During the COVID-19 pandemic, Rhizopus arrhizus and Rhizopus homothallicus were identified as causative agents of rhino-cerebral mucormycosis in COVID-19 patients. Clinical management typically includes surgical debridement and antifungal treatment, with amphotericin B (AMB) and posaconazole (PCZ) as primary options. However, long-term use of AMB can lead to toxicity, necessitating PCZ as a follow-up treatment.

AimsThis study aimed to examine the combined effect of AMB and PCZ on R. homothallicus.

MethodsThe combined effect of AmB and PCZ on R. homothallicus was studied by examining their minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values, fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI), spore germination properties, viability, and intracellular reactive oxygen species accumulation; Raman spectroscopy was also performed.

ResultsThe MIC values for AmB and PCZ were 4 and 8μg/mL, respectively, with a combined MIC of 2μg/mL and an FICI index of <0.28. The germination rates at MIC values after 48h of exposure were 28% for AmB, 36% for PCZ, and only 3% for the combination. Viability assays revealed dead sporangiospores following combination treatment. AmB and its combination generated more ROS (68.18% and 64.45%, respectively) than did PCZ alone (42.6%).

ConclusionsCombination therapy reduced the AMB dose without loss of efficacy, suggesting a synergistic effect against R. homothallicus. These results may support this alternative strategy to mitigate the side effects of AMB.

Durante la pandemia de COVID-19 se observó que Rhizopus arrhizus y Rhizopus homothallicus causaban mucormicosis rino-órbito-cerebral en pacientes con COVID-19. El tratamiento generalmente incluye desbridamiento quirúrgico y tratamiento antifúngico con anfotericina B y posaconazol como primera opción. Sin embargo, el uso prolongado de anfotericina B puede provocar toxicidad, lo que requiere el uso de posaconazol como tratamiento de seguimiento.

ObjetivosEste estudio examinó los efectos combinados de anfotericina B y posaconazol sobre Rhizopus homothallicus.

MétodosSe llevó a cabo un estudio de los efectos combinados de anfotericina B y posaconazol sobre Rhizopus homothallicus. Se evaluaron la concentración mínima inhibitoria (CMI), el índice de concentración inhibitoria fraccional (FICI), la germinación de las esporas, la viabilidad y la acumulación intracelular de especies reactivas del oxígeno (ROS); también se realizó espectroscopía Raman.

ResultadosLos valores de CMI para anfotericina B y posaconazol fueron de 4 y 8μg/ml, respectivamente, con una CIM combinada de 2μg/ml y un índice FICI<0,28. Las tasas de germinación del hongo a las 48h en las CMI fueron del 28% para la anfotericina B, del 36% para el posaconazol y solo del 3% para la combinación. Los ensayos de viabilidad mostraron esporangiosporas inviables después del tratamiento combinado. La anfotericina B y su combinación generaron más ROS (68,18 y 64,45%, respectivamente) que el posaconazol solo (42,6%).

ConclusionesLa terapia combinada redujo la dosis de anfotericina B sin perder eficacia, lo que indica un efecto sinérgico contra R. homothallicus; estos resultados avalan esta estrategia alternativa para mitigar los efectos secundarios de la anfotericina B.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, an increase of opportunistic fungal infections was observed in immunocompromised individuals. In India, approximately 40,000 cases of COVID-19-associated mucormycosis (CAM) were reported, mostly caused by Rhizopus species.29 Although the precise relationship between mucormycosis and SARS-CoV-2 infection is yet to be fully understood, certain factors, such as steroid use, uncontrolled blood sugar levels, neutropenia, and virus-induced immunosuppression, play an important role in the development of CAM.1 Mucorales, the group of fungi responsible for mucormycosis, thrives in decaying organic matter in the environment and enters the body through inhalation, causing severe infections in immunocompromised hosts.44 In India, rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis is the most commonly observed form of the disease; pulmonary, gastrointestinal, and cutaneous cases have also been reported.15Rhizopus is the most frequently observed cause of mucormycosis; however, other Mucorales species, such as Apophysomyces, Mucor, Rhizomucor, and Saksenaea, have also been associated with this disease.15,43 During the pandemic, Rhizopus homothallicus was reported to cause rhino-orbital mucormycosis, although the number of cases was lower than that associated with Rhizopues arrhizus.21R. homothallicus produces numerous zygospores with unequal suspensor cells and can withstand high temperatures of up to 48°C.30 First identified in 1961, R. homothallicus was primarily isolated from environmental sources and has now been noted as a significant cause of mucormycosis in humans.37 Treatment of R. homothallicus infections involves surgery, addressing underlying predisposing risk factors, and administering antifungal drugs.31 Liposomal amphotericin B (AMB) is the preferred treatment, whereas posaconazole (PCZ) and isavuconazole are secondary options.16 High doses of liposomal AMB are associated with increased levels of nephrotoxicity and electrolyte imbalances. A reduction in dosing is necessary because in 40% of individuals with baseline serum creatinine concentration those baseline levels are doubled. Despite the lack of evidence supporting higher AMB dosages for mucormycosis, they may be used on an individual basis, particularly in cases with central nervous system or osteoarticular involvement.10,24 Current guidelines discourage the use of antifungal drug combinations as the first choice because of insufficient evidence of their efficacy.22 However, laboratory studies have suggested the potential benefits of combinations of AMB with caspofungin (CAS), PCZ with CAS, and isavuconazole with CAS.25 Despite these recommendations, the effects of antifungal drugs on R. homothallicus remain unclear. Our research aims to address this critical knowledge gap by seeking to understand the effects of the antifungals AMB and PCZ, alone and in combination, on R. homothallicus spores. This study is indispensable for developing effective strategies against R. homothallicus infections. The insights gained from this study may enhance our knowledge of fungal treatment, paving the way for improved therapeutic approaches in the future.

1Materials and methods1.1MaterialsThe chemical compounds used in this study, amphotericin B (from Streptomyces, A-4888-100MG vial, purity 80%, powder), posaconazole (SML2287-5MG vial, purity 98% analytical grade), and propidium iodide, were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Mumbai, India). Fungal culture media, Sabouraud Dextrose Agar, and RPMI-1640 without sodium bicarbonate, were obtained from Hi-Media Laboratories Limited (Mumbai, India). Tarson Product Private Limited (Kolkata, India) supplied plastic wares, which consisted of pre-sterilized 50mL Falcon tubes, 1.5mL Eppendorf vials, and 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates. The solvents used in the experiments were acquired from Merck Life Science Private Limited (Bangalore, Karnataka, India). All reagents used in this study were of analytical grade quality, and each experiment was performed in triplicate.

