Pathology of the musculoskeletal system is a frequent cause of healthcare requirements. Knowledge of musculoskeletal medicine (MSM) should be essential for most specialties. Unfortunately, many medical intern residents (MIRs) admit to a lack of confidence and competence in this field.

Material and methods50 recently hired MIRs (32 of whom were COT residents from the Comunidad Valenciana) completed the Freedman and Berstein test of basic competency in MSM. In addition, they completed a questionnaire about their confidence in performing five common tasks in clinical practice and their perception of the curricular importance of medicine in their academic training.

ResultsThe overall mean score obtained on the test was 69.44% (SD 13.32%), while the specific score for 5 “red flags” questions was 14.34% (SD 2.58%). Both of them showed significant differences between COT residents and other specialties.

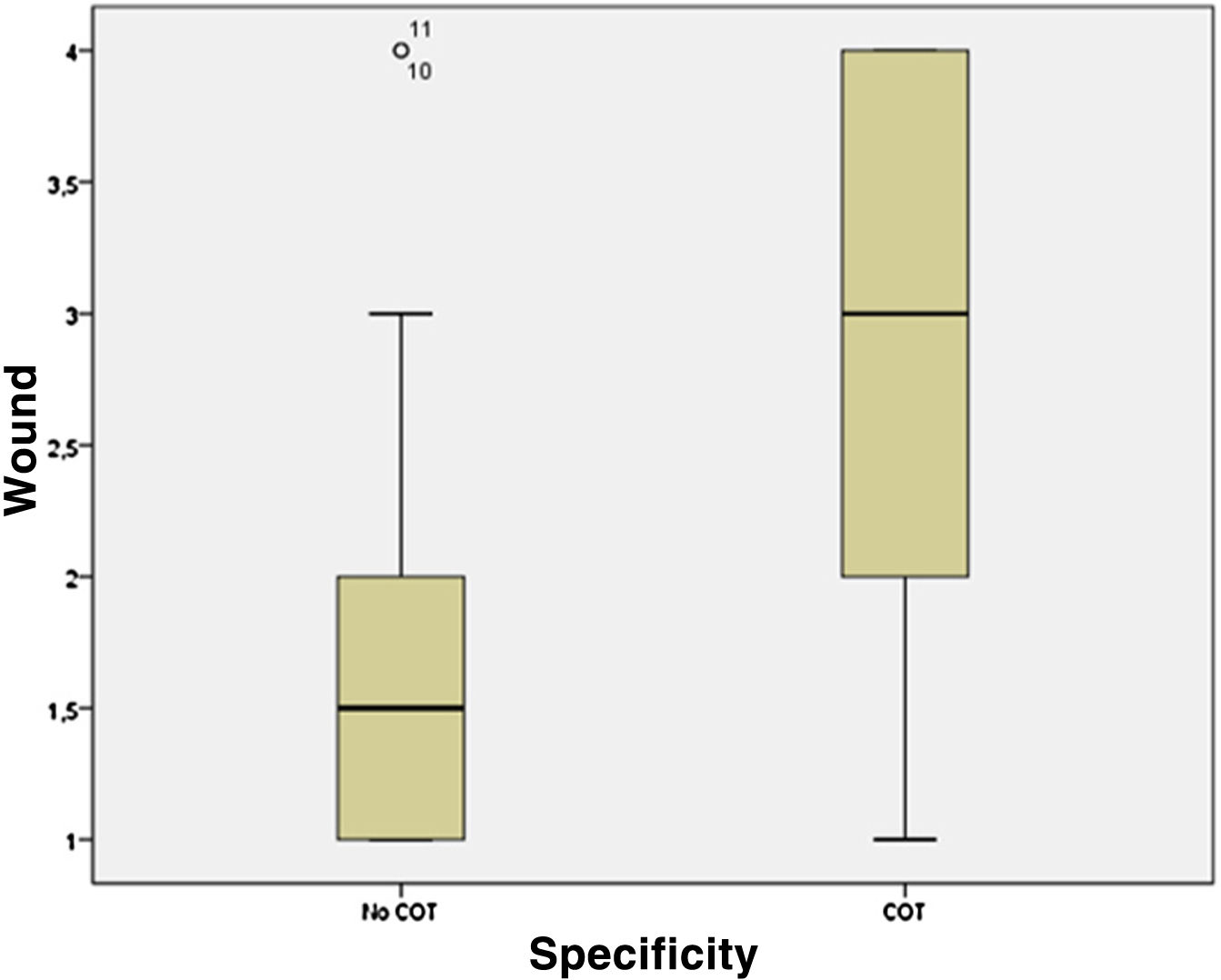

The median obtained in the evaluation of the level of confidence in wound examination was 2 above 5 (IQR 2), with significant differences (p=.014) between the COT group and other specialties. The perception of the time spent in the faculty on MSM was considered adequate (median 3, IQR 1). 64% of participants would modify the approach to the practical part of the curriculum in MME.

ConclusionsThe overall test was passed by 50% of the residents, which shows that the teaching of MME is deficient during the university and pre-MIR training period. We believe that it is important to plan training actions to increase the knowledge and skills necessary for its correct handling; this way, the system would be more efficient with better health care and a better screening of specialised derivations.

La enfermedad del sistema musculoesquelético es una causa frecuente de demanda asistencial. El conocimiento en medicina musculoesquelética (MME) debe ser esencial para gran parte de las especialidades. Desafortunadamente, gran parte de los médicos internos residentes (MIR) reconocen tener falta de confianza y de competencia en este campo.

Material y métodosCincuenta MIR recién incorporados a su plaza (32 de ellos residentes de COT de la Comunidad Valenciana) completaron el test de competencia básica en MME de Freedman y Berstein. Además, realizaron un cuestionario sobre el grado de confianza al momento de desempeñar cinco tareas habituales en la práctica clínica y sobre la percepción de la carga curricular de MME en su formación académica.

