Isavuconazole, a triazole-class antifungal, is effective and safe for both primary treatment and salvage therapy in a variety of fungal infections. This article reviews recent knowledge on the role of this antifungal in the treatment of mucormycosis and breakthrough invasive fungal infections (bIFI) during antifungal therapy. Isavuconazole has demonstrated favorable clinical outcomes and a good safety profile in various patient populations with mucormycosis, including those with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus or severe immunosuppression. Particularly noteworthy is the fact that drug interactions in patients with mucormycosis, where a solid organ transplant was a predisposing factor, have been effectively managed. In the treatment of bIFIs, the use of isavuconazole requires a thoughtful reflection about the fungal species involved and their susceptibility profiles. This is highly dependent on the antifungal agent administered before the onset of bIFI. Early diagnosis and appropriate antifungal therapy are essential to improve outcomes in patients with mucormycosis and bIFIs. Isavuconazole represents a valuable option for managing these complex infections.

El isavuconazol, un fármaco antifúngico de la clase de los triazoles, es eficaz y seguro tanto para el tratamiento primario como para la terapia de rescate de diversas infecciones fúngicas. En este artículo se revisan los conocimientos recientes sobre el papel de este antifúngico en el tratamiento de la mucormicosis y las infecciones fúngicas invasivas de brecha (IFIb) durante un tratamiento antifúngico. El isavuconazol ha demostrado resultados clínicos favorables y un buen perfil de seguridad en diversas poblaciones de pacientes con mucormicosis, incluidos aquellos con comorbilidades como diabetes mellitus o inmunosupresión grave. Cabe destacar especialmente el hecho de que en pacientes con mucormicosis en los que un trasplante de órgano sólido era un factor predisponente, las interacciones farmacológicas se han gestionado de forma eficaz. En el tratamiento de las IFIb, el uso de isavuconazol requiere una cuidadosa reflexión sobre las especies fúngicas implicadas y sus perfiles de sensibilidad. Esto depende en gran medida del agente antifúngico administrado antes de la aparición de la IFIb. El diagnóstico precoz y el tratamiento antifúngico adecuado son esenciales para mejorar los resultados en pacientes con mucormicosis e IFIb. El isavuconazol representa una opción valiosa para el tratamiento de estas infecciones complejas.

Isavuconazole, a triazole-class antifungal agent, received marketing authorization in the European Union in 2015. Various studies have documented its association with favorable clinical responses and a good safety profile, whether used as primary treatment or rescue therapy. The antigungal spectrum of this drug includes yeast-like fungi such as Candida or Cryptococcus, dimorphic fungi such as Histoplasma or Blastomyces, and hyaline molds such as Aspergillus or Mucor, among others. In this review, we analyze the role of isavuconazole in the treatment of mucormycosis and breakthrough invasive fungal infections under other antifungal therapies.

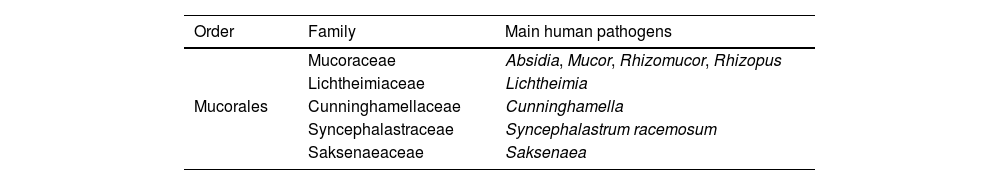

MucormycosisMucormycosis encompasses a group of severe fungal infections caused by fungi belonging to the order Mucorales. This order comprises 13 families, 56 genera, and over 300 species. Table 1 summarizes the most common Mucorales species involved in human pathology. Species of the genus Rhizopus are the predominant cause of mucormycosis globally, accounting for over 70% of all reported cases of the disease.17-19 In contrast, other species from different genera, such as Cunninghamella, Apophysomyces, Saksenaea, Rhizomucor, Cokeromyces, Actinomucor, and Syncephalastrum, account for less than 5% of reported cases of mucormycosis.6

The association between infections caused by Mucorales and uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, particularly when linked to diabetic ketoacidosis, has been well established for years. This relationship is attributed to various factors that create a favorable environment for the fungus, including immune system dysfunction in the context of hyperglycemia and acidosis, the enhanced growth conditions for Mucorales due to excess glucose and/or elevated free plasma iron levels in ketoacidotic states, and tissue necrosis that facilitates fungal angioinvasion. The classic clinical presentation of this disease is the rhinocerebral form.

