Isavuconazole, a next generation triazole, exhibits unique pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties that make it ideal for treating invasive fungal infections in critically ill and immunocompromised patients. This antifungal agent stands out for its broad spectrum of activity, which includes filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus and Mucorales, with an efficacy comparable to that of voriconazole and additional advantages against these pathogens. Its high oral bioavailability (close to 100%), prolonged half-life (>100h), and linear, predictable pharmacokinetic profile minimize the need for frequent dose adjustments and therapeutic monitoring. Its lipophilic structure facilitates penetration into key tissues, such as the central nervous system and pulmonary tissue, as validated by clinical studies showing survival rates exceeding 70% in patients with complicated invasive fungal infection. Its use is safe in populations with renal impairment, mild to moderate hepatic impairment, paediatrics, and obesity, although dose adjustment is recommended for severe hepatic impairment. Recent studies in critically ill patients undergoing extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or continuous renal replacement therapy have revealed moderate reductions in plasma concentration, without significant clinical impact. Adaptive dosing strategies have been proposed to optimize efficacy in these cases. Compared to other triazoles, isavuconazole demonstrates a robust safety profile, with lower incidences of hepatotoxicity and neurotoxicity. Its antifungal activity, favorable pharmacokinetics, and excellent safety profile underscore its role as a reference antifungal agent, particularly in challenging clinical scenarios.

El isavuconazol, un triazol de nueva generación, presenta propiedades farmacocinéticas y farmacodinámicas únicas que lo hacen ideal para tratar infecciones fúngicas invasivas en pacientes críticos e inmunodeprimidos. Este antifúngico destaca por su amplio espectro de actividad, que incluye hongos filamentosos como Aspergillus y Mucorales, con una eficacia comparable al voriconazol y ventajas adicionales frente a estos patógenos. Su elevada biodisponibilidad oral (cercana al 100%), su prolongada semivida (>100 horas) y su perfil farmacocinético lineal y predecible minimizan la necesidad de ajustes frecuentes de dosis y de monitorización terapéutica. Su estructura lipofílica facilita la penetración en tejidos clave, como el sistema nervioso central y el tejido pulmonar, como validan los estudios clínicos que muestran tasas de supervivencia superiores al 70% en pacientes con infección fúngica invasiva complicada. Su uso es seguro en poblaciones con insuficiencia renal, insuficiencia hepática de leve a moderada, en pediatría y en pacientes con obesidad, aunque se recomienda ajustar la dosis en caso de insuficiencia hepática grave. Estudios recientes en pacientes críticos sometidos a oxigenación con membrana extracorpórea o terapia continua de reemplazo renal han revelado reducciones moderadas de las concentraciones plasmáticas, sin repercusiones clínicas significativas. Se han propuesto estrategias de dosificación adaptadas para optimizar la eficacia en estos casos. En comparación con otros triazoles, el isavuconazol presenta un perfil de seguridad sólido, con menor incidencia de hepatotoxicidad y neurotoxicidad. Su actividad antifúngica, su farmacocinética favorable y su excelente perfil de seguridad subrayan su papel como antifúngico de referencia, sobre todo en escenarios clínicos difíciles.

Isavuconazole (C16H14F3N5O) (mw 349) is a triazole with a chemical structure similar to fluconazole or voriconazole. However, it exhibits some distinctive characteristics, both in its antifungal spectrum (activity against zygomycetes) and its pharmacological profile (high liposolubility and tissue concentration, lower metabolic interaction), making it an attractive option for treating fungal infections in critically ill and immunosuppressed patients, even under unfavorable clinical conditions (renal or hepatic failure, comorbidity, changes in body distribution volume), which are common in this patient profile. In this review, we analyze features related to its molecular structure and its impact on the current epidemiology of invasive fungal infections (IFI), its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, its use in complex clinical models, and pharmacological monitoring. Since there is a section in this monograph addressing drug interactions, only safety-related aspects will be added here.