1.2Fungal strain and culture parameterWe obtained a clinical strain of R. homothallicus from a 45-year-old woman with COVID-19-associated mucormycosis affecting the left maxillary sinus. The Institutional Ethical Committee at the Institute of Medical Science, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi approved this study (Dean/2021/EC/3003, dated October 29, 2021). We identified the isolated R. homothallicus strain using standard mycological protocols, including culture growth characteristics, ability to grow at 48°C, and presence of numerous zygospores with unequal suspensor cells. We then subcultured the identified strain in Sabouraud dextrose broth and stored it at −80°C in a medium containing 25% glycerol for future experiments.

1.3Harvesting of sporangiosporesR. homothallicus isolate was preserved and subcultured on Sabouraud dextrose agar slant for 4–6 days at 37°C. The sporangiospores of R. homothallicus were harvested according to the method outlined by Singh et al. in 2011.21 Ten milliliters of 0.9% saline solution with 0.01% Tween-20 was added to the slant tube, and the sporangiospores were collected and washed three times with saline solution. The resulting suspension was centrifuged at 3500×g for 8min to obtain a pellet. The pellet was then washed with 0.1M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and reconstituted in 0.9% saline solution. The number of sporangiospores was determined using a Neubauer hemocytometer, and quantification was expressed as sporangiospores/mL.

1.4Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination of antifungals against R. homothallicusThe MIC values for AmB, PCZ, and their combination (AmB+PCZ) against R. homothallicus were determined according to the CLSI M38 A3 guidelines by performing two-fold serial dilutions in a sterile, flat-bottom 96-well microtiter plate.7,9 A working drug solution of 32μg/mL for both drugs was prepared, and 100μL of the drug suspension was dispensed into the wells using a double-dilution method in RPMI-1640 with MOPS buffer, resulting in a drug concentration range of 0.03–16μg/mL. Subsequently, 100μL of the fungal sporangiospores containing 0.5–5×104sporangiospores/mL was added to each well, and the plates were incubated 72h at 37°C. After 72h of incubation, the wells were observed for any turbidity. The MIC values of the drugs were determined as the drug concentration that completely inhibited the germination of sporangiospores.

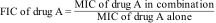

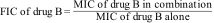

1.5Checkerboard assay for synergyTo evaluate the interaction between the two drugs, a checkerboard assay was performed in accordance with a previous study by Odds et al.26 Briefly, RPMI-1640 medium containing AMB at concentrations ranging from 32μg/mL to 0.125μg/mL was added to the wells in columns one through nine of a 96-well microtiter plate; RPMI-1640 medium containing PCZ at concentrations ranging from 32μg/mL to 0.5μg/mL was added to the wells in rows A–H. A 100μL sporangiospores inoculum was then added to each of the wells, and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 72h. Growth inhibition was determined visually, and the FICI model was used to interpret the drug interaction according to the following formula:

The results were interpreted as follows: FICI <0.5, synergistic effect; FICI 0.5–4, indifferent effect, and FICI >4, antagonist effect.

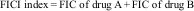

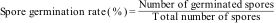

1.6Studies on the inhibition of germination of sporangiospores of R. homothallicusR. homothallicus sporangiospores were obtained following established protocols. Subsequently, an inhibition assay on sporangiospores germination was conducted as previously described.45 Briefly, 100μL of sporangiospores suspension (107spores/mL) were exposed to AMB, PCZ, and a combination of drugs (AMB and PCZ) at their MIC values in separate tubes. Negative controls consisted of sporangiospores suspensions in 100μL of distilled water, incubated at 37°C. Twenty microliters of RPMI-1640 suspension containing drugs and sporangiospores were placed on sterile concave slides after every 2h of incubation until 48h. There were three slides for each treatment, and the mean values were compared statistically. During the observation, a hundred sporangiospores per slide were examined using a bright-field binocular compound light microscope (Olympus) at 400×. The spore germination rate (%) was determined using the following formula:

1.7Confocal laser scanning microscopyConfocal microscopy was used to evaluate sporangiospores viability after exposure to AMB, PCZ, and their combination following propidium iodide staining.14,45 Sporangiospores suspensions (2×107sporangiospores/mL) were treated with 100μL of each antifungal agent at their respective MICs, with distilled water as the negative drug control. The samples were then incubated at 37°C for 10h, followed by withdrawal of 1mL aliquots and centrifugation at 3500×g for 8min. The pellets were washed thrice with PBS and resuspended in fresh PBS for further analysis. The sporangiospores were then stained with 10μL of 1mg/mL propidium iodide (PI) (excitation/emission: 535nm/617nm) for 30min in the dark. Excess dye was removed by washing with PBS. The samples were evaluated using an SP5 AOBS Super resolution laser scanning confocal microscope (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) with a 40× immersion oil objective lens. Antifungal activity was evaluated by identifying dead sporangiospores with damaged membranes stained red with PI; live sporangiospores remained unstained due to the presence of intact membranes. This method, based on visualization via confocal microscopy, provided insights into the membrane-damaging effects of AMB, PCZ, and their combination on sporangiospores viability.

1.8Flow cytometry studies for endogenous ROS generation activityThe production of endogenous reactive oxygen species (ROS) in R. homothallicus after 10h exposure to AMB, PCZ, and the combination of both drugs was evaluated using flow cytometry with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate (DCFH-DA) as the marker for ROS. After 10h of incubation, the treated sporangiospores were washed twice with PBS at pH 7.2 and resuspended in fresh PBS to a density of 106sporangiospores/mL. The sporangiospores were then labeled with 5μM DCFH-DA for 30min, and the measurement of endogenous ROS using a BD Accuri C6 Flow cytometer was performed. Data were collected using BD Accuri C6 software, which utilizes light scatter and fluorescence signals generated by a 20mW laser with an illumination wavelength of 488nm. The measurements were taken logarithmically with a low sample rate of 14μL/min; in this method, 104 sporangiospores per sample were tested, providing a comprehensive analysis of ROS production.

1.9Raman spectroscopyFor Raman spectroscopy, sporangiospores treated with AMB, PCZ, and the combination (AMB+PCZ) at their respective MICs, as well as untreated sporangiospores, were centrifuged for 5min at 3500rpm. The resulting semisolid pellets were deposited on glass slides and dried under ambient conditions. Subsequently, Raman measurements were performed using a CRM Alpha 300S instrument (WI Tec GmbH, Ulm Germany). The excitation source employed in this study was a 532nm Nd-YAG laser with a maximum power output of 40mW. The laser power was attenuated to ∼10mW at the sampling point. The measurements were undertaken using a 100× objective, and the dispersed light intensity of the signal from the grating was detected using a Peltier-cooled charge-coupled device (CCD). The Raman measurements encompassed a maximum laser exposure area of 750μm. The spectra were acquired using a spectral window of 400–2100cm−1.13

1.10Statistical analysisUsing statistical analysis, we justified our findings by incorporating a 5% error bar in the bar graph representation. Origin software 8.4.2 (Origin Lab, Northampton, USA) was used to determine the mean and identify outliers in the germination data, followed by One-way ANOVA applied to calculate the statistical significance using GraphPad Prism 8.

