S of Creel, Aug. 18-19, 2004, Guzmán 36028 (XAL). Durango, Biosphere Reserve La Michilia, near the Biological Station, Aug. 20, 1982, Rodríguez 647 (XAL). Jalisco, Tequila Hill, July 30, 1983, Rodríguez 143 (IBUG). Michoacán, Zitácuaro road to Morelia, near Mil Cumbres, Aug. 18, 1989, Guzmán 29498 (XAL). Veracruz, Xalapa, Zona Universitaria, July 30, 2010, Cortés-Pérez 285 (XAL).

Remarks. This species was described by Patouillard and Trabut from Algeria (Patouillard, 1899). They described basidiospores 10–13μm diam., but the type (at FH) presents basidiospores 10.5–17.5μm diam. It seems that S. albidum is a southern hemispheric species, linked with Eucalyptus. Cortez et al. (2011) reported this species and S. laeve as common in Brazil below Eucalyptus. Here, we considered S. laeve and S. reae as synonyms because new observations on these fungi showed that there is not difference between them and S. albidum for the great variation of the basidiospores size, as well as the form of the basidiome.

Scleroderma areolatum Ehrenb., Sylv. Mycol. Berol. (Berlin) 15: 27, 1818.

= Scleroderma lycoperdoides Schwein., Schr. Naturf. Ges. Leipzig 1: 61, 1822.

= Scleroderma verrucosum s. Guzmán, Ciencia (Méx.) 25: 199, 1967, non Guzmán, 1970.

Basidiome 15–30mm diam., globose or pyriform, sessile or shortly pseudostipitate. Peridium thin, membranous when mature, yellowish-brown, with distinct inherent, small, very irregularly in form, dark brown or blackish scales. Dehiscence through an irregular, lacerate apical pore. Gleba whitish to dark reddish-brown. Context strongly rubescent. Taste and odor like rubber. Basidiospores (9−) 10–15 (−18)μm diam., echinulated, spines 1–3 (−4)μm high. Basidia 16–32×10–14μm, 4–6 sterigmata, pyriform, hyaline. Clamp connections absent.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious, caespitose or fasciculated on soil, epigeous, in Pinus-Quercus forests. See in table 1 the distribution in Mexico.

Selected studied specimens. Chiapas, Tapachula region, near of Rancho Nuevo, Sept. 14, 1989, Guzmán 29563 (XAL). Chihuahua, Barranca del Cobre, near Hotel Posada Mirador, Aug. 20–23, 2004, Guzmán 36031 (XAL). Jalisco, Zapopan Municipality, Las Agujas, Instituto de Botánica gardens, Aug. 20, 1084, Guzmán-Dávalos 1691 (IBUG); Santa Lucía road to El Guaje, Sept. 8, 2004, Sánchez-Jácome 1055 (XAL). Tlaxcala, Huilapan, Sept. 2007, Bonito 32476 (XAL). Veracruz, W of Xico, Cruz Blanca road to Rusia, Sept. 5, 2010, Cortés-Pérez 412 (XAL).

Remarks. Scleroderma areolatum is close to S. verrucosum, only the size of the basidiospores separates both species.

Scleroderma bermudense Coker, Mycologia 31: 624, 1939.

= Sclerangium bermudense (Coker) D.A. Reid, Kew Bull. 31: 681, 1977.

= Sclerangium bermudense var. trinitense D.A. Reid, Kew Bull. 31: 681, 1977.

Basidiome 15–20mm diam., reachingupto 30mm diam. in dehiscence stage, globose, sessile. Peridium thick, up to 2mm, whitish to yellowish, yellow or brownish, stained violaceous-red when cut, covered by a loosely woven pale outer coat mixed with sand. Dehiscense stelliform, with 4–6 branches, which in mature stage remains only as a plane star, chocolate-brown or yellow, thick peridium. Gleba grayish or reddish-gray. Taste and odor not reported. Basidiospores (5−) 6–9μm diam., subreticulated, reticulum no so well formed, spines and reticulum 0.5−1.5μm high. Clamp connections present.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious and hypogeous on sand, epigeous in the dehiscence, associate with Coccoloba, mainly C. uvifera (L.) L. Common in the Caribbean region including Mexico, but also in Pacific Ocean coasts and Gulf of Mexico.

Selected studied specimens. Guerrero, Ixtapa Zihuatanejo, Jun. 16, 1999, Guzmán 32973. Acapulco, Sept. 26, 2003, Guzmán 35564 (XAL). Quintana Roo, N of Leona Vicario, Ecological Reserve El Edén, Nov. 1, 2000, Guzmán 34475 (XAL). Veracruz, near highway Veracruz to Nautla, Biological Station of La Mancha, Aug. 20, 2003, Guzmán 35528 (XAL). Yucatán, Dzilam to Telchac, near Chabian, Oct. 28, 1984, Guzmán 24742 (XAL).

Remarks. Scleroderma bermudense was described by Coker (1939) from Bermuda Islands below Coccoloba uvifera. Reid (1977) considered this fungus as Sclerangium bermudensis and also described S. bermudense var. trinitensis from Trinidad Island. Guzmán (1970) considered Scleroderma bermudense as synonym of S. stellatum, but later, Guzmán et al. (2004) stated that S. stellatum from Brazil was an independent taxon, because it presents echinulated peridium, and for this reason was also known as Caloderma echinatum [= Scleroderma echinatum]. See also table 1.

Scleroderma bovista Fr., Syst. Mycol. 3: 48, 1829.

= Scleroderma vulgare var. macrorrhizon Fr., Syst. Mycol. 3: 47, 1829.

= Scleroderma macrorrhizon Wallr., Fl. Crypt. Germ., Nürnberg 2: 404, 1833.

