The state of the art and future perspectives of new radionuclides in Nuclear Medicine continue to evolve, driven by the development of isotopes with innovative applications in theragnostics.

In this second part of the continuing education series, the clinical and therapeutic applications of terbium, actinium, and bismuth are analyzed in depth. The use of the four terbium isotopes (terbium-149, terbium-152, terbium-155, and terbium-161) is described, offering a versatile system for both diagnosis and treatment due to their chemical similarity to lutetium-177, along with the challenges related to their production and availability. Additionally, actinium-225, a powerful alpha-emitting radionuclide, is reviewed for its growing role in Targeted Alpha Therapy (TAT), particularly in prostate cancer and neuroendocrine tumors. Finally, bismuth-213, derived from actinium-225, is analyzed for its short half-life, making it a viable option for localized and selective therapies.

Despite technical and production challenges, these radionuclides are driving the evolution of precision medicine, expanding therapeutic and diagnostic possibilities in Nuclear Medicine.

El estado del arte y las perspectivas futuras de los nuevos radionúclidos en Medicina Nuclear continúan evolucionando, impulsados por el desarrollo de isótopos con aplicaciones innovadoras en teragnosis.

En esta segunda entrega de la serie de formación continuada, se analizan en profundidad las aplicaciones clínicas y terapéuticas del terbio, actinio y bismuto. Se describe el uso de los cuatro isótopos del terbio (terbio-149, terbio-152, terbio-155 y terbio-161), que ofrecen un sistema versátil para diagnóstico y tratamiento gracias a su similitud química con el lutecio-177, junto con los retos en su producción y disponibilidad. Asimismo, se revisa el actinio-225, un potente emisor alfa con un papel creciente en la Terapia Alfa Dirigida (TAT), especialmente en cáncer de próstata y tumores neuroendocrinos. Finalmente, se analiza el bismuto-213, derivado del actinio-225, cuya vida media corta lo convierte en una opción viable para terapias localizadas y selectivas.

A pesar de los desafíos técnicos y de producción, estos radionúclidos están impulsando la evolución de la medicina de precisión, ampliando las posibilidades terapéuticas y diagnósticas en Medicina Nuclear.

The development of new radionuclides for theragnostic applications continues to expand the possibilities of Nuclear Medicine, improving both the diagnosis and the treatment of different pathologies.

After reviewing the first part of this series of continuing education articles on the theragnostic pairs copper-64/copper-67, lead-212/lead-203 and scandium-44/scandium-47, the second part of the series analyzes other emerging radionuclides with high clinical potential - terbium, actinium and bismuth.

These elements present physical and chemical characteristics that make them especially promising in targeted therapies and in molecular imaging. Here we describe their principle isotopes, methods of production, the advantages and challenges associated with their use and their growing integration into clinical trials and preclinical studies.

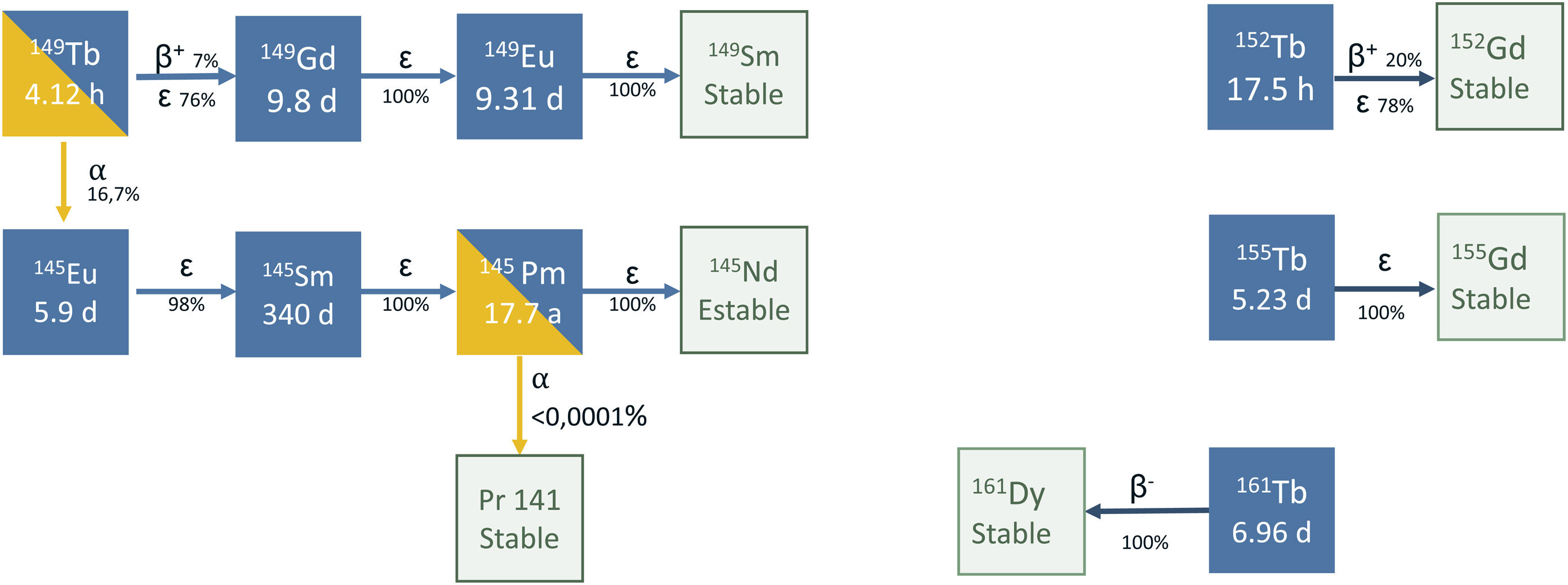

TerbiumTerbium presents four radioisotopes of interest for medical purposes: terbium-152 and terbium-155 for diagnosis, and terbium-149 and terbium-161 for therapy. These four radioisotopes are commonly referred to in the literature as the “terbium sisters”1 and allow the preparation of radiopharmaceuticals with different types of emission, but with identical pharmacokinetics (Fig. 1).

