Biological control of gastrointestinal nematodes of ruminants by use of nematophagous fungi would become part of any livestock parasite integral control system. Identifying autochthonous species that could then be selected for mass production is an important phase in the practical use of biological control.

AimsTo search for nematophagous fungi with potential use as biological control agents against gastrointestinal nematodes in Argentina.

MethodsDecomposing cattle faeces sampled in different locations were incubated in water agar 2% with Panagrellus sp. The developed nematophagous fungi were transferred to new water agar 2% plates and then to corn meal agar plates in order to carry out their identification. Fungal diversity and richness were also assessed.

ResultsSeventeen species from nine genera of nematophagous fungi were found. Twelve species were nematode-trapping fungi and three species plus two fungi identified to genus level corresponded to endoparasitic fungi. Arthrobotrys conoides, Arthrobotrys oligospora, Duddingtonia flagrans, Monacrosporium doedycoides, Arthrobotrys robusta and Drechmeria coniospora were the most frequently isolated species overall in the whole study (6.6%, 5.7%, 5.7%, 5.7%, 4.7% and 4.7%, respectively) although other species were more frequently recorded at local levels such as Arthrobotrys pyriformis (18.8%). Only A. conoides has been previously isolated from ruminant faecal samples in Argentina. Five nematode-trapping fungal species are mentioned for the first time in the Americas

ConclusionsD. flagrans and A. conoides, both identified in the present study, are among the most promising ones as biological control agents against gastrointestinal nematodes of ruminants.

El control biológico de los nematodos gastrointestinales de los rumiantes mediante hongos nematófagos es una herramienta a considerar en los sistemas integrados de control parasitario del ganado. La identificación de las especies autóctonas de estos hongos que puedan ser seleccionadas para producción masiva es de gran importancia en el uso práctico del control biológico.

ObjetivosLlevar a cabo una búsqueda de hongos nematófagos de uso potencial como agentes de control biológico contra nematodos gastrointestinales en Argentina.

MétodosSe trabajó con muestras de heces bovinas en descomposición obtenidas en diferentes lugares. Las heces se incubaron en agar agua 2% con Panagrellus sp. Los hongos nematófagos desarrollados se transfirieron a nuevas placas con agar agua 2% y luego a placas con agar harina de maíz para su identificación. También se estableció la diversidad y riqueza fúngicas.

ResultadosSe aislaron diecisiete especies de hongos nematófagos, comprendidas en nueve géneros. Doce resultaron ser hongos depredadores, mientras que otras tres especies y dos hongos identificados hasta género eran hongos endoparásitos. Arthrobotrys conoides, Arthrobotrys oligospora, Duddingtonia flagrans, Monacrosporium doedycoides, Arthrobotrys robusta y Drechmeria coniospora fueron las especies más aisladas más en todo el estudio (6.6%, 5.7%, 5.7%, 5.7%, 4.7% y 4.7%, respectivamente), aunque otras especies aparecieron más frecuentemente de manera local, como Arthrobotrys pyriformis (18.8%). Solamente Arthrobotrys conoides se había aislado previamente en Argentina a partir de heces bovinas. Cinco especies depredadoras se mencionan por primera vez en toda América.

ConclusionesD. flagrans y A. conoides, dos de las especies aisladas en el presente estudio, se encuentran entre las más prometedoras como agentes de control biológico de nematodos gastrointestinales de rumiantes.

Gastrointestinal parasitosis in livestock is a serious health problem in a variety of production systems. Resistance to conventional anthelmintics,2,5,13,47 the enforcement of strict limits for drug residues in food, and the environmental impact of the widespread use of antiparasitic drugs14,15,17,21,22,49 emphasise the need for implementing alternative tools in the fight against parasitosis. Biological control of gastrointestinal parasites is a promising alternative to tackle this problem. It is based upon the idea of exploiting parasites’ natural enemies to interfere with their natural cycles.27

Biological control by use of nematophagous fungi is considered to be part of parasite integral control systems. Among these fungi, Duddingtonia flagrans is one of the most promising species.27 Cosmopolitan nematophagous fungi colonise soils rich in organic matter under different temperature and humidity conditions, thus contributing to the biological equilibrium of the soil by interacting with local microflora and microfauna. They are usually isolated from soil and faeces from different animals.