= Phlyctospora fusca Corda, in Sturm, Deutschl. Fl. (Pilze Deutschl.) III, 7(19–20):51, 1841.

= Scleroderma fuscum (Corda) E. Fisch. in Engl. et Prantl, Nat. Pflanzenfam. I., Ab. 1**: 336, 1900 (!).

= Scleroderma lycoperdoides var. reticulatum Coker et Couch, Gasteromycetes East. U.S. et Canada, p. 170, 1928.

= Scleroderma verrucosum subsp. bovista (Fr.) šebek, Sydowia 7: 177, 1953.

= Scleroderma verrucosum var. fascirhizum šebek, Sydowia 7: 179, 1953.

= Scleroderma citrinum var. reticulatum (Coker et Couch) Guzmán, Ciencia (Méx.) 25: 204, 1967.

Basidiome 10–45mm diam., globose or subpiriform, sessile or with a short pseudostipe or a short fasciculated base formed by compact mycelium. Peridium thick, whitish or pale yellowish-brown to dark brown, smooth to something verrucose with dark minute scales or cracked. Dehiscence through an irregular break of the apical part. Gleba white to dark reddish-brown, with yellowish filaments. Context rubescent. Taste and odor like rubber. Basidiospores (10−) 11–13 (−15) (−18)μm, reticulated, reticulum 1–3 (−4)μm high, thick, some spines curved as remains of the nutritive cells (fig. 31). Clamp connections present.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious on soil, in Pinus and Quercus forests, frequently in grasslands. See its distribution in table 1.

Selected studied specimens. Jalisco, Zapopan Municipality, Zapopan, Hospital ángel Leaño, Sept. 13, 1992, Fierros 13 (IBUG); Santa Lucía road to El Guaje, Sept. 8, 2004, Guzmán-Dávalos 9410 (IBUG); La Primavera, Sept. 16, 1989, Ayala 5 (IBUG); Ixtlahuatlán del Río, Los Trejos, Nov. 24, 1980, Rivera-Camacho s.n. (IBUG, XAL); Volcán de Tequila, Jul. 21, 2001, Ponce 10 (IBUG).

Remarks. Scleroderma bovista is an European and North American fungus, very rare in Mexico. It had been described in different ways, e.g. Coker and Couch (1928) reported the fungus s. Hollos, and described as S. lycoperdoides var. reticulatum, which is also S. bovista. Coker and Couch (1928) related S. bovista with S. texense, based in a collection from Lloyd. Šebek (1953, 1958) regarded S. bovista as S. verrucosum var. bovista and accepted S. texense and S. columnare as synonyms likewise, both that we consider here as independent species. Scleroderma bovista s. Dissing and Lange (1962) from Africa belongs to S. sinnamariense. Scleroderma fuscum by Fischer (1900) is S. bovista, which was described as Phlyctospora fusca (Corda, 1842). However, Corda's fungus was based in immature basidiomata with basidiospores completely surrounded by nutritive cells, as it was observed through the study of the holotype at K and the isotype at PC. In Mexico, S. bovista was recorded by Frutis and Guzmán (1983) and by Guzmán-Dávalos and Guzmán (1985). The former record was not review in the present paper, but the latter was studied, also other collections from Jalisco. It is curious the few records from Mexico of this fungus. Scleroderma fuscum reported by Guzmán et al. (1997) from Veracruz is S. hypogaeum.

Scleroderma bovista is related with S. macrorrhizon s. Guzmán (1967, 1970), which presents a long, lacunose pseudostipe. Scleroderma macrorrhizon is known as S. meridionale by Demoulin and Malengon (1970), and as S. septentrionale by Jeppson (1998). The former was described from the Mediterranean zone (Demoulin and Malengon, 1970). Later Demoulin (1974) compared S. meridionale with North American collections studied by Smith (1951) and Guzmán (1970) identified as S. macrorrhizon. Demoulin considered those specimens conspecific with S. meridionale, but with the Nordic European pseudostipitated forms as S. bovista. Also Demoulin regarded S. vulgare var. macrorrhizon (Fries, 1829) as S. bovista with pseudostipe. However, S. macrorrhizon by Wallrothio based in the study of the type by Demoulin, has not a real pseudostipe, only a mass of compact mycelium and basidiospores 10–13μm diam., reticulated. This is the typical S. bovista here considered. Concerning the distribution of S. bovista in America, it is interesting that besides the records by Guzmán (1970) from USA (also as S. fuscum), it is know from Central and South America, 2 records from Costa Rica, one by Fries (1829) and other by Calonge et al. (2005). Cortez et al (2011) reported this fungus from Brazil, also as S. fuscum. Furthermore, Guzmán and Ramírez-Guillén (2010) reported S. bovista from Nepal.

Scleroderma cepa Pers., Syn. Meth. Fung. 1: 155, 1801.

= Lycoperdon caepae-facie Vaill., Bot. Par. (Paris): 123, tab. 16:5–6, 1723.

= Scleroderma flavidum Ellis et Everh., J. Mycol. 1(7): 88, 1885.

Basidiome 20–30 (−40)mm diam., but reaching up to 60mm diam. in the dehiscence, globose or subpyrifirm, sessile or pseudostipitated. Exoperidium 1–2mm thick, smooth to coarsely cracked, white, whitish or yellowish to orangish-yellow. Endoperidium whitish to yellowish. Dehiscence stellate, with 6–8 lobes or through an irregular cracker of the upper peridium. Gleba white to brown violaceous. Context frequently rubescent. Odor and taste sometimes like rubber. Basidiospores (7−) 8–13 (−14)μm diam., echinulated, spines 1–2μm high. Basidia 18–25×8.5–10μm, 4 sterigmata, pyriform, hyaline. Hyphae of the endoperidium 3–7 (−10) μm wide, thin-walled. Clamp connections absent.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious, but caespitose and fasciculated on soil, in parks and gardens, also in Quercus, Pinus-Quercus or in mesophytic forests. It is reported here for the first time from Baja California. See in table 1 the known distribution in Mexico.

