Local antibiotic delivery is crucial in prosthetic infections due to the limited bone penetration of systemic treatments. With the rise of bacterial resistance, alternatives are being explored to utilize these antibiotics without compromising their properties. The aim of this study is to investigate the application of stereolithography in manufacturing customized objects that incorporate thermolabile antibiotics and analyze their biomechanical behavior.

Materials and methodsA stereolithography (SLA) 3D printer with biocompatible resin Optoprint® Lumina was used to create different models, incorporating various amounts of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid. Mechanical studies were conducted to evaluate the performance of the 3D-printed models before and after antibiotic release.

ResultsResin pieces without antibiotics demonstrated higher resistance, while adding the antibiotic reduced resistance by 18%, and after the elution of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, the reduction reached 56% of their total strength. Comparatively, antibiotic-loaded cement pieces retained more than twice the resistance post-elution. The progressive loss of biomechanical strength correlated with the antibiotic release from the resin pieces.

ConclusionsThe results of this study suggest that it is feasible to design pieces with variable structural characteristics using SLA (stereolithography) printing with biocompatible resin, combined with the incorporation of drugs, including thermolabile antibiotics.

La liberación local de antibióticos es crucial en infecciones protésicas debido a la limitada penetración ósea de los tratamientos sistémicos. Con el aumento de resistencias bacterianas, se buscan alternativas que permitan emplear estos antibióticos sin afectar sus propiedades. El objetivo de este estudio fue explorar la aplicación de la estereolitografía en la fabricación de objetos personalizados que incorporan antibióticos termolábiles y su comportamiento biomecánico.

Material y métodosSe empleó una impresora 3D de estereolitografía (SLA) con resina biocompatible Optoprint® Lumina y se crearon diferentes modelos a los que se les añadían diferentes cantidades de amoxicilina-clavulánico. Se realizaron estudios mecánicos para evaluar el comportamiento de los modelos impresos en 3D previo y tras la liberación de antibiótico.

ResultadosLas piezas de resina sin antibiótico mostraron mayor resistencia, mientras que la adición del antibiótico redujo la resistencia en un 18%, y tras la elución de la amoxicilina-clavulánico, la reducción alcanzó el 56% de su resistencia total. En comparación, las piezas de cemento con antibiótico mantuvieron más del doble de resistencia tras la elución. La pérdida progresiva de la resistencia biomecánica se correspondía con la liberación del antibiótico de las piezas de resina.

ConclusionesLos resultados de este estudio sugieren que es posible diseñar piezas con características estructurales variables mediante la impresión SLA (esterolitografía) utilizando resina biocompatible, combinada con la incorporación de fármacos, incluidos antibióticos termolábiles.

Prosthetic surgery has been defined as the 20th century surgery. The 21st century surgery will be prosthetic replacement. The aging population, along with a social shift towards a more active population with greater functional demands, has led to a progressive increase in prosthetic surgery worldwide. The main complication of this surgery is prosthetic infection, both in terms of frequency and its impact on the quality of life of the affected patient.

In the treatment of prosthetic infections, the local release of antibiotics is a fundamental element, due to the particular bone penetration of systemic drugs. Currently, in the field of medicine, bone cement (polymethyl methacrylate [PMMA]) continues to be used to address therapeutic situations such as the creation of spacers for osteoarticular infections,1–3 as structural support in bone defects with the addition of antibiotics,4 or through its use in surgical revisions to provide stability to implants, such as prostheses.5,6 However, due to the polymerisation properties of cement, not all antibiotics can be used. Thermolabile antibiotics are relegated to a secondary role because of the alteration of their physicochemical properties, thus reducing their antimicrobial capacity against infections.7–9 Therefore, and given the current increase in bacterial resistance, it is necessary to find alternatives to broaden the spectrum of antibiotic use that are not affected by cement polymerisation and that also offer optimal mechanical resistance.10–143D printing has revolutionised not only the ability to manufacture new healthcare products but also the development of materials for this type of manufacturing. Currently, there are resins designed for 3D printing that polymerise when exposed to ultraviolet light. These resins have the advantage of not requiring heat for polymerisation. Furthermore, they have a high capacity to incorporate other substances into their composition, such as minerals or other active ingredients. Creating implants using this technique would allow the addition of heat-labile antibiotics, such as beta-lactams, to their composition, enabling the local release of antibiotics over a controllable period.13–17

The aim of this study is to design parts for 3D printing using SLA (stereolithography) with biocompatible resin and an antibiotic (amoxicillin–clavulanic acid), providing structural support and allowing for drug elution over time, while also analysing their mechanical strength.

