In 2002, Steve Wilson pioneered new procedures for alternative placement of reservoirs for inflatable prostheses in patients who have suffered damage to the space of Retzius following pelvic surgery or obliteration of the transversalis fascia by mesh hernia repair. Since then, surgical techniques and tools for ectopic reservoir placement have gradually gained acceptance to minimize palpability, and the risk of visceral and vascular lesions for high risk patients has been all but eliminated. Lockout valves and high submuscular placement techniques are now recommended, and reports of vascular, bowel or bladder injuries are uncommonly rare. While surgeons continue their search for safer and more effective placement methods, new skills and instruments are constantly being introduced to make recommendations to minimize complications and provide safety and functionality. Additional studies and comparisons of techniques are needed to achieve a consensus of best practice for reservoir placement solutions.

En 2002, Steve Wilson fue el precursor de nuevos procedimientos para la colocación alternativa de reservorios para prótesis inflables en los pacientes que habían sufrido daños en el espacio de Retzius tras cirugía pélvica u obliteración de la fascia transversalis por reparación de hernia con malla. Desde entonces, han ido ganando aceptación las técnicas y herramientas quirúrgicas para colocación de reservorio ectópico, a fin de minimizar la palpabilidad, habiéndose eliminado prácticamente el riesgo de lesiones viscerales y vasculares para pacientes de alto riesgo. Hoy en día se recomiendan las válvulas de bloqueo y las técnicas de colocación submuscular alta, siendo excepcionalmente raros los informes sobre lesiones a nivel vascular, intestinal o en la vejiga. A pesar de que los cirujanos siguen investigando en busca de métodos de colocación más seguros y efectivos, se están introduciendo constantemente nuevas competencias e instrumentos en aras de realizar recomendaciones para minimizar las complicaciones y aportar seguridad y funcionalidad. Son necesarios más estudios y comparaciones sobre técnicas para lograr un consenso acerca de la mejor práctica sobre soluciones de colocación de reservorios.

Implantation of the three-piece inflatable penile prosthesis (IPP) is the gold standard treatment for erectile dysfunction (ED) after failure of first- and second-line therapies.1 IPPs are reliable devices with more than 95% 5-year and 80% 10-year mechanical survival rates.2 In the hands of experienced surgeons, penile prosthesis surgery results in high patient and partner satisfaction rates and few complications.

For more than 45 years, IPP reservoirs have been placed traditionally in a retropubic location in the Space of Retzius (SR) by blind puncture through the transversalis fascia. This technique can be challenging for several reasons. Some patients are at risk from the rapid development of minimally invasive robotic assisted procedures that usually obliterate the SR or from prior extensive pelvic or inguinal surgery which distorts anatomy within the pelvis or inguinal ring. Since life-threatening complications (viscera or vessel injury) can result from SR reservoir placement, alternative methods should be considered.

Multiple techniques have been described to place the reservoir with reliable techniques, including intraperitoneal, scrotal, abdominal wall, lateral retroperitoneum, and even staged placement in the pelvis at the initial pelvic surgery. Wilson and col.3,4 were the first to describe the ectopic reservoir placement, by which the reservoir from an IPP and/or from an artificial urinary sphincter may be placed within the anterior abdominal wall, posterior to the rectus abdominal muscle and anterior to the transversalis fascia via the external inguinal ring without a separate counter incision. Acceptance was limited because of low positioning and poor patient satisfaction due to palpability and visibility of the component. Several modifications successfully reduced device palpability and risk for herniation through the external inguinal ring.

More reconstructive and prosthetic surgeons are opting for Alternative Reservoir Placement (ARP) as a norm even for low risk patients, and they question whether the actual paradigm of routine reservoir placement in the SR should be changed.