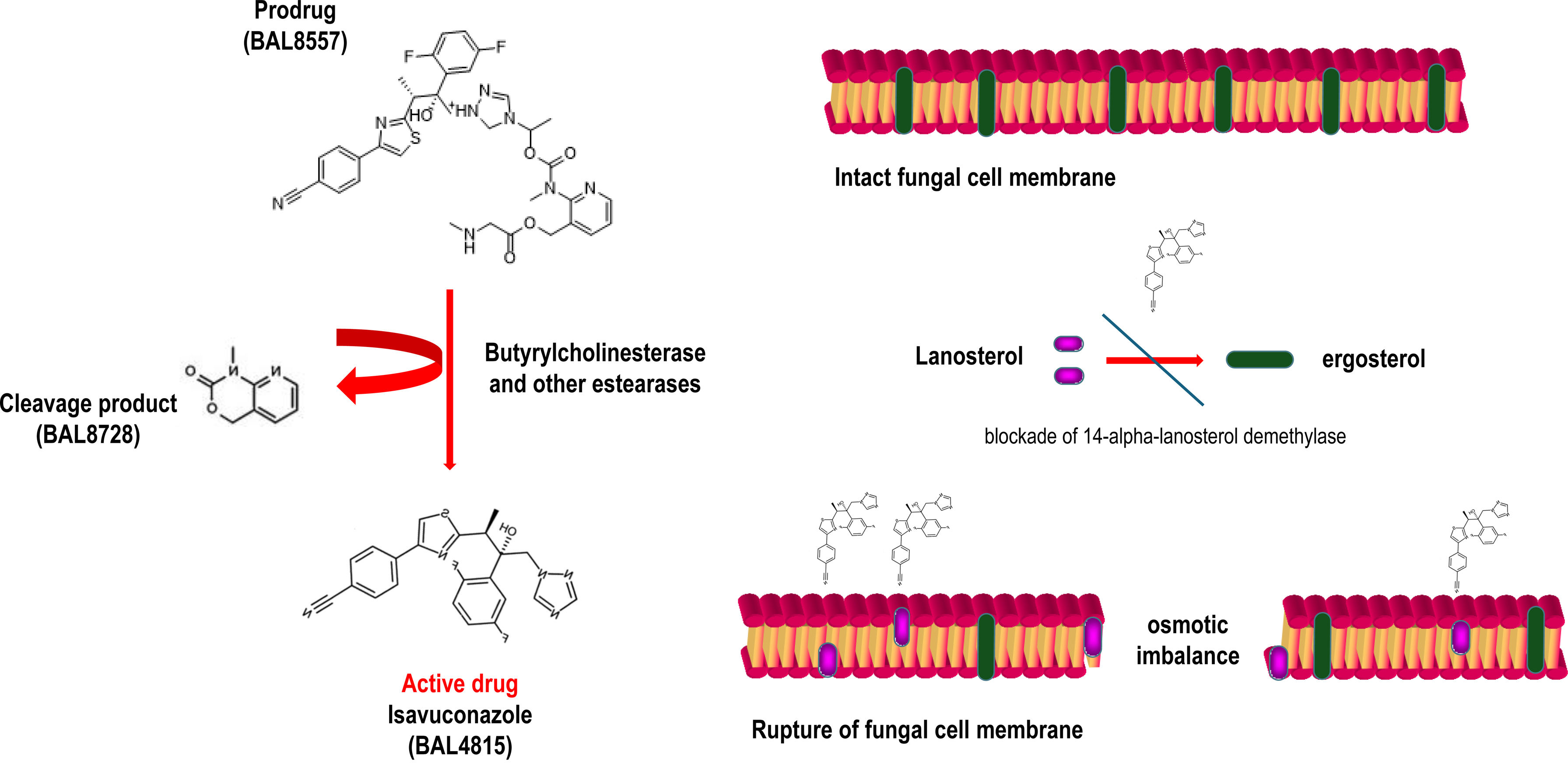

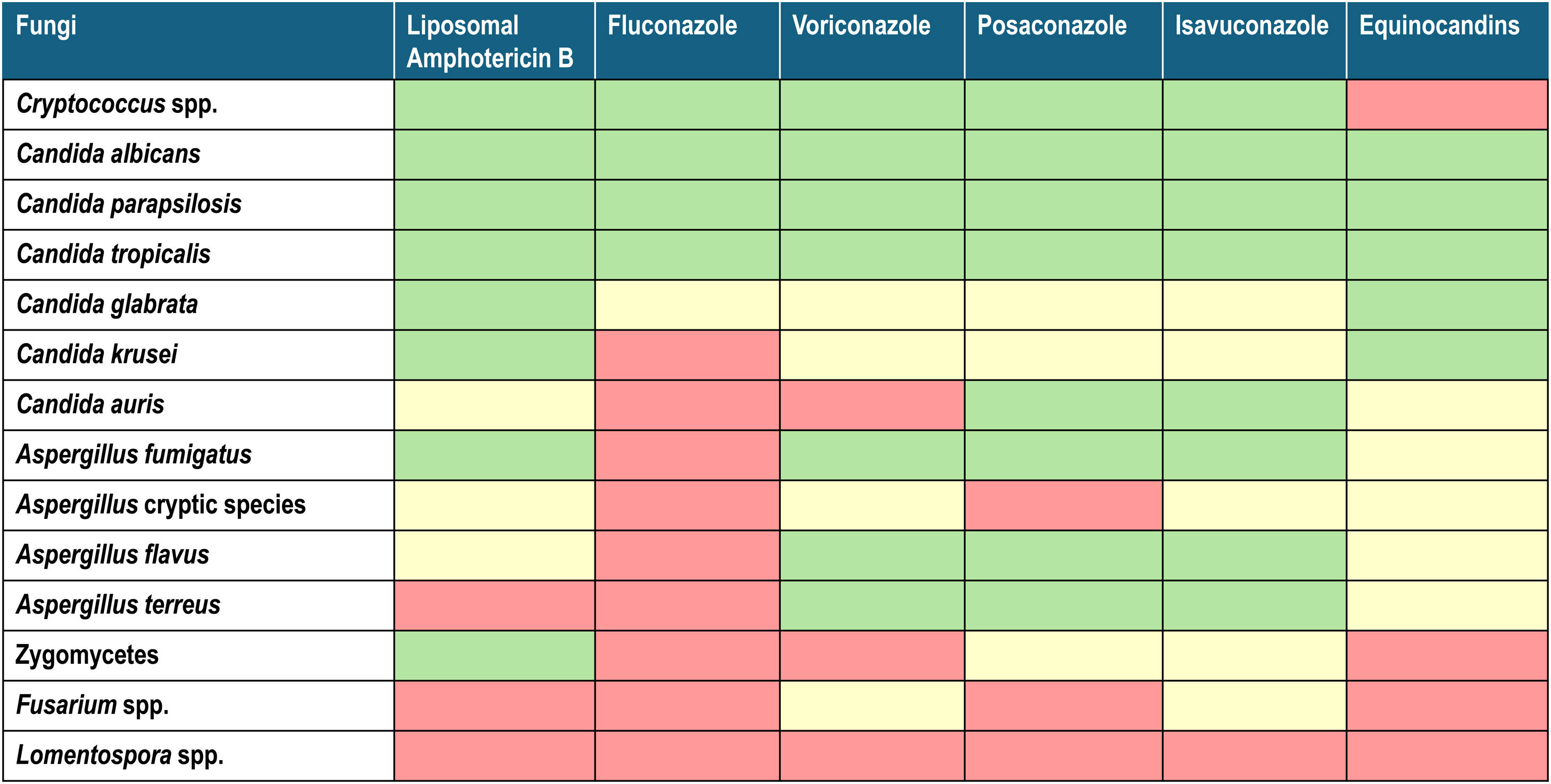

1The molecule, its spectrum, and its impact on the current epidemiology of fungal infectionsIsavuconazole is the active fraction of the prodrug isavuconazonium (BAL8557), with an aminocarboxyl group that increases its water solubility, eliminating the need for cyclodextrin to ensure plasma levels, as is the case of voriconazole. Once in plasma, through esterase action, mainly butyrylcholinesterase, the prodrug transforms into active isavuconazole. Its mechanism of action, similar to other triazoles, involves inhibiting the synthesis of ergosterol, a fundamental structural component of fungal membranes. This is achieved by blocking the enzyme 14-lanosterol demethylase (CYP51) of the cytochrome P450 family, encoded by the erg11 gene in Candida and the Cyp51A gene in Aspergillus.1,6 This results in cell wall instability, pore formation, and osmotic imbalance that lyses the fungal cell (Fig. 1). The antifungal spectrum of isavuconazole includes yeasts (with limitations for Candida glabrata and Candida guilliermondii), filamentous fungi of the Aspergillus genus, and Mucorales. However, it shows minimal activity against other genera such as Fusarium and Lomentospora (Table 1).

Two major epidemiological changes in recent years within Candida genus that could affect isavuconazole's activity are the emergence of Candida auris (worldwide) and the spread of azole-resistant Candida parapsilosis. As of August 2022, resistance patterns observed in azole-resistant C. parapsilosis isolates in the CANDIMAD study were as follows: voriconazole resistance (74.1%), posaconazole resistance (10%), and non-wild type resistance to isavuconazole (47.5%).39 Another recent study by the same authors analyzed the antifungal susceptibility of strains carrying mutations recovered from blood or peritoneal samples, observing that for the Y132F mutation the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of isavuconazole was ≤0.125mg/L for nearly all the strains analyzed, at least two dilutions lower than voriconazole. However, for the strains expressing a G458S mutation, the accumulated resistance was higher. The MIC of isavuconazole was ≤1mg/L, comparable to that of voriconazole. Posaconazole showed greater activity than voriconazole and isavuconazole against both mutation types, maintaining 100% of Y132F mutant strains with a MIC <0.06mg/L, and 0.25mg/L for G458S mutants.15 Increased resistance mediated by the FKS-1 gene in C. glabrata or the intrinsic resistance of Candida krusei to fluconazole has not recently altered therapeutic approaches with this drug.