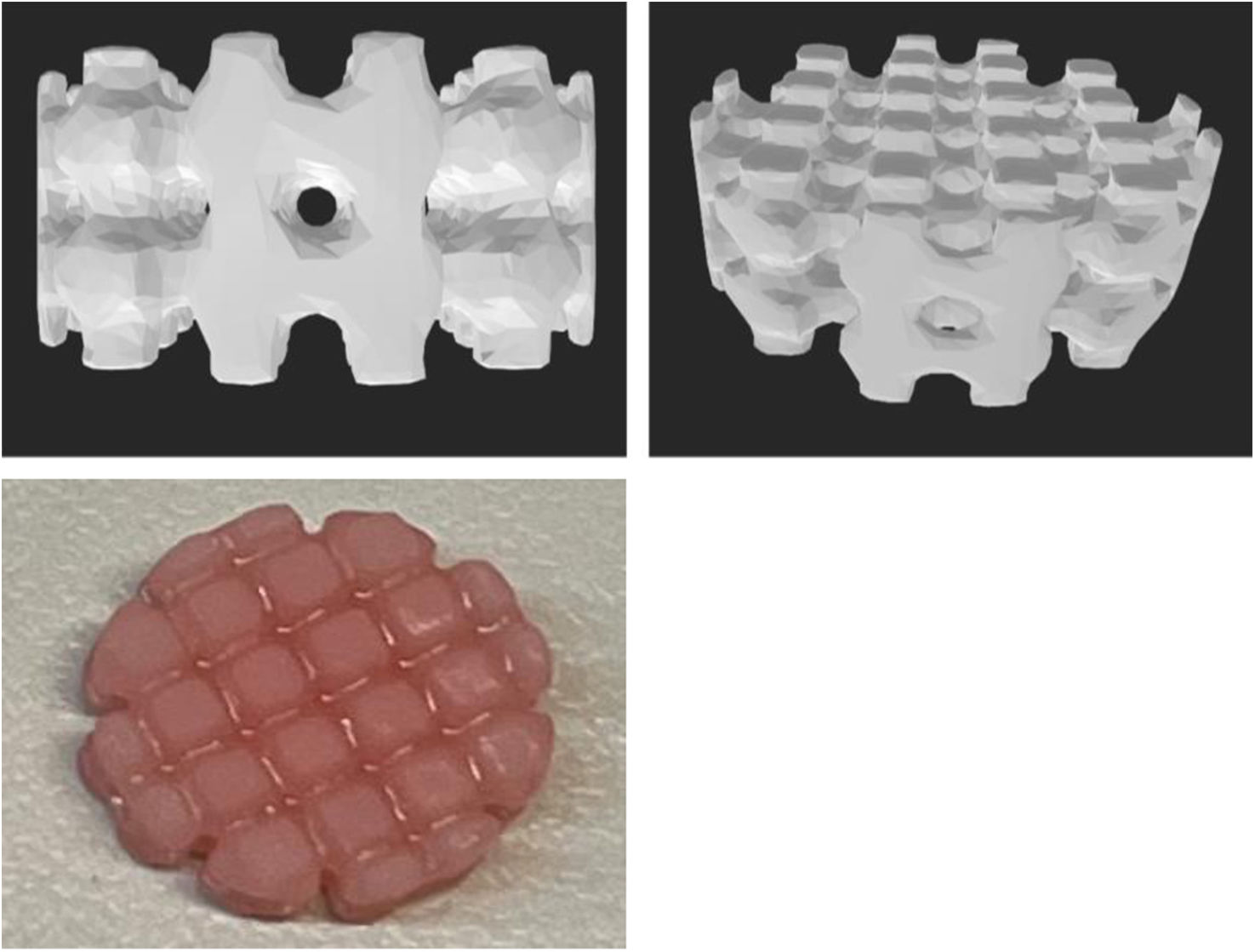

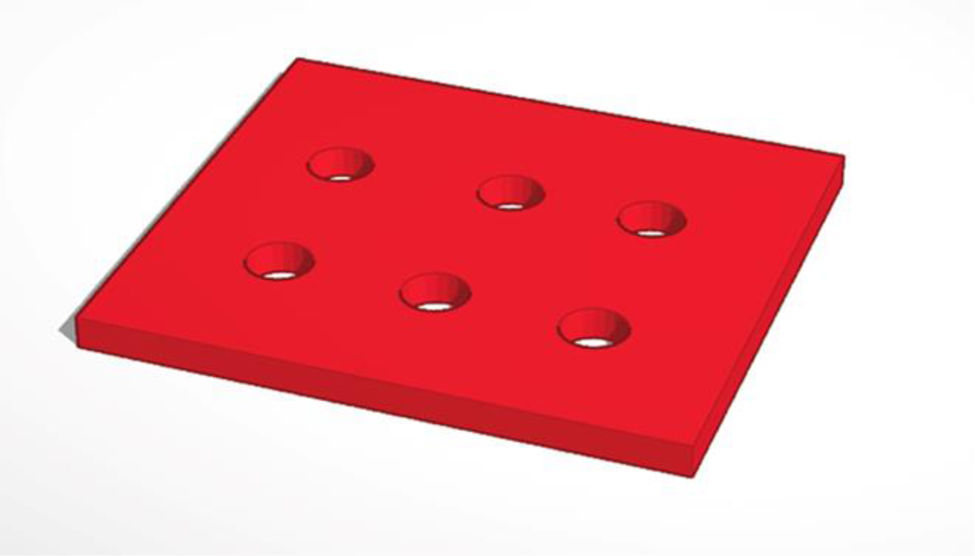

Material and methodsAn in vitro experimental study was conducted prospectively from 2021 to 2023. For the various studies, cylindrical pieces 10mm in diameter and 5mm in height (Fig. 1) with 1mm diameter holes spaced every 2mm were designed using Meshmixer® software.

For the fabrication of the pieces via 3D printing (model A), Optiprint® Lumina 500mg/400ml resin (Dentona) was used due to its biocompatibility and approval for human use. This methacrylate-based resin is suitable for photopolymerisable 3D printing and works with printers that use light in the 385–405nm range.

For the antibiotic selection, amoxicillin–clavulanic acid was chosen because it is a broad-spectrum antibiotic used in multiple infections, but it is heat-sensitive and therefore not used with bone cement. Its use was chosen to expand the currently available therapeutic options. To 10g of resin, 100mg of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid was added, mixed with a glass rod, and allowed to stand for 5min. After this time, the homogeneity of the mixture was checked. The process was repeated, and it was confirmed that homogeneous mixtures suitable for 3D printing were obtained.