To whom and howHigh-risk/complex patientA surge of minimally invasive surgery is currently leading to encounters with transperitoneal Robotic-Assisted Laparoscopic Prostatectomy (RALP) patients, during which the lower peritoneum is incised and reflected away from the retropubic space. Re-peritonealisation of the Retzius space is unpredictable and increases the risk of inadvertent entry into the peritoneum if the transversalis fascia is blindly perforated during conventional IPP reservoir placement.5

The traditional retropubic approach may also be hazardous in selected patients with previous pelvic surgery, such as renal transplant, radical cystectomy, colostomy, neobladder, and/or pelvic radiation.

Avoiding transversalis fascia perforation may also be beneficial for patients with a history of mesh inguinal hernia repair.6 Since 27% of men will have inguinal hernia repair surgery during their lifetime, assessment of the external inguinal ring is recommended as part of the preoperative evaluation.7

Patients with a history of surgical procedures that have obliterated the bilateral inguinal ring with meshed hernia repair can have successful reservoir placement by entering through the midline suprapubic area below the linea alba (Egydio personal experience).

Intraoperative considerations for alternative reservoir placementBefore starting to develop the space for the reservoir, the surgical table should be positioned in the Trendelenburg position and the bladder emptied, whether SR or ARP is used.

A paediatric Deaver retractor may be used to lift the incision, and finger dissection is used to peel fibres upward off the pubic bone toward the external inguinal ring. Before piercing the transversalis fascia, the index finger is turned cephalad to dissect a space for the reservoir between the rectus abdominis muscle and transversalis fascia. If finger advancement is not enough, an array of instruments can be used to advance and deploy the reservoir to a more cephalad position. A bladder catheter is inserted up to the umbilicus level, and the balloon is inflated up to 100 cc to dilate the virtual space, while the penile implant is prepared on a separate table. If finger dissection is unsuccessful, a long ring forceps is introduced into this space, and the arms are spread in alternating anterior-posterior and medial-lateral directions to lift the rectus muscle off the transversalis fascia. During dissection, the pubic tubercle is used as a fulcrum to angle the forceps in the anterior direction. With this approach, the possibility of straying from the correct dissection plane can be minimized.

Device improvementsDue to advanced modifications, IPP components are among the most reliable medical devices available. Malfunction rates have been decreasing over a period of 10 years, and existing 5-, 10-, and 15-year data predict a mechanical survival rate of 94.7%, 79.4%, and 71% respectively.8–10 While most existing data originated from older studies, modern devices have a 10-year mechanical survival rate closer to 90%.10

Advances in mechanical reliability have been focused on cylinders, pumps, and tubing, but reservoirs have also been improved. The development of seamless, spherical reservoirs in 1978 with kink resistant tubing and elimination of the internal reinforcing rod or stem in 1983 contributed to longer survival rates.11

In 2000, a reservoir lockout valve was added to the Coloplast® (Coloplast manufacturing, Minneapolis, MN, USA), thereby reducing the auto-inflation rate from 11% for original reservoirs to 1.3% for those equipped with lockout valves.3 In 2006, AMS® (Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA) developed a lockout valve incorporated into the pump which prevents auto-inflation of the device.12

Modifications in IPP components were also made to provide better concealment, especially for reservoirs placed ectopically. In 2010, AMS® introduced the Conceal™ reservoir with a flat configuration as compared to traditional spherical reservoirs when filled with saline. However, FDA approval for ectopic placement of IPP reservoirs in anatomically compromised patients was only granted in 2015 to the Coloplast® Cloverleaf™ reservoir, which has a bellows configuration that assumes a flat shape when partially filled but maintains a cylindrical shape when full. This reservoir has an internal lock-out valve to minimize auto-inflation resulting from sudden changes in abdominal pressure.5

