The organization and methodology of providing services to athletes through Olympic high performance centers varies among the National Olympic Committees (NOC). Between NOCs, provider composition and methodology for the delivery of services differs. Services provided typically include sports medicine and sports performance. NOCs may provide service through a university-based system or high performance centers. The United States Olympic Committee (USOC) provides services using multiple approaches through a hybrid model that includes three Olympic Training Centers, National Governing Bodies (NGB) high performance centers and independent specialty care centers. Some highly developed National Governing Bodies have dedicated high performance training centers that serve only their sport. The model of sports medicine and sports performance programming utilized by the USOC Olympic Training Centers is described in this manuscript.

United States athletes who train with the intent of performing at Olympic Games are distributed throughout the country. The U.S. is a geographically large country (9,826,675 square kilometers), it is similar in size to Brazil (8,514,877 square kilometers). In the U.S., Olympic caliber athletes are broadly distributed throughout the U.S. In order to help meet high performance needs the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) is required to implement multiple strategies to provide care and support U.S. Olympic and Paralympic athletes. The USOC’s high performance goal is to provide stable and successful high performance services in support of U.S. Olympic and Paralympic athletes. In order to achieve this goal, the USOC has created a hybrid approach to provide efficient and effective sport performance services.

The hybrid approach includes three principle vectors of performance-related support for the athletes. These three approaches are provided through Olympic Training Centers (OTC), NGB-driven high performance centers and USOC affiliated medical centers.This plan allows for a broad based plan of care for the athletes to meet their geographic and service-level needs.

The (USOC): has three Olympic Training Centers (OTC) strategically dispersed across the country to provide sports performance services nationwide. These OTCs are located diagonally across the U.S., running from the northeast to the southwest. The OTCs are located in Lake Placid, New York; Colorado Springs, Colorado; and Chula Vista, California. Each center is designed to offer a broad spectrum of high performance services with a regional focus. Athletes are chosen to train at an OTC by their respective sport Federation or NGB. The OTCs offer athletes support housing, dining, training facilities, local transportation, recreational facilities, athlete services, and professional development programs. Typical sports performance services providedat the OTC’s also include sports medicine, exercise physiology, strength and conditioning, sports nutrition, sports psychology, and biomechanical analytics.

In addition to USOC’s OTCs, several high level National Governing Bodieshave developed their own high performance training centers. For example, the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association’s (USSA) Center of Excellence in Park City, Utah, is a national training and education center that grants training facilities and serves as an educational resource for the USSA’s athletes, coaches, officials, clubs, parents, volunteers, and other stakeholders nationwide. The types and levels of services provided at NGB high performance training centers varies depending on individual sport needs and NGB funding.

Sopport provided by the USOC’s sports performance division includes USOC-affiliated independent medical specialty centers of care that provide services to the NGBs elite athlete population. For example, minimally invasive spinal surgery is provided at the D.I.S.C. Sports and Spine Center in the Los Angeles area. The interdisciplinary clinicians at D.I.S.C use an integrated approach to clinical care. Relationships with specialty care centers of this caliber help USOC Sports Medicine Doctors provide high level service across the United States in regions without USOC clinics.

Usoc sports medicine and sports performance organizational structureThis article will focuses on the model of sports medicine care and sports performance support provided at the USOC OTCs. The resident Athletes are in the top 10-15% of their sport(s) in the U.S. Each athlete’s respective NGB identify these athletes to be selected them to live and train at an OTC. There is designated a number of resident beds allocated each year for resident athletes.

The demographics of the athletes is defined in part by the facilities associated with the OTC. As expected, the Lake Placid OTC is home to many winter athletes, especially the sliding disciplines of bobsled, luge a skeleton and biathlon. Frequent visits from figure skating, ice hockey, skiing, ski jumping and speed skating athletes occur on a yearly basis. The Chula Vista, California OTC is just south of San Diego and serves as home to the Olympic sports of archery, BMX, canoe/kayak, field hockey, rowing, soccer, as well as rugby and some cycling, beach volleyball, track & field and triathlon athletes. In Colorado Springs, USA Swimming and USA Shooting have their national headquarters on the complex to additionally the city is home to more than 15 other member organizations, as well as two international sports federations. The Colorado Springs OTC is home to several NGBs including triathlon, fencing, men’s gymnastics, pentathlon, three disciplines of wrestling, shooting, track & field weightlifting. Paralympic sports complex include shooting, swimming, cycling, and judo.