To prepare the 3D printed parts, 10g of Optiprint® Lumina resin were weighed on an ABJ 220-4NM® precision balance (Kern). Amoxicillin–clavulanic acid (Normon® 2000/200mg powder for solution for infusion) was then added to the specimens. Five groups of specimens were generated: without antibiotic, with 1g, with 1.5g, and with 2g of antibiotic, and with 2g of antibiotic eluted after 7 days. It was decided to start with 1g and 1.5g to assess the behaviour of the released specimens, as well as 2g because these are the doses commonly used in patients. The printer used was the Elegoo Mars 2®, a stereolithography (SLA) model that employs the bottom-up printing method.

For the creation of the cement specimens (model B) used in the comparative study, Palacos® LV cement (Haraeus) was used. The cement pieces were manufactured using standardised procedures, following ISO 5833 and the instructions of the Palacos® LV cement manufacturer. Briefly, 40g of the solid component, the amount typically found in cement packages, were mixed with 2g of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid powder using the geometric dilution method to obtain a homogeneous mixture. Based on a pre-designed model, a Creality Ender-3® 3D printer was used to create a polylactic acid (PLA) mould, which allowed for the production of cylindrical cement pieces 10mm in diameter and 10mm in height. In this case, the resulting pieces were solid and did not contain any internal cylindrical holes (Fig. 2).