A number of studies have been performed in different world eco-regions to identify nematophagous fungi. The search for nematophagous fungi with potential use in biological control in agriculture and livestock production in the Americas includes, among others, Mahoney & Strongman30 in Canada, Lappe and Ulloa26 and Acevedo-Ramírez et al.1 in Mexico, Búcaro4 in El Salvador, Orozco,35 Soto-Barrientos et al.45 and Peraza-Padilla et al.36 in Costa Rica, Persmack et al.37 in Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Panama, Rubner39 in Ecuador, and Saumell41 and Saumell et al.42 in Brazil. Gamundí and Spinedi18 is the only study to date describing the presence of nematophagous fungi such as nematode-trapping and endoparasitic ones (note: egg- and cyst-parasitic fungi and toxin-producing fungi are not the focus of the present study).

The aim of this study was to search for nematophagous fungi with potential use as biological control agents against gastrointestinal nematodes in Argentina, and classify them taxonomically. The search for these fungi in cattle faeces from the main livestock regions in Argentina will contribute to identify autochthonous species naturally colonising bovine faeces. The most efficient of those species, provided that they resist laboratory manipulation, could then be selected for mass production and formulation for practical use in livestock.

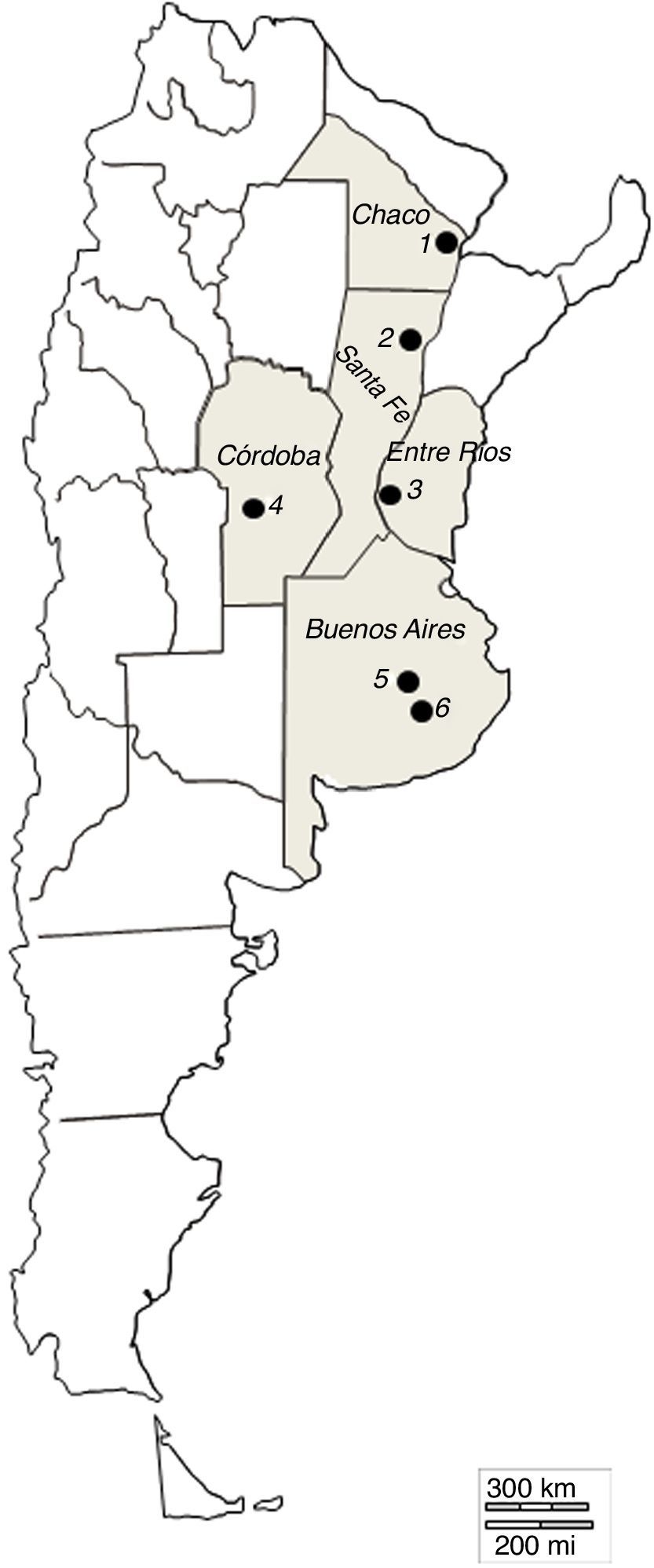

Materials and methodsSampling and isolation of fungiSamples of decomposing cattle faeces naturally voided were collected from September to November in two consecutive years. The collection sites were commercial cattle farms close to the following cities: Tandil (37°19′18″S, 59°04′50″W) and Azul (36°49′01″S, 59°50′05″W) in Buenos Aires province; Reconquista (29°09′41″S, 59°42″21′O) in Santa Fe province; Río Cuarto (29°45’44″S, 63°27’29”W) in Córdoba province; Resistencia (27°27′5″S, 58°59′12″W) in Chaco province; and Victoria (30°59′6″S, 57°55′12″W) in Entre Ríos province (Fig. 1). Samples