The USOC Sports Performance and sports medicine divisions provides structures for two separate but intertwined divisions. USOC Sports Performance and sports medicine functionality requires effective communication and interdivisional planning for the athlete and NGB’s sport performance and sport medicine needs. These two Divisions are in close proximity to each other in regards to physical location as well as interdepartmental communications. Successful collaboration requires an environment of shared respect and trust, as well as education on both sides, along with established and strong.

Visible involvement of the chief executive and senior management also is essential. Senior management sets the standards for service delivery and drives the change process. The USOC sport performance division is led by the chief of sports performance who reports to the chief executive officer of the USOC. The chief of sports performance employs Team Leaders whom oversee the services provided by the USOC to NGBs. The USOC loosely categorizes NGBs by type of sport into “sportfolios” such as combat sports, team sports, etc. In turn, each team leader in has at least one high performance director who manages the USOC allocations and high performance plans of the individual NGBs as they relate to the USOC’s support of the NGB’s athletes. The sportfolios contain sports performance specialists in the discipline of the specific sportfolio. Each sportfolio includes exercise physiology strength and conditioning, sports nutrition, sports psychology, and biomechanical analytics.

The USOC sports medicine division is led by the managing director of sports medicine who reports to the executive administrative officer. This division of the USOC is responsible for clinical services at the OTCs, Games medical services and the development and maintenance of a nationwide network of medical providers who provide services in support of the athletes. Each of the three OTC sports medicine clinics also has a manager in place as well as multiple clinicians from varied backgrounds. The manager oversees the local implementation of the overall sports medicine directives of the sports medicine and sports performance divisions. (Figure 1)