After obtaining the 3D-printed parts, the compressive force required to break the resin parts was measured. Parts printed solely with resin served as a control to determine the breaking strength of the polymerised Optiprint® Lumina resin, which was compared to the breaking strength of cement parts containing 2g of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid.

Therefore, three groups of resin parts were evaluated:

- 1.

A group in which the resin parts did not contain the antibiotic.

- 2.

A group in which the parts were analysed before antibiotic elution, to observe how the presence of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid affected the resin's hardness.

- 3.

Another group in which the parts were studied after 7 days of elution, in order to determine the resistance after antibiotic release.

The breaking strength of specimens from model A (resin) before and after elution was compared with that of specimens from model B (cement with 2g of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid).

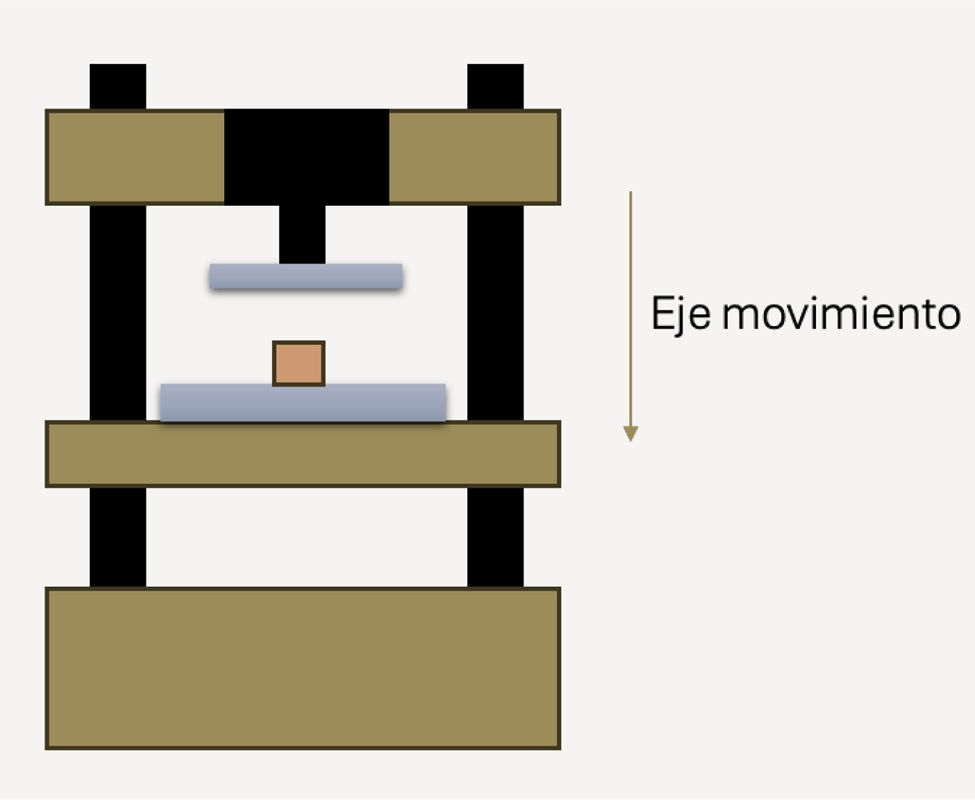

To determine mechanical strength, each specimen was placed on the lower carriage of the PCE-MTS500® motorised testing machine (PCE Instruments) (Fig. 3). The applied force was monitored using the PDE-DFG N 5K dynamometer (PCE Instruments), which measures compressive force from 0 to 5000N with an accuracy of .1%. The testing machine could apply forces up to 5000N, with a carriage feed speed ranging from 30mm/min to 230mm/min.

Each specimen was subjected to compression in the testing machine to determine its breaking strength. The data obtained were recorded and stored on the computer and subsequently processed using Microsoft® Excel to generate graphs showing the applied compressive force as a function of time until the pieces broke.