Selected studied specimens. Baja California, Ensenada road to Ojos Negros, NE of Rancho Agua Viva, Feb. 29, 1984, Ochoa 27 (XAL). Jalisco, NE of Tesistán, La Mesita, Sept. 11, 1998, Rodríguez 2013 (IBUG). Veracruz, highway Xalapa-Veracruz, near El Lencero, Jun. 13, 2003, Escalona 138 (XAL).

Remarks. This is a common European and North American species, known also from Australia (Cunningham, 1942). Its synonymy with S. flavidum was established by Guzmán (1970). However, Migliozzi and Coccia (1988), and Coccia et al. (1990) claimed that S. cepa is an independent species. They based their position in that in S. cepa the basidiome is sessile and the dehiscence is not stelliform, besides the endoperidium presents narrow hyphae, versus S. flavidum which presents pseudostipitated forms, with stelliform dehiscence, and their hyphae of the endoperidium are thicker. Nevertheless, it seems that the S. flavidum they studied is really S. albidum for the size of the basidiospores, 12–16μm diam. Calonge and Demoulin (1975), and Poumart (2003) accepted S. flavidum as a synonym of S. cepa. The color figure of Harkonen et al. (2003) and Calonge et al. (1997) as S. verrucosum from Tanzania, belongs to S. cepa, specimens which were study by Guzmán and Ramírez-Cruz in XAL.

Scleroderma citrinum Pers., Syn. Meth. Fung. 1: 153, 1801.

= Scleroderma vulgare Hornem., Syst. Mycol. (Lundae) 3: 46, 1829.

= Pompholyx sapidum Corda, in Sturm, Deut. Crypt. Fl. 10–20: 47, 1841.

Basidiome (20−) 40–80 (−100)mm diam., globose to ovoid, often apically flattened, sessile or shortly substipitate, with a compact mycelial base. Peridium 2–5mm thick, tough, yellowish-brown to pale orangish-yellow, coarsely scaly, the scales frequently in rosette on the upper part or on the sides, also imbricate and squarrose on the sides, the exoperodium in the base of the basidiome and in the upper part of the pseudostipe breaks in submembranaceous or collapsed fragments, like patches, concolor to blackish, due to the lysing of the hyphae. Endoperidium whitish to yellowish, rubescent when cut. Dehiscence through an irregular apical breaking or substelliform, finishing as an irregular cup-like fruit body. Gleba white to dark vinaceous or purplish, compact, then dusty. Taste and odor like rubber. Basidiospores (9−) (10−) 11–14 (–17)μm diam., subreticulated to reticulated, reticulum 1–2.5μm high. Basidia 14–30×7.5–10μm, pyriform, thin-walled, hyaline, 2–4 (−6) sterigmata. Oleiferous hyphae present in both exo- and endoperidium. Clamp connections present.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious or caespitose, epigeous on soil or humus with mosses, sometimes on rotten wood. Common in coniferous forest or in Pinus-Quercus forests. See in table 1 its distribution in Mexico. The collections from Jalisco and Veracruz are the first records from these states.

Selected studied specimens. Jalisco, Tapalpa, Sept. 3,1978, García-Saucedo s.n. (IBUG). Veracruz, Huayacocotla road to Viborillas, SE of Huayacocotla, Sept. 14, 2009, Cortés-Pérez 170, 175; Aug. 6, 2010, Cortés-Pérez 303 (all in XAL).

Remarks. Scleroderma citrinum is one of the most common species in Europe, but infrequent in Mexico.

Scleroderma hypogaeum Zeller, Mycologia 14: 193, 1922.

= Scleroderma arenicola Zeller, Mycologia 39: 295, 1947, non S. arenicola s. Smith (1951).

= ? Scleroderma patagonicum Nouhra et Hernández-Caffot, Mycologia 104: 490, 2012.

