To examine the association between lifestyle factors (body mass index, smoking, alcohol consumption, coffee intake, physical activity, sauna and cell phone usage, wearing tight-fitting underwear), and conventional semen parameters.

Materials and methods1311 participants who attended the Andrology Clinic were included in the study. All participants were separated into two groups as men with normozoospermia and dysspermia. All participants answered a questionnaire which contains questions about the modifiable lifestyle factors. The total risk scores were calculated after all the positive lifestyle factors had been counted.

ResultsMen with normozoospermia and dysspermia consisted of 852 (65.0%) and 459 (35.0%) participants respectively. A negative relationship between the wearing of tight underwear and having normal semen parameters was detected between the two groups (p=0.004). While going to a sauna regularly was negatively related to semen concentration, wearing tight underwear was also related to both lower motility, normal morphology as well as semen concentration (p<0.05). While the total score of all participants was 5.22±1.34 point, there were no statistical differences between the two groups (p=0.332). It was found that having 3 more or fewer points was not related to any type of semen parameters and results of a spermiogram.

ConclusionThe clinicians should give advice to infertile male patients about changing their risky lifestyle, for infertility, to a healthy lifestyle for fertility. Better designed studies, with larger sample sizes using conventional semen analysis with sperm DNA analysis methods, should be planned to identify the possible effects of lifestyle factors on semen quality.

Examinar la asociación entre los factores asociados al estilo de vida (índice de masa corporal, tabaquismo, consumo de alcohol, ingesta de café, actividad física, sauna, uso del teléfono móvil y llevar ropa interior ajustada), y los parámetros seminales convencionales.

Materiales y métodosSe incluyó en el estudio a 1.311 participantes que acudieron a la Clínica de Andrología. Se separó a los participantes en 2 grupos: varones con normozoospermia o dispermia. Todos los participantes respondieron a un cuestionario que contenía preguntas relativas a los factores modificables asociados al estilo de vida. Se calcularon las puntuaciones de riesgo total tras el recuento de todos los factores positivos del estilo de vida.

ResultadosDe entre los participantes, el número de varones con normozoospermia ascendió a 852 (65%) y a 459 (35%) los varones con dispermia. Se detectó una relación negativa entre llevar ropa interior ajustada y tener parámetros normales de semen entre los 2 grupos (p=0,004). Mientras el acudir regularmente a una sauna guardó una relación negativa con la concentración de semen, el llevar ropa interior ajustada se relacionó también con menor movilidad, morfología normal y concentración del semen (p<0,05). A pesar de que la puntuación total de todos los participantes fue de 5,22±1,34 puntos, no se encontraron diferencias estadísticas entre los 2 grupos (p=0,332). También se encontró que tener 3 puntos menos, o más, no guardaba relación con ningún tipo de parámetro seminal y los resultados del espermiograma.

ConclusiónLos clínicos deberían asesorar a los varones infértiles acerca de modificar su estilo de vida de riesgo de infertilidad, llevando una vida sana de cara a la fertilidad. Deberán planificarse y diseñarse estudios con mayores tamaños de muestra, utilizando análisis convencionales de semen con métodos analíticos de ADN espermático, para identificar los posibles efectos en la calidad del semen de los factores asociados al estilo de vida en DNA.

Infertility, a global health problem, is defined as a failure to conceive after 12 months of regular, unprotected sexual intercourse. It is estimated that one-in-six couples experience some form of infertility during their reproductive lifetime and the male factor infertility represents 30% of the diagnosis in infertile couples.1 Worldwide, sperm counts are estimated to have dropped by 50% since the 1930s2 and a study has shown that only one in four men had optimal sperm concentration and morphology.3 While much less is known about male infertility than about female infertility by both qualified medical professionals and the public, the cause of rising male infertility is not clearly known. The cause of rising male infertility is not clearly known, however it is believed that it is affected by several factors. Modifiable risk factors such as smoking, alcohol, a sedentary lifestyle, tight underwear, using a sauna, and cell phone usage may have an impact on male infertility as with female infertility. Although the strength of evidence is relatively weak,4 it was suggested that clinicians give advice about not smoking, not consuming alcohol, not wearing tight underwear, and having a body mass index (BMI) of ≤29 to infertile male patients.5

Due to the uncertainty on the effect of lifestyle factors on male reproducibility, we wanted to examine the association between lifestyle factors, (body mass index, smoking, alcohol consumption, coffee intake, physical activity, using a sauna, cell phone usage, and wearing tight-fitting underwear), and semen parameters in this study.