Terbium is a metal of the group of lanthanides with chemical properties similar to lutetium-177. This means that the same chelators used in the radiopharmaceuticals with lutetium-177 (DOTA, DOTATE, etc.) can be used, and therefore, they are available and widely studied.2–4

The availability of terbium isotopesThe production of these radioisotopes is not simple. The method most commonly used is spallation, which is a nuclear reaction in which a heavy nucleus is bombarded by a very high energy particle (of the order of gigaelectronvolts, GeV) so that the nucleus detaches or ejects a large number of free neutrons in response to the impact of the particle. This process is used to produce terbium-149, terbium-152 and terbium-155, by spallation reactions on a tantalum sheet in a high intensity proton accelerator. After the spallation process, the radioisotopes produced separate according to their mass-charge ratio. It should be noted that only a few centers around the world can produce these radionuclides (the ISOLDE and MEDICIS installations of the Conseil Européen pour la Recherche Nucléaire [CERN], or European Council for Nuclear Research and the national laboratory of Canada for nuclear physics and particles) and currently produce sufficient quantities for research. It is important to highlight that the limited number of installations that are operative today cannot fulfill the growing demand of terbium worldwide for healthcare practice.1 To meet this challenge, the possibility of constructing new installations that can expand production or examining possible new ways of production in commercial cyclotrons is under study.

The only isotope of this family that can be produced in a reactor is terbium-161, irradiating a gadolinium target highly enriched in gadolinium-160 with neutrons. The nuclear reaction used is 160Gd(n,c)161Gd and gadolinium-161 decays terbium-161 with a short half life = 3.7 min. Then, terbium-161 is isolated for medical use. The main problem that this method presents is the presence of impurities of terbium-159 which, although this is not a problem for the patient, it implies that all the radiopharmaceuticals produced with this radionuclide precursor will be an “added carrier” and thus, the specific activity of the radiopharmaceutical will be affected.

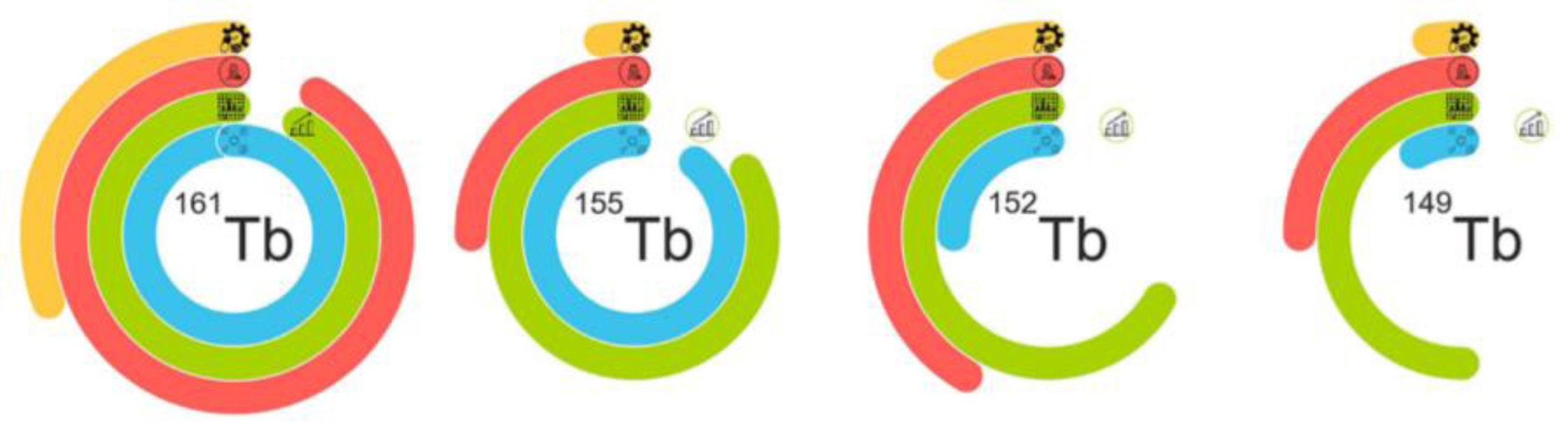

Fig. 2 shows the current status of the production of isotopes of this family.

Representation of the current status of the production of the radioisotopes of terbium. The four rings symbolize the four main phases of the implementation of radiopharmaceuticals: the blue color demonstrates the status of the production of the cyclotron/reactor; the green line represents the preparation of the separation process and includes problems with the ampliation process in the last curve; the red line shows the preclinical studies and the yellow line indicates the development of good manufacturing practices and clinical implementation. Image originally published in Frontiers in Nuclear Medicine: Moiseeva AN, Favaretto C, Talip Z, Grundler P V., van der Meulen NP. Terbium sisters: current development status and upscaling opportunities. Front Nucl Med. 2024;4(October):1–14.1

Terbium-149 has quite a complex decay scheme (Fig. 1), which combines the emission of α particles (reaching 25−28 μm in tissue), γ photons of energies that are well adapted for performing single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) (Eγ = 165 keV, Iγ = 26.4%), as well as β+ particles for positron emission tomography (PET) images.

This complex decay scheme is a limitation. Due to the possession of decay products that are radioisotopes with a long half-life: gadolinium-149 (t1/2 = 9.28 d), europium-145 (t1/2 = 5.93 d), samarium-145 (t1/2 = 340 d) and europium-149 (t1/2 = 93.1 d), among others, it is necessary to study in-depth the effect that they may generate in the organism. In their study on the efficacy of [149Tb][Tb(SCN-CHX-A-DTPA-rituximab)] for specifically killing individual circulating cancer cells or groups of small cells in vivo, Beyer et al.5 performed an extrapolation of this possible therapy at clinical doses, estimating a retention of residual activity after the injection of 1 GBq of the radiopharmaceutical and that the daughter radionuclides had a retention of 100% (the worse possible scenario), concluding that the activity retained after one year was of 100 kBq for europium-149, 41 kBq for samarium-145, and 2.2 kBq for prometrium-145. Despite remaining retained in the dose in the red bone marrow, they were under critical values.