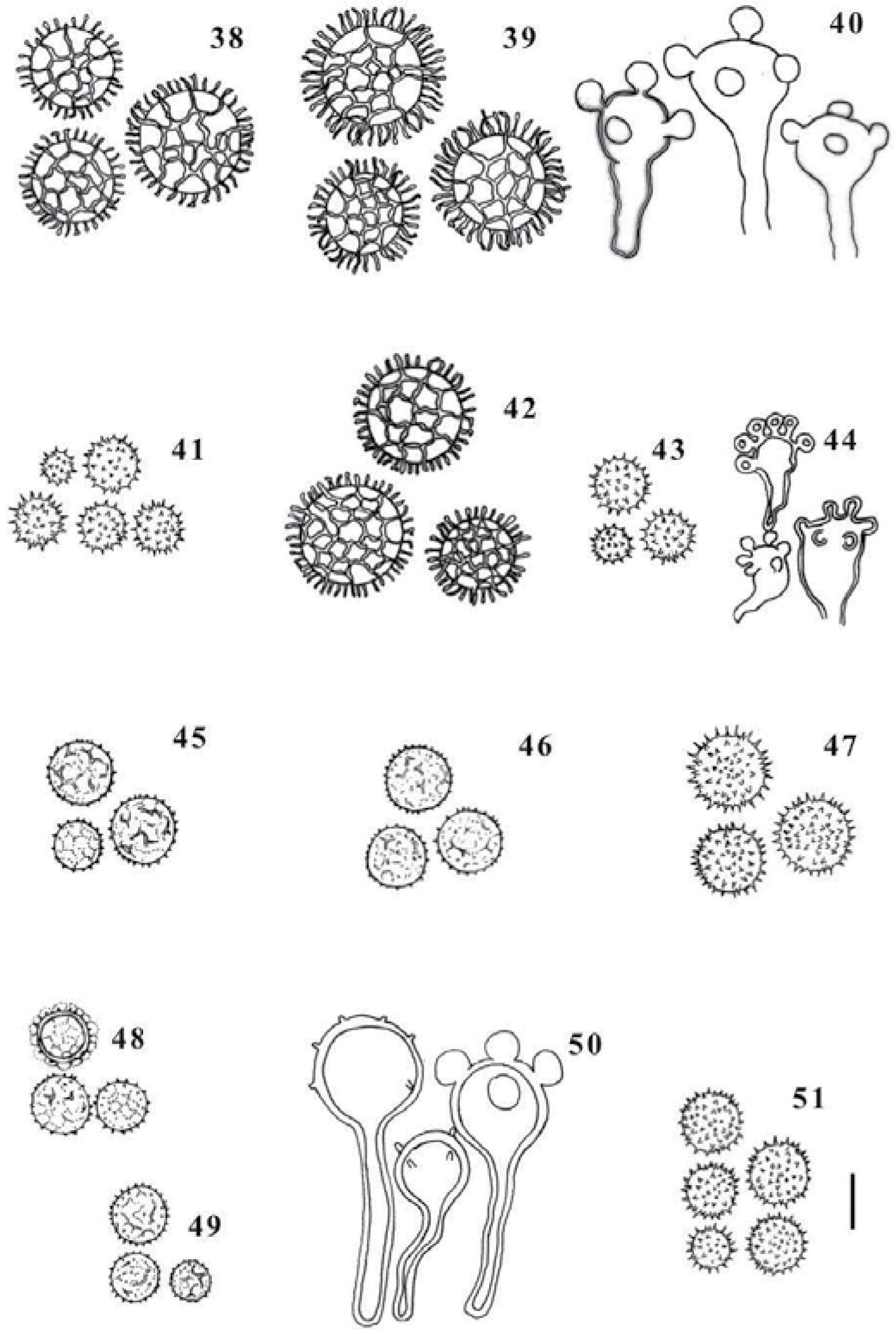

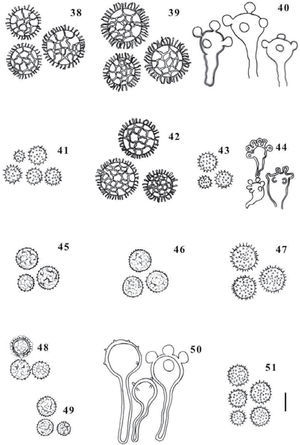

Basidiospores and basidia of Scleroderma. 38–40, S. hypogaeum (38, Guzmán 38504, 39–40, Guzmán 30516-B). 41, S. mexicana (holotype). 42, S. michiganense (Ambriz s.n.). 43–44, S. nitidum (43, Cortés Pérez 391; 44, Guzmán 33885). 45–46, S. polyrhizum (45, Guzmán 24608; 46, Puga s.n.). 47, S. pseudostipitatum (Gándara 1345). 48–50, S. texense (48, Cortés-Pérez 757; 49, Cortés-Pérez 700; 50, Cortés-Pérez 674). 51, S. verrucosum (Guzmán 38132). Scale= 10μm.

Basidiome 15–30mm diam., globose, regular or irregular, sessile or short and irregular pseudostipitate. Peridium 1–3mm thick, smooth or finely subscaly, whitish to pale or dark yellowish-brown. Dehiscence through an irregular apical breaking or substelliform. Gleba whitish to reddish-brown. Context little rubescent. Taste and odor sometimes like rubber. Basidiospores (15−) (17−) 20–23 (−26) (−30)μm diam., reticulated, reticulum thick, reticulum and spines (1.5−) 2–4 (−5)μm high, some spines curved, as remain of the nutritive cells. Basidia 20–30×1–12μm, 4 sterigmata, hyaline. Clamp connections present.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious in soil, hypogeous or subhypogeous, in coniferous forests, mesophytic forests with Quercus, and tropical forests, also probably in Nothofagus forests. See in table 1 its distribution in Mexico. One collection, Guzmán 38589, was found on the stipe of a fern tree (Cyathea) (see in Discussion).

Selected studied specimens. Chiapas, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Botanical Garden F. Miranda, Sept. 17, 1992, Guzmán 30516-B (XAL). Veracruz, old road Xalapa to Coatepec, region of Zoncuantla, July 26, 2005, Guzmán 36332 (XAL); July 2010, Guzmán 38504 (XAL); Oct. 10, 2010, Guzmán 38589 (XAL); July 13, 2012, Guzmán 39174 (XAL).

Remarks. Scleroderma hypogaeum presents the bigger basidiospores in the genus. Its distribution in America is from NW of USA to Central America and probably to Patagonia. Calonge et al. (2005) reported it from Costa Rica. This species was described by Zeller (1922) from Oregon, USA, and later as S. arenicola by the same author (Zeller, 1947). The first record of S. hypogaeum from Mexico was by Herrera (1959) as S. arenicola, and then recorded by Guzmán (1970) as S. hypogaeum. Scleroderma patagonicum (Nouhra et al., 2012) described from Patagonia, Argentina, agrees well with S. hypogaeum in macro- and microscopic features, even in its hypogeous habitat; however, it was described with basidiospores (13−) 19–24 (−28)μm diam. It is necessary to study the type to confirm this synonymy, but it was impossible to get it.

Scleroderma mexicana (Guzmán et Tapia) Guzmán, comb. nov.

= Veligaster mexicanus Guzmán et Tapia, Doc. Mycol. 25(98–100): 186, 1995.