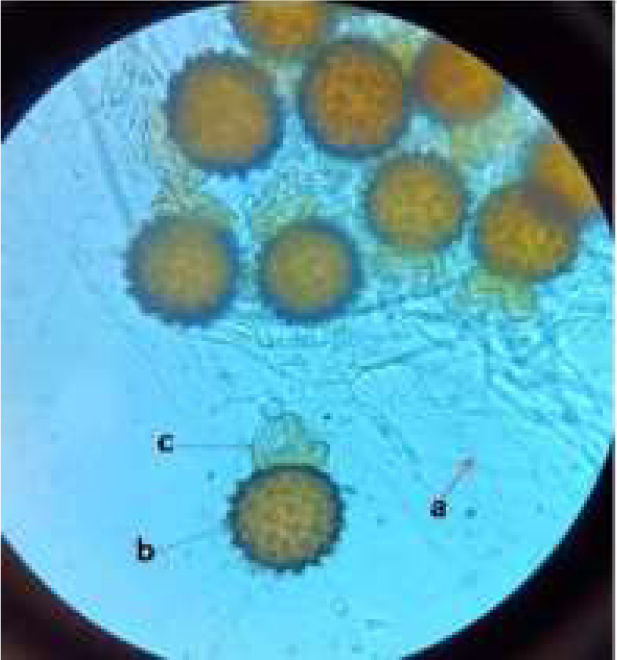

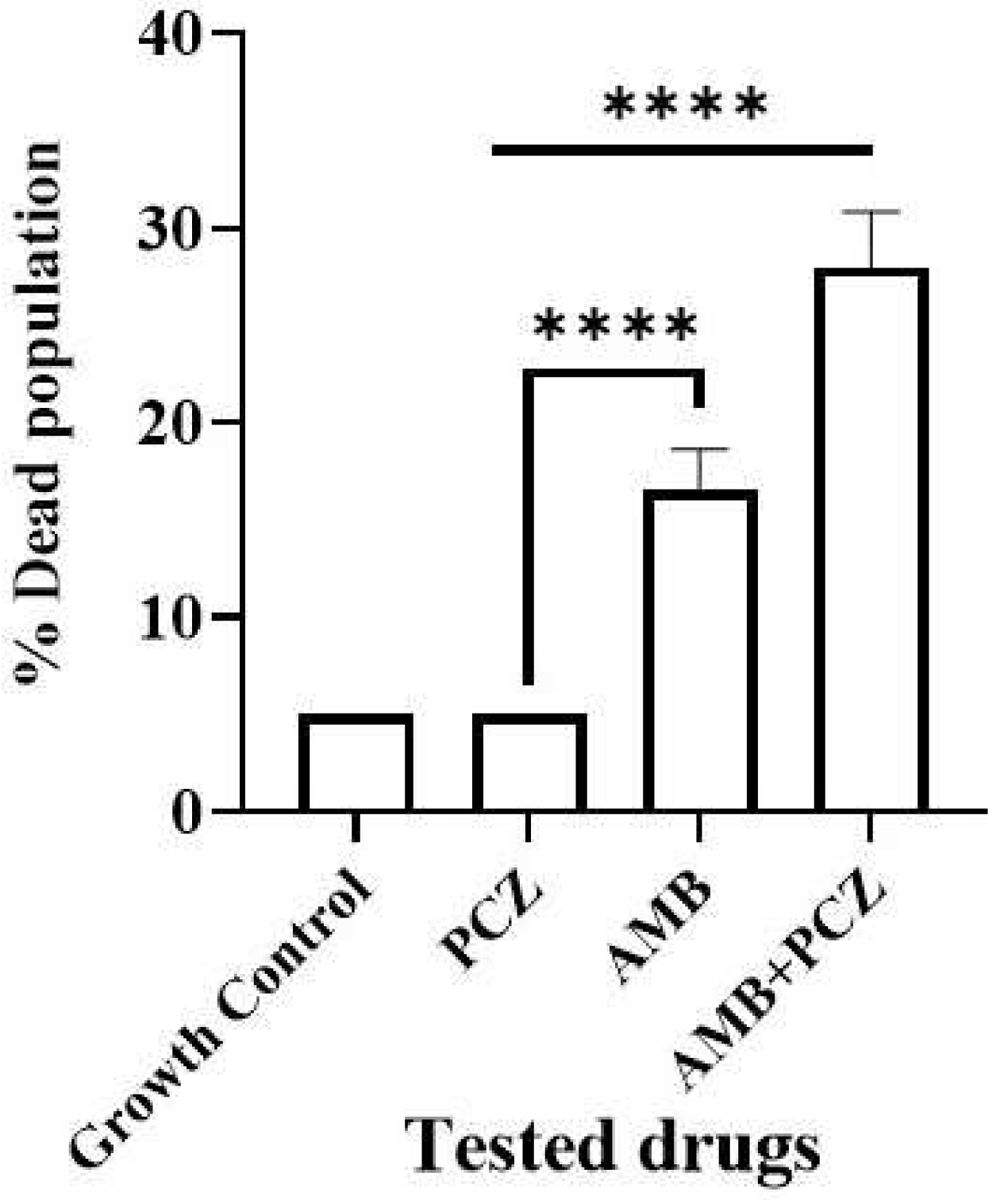

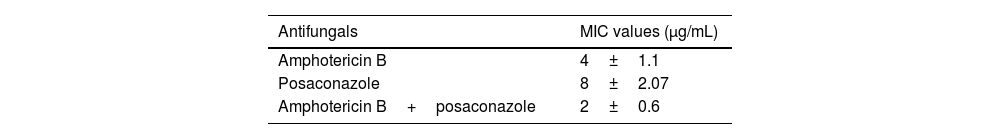

2Results2.1MIC determinationThe clinical isolate of R. homothallicus isolated from a patient with COVID-19-related mucormycosis was grown on routine SDA media and exhibited fluffy white colonies after 72h of incubation. Upon examination using a lactophenol cotton blue wet mount, we observed broad non-septate hyphae with numerous zygospores, as well as a sexual form characterized by unequal suspensor cells on each side (Fig. 1). The MIC values for AMB and PCZ against the tested strains of R. homothallicus were 4 and 8μg/mL, respectively, while combined MIC (AMB+PCZ) was determined to be 2μg/mL, as indicated in Table 1.

Lactophenol cotton blue wet mount of clinical R. homothallicus strain (a, non-septate hyphae; b, zygospore and c, uneven suspensor cell) isolated from rhino-orbital sample of a female patient diagnosed with COVID-19 and mucormycosis, hospitalized at Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India. The image was captured using bright-field binocular compound light microscope (Olympus) at 400×.