From the point of view of pharmaceutical development, radiopharmaceuticals labeled with terbium-149 can be found in the first preclinical studies. Due to its chemical similarity with lutetium, one of the first lines of preclinical investigation is focused on comparing the therapeutic efficacy and safety of peptides targeted against the somatostatin receptor (SSTR) labeled with terbium-149 with the reference radiopharmaceutical. Mapanao et al.6 recently published a study with results showing the absence of hematotoxicity of the labeled compounds in a mouse tumor model after the administration of a dose of 40 MBq (activity much higher than the dose used in routine clinical practice with radiopharmaceuticals with an α emitting isotope).

Several focuses for the radiolabeling of fibroblast activation protein inhibitor molecules (FAPI) are also being explored, since the commonly rapid pharmacokinetics of the FAPI molecules coincide perfectly with the half-life of this radioisotope. The preliminary data on these compounds are very promising and preclinical studies on efficacy have been started in an in vitro model of sarcoma cells.7

Terbium-152Terbium-152 has a semidecay period of 17.5 h and decays gadolinium-152 by a competitive process of ®+ decays (probability of 17%) and electron captures (83%) and also has an α decay branch, but with a probability that is too low to be considered appreciable (7·10−7%). The most relevant ®+ decays have maximum energies of 2620 keV (5.9%) and 2970 keV (8%). In most transitions, terbium-152 decays at excited states of gadnolinium-152 (more than 200 possible levels) and thereafter produces γ emission. Of these emissions, only a few have relevant probability and energy of interest for medical applications (photons of 271 keV with a fraction of 8.6% and 344 keV with 65%).

This radionuclide is an adequate diagnostic tool for the dosimetry and monitoring of treatments with ligands labeled with terbium-149 and terbium-161. Given the multiple emissions of γ rays, it can be used in SPECT and the emission of positrons allows performing PET, although for PET, the emissions of γ rays can also represent a source of noise and an increase of the dose of radiation.

The first preclinical studies were carried out in 2019. All were performed as a proof of concept to determine the biodistribution and dosimetry of reference molecules such as DOTANOC,8 PMSA-6179 or the antibody fraction scFv78-Fc (tumor endothelial marker 1, TEM1).10 These studies were so promising that terbium-152 was the first of the four sisters for clinical application in a patient. Two studies in humans have been performed with two different molecules:

- 1

[152Tb][Tb(DOTATOC)] was administered to a 67-year-old patient with a well differentiated metastatic functional neuroendocrine neoplasm of the ileum who presented for restaging 8 years after the sixth cycle of peptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT).11 The PET images visualized even the smallest metastases with greater contrast between the tumor and the background over time. The relatively long half-life of terbium-152 made it feasible to scan the patient during a prolonged period, a characteristic that would be useful for dosimetric purposes before therapy with radionuclides based on radiolanthanides.

- 2

[152Tb][Tb(PMSA-617)] was administered to a 59-year-old patient with a refractory, little differentiated prostate adenocarcinoma, with a residual primary tumor that infiltrated both seminal vesicles, multiple lymph nodes and bone metastasis. The initial diagnosis was metastatic disease (stage IV) and a Gleason score of 8 (4 + 4). The patient presented for restaging of the whole body under androgen deprivation therapy to evaluate the possibility of performing therapy with [177Lu][Lu(PSMA-617)]. The PET studies were of diagnostic quality, with delayed images (18.5 and 25 h post-administration) being particularly relevant, allowing visualization of the same metastatic lesions and the local recurrent tumor detected previously by [68Ga][Ga(PSMA-11)].9

The production of this radionuclide is challenging and, thus, the possibility of its being available in the near future to cover clinical necessities is quite scarce. However, the clinical application of terbium-152 up to now, has paved the way for its transfer to clinical application.

Terbium-155Terbium-155 (t1/2 = 5.3 d) decays by electron capture at excited levels of gadolinium-155, which then produces an emission of γ photons mainly with an energy of 87 keV (32%) and 105 keV (25%), which allows it to be considered for use in SPECT.12 This application can be used for dosimetry calculation prior to treatment with its therapeutic pair terbium-161.13

SPECT images with Jaszczak type phantoms of sectors with terbium-155 and terbium-161 have shown excellent spatial resolution.14 The initial results indicate that the multiple photon emissions of both isotopes offer adaptability in the protocols of acquisition and reconstruction of images for optimizing their quality. Although the metrics of the limits of resolution, quantitative accuracy and optimal methods of image reconstruction still require more investigation, the fact that it is a γ emitter and presents this adaptability for optimizing image quality suggests that it may a successor to indium-111 in the evaluation of patients as candidates to receive therapy with radioisotopes such as yttrium-90, lutetium-177, holmium-166, ….. since chemically it is just as versatile.

Preclinical studies have been carried out with this radioisotope by the radiolabeling of small peptides such as DOTA-folate, an analog of minigastrin or DOTATOC and with an antibody targeting the L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1-CAM) in a mouse tumor model. The results showed that despite the low activity administered (8.5 MBq), the image quality was adequate for the absence of additional β+/β- emissions and the long half-life of terbium-155.15–17 This is a great advantage because it favors its use at low doses, thereby limiting the dosimetry of the patient. Another advantage is the fact that its production is being optimized in a commercial cyclotron, making large scale production more feasible and investigation would be simpler.18

Terbium-161This radionuclide (t1/2 = 6.9 d) decays by β–. It decays by nine different beta branches to the basal status or to an excited level of dysprosium-161, with excitation energies between 43 and 593 keV. These excited levels decay by emitting a great variety of conversion electrons, Auger and γ photons. This scheme provides advantages versus other β− emitter radioisotopes since it generates 2.24 electrons (conversion and Auger) for each β particle. This represents an elevated linear transfer of energy and a greater concentration of a short radiation dose path compared with electrons derived from β decay, and therefore, greater therapeutic efficacy, especially when the target is small sized (micrometastasis). In addition, by emitting photons (48.9 keV with a probability of 17% and 74.6 keV with a probability of 10.2%) images can be obtained for monitoring the distribution of the treatment.