ResultadosLa puntuación media global obtenida en el test fue de 69,44% (SD 13,32%), mientras que la puntuación concreta para cinco preguntas que se consideraban «banderas rojas» fue de 14,34% (SD 2,58%). Ambas mostraron diferencias significativas entre los residentes de COT y otras especialidades.

La mediana obtenida en la valoración del nivel de confianza en la exploración de heridas fue de 2 sobre 5 (IQR 2), con diferencias significativas (p=0,014) entre el grupo COT y el de otras especialidades. La percepción del tiempo dedicado en la facultad en materia de MME fue considerada como adecuada (mediana 3, IQR 1). El 64% modificaría el planteamiento de la parte práctica del currículo en MME.

ConclusionesLa prueba global fue superada por el 50% de los residentes, lo cual pone de manifiesto que la enseñanza en MME es deficitaria durante el periodo universitario y formativo preMIR. Consideramos primordial la planificación de acciones formativas que se traduzca en un aumento de los conocimientos y aptitudes necesarias para su correcto manejo, ya que ello se traduciría en una mayor agilidad del sistema, una mejor asistencia sanitaria y un mejor cribado de derivaciones especializadas.

Diseases of the musculoskeletal system are among the most frequent in terms of disability, handicap and demand for medical consultation. In Spain, musculoskeletal diseases are the leading cause of sick leave, consuming nearly 2% of the gross domestic product.1 In Europe, it is the group of diseases that causes the greatest number of years of life lost and lived with disability, ahead of cancer and cardiovascular diseases.2 It thus represents a very significant percentage of the care burden in primary care consultation, since if we group diseases by apparatus and systems, in patients over 15 years of age, musculoskeletal disease is the most prevalent in Spain.3 In an emergency department, traumatic musculoskeletal emergencies account for 25% of the total and non-traumatic musculoskeletal disease is the most frequent reason for consultation (14%), surpassing digestive (9%), respiratory (6%) or circulatory (7%) non-traumatic diseases.4

Its management involves a wide range of professionals: internal medicine specialist, rheumatologists, rehabilitation specialists, orthopaedic surgeons (OTS), paediatricians and primary care physicians.5 In fact, it is the latter who receive the greatest burden of care and are responsible for making referrals to the second level or specialised care. Given that the proportion of patients with musculoskeletal manifestations has increased considerably in recent years, adequate training in this field would increase the quality of care and reduce the additional cost of misguided patients.