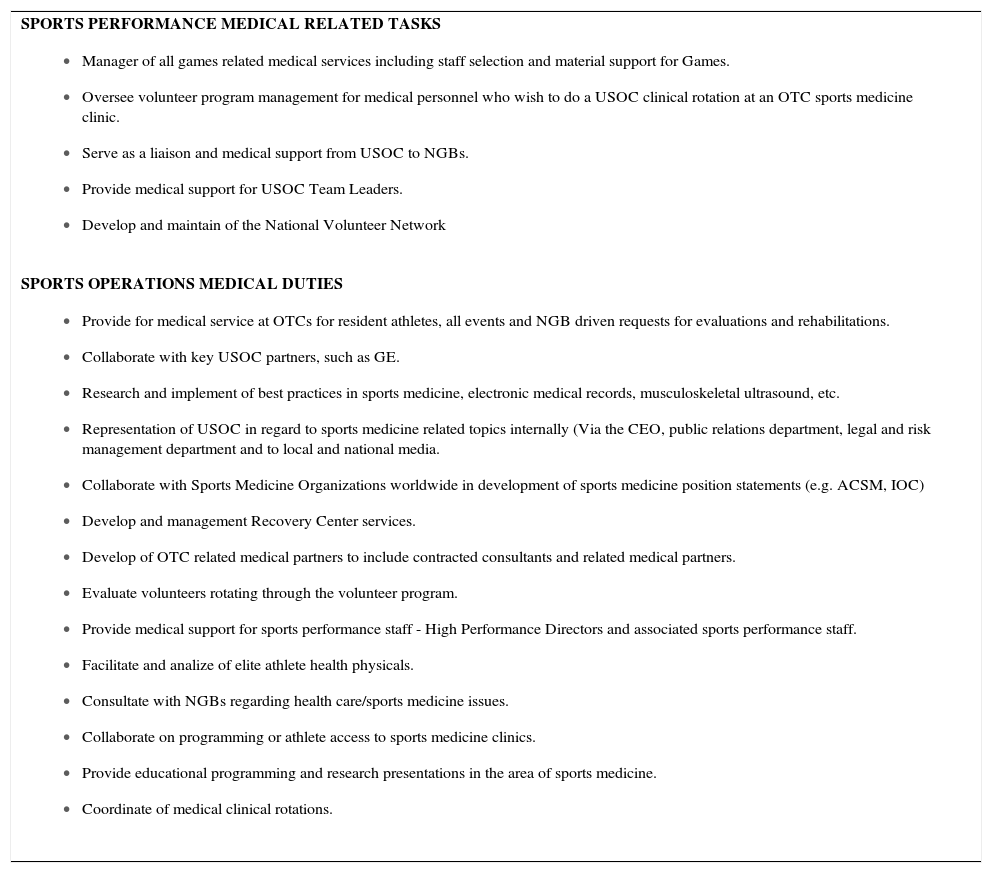

In addition to acumen in the realm of sports medicine, the importance of the sports medicine director having the excellent communication skills as well as superior leadership abilities should not be underestimated. (9) Studies of intercollegiate team physicians in the U.S demonstrate approximately one quarter of musculoskeletal injuries required a radiograph, and approximately 1 in 11 injuries required an MRI. Fortunately, only 4% of musculoskeletal injuries required surgery. (10) The sports medicine director must have the licensure to diagnosis, order and interpret the appropriate imaging, laboratory and special studies. The appropriate communication of clinical and significant findings to the sports medicine consultants is a key to the success of the program. This conclusion also leads to the reasoning that it is critical that the medical director of the sports medicine team be trained in musculoskeletal medicine. There are several components to the medical director’s duties (see Table 1).

Current roles and responsibilities for usoc medical director

SPORTS PERFORMANCE MEDICAL RELATED TASKS

|

SPORTS OPERATIONS MEDICAL DUTIES

|

The USOC medical director should exhibit the following three core functions:

- 1)

Understanding the position as one of a network of professional colleagues.

- 2)

The obligation to be clinically competent and constantly striving to maintain current sports medicine knowledge.

- 3)

Embracing the commitment to patient center care and a collaborative approach to practice.

According to the International Olympic Committee, it is the responsibility of the sports medicine profession to care for the health and welfare of Olympic athletes, treat and prevent injuries, conduct medical examinations, evaluate performance capacity, provide nutritional advice, prescribe and supervise training programs and monitor substance use. The USOC clinical sports medicine division follows this pathway by recognizing that sports medicine is a interdisciplinary field concerned with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of injuries and illnesses associated with participation in sport, exercise, and other forms of physical activity.

The patient population seen in OTC clinics is completely comprised of elite athletes thus sport-specific healthcare professions have emerged to meet the health care demands of elite athlete. Traditionally, in the U.S. frontline providers of the sports medicine team are certified athletic trainers. These skilled individuals provide the vanguard medical services at practices and events. Recognition that certified athletic trainers are an important and essential part of the team is a essential.

The USOC sports medicine department has moved away from traditional athletic training rooms to a new model of sports medicine care that incorporates doctors of chiropractic with specialty education in the field of sports medicine, sports physical therapists and athletic trainers as the core clinical staff. This model is not that different than other National Organization Committees. In addition to the afore mentioned clinicians, MD and DO physicians from across the U.S. also serve to provide athletic care, including medical consultants that serve in support of each OTC sports medicine clinic.

The demographics of USOC OTC sports medicine clinic office visits are similar to FIFA World Cup because the vast majority largely comprised of nonsurgical musculoskeletal complaints that lead to limited time loss from practice or competition.(11) These type of injuries are aptly cared for using an integrated interdisciplinary approach. An interdisciplinary sports medicine approach may be defined as the process of evaluation and management whereby health professionals share their knowledge, attitudes and skills as needed for the interdisciplinary application or practice of health care from at least two distinct health professions. The USOC sports medicine conservative clinicians are thoroughly trained to recognize the limits of conservative management and they recognize the criticality of having MD/DO physicians intimately involved in the assessment and management of patients with substantial illness or musculoskeletal injuries that are not amendable to conservative approaches.

Approximately 25,000 patient visits occur annually across the three USOC sports medicine clinics. Each OTC’s sports medicine clinic is staffed with a combination of athletic trainers, physical therapists, and doctors of chiropractic with specialty training in sports medicine. In addition to full-time clinic staff, local physicians of multiple specialties are utilized on a consulting physician basis for co-management of select conditions. These include weekly rotations by family practice physicians and orthopedic surgeons affiliated with each clinic. Other specialties are called upon on an as needed basis, including orthopedic surgeons specializing in the spine, hand, foot and ankle, neurosurgeons, internal medicine specialists, endocrinologists, podiatrists, radiologists, gynecologists, pain management physicians, neuropsychologists, optometrists, dentists and sport dieticians.