Isavuconazole's antifungal activity against Aspergillus genus is similar to that of voriconazole.35,36,45 However, the key factor distinguishing isavuconazole over other marketed triazoles (itraconazole, voriconazole, posaconazole) is its activity against Mucorales. This feature encompasses its lipophilic properties that allow a better penetration into cellular membranes, its high affinity for binding to the catalytic site of the 14-α-lanosterol demethylase enzyme, and its high capacity to interfere with ergosterol biosynthesis in this group of fungi compared to other azoles like voriconazole. Besides, the increased permeability caused by a reduced ergosterol synthesis, the enzyme inhibition leads to the accumulation of toxic intermediates.44,46 Another review in this monograph addresses the changing epidemiology of IFI and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, discussing isavuconazole's microbiological activity.

2Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of isavuconazole2.1Dosage and steady-state achievementIsavuconazole is a triazole with both oral and intravenous availability. The recommended dosage is 200mg every 8h for two days, followed by 200mg daily (oral or intravenous). Its oral bioavailability is nearly 100%. In children, the dosage is 5.4mg/kg every 8h for two days, followed by 5.4mg/kg (maximum 200mg) daily. It is not dialyzable, so dosage adjustments are not required in renal failure or during plasma exchange techniques.

Without a loading dose, achieving steady state would take up to 14 days (its elimination half-life exceeds 100h). However, after administering a loading dose of 200mg three times a day for 48h, steady state is reached within 72h. At this dosage, and with normal interindividual variations of approximately 20%,12 plasma trough concentrations (Cmin) of around 3mg/L are achieved, which is above the MIC of approximately 1–2mg/L, the sensitivity cutoff recommended by EUCAST for Aspergillus species.