The first preclinical studies were performed in 2013. Since then, most studies have compared the therapeutic capacity,19 radiotoxicity to the tumor,20 dosimetry,21–23 etc. of terbium-161 with respect to lutetium-177 (therapeutic radiometal of reference). In this sense, Müller et al.13 performed a preclinical study in a mouse model of prostate cancer comparing [161Tb][Tb(PSMA-617)] with the standard [177Lu][Lu(PSMA-617)]. The results indicated that the radiopharmaceutical labeled with terbium-161 had a 1.4-fold greater deposit of energy in established tumors compared with lutetium-177. This proportion increased up to approximately 4-fold for groups of small cells and individual cells. However, it may lead to doubts such as: Does this advantage represent an elevated dosimetry in radiosensitive organs such as the kidneys by renal elimination of the peptides that are radiolabeled?

In this regard the same group carried out a study in a model for comparing the renal dosimetry between [177Lu][Lu(folate)] and [161Tb][Tb(folate)]. The functional and histopathological analysis of the kidneys after the application of the radiopharmaceutical with terbium-161 revealed dose-dependent damage comparable to the damage caused by a radiopharmaceutical with lutetium-177 applied with the same activity. These observations are in line with the hypothesis that Auger electrons and electrons with low energy conversion do not produce additional renal damage, as previously observed during the therapeutic application of [111In][In(octreotide)] in patients.

The first study with this radioisotope in humans was performed in two patients in 2021. The first patient (35-year-old male with a well-differentiated and non-functional malignant metastatic paraganglioma) received a dose of 596 MBq of [161Tb][Tb(DOTATOC)] while the second patient (70-year-old male with functional tail of pancreas neuroendocrine neoplasm) received a dose of 1300 MBq of the same radiopharmaceutical. Both patients received different lines of therapy, one of which was [177Lu][Lu(DOTATOC)], and were recruited after showing progression in the follow-up PET study. Whole body planar scintigraphy images were acquired at different times for performing dosimetric calculations. This first study concluded that this radiopharmaceutical can be used for whole body planar images as well as for SPECT/CT images even with low activities.24

At present, there are three clinical trials with this radioisotope:

- ●

Beta-Plus (NCT05359146): Trial phase aimed at measuring the therapeutic index (proportions of dose between the tumor and the organ limiting the dose) of [161Tb][Tb(DOTA-LM3)] compared with the current standard [177Lu][Lu(DOTATOC)] in the same gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumor in a crossover and randomized design in all the patients.

- ●

Violet (NCT05521412): Phase 1–2 trial aimed at evaluating the safety and efficacy of [161Tb][Tb(PSMA-I&T)] in men with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer.25

- ●

Prognostics (NCT06343038): Phase 1 trial aimed at evaluating the safety and efficacy of the SibuDAB antibody targeting the PSMA receptor.

KEY POINT: Terbium presents four isotopes of clinical interest (149, 152, 155 and 161), which provide a versatile theragnostic arsenal with both diagnostic (SPECT/PET) and targeted therapy applications.

KEY POINT: The main challenge for the clinical application of terbium radioisotopes is their production, since spallation requires specialized installations and terbium-161 is the only one that is produced in a reactor, and therefore, presents limitations related to its purity.

