The SCAE-SM (Request for an Appointment in Specialized Care-Suspicion of Malignancy) computer application is a tool available to Primary Care physicians for the referral of patients who should be evaluated by the specialist in a maximum period of 2 weeks when malignancy is suspected. The objective of our work was to analyze the usefulness of this tool and propose areas for improvement in the management of patients with suspected musculoskeletal malignancy.

Material and methodsA descriptive cross-sectional study of 235 referrals received in the years 2012–2017 was carried out. Their origin, the information contained in the applications and the response provided by historical evaluators, without specific oncology training, were analyzed. For this study, a new blind assessment of all applications was carried out by 13 orthopedists with different levels of specific training in musculoskeletal oncology (re-evaluators).

ResultsAmong all SCAE-SM, only 8.23% of patients had aggressive benign or malignant disease. The most successful re-evaluators in the adequacy of early appointment were those with moderate oncological training (5–10 years of experience). During the study, of all the patients treated in the Tumor Unit, only 18.81% accessed through the SCAE-SM circuit, with a mean waiting time of 18.11 days from the PC referral.

ConclusionsThe SCAE-SM computer application as tool for improve the management and advance care for patients with malignant musculoskeletal tumor pathology is useful, although the use of the circuit is inadequate. It is necessary to disseminate and generalize it, as well as to implement basic oncology training programs both in the field of Primary Care and Hospital.

La aplicación informática Solicitud de Cita en Atención Especializada-Sospecha de Malignidad (SCAE-SM) es una herramienta informática de la que disponen los médicos de atención primaria (AP) para la derivación de pacientes que deban ser valorados por el especialista en un plazo máximo de 2 semanas, cuando se sospeche de una enfermedad maligna. El objetivo de nuestro trabajo fue analizar la utilidad de esta herramienta, y proponer áreas de mejora en la gestión de los pacientes con sospecha de malignidad musculoesquelética.

Material y métodosSe realizó un estudio descriptivo transversal de las 235 derivaciones recibidas en los años 2012-2017. Se analizó su procedencia, la información contenida en las solicitudes y la respuesta proporcionada por evaluadores históricos (facultativos traumatólogos sin formación específica oncológica). Para este estudio se ha realizado una nueva valoración ciega de todas las solicitudes por 13 traumatólogos con distinto nivel de formación específica en oncología musculoesquelética (re-evaluadores).

ResultadosDe entre todas las SCAE-SM, solo el 8,23% de los pacientes presentaron enfermedad maligna o benigna agresiva. Los re-evaluadores más acertados en la adecuación del adelanto de cita fueron aquellos con formación oncológica moderada (5-10 años de experiencia). Durante el periodo de tiempo del estudio, de todos los pacientes tratados en la unidad de tumores, solo el 18,81% accedieron por el circuito SCAE-SM, transcurriendo un tiempo medio de espera de 18,11 días desde la derivación de AP.

ConclusionesLa aplicación informática SCAE-SM como herramienta de gestión y adelanto de la asistencia a los pacientes con enfermedad tumoral musculoesquelética maligna es útil, si bien el uso del circuito es inadecuado. Es necesario difundirlo y generalizarlo, así como implementar programas de formación oncológica básica tanto en el ámbito de la AP como de la hospitalaria.

A musculoskeletal tumour is a localised mass in bone or soft tissue caused by uncontrolled growth of cells derived from mesenchymal tissues. Malignant forms include metastases and primitive malignant tumours (primary malignant bone tumours, soft tissue sarcomas and haematological neoplasms).