from Tandil included as well those collected at the University Campus of the Faculty of Veterinary Sciences, National University of Central Buenos Aires Province. Subsamples of approximately 2g were incubated at room temperature (20–24°C) in Petri dishes containing water agar 2% that had been previously inoculated with Panagrellus sp. to promote fungal growth. The plates were regularly checked for three weeks under optical microscope with magnification capacity up to 100×, after which the nematophagous fungi that had developed were transferred to similar plates (water agar 2% plus Panagrellus sp.). Once the presence of fungal conidia or zoospores – depending on the fungi – had been detected in the second plates, the fungi were transferred to Petri dishes containing corn meal agar (Difco®). In the case of Myzocytium sp. and Stylopage grandis, the transferred structures were nematodes infected with zoospores.

Map of Argentina showing the sampling sites where decomposing cattle faeces were collected. Each black circle represents one sampling site: 1: Resistencia (27°27′5″S, 58°59′12″W), Chaco province; 2: Reconquista (29°09′41″S, 59°42′21″O), Santa Fé province; 3: Victoria (30°59′6″S, 57°55′12″W), Entre Ríos province; 4: Río Cuarto (29°45’44″S, 63°27’29”W), Córdoba province; 5: Azul (36°49′01″S, 59°50′05″W) and 6: Tandil (37°19′18″S, 59°04′50″W), Buenos Aires province.

Each isolate from either sterile or inoculated plates was identified under lightfield microscope using the keys by Subramanian,46 Cooke and Godfrey,7 Cooke and Dickinson,6 Haard,19 Schenk et al.,43 van Oorschot,48 de Hoog and van Oorschot,8 Liu and Zhang,28 Rubner,40 and Scholler et al.,44 and on the basis of the original descriptions; lactophenol cotton blue stain was applied as needed. When needed, scientific names were updated according to the latest nomenclatural changes.23 The most promising fungal isolates were kept on sterile water agar plates refrigerated at 4°C in the Laboratory of Parasitology, FCV, UNICEN, Tandil.