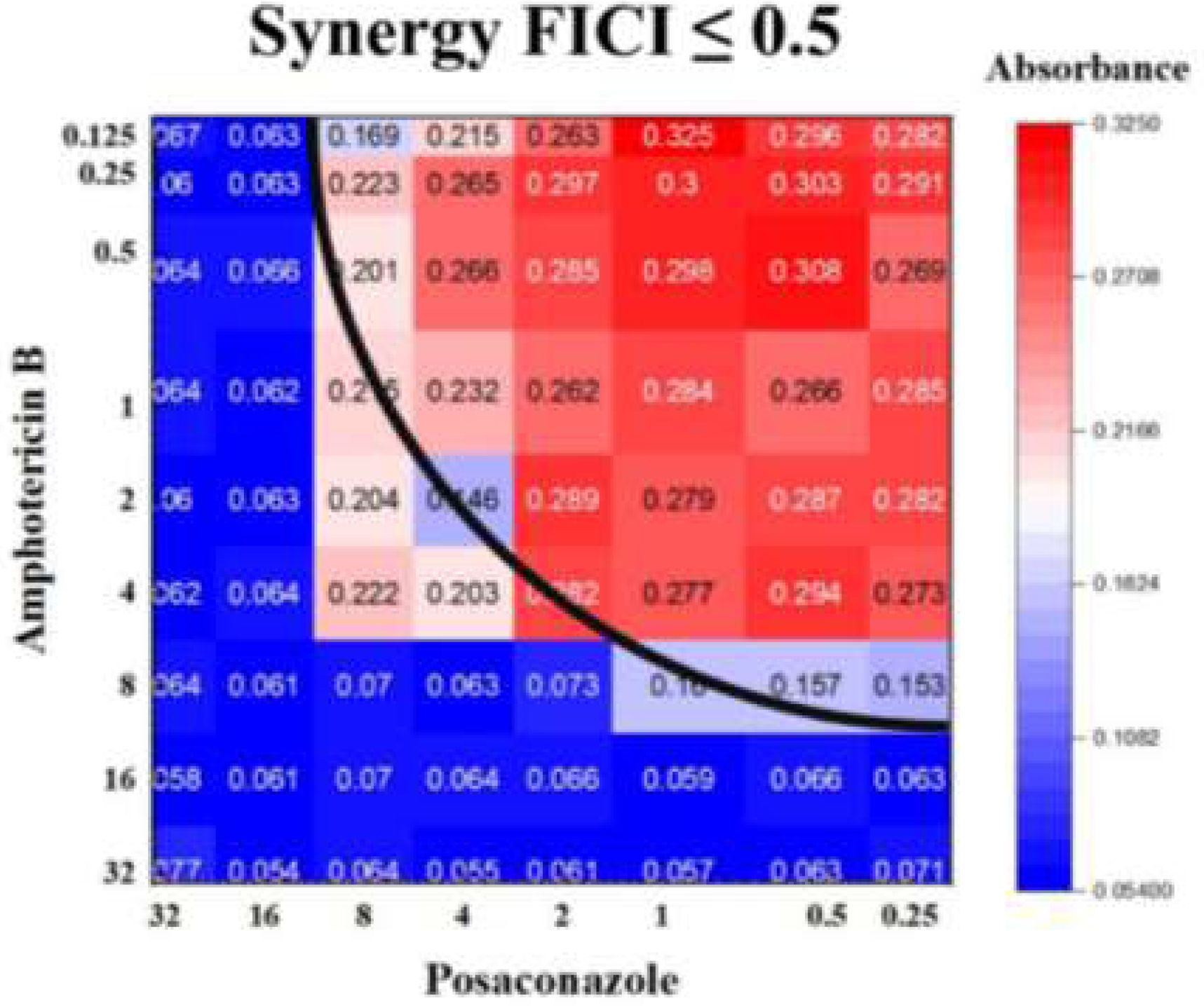

The synergistic effect of AMB and PCZ was determined using the checkerboard method, and FICI was calculated. The MIC of AMB alone was 4μg/mL, whereas its combination with PCZ resulted in a remarkably low MIC (0.125μg/mL). Similarly, the MIC of PCZ alone was 8μg/mL, whereas its combination with AMB showed a MIC of 2μg/mL (Fig. 2). The FIC values for AMB and PCZ were 0.03125 and 0.25, respectively; the FICI value of 0.28 (<0.5) suggested synergistic effects, as shown in Fig. 2.