Although there is no specific literature analyzing the role of isavuconazole in patients with mucormycosis associated with diabetes mellitus, real-world studies and isolated case reports are available,1,4,11 and the impact of this drug in populations with advanced age or comorbidities has been reported. These studies include a description of the prognosis of patients treated with isavuconazole, aged ≥65 years, with obesity (BMI ≥30), diabetes mellitus, renal insufficiency, or prolonged QT interval. The results show that patients with one or more of the aforementioned predisposing factors had similar outcomes compared to those without them in terms of response to primary antifungal therapy, adverse events, overall mortality, and mortality related to invasive fungal infections (IFI) at 6 and 12 weeks. Therefore, these data support the safety profile of isavuconazole in this population as well. In recent years, mucormycosis associated with diabetes mellitus has been diagnosed less frequently, despite the rapid increase in the prevalence of diabetes in the Western world.10 Several factors, such as better overall control of diabetes in patients or the widespread use of statins in this population, which have direct inhibitory activity against a variety of Mucor species, could explain this trend.

On the other hand, the number of immunocompromised patients with mucormycosis has increased exponentially in the last decade. Factors such as improved survival rates among onco-hematological patients, new immunosuppressive treatments, or advances in diagnostic techniques may explain this phenomenon. The clinical forms of mucormycosis vary depending on the location and the causative species, with the most common being rhinocerebral, pulmonary, and cutaneous.9 It is important to note that in most patients it is difficult to clinically differentiate mucormycosis from aspergillosis,2 and even bear in mind that whenever a patient has risk factors or suspicion of invasive aspergillosis, they may also have mucormycosis. Very recently, the results of using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for the diagnosis of mucormycosis have been described.12 This advancement is important because making a prompt diagnosis of mucormycosis with conventional methods is difficult, as the sensitivity of cultures is low and they are often not cost-effective, while microscopic visualization does not always allow precise identification of the causative fungus. PCR allows detecting DNA from several species of Mucorales (ranging from 4 to 11, depending on the type of PCR) in clinical samples. This technique is sensitive and specific. A recent study enabled the diagnosis of mucormycosis complicating severe COVID-19 in 7% of patients admitted to an ICU in France.7 Other studies have shown that up to 30% of patients may have a co-infection with Mucorales and Aspergillus.12 However, it is important to note that using PCR for the diagnosis of mucormycosis is not yet available in all laboratories. Furthermore, PCR is complementary and must be interpreted alongside clinical symptoms and other diagnostic tests.

It is important to highlight that some species of Mucorales may be less susceptible to isavuconazole, while others may have reduced susceptibility to posaconazole. Therefore, obtaining a positive culture and performing antifungal susceptibility testing is crucial in the clinical management of these infections.

The treatment of mucormycosis requires a multidisciplinary approach that combines the use of antifungals with aggressive surgical interventions to remove necrotic tissue when possible. Early identification and control of predisposing factors are essential for improving prognosis in these patients. Currently, we have several antifungals with activity against Mucorales: amphotericin B, posaconazole, and isavuconazole.

The first study evaluating the role of isavuconazole in mucormycosis was the VITAL study.20 In this study, the efficacy and safety of isavuconazole in patients with mucormycosis were explored through an open-label, single-arm design. A total of 37 patients with mucormycosis received a loading dose of 200mg every 8h within the first 48h, followed by a maintenance dose of 200mg every 24h. The results showed that 11% of patients achieved a partial response, 43% remained stable, 3% experienced disease progression, and 35% died. In 8% of the cases, the response could not be assessed.