Primary musculoskeletal tumours are rare and are classified into soft tissue sarcomas (1% of all cancers and responsible for 2% of deaths from the disease, with a mortality rate in Spain of 3391 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants/year) and soft tissue sarcomas (1% of all cancers and responsible for 2% of deaths from the disease, with a mortality rate in Spain of 3391 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants/year) and in malignant bone tumours (which represent .18% of all cancers, causing .21% of deaths, with a national mortality rate of .675 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants/year).1,2 Although these tumours are rare, bone metastases from other primary malignant tumours are the most frequent malignant bone lesions. Prostate and breast cancer are the primary malignant tumours that most frequently produce bone metastases, with an incidence of up to 68% and 60%, respectively. Other cancers that also commonly metastasise to bone tissue include lung, kidney, and thyroid cancers.3

Aggressive benign musculoskeletal tumours, such as giant cell tumours, osteoblastomas, aneurysmal bone cysts or deep fibromatosis, have continuous local growth that requires treatment and, in most cases, surgical resection.4–6

The suspected diagnosis of a musculoskeletal tumour is based on clinical and imaging data, although these are non-specific and can easily be confused with other diseases.1 As alarm symptoms7 that should trigger the physician's clinical suspicion, it has been reported that all soft tissue tumours should be studied, with special importance given to tumours of a size greater than or equal to 5cm in diameter, and those that increase in size and/or are deep to the fascia, even if they are not painful, should also be studied.1,7 In the case of bone tumours, the main symptom that should trigger diagnostic suspicion is the presence of deep, persistent bone pain with inflammatory characteristics, whether or not associated with a palpable tumour.1,7 The lack of specificity of the symptoms and signs of the disease, together with its low incidence in the general population, means that delays in diagnosis are common, and can be attributed to the patient (when they delay consulting), to the primary care physician or to the health system itself.1,8 When clinical suspicion of malignancy is aroused, patients should be referred to a centre that specialises in the diagnosis and treatment of this type of tumour, preferentially and through specific referral routes.