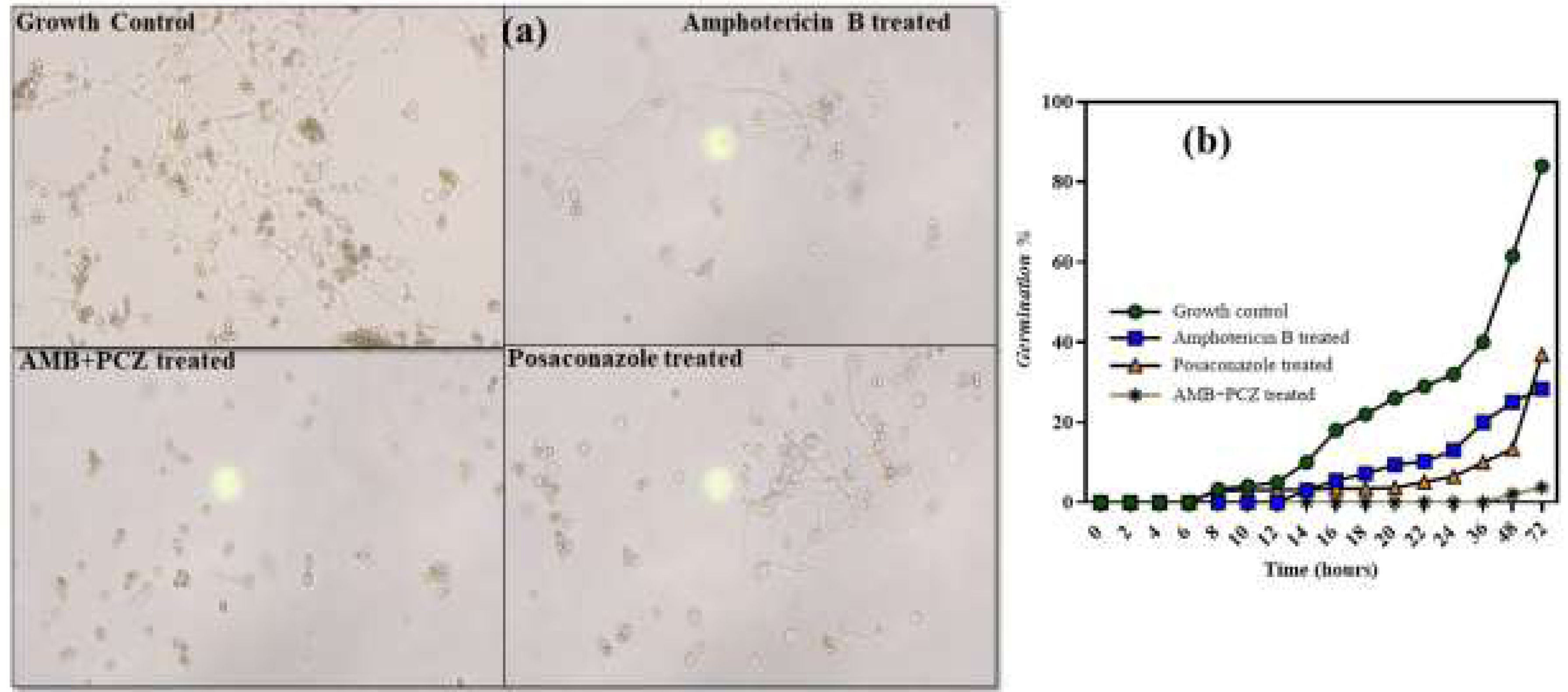

2.3Inhibition of sporangiospores germinationWe evaluated the impact of antifungal drugs on sporangiospores germination by counting the number of germinated R. homothallicus spores at various intervals (Fig. 3). After 10h of incubation under controlled conditions, the sporangiospores diameter was increased to 15–18μm, and a germ tube developed.12 Germination inhibition assays revealed that the control group (no antifungal agents) showed less than 10% germination at 24h, which increased to 60% by 48h. AMB treatment maintained a low germination rate of 28% at 48h, suggesting an inhibitory effect. Similarly, the combined (AMB+PCZ) treatment, with antifungals concentrations at the MIC value, inhibited germination at a very low concentration of 3% at 48h, suggesting a strong synergistic effect. PCZ alone resulted in slightly higher germination (36.85%) than that with AMB, but exhibited significant inhibition compared to the control. Notably, the combination of AMB and PCZ had the most significant inhibitory effect, maintaining minimal germination for over 48h. Thus, further studies are required to elucidate these mechanisms and optimize the antifungal dosing.

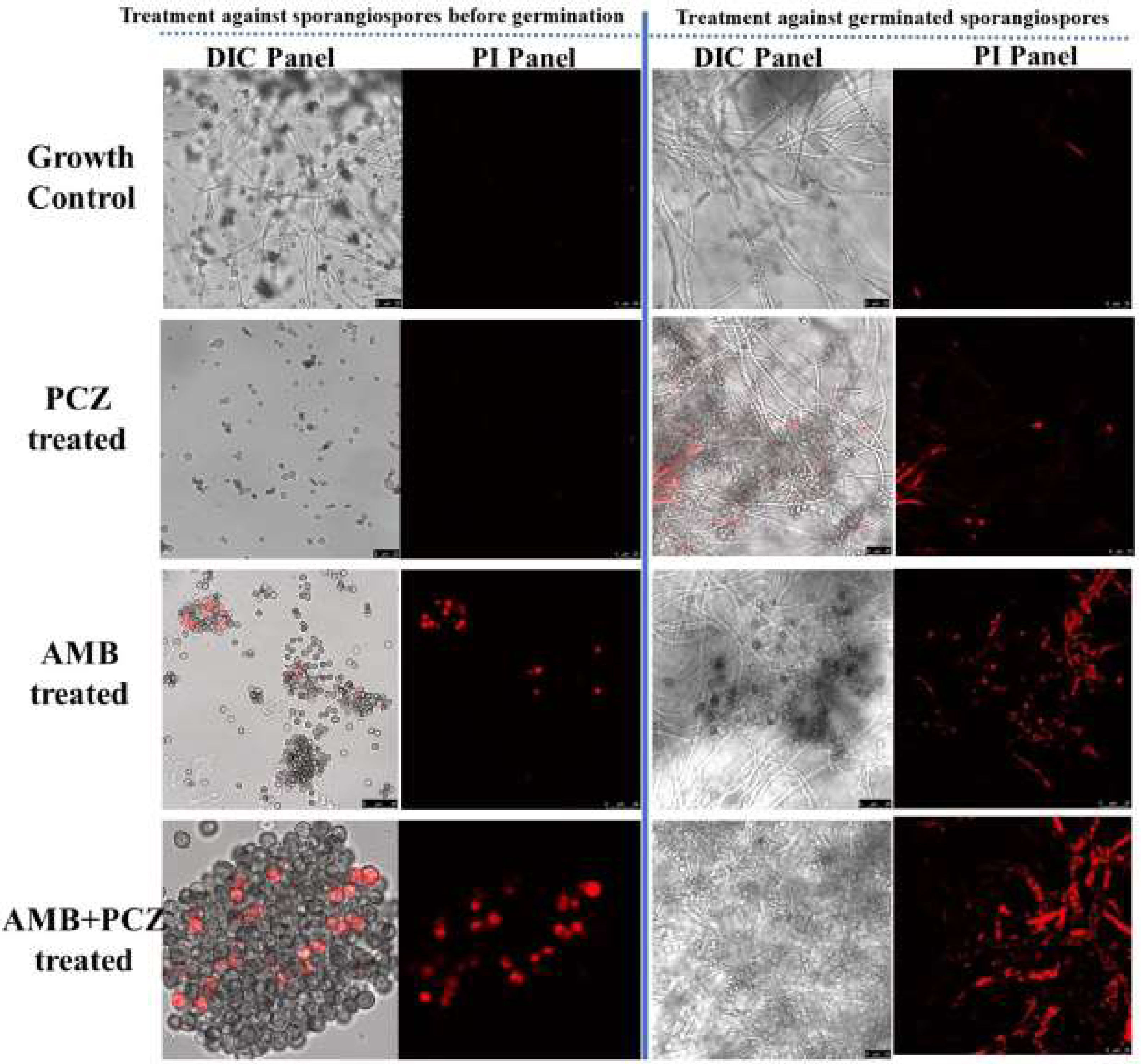

2.4Viability studies of antifungal-treated sporangiosporesConfocal microscopic study confirmed the sporangiospores viability of R. homothallicus through live-dead imaging. The inoculum of freshly prepared sporangiospores was treated with drugs at their respective MIC values for 10h. Fig. 4 (panel a) shows the treated sporangiospores along with the untreated control, while panel (b) represents the mycelium treated with drugs. The results suggest that sporangiospores treated with both AMB and AMB+PCZ had a higher dead rate (16% and 27%, respectively; Fig. 5) than the sporangiospores treated with PCZ or the ones in the control group (5%; Fig. 5). It is noteworthy that the combination of drugs had a more pronounced killing effect than antifungals used alone. Interestingly, the tested drugs had a greater level of killing action against completely germinated sporangiospores (against mycelium) as shown in Fig. 4 (treatment against germinated sporangiospores).