Subsequently, an efficacy analysis through a case-control study was conducted. Matching considered three dichotomous variables: disease severity (defined by central nervous system involvement or dissemination), presence of hematological malignancy, and surgical treatment within the first seven days of antifungal therapy. Control information was obtained from the FungiScope registry, a global database on emerging fungal infections. In the analysis, 33 control patients were compared with 21 patients from the VITAL study. Most of the controls initially received amphotericin B (with a median duration of 18 days), followed by posaconazole. The overall mortality at 42 days was 33% in the isavuconazole group and 39% in the controls. It is important to note that this study did not compare the adverse effects related to each antifungal.

Recently, some real-life experiences using isavuconazole have been described, showing that this antifungal is frequently used in the treatment of invasive mucormycosis. In a European study14 with 218 patients suffering from IFI and receiving isavuconazole, 11 had mucormycosis. Although the specific results for mucormycosis patients are not detailed separately, this study provides additional evidence supporting the potential of isavuconazole. Whether as a first treatment or after the failure of other antifungal therapies, isavuconazole is associated with a favorable clinical response and an adequate safety profile in patients with various underlying conditions. A retrospective and observational study was conducted at several centers in Spain, including solid organ transplant (SOT) recipients who received isavuconazole as treatment for IFI at different university hospitals.5 A total of 238 cases of IFI were recorded, of which 10 were mucormycosis. The most frequent sites of infection were deep soft tissues and the lung. Additionally, one-fifth of the patients had disseminated disease. This study represents, to date, the largest uncontrolled multicenter cohort published on the use of isavuconazole in patients with invasive aspergillosis (IA) and mucormycosis in solid organ transplant recipients, and again shows that the drug is well-tolerated, with clinical response rates comparable to those observed in other high-risk populations. In most cases, managing pharmacological interactions with immunosuppressive agents related to transplantation was feasible, something of utmost importance in this population.

In another retrospective study15 conducted at a single center in the United States, the risk factors and outcomes of solid organ transplant recipients, hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients, and patients treated with chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy, all suffering mucormycosis, were evaluated. A total of 43 patients were included in the analysis, 34 of whom were solid organ transplant recipients (79%). Isavuconazole was the most commonly used azole in recipients under monotherapy. The all-cause mortality rate was 64%, with 18 (75%) of those deaths directly related to mucormycosis. The highest mortality was observed in cases of disseminated and intraabdominal disease (100%), followed by pulmonary disease (50%).

Finally, a retrospective, observational, multicenter study conducted across 12 university hospitals in Spain between January 2018 and January 2022, evaluated 238 non-neutropenic patients with IFI that received isavuconazole for more than 24h.13 Among these cases, eight patients had mucormycosis. In this subgroup, although the majority of the patients had a disseminated disease and an unfavorable baseline prognosis, 25% of them achieved complete resolution. Consistent with previous studies, the use of isavuconazole proved to be an optimal treatment for non-neutropenic patients, with very low toxicity and notable effectiveness compared to previous results observed in patients with similar characteristics.

Breakthrough invasive fungal infectionsIn recent years, breakthrough invasive fungal infections (bIFI) have increased, especially among patients with hematologic malignancies, due to the widespread use of antifungal treatments as prophylaxis, early therapy, and targeted therapy. These infections have differential challenges compared to IFIs in patients who have not previously received antifungals. The definition of bIFI may vary according to different authors; bIFI was defined in a recent consensus3 as any IFI occurring during exposure to an antifungal drug, including IFI caused by fungi that are outside the spectrum of activity of that drug. The period that defines bIFI depends on the pharmacokinetic properties of the antifungal used initially and extends at least until a subsequent dosing interval after the treatment is discontinued.