Data and statistical analysisThe data obtained are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean. A Student's t-test was used to determine the differences in means between two groups. The number of pieces required for printing was determined statistically. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Bonferroni correction was used to determine the differences between three groups. In all cases, a p-value less than .05 (p<.05) was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software Inc.).

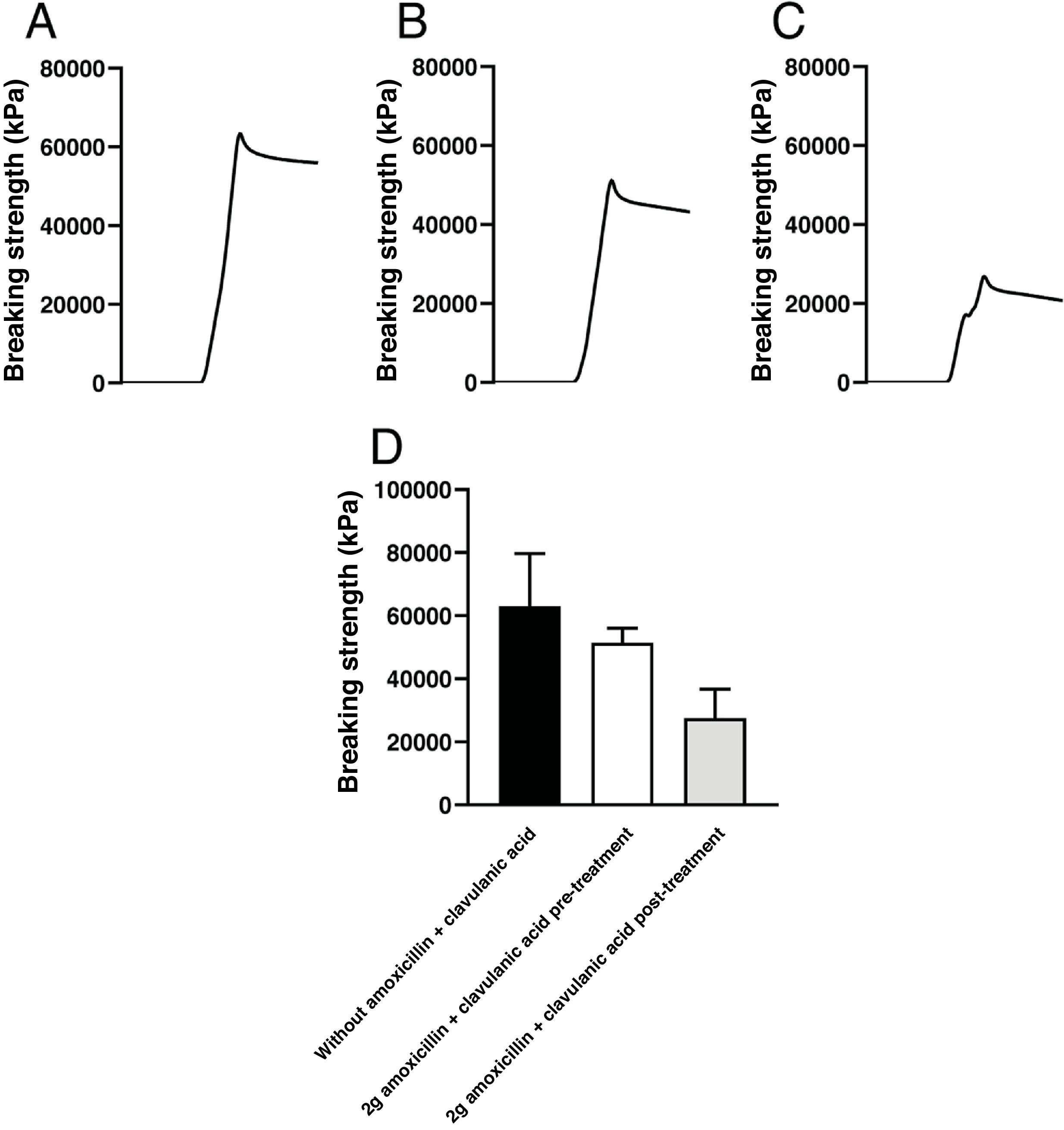

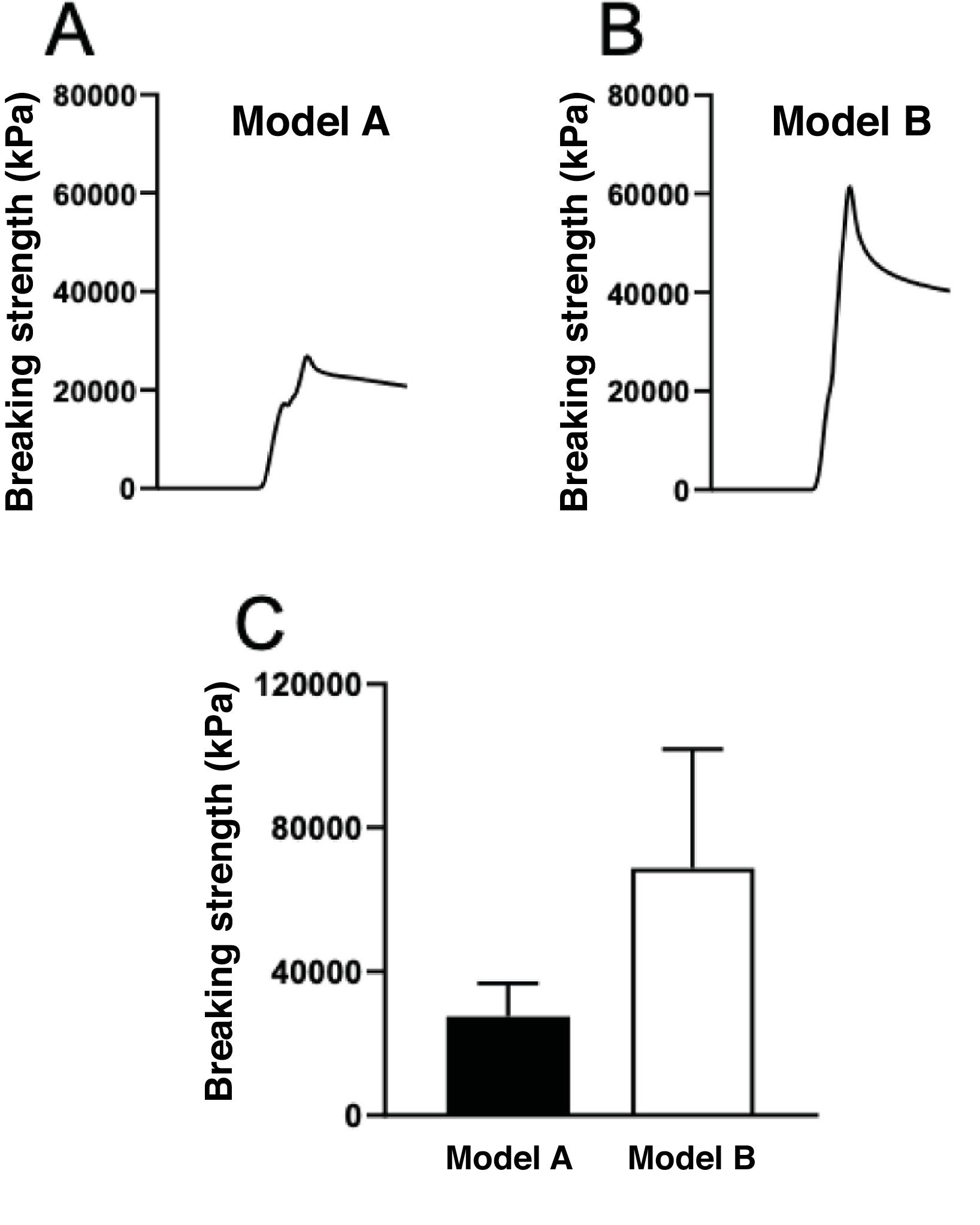

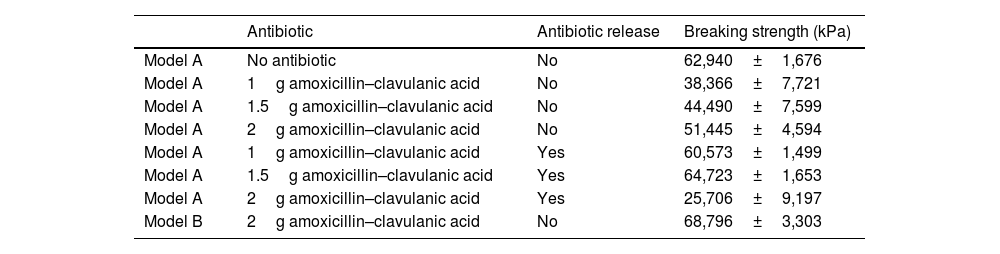

ResultsThe results obtained for each of the pieces after being subjected to the PDE-DFG N 5K dynamometer to determine the breaking force was, for the pieces of model A without antibiotic, an average value of 62,940±1,676kPa. In the resin-printed parts mixed with the antibiotic, the mean values obtained were 38,366±7,721kPa with 1g of antibiotic (without release), 44,490±7,599kPa with 1.5g of antibiotic (without release), and 51,445±4,594kPa with 2g of antibiotic mixed with the resin (without release) (Fig. 4).

Records of the compressive force applied until breakage of the pieces of model A, printed with 10g of Optiprint® Lumina resin, (A) in the absence (without Amox+Clav) or in the presence of 2g