Unfortunately, a large number of medical intern residents (MIRs) admit to lacking confidence and competence when dealing with this type of patient.6 Some studies in European and North American settings have shown deficits in training and competence in musculoskeletal disease in recent medical graduates,5,7–10 in family doctors11,12 and even internal medicine specialists.13 Various academic institutions and scientific societies5,14–17 have assessed the level of knowledge acquired in musculoskeletal medicine (MSM) in medical students and graduates using the Freedman and Berstein basic competency test in MSM.5 There appears to be insufficient academic preparation in this area during the undergraduate training process.18 There is currently a growing concern that the significant impact of these diseases on healthcare activity requires a better adaptation of the curricular load of this subject in training plans.5,6,14,18,19

The aim of our study was to obtain information on the knowledge and skills acquired in musculoskeletal disease by medical graduates at the time of joining the residency programme of the Spanish National Health System, in order to identify possible shortcomings in the current learning system, as well as to propose changes aimed at improving the curriculum.

Material and methodThis is a multicentre cross-sectional analytical study conducted in the 15 hospitals with MIR training in OTS in the Valencian Community, after approval by the local Clinical Research Ethics Committee. The MIRs who passed the 2020 tests and obtained a post in orthopaedic surgery were invited to participate, as well as the first year MIRs from the other specialties of the Hospital Arnau de Vilanova in Valencia. The collaboration of the tutors of the OTS residents of the hospitals of the Valencian Community was requested, as well as that of the president of the teaching committee of the Arnau de Vilanova Hospital in Valencia.

The doctors who were about to enter their first year of residency completed 2 questionnaires assessing perceived knowledge and competencies on the day they were to take up their post as MIRs. The anonymity of the study participants was maintained at all times, with the exception of knowing whether they were OTS residents or from another specialty.