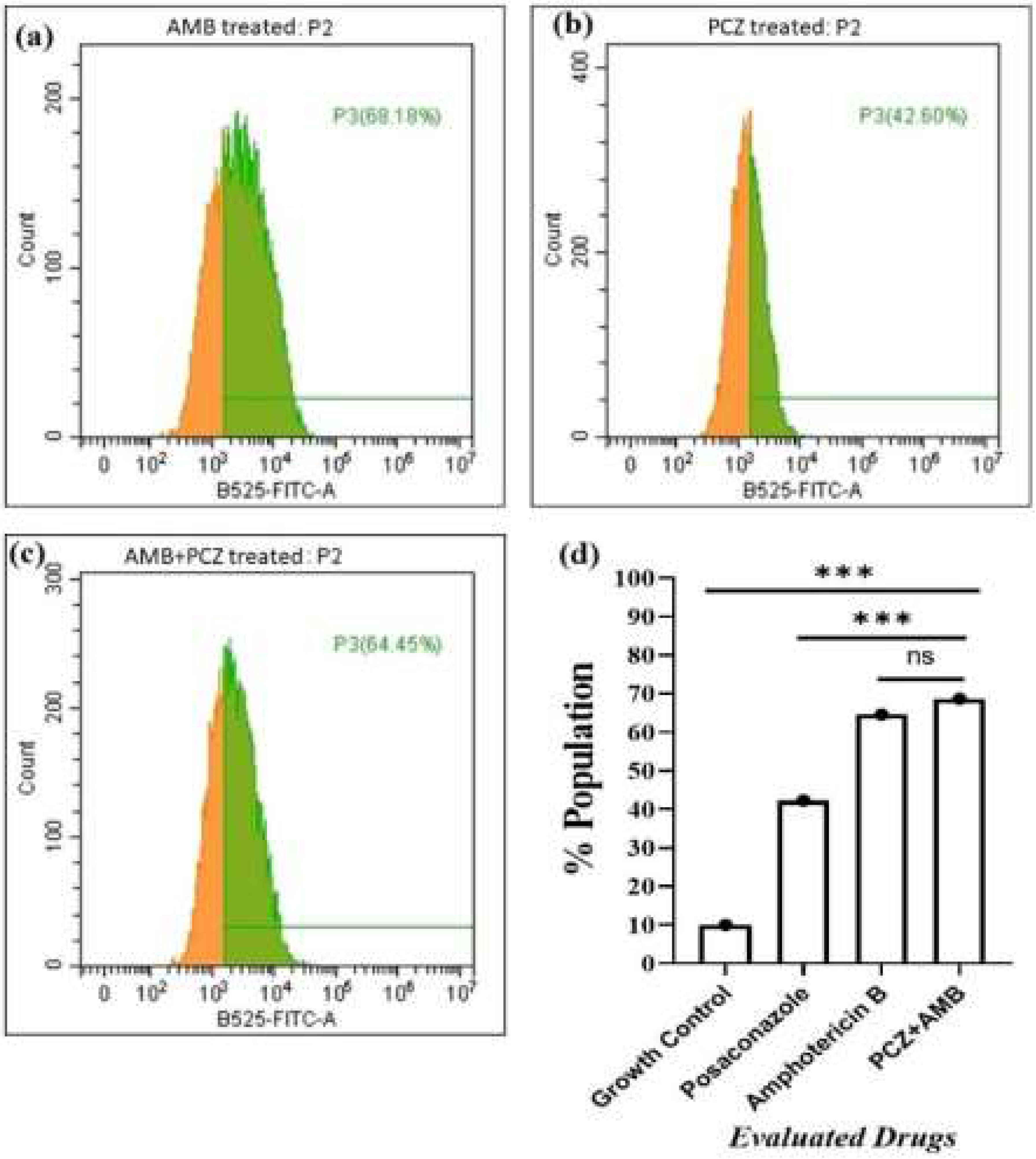

Endogenous ROS accumulation in the sporangiospores treated with AMB, PCZ, and AMB+PCZ was observed via significant shifts in DCF fluorescence using flow cytometry, as shown in Fig. 6. After 10h of treatment, ROS rate within the sporangiospores exposed to AMB, PCZ, and AMB+PCZ was 68.18%, 42.60%, and 64.45%, respectively, compared to a value of 10.7% in the growth control, demonstrating a significant induction of endogenous ROS generation in the sporangiospores after the antifungal treatment.

FACS data of the effects of antifungal exposure on the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by R. homothallicus sporangiospores: (a) amphotericin B treated; (b) posaconazole treated; (c) AMB+PCZ treated, and (d) graph showing statistical significance (One-way ANOVA, adjusted p-values), ns=non-significant, ***p≤0001.