Evolution of reservoir placementFor decades, the standard and ideal IPP reservoir placement was the SR, accessed via blunt perforation through the transversalis fascia at the floor of the inguinal canal to provide easy access to a non-palpable, low pressure space. Due to the difficulty of this manoeuvre, Henry and coll.13 described a method for safe reservoir placement by putting patients in the Trendelenburg position, so that bladder and bowels fall away from the inguinal ring and the external inguinal vein becomes decompressed. The index finger is used to identify the external inguinal ring by palpating over the periosteum of the pubic bone and to perforate the transversalis fascia for reservoir.13 Tomada's manoeuvre implies the additional use of a bladder catheter balloon to safely dilate the SR without disturbing the external inguinal ring. In this way it is possible to accommodate the reservoir with adequate space while providing haemostasis and preventing reservoir herniation.14

Alternative placement of reservoirs was first popularized in Germany by Professor Schreiter almost 30 years ago5 when reservoirs did not have lockout valves. Reservoir placement in the peritoneal cavity avoided capsular formation to prevent undesired auto-inflation events. Intraperitoneal location is not without potential complications, such as small bowel obstruction, bowel compression, laceration, or erosion.15,16 Therefore, secondary subcostal incisions for epigastrium placement or direct incisions through the rectus fascia in the midline suprapubic region were the most common logical alternatives to avoid surgically compromised pelvises.17

Concern about compromised pelvises began to grow in proportion to the number of pelvic altering surgeries, especially for RALP. To avoid extensive scarring of the prevesical space and diminish increased risks of visceral and vascular injury, several alternative reservoir locations were used, involving placement between the transversus abdominis muscle anteriorly and the transversalis fascia posteriorly, rectus abdominis muscle anteriorly and transversalis fascia posteriorly, or subcutaneous below the Scarpa's fascia.18–20

Wilson published the first description of ectopic location in patients with altered pelvic anatomy.3 He introduced the reservoir by piercing the back wall of the inguinal canal with the finger and pushing the component into the space anterior to the transversalis fascia below the abdominal wall muscles. This technique did not gain broad acceptance among prosthetic surgeons mainly due to resultant reservoir palpability in the groin and potential for herniation toward the high scrotum. In his own words, blunt manual dissection was difficult and painful for the surgeon. To maintain the advantages of ectopic placement while sparing the finger, reservoirs could be placed either posterior or anterior to the transversalis fascia in a more cephalad position. A long nasal speculum is used to create a space by spreading the paddles. A 12 Hegar dilator was then advanced to develop the space.21,22

Morey and coll. also contributed to reduction of reservoir palpation and elimination of subsequent herniation by popularizing the high submuscular approach with a 14-in. Foerstar lung clamp from a penoscrotal incision to develop the space and place the reservoir even more cephalad and under the rectus muscle.19,23

To deploy the reservoir, an array of instruments can be used, from Perito's paediatric Yankour to sponge stick or ring forceps. Recently, a new elongated clamp with double articulation joints, that prevent enlargement of small implant incisions when spreading with a ridged, toothed distal surface, was specifically designed for high submuscular reservoir placement with input from Wilson and Perito.5

Safety and complications of reservoir placement techniquesSpace of Retzius placementTraditional placement of reservoirs has been associated with rare but sometimes serious complications, including mispositioning into the peritoneum, reservoir herniation, ureteral obstruction, injury to the bladder, bowel, or vascular injuries.24–28

The danger of blind placement of reservoirs in the SR is best understood by cadaveric studies that revealed the average proximity of the inguinal ring to the bladder to be 2.6cm when full and 6.5cm when empty29 – a clear indication of the importance of bladder decompression before reservoir placement to avoid bladder injury.