of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid; (B) before (2g Amox+Clav pre) and (C) after (2g Amox+Clav post) of drug elution. (D) Mean values and standard deviation of the breaking strength of the pieces of model A under the different experimental conditions.

In the case of the resin-antibiotic pieces in which antibiotic release had occurred, the following results were obtained: for resin matrices with 1g of antibiotic, 60,573±1,499kPa; for resin matrices with 1.5g, 64,723±1,653kPa; and for resin matrices with 2g, 25,706±9,197kPa (Table 1).

Summary of the matrices used biomechanically, whether or not they contained antibiotics, and comparison with cement.

| Antibiotic | Antibiotic release | Breaking strength (kPa) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model A | No antibiotic | No | 62,940±1,676 |

| Model A | 1g amoxicillin–clavulanic acid | No | 38,366±7,721 |

| Model A | 1.5g amoxicillin–clavulanic acid | No | 44,490±7,599 |

| Model A | 2g amoxicillin–clavulanic acid | No | 51,445±4,594 |

| Model A | 1g amoxicillin–clavulanic acid | Yes | 60,573±1,499 |

| Model A | 1.5g amoxicillin–clavulanic acid | Yes | 64,723±1,653 |

| Model A | 2g amoxicillin–clavulanic acid | Yes | 25,706±9,197 |

| Model B | 2g amoxicillin–clavulanic acid | No | 68,796±3,303 |

Model A, with 2g of released antibiotic in its mix, exhibited a resistance of 25,706kPa, significantly lower than the 51,445kPa of the resin matrix mixed with 2g of antibiotic that had not been released, and higher than the 68,796kPa of model B (a cement-based piece) with 2g of antibiotic in its mix.

Model A pieces, printed solely with Optiprint® Lumina resin without antibiotic, showed greater fracture resistance than those to which 2g of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid was added. The addition of this antibiotic reduced the fracture strength by 18%. Furthermore, after elution of the antibiotic for 7 days, the pieces showed an additional reduction in resistance, reaching a 56% decrease compared to the pieces without antibiotic.

The breaking strength of model A pieces after elution of the antibiotic (2g post) was compared with model B pieces, made of cement mixed with 2g of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid. The compressive force required to break model B (made with cement) was more than double that required to break model A (made of resin) (Fig. 5). The piece made with cement and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid exhibited greater hardness than the piece printed with Optiprint® Lumina resin. Model B (made with cement) showed significantly greater resistance to breakage even after drug elution, with differences in mechanical strength in terms of hardness and comparative strength (Fig. 6).