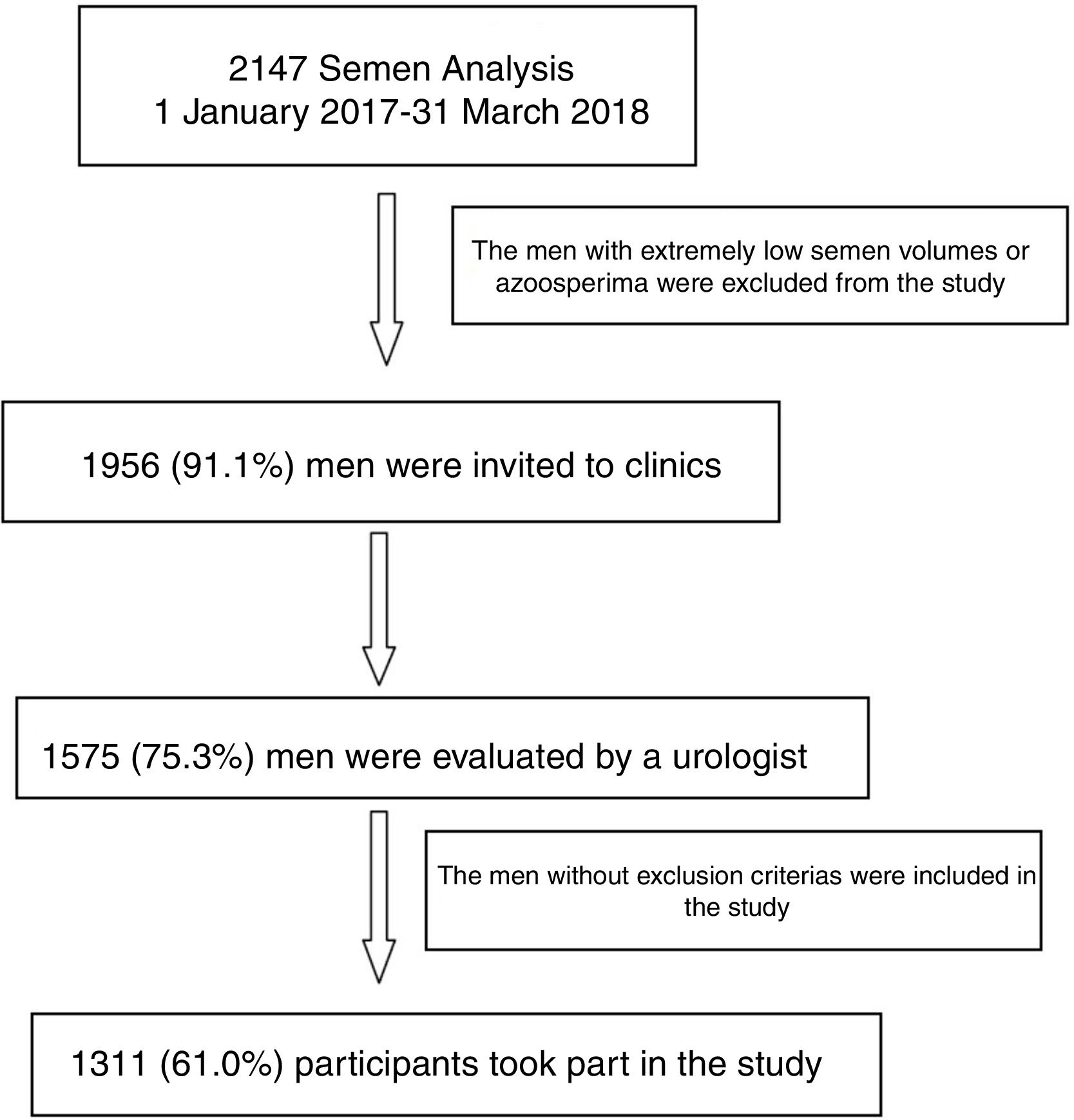

Materials and methodsStudy setting and designAfter taking the local ethical approval, 2147 semen analysis results, which were performed at the Eskisehir State Hospital Andrology Laboratory, between 1 January 2017 and 31 March 2018, were evaluated retrospectively (Fig. 1). Firstly, the men with extremely low semen volumes or azoosperima were excluded. The remaining 1956 men were invited to the Eskisehir State Hospital Urology Department to participate in the study. 1575 (73.3%) men agreed and were evaluated by an urologist. The men with pathological conditions likely to affect sperm quality, such as having history of prolonged medication, intake of indigenous medications/herbal preparations/tonics, occupational exposure to chemicals or excessive heat; history of injury to testes, varicocele, hydrocele, undescended testis or its corrective surgery, vasectomy-reversal surgery, history of any chronic illness like tuberculosis, mumps were excluded. To ensure strict selection; ex-alcoholics and ex-smokers, passive smokers, and those who only participate in the other lifestyle factors irregularly were also excluded. After these exclusion criteria, the written informed consent was obtained from 1311 participants (61.0%) of this study. All participants were separated into the two groups. Men with normozoosperima and men with dysspermia, (semen results as asthenozoospermia and/or teratozoospermia and/or oligozoospermia or oligoteratoasthenozoospermia) were identified respectively.