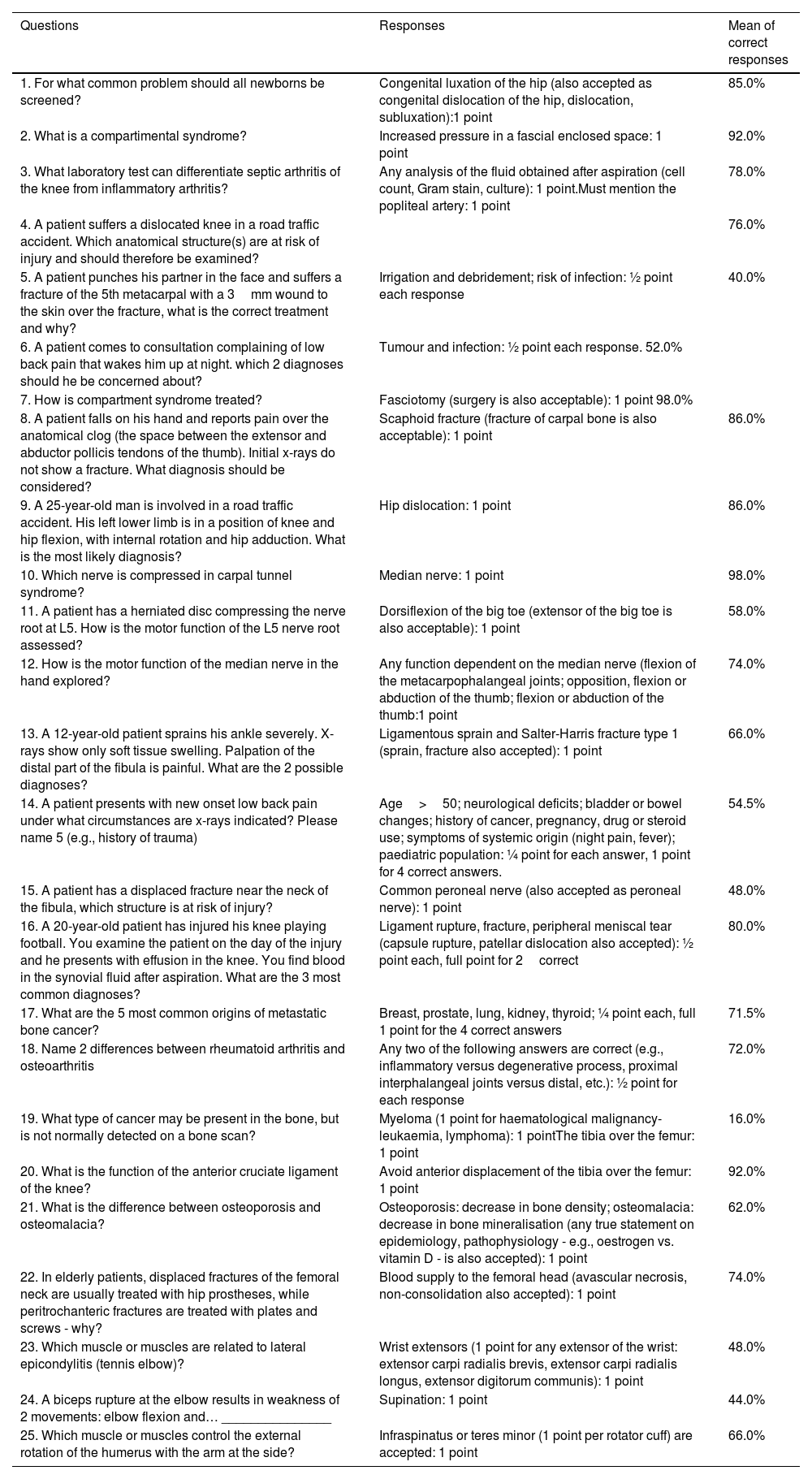

The Freedman and Berstein basic competency test in musculoskeletal medicine was used to assess knowledge. This test was developed and validated by 124 directors of OTS residency programmes in the United States and has been widely used in different countries to assess the knowledge of residents and medical graduates. Two researchers with university teaching experience independently translated the questions from English into Spanish. A third OTS professor reviewed both translations and resolved any discrepancies, resulting in a consensual version. The questionnaire consists of 25 short-answer questions. Each question is graded on a scale between 0% and 100% according to its importance in the development of care practice (Table 1). The maximum score per question is 1 point and partial scores can be obtained for multiple choice questions. Correction was anonymous and followed the guidelines of the answer template. The raw score was multiplied by 4 to obtain a percentage result and a pass mark of 73.1% was established.4 In order to be able to detect what are known as “red flags”, questions 2, 4, 5, 6 and 7 were specifically selected. This term encompasses any situation that alerts us to the possible presence of serious illness that may cause irreversible disability if not acted upon appropriately.20

Musculoskeletal medicine basic competence exam.

| Questions | Responses | Mean of correct responses |

|---|---|---|

| 1. For what common problem should all newborns be screened? | Congenital luxation of the hip (also accepted as congenital dislocation of the hip, dislocation, subluxation):1 point | 85.0% |

| 2. What is a compartimental syndrome? | Increased pressure in a fascial enclosed space: 1 point | 92.0% |

| 3. What laboratory test can differentiate septic arthritis of the knee from inflammatory arthritis? | Any analysis of the fluid obtained after aspiration (cell count, Gram stain, culture): 1 point.Must mention the popliteal artery: 1 point | 78.0% |

| 4. A patient suffers a dislocated knee in a road traffic accident. Which anatomical structure(s) are at risk of injury and should therefore be examined? | 76.0% | |

| 5. A patient punches his partner in the face and suffers a fracture of the 5th metacarpal with a 3mm wound to the skin over the fracture, what is the correct treatment and why? | Irrigation and debridement; risk of infection: ½ point each response | 40.0% |

| 6. A patient comes to consultation complaining of low back pain that wakes him up at night. which 2 diagnoses should he be concerned about? | Tumour and infection: ½ point each response. 52.0% | |

| 7. How is compartment syndrome treated? | Fasciotomy (surgery is also acceptable): 1 point 98.0% | |

| 8. A patient falls on his hand and reports pain over the anatomical clog (the space between the extensor and abductor pollicis tendons of the thumb). Initial x-rays do not show a fracture. What diagnosis should be considered? | Scaphoid fracture (fracture of carpal bone is also acceptable): 1 point | 86.0% |

| 9. A 25-year-old man is involved in a road traffic accident. His left lower limb is in a position of knee and hip flexion, with internal rotation and hip adduction. What is the most likely diagnosis? | Hip dislocation: 1 point | 86.0% |

| 10. Which nerve is compressed in carpal tunnel syndrome? | Median nerve: 1 point | 98.0% |

| 11. A patient has a herniated disc compressing the nerve root at L5. How is the motor function of the L5 nerve root assessed? | Dorsiflexion of the big toe (extensor of the big toe is also acceptable): 1 point | 58.0% |