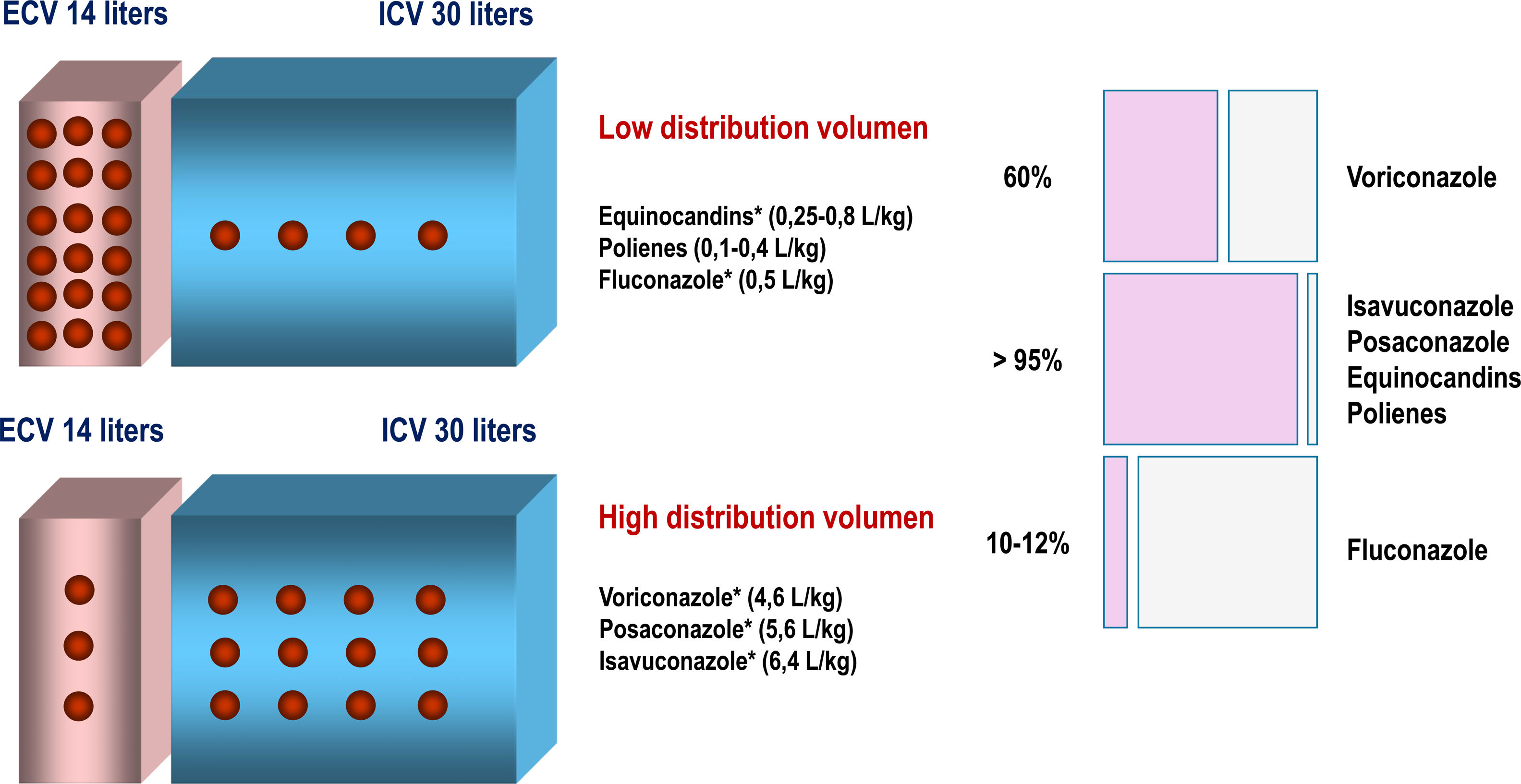

2.2Distribution and clinical impactIts volume of distribution, like that of posaconazole or voriconazole, is high, specifically about 304–494L. Its protein binding exceeds 99%, and its bioavailability is 98%6,34,48 (Fig. 2). The volume of distribution expressed in L/kg is used to predict plasma concentrations after administering a given dose, but provides little information about the specific distribution pattern of the drug.

A recent study in healthy volunteers demonstrated average concentrations measured in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) after lumbar puncture, epithelial lining fluid (ELF) following bronchoscopy, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) after venipuncture of 0.07±0.03, 0.94±0.46, and 27.1±17.8mg/L, respectively.7 Although isavuconazole's concentration in CSF in this study might appear modest, higher concentrations have been observed in brain tissue rather than in CSF.34 A clinical study on fungal infections in the central nervous system (CNS) – Aspergillus, Mucorales, Cryptococcus – involving 27 patients with hematologic malignancies participating in the phase III VITAL or SECURE trials demonstrated an overall survival rate of 80.6% on day 42 and 69.4% on day 84, with a complete or partial clinical response achieved in 58.3% of patients at the end of the treatment.49 Another retrospective multicenter study with 131 patients used isavuconazole in salvage therapy, 15 of whom had CNS infections, achieving a response rate of 73%.22

Recent evidence on isavuconazole's pulmonary diffusion is critical for managing IFIs. A recent study analyzed its pharmacokinetics in lung transplant recipients to evaluate its bronchopulmonary penetration. This study included 13 patients and showed mean serum concentrations of 3.30mg/L (SD 0.45mg/L), 5.12mg/L (SD 1.36), and 6.31mg/L (SD 0.95) at 2h, 4h, and 24h, respectively. Mean ELF concentrations were 0.969mg/L (SD 0.895), 2.141mg/L (SD 1.265), and 2.812mg/L (SD 0.693) at the same time points, suggesting its potential utility in treating invasive pulmonary mycoses.10

Using the dosing regimen employed in clinical trials, total drug AUC/MIC values of 50.5 for Aspergillus species (MIC value up to 0.5 mg/L, CLSI standards), between 270 and 5053 for Candida albicans (with MIC values up to 0.125 and 0.004mg/L, respectively), and 312 for non-C. albicans Candida species (MICs up to 0.125mg/L) were achieved.31

2.3EliminationIsavuconazole has an elimination half-life of 100–115h. Its primary metabolic pathway involves the oxidation of the cyano group, carbomoyl oxidation, and triazole ring cleavage. These products are glucuronidated and conjugated with N-acetylcysteine. Metabolic products are excreted equally via faeces and urine (45% each), with less than 1% of intact free isavuconazole eliminated in urine.6

3Clinical experience in special situationsVarious studies have focused on analyzing the pharmacokinetics of isavuconazole in special situations such as renal or hepatic insufficiency, obesity, and pediatric populations. In renal insufficiency, a phase 1 study showed no differences in drug serum concentrations between subjects with normal renal function and those with mild to severe renal insufficiency, including patients undergoing hemodialysis. Therefore, dose adjustments were deemed unnecessary.51