Basidiome 10–26mm diam., globose and stipitated, with the stipe 12–18×2–5mm (all the sizes from dry specimens). Peridium thin, 1mm thick, smooth to somewhat velvety, slightly areolate toward the base of the globose basidiome, pale yellowish to yellowish-brown, with vinaceous color stains. The upper part of the stipe and the base of the globose basidiome breaking into conspicuous dark reddish to blackish veil-like membranaceous patches, formed by lysis of the exoperidium hyphae. Endoperidium whitish. Dehiscence by cracking the apex peridium. Gleba fleshy to dusty, blackish-brown or grayish-violet. Context rubescent. Taste and odor unknown. Basidiospores (7−) 8–10 (−11)μm diam., echinulated, spines 0.8–1.5μm high. Oleiferous hyphae present. Clamp connections absent.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious on soil, in a tropical rain forest. Known only from the type locality.

Selected studied specimens. Chiapas, road Ocozocuautla to Apic-Pac (Malpasado Dam), Laguna Bélgica Ecological Park, Oct. 12, 1992, Palacios et Cabrera 2112 (isotype, XAL).

Remarks. Scleroderma mexicana is close related with S. columnare from Malaysia, but differs in the size of the basidiospores, (8−) 10–12 (−13)μm, with spines 1–4μm high in that species (Guzmán, 1969). Also it is close to S. pseudostipitatum, even in the basidiospores size, but that presents the exoperidium verrucose-scaly like S. areolatum or S. verrucosum.

Scleroderma michiganense (Guzmán) Guzmán, Darwiniana 16: 356, 1970.

= Scleroderma hypogaeum var. michiganense Guzmán, Ciencia (Méx.) 25: 206, 1967.

Basidioma (20−) 30–40 (−60) (−80)mm diam., globose or pyriform, sessile or shortly pseudostipitate. Peridium thick, whitish to orangish-brown, verrucose-scaly with small, irregular plane or granulose scales, concolor or more brownish. Dehiscence unknown, probably by an irregular peridium cracking. Gleba white to dark brown, with thin brownish filaments. Basidiospores (13−) 15–22 (−23)μm diam., reticulated, spines and reticulum 0.8–2.5μm high. Clamp connections present.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious on soil, in Pinus forests.

Selected studied specimens. Jalisco, Nevado de Colima, alt. 3000m, breach to Canadian Foundation, Nov. 7, 1992, Ambriz s.n. (IBUG).

Remarks. Here is presented the first record of S. michiganense in Mexico, which was only known from the NE of USA (Guzmán, 1970). The verrucose to scaly peridium and the little small basidiospores, separate this species from S. hypogaeum.

Scleroderma nitidum Berk., Hooker's J. Bot. Kew Gard. Misc. 6: 173, 1854.

= Scleroderma tenerum Berk. et M.A. Curtis, in Berkeley, J. Linn. Soc., Bot. 10(46): 346, 1869.

= Veligaster nitidus (Berk.) Guzmán et Tapia, Doc. Mycol. 25(98–100): 188, 1995.

Basidiome (15−) 20–25 (−30)mm diam., globose, sessile or sharply stipitate. Peridium thin, verrucose-scaly as in S. areolatum and S. verrucosum, and with the same color, intensely rubescent, mainly in the endoperdium to vinaceous-red. Stipe 20–40 (−50)×0.5–20mm, tough, cylindric, on upper part with irregular membranaceous veil-like or granulose, hyaline to blackish patches, as those described for S. mexicana. Dehiscence like in S. areolatum and S. verrucosum. Gleba whitish to dark purpuraceous or grayish-brown, with whitish or yellowish filaments. Taste and odor intensely like rubber. Basidiospores (6−) 7–11 (−12) (−13)μm diam., echinulated, spines 0.5–2 (−2.5) μm high. Basidia 13–19 (−20)×6–10μm, pyriform, thin- or thick-walled, with 4 or 6 sterigmata. Oleiferous hyphae sometimes present in both exo- and endoperidium. Clamp connections absent.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious, caespitose or fasciculated on soil, in tropical and subtropical forests, these later with Quercus. Pantropical. See table 1 for its distribution on Mexico.

Selected studied specimens. Jalisco, Sierra de Manantlán, Puerto del Escobedo, road to Las Cabanas, Aug. 30, 1995, Sánchez-Jácome 750 (IBUG). VERACRUZ, Coatepec, near of Hacienda El Trianón, July 29, 2010, Cortés-Pérez 278 (XAL); Zoncuantla, Mpio. Coatepec, July 30, 2006, Guzmán 36516 (XAL). Yucatán, road Mérida to Telchac, 5km SW of Conkal, Aug. 5, 1983, Guzmán 23592 (XAL). Remarks. Scleroderma nitidum had been interpreted in different ways since it was described by Berkeley (1854) from Nepal. Guzmán (1967) first considered this species as an independent taxon, but Guzmán (1970) synonymized it with S. verrucosum. The pseudostipe with submembranous blackish patches described above, were the main feature to consider this fungus as Veligaster by Guzmán and Tapia (1995). The type of S. nitidum at K comprises sessile and stipitate basidiomata, withbasidiospores (8−) 9–11 (−13)μm diam., and it was collected in the eastern of Nepal, at 3000m elevation. Guzmán and Ramírez-Guillén (2010) studied a Nepal's collection, found by Guzmán in a subtropical forest with Quercus, in Dhulikhel, also in the eastern of that country, but at 1000m elevation, with basidiospores (7−) 8–11 (−12) diam. The synonymization of S. nitidum with S. tenerum, a Cuban fungus, is without discussion, as stated by Guzmán and Tapia (1995) based in the study of the type at K, which has basidiospores (7−) 9–11 (−12)μm diam.