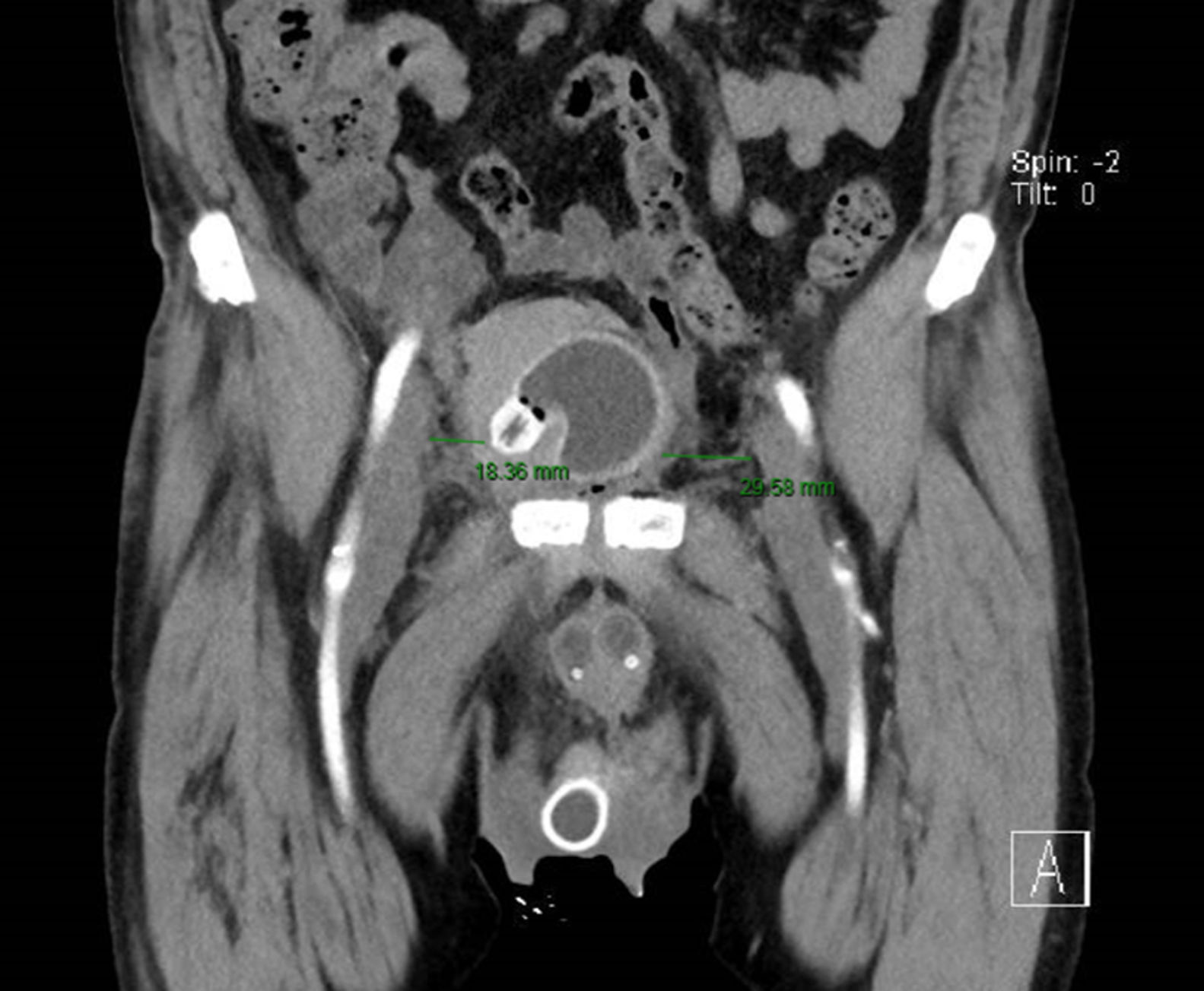

Risk factors for bladder injury are pelvic surgery and radiation. Patients with reservoir-associated bladder injury usually occur together with gross haematuria, storage symptoms of the lower urinary tract or IPP infection. In one study, reservoir erosion and migration, while rare, were documented in a total of 0.4% of patients, with six cases into the bladder and two into an ileal conduit.30 Small bowel obstruction and intestinal fistula are also extremely rare and share the same risk factors as bladder injury. Inguinal hernias containing the bowel have been reported to occur after reservoir placement.11 Vascular injuries are also uncommon but potentially devastating. As demonstrated in cadaver studies, deep dissections lateral to the inguinal ring should be avoided as the iliac vein is 3.23cm away.29 The iliac vein can be even much closer to the reservoir than currently advocated (Fig. 1).