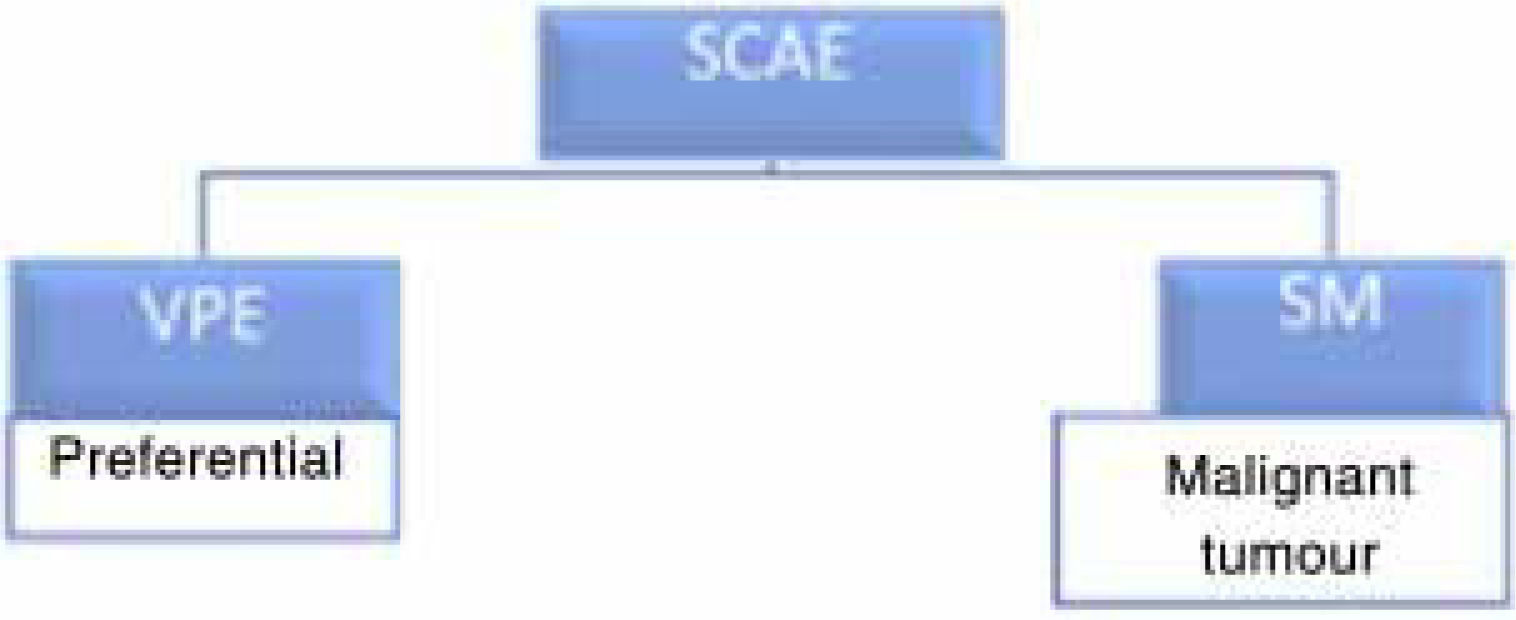

In the autonomous community of Madrid there is a computerised tool for providing early specialised medical care for patients with suspected malignant musculoskeletal tumours called “Request for an Appointment in Specialised Care – Suspected Malignancy” (SCAE-SM). This tool was devised as a healthcare pathway for the early identification of patients suspected to have malignant tumour disease and to bring forward their treatment, an objective common to all clinical practice guidelines on the subject.1,9,10 In fact, diagnostic delay of more than 6 months is associated with a worsening prognosis for patients in terms of overall survival and the development of metastases.11 The SCAE tool is a rapid referral pathway from primary care with two possible referral routes: one for patients requiring “preferential specialist assessment” (VPE) and one for those with suspected malignancy (SM) (Fig. 1). When this SM route is activated and the hospital specialist considers the request for an early appointment appropriate, the first specialist consultation must take place within no more than 15 days.12

The aim of our study was to analyse the usefulness of the SCAE-SM computer application based on the hypothesis that a healthcare pathway for identifying patients with suspected malignant musculoskeletal tumours accelerates diagnosis of the disease and its treatment, but requires a flow of information, permanent communication, and adequate specific training of all the professionals involved.

Material and methodStudy designA cross-sectional descriptive observational study was conducted to analyse the SCAE-SM tool results. Cases with suspected musculoskeletal tumours that were referred using the tool were patients with suspected bone metastases, haematological diseases with bone involvement (myeloma and lymphoma), aggressive benign bone or soft tissue tumours, soft tissue sarcomas and primary malignant bone tumours.

All referral requests were assessed and answered at the time by different traumatologists from the department with no specific training in musculoskeletal oncology, referred to “historical assessors”. At the time of the study, a new blind assessment of the total requests was performed by 13 traumatologists from different hospitals in Spain, who were selected based on their specific training in musculoskeletal oncology. The specific training levels considered were advanced (>10 years of experience, 2 traumatologists), moderate (5–10 years of experience, 6 traumatologists), and low (<5 years of experience, 5 traumatologists).

Obtaining the informationIn line with the ethical standards of the research procedures, the information was obtained by a review of the referral requests, which recorded the clinical and/or radiological reason described by the primary care physician, along with their work centre and professional data. The medical records of the referred patients and the complementary imaging tests performed were also reviewed.

Study populationPatients from the health area of our hospital (450,681 inhabitants), referred to the musculoskeletal tumour unit (UTME) of the orthopaedic surgery and traumatology department through the SCAE-SM pathway for suspected malignant or benign aggressive musculoskeletal tumour from 2012 to 2017. Out of a total of 235 requests, one was excluded because it was duplicated and three because the patients were lost to follow-up. The final study sample was 231 applications, which were divided into 2 groups: patients with aggressive malignant or benign disease (group A) and patients with benign non-aggressive or non-tumour disease (group B).

Over the same period, 82 additional patients who did not come via the SCAE-SM route were attended in the department's UTME because they presented with malignant or benign aggressive tumour disease of both bone and soft tissue. These patients constituted group C.

Management and analysis of the data and variables studiedThe requests made from primary care and the response issued by the hospital specialist (historical assessor and re-assessors) were analysed in relation to the quality of the information provided and the appropriateness of the referral as SM, based on symptoms and/or alarm signs (Table 1). We also studied the pre-hospital delay and the time to starting specific treatment for group A patients.