Scleroderma polyrhizum (J.F. Gmel.) Pers., Syn. Meth. Fung. 1: 156, 1801.

= Lycoperdon polyrhizum J.F. Gmel., Syst. Nat., Edn 13, 2: 1464, 1792.

= Scleroderma geaster Fr., Syst. Mycol. 3: 46, 1829.

= Sclerangiumpolyrhizon (J.F. Gmel.) Lév., Ann. Sci. Nat., Bot., sér. 3, 9: 130, 1848.

Basidiome 60–100 diam., globose, regular or irregularly, sessile. Peridium thick, 2–10mm, smooth to rough or cracked, with cottony and fibrous mycelium and adhering soil, whitish to grayish yellow. Endoperidium whitish, probably rubescent. Dehiscence stelliform, with several recurved, thick lobes. Gleba grayish-brown to violaceous-brown, covered by a thin, cottony, white to dark brown membrane. Taste and odor probably like rubber. Basidiospores (6−) 7–11 (−12)μm diam., subreticulated, spines and reticulum 0.5–1μm high. Basidia not observed. Clamp connections present.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Solitary or gregarious on soil, mainly sandy-clay soils, hypogeous when immature to epigeous in the dehiscence. Growing in Quercus-Pinus forests, also in tropical forests. See table 1.

Selected studied specimens. Chiapas, Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Botanical Garden F. Miranda, Sept. 17, 1992, Guzmán 30516-A (XAL). Jalisco, Concepción de Buenos Aires Municipality, 1975, Puga s.n. (IBUG, XAL). Michoacán, 6km SW of Pátzcuaro, Joya de Navas, Aug. 15, 1997, Guzmán 32145-A (XAL).

Remarks. A common species in Europe, North of Africa and USA, but rare in Mexico, where it is only known from Chiapas, Jalisco (very common in this state, as reported Guzmán-Dávalos and Guzmán, 1985) and Michoacán. The records from Chiapas and Michoacán are new and it is presented the first report of this species in a tropical habitat. Some materials from Jalisco present larger basidiospores, (7−) 8–13 (−14)μm, which approach to S. floridanumGuzmán (1967, 1970), with basidiospores (9−) 10–13 (−16)μm diam. Probably S. floridanum grows in Mexico, but new studies are necessary in that species.

Scleroderma pseudostipitatum Petch, Ann. R. Bot. Gards. Peradeniya 7: 76, 1919.

= Veligaster pseudostipitatus (Petch) Guzmán et Tapia, Doc. Mycol. 25(98–100): 191, 1995.

Basidiome aprox. 30mm diam., globose but stipitate. Stipe about 45×10mm (size based only in one Mexican specimen), well formed, solid. Peridium thin, 1mm thick, rubescent, verrucose-scaly like that of Scleroderma nitidum and S. verrucosum, with submembranous, veil-like, blackish patches in the base of the globose basidiome and in the upper part of the stipe, as described in S. mexicana. Endoperidium rubescent. Gleba whitish to dark purpuraceous or grayish-brown, with whitish or yellowish filaments. Taste and odor intensely like rubber. Basidiospores (8.5−) 10–14 (−15)μm diam., echinulated, spines 1–2 (2.5)μm high. Clamp connections absent.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious on soil, in subtropical (mesophytic) forests with Quercus and Fagus. See table 1 for its Mexican distribution.

Selected studied specimens. Veracruz, Acatlán Volcano, outer slope of the volcano crater, July 13, 2005, Gándara 1345 (XAL).

Remarks. Scleroderma pseudostipitatum is very close to S. nitidum, but it separates for the bigger basidiospores. It is also related with the pseudostipitated forms of S. verrucosum, which present the same size of basidiospores, but the stipe in S. verrucosum is not well formed because it is an aggregation of mycelium in a lacunose pseudostipe. The material reported by Guzmán et al. (1997) from Zoncuantla region in Veracruz as S. pseudostipitatum for its lacunose pseudostipe, it is now considered as S. verrucosum. In this way we are reporting here, together with Cortés-Pérez (2011)S. pseudostipitatum for the first time from Mexico. It is curious that the studied material, Gándara 1345 (XAL) was found in a relict of a Fagus grandifolia var. mexicana (Martínez) Little. Scleroderma pseudostipitatum was only known from the type locality on Sri Lanka (Ceylon) by Petch (type at BPI and K studied by Guzmán, 1970).

Scleroderma texense Berk., London J. Bot. 4: 308, 1845.

= Scleroderma patens Lloyd, Mycol. Writ. 2, Letter 22: 275, 1906.

= Scleroderma australe var. imbricatum G. Cunn., Proc. R. Soc. N.S.W. 56: 282, 1931.

= Scleroderma furfurellum Zeller, Mycologia 39: 296, 1947.

Basidiome very similar to Scleroderma polyrhizum, except that the exoperidium is more yellowish or some orangish, strongly scaly in the adult stages, with large folded thick scales. Endoperidium rubescent. Gleba surrounded by a thin cottony and white layer. Taste and odor intensely like rubber. Basidiospores (6−) 7–11 (−12)μm, subreticulated, spines and reticulum up to 0.8μm high. Exoperidium with thick-walled or solid hyphae. Endoperidium with thin-walled hypae. Basidia (36−) 40–55 (−60) (−75)×(12−) 13–17μm, 4− to 6− sterigmata, hyaline, claviform or subglobose, thick-walled, with a long narrow base. Clamp connections present.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Hypogeous to epigeous in soil, mainly orangish-red clay soils, in Pinus-Quercus forests in transition with tropical vegetation. Known from the SE of USA to Mexico and Guatemala, also in the Caribbean region, Africa, Southern Asia and Australia (Guzmán, 1970). Calonge (1982) reported this species from Spain as a rare fungus. We are recording S. texense for the first time from Veracruz, together with Cortés-Pérez (2011). See Mexican distribution in table 1.