Clinic staffing is further supported by a national network of volunteer sports medicine clinicians on an as-needed basis. The national volunteer program hosts athletic trainers, physical therapists, doctors of chiropractic with specialty training in sports medicine, medical doctors and doctors of osteopathy from multiple specialties. Clinicians accepted to participate in the program attend a two-week clinical rotation where they work as part of the OTC clinic staff. Upon completion of the rotation the clinicians are evaluated based on performance and ability to work in an interdisciplinary setting. Top candidates are invited back to work as volunteer staff at USOC and NGB events, including Pan-American and Olympic Games.

Diagnostic services available differ by clinic depending on clinic volume and staff training. Laboratory services are available at all clinics. Hematology and urinalysis are the most commonly ordered studies, with some clinics ordering more than 500 individual studies per year. Individual studies may be ordered in routine screening physicals for periodic physiologic evaluation for sports science purposes, annual preparticipation examinations and as a tool for diagnosing of pathological conditions.

The diagnostic imaging services available vary depending on clinic need. The Colorado Springs OTC is equipped with digital radiography and musculoskeletal ultrasound, while the Lake Placid and Chula Vista OTC’s have musculoskeletal ultrasonography available on site. The need for special imaging at OTC clinics is relatively low, as ultrasonography and radiography have proven to be an effective first line imaging study for musculoskeletal pathology. For example, in 2011 at the Colorado Springs OTC, 347 musculoskeletal ultrasounds were ordered, compared with only 82 MRI’s. Musculoskeletal ultrasound has gained popularity in sports medicine due to its portability, cost effectiveness and diagnostic utility. Special studies such as MRI, bone densitometry, and CT scans are performed at outside imaging facilities.

Although the types of treatment rendered differs for each clinic depending on athlete needs and clinician preference, several trends regarding the most commonly performed therapies have been identified. Regardless of terminal degree, manual therapies are the most commonly utilized type of therapy. This includes soft tissue mobilization, stretching, joint mobilization and joint manipulation. The second most common type of treatment performed is rehabilitative exercise. We believe these forms of conservative treatment have emerged as first line treatments in the sports medicine setting due to their effectiveness and low relative risk of negative outcomes. The third most utilized treatment across OTC’s is categorized as passive modalities, such as ice, ultrasound, vibration, heat, light and compression treatments. These techniques represent a very low percentage of services performed (less than 5%), and have relatively lower evidence for effectiveness.

Communication in the interdisciplinary settingMaintaining open paths of communication between all members of the sports medicine team is the biggest key to success to avoid confusion and pitfalls. The utilization of multiple centers for the care of the athlete requires advance planning in regards to continuity of care and communication pathways. Depending on their training cycle, individual athletes may present at all three OTCs in any given year. Developing a sports medicine communication strategy involves several important considerations that should be addressed in advance of the need for implementation of that strategy (1).

Electronic medical records (EMR) has allowed clinicians to collaborate across the U.S. to the benefit of the athlete. EMR also allows the athlete to access their own medical records from anywhere in the world with internet access. In addition to broad based access the EMR features analytics to allow the USOC sports performance teams to perform better analysis regarding injury and illness in the athletic population.