The diversity of nematophagous fungi was assessed based on the Simpson (D′) and Shannon (H′) diversity indices29 and the species richness index (S′), using the PAST v.3 software.20

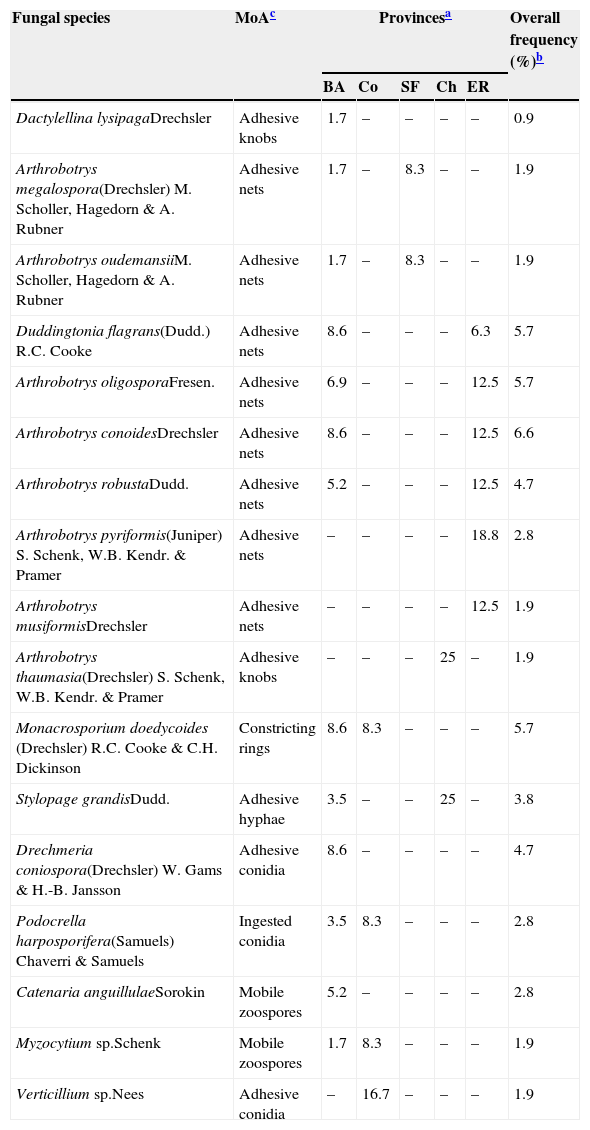

Results and discussionSeventeen species from nine genera of nematophagous fungi were found colonising decomposing cattle manure in the sites sampled. Twelve species belonged to nematode-trapping fungi, with adhesive nets being the mechanism of action most commonly observed. Monacrosporium doedycoides, Arthrobotrys conoides, Arthrobotrys oligospora, Arthrobotrys robusta, D. flagrans and Drechmeria coniospora were the most frequently isolated species, although frequencies of occurrence at provincial level show a different picture for several fungal species (Table 1). For example, Arthrobotrys pyriformis was by far the most frequent species (18.8%) in Entre Ríos but its overall frequency in the study (2.8%) masks the relative importance this species might have at local level. Equally, no single species was found in more than two provinces (Table 1). Two out of the five endoparasitic fungi found were identified only to genus level, i.e. Verticillium sp. and Myzocytium sp.

Frequency of occurrence (%) of nematophagous fungi in decomposing cattle faeces in five provinces and in the study as a whole.

| Fungal species | MoAc | Provincesa | Overall frequency (%)b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BA | Co | SF | Ch | ER | |||

| Dactylellina lysipagaDrechsler | Adhesive knobs | 1.7 | – | – | – | – | 0.9 |

| Arthrobotrys megalospora(Drechsler) M. Scholler, Hagedorn & A. Rubner | Adhesive nets | 1.7 | – | 8.3 | – | – | 1.9 |

| Arthrobotrys oudemansiiM. Scholler, Hagedorn & A. Rubner | Adhesive nets | 1.7 | – | 8.3 | – | – | 1.9 |

| Duddingtonia flagrans(Dudd.) R.C. Cooke | Adhesive nets | 8.6 | – | – | – | 6.3 | 5.7 |