Selected studied specimens. Jalisco, near of San Sebastián del Oeste, Sept. 12, 1987, Guzmán-Dávalos 4018 (IBUG). State of Mexico, Valle de Bravo, Oct. 7, 2000, Guzmán 34363 (XAL). Veracruz, region of Teocelo, Oct. 15, 2011, Cortés-Pérez 757 (XAL).

Remarks. This is one of the most common species in Mexico in the subtropical regions with Pinus and Quercus. Several authors (e.g. Lloyd, 1905, in Lloyd 1898–1926) considered S. texense as a synonym of S. polyrhizum, others as Coker and Couch (1928), regarded S. texense as a synonym of S. bovista, without any argument. šebek (1953) synonymized S. texense with S. verrucosum, together with S. columnare. The study of the type of S. texense at K (Guzmán, 1970), corroborated that it is a well-defined independent species.

Scleroderma verrucosum (Bull.) Pers., Syn. Meth. Fung. 1: 154, 1801.

= Lycoperdon verrucosum Bull., Hist. Champ. France (Paris) 1: 24, 1791.

= S. verrucosum s. Guzmán, Darwiniana 16: 276, 1970 p.p., non S. verrucosum s. Guzmán, Ciencia (Méx.) 25: 199, 1967.

Basidiome (20−) 25–30 (−45)mm diam., globose, shortly pseudostipitate. Peridium thin, membranaceous when mature, yellowish-brown, covered with small dark brown or blackish scales. Pseudostipe short, up to 15mm long, solid, pale brownish, frequently lacunose, up 30mm long, whitish to pale brownish. Basidiospores (8−) 9–12 (−14)μm, echinulate, with spines 0.5–2μm high. Clamp connections absent. Other features as those in S. nitidum and S. areolatum.

Taxonomic summaryHabitat and distribution. Gregarious, sometimes fasciculated, epigeous on soil, in Pinus-Quercus or cloudy forests. Common in Europa and North America. See table 1 for the Mexican distribution.

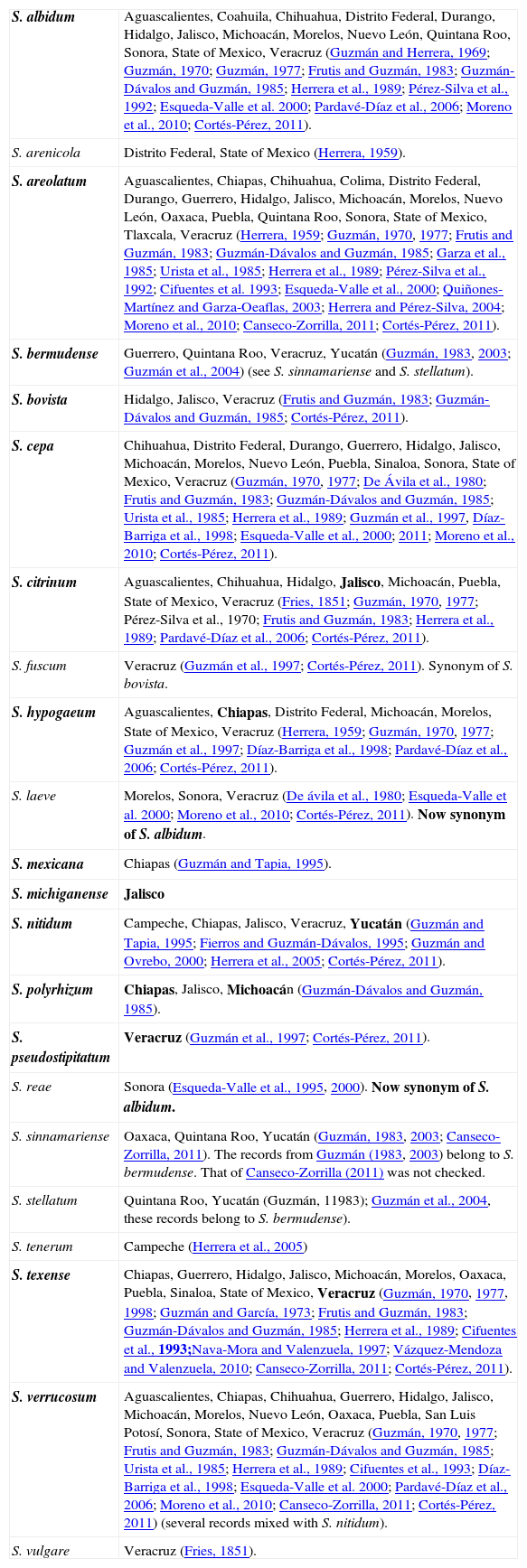

Species of Scleroderma from Mexico (in boldface valid species and new records).

Selected studied specimens. Jalisco, Zapopan Municipality, Santa Lucía road to El Guaje, Sept. 8, 2004, Sánchez-Jácome 1078 (IBUG). PUEBLA, Techacapán Hill, Sept. 24, 1989, Bandala 1794 (XAL). Veracruz, old road Xalapa to Coatepec, region of Zoncuantla, Oct. 1, 2008, Guzmán 38095; Jun. 21, 2009, Guzmán 38132 (XAL).

Remarks. Scleroderma verrucosum is one of the most reported species in the genus, in part for its abundance, but also because several times specimens of S. areolatum and S. nitidum are erroneously determined. Smith (1951) mixed S. verrucosum with S. lycoperdoides, which is a synonym of S. areolatum. He described basidiospores (8−) 10–15 (−18)μm diam.