All participants answered a questionnaire which contains questions about demographic characteristics and about smoking, alcohol consumption, coffee intake, physical activity, sauna usage, cell phone usage, and the wearing of tight-fitting underwear. The data of the weight and height of the participants were collected from the application data when the semen was collected. BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by squared height in meters. The lifestyle factors were coded positively if the Body Mass Index was ≥25; he smoked every day; drank any amount of alcohol; drank more than 3 cups of coffee a day; did not do any type of exercise regularly; regularly wore tight underwear; went to a sauna regularly, or used a cell phone≥10 years, during the 3-month window before semen collection. The total risk scores were calculated after the all positive codes were totalled.

Semen analysisMasturbation was the main method used for semen production after a period of sexual abstinence of a mean 3–6 days. All semen samples were received in the laboratory within 30min of production. After liquefaction for 30min, or a maximum of 60min, semen samples were evaluated for sperm count, motility, and morphology. The volume of the ejaculate was determined by aspirating the liquefied sample into a graduated disposable pipette. Sperm counting and motility assessments were performed following the instructions of the counting chamber manufacturer (Makler Counting Chamber, Sefi Medical Instruments, Haifa, Israel). A volume of 3–5μL of each semen sample was transferred to the center of the chamber. The sperm count was performed in 10 squares of the chamber. The total sperm count is the end concentration expressed as 106 spermatozoa/ml. Sperm motility was assessed in 100 random spermatozoa by characterizing them as (i) rapidly forward, fast progressive motility, (ii) moderately forward, slow progressive motility, (iii) jerky non-progressive motility, and (iv) immotile/no movement, and the motility was expressed as a percentage. Reference values used were based on the 95% lower reference ranges established by the World Health Organization guidelines criteria6. Sperm morphology was quantified using strict Kruger criteria.7 These parameters, when taken together, indicated the presence or absence of the four main semen variables: normozoospermia, asthenozoospermia, teratozoospermia, oligozoospermia.

Statistical analysisThe continuous data was given as Mean±Standard Deviation while the categorical data was given as a percentage (%). The Shapiro Wilk test was used to analyze whether the data was compatible with normal distribution. In case there were groups not compatible with the normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test was used for the cases with two groups and the Kruskal–Wallis H test was used for the cases with three or more groups. The Pearson Chi-Square was used in order to carry out a crosstab analysis. For multifactorial lifestyle influence patients were evaluated with a point-based system with a cut-off value>2 for ‘risky lifestyle for infertility’ by using ROC (Receiver-Operating Characteristics) analysis. All the data was analyzed by IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2012. IBM Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) and MecCalc 6. The statistical significance threshold was accepted as p<0.05.