| Arthrobotrys oligosporaFresen. | Adhesive nets | 6.9 | – | – | – | 12.5 | 5.7 |

| Arthrobotrys conoidesDrechsler | Adhesive nets | 8.6 | – | – | – | 12.5 | 6.6 |

| Arthrobotrys robustaDudd. | Adhesive nets | 5.2 | – | – | – | 12.5 | 4.7 |

| Arthrobotrys pyriformis(Juniper) S. Schenk, W.B. Kendr. & Pramer | Adhesive nets | – | – | – | – | 18.8 | 2.8 |

| Arthrobotrys musiformisDrechsler | Adhesive nets | – | – | – | – | 12.5 | 1.9 |

| Arthrobotrys thaumasia(Drechsler) S. Schenk, W.B. Kendr. & Pramer | Adhesive knobs | – | – | – | 25 | – | 1.9 |

| Monacrosporium doedycoides (Drechsler) R.C. Cooke & C.H. Dickinson | Constricting rings | 8.6 | 8.3 | – | – | – | 5.7 |

| Stylopage grandisDudd. | Adhesive hyphae | 3.5 | – | – | 25 | – | 3.8 |

| Drechmeria coniospora(Drechsler) W. Gams & H.-B. Jansson | Adhesive conidia | 8.6 | – | – | – | – | 4.7 |

| Podocrella harposporifera(Samuels) Chaverri & Samuels | Ingested conidia | 3.5 | 8.3 | – | – | – | 2.8 |

| Catenaria anguillulaeSorokin | Mobile zoospores | 5.2 | – | – | – | – | 2.8 |

| Myzocytium sp.Schenk | Mobile zoospores | 1.7 | 8.3 | – | – | – | 1.9 |

| Verticillium sp.Nees | Adhesive conidia | – | 16.7 | – | – | – | 1.9 |

BA: Buenos Aires; Co: Córdoba; SF: Santa Fé; Ch: Chaco; ER: Entre Ríos.

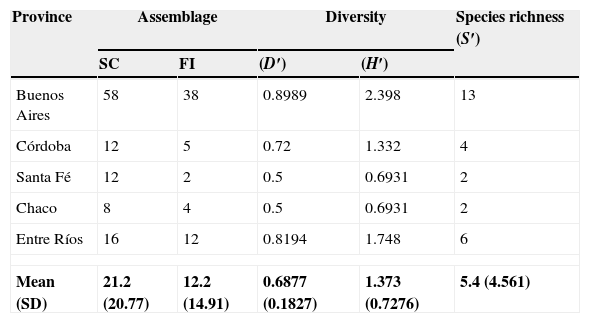

Species richness was highest in Buenos Aires province and lowest in Santa Fe and Chaco provinces (Table 2); however, the number of samples was much lower in one of the latter, i.e. Chaco, than in the former. Future studies should consider improved, balanced sampling schemes that would allow valid inferences in terms of climate and soil conditions favouring particular species of nematophagous fungi.

Assemblage, diversity and species richness of nematophagous fungi in decomposing cattle faeces in five provinces of Argentina.

| Province | Assemblage | Diversity | Species richness (S′) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SC | FI | (D′) | (H′) | ||

| Buenos Aires | 58 | 38 | 0.8989 | 2.398 | 13 |

| Córdoba | 12 | 5 | 0.72 | 1.332 | 4 |

| Santa Fé | 12 | 2 | 0.5 | 0.6931 | 2 |

| Chaco | 8 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.6931 | 2 |

| Entre Ríos | 16 | 12 | 0.8194 | 1.748 | 6 |

| Mean (SD) | 21.2 (20.77) | 12.2 (14.91) | 0.6877 (0.1827) | 1.373 (0.7276) | 5.4 (4.561) |

SC: Number of samples collected; FI: Number of fungal isolations; (D’): Simpson index; (H’): Shannon index; (S’): species richness index.