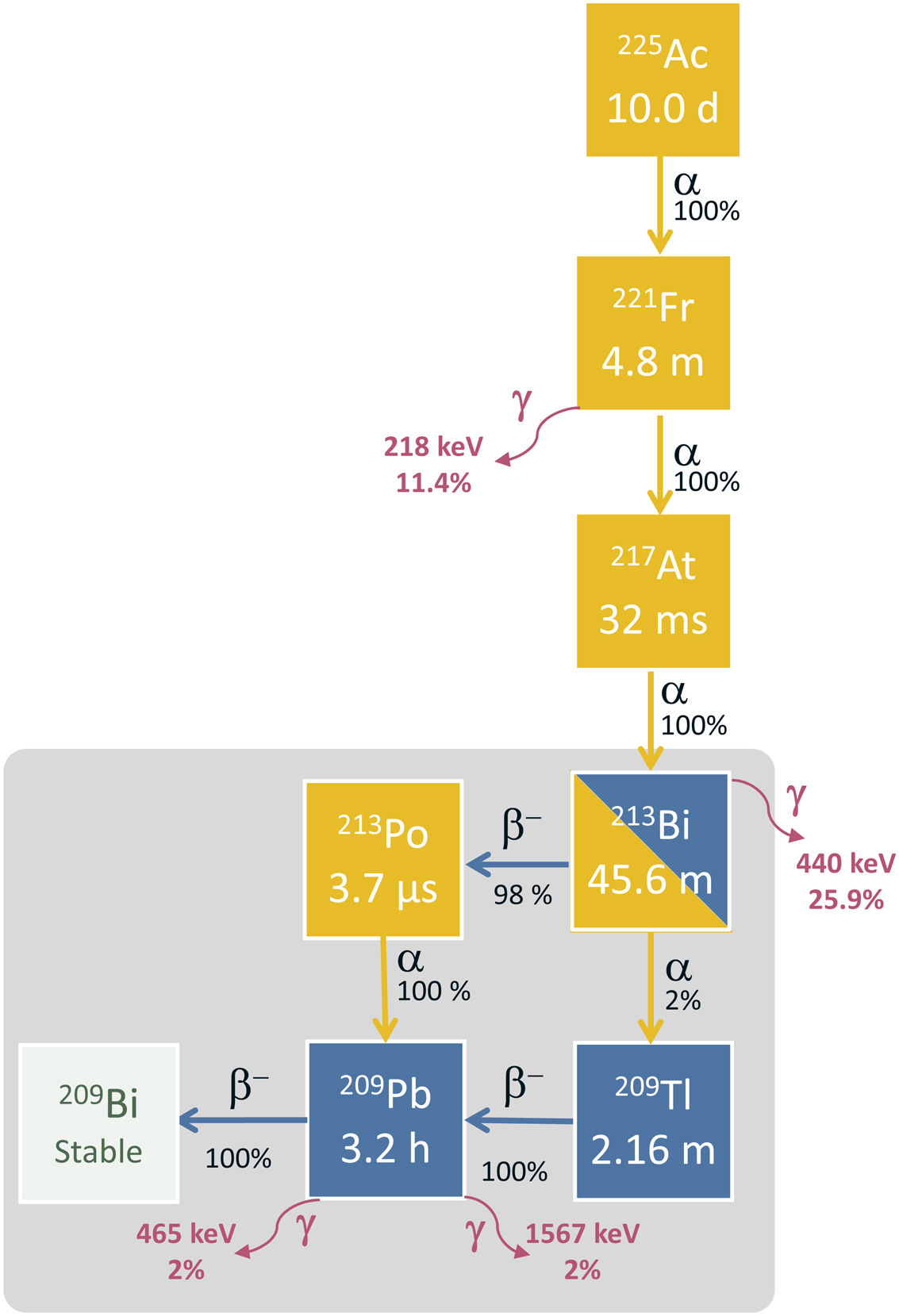

Actinium-225Physical characteristics and obtention processes of actiniium-225Actinium-225 has a semidecay period of 9.92 days and decays via a cascade of six radionuclides with a short half-life until reaching bismuth-209, which is considered stable (semidecay period of 2.01·1019 years). Through this cascade five α particles are emitted with energies ranging from 5 MeV to 8.4 MeV, reaching from 47 to 85 μm in tissue. The first three decays are almost all by α decay (francium-221, astate-217 and bismuth-213) with decay periods of 4.8 min, 32.6 ms and 45.6 min, respectively. From bismuth-213 up to bismuth-209, α and β decays are combined. This scheme is shown in Fig. 3. The following photons are emitted: 218 keV (11.4%) 440 keV (25.9%), 465 keV (1.9%) and 1567 keV (1.98%). These photons are useful for making images and quality control.26

Cambios realizados en el documento de power pointThe main source of actinium-225 is from the decay of thorium-229 (T1/2 = 7340 years). However, its availability is limited since no method for the obtention of this isotope has been developed, but rather it is extracted from the remains of nuclear tests obtained between the years 1954 and 1970 in Russia, Germany and the United States. This process of extraction and purification only allows obtaining around 1.7 Ci annually. In addition, the total quantity of uranium-233 is limited and more production is not expected due to non-proliferation agreements. This quantity is below the current needs for clinical trials and preclinical investigation.27 Thus, in the last decade there have been intensive searches for other means of production.

An alternative option for producing actinium-225 could be by the spallation reaction with high energy protons of natural thorium-232. Theoretically, a single irradiation of 10 days can produce comparable quantities to those obtained by the decay of thorium-229 at one year. The main limitation of this production pathway is that it needs protons with energies greater than 100 MeV and this is only available in a few installations in the world. There are two production strategies for increasing the availability of actinium-225. These two strategies are based on the irradiation of radium-226 with medium energy protons (15−20 MeV) and photons. At a theoretical level, irradiation with intermediate energy protons produces quantities comparable with the production by spallation reactions of thorium-232 and produces fewer impurities.28,29 However, the main advantage over the reaction of spallation and other production methods in the great availability of medium energy cyclotrons worldwide. When photons are used in the production, the quantity generated is lower and can be compensated by increasing the target mass, that produces the accumulation of radium-225, which can be used as a generator of actinium-225.30 To date, only initial experiments have demonstrated the viability of the use of these two strategies. The main challenges of these two forms of production is to ensure sufficient radium-226 and the development of technology for safe irradiation of highly radioactive targets.

The clinical images using actinium-225 also present challenges. Although the use of two energy peaks at 218 keV and 440 keV has been suggested for clinical imaging and recently a third peak at 78 keV in the spectrum of γ rays and actinium-225 has been identified, with a higher count,31,32 the low probability of γ emission and the superposition of Bremsstrahlung due to β emitters in the decay chain of actinium-225 hinder the obtention of images of sufficient quality for dosimetry in the clinical setting.33 Therefore, the current clinical investigation in targeted alpha therapy (TAT) is largely based on indirect approaches extrapolating radiopharmaceutical labeled with lutetium-177.33

Radiopharmaceuticals of actinium-225 and applicationsPeptide receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT) with isotope emitters of α, β radiation and Auger electrons is aimed at specific targets in the form of radiolabeled molecules and has revolutionized the treatment of cancer.34 Among the α emitters, actinium-225 is of note as one of the most promising radionuclides for PRRT. The advances in chelator technologies have facilitated its administration and stable internalization in the organism, improving its efficacy in clinical applications.

Most radiopharmaceuticals based on actinium-225 are composed by DOTA, a hydrophilic macrocyclic structure which, due to its characteristics, is the most stable chelator for the development of radiopharmaceuticals labeled with technetium-99m, gallium-68 and actinium-225.35–37

The radiopharmaceuticals containing actinium-225 with the most ongoing clinical trials are those targeting the PSMA and the SSRT for neuroendocrine tumors.

Radiopharmaceuticals for therapy in prostate cancerAmong the PSMA molecules most studied for therapy in prostate cancer with actinium-225 because of its high specificity and rapid pharmacokinetics are PSMA-617 and PSMA I&T.

