Microscopic colitis is a colonic chronic inflammatory disease that encompasses two histological subtypes: collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis.1 Despite of its unknown etiology, several risk factors have been associated (such as drugs [see Table 1]) that may produce intestinal immune dysregulation. Microscopic colitis presents mainly as non-bloody watery chronic diarrhea, most of complementary test are non-specific and its diagnosis is histological through biopsies.2 For this reason it is an underdiagnosed disease.3 Oral corticosteroid therapy with budesonide is preferred treatment and clinical remission is the main treatment goal. Progressive descending dose pattern is used however, a maintenance dose is sometimes required due to high recurrence risk.4

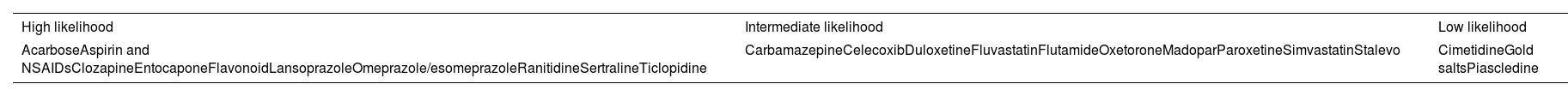

Drugs triggering microscopic colitis.

| High likelihood | Intermediate likelihood | Low likelihood |

|---|---|---|

| AcarboseAspirin and NSAIDsClozapineEntocaponeFlavonoidLansoprazoleOmeprazole/esomeprazoleRanitidineSertralineTiclopidine | CarbamazepineCelecoxibDuloxetineFluvastatinFlutamideOxetoroneMadoparParoxetineSimvastatinStalevo | CimetidineGold saltsPiascledine |

We were presented with an 87-year-old woman allergic to phenoxymethylpenicillin with a medical history of arterial hypertension, G3b chronic kidney disease, trigeminal neuralgia, and asymptomatic chronic hyperuricemia. She was undergoing treatment with irbesartan–hydrochlorothiazide 150–12.5mg/24h, carbamazepine 200mg/12h (started two months ago) and allopurinol 100mg/24h (for years). She had a good baseline psychofunctional situation (Barthel Index 100, Lawton and Brody scale 6/8, Reisberg Global Deterioration Scale 1), was a widow, had two children and lived alone.

She reported 7–8 unrelated to ingestion daily watery stools (ocher stools, sometimes explosive, frequently nocturnal), fecal incontinence episodes, intense meteorism and general syndrome for a month and a half. In this context, she suffered two syncopes with associated falls (one with pain and functional impotence in the right upper limb) and a progressive eczematous rash on trunk, face, neck, upper limbs and thighs which were being treated with corticosteroids. In the systematic physical examination, we noted: afebrile, sustained tensions, anodyne abdomen, previously mentioned skin lesions and inflammation signs with joint range limitation in the right shoulder. The most remarkable blood test findings were: creatinine 1.51, potassium 3.4, cortisol 1.8, adrenocorticotropic hormone 8.43, complete blood count, liver function and acute phase reactants in normal ranges. Simple radiographs of the chest, abdominal and right shoulder did not reveal any significant alteration.

During admission, excepting calprotectin (137μg/g), stool studies (stool culture, Clostridium difficile toxin, parasites, occult blood test), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and IgA antithyroglobulin antibodies with IgA determination were negatives. Abdominal-pelvic CT revealed a 25mm long segment with concentric wall thickening in distal transverse colon however no neoplasia signs were found. A subsequent colonoscopy revealed a sigmoid colon peridiverticular colitis suggestive pattern and biopsies were taken. Despite dietary changes and some drugs suspensions, diarrhea persisted. Histological analysis confirmed a colonic mucosa lymphocytic colitis pattern. After starting oral budesonide (9mg/24h), stool patterns and general condition improved.

Furthermore, eczema improved after topical corticosteroid therapy and oral antihistamine (biopsy showed non-specific eczema), hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis suppression (due to previous exogenous corticosteroids intake) was corrected after a hydroaltesone regimen and acute renal failure as well as hydroelectrolytic alterations were solved thanks to fluid therapy. Additionally, we diagnosed a right supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons complete rupture and right scapular partial rupture, and a conservative management approach was taken.

There are only 6 cases of lymphocytic colitis due to carbamazepine published in scientific literature: first in a pediatric patient in 19975; another in a 77-year-old man 6 months after drug onset intake6; third was a 54-year-old man 6 weeks after starting carbamazepine intake7; two cases in a retrospective cohort of 199 patients in which colitis remitted after corticosteroid treatment8; and the last one published was a 77-year-old man who had received radiotherapy due to colorectal cancer 2 months after starting the drug.9

In the described case clinical manifestations persisted despite several pharmacological adjustments and after having ruled out neoplastic etiology. Furthermore, symptoms had begun one month after carbamazepine intake. Although carbamazepine could explain skin signs, skin reactions after months of allopurinol intake have been reported, even with no dose changes. This case emphasizes the importance of taking a detailed medical history as well as geriatric syndromes (functional deterioration, falls, polypharmacy), which often present as negative health events after morbid stressors. In alignment with previous studies, the patient presented a good response to corticosteroids. However, recurrence remains possible during dose reduction.

Microscopic colitis should be taken into account when making the differential diagnosis of elderly chronic diarrhea (even when accompanied by general syndrome) due to its high prevalence and increasing incidence, its quality of life impact and the effective therapeutic options availability.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.