Criteria for the adequacy of the information provided and the suspicion of malignancy.

| Sufficient information | Adequate suspicion of malignancy | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | In bone lesions:The presence or otherwise of pain and its characteristics (mechanical or inflammatory pain) is reported and there is an X-ray in orthogonal projections (although findings are not described) or a radiologist's report suggesting or not ruling out malignancyIn soft tissue lesions:Presence of a lump and its size is reported (ultrasound is not necessary) or there is a radiologist's report suggesting or not ruling out malignancy | In bone lesions:Refractory inflammatory pain in appropriate epidemiological context (personal history of cancer). X-ray with aggressiveness: poorly defined lysis, cortical rupture, discontinuous periosteal reaction, or soft tissue invasionRadiologist's report suggesting or not ruling out malignancyIn soft tissue lesions:Deep lump greater than approximately 5cm in diameter or superficial lump that “has grown”. Radiologist's report suggesting or not ruling out malignancy |

| No | In bone lesions:No pain reportedType of pain not reported. There is no X-ray in 2 projections (only one projection)There is no imaging test and no radiologist's reportIn soft tissue lesions:The size of the lump is not reported. There is no imaging test or radiologist's report | In bone lesions:There is no inflammatory pain. No radiographic signs of aggressiveness and no radiologist's report suggesting or ruling out aggressivenessIn soft tissue lesions:There is no deep lump larger than 5cm or superficial lump that has grown. There are no radiographic signs of aggressiveness and no radiologist's report suggesting or ruling it out |

X-ray: plain X-ray.

The interobserver reliability of the SCAE-SM tool was determined by comparing the answers given by the 13 re-assessors to study the degree of concordance between them by means of the strength of concordance obtained with Cohen's kappa index, according to which, depending on the kappa value obtained, the strength of concordance was poor, weak, moderate, good, or very good.

Statistical studyAll data were collected and annotated by the principal author of the study on a form from which they were entered into a database in Microsoft Access 2000 for storage and management.

A descriptive analysis was performed by calculating the frequency distribution for qualitative variables. For quantitative variables, the mean, standard deviation, maximum and minimum values, median and interquartile range were calculated, according to their adjustment to normal distribution. The fit of the data to normal distribution was checked using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. The degree of concordance for the different groups of assessors was determined using Cohen's kappa index for 2 or more than 2 observers, as appropriate.

The data were analysed using SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Epidat, epidemiological data analysis software, was used to assess the degree of inter-observer concordance. Version 4.2. Consellería de Sanidade, Xunta de Galicia, Spain; Pan American Health Organization (PAHO-WHO); Universidad CES, Colombia. In all cases a significance level α=.05 was used.

ResultsDescriptive results from the sample groupsOf the 231 cases analysed, 19 (8.23%) were classified into group A and 212 (91.77%) in group B. In addition, 82 patients with malignant musculoskeletal disease, who we designated as group C, accessed the SCAE-SM tool through different referral routes. Table 2 shows the mean age and gender distribution of the patients analysed in the total sample and in each of the groups studied.

Summary of the epidemiological data of the cases in the series.

| Total sample (n=231) | Malignancy (group A) (n=19) | No malignancy (group B) (n=212) | Malignancy another route (group C) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Mean | 54.94 | 57.63 | 54.69 | 49.11 |

| SD | 20.23 | 18.40 | 20.41 | 19.21 |

| Median | 55.00 | 63.00 | 54.00 | 47.00 |

| IQR | 42.00–72.00 | 47.00–72.00 | 41.25–71.00 | 40.32–70.00 |

| Range | 1–98 | 20–86 | 1–98 | 8–91 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 111 (48.05%) | 9 (47.37%) | 102 (48.11%) | 35 (43%) |

| Female | 120 (51.95%) | 10 (52.63%) | 110 (51.89%) | 47 (57%) |

SD: standard deviation; n: number of cases; IQR: interquartile range.

The final diagnosis to classify patients into one group or another was reached by anatomopathological study after a biopsy or by combined clinical, analytical, and imaging data, ratified by the current review of the clinical history, which was performed in all cases.