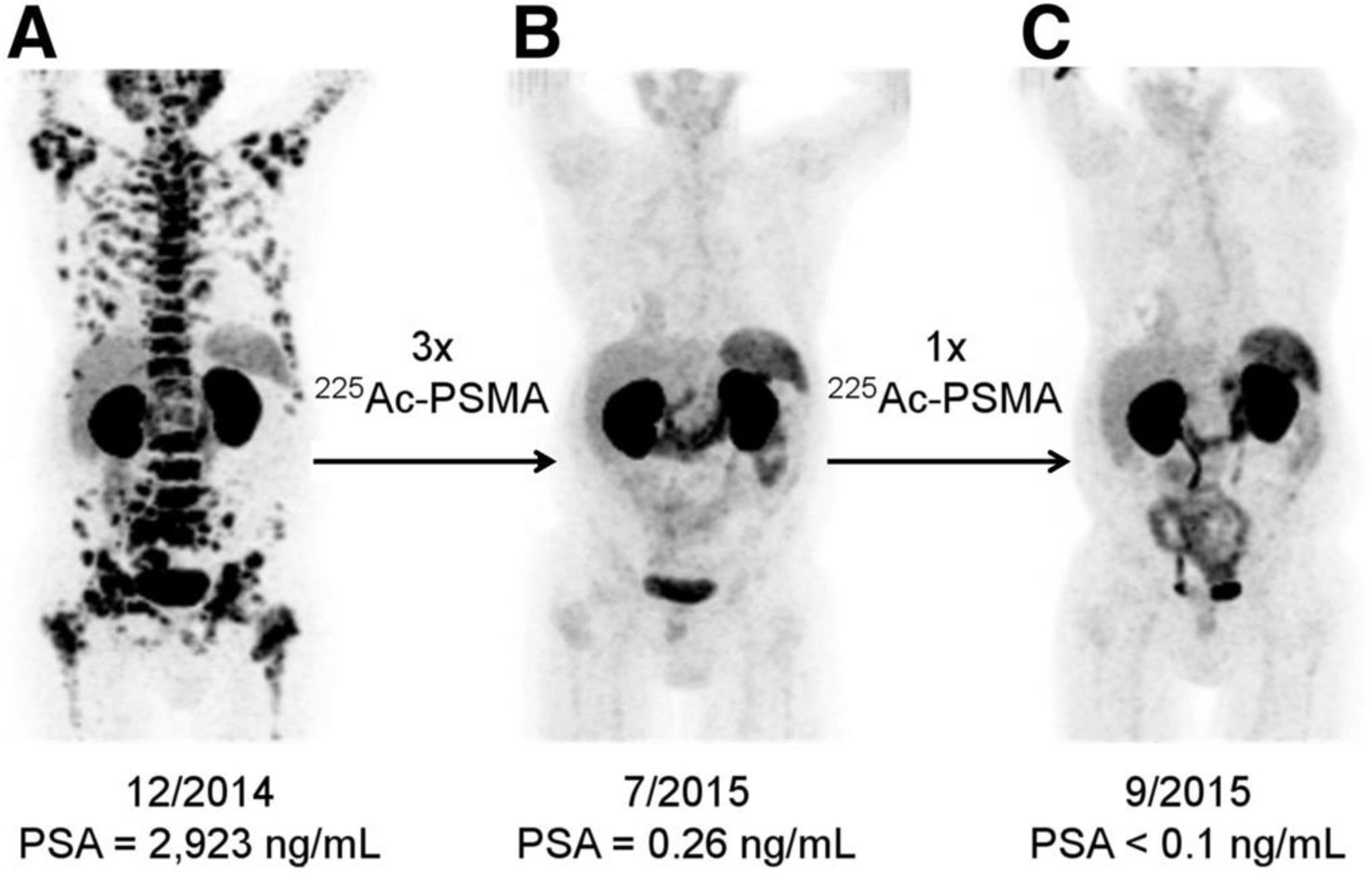

In 2021, Feuerecker et al.38 investigated the safety and activity of [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)] in 21 patients with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer after the failure of [177Lu][Lu(PSMA-617)]. Although the antitumoral activity of [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)] was significant, the non-specific uptake of the radiopharmaceutical in these glands led to irradiation of these glands, producing grade 1/2 xerostomy as an adverse effect in all the patients, requiring treatment discontinuation in 23%. It has been described that the prevalence of xerostomy in patients treated with [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)] increases with the number of cycles administered. Kratochwil et al.33 reported that the optimal activity of [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)] for inducing an antitumoral effect with tolerable adverse effects was 100 kBq/kg (Fig. 4). With this activity, the prevalence of grade 1 xerostomy was 100%. In contrast, in the patients treated with doses higher than 150 kBq/kg, 50% presented grade 2 xerostomy.

[68Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT of a patient treated with 4 cycles of [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)]. (A) Pre-therapeutic study. (B) Re-staging at two months of the 3rd cycle of [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)]. (C) Re-staging after two months of the 4th cycle. Image originally published in The Journal of Nuclear Medicine: C. Kratochwil et al., “225 Ac-PSMA-617 for PSMA-Targeted α-Radiation Therapy of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer,” J. Nucl. Med., vol. 57, no. 12, pp. 1941–1944, Dec. 2016. © SNMMI.41

A recent multicenter study including an elevated number of patients (n = 488) treated with 8 MBq of [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)] with a mean of 2 cycles (IQR: 2–4), reported the presence of xerostomy in 68% of the patients after the first cycle and in 100% of those who received more than 7 cycles. One of the possible factors contributing to the development of the effect is that approximately 1/3 of the patients previously received therapy with [177Lu][Lu(PSMA-617)]. Another known adverse effects of therapy with [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)], and which was reported in the same study, is possible bone marrow toxicity. The data obtained demonstrated anemia in 81% of the patients, thrombocytopenia in 54% and leukopenia in 44%, attributable, in part, to the low reserve of basal bone marrow due to previous treatments. The overall survival reported was 15.5 months and progression-free survival was 7.9 months.39

A phase 1 dose escalation clinical trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT04597411) aims to investigate the optimal dose for treatment with [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)] in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer with or without previous exposure to [177Lu][Lu(PSMA-617)].

With respect to the use of other PSMA molecules radiolabeled with actinium-225, such as PSMA I&T, the evidence is more limited given the small number of patients treated. Zacherl et al.40 reported the first clinical data with [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-I&T)] in 14 patients with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer, showing results that were highly comparable with those observed with [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)]. Two phase 2 and 2/3 clinical trials are currently in the recruiting stage to evaluate the effect of [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-I&T)] in patients with metastatic prostate cancer (ClinicalTrial.gov NCT06402331, NCT05219500).

Radiopharmaceuticals for therapy in neuroendocrine tumorsA defining characteristic of neuroendocrine tumors is the overexpression of SSRT. The SSRT analogs most frequently used as therapeutic agents are DOTATOC and DOTATATE radiolabeled with lutetium-177 or actinium-225.

The first therapeutic clinical study with [225Ac][Ac(DOTATOC)] in the treatment of neuroendocrine tumors was begun in 2011 by the group of Kratochwil et al.42 In 34 patients a maximum tolerable dose of 40 MBq was determined. In addition, it was found that the treatment was safe with a dose of 18.5 MBq every 2 months or 25 MBq every 4 months. Despite the response observed in several patients, the authors underlined the need for more studies with a better selection of patients and the optimum dose to administer.