To the knowledge of the authors, five of the nematode-trapping fungal species isolated in the present study have not been described previously anywhere in the Americas, i.e. Dactylellina lysipaga, Arthrobotrys megalospora, Arthrobotrys oudemansii, M. doedycoides, Arthrobotrys thaumasia, D. flagrans, A. robusta, and A. pyriformis.

Among the species isolated in the present study, only A. conoides has been previously described in sheep faecal samples in Argentina,18 along with Arthrobotrys cladodes isolated from decomposing wood, and Gamsylella gephyropaga (=Monacrosporium gephyropagum) isolated from soil. Gamundí and Spinedi18 used an entomology needle under optical microscope to collect conidia directly from fallen leaves, soil, wood, or sheep dung, and then inoculated Petri dishes. A different approach was used in the present study which allowed the isolation of a higher number of other predator and endoparasitic fungi despite the limited number of locations sampled.

Other studies conducted in the Americas have shown the cosmopolitan nature of nematophagous fungi. Several species were found in different substrates in Canada,3,10,30 such as soil, decayed wood, decayed plants, compost, and animal faeces. Estey and Olthof10 isolated from faeces only A. oligospora, A conoides and Dactylellina (=Dactylella) asthenopaga. However, a more recent survey in Eastern Canada30 studying cattle faeces in different state of decomposition revealed seventeen identified and one unidentified fungi. Ten of the identified ones have also been found in the current study, i.e. A. conoides, D. (=Arthrobotrys) flagrans, Arthrobotrys musiformis, A. oligospora, A. pyriformis, A. robusta, Catenaria anguillulae, D. coniospora, Podocrella harposporifera (=Harposporium anguillulae) and Myzocytium sp. Many studies in the United States of America have shown extensively over the years the presence of nematophagous fungi across the country, with examples from early to mid-twentieth century to these days.9,12,24,25,31–34,38 Sadly, though, no record seems to exist of any survey of these fungi isolated directly from faeces; those experiments using faeces as substrates for nematophagous fungi in that country relate only to efficacy trials, which is outside the scope of the present work. Lappe and Ulloa26 conducted the first survey in Mexico where A. oligospora and A. conoides were isolated. Later, Flores-Crespo et al.16 isolated nematophagous fungi from ovine and bovine faeces with the aim to evaluate the in vitro predacious capacity of eight autochthonous isolates, with A. oligospora, D. flagrans and Monacrosporium eudermatum among them; the first two species were also found in the current study. More recently, Acevedo-Ramírez et al.1 isolated several nematophagous fungi from different substrates such as soil, roots and ruminant faeces – ovine, bovine and caprine – in Mexico; the species identified were A. oligospora, A. musiformis, A. conoides, Arthrobotrys brochopaga, Arthrobotrys superba, Arthrobotrys kirghizica and G. gephyropaga (=M. gephyropagum). The first three species were also isolated in the present study although only A. oligospora coincides with the present study as isolated from ruminant faeces collected from soil; the other Mexican isolations from ruminant faeces were A. brochopaga and A. kirghizica. Búcaro4 isolated eighteen species in El Salvador from cultivated and non-cultivated soils from all fifteen soil groups present in that country. Although that screening was carried out contemplating the future use of nematophagous fungi as phytophagous, some species were the same ones identified in the present study and have potential for the control of gastrointestinal parasites in domestic animals, e.g. A. oligospora, A. musiformis, P. harposporifera (=Harposporium anguillulae) and S. grandis. The most frequently found species reported by Búcaro,4 i.e. Stylopage hadra, however, was not isolated in the present survey. Rubner39 isolated nine species of nematophagous fungi from soil at different altitudes and climatic conditions in Ecuador. Four species belonged to the genus Monacrosporium and five to the genus Arthrobotrys; among them, A. musiformis, A. conoides and A. oligospora were also found in the current study.