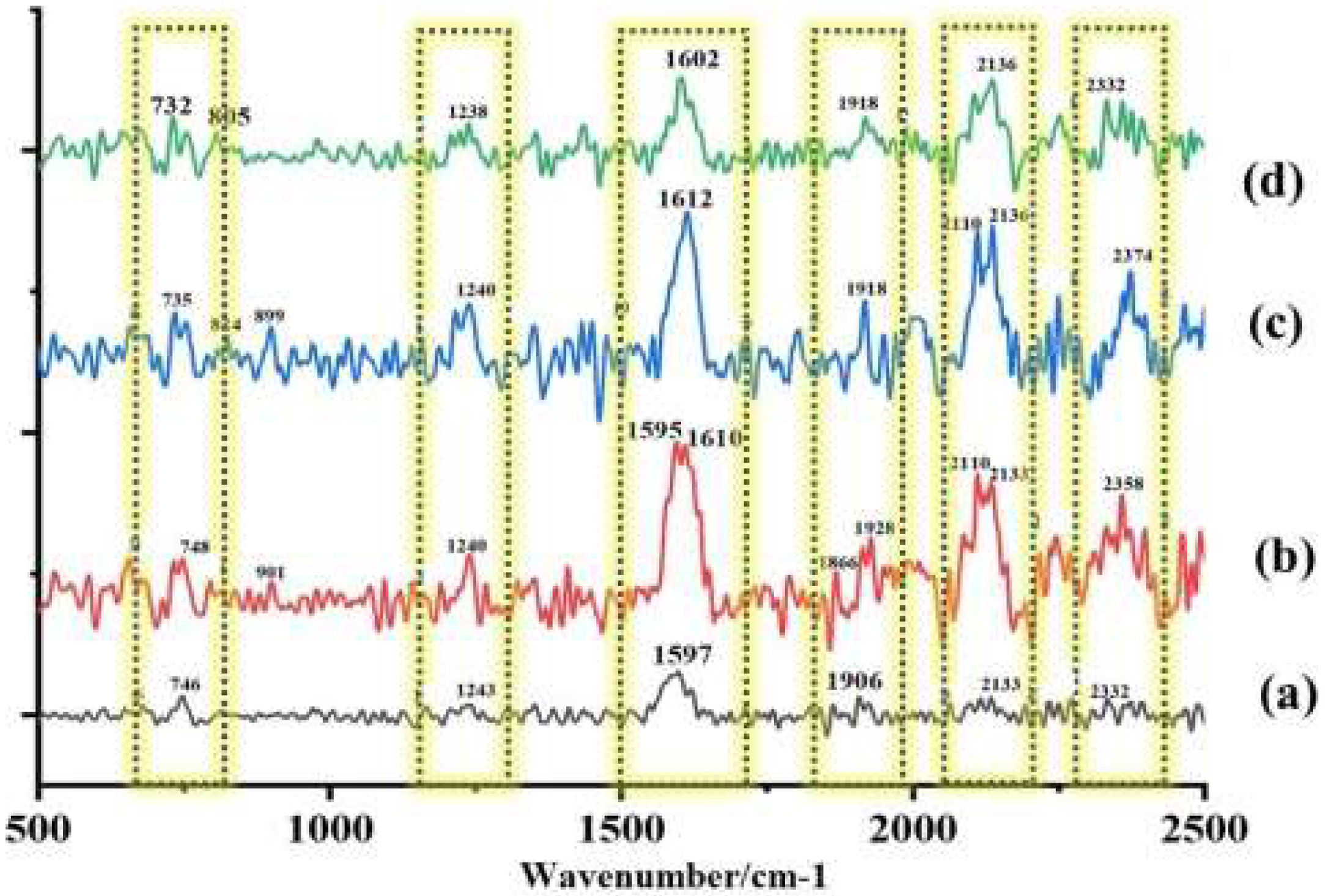

Raman spectroscopy is a useful tool for studying the spatial arrangement of biological macromolecules. It is used to detect the spectral features of molecules by measuring high-frequency inelastic light scattering. When healthy cells are exposed to antifungal drugs, changes in the structural conformation and content of macromolecules, such as modifications to the nucleic acid phosphate backbone and protein hydrogen bonds, result in alterations in the Raman spectra.17,23 By applying this approach to R. homothallicus sporangiospores, significant architectural modifications were observed in response to AMB, PCZ, and AMB+PCZ. Untreated sporangiospores (Fig. 7a) showed a few significant Raman bands that appeared in the fingerprint region at 746 and 1243cm−1, which represent the presence of DNA (ring breathing vibration of thymine base) and the amide III of unfolded protein structures that are present in the sporangiospore cell wall. Further, the band at 1597cm−1 strongly suggests the presence of the carotenoid or lipid component of the cell wall; the band at 1906cm−1 is unidentified. The band at 2133cm−1 may be associated with the stretching of the carbon-nitrogen triple bond. This functional group, while not a primary structural component of sporangiospores, has been identified in some fungal metabolites. After being treated with AMB, PCZ, and AMB+PCZ, bimodal peaks were noted at 746, 1243, 1597, 1906, and 2133cm−1, indicating that the antifungal agents induced significant molecular or structural changes in the fungal sporangiospores components (as shown in Fig. 7b–d).

3DiscussionR. homothallicus has rarely been identified as a drug-resistant fungal species in human infections.32 The treatment of severe rhino-cerebral or pulmonary R. homothallicus infection involves surgical intervention and potent antifungal medications such as AMB, PCZ, and isavuconazole. In contrast, voriconazole and echinocandins are less effective.40 The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) guidelines published in 2014 recommended liposomal AMB and PCZ for mucormycosis as the first antifungal therapy based on moderate- and low-quality evidence, respectively.41 Liposomal AMB and isavuconazole are the primary medications that have been studied for the early treatment of mucormycosis; however, the overall mortality rate is still high, while posaconazole is typically used as a secondary treatment option.10,46 Recently, posaconazole has been shown to be effective as a salvage therapy for disseminated zygomycosis; however, few studies have been conducted, and a search for novel therapeutic strategies remains necessary. Thus, the combination of antifungal agents with different mechanisms of action could be an interesting therapeutic option for improving clinical outcomes. Combination therapies are often prescribed for immunocompromised patients, offering benefits such as synergistic effects and more extensive coverage of the infection than monotherapy.39 Combining antifungal agents may reduce the risk of developing resistance, like in monotherapy treatments, and enables dose reduction of antifungal agents that may cause significant side effects (such as polyenes). The synergistic or additive antifungal activity in combination therapy enables shortening treatment duration.8,20 However, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) 2016 guidelines do not recommend the use of AMB in combination with azoles or echinocandins for the treatment of mucormycosis.2 Unfortunately, little information is available on the in vitro effects of antifungal combinations against zygomycetes. Only the associations of AMB with flucytosine, and terbinafine with AMB or triazoles, have been evaluated. However, a recent study reported that the combination of AMB with other antifungal agents (e.g., PCZ or itraconazole) can lead to synergistic effects against Rhizopus spp.3,19 Notably, similar results were observed in this study using the antifungal susceptibility assay. When AMB and PCZ were tested in combination, the MIC of AMB was significantly reduced, as shown in Table 1, compared to monotherapy. Similarly, Rudramurty et al. reported the MIC ranges of various antifungals, including AMB, itraconazole, isavuconazole, and terbinafine, as 0.03–16μg/mL. In contrast, posaconazole exhibited a MIC range of 0.03–8μg/mL against different Rhizopus spp.30

Recently, Ballester et al. described a synergistic interaction between AMB and PCZ in R. microsporus var. rhizopodiformis.3 In our case, a FICI score <0.5 suggested that the drugs performed better in combination than alone, demonstrating a synergistic effect against the sporangiospores of a clinically isolated strain of R. homothallicus, as shown in Fig. 2. Rodriguez et al. reported a similar FICI value in an in vivo study after combining AMB with PCZ against Rhizopus oryzae.33 Furthermore, Rickerts et al. reported that a patient with disseminated mucormycosis caused by Rhizopus spp. was successfully treated with combination therapy with PCZ and AMB, obviating the need for surgical biopsy.34 Accordingly, the FICI score of 0.28 against R. homothallicus of our study supports the validity of this approach. This finding suggests that combination therapy can reduce the AMB dose without loss of efficacy.