DiscussionEcological observations and distribution. All species of Scleroderma have gregarious basidiomata, although sometimes they are caespitose or fasciculose. They are hypogeous or subhypogeous in immature stages to epigeous in the maturity where the basidiospores are expelled. However, some species, as S. areolatum, S. cepa, S. citrinum and S. bovista are epigeous even in the immature states. They grow on soil or sand, in this latter case in S. bermudense and S. polyrhizum, also in S. hypogaeum which is common in forests soils. Scleroderma is typical ectomycorrhizic with several trees or shrubs as Abies, Betula, Coccoloba, Eucalyptus, Nothofagus, Pinus, Populus, and Quercus. The tropical and subtropical species of Scleroderma as S. columnare, S. hypogaeum, S. mexicana, and S. sinnamariense are associated with Caesalpinaceae, Dipterocarpaceae, or Phyllanthaceae trees, among others. Some species as S. citrinum are apparently saprobes until they are able to find a suitable host (Sims et al., 1997; Giachini et al., 2000; Gurgel et al., 2008; Sanon et al., 2009). It is interesting to observe that one collection of S. hypogaeum was found in Veracruz (Zoncuantla) growing on the stipe of a tree fern [Cyathea arborea (L.) Sm.], at more than 1m up the soil level, and S. nitidum several times inside of old flower clay vases in a garden forest with Quercus, which show the large extension of the mycelium. Xerocomus parasiticus (Bull.) Quél. is frequently reported in Europe as a parasitic fungus on Scleroderma citrinum; however, this case is unknown in Mexico. Guzmán (1970) reported a specimen of S. floridanum parasited with Hypomyces chrysospermus Tul. et C. Tul. We are recording now a S. verrucosum specimen (Guzmán 38095) parasited by an immature asexual state of Hypomyces.

Phylogenetic analyses in Scleroderma. One of the earlier works on the phylogenetic analyses on Scleroderma is that by Hibbett et al. (1997), followed by Hibbett and Binder (2002), Binder and Hibbett (2006), and Louzan et al. (2007), which considered Scleroderma belong to Boletales together with other sclerodermataceous fungi, based mainly in ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequences or in sequences of the mitochondrial protein genes (Kretzer and Bruns, 1999). Sims et al. (1999) studied the culture features (morphology and growth rate), isozyme variation, and rDNA restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLPs) in S. citrinum, S. columnare, S. sinnamariense, and S. verrucosum from Malaysia, Philippines, and Indonesia. Sanon et al. (2009) analyzes molecularly tropical sclerodermas. Phosri et al. (2009) made a phylogenetic study using the rDNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) with S. areolatum, S. bovista, S. cepa, S. citrinum, S. michiganense, S. polyrhizum, S. septentrionale, S. sinnamariense, and S. verrucosum from the USA, Europe and Thailand, where they found that Guzmán's (1967, 1970) classification on 3 sections on the genus is natural.

Some ethnomycological observations. It seems that Scleroderma has not ethnomycological importance in Mexico, although sometimes basidiomata with dusty gleba, as S. areolatum, S, nitidum, and S. verrucosum, which people mixed with Lycoperdon spp., Bovista spp. and Calvatia spp. are used to stop the bleed from wounds. Guzmán (1997) reported the common names “zitlananácatl malo” and “jicamo real de venado” for S. texense and S. verrucosum, respectively, both as poisonous. Also he considered the name “papas de la tierra” for all the species. People in general considered all the species of Scleroderma as poisonous. However, De Ávila et al. (1980) reported S. laeve as edible in Morelos, but Cifuentes et al. (1993) stated that all species in Guerrero are toxic. Christensen et al. (2008) in a confused report, considered S. sinnamariense, S. polyrhizum, and S. verrucosum as edible in Nepal. Šebek (1953) reported young stages of Scleroderma used to adulterated truffles. Mcllvaine and Murrill (cited by Stevenson and Benjamin, 1961) stated that the species of Scleroderma, specifically S. aurantium, are edible. There is the curious use of Scleroderma sp. (probably S. cepa, see discussion in that), in Tanzania, according to Härkönen et al. (2003), to avoid bees' stings, when collecting honey from honeycombs. The fungus is attached to a stick, set on fire and then pushed into a honeycomb. The smoke sedates the bees, so that honeycomb can be removed. Stevenson and Benjamin (1961) described a case of poisoning in the USA, where after eating S. cepa, stomach pains, nauseas, and muscular paralysis were presented, but after the person vomited he felt well. Also Guzmán through A.H. Smith got a communication of a poisoning event by Scleroderma in Canada observed by R.F. Cain. The Canadian specimen was determined by Guzmán as S. cepa. Coccia et al. (1990) considered that S. citrinum is poisonous. The only poisoning case by Scleroderma known in Mexico is by Ott et al. (1975) in San Miguel del Progreso, Oax., when they were experimenting on some narcotic lycoperdaceous fungi, and a person of the team ate S. verrucosum, who produced a poisoning with stomach pain and vomit.

The authors express their thanks to the authorities of their institutions, for the support on their researches. Also to the curators of the herbaria BPI, FH, K, MICH, NY, OSC, and PC, who loaned to Guzmán in the past important collections and types. The following colleagues, students and assistants are thanked for their help in several duties, as bibliographic sources, specimens' supplies, field work, microscopic observations, and herbarium and computer shores: T. J. Baroni, F. D Calonge, J. Cifuentes, V. G. Cortez, E. Gándara, R. Gazis, M. Härkönen, M. Hernández, T. Herrera, E. Horak, J. Lara-Carmona, D.J. Lodge, G. Mata, C. L. Ovrebo, M. Piepenbring, V. Ramírez-Cruz, F. Tapia, J. Trappe, R. Valenzuela, and R. Watling. Also Brian Akers, who kindly reviewed this paper.