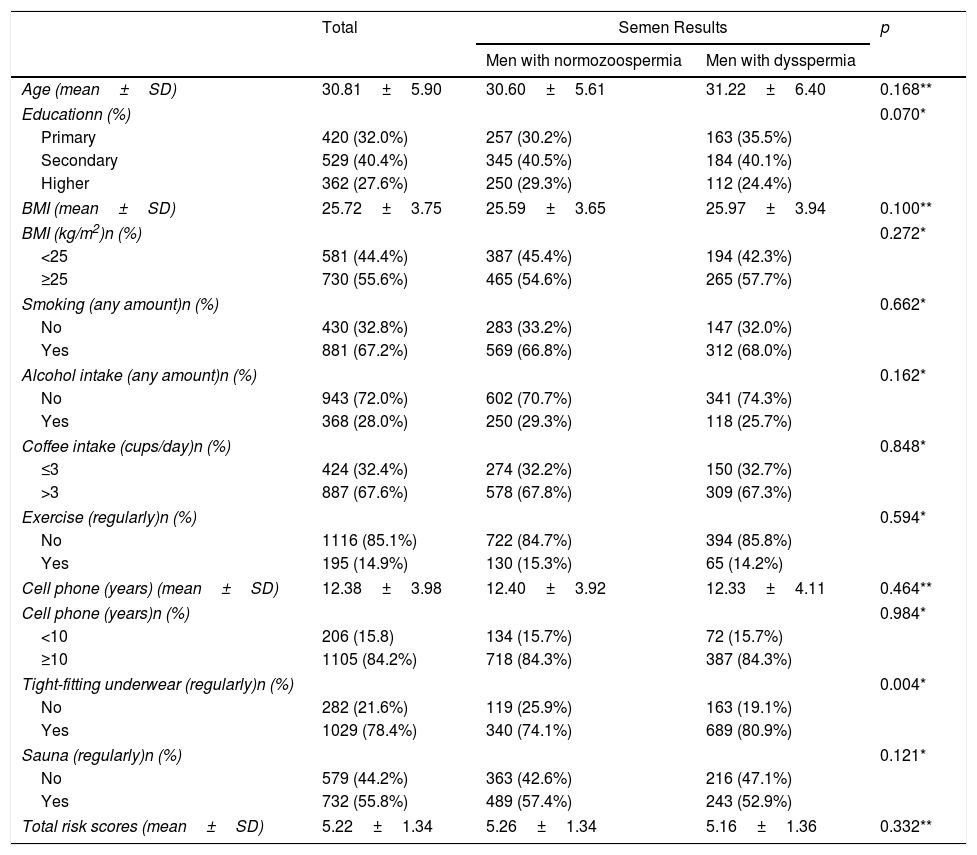

ResultsThe study population consisted of 1311 participants who attended an andrology laboratory and were available for the study. The mean age of the men participating in this study was 30.81±5.90. Most of them had a secondary education (40.3%) and were overweight or obese (BMI≥25kg/m2) (55.6%); smoked regularly(67.2%); did not drink any amount of alcohol (72.0%); drank more than 3 cups of coffee a day (67.6%); did not do any type of exercise regularly (85.1%); used cell phone≥10 years (84.2%); regularly wore tight underwear (78.4%); went to a sauna regularly (55.8%). All participants were separated into two groups by their sperm results. Group 1 (men with normozoospemia) and Group 2 (men with dysspermia) consisted of 852 (65.0%) and 459 (35.0%) participants respectively. It was detected that there was no statistical difference at the education level, age and lifestyle factors except wearing tight underwear between two groups (Table 1). Only a negative relationship between the wearing of tight underwear and having normal semen parameters was detected (p=0.004). All participants were scored according to their lifestyle factors. While the all participants’ total score was 5.22±1.34 point, there were no statistical differences between the two groups’ scores (p=0.332).

Characteristics of the study population.

| Total | Semen Results | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men with normozoospermia | Men with dysspermia | |||

| Age (mean±SD) | 30.81±5.90 | 30.60±5.61 | 31.22±6.40 | 0.168** |

| Educationn (%) | 0.070* | |||

| Primary | 420 (32.0%) | 257 (30.2%) | 163 (35.5%) | |

| Secondary | 529 (40.4%) | 345 (40.5%) | 184 (40.1%) | |

| Higher | 362 (27.6%) | 250 (29.3%) | 112 (24.4%) | |

| BMI (mean±SD) | 25.72±3.75 | 25.59±3.65 | 25.97±3.94 | 0.100** |

| BMI (kg/m2)n (%) | 0.272* | |||

| <25 | 581 (44.4%) | 387 (45.4%) | 194 (42.3%) | |

| ≥25 | 730 (55.6%) | 465 (54.6%) | 265 (57.7%) | |

| Smoking (any amount)n (%) | 0.662* | |||

| No | 430 (32.8%) | 283 (33.2%) | 147 (32.0%) | |

| Yes | 881 (67.2%) | 569 (66.8%) | 312 (68.0%) | |

| Alcohol intake (any amount)n (%) | 0.162* | |||

| No | 943 (72.0%) | 602 (70.7%) | 341 (74.3%) | |

| Yes | 368 (28.0%) | 250 (29.3%) | 118 (25.7%) | |

| Coffee intake (cups/day)n (%) | 0.848* | |||

| ≤3 | 424 (32.4%) | 274 (32.2%) | 150 (32.7%) | |

| >3 | 887 (67.6%) | 578 (67.8%) | 309 (67.3%) | |

| Exercise (regularly)n (%) | 0.594* | |||

| No | 1116 (85.1%) | 722 (84.7%) | 394 (85.8%) | |

| Yes | 195 (14.9%) | 130 (15.3%) | 65 (14.2%) | |

| Cell phone (years) (mean±SD) | 12.38±3.98 | 12.40±3.92 | 12.33±4.11 | 0.464** |