In 2020, the first clinical study of the safety and efficacy of [225Ac][Ac(DOTATATE)] in 32 patients with neuroendocrine tumors with stable disease or in progression following complete treatment with [177Lu][Lu(DOTATATE)] was published. The treatment scheme used was: 2 cycles of 100 MBq/kg separated by 8 weeks; more cycles could be administered in the absence of disease progression in a PET/CT study with [68Ga][Ga(DOTATOC)]. The morphological response was evaluated in 24/32 patients, among whom 15 achieved partial remission and 9 remained stable. The levels of chromogranin significantly decreased following treatment and no disease progression or death was observed after a median follow-up of 8 months. In this study, most of the patients (41%) presented loss of appetite (grade II), followed by nausea and gastritis, particularly between 24 and 72 h after therapy with [225Ac][Ac(DOTATATE)], lasting an average time of one week in some patients.43

A phase 1 clinical trial (NCT06732505) is ongoing to evaluate the safety and efficacy of [225Ac][Ac(DOTATATE)] in patients with well-differentiated, inoperable, locally advanced, metastatic or progressive neuroendocrine tumors (G1/G2/G3) with or without a previous history of PRRT.

KEY POINT: Actinium-225 has revolutionized PRRT, but the toxicity and technical challenges limit its clinical expansion, requiring advances in production and dosimetry for satisfying the growing demand.

KEY POINT: Bone marrow toxicity and xerostomy during therapy with [225 Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)] increases with the number of cycles administered.

Bismuth-213Physical characteristics and processes of bismuth-213Bismuth-213 is the daughter radioactive isotope of actinium-225 as can be seen in Fig. 3. It decays by β− decay (98%) to polonium-213 and α (2%) decay to thallium-209 with a semidecay period of 45.6 min.44 These two radioisotopes decay into lead-209 via α emission (polonium-213) and β– emission (thallium-209). This finally decays through a process of β decay to the isotope bismuth-209. In this complex decay scheme both α particles and electrons of different energies are equally emitted as well as some γ photons that allow visualizing the distribution in images. In the decay via β− emission of bismuth-213 to polonium-213, the emission of maximum energy electrons of 982 keV (30%) and 1422 keV (66.8%) and the emission of a photon of 440 keV (25.9%) should be noted. Polonium-213 decays to lead-209 through α decay emitting a nucleus of helium with an energy of 8376 keV (100%) and with a semidecay period of 3.72 μs. Thus, 98% of the decays of bismuth finish emitting an α particle of 8376 keV. This particle has a mean free pathway in tissue of around 85 μm and may be considered as the most cytotoxic particle coming from the decay of bismuth-213. From the other arm of the decay of bismuth-213 to thallium-209 there is the emission of an α particle of 5785 keV (2%). Thallium-209 to lead-209 decays 100% via β− decay with a decay period of 2.2 min and a maximum energy of the β− particle of 1827 keV (97%). In this decay two high energy γ photons of 465 keV (95%) and 1567 keV (99%) are emitted. Finally, lead-209 decays via β− emission to bismuth-209 with a semidecay period of 3.2 h and a maximum energy of the β− particle of 644 keV (100%).

Bismuth-213 may be obtained with generators of 225Ac/213Bi and the radiopharmaceuticals can be prepared at the production site. The most established form of these generators is actinium-225 in acid solution and strongly retained by the solvent (i.e., AG MP-50, cation exchange resin). Bismuth-213 is eluted by a mixture of 0.1 M HCl/0.1 M NaI and [213Bi]BiI4 and [213Bi]BiI5 is obtained and can be used for radiochemical purposes.45 Thanks to the parent half-life of several days, these generators can be used clinically and allow long distance transportation. Among the parent and daughter radioisotope a transitory equilibrium is produced that allows elution every 3 h.46

Radiopharmaceuticals with bismuth-213 and applicationsChemical characteristicsThe oxidation state of bismuth in solution is Bi(III). In this state it forms complex structures in all the pH scale. This metallic ion presents an elevated affinity for ligands that contain oxygen and nitrogen donor atoms.

Radiopharmaceuticals that contain bismuth-213 present better results by combination with vector molecules with a short biological half-life; that is, small molecules, such as peptides or antibody fragments (including nanobodies), since their half-life is similar to that of the radioisotope, allowing bismuth-213 to deposit its energy before decaying.44

Among the chelators most commonly used for binding the radiometal to the vehicular molecule, diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) is of note, and has been widely used due to its speed of radiolabeling, but it presents limited stability in vivo. On the other hand, CHX-A”-DTPA, a structural modification of DTPA, presents greater stability. The stability of the complexes is critical since dissociation may result in renal toxicity by the accumulation of free bismuth-213. DOTA is considered the standard chelator due to its high thermodynamic stability but its use in radiolabeling is longer and requires heating conditions that may damage the vehicular molecule. The emerging chelators, such as NETA and DEPA, combine rapid kinetics of formation of complexes of acyclic systems with the stability of the macrocyclic systems, showing great potential for bismuth-213. Additionally, Me-DO2PA has shown to be stable in vivo when conjugated with bismuth-213.44

Preclinical studies with radiopharmaceuticals with bismuth-213Preclinical studies have explored a wide range of radiopharmaceuticals based on bismuth-213, using antibodies, antibody fragments, peptides and small molecules for different types of cancer.