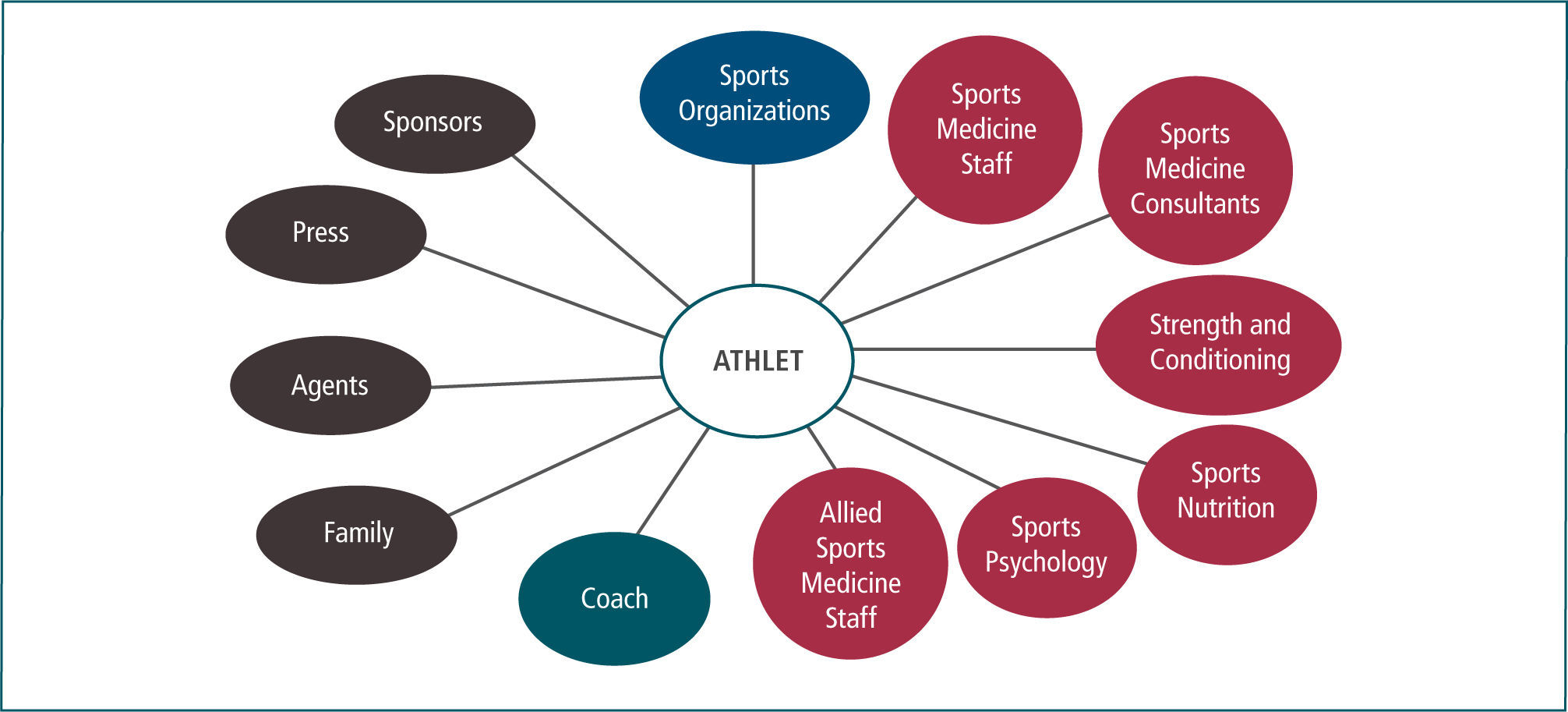

Sports medicine communication involves not only technology, but also internal and external partners. Internal partners include health care providers who are directly caring or providing consultations for the athlete. These may include the athlete’s primary care physician, orthopedic surgeon, physiotherapist, chiropractor or sport’s psychologist.

The internal partners should share information in order to develop a team approach to the athlete’s care. An exception is when the athlete specifically identifies confidential information which he or she does not want to communicate to others.

External partners are comprised of those groups of individuals who have a vested interest in the athlete’s health status, but are not directly involved in the delivery of health care services. These groups of people or organizations will present different levels of complexity in regards to communication of the athlete’s health status. More often than not, in the U.S. the health care team will be required to obtain the athlete’s permission before disclosing health information to external partners.

Some groups of individuals can be considered both internal and external partners, for example the athlete’s coach and/or (NGB). As individuals they may not have direct access to the athlete’s health care status, but most likely these two groups will be involved in internal sporting decisions regarding team selection and the strategy around an athlete’s availability for competitions.

The diagram below depicts the internal and external partners involved in athlete communication issues. The athlete is the center of the hub of communication in regard to clinical care. Internal communications are defined as those communications that occur within the “protected confines of the sports medicine organizational structure.” The athlete’s family, coaches and “sports organizations” may or may not be included in protected communications. Examples of rules in sports include sports organization communications such as boxing commissions, NGBs and athletic associations that have recognized doctrine in place for the athlete regarding the communication of sports medicine related issues.

The United States Olympic Committee’s sports medicine and high performance support for U.S. National Governing Bodies and their athletes involves multiple pathways of support including sports medicine clinics located at three Olympic Training Centers, National Governing Bodies’ independently operated high performance centers, and a national network of sports medicine and sports performance clinicians. USOC clinical sports medicine is delivered using an established interdisciplinary team of medical providers that implement an integrated, patient centered approach to care. Open communication and teamwork amongst care providers are important cornerstone to successful outcomes. The utilization of conservative physical medicine providers coupled with traditional medical physicians who serve in close consultation has proven an effective method of delivering high performance care to the athlete (Figure 1).

The author has no conflicts of interests with this article.