Record of the compressive strength developed until breakage of: (A) a piece of model A (resin) and (B) a piece of model B (cement) fabricated with 2g of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid after drug elution for 7 days. (C) Mean breaking strength values of the pieces of model A and model B fabricated with 2g of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid after drug elution for 7 days.

Currently, although bone PMMA remains the most widely used material as a local antibiotic carrier for the treatment of infections, it requires a high temperature for polymerisation, thus limiting the use of certain types of antibiotics.18 Biomechanically, sterilisation by gamma or beta radiation also influences the cement's properties, as it reduces the polymer's molecular weight, unlike ethylene oxide, which does not affect this molecular weight.19 Therefore, despite the cement's optimal strength, there is a significant limitation when using it as a local antibiotic carrier.20,21

In our study, we observed that the model A pieces printed solely with resin, without antibiotic, exhibited a mean tensile strength of 62,000kPa, coinciding with values previously described in the literature.22 On the other hand, the model pieces containing 2g of antibiotic showed a mean value of 51,445kPa. After antibiotic elution, this model's tensile strength decreased to 25,706kPa.

Regarding cement, the literature extensively describes the tensile strength of PMMA, which can reach up to 75,000kPa.22,23 This value is close to that observed in our study, in which the PMMA pieces achieved an average tensile strength of 69,000kPa. Compared to cement, the decrease in strength of model A demonstrates that removing the antibiotic from the structure makes the piece more brittle and considerably reduces its fracture resistance, but it still maintains optimal values for use in patients. The mechanical properties of the pieces with resin and antibiotic, before elution, are similar to those of the pieces printed with resin only.22,24

Although mechanical tests showed that model A (made with resin) had lower resistance after antibiotic elution compared to those pieces that had not eluted the drug, this decrease is explained by the release of the antibiotic, which makes the pieces less resistant to breakage compared to those made with cement. In cement, there is practically no release of the antibiotic from within due to the alteration of the physicochemical properties of amoxicillin–clavulanic acid. One of the major advantages of the resin used in our study is that, because the pieces are printed using SLA technology, they preserve the physicochemical properties of antibiotics like amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, which are thermolabile. This expands the possibilities of its application in clinical practice, thus increasing the available therapeutic arsenal. Even so, the printed values were higher than those described in the literature for tensile forces with maximum values of 47,000kPa, being lower than the values obtained in this study of model A (resin) with the antibiotic not released.25

Compared to other materials used in 3D printing, PLA filament (also called polylactic acid) is a key component, and it is also used in extrusion printers. Mechanical variability in extrusion printing is among the highest, reaching approximately 50%, in contrast to SLA printing, whose variability is only 1%.24 Objects manufactured using SLA printing have been documented to withstand tensile forces of up to 66,000kPa, while those generated with extrusion technology26 reach only 33,000kPa. Tensile strength increases with increasing layer thickness, as fractures typically originate at the junction between layers, where polymerisation occurs. Thanks to low anisotropy and efficient interlayer polymerisation, parts obtained with SLA exhibit greater tensile strength compared to those manufactured using extrusion printers.

Although a cylindrical design with perforations was used to facilitate in vitro study and testing, for clinical application, the antibiotic-resin mixture could be used with moulds or structures as needed or desired for patients. 3D printing allows for the creation of custom-made objects depending on the needs of both the surgeon and the patient, enabling a much more personalised clinical practice. This means that pieces such as plates or screws could be designed for implantation within the patient, providing structural support and delivering antibiotics for prophylaxis or treatment of osteoarticular infections.

Among the limitations of this study is its in vitro experimental nature and the fact that, for clinical applicability, animal experimentation would be required for preclinical validation prior to a clinical trial. Furthermore, the current literature on this topic is limited.

ConclusionsSLA printing allows for the production of prostheses using biocompatible resin containing amoxicillin–clavulanic acid, a heat-labile antibiotic that currently cannot be used in bone cement due to the alteration of its physicochemical properties caused by polymerization. Although its mechanical strength is lower compared to bone cement, it is optimal for future use in patients.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

FundingThis project received the 2022 SECOT RESEARCH grant.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.