| Cell phone (years)n (%) | 0.984* | |||

| <10 | 206 (15.8) | 134 (15.7%) | 72 (15.7%) | |

| ≥10 | 1105 (84.2%) | 718 (84.3%) | 387 (84.3%) | |

| Tight-fitting underwear (regularly)n (%) | 0.004* | |||

| No | 282 (21.6%) | 119 (25.9%) | 163 (19.1%) | |

| Yes | 1029 (78.4%) | 340 (74.1%) | 689 (80.9%) | |

| Sauna (regularly)n (%) | 0.121* | |||

| No | 579 (44.2%) | 363 (42.6%) | 216 (47.1%) | |

| Yes | 732 (55.8%) | 489 (57.4%) | 243 (52.9%) | |

| Total risk scores (mean±SD) | 5.22±1.34 | 5.26±1.34 | 5.16±1.36 | 0.332** |

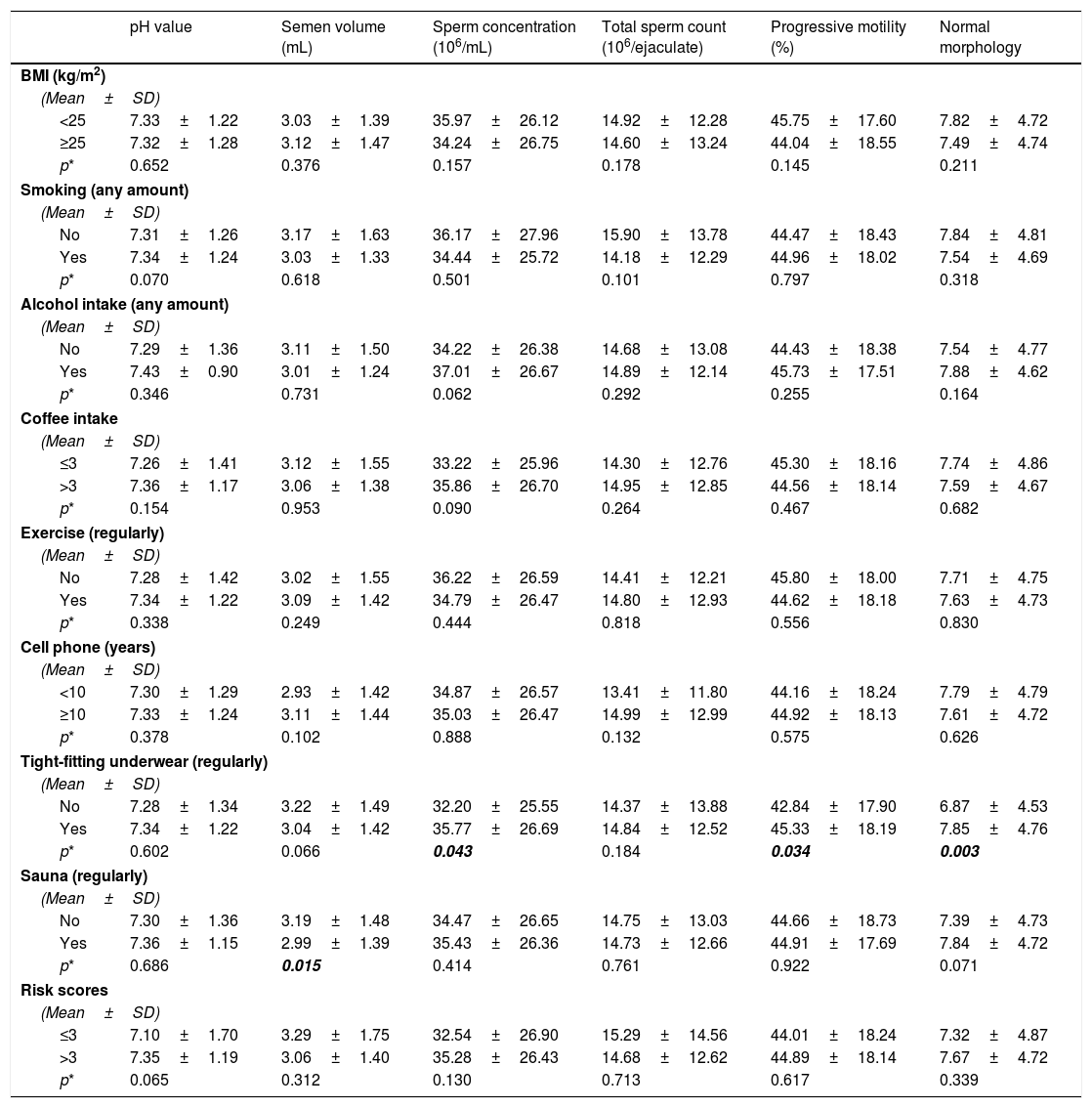

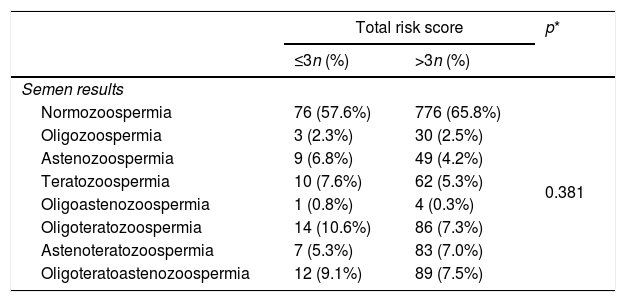

As seen in Table 2, while going to a sauna regularly was negatively related to semen concentration, wearing tight underwear was also related to both lower motility, normal morphology and semen concentration (p<0.05). All other examined lifestyle factors were not related with any of the examined semen parameters. After ROC curve analysis, a cut-off point for ‘risky lifestyle for infertility’ was set at more than 3 points. It was detected that having 3 more or fewer points was not related to any type of semen parameters and the results of a spermiogram (Tables 1 and 3).

Lifestyle factors (BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, coffee consumption, exercise, cell phone, sauna and tight underwear) linked to analyzed semen parameters.

| pH value | Semen volume (mL) | Sperm concentration (106/mL) | Total sperm count (106/ejaculate) | Progressive motility (%) | Normal morphology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| (Mean±SD) | ||||||

| <25 | 7.33±1.22 | 3.03±1.39 | 35.97±26.12 | 14.92±12.28 | 45.75±17.60 | 7.82±4.72 |

| ≥25 | 7.32±1.28 | 3.12±1.47 | 34.24±26.75 | 14.60±13.24 | 44.04±18.55 | 7.49±4.74 |