The 19 patients in group A were diagnosed by biopsy on 16 occasions and by combined clinical, analytical, and imaging data in the remaining 3 patients (2 metastases and 1 well-differentiated liposarcoma). They included 8 soft tissue sarcomas, 6 primitive malignant bone tumours, 3 bone metastases and 2 aggressive benign tumours (one giant cell bone tumour and one case of aggressive fibromatosis). The most frequent soft tissue sarcoma was liposarcoma, present in 4 patients. The histological subtypes of these liposarcomas were 3 myxoid and 1 dedifferentiated. The median time from the referral request by the primary care physician to the first consultation at the UTME was 18.11 days and 52.63% of the patients were seen in under 14 days. The median time from this first consultation until initiating the corresponding treatment (medical or surgical) was 27 days. Details of the cases are summarised in Table 3.

Table summarising the cases in group A (malignancies).

| Case | Diagnosis | Sex age | Delay in 1st consultation in UTME from PC (days) | Start of treatment from 1st consultation in UTME | Treatment | Oncological result (follow-up: years+months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Multiple myeloma | ♀64 | 12a | 105 | Observation | DF (3y+2m) |

| 2 | Multiple myeloma | ♀75 | 36 | 180 | CT | No response (4 years) |

| 3 | Ewing's S. of pelvis. Stage III | ♂20 | 4 | 18 | CT+RT+CT | MTS (5y+8m) |

| 4 | Prox. humerus chondrosarcoma Stage IA | ♀48 | 25 | 270 | Surgery | DF (5y+2m) |

| 5 | Epithelioid angiosarcoma. Stage IIB | ♂78 | 5a | 55 | RT | Exitus (7 years) |

| 6 | Distal femur leiomyosarcoma. Stage IIB | ♂47 | 18 | 49 | CT+surgery+RT | MTS (4y+8m) |

| 7 | Vertebral metastases. Lung Ca | ♂86 | 4a | 1 | Palliative | Exitus (1 month) |

| 8 | Clavicular MTS. Prostate Ca | ♂72 | 0a | 1 | Palliative | Exitus (2 months) |

| 9 | Proximal humerus MTS. Endometrial Ca | ♀68 | 100a | 7 | RT | Exitus |

| 10 | Giant cell tumour of the distal femur. Stage 3 | ♂60 | 16 | 16 | Surgery | Recurrence+MTS (5y+7m) |

| 11 | Myxoid liposarcoma of the thigh. Stage IB | ♀32 | 5 | 16 | Surgery | DF (5y+1m) |

| 12 | Myxoid liposarcoma of the thigh. Stage IB | ♂42 | 10 | 15 | Surgery+CT+RT | DF (3y+5m) |

| 13 | Dedifferentiated LS of the thigh. Stage IIIB | ♀66 | 5 | 112b | Surgery | ? |

| 14 | Myxoid liposarcoma of the leg. Stage IA | ♀49 | 16 | 55 | Surgery+RT | DF (1y+6m) |

| 15 | Pleomorphic sarcoma of the arm | ♂66 | 3a | 3b | CT+RT | ? |

| 16 | Pleomorphic sarcoma of the thigh. Stage IV | ♂72 | 32 | 27 | Surgery+RT | Recurrence MTS (5 years) |

| 17 | leiomyosarcoma of the leg. Stage IIA | ♀73 | 28 | 20 | Surgery | DF (1y+4m) |

| 18 | Extraskeletal Ewing's sarcoma of the shoulder. Stage IIB | ♀25 | 18 | 51 | CT+RT+CT | DF (1y+11m) |

| 19 | Fibromatosis/periscapular desmoid tumour | ♀55 | 7a | 253 | Surgery+RT | Rest (3a+6m) |

Ca: carcinoma; CT: chemotherapy; DF: disease free; LS: liposarcoma; MTS: metastasis; PC: primary care; RT: radiotherapy; S: sarcoma; UTME: musculoskeletal tumour unit.

Regarding the primary care physicians and workplaces from which the request for care was issued, there were no statistically significant differences in the number of requests or the proportion of cases between group A and group B of the sample.

Descriptive results from the historical assessorThe results on the decisions taken by the historical assessor regarding the adequacy of the information sent by the primary care physician and the referral are summarised in Table 4. Despite the lack of information in almost 20% of the requests (6 patients in group A and 40 in group B), we conclude correct performance in early appointments for patients with malignant disease and in rejecting those with benign disease which was statistically significant (p<.001).