Persmack et al.37 isolated in Costa Rica Monacrosporium sp., A. musiformis, H. anguillulae, C. anguillulae and Acaulopage pectospora. Peraza-Padilla et al.36 also isolated several species of nematophagous fungi; among them, Monacrosporium sp. also was found in the present study. However, the two screenings mentioned above were only of soil samples from crop land and not livestock-rearing areas. Two other screenings for nematophagous fungi conducted in that country involved the collection of samples from a diversity of substrates such as various crop soils, soil, compost, dead leaves, and faeces from cattle, sheep, goats and horses. A. oligospora, A. (=Candelabrella) musiformis and Dactylella sp. were identified in the first of them.35 In the most recent study, Soto Barrientos et al.45 identified four species of nematode-trapping fungi – A. oligospora, A. (=Candelabrella) musiformis, A. conoides and A. dactyloides –, three species of egg-parasitic fungi – Trichoderma sp., Beauveria sp., Clonostachys sp. –, and one endoparasitic fungus, Lecanicillium sp. Neither of these two studies, however, makes it clear which of the nematophagous species, if any, were isolated from the sampled livestock faeces. Of all the thirteen species of nematode-trapping fungi isolated in Panama and Nicaragua,37 only a handful were also identified in the present study, i.e. Stylopage sp., A. conoides, A. musiformis, A. oligospora, and Monacrosporium sp.; however, all the endoparasitic fungi isolated here were also identified by Persmack et al.37. It is important to remark, though, that all samples in that Central America screening were only from crop soils. Saumell41 isolated in Brazil 293 fungi from cow pats and twenty-one species were identified, prevailing the network-forming species among the nematode-trapping fungi and the ingestible spores among the endoparasites. The most abundant species of nematode-trapping fungi were A. oligospora, A. musiformis and Monacrosporium leptosporum, while P. harposporifera (=H. anguillulae), Harposporium lilliputanum and Myzocitium sp. were the most abundant of the endoparasites. Subsequently, fungal isolations from fresh faeces were searched for, given that the fungal capacity of surviving gut passage in animals is a desirable characteristic. A total of ten isolates were found in fresh bovine faeces, the species identified being A. oligospora, M. eudermatum, H. lilliputanum, Gamsylella gephyropaga (=M. gephyropagum), A. musiformis, and Monacrosporium gampsosporum.42 Later on, Falbo et al.11 recovered four fungal isolates with predatory activity in Brazil but only two were identified, i.e. A. musiformis and A. conoides. Although none of them were isolated directly from livestock faeces, the former was found in soil samples from a commercial sheep property, while the latter was isolated from soil samples taken from a crop-livestock enterprise that included sheep. Both fungal species were also found in the present study.

All these studies in the Americas have contributed to the knowledge of several species of nematophagous fungi that could be considered for biological control of gastrointestinal parasites. Further studies would be needed to acquire in-depth knowledge of the characteristics of each fungal isolate and to test its potential as biological control agent against parasites.

The fact that as many as five fungal species found in the present study have not been described previously in the Western Hemisphere stresses the importance of finding nematophagous fungi species native to the region where biological control will be applied. Identifying species well adapted to particular livestock production regions is critical for implementing biological control using nematophagous fungi. D. flagrans and A. conoides, both identified in the present study, are among the most promising ones as biological control agents against gastrointestinal nematodes of ruminants.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

This project was partially financed by the Fondo para la Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (FONCyT-PICT No. 33132) of the Agencia Nacional de Promoción Científica y Tecnológica (ANPCyT).

Current address: Área de Parasitología y Enfermedades Parasitarias, Departamento de Sanidad Animal y Medicina Preventiva (SAMP), Facultad de Ciencias Veterinarias (FCV), Universidad Nacional del Centro de la Provincia de Buenos Aires (UNICEN), Centro de Investigación Veterinaria de Tandil (CIVETAN) – CONICET, Paraje Arroyo Seco, B7000 Tandil, Argentina.