| p* | 0.652 | 0.376 | 0.157 | 0.178 | 0.145 | 0.211 |

| Smoking (any amount) | ||||||

| (Mean±SD) | ||||||

| No | 7.31±1.26 | 3.17±1.63 | 36.17±27.96 | 15.90±13.78 | 44.47±18.43 | 7.84±4.81 |

| Yes | 7.34±1.24 | 3.03±1.33 | 34.44±25.72 | 14.18±12.29 | 44.96±18.02 | 7.54±4.69 |

| p* | 0.070 | 0.618 | 0.501 | 0.101 | 0.797 | 0.318 |

| Alcohol intake (any amount) | ||||||

| (Mean±SD) | ||||||

| No | 7.29±1.36 | 3.11±1.50 | 34.22±26.38 | 14.68±13.08 | 44.43±18.38 | 7.54±4.77 |

| Yes | 7.43±0.90 | 3.01±1.24 | 37.01±26.67 | 14.89±12.14 | 45.73±17.51 | 7.88±4.62 |

| p* | 0.346 | 0.731 | 0.062 | 0.292 | 0.255 | 0.164 |

| Coffee intake | ||||||

| (Mean±SD) | ||||||

| ≤3 | 7.26±1.41 | 3.12±1.55 | 33.22±25.96 | 14.30±12.76 | 45.30±18.16 | 7.74±4.86 |

| >3 | 7.36±1.17 | 3.06±1.38 | 35.86±26.70 | 14.95±12.85 | 44.56±18.14 | 7.59±4.67 |

| p* | 0.154 | 0.953 | 0.090 | 0.264 | 0.467 | 0.682 |

| Exercise (regularly) | ||||||

| (Mean±SD) | ||||||

| No | 7.28±1.42 | 3.02±1.55 | 36.22±26.59 | 14.41±12.21 | 45.80±18.00 | 7.71±4.75 |

| Yes | 7.34±1.22 | 3.09±1.42 | 34.79±26.47 | 14.80±12.93 | 44.62±18.18 | 7.63±4.73 |

| p* | 0.338 | 0.249 | 0.444 | 0.818 | 0.556 | 0.830 |

| Cell phone (years) | ||||||

| (Mean±SD) | ||||||

| <10 | 7.30±1.29 | 2.93±1.42 | 34.87±26.57 | 13.41±11.80 | 44.16±18.24 | 7.79±4.79 |

| ≥10 | 7.33±1.24 | 3.11±1.44 | 35.03±26.47 | 14.99±12.99 | 44.92±18.13 | 7.61±4.72 |

| p* | 0.378 | 0.102 | 0.888 | 0.132 | 0.575 | 0.626 |

| Tight-fitting underwear (regularly) | ||||||

| (Mean±SD) | ||||||

| No | 7.28±1.34 | 3.22±1.49 | 32.20±25.55 | 14.37±13.88 | 42.84±17.90 | 6.87±4.53 |

| Yes | 7.34±1.22 | 3.04±1.42 | 35.77±26.69 | 14.84±12.52 | 45.33±18.19 | 7.85±4.76 |