A pharmacokinetic population model developed for subjects with hepatic insufficiency observed that individuals with mild to moderate hepatic insufficiency had less than a twofold increase in minimum isavuconazole concentrations compared to healthy subjects, concluding that dose adjustments are unnecessary for these individuals.13 However, in cases of severe hepatic insufficiency, another analysis showed a 60% reduction in drug clearance, prompting a recommendation to reduce the dose by 50% in such patients.27

Regarding obese patients, the SECURE clinical trial evaluated 263 patients with proven or probable fungal infections, including 25 with a BMI >30kg/m2. These patients received standard doses of isavuconazole and exhibited similar clinical efficacy and adverse effect rates as those with lower BMI.20 Although the experience correlating drug distribution and clinical efficacy in this population is insufficient, current recommendations support standard dosing.11

In phase 1 and 2 clinical trials of isavuconazole in pediatric patients, a dosage of 5.4mg/kg was well tolerated and met the predefined exposure threshold above the 25th percentile for the concentration-time area under the curve, similar to adults (≥60mgh/L).3,50 Additionally, phase 2 efficacy and safety results were comparable to those in adults. More recently, real-world studies analyzing outcomes in paediatric populations have corroborated the efficacy and safety inferred from clinical trials data (Table 2).

Clinical experience in determining isavuconazole concentration.

| No. of patients (measurements) | Type of patient | Median concentration and ranges | % of measurements in therapeutic range (therapeutic window ≥1mg/L) | % variation | Factors analyzed that conditioned the variation according to the authors | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 (81 measurements) | Pediatrics, some of them in ICU | 3.1mg/L (2.4–4.5mg/L) | 100% over 1mg/L(69.4% over ≥2.5mg/L) | 50 | Pediatric patients, ECMO | 16 |

| 16 | Pediatrics | 2.9mg/L (1.93.5 mg/L) | 91.6% | 74 | – | 18 |

| 15 | Pediatrics (9 under treatment, 6 under prophylaxis) | 3.19mg/L (0.88; 5.00) under treatment2.94mg/L (2.77; 3.29) under prophylaxis | NA | 20 | Pediatric patients | 54 |

| NA (283 measurements vs 2458 from 551 patients in three clinical trials) | Adults | Median, mean and SD were 2.98, 2.6 and 1.91mg/L | 90% | 66 | – | 2 |

| 35 (283 measurements) | Adults | 2.92mg/L (1.82–5.33mg/L) | 89% (71% >2) | NA | – | 21 |

| 45 (285 measurements) | Adults | 4.1mg/L (1.1–10.1mg/L).(SD) 4.6±1.4mg/L for patients taking 200mg daily, 4.16±1.5mg/L for patients taking 200mg/100mg every other day, and 3.76±1.4mg/L for patients taking 100mg daily | 100% | NA | – | 30 |

| 33 (304 measurements) | Adults | 2.8mg/L (2.0–3.7mg/L) | 78% (study with a therapeutic window in ≥2mg/L) | 30.7–41.5% | ASAT concentration (U/L) and albumin concentration (g/L) | 9 |

| 35 (273 measurements) | Adults | 4.3mg/L (0.5–15.4mg/L) | 83% (study with a therapeutic window of 2–5mg/L) | 54.8% | NA | 47 |

| 32 (145 measurements in 29 courses analyzed) | Adults, mixed cohort with ECMO and CRRT | 2.35mg/L (0.66–9.1mg/L); 3.05mg/L (1.38–9.1mg/L) without ECMO and CRRT | NA | NA | ECMO, CRRT | 55 |

| 41 (223 measurements) | ICU adults | The overall median Cmax was 2.36mg/L (mean 2.43mg/L, [0.41–7.79])The overall median Cmin was 1.74mg/L (mean 1.77mg/L, [0.24–4.96]) | 69% | NA | BMI >25, SOFA >12CRRT, septic shock did not influence isavuconazole concentration | 26 |

| 72 | 33 ICU adults, 39 non-ICU adults | 3.33±2.26mg/LOutside ICU 4.15±2.31mg/LInside ICU 2.02±1.22mg/L (p value 0.001) | Non-ICU 97.3%ICU 80.5% | NA | ICU, BMI >25, bilirrubin >1.2mg/dL | 40 |

| 62 | ICU adults | 1.64mg/L (0.83–2.24mg/L) | 65.6% | NA | Age ≤Sex female, BMI >25, SOFA >12, CRRT, ECMO | 8 |

| 7 (64 measurements) | ICU adults under ECMO | Median Cmin 0.24 (0.22–0.50mg/L)Median Cmax 1.3 (1.10–1.72mg/L) | NA | NA | ECMO did not influence isavuconazole concentration | 32 |