The experiment on how antifungals affect sporangiospores germination by counting the number of germinated R. homothallicus sporangiospores over different time periods (0–72h) has provided a key medical insight. As the process of germination is essential for the disease progression, it could offer fungal-specific targets for developing new antifungal therapies. By developing compounds that inhibit germination, we can create effective, low-toxicity medications to prevent or treat diseases caused by fungal spores. Consequently, AMB, PCZ, and the combination of AMB+PCZ showed, based on the MIC of each drug compared to the untreated control, different levels of inhibition on sporangiospores germination (Fig. 3). The viability of treated sporangiospores was assessed using propidium iodide staining, followed by confocal microscopy, revealing intriguing results (Fig. 4): PCZ exhibited fungistatic effects on the sporangiospores, while showing significant fungicidal activity against germinated sporangiospores or mycelia (Fig. 4, plate b). AMB-treated (10h) sporangiospores showed a 16±2% dead rate compared to PCZ (5%) and AMB+PCZ (27±3%), as shown in Fig. 5. Notably, PCZ demonstrated fungistatic activity against sporangiospores but was active against mycelium, as shown in Fig. 4. Similarly, Perkhofer et al. reported that under in vitro conditions, PCZ and AMB were substantially more synergistic (40%) against hyphae (p<0.05) than against sporangiospores of zygomycetes (10%).27 Therefore, it is plausible to assume that the processes that hinder sporangiospores germination differ from those that hinder the growth of hyphae. These findings may be explained by differences in sterol content, fungal cell membrane transporters, and cell wall composition between conidia and hyphae. Additionally, our research revealed that AMB-treated sporangiospores exhibited higher endogenous ROS generation (68.18%) than those treated with PCZ (42%), as shown in Fig. 6. However, there was no significant difference between the sporangiospores treated with AMB and those treated with the AMB+PCZ combination (64.45%). ROS play a crucial role in physiological processes, and any imbalance can lead to excessive ROS production.38 Numerous studies have demonstrated that the antifungal effects of AMB are due to its ability to induce ROS production and form pores by binding to the ergosterol of the cell membrane, which is considered a dual mode of action, ultimately causing oxidative damage and fungal cell death.18,35,47 In our case, an increase in endogenous ROS confirmed the fungicidal properties of both AMB alone and the AMB+PCZ combination against R. homothallicus sporangiospores.36 Interestingly, the proportion of dead sporangiospores following treatment with AMB, PCZ, and the AMB+PCZ combination was lower than that of ROS accumulation experiment. Additional research is necessary to better understand the physiological state of sporangiospores after exposure to antifungal agents. In our case, an increase in endogenous ROS confirmed the fungicidal properties of both AMB alone and the AMB+PCZ combination against R. homothallicus sporangiospores.

Raman spectroscopy is a rapid, non-destructive method that requires a small sample, and provides clear spectral bands, which is a distinct advantage over the often unclear results of infrared spectroscopy.28 Our study identified molecular changes in the sporangiospores of R. homothallicus treated with PCZ, AMB, and AMB+PCZ (Fig. 7). In untreated control sporangiophores, the Raman band at 746cm−1 shifted to a bimodal peak after the treatment with AMB, PCZ, and AMB+PCZ, with different intensities. This biphasic shift in the Raman spectra of fungal conidia after AMB treatment is due to AMB binding to ergosterol, causing conformational changes in the polyene chain, which are influenced by ergosterol in the fungal membrane. These peaks may represent different states of the AmB-ergosterol complex or drug conformations within the membrane.48 The complex bimodal shape around 748cm−1 in the Raman spectrum of PCZ-treated sporangiospores likely arises from the vibrational contribution from the drug and the stress response of the fungal cells to the drug. This finding could result from conformational changes due to PCZ integration, resonance Raman effects during laser excitation, or spectroscopic heterogeneity, indicating different microenvironments within sporangiospores. The region between 1200 and 1500cm−1 in a Raman spectrum is known as the “local symmetry” zone, which is dense with complex vibrations, making precise assignments challenging. However, the shift in the peak at 1243cm−1 after treatment with AMB, PCZ, and AMB+PCZ may be associated with significant protein denaturation or misfolding, increasing the proportion of random coils or β-sheet structures. This increase in the disordered protein structure can result in a more pronounced or altered amide III band at 1240cm−1. Since ergosterols are the primary sterol in Mucorales cell membranes, the appearance of an intense and bimodal peak in treated sporangiospores at 1597cm−1 (untreated control) might be due to the conjugated carbon-carbon double bonds in a six-membered ring. When AMB/PCZ binds to ergosterol, it can induce structural changes and shift this peak, as shown in Fig. 7.4 The significant Raman shifts between untreated sporangiospores and antifungal-treated sporangiospores plausibly indicate multi-target action of drugs and molecular changes at their target site.17 As fungal conidia/sporangiospores are highly dynamic and contain species-specific metabolic markers, characterizing R. homothallicus sporangiospores using Raman spectroscopy is associated with several challenges, mainly due to strong autofluorescence, the complex nature of their biochemical composition, and issues associated with sample preparation. These factors can result in spectra that are both faint and intricate, obscuring the Raman signals that allow for a more detailed analysis.

4ConclusionsThis study highlights the combined effect of AMB and PCZ, which enables the use of lower AMB doses against R. homothallicus. This therapeutic combination has the potential to mitigate the severe side effects associated with extended antifungal treatments. This study evaluated the effectiveness of drugs and mechanistic elements, including ROS production and chemical alterations, as identified through Raman spectroscopy, providing deeper insights into drug-pathogen interactions. Our findings demonstrate that the combination of AMB and PCZ led to a reduced MIC and synergistic effects, confirming their enhanced effectiveness. Furthermore, the synergistic interaction between AMB and PCZ offers valuable insights into future treatment strategies against infections caused by environmental sporangiospores, particularly R. homothallicus. Although the study was limited by its in vitro nature, the results may not directly translate to in vivo conditions; further research and clinical trials are needed to establish clinical outcomes. Focusing on a specific clinical strain may restrict the applicability of this work to other strains that cause mucormycosis. Long-term use of antifungal combinations could lead to resistance, which was not addressed in the present study. Although this study suggests that lower drug doses can reduce toxicity, comprehensive toxicity data and comparisons with single-drug in vivo therapies are lacking. Although Raman peak shifts were observed, a precise interpretation linking these shifts to specific biochemical changes would be beneficial. Future research using supervised classification may be used to identify molecular biomarkers associated with the observed spectral patterns. Additionally, a detailed investigation is needed to better understand the antifungal mechanisms for sporangiospores.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAN and AKT contributed equally to this study. Conceptualization: AKT and MKG; Data curation: AN and SG; Formal analysis: AKT; Funding acquisition: MKG, AN, and SG; Investigation: AN and AKT; Methodology: AN, MKG, and RT; Project administration: MKG, RT, and MB; Resources: MKG and RT; Software: AKT and AN; Supervision: MKG and RT; Validation: AKT and MKG; Visualization: AN, AKT, and MKG; Roles/Writing – original draft: AN and AKT; Writing, review and editing: AKT, MKG, and RN. All of the authors reviewed and agreed to this submission.

Ethical statementThe research was conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the institutional ethical committee regulations, and the study was approved (Dean/2021/EC/3003, dated October 29, 2021).

Informed consentInformed consent was obtained from the individual included in the study according to regulations of Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University (Varanasi), India.

FundingThis work was partially supported by an Incentive Grant under IoE to Dr. MK Gupta (R/Dev/D/IoE/seed & Incentive grant_III/2022-23/49235).

Conflicts of interestThere are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Uncited referencesThe authors would like to thank the Central Discovery Centre (CDC), Banaras Hindu University for providing access to flow cytometry, Raman spectroscopy, and SATHI BHU for laser scanning super-resolution microscopy. The authors are also thankful to the Mycology Research Group for their consistent support during this study.