| 12. How is the motor function of the median nerve in the hand explored? | Any function dependent on the median nerve (flexion of the metacarpophalangeal joints; opposition, flexion or abduction of the thumb; flexion or abduction of the thumb:1 point | 74.0% |

| 13. A 12-year-old patient sprains his ankle severely. X-rays show only soft tissue swelling. Palpation of the distal part of the fibula is painful. What are the 2 possible diagnoses? | Ligamentous sprain and Salter-Harris fracture type 1 (sprain, fracture also accepted): 1 point | 66.0% |

| 14. A patient presents with new onset low back pain under what circumstances are x-rays indicated? Please name 5 (e.g., history of trauma) | Age>50; neurological deficits; bladder or bowel changes; history of cancer, pregnancy, drug or steroid use; symptoms of systemic origin (night pain, fever); paediatric population: ¼ point for each answer, 1 point for 4 correct answers. | 54.5% |

| 15. A patient has a displaced fracture near the neck of the fibula, which structure is at risk of injury? | Common peroneal nerve (also accepted as peroneal nerve): 1 point | 48.0% |

| 16. A 20-year-old patient has injured his knee playing football. You examine the patient on the day of the injury and he presents with effusion in the knee. You find blood in the synovial fluid after aspiration. What are the 3 most common diagnoses? | Ligament rupture, fracture, peripheral meniscal tear (capsule rupture, patellar dislocation also accepted): ½ point each, full point for 2correct | 80.0% |

| 17. What are the 5 most common origins of metastatic bone cancer? | Breast, prostate, lung, kidney, thyroid; ¼ point each, full 1 point for the 4 correct answers | 71.5% |

| 18. Name 2 differences between rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis | Any two of the following answers are correct (e.g., inflammatory versus degenerative process, proximal interphalangeal joints versus distal, etc.): ½ point for each response | 72.0% |

| 19. What type of cancer may be present in the bone, but is not normally detected on a bone scan? | Myeloma (1 point for haematological malignancy-leukaemia, lymphoma): 1 pointThe tibia over the femur: 1 point | 16.0% |

| 20. What is the function of the anterior cruciate ligament of the knee? | Avoid anterior displacement of the tibia over the femur: 1 point | 92.0% |

| 21. What is the difference between osteoporosis and osteomalacia? | Osteoporosis: decrease in bone density; osteomalacia: decrease in bone mineralisation (any true statement on epidemiology, pathophysiology - e.g., oestrogen vs. vitamin D - is also accepted): 1 point | 62.0% |

| 22. In elderly patients, displaced fractures of the femoral neck are usually treated with hip prostheses, while peritrochanteric fractures are treated with plates and screws - why? | Blood supply to the femoral head (avascular necrosis, non-consolidation also accepted): 1 point | 74.0% |

| 23. Which muscle or muscles are related to lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow)? | Wrist extensors (1 point for any extensor of the wrist: extensor carpi radialis brevis, extensor carpi radialis longus, extensor digitorum communis): 1 point | 48.0% |

| 24. A biceps rupture at the elbow results in weakness of 2 movements: elbow flexion and… _______________ | Supination: 1 point | 44.0% |

| 25. Which muscle or muscles control the external rotation of the humerus with the arm at the side? | Infraspinatus or teres minor (1 point per rotator cuff) are accepted: 1 point | 66.0% |

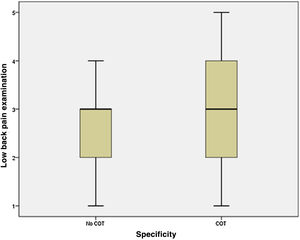

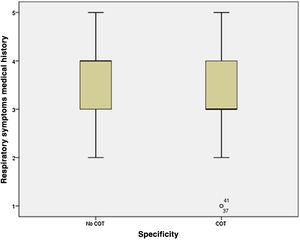

To assess the level of self-perceived competence, an adaptation of the Day et al.,14 questionnaire was used. The degree of confidence in performing 5 common clinical practice tasks in musculoskeletal and respiratory disease was determined for comparison: suturing a superficial knee wound, anamnesis and physical examination of a patient with low back pain, and anamnesis and physical examination of a patient with respiratory symptoms. The participating physician had to rate each activity on a scale of 1–5, where 1 corresponded to a complete lack of safety and 5 to complete safety.