| 15 | ICU adults under ECMO | Cmin=1.02mg/L (0.89–1.07mg/L) after first loading dose 400mg; 2.38mg/L (2.10–2.78mg/L) at steady state | 100% at different doses (200, 300, 400mg) | NA | NA | 25 |

| 2 | ICU adults under ECMO | 1.5mg/L (1–2mg/L) | – | – | ICU | 38 |

| 24 | ICU adults, some of them under ECMO | 1.76mg/L (±1.02mg/L) | 87.5% | NA | None of studied factors (BMI >25, SOFA >12, CRRT, ECMO) had influence in concentration | 37 |

ASAT: aspartate amino transferase; ECMO: extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; CRRT: continuous renal replacement therapy; BMI: body mass index; SOFA: sequential organ failure assessment; ICU: intensive care unit; NA: not available.

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is becoming increasingly important in antimicrobial therapy. TDM is clinically indicated for drugs with a narrow therapeutic margin or nonlinear pharmacokinetics that complicate predictability. Linearity condition is assessed by the correlation between higher plasma concentrations (when increasing the dose) or lower concentrations (when decreasing the dose) once the steady state is reached. Isavuconazole steady state with the conventional dose is achieved in 14 days without a loading dose, and in 72h with a loading dose. Therefore, the drug is linear and predictable when administered at the conventional dose and after a loading dose in both adult and pediatric population.3,50

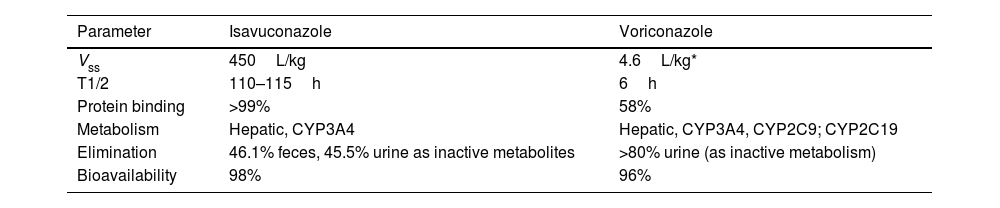

As previously discussed, isavuconazole exhibits linear, stable, and predictable pharmacokinetics, contrasting with voriconazole, which has nonlinear pharmacokinetics due to saturable metabolism19 and susceptibility to CYP2C19 genetic polymorphisms.33 Furthermore, isavuconazole's prolonged elimination half-life (>100h compared to 6h for voriconazole) (Table 3) further enhances its stability. This stability is reflected in lower inter- and intra-patient variability, as observed in the SECURE clinical trial and real-world studies, where plasma concentrations follow a more consistent normal distribution than voriconazole.2,47

PK parameters of isavuconazole and voriconazole (SmPC AEMPS 2024).

| Parameter | Isavuconazole | Voriconazole |

|---|---|---|

| Vss | 450L/kg | 4.6L/kg* |

| T1/2 | 110–115h | 6h |

| Protein binding | >99% | 58% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic, CYP3A4 | Hepatic, CYP3A4, CYP2C9; CYP2C19 |

| Elimination | 46.1% feces, 45.5% urine as inactive metabolites | >80% urine (as inactive metabolism) |

| Bioavailability | 98% | 96% |

Vss: volume of distribution at steady state; T1/2: half-life.

From a clinical efficacy perspective, the therapeutic range for isavuconazole is not well defined as no significant correlation between drug exposure and clinical outcomes has been identified.14 EUCAST sets the isavuconazole breakpoint for Aspergillus fumigatus at 1mg/L.5 Although serum Cmin is not a surrogate for the AUC/MIC ratio, it could serve as a pharmacological target. Real-world studies indicate that most patients achieve Cmin levels above 1mg/L (Table 2).

Defining the therapeutic range also requires understanding toxicity at high serum concentrations of antifungals. For voriconazole, elevated serum concentrations correlate with hepatic and neurological toxicity, often leading to drug discontinuation.43,52 In contrast, for isavuconazole, no such relationship between high serum levels and hepatic toxicity has been established.14 However, a study involving 19 patients found gastrointestinal adverse effects such as anorexia and reduced appetite at concentrations exceeding 5.13mg/L, particularly with prolonged treatment (median of 134 days).17 Consequently, 5mg/L has been suggested as the toxicity threshold for isavuconazole (Table 2). Nonetheless, subsequent studies have not consistently correlated serum concentration with toxicity.