Results of concordance between re-assessorsWhen analysing the strength of agreement between the 13 re-assessors regarding the decision for early appointments for patients, it was found that the highest percentage of correct decisions for early appointments for patients in whom malignant disease was confirmed was obtained by specialists with intermediate specific training, while the re-assessors with advanced specific training had more success in not giving early appointments to patients with benign disease (Table 5).

List of successes between re-assessors with different degrees of specific training in early appointments for patients in groups A and B.

| Advanced | Intermediate | Low | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early appointment A | 68.42% (47.37–89.47%) | 85.96% (73.68–100%) | 74.74% (15.79–94.74%) |

| No early appointment B | 75.47% (63.68–87.26%) | 69.73% (59.43–82.08%) | 72.08% (56.60–94.34%) |

In the series of patients overall, the strength of concordance between the re-assessors with different specific training was considered moderate both in estimating the adequacy of the information provided by the primary care physician and in the origin of the early appointment. The highest values were found in the group of assessors with intermediate training compared to those with low training and, above all, to those with advanced training. In the latter, concordance was weak in all the parameters analysed (Table 6).

Kappa index between assessors in the assessment of sufficient, adequate, and appropriate information and the origin of the early appointment, according to the specific training of the assessors. Total sample of the patients in the series (n=231).

| Specific training of the assessors | Sufficient information (95% CI) | Adequate informationKappa (95% CI) | Early appointmentKappa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced | .279 (.154–.403) | .357 (.253–.461) | .384 (.278–.491) |

| Intermediate | .384 (.323–.445) | .539 (.473–.604) | .519 (.456–.582) |

| Low | .196 (.126–.267) | .578 (.512–.645) | .304 (.241–.365) |

| Total | .292 (.245–.338) | .523 (.468–.579) | .437 (.389–.486) |

Values considered acceptable are in bold.

Rapid and specific referral routes for patients with suspected malignant musculoskeletal disease are essential for their early diagnosis and treatment. The aim of this work is to study the functioning of the current pathway, the SCAE-SM tool, in the autonomous community of Madrid, to identify requests for early appointments for patients with malignant musculoskeletal tumours or aggressive benign tumours.

It is estimated that a primary care physician with a practice that sees approximately 3000 patients per year would see at least 3 patients with benign soft tissue tumours annually and one patient with soft tissue sarcoma every 24 years.13 Malignant bone tumours are even less frequent, with an estimated incidence 3–4 times lower than that of soft tissue sarcomas.14 This epidemiological fact and the insidious and non-specific nature of the symptoms mean a potential delay in diagnosis.1,8

The diagnostic delay that is considered significant is difficult to quantify. The delay attributed to the health system suggests the need to implement specific referral routes for patients with this disease, to shorten the waiting time from the time the disease becomes symptomatic until the start of treatment. In most developed countries there are specific referral guidelines for the early diagnosis and treatment of patients. However, there seems to be a lack of awareness of how to use referral pathways correctly. In the UK, the “NHS Cancer Plan”,15 implemented in 2000, aimed to ensure that the time from primary care consultation to the first specialist consultation should be no more than 2 weeks. In the results published by Malik et al.,12 78% of referrals met the referral criteria of the guideline, but only 15% of patients had primitive malignant tumours. In our study, only in 83 patients (35.93%) was the information provided by the primary care physician considered adequate, in contrast to the results of Malik et al.12 These figures highlight the need to improve the basic specific training of primary care physicians in musculoskeletal oncology; this could be achieved through the appropriate training.