Partial venous obstruction and subsequent edemas of the lower limbs often result from inflated reservoirs, while deep venous thrombosis and direct injury to the external iliac vein or branches, such as the inferior epigastric, external superficial pudendal, or cremasteric vessels, rarely occur.31 A strategy to avoid vascular complications consists in placing patients in the Trendelenburg position to achieve greater distance of the external iliac vein from the inguinal ring and ensure that adequate space has been created to eliminate compression to the adjacent venous structures.11

Less serious complications can also occur with SR placement, namely auto-inflation. The introduction of lock-out mechanisms has reduced the incidence of auto-inflation to <1%.5

Reservoir migration through the inguinal canal is unusual with a range of 0.9–1.2%.18 Also uncommon is reservoir inguinal herniation. As mentioned before, Tomada's manoeuver can decrease the incidence of herniation.32 Surgeons should know there are several risk factors: obesity, respiratory disorders, smoking, and patulous external inguinal rings, as well as penoscrotal approach.24,33 Though rare, herniation can result from insufficient tubing between the pump and reservoir and may be associated with coughing or vomiting. During the early postoperative period, patients should be counselled to avoid strenuous physical activity.

Alternative reservoir placementMinimally invasive surgery, like transperitoneal laparoscopic prostatectomy or cystectomy (robotic assisted or not), has gained popularity but may result in anatomical changes to the SR, thereby creating special challenges for reservoir placement.

In a recent survey, implant surgeons stated that RALP makes traditional SR placement more difficult because of scar formation and adhesions that occur following prostate removal after failed reconstruction of the peritoneal veil. Ectopic placement is more advantageous in these anatomical environments and complications are rare.34 In this same survey, 97% of the responders recommended these techniques be included in surgeon training courses.

A new era began with the ectopic reservoir placement below the muscles in the abdominal wall introduced by Wilson and coll. in 2001.3 However, as already stated, this method failed to gain popularity due to reservoir palpability and risk of herniation.

With the introduction of flat reservoirs and high submuscular placement, palpability varied from 3.4% to 58% with ARP, and the highest percentage occurring shortly after surgery.22,23,34,35 The role of body mass index (BMI) to predict the risk of reservoir palpability is controversial. Some studies found that rectus abdominis muscle and the overlying abdominal tissue are sufficient to mask reservoir palpability in almost all ranges of BMI,23 while others report that palpability disappears in 80% of the patients with higher BMI after capsule formation three months post-surgery.35

Reservoir palpability was reported only to be between 0% and 1.3% and did not affect patient satisfaction nor was it a significant factor for revision surgery as were.22,23,36,37

Patients have higher abdominal musculature pressure and theoretically should have a higher incidence of herniation. However, this only occurred with up to 1.4% of patients undergoing ectopic reservoir placement anterior to transversalis fascia.18 The same principles of balloon dilation used in Tomada's manoeuvre kept the reservoir in high submuscular position. Digital and ring forceps aided to minimize the possibility of reservoir herniation without the need to apply a purse string suture around the inguinal ring.33,36 Recent surgeries did not reveal any cases requiring revision for herniation or auto-inflation, again suggesting these newer IPP flat reservoirs can be placed in alternative locations without concern of being subjected to higher pressures.18

Morey and coll.19 were the first to report on the technique and the outcome of high submuscular reservoir placement. No major vascular, bladder, bowel or ureteral injuries were reported. Posterior updates with ongoing experience and refinement of technique revealed complications and surgical revision rates similar in frequency to SR but minor in nature, with negligible risks for visceral or vascular injury in the high submuscular group.23,38

This favourable risk profile was also observed in a retrospective analysis of 2700 penile implant reservoirs placed with the aid of a nasal speculum posterior to fascia transversalis in patients with virgin pelvis or anterior to fascia transversalis in patients with previous pelvic surgery. No vascular injuries and only two cases of bladder injuries were reported.22 These lacerations occurred because full bladder was not recognized prior to speculum passage. Although ARP is a safe and mechanically reliable approach, even for men with prior pelvic surgery, there are other risks, such as reservoir leakage, tubing torsion, muscle discomfort and unintended reservoir malposition which may require surgical revision.