- ●

[213Bi][Bi(DOTA-9E7.4mAb)] is an anti-CD138 monoclonal antibody that has been used in mice with multiple myeloma. The treatment based on α particles increased the median survival of the mice and showed cure rates in 45% of the cases. Better results were obtained than with the radiopharmaceutical labeled with lutetium-177 (β− particles).47

- ●

[213Bi][Bi(DTPA-2Rs15dsdAb)] is an antiHER2 nanobody that has been studied in a HER2pos tumoral model presenting peritoneal metastases. The radiopharmaceutical showed rapid accumulation in HER2+ tumors and prolonged the median survival in an animal model, especially in combination with trastuzumab.48

- ●

[213Bi][Bi(DOTATATE)] is a peptide with affinity to the SSTR, mainly type 2, and has been used in neuroendocrine tumors. A high efficacy was observed in comparison with β emitters, such as lutetium-177, as well as the need for lower doses for the destruction of tumoral cells.49

Preclinical studies have also been carried out with the use of radiopharmaceuticals labeled with bismuth-213 in other diseases such as pancreatic cancer ([213Bi]Bi-69−11 Ab, [213Bi][Bi(DTPA-C595-mAb)] and [213Bi][Bi(DTPA-PAI2-mAb)], colon cancer ([213Bi][Bi(IMP288-mAb)] and [213Bi][Bi(DTPA- A”-CHX-Bn-SCNuCC49ΔCH2)], breast cancer ([213Bi][Bi(DTPA-PAN-622-mAb)], [213Bi][Bi(DTPA-Cetuximab)] and [213Bi][Bi(DTPA-A”-CHX-Bn-7.16.4-mAb)], and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma ([213Bi][Bi(DTPA-anti-CD20-mAb)] and [213Bi][Bi(DOTA-biotin)].44

Clinical studies with radiopharmaceuticals with bismuth-213In clinical studies, radiopharmaceuticals have been used in both systemic and locoregional administration.

- -

[213Bi][Bi(CHX-A-DTPA-Lintuzumab)] (anti-CD33) has been used in patients with refractory or relapse of acute myeloid leukemia. When administered systemically, this radiopharmaceutical has demonstrated to be safe and shows antitumoral activity in phase I and II studies, especially in combination with cytarabine. Six clinical responses were observed in patients with characteristics of low risk who received a dose of ≥37 MBq/kg.50

- -

[213Bi][Bi(DOTATOC)] has been studied in patients with advanced neuroendocrine tumors and resistant to β emitters such as yttrium-90 and lutetium-177. The treatment was administered intraarterially in 7 patients and systemically in 1 patient. Prolonged antitumoral response was obtained, with complete remission in one case.51

- -

[213Bi][Bi(PSMA-617)] has been investigated in a patient with metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer refractory to conventional treatments. Two cycles of the radiopharmaceutical were administered with an accumulated dose of 592 MBq, obtaining a notable reduction in PSA levels and excellent molecular response in the PET/CT study with [68Ga][Ga(PSMA-11)].52

- -

[213Bi][Bi(anti-EGFR)] has been used in patients with in situ bladder cancer refractory to Bacillus Calmette-Guérin treatment. A pilot study was designed to evaluated the viability, tolerability and efficacy of the radiopharmaceutical administered by intravesical instillations (1 or 2 doses of 366−821 MBq). Complete remissions were observed at 8 weeks in one third of the patients treated, some of whom remained disease-free for more than three years.53

- -

[213Bi][Bi(DOTA-Substance P)] has been evaluated in patients with grade II to IV gliomas. The administration of up to 14.1 GBq with a maximum of 8 cycles with 2 month intervals was performed intratumorally or in surgical cavities through implanted catheters. The median survival from the initiation of treatment was 7.5 months. However, several patients achieved complete remission with the absence of recurrence up to 23.8 months after finalizing treatment.54,55

- -

[213Bi][Bi(DTPA-9.2.27mAb)] (AIC) was designed for the treatment of melanoma with expression of the melanoma-associated chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan antigen. The administration was initially by intralesional injection with variable doses based on size. Extensive tumoral necrosis was observed, with preservation of the surrounding tissues and with no significant adverse hematological effects.56 This radiopharmaceutical was later used systemically in metastatic melanomas, obtaining 50% of stable disease, 14% of partial response and 6% of complete response. No significant toxicities were described.57

KEY POINT: Radiopharmaceuticals with bismuth-213 present better results by combination with vector molecule with a short biological half-life, overall with peptides and antibody fragments.

KEY POINT: 98% of the decays of bismuth-213 finish with the emission of high energy α particles (8376 keV) reaching only 85 µm in tissue, thereby maximizing tumoral destruction with minimum damage to healthy tissue.

Conclusions and future perspectivesThe development and application of new radionuclides in Nuclear Medicine continue advancing rapidly, offering innovative solutions within the setting of diagnosis and personalized therapy. This review describes an in depth analysis of the clinical potential of terbium, actinium and bismuth, highlighting their physicochemical properties, their principle therapeutic applications and the challenges associated with their production and availability.

Terbium, with its four isotopes of interest, represents a versatile option in theragnosis, although its production by spallation continues to be a barrier for large scale clinical implementation. Actinium-225 has become consolidated as a potent α emitter for targeted alpha therapy, with promising results in prostate cancer and neuroendocrine tumors, although its limited production still restricts access to this radiopharmaceutical. In regard to bismuth-213, its short half-life and capacity for highly localized treatments makes it a valuable tool in specific applications, although its dependence on generators of actinium-225 poses logistic challenges.

As production strategies become optimized and the clinical evidence is expanded, these radionuclides have the potential to transform the panorama of Nuclear Medicine. In future articles, we will discuss other emerging radionuclides and their impact on the development of new therapeutic and imaging strategies, with the aim of continuing to explore the future of precision medicine.

None.

![[68Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT of a patient treated with 4 cycles of [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)]. (A) Pre-therapeutic study. (B) Re-staging at two months of the 3rd cycle of [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)]. (C) Re-staging after two months of the 4th cycle. Image originally published in The Journal of Nuclear Medicine: C. Kratochwil et al., “225 Ac-PSMA-617 for PSMA-Targeted α-Radiation Therapy of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer,” J. Nucl. Med., vol. 57, no. 12, pp. 1941–1944, Dec. 2016. © SNMMI.41 [68Ga]Ga-PSMA-11 PET/CT of a patient treated with 4 cycles of [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)]. (A) Pre-therapeutic study. (B) Re-staging at two months of the 3rd cycle of [225Ac][Ac(PSMA-617)]. (C) Re-staging after two months of the 4th cycle. Image originally published in The Journal of Nuclear Medicine: C. Kratochwil et al., “225 Ac-PSMA-617 for PSMA-Targeted α-Radiation Therapy of Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer,” J. Nucl. Med., vol. 57, no. 12, pp. 1941–1944, Dec. 2016. © SNMMI.41](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/22538089/0000004400000003/v3_202509170456/S2253808925000308/v3_202509170456/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr4.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)