One of the greatest challenges in bIFI is understanding the epidemiology of the fungi that cause the infections, which will largely depend on the antifungal previously used. In a Spanish study16 that described 121 bIFI in hematological patients, it was documented that most infections were caused by non-Aspergillus fumigatus Aspergillus species, non-Candida albicansCandida species, Mucorales, and other uncommon fungi and yeasts. Fig. 1 summarizes the results of the epidemiology of bIFI according to the antifungal used before the onset of the infection.

Epidemiology of bIFI in relation to the antifungal used before the onset of the infection. IMI: invasive mould infection. Taken from Ref. 16. Copyright 2023 Elsevier Ltd.

An important issue is that the diagnosis of these infections can be difficult due to the lower sensitivity of conventional culture techniques, serological tests, and PCR-based assays in patients receiving antifungal therapy, which often delays the diagnosis and contributes to unfavorable clinical outcomes.8 Therefore, an aggressive diagnostic approach to these infections is essential, as identifying the causative fungus and its antifungal susceptibility is crucial to prescribe a treatment. While awaiting these results, it is recommended to start broad-spectrum antifungals different from those previously used at an early stage.

Currently, there is limited experience described regarding patients with bIFI treated with isavuconazole. In the previously mentioned Spanish study, a total of 22 patients with bIFI, representing 18% of the cohort, were treated with an antifungal regimen that included isavuconazole. The exact outcome of this population is not described, but it is noted that the treatment of bIFI with echinocandins was associated with a high number of inappropriate treatments and increased mortality. In the already mentioned American study on solid organ transplant patients,15 84% of patients with mucormycosis had a bIFI, mostly following prophylaxis with posaconazole, and were predominantly treated with isavuconazole. However, the results of this clinical decision are not detailed.

Our recommendation in the treatment of bIFI would be to change the antifungal by another of a different class and, in case the fungus recovered in subsequent cultures shows susceptibility, consider reintroducing an azole (orally), preferably different from the one previously used.

In general, the mortality for patients with bIFI described in the literature is very high, making it essential to improve the management of these infections.

ConclusionsWith the available data up to now, we can confirm that isavuconazole is an effective therapeutic alternative for the treatment of both mucormycosis and bIFI due to antifungals other than azoles. In those bIFI due to posaconazole use, it is recommended to opt for a different antifungal class, such as amphotericin B, and consider reintroducing isavuconazole by switching to oral treatment if the fungus recovered in culture is susceptible to that antifungal agent.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing processDuring the preparation of this article the authors used ChatGPT as an aide to language translation and to improve the readability. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the text as needed, and take full responsibility for the content of the article.

FundingThe publication of this article has been funded by Pfizer. Pfizer has neither taken part, nor intervened in the content of this article.

CG-V [ICI21/00103] has received research grants from the Ministry of Health and Consumption, Carlos III Health Institute. The ICI21/00103 project has been funded by the Carlos III Health Institute (ISCIII) and co-financed by the European Union. TFA has received a predoctoral scholarship funded by the Ministry of Health and Consumption, Carlos III Health Institute [RH RH042953]. This study has been co-financed by the Carlos III Health Institute, file number CM23/00277, in accordance with the “Resolución de la Dirección del Instituto de Salud Carlos III, O.A., M.P.” of December 13, 2023, granting the Río Hortega Contracts, and co-financed by the European Union. This work was co-financed by a research grant (SGR 01324 Q5856414G) from the AGAUR (Agency for the Management of University and Research Grants) of Catalonia.

Conflict of interestCG-V has received fees for conferences on behalf of Gilead Science, MSD, Pfizer, Jansen, Novartis, Basilea, Shionogi, AbbVie, Advanz Pharma, Mundipharma, and grants from Gilead Science, Pfizer, MSD, Mundipharma, and Pharmamar. AS has received fees for conferences and participation in advisory boards from Merck Sharp and Dohme, Pfizer, Shionogi, Novartis, Angelini, and Menarini, as well as financial support from Pfizer and Gilead Sciences. TFA has received funding from Gilead Science, Pfizer, and Pharmamar to cover registration and travel expenses to attend scientific conferences.