A recent 5-year multi-institutional experience reviewed 974 IPPs, including 612 ARPs and 362 SRs.37 There were no significant differences in complication rates between groups (2% in the ARP group and 1.3% in the SR group). The most common complication in the ARP group was reservoir leakage (five cases, 0.8%). Upon removal, all reservoirs with leakage had been folded and pinpoint holes were observed at the apex through which leakage, associated with underfilling at the time of the implantation, had occurred. The use of instruments not designed specifically for ectopic placement of the reservoir can cause damage during placement and contribute to reservoir leakage.39 Therefore, the authors strongly recommend filling the Conceal reservoir with at least 80mL of saline solution to prevent premature device failure.

Discomfort or pain at the anterior abdominal wall muscles adjacent to the reservoir was also reported by three ARP patients in this study. In two cases the reservoir was placed in the submuscular area and revision was done by the same penoscrotal incision. The reservoir in the third case was in the sub-Scarpa's space and required a counter incision for deeper reservoir placement three months after the initial surgery. Torsion of the tubing occurring in three cases of ARP and in one of SR was attributed to both caudal migration and twisting in the cord caused by increased pressures exerted by the abdominal wall.37

Another commonly expressed concern for the alternative reservoir location is the difficulty of removing or exchanging the reservoir at the time of an eventual surgical revision. Though theoretically an easier procedure, there is a potential for unintended placement into spaces other than the actual high submuscular position.