| p* | 0.602 | 0.066 | 0.043 | 0.184 | 0.034 | 0.003 |

| Sauna (regularly) | ||||||

| (Mean±SD) | ||||||

| No | 7.30±1.36 | 3.19±1.48 | 34.47±26.65 | 14.75±13.03 | 44.66±18.73 | 7.39±4.73 |

| Yes | 7.36±1.15 | 2.99±1.39 | 35.43±26.36 | 14.73±12.66 | 44.91±17.69 | 7.84±4.72 |

| p* | 0.686 | 0.015 | 0.414 | 0.761 | 0.922 | 0.071 |

| Risk scores | ||||||

| (Mean±SD) | ||||||

| ≤3 | 7.10±1.70 | 3.29±1.75 | 32.54±26.90 | 15.29±14.56 | 44.01±18.24 | 7.32±4.87 |

| >3 | 7.35±1.19 | 3.06±1.40 | 35.28±26.43 | 14.68±12.62 | 44.89±18.14 | 7.67±4.72 |

| p* | 0.065 | 0.312 | 0.130 | 0.713 | 0.617 | 0.339 |

Semen variables amongst participants with ≤3 points with respect to >3 points.

| Total risk score | p* | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤3n (%) | >3n (%) | ||

| Semen results | |||

| Normozoospermia | 76 (57.6%) | 776 (65.8%) | 0.381 |

| Oligozoospermia | 3 (2.3%) | 30 (2.5%) | |

| Astenozoospermia | 9 (6.8%) | 49 (4.2%) | |

| Teratozoospermia | 10 (7.6%) | 62 (5.3%) | |

| Oligoastenozoospermia | 1 (0.8%) | 4 (0.3%) | |

| Oligoteratozoospermia | 14 (10.6%) | 86 (7.3%) | |

| Astenoteratozoospermia | 7 (5.3%) | 83 (7.0%) | |

| Oligoteratoastenozoospermia | 12 (9.1%) | 89 (7.5%) | |

This study focused on the possible relationship of eight lifestyle factors and semen quality using the semen parameters: sperm count, motility and morphology. Although evidence from epidemiological studies on these factors and semen parameters is still inconsistent and inconclusive, obesity is perhaps the only lifestyle factor which has been shown to adversely affect semen quality with any certainty. There has been a hypothesis that male obesity could induce endocrine disorders and these disorders may affect the spermatogenesis.9 The studies showed that men with BMI>25kg/m2 had the higher risk of oligozoospermia, astenozoospermia10 and whereas a meta-analysis of 31 studies found no evidence of an association between increased BMI and semen parameters.12

There is still no current agreement on the effect of smoking on the conventional semen parameters and sperm DNA damage as with other lifestyle factors13,14. The last meta-analysis in literature, according to our knowledge, included 57 cross-sectional studies with 29,914 participants on the association between socio-psycho-behavioral factors and male semen quality, showed that only smoking decreased semen volume and the total sperm count, but the effect of stress and BMI on semen volume, the effect of age, alcohol and coffee consumption on sperm density, the effect of age and alcohol on the total sperm count, the effect of alcohol and coffee consumption on sperm progressive motility, and the effect of age, alcohol and coffee consumption on sperm morphology were also uncertain (p>0.05)8; but other authors did not find any effect on these sperm parameters.15,16

The association between alcohol intake and semen quality was detected in numerous studies. It was shown that alcohol intake could cause testicular atrophy and had an adverse effect on semen parameters14,17 due to the well-known toxic effect of alcohol and its metabolites which may cause oxidative stress.18 A meta-analysis by Ricci et al. included 15 cross sectional studies with 16,935 men showed that the effect of alcohol intake on semen parameters were dose dependent.19 It was discussed that moderate consumption did not adversely affect semen parameters; sperm motility and morphology was better in occasional drinkers due to the polyphenols, which were known to have strong therapeutic and cell protective potential20 and daily or heavy drinking has a detrimental affect on semen quality. Despite these results; it was reported that alcohol consumption did not appear to significantly affect sperm parameters.21,22

There have been contradictory results on caffeine intake and semen quality. While some reports could not show an association23; others showed that dysspermia risk increased with caffeine intake11,24 especially with the ≥3 cups per day25,26 by altering the Sertoli Cells’ oxidative profile.27

Exercise has been associated with improved semen quality in a few studies.11,28,29 In a study, sedentary infertile men applied a moderate aerobic exercise training program. After 24 weeks, it was shown that all semen parameters were statistically increased from the baseline parameters.30 Despite these results, no relationships were found between physical activity and normal/abnormal sperm parameters except sperm motility. It was shown that men who had vigorous-intensity physical activity had a higher percentage of immotile sperm than who had moderate-intensity physical activity.31