Pencavel et al.16 studied the impact of the abovementioned clinical practice guideline15 on the referral of patients to their soft tissue sarcoma unit over a period of 5 consecutive years (January 2004 - December 2008). Most of their patients continued to arrive via the ordinary referral route. The number of referrals through the 2-week route increased 25-fold over the 5 years of the study. However, this increase only accounted for 1% of the sarcomas treated in the unit. In absolute numbers, of the 154 patients who had come through the 2-week pathway, only a total of 12 (7.79%) had malignant disease. In our series, only 19 of the 231 patients referred (8.23%) had malignant disease. Although we counted primary malignant tumours, metastatic pathology and aggressive benign tumours in the same group, this percentage is lower than that published by Malik et al.12 and, although slightly higher than that of Pencavel et al.,16 it is well below what is expected. Furthermore, of the total 101 patients with primary, metastatic, or benign aggressive malignant tumours who were treated at the hospital's UTME during the study period, only 19 (18.81%) were referred through the specific referral pathway. In short, although the pathway is useful, it seems to be used insufficiently and inefficiently.

In our series, the mean time from the request for referral from primary care to the first consultation with the specialist was 18.11 days (range 0–100). The result is slightly higher than the ideal delay time for this pathway, which is set at 2 weeks, but is a much lower result than those published by Goedhart et al.17 who reported pre-hospital delay times of 57.8 days for osteosarcoma patients, 103.6 days for Ewing's sarcoma patients and 197.2 days for chondrosarcoma patients. However, in the series of Malik et al.,12 95% of the patients were seen within 14 days following referral. In our series, just over half (52.63%) of the patients were seen within this time interval.

The median time from first consultation to initiation of treatment was 27 days. Comparing our results with the published literature, Malik et al.12 managed to initiate treatment of all patients with malignant tumours within 30 days of referral and Featherall et al.18 in their study on 8648 patients with localised high-grade soft tissue sarcomas, concluded that a delay in starting treatment of more than 42 days decreased patients’ overall survival.

In terms of the importance of professional experience in the management of musculoskeletal tumour disease, training in orthopaedic oncology during residency in the specialty of orthopaedic surgery and traumatology is essential to establish the basic concepts, fundamentally in terms of the principles of diagnostic biopsy and its risks.19 In our study, from the results of the kappa index values to analyse concordance between assessors with different degrees of specific training, it is striking that the discrepancy was lower between the professionals with intermediate training compared to those with more expert training and those with less training. Comparing the results of the 3 groups, we conclude that most of the practitioners had a success rate of more than 85% in early appointments for malignancies. From all this, we deduce that the ideal assessor should have moderate specific training, combined with basic oncological knowledge, to identify all patients with clinical and/or radiological suspicion of malignant musculoskeletal disease, with the reasonable concern that because their experience is still insufficient and, although more requests are brought forward in the total, patients with musculoskeletal malignant disease must not be left without early appointments through a false sense of security. Arguably the assessment of requests for early appointments for patients with suspected musculoskeletal malignancy can be entrusted to traumatologists with moderate specific training in musculoskeletal oncology, without exclusive specialisation in musculoskeletal oncology. The need for this sub-specialisation is more relevant to the subsequent management of the patient, i.e., confirmatory diagnosis (biopsy), treatment and follow-up.

Our study has certain limitations. The main limitation is that it is a retrospective study, with the information bias inherent to this type of study. The sample size is small, explained by the low incidence of malignant musculoskeletal tumour disease. Finally, there was a selection bias in the choice of re-assessors, which was based on the criterion of years of specific training in orthopaedic oncology, and the groups created were unbalanced in terms of the number of participants. However, despite these limitations, we believe that the aim of the study, which was to analyse the use and effectiveness of a management tool, was achieved.

In conclusion, the SCAE-SM computer application as a tool for the management and early care of patients with malignant musculoskeletal tumour disease is useful, although the pathway is inadequately used. There seems to be a clear need for its dissemination and standardisation, and for specific training programmes on the warning signs and symptoms of malignant musculoskeletal disease, both in primary and hospital care.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

FundingThe study was approved by the i+12 Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid.

The study was funded through the “Proyectos de Inicio a la Investigación de la Fundación SECOT” (Research initiation projects of the SECOT foundation) grant, announced in 2018.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank the specialists who collaborated in the study: J.A. Maderuelo Fernández, J. López Goenaga, D. Bustamante Recuenco, M. Peleteiro Pensado, M.I. Mora Fernández, J. Fernández Fuertes, I. Barrientos Ruiz, V.M. Bárcena Tricio, F. Arias Martín.