In critically ill patients, physiological changes related to infection severity or critical care therapies (e.g., increased distribution volume, altered hepatic/renal clearance, or hypoalbuminemia) are expected.41 Studies investigating serum isavuconazole concentration in critically ill patients found that Cmin concentration is generally lower than that in non-critical patients (Table 2), but remain above 1mg/L in most cases.2,8,9,16,18,21,25,26,28,30,32,37,38,40,47,54,55 Factors significantly associated with reduced isavuconazole concentration include BMI >25, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), continuous renal replacement therapy (CRRT), SOFA scores >12, female sex, bilirubin >1.2mg/dL, and advanced age. These factors vary across studies due to methodological differences and population-specific biases (Table 2). Among these variables, increased BMI in critically ill patients consistently affects serum isavuconazole concentration, showing an inverse linear relationship in three of four analyzed studies.40 For ECMO, hydrophobic drugs like isavuconazole may adhere to the oxygenator membrane. However, one study found that pre- and post-oxygenator serum concentrations were similar to those at steady state, suggesting minimal impact from membrane adsorption.32 This observation may result from membrane saturation at steady state, preventing further drug loss. Nonetheless, other studies involving ECMO patients reported reduced isavuconazole serum concentrations post-procedure.8,25,55 In patients undergoing CRRT, high protein binding typically suggests lower drug loss during dialysis. However, real-world findings are contradictory: some studies report significantly lower isavuconazole serum concentrations in CRRT patients,8,55 while others do not.26,37 The extracorporeal circuit's increased distribution volume may explain these discrepancies.

In critically ill patients, increased distribution volume due to high BMI or extracorporeal circulation could significantly impact isavuconazole concentration. Some authors recommend TDM and more aggressive dosing strategies, leveraging the drug's favourable safety profile. For ECMO, a study proposed doubling the initial loading dose (200–400mg/L) to achieve levels >1mg/L within 2h without compromising tolerability.8 Other pharmacokinetic studies suggest adaptive dosing based on 24-h measurements, increasing maintenance doses to 400mg if concentration is <1mg/L, or to 300mg if concentration is 1–1.5mg/L.28 While adaptive dosing strategies may be practical, their clinical impact on patient outcomes compared to standard therapy remains unproven.

Given the above, unlike voriconazole, routine TDM for isavuconazole appears unnecessary. This conclusion aligns with recommendations from various international therapeutic guidelines (Table 4).4,23,24,42 However, in clinical scenarios where PK/PD parameters might be altered, such as in critically ill patients, or patients on ECMO or CRRT, monitoring the antifungal concentration could be warranted.

Timing and target trough concentration for TDM when administering azole antifungal agents.

| Antifungal | Objective | Timing | Target trough concentration (mg/L)Country/region (ref.) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan23 | Europe4 | USA42 | |||

| Voriconazole | Prophylaxis | 5–7 days after starting therapy | 1–4 (HPLC recommended) | 1–6 (HPLC) | 1–5.5 (HPLC) |

| Treatment | 2–5 days after starting therapy | ||||

| Posaconazole | Prophylaxis | 7 days after starting therapy | No recommendation | >0.7 | 0.5–0.7 |

| Treatment | 7 days after starting therapy | No recommendation | >1.0 | ≥0.5 | |

| Isavuconazole | Treatment | No recommendation | No recommendation | No recommendation | No recommendation |

Isavuconazole, a next generation triazole available in oral and intravenous formulations, stands out for its stable and predictable linear pharmacokinetics. Its near-100% oral bioavailability and prolonged half-life (>100h) allow rapid attainment of effective plasma concentrations following an initial loading dose. This predictability makes it standing out from other antifungals, like voriconazole, which exhibits nonlinear pharmacokinetics dependent on genetic polymorphisms. Routine therapeutic drug monitoring is unnecessary, simplifying its clinical management.

Its extensive distribution volume and >99% protein binding ensures effective tissue concentrations in invasive infections, including those in the CNS and lung tissue. Studies in critically ill populations on ECMO or plasma exchange suggest these interventions may reduce plasma levels, though no clear correlation with clinical efficacy has been established. Isavuconazole is also safe in patients with mild/moderate renal or hepatic insufficiency and paediatric patients, requiring dose adjustments only in cases of severe hepatic impairment. Its excellent tolerability and proven activity in clinical trials against invasive infections highlight its clinical utility.

FundingThe publication of this article has been funded by Pfizer. Pfizer has neither taken part, nor intervened in the content of this article.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

The authors express their gratitude to Manuel Gálvez for his collaboration in compiling and verifying the clinical documentation necessary for this article. His support and dedication were instrumental in completing this work.