There are limited studies on the effect of saunas/high temperature, wearing tight underwear and using cell phones on semen quality. A systematic review with only 6 observational studies, two prospective controlled trials and no randomized controlled trials about scrotal cooling showed that sperm count, motility and morphology improved with scrotal cooling but the evidence of the effect of scrotal cooling on male fertility was limited.32 It was shown that cell phones used for a long time especially for more than 10 years11 and carrying these phones in a hip pocket or on a belt33 negatively affected semen quality in limited studies. A study by Yang et al. demonstrated that wearing tight underwear was not associated with semen quality25; it was assessed that men who wore boxer shorts had a risk of sperm morphology abnormalities; DNA damage in other reports11.

According to our results, we only found that there was a relationship between wearing tight-fitting underwear regularly and dysspermia (p=0.004) with decreasing sperm concentration, motility and normal morphology (p<0.05). Incidentally, going to a sauna regularly was also associated with lower sperm concentration (p=0.015). All other examined lifestyle factors did not appear to be associated with semen parameters. Although the percentage of alcohol non-drinkers (72.0%) were more than the percentage of the alcohol drinkers (28.0%) in our study, there was no statistical relationship between drinking alcohol regularly and dysspermia; and we did not find any significant association of normal semen quality with never drinking alcohol. In addition, although the percentage of not exercising regularly (85.1%) was more than the percentage of exercising regularly (14.9%), there were no statistical relationship between not exercising regularly and dysspermia.

In recent years there has been more attention on the impact of lifestyle factors on health especially fertility. Kaya et al. showed that health-promoting lifestyle education for correcting unhealthy lifestyle factors in women with unexplained infertility was found to be effective in increasing the success rates of assisted reproduction treatment.34 Several studies also examined the effect of the factors on sperm parameters, but their results are inconsistent. In many studies it was estimated that these factors influenced semen parameters by itself. To show the compound effect of these factors, Wogatzky et al. designed a study and scored BMI>25, age>50, coffee intake>3 cups per day, sexual abstinence (>2 days), ejaculation frequency (<4x month) with one point each. 2 points were set as a cut-off level and men who had more than 2 points were classified as unhealthy. They found that unhealthy males had lower sperm quality.20 In our study the lifestyle factors were coded positively if the BMI was ≥25; he smoked every day; drank any amount of alcohol; drank more than 3 cups of coffee a day; did not do any type of exercise regularly; wore tight-fitting underwear regularly; went to a sauna regularly, or used ca ell phone≥10 years, during the 3 month window before semen collection. We found that the total risk score for all participants was 5.22±1.34 but there was no significant difference between men with normozoospermia and dysspermia (p=0.332). 3 points were calculated as a cut-off point for ‘risky lifestyle for infertility’. Despite the relation between being over the cut-off point and having lower sperm quality as in the study by Wogatzky et al.,49 having 3 more or fewer points was not related to any type of semen parameters and the results of a spermiogram in our study.

The first limitation of this study was that the participants were not randomly selected from the general population. The men were from an andrology clinic so we could not examine a sample of the general male population. To overcome this disadvantage we separated the participants as men with normal semen parameters or with dysspermia. The second limitation was the fact that only one semen sample was evaluated for each participant by only conventional semen analysis techniques. The third limitation was that we did not obtain validated results on exposure to alcohol and smoking. Moreover, we cannot conclude the caffeine intake only from coffee consumption because caffeine is also present in many products.

ConclusionThis study showed that smoking, alcohol or caffeine consumption, using a cell phone, and not exercising regularly, did not affect semen quality using conventional semen parameters. Despite both our results and inconsistent reports in literature; clinicians should give the advice about not smoking, not consuming alcohol, not wearing tight underwear, and having a body mass index (BMI) of ≤25, doing exercise regularly, using cell phones less and not going to saunas to the infertile or subfertile male patients at least during the period of trying to achieve achieving a pregnancy due to the influence of these factors on semen production. Thus, the modification of lifestyle can prevent infertility, improved possibility to conceive spontaneously or optimize the chances of conception with greater awareness and recognition of the possible impact of these lifestyle factors. Better designed studies, with larger sample sizes using conventional semen analysis with sperm DNA analysis methods, should be planned to identify the possible effect of lifestyle factors on semen quality.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingNone.

Conflict of interestThere was no conflict of interest.

Thanks are given to Seyda Cakan, Eshisehir State Hospital Embryology Laboratory, for helping to collect the datas and Muzaffer Bilgin, Eskisehir Osmangazi University, Medical Faculty, Department of Bioistatistics, for analyzing the data statistically.