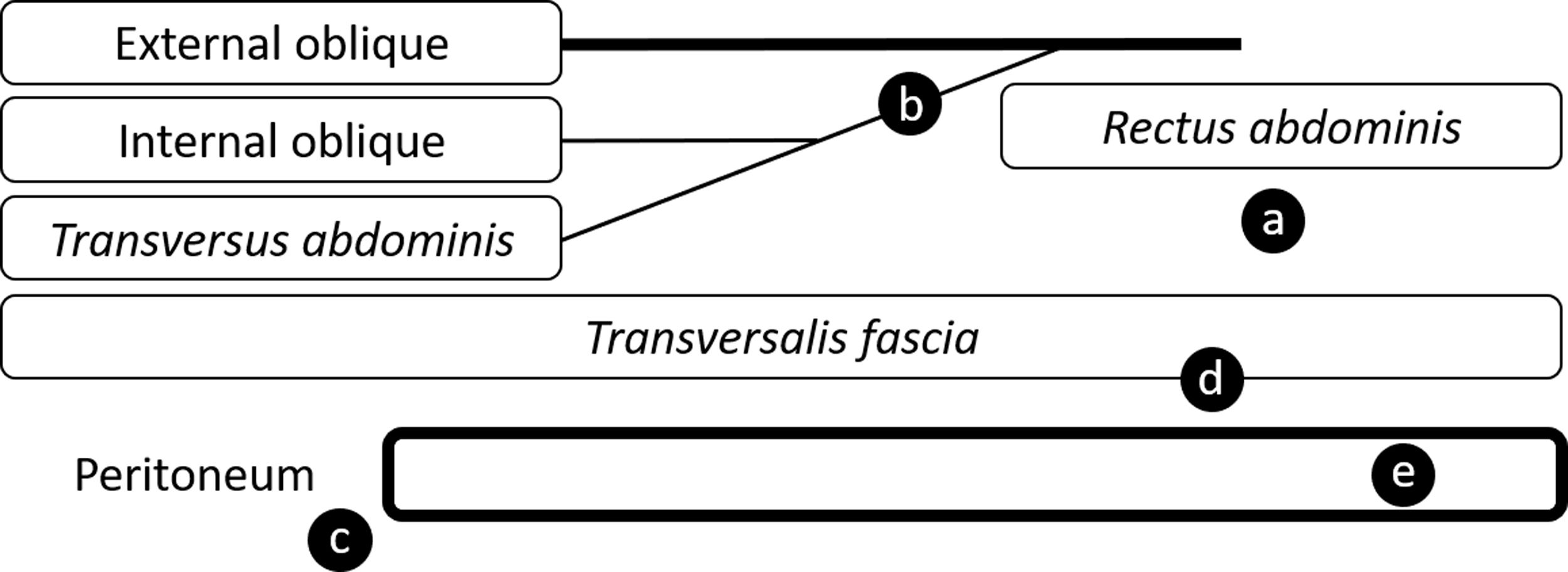

Ziegelmann and coll.40 positioned 20 IPP reservoirs in cadavers in a high submuscular location without difficulty or concern for inadvertent mispositioning and found that this attempt could result in variable final positions: deep to rectus muscle (35%), between the external and internal oblique fascia (45%), retroperitoneal space (10%), preperitoneal (5%), and intraperitoneal (5%) (Fig. 2). Since the high submuscular technique has a longer length of tubing which provides a longer probability for potential entrapment of bowel or other structures, an intraperitoneal or retroperitoneal placement may increase the risk for potentially catastrophic complications, especially for patients with prior abdominal or pelvic surgery.40 However, in most studies, intraperitoneal placement has been reported to be <1% in the hands of high-volume surgeons.16,23,37,41

Schematic of possible reservoir locations within the abdominal wall (adapted from Ziegelmann and coll.40). (a) Anterior to transversalis fascia and posterior to rectus abdominis. (b) Posterior to external oblique fascia. (c) Retroperitoneal. (d) Preperitoneal. (e) Intraperitoneal.

Variable reservoir placement using the high submuscular technique depends on specific anatomic factors of the inguinal canal. The creation of new space may vary depending on the extent of abdominal wall protrusion, canal angulation, location of fusion of various abdominal wall layers, and strength of fascial planes. It is not surprising to observe significant variability in reservoir locatio.40

Another criticism is the long distance between the reservoir and the penoscrotal incision at the time of IPP revision or removal. Submuscular reservoir placement does not violate fascial planes, and firm traction on the tubing often suffices to retrieve a deflated IPP reservoir, virtually eliminating injury to pelvic viscera and major vasculatur.6 If the reservoir does not descend, removal can be attempted using a counter incision guided through palpation, intraoperative ultrasound, or review of preoperative CT imaging.18 If not infected, the reservoir can be emptied. Proximal cutting of the tube allows it to retract and stay in place, while other reservoirs can be placed in contralateral ectopic location – the “drain and retain” strategy.42

ConclusionsA higher percentage of patients today are complex cases which carry a significant risk of bowel, bladder, and vascular injuries during reservoir placement. The constant pursuit of a safer and more efficacious zone for this surgical step has led to steady advances in surgical technique and device improvements. ARP provides unique benefits over traditional placement in the retropubic space. While maintaining excellent function and aesthetic value, ARP offers several safety advantages, especially for patients with history of pelvic surgery and/or radiation.

In comparison to the SR reservoir placement, ARP has gained increased popularity due to less complications and comparable satisfaction. Although the initial strategy was for high risk patients, experience has provided important clinical evidence that strongly supports the safety and continued expansion of ARP, and, the high submuscular alternative placement strategy can be performed in nearly all patients.

In conclusion, ARP is a safer method of reservoir placement which offers quality-of-life enhancing surgery to patients and encourages surgeons to consider ARP as a first option for reservoir placement.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that for this investigation no experiments were carried out on humans and/or animals.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appears in this article.

Conflict of interestAuthors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.