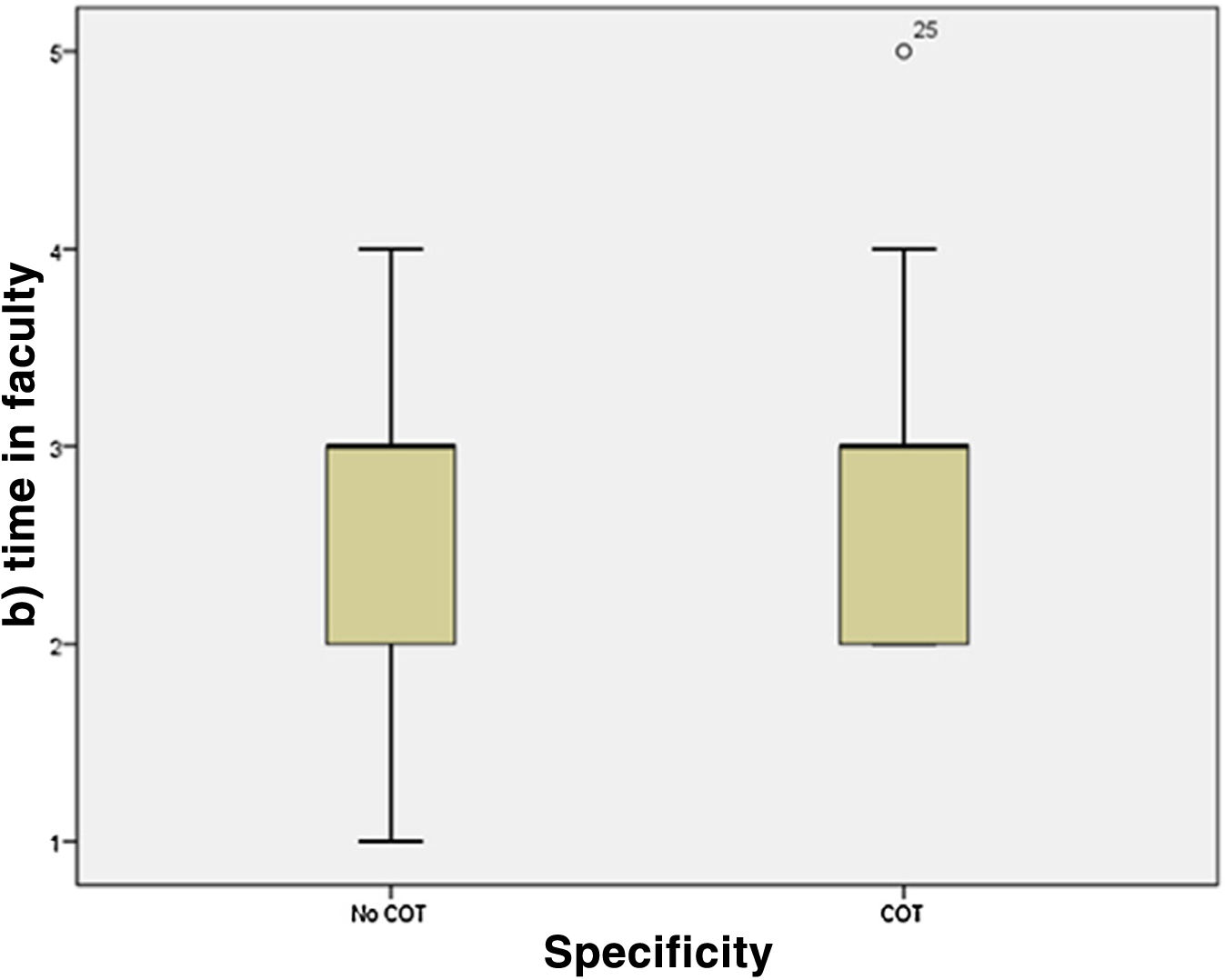

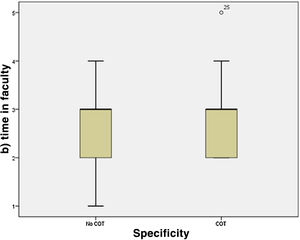

The personal perception of the amount of time spent on MSM at the university where they had been trained was also requested, scoring from 1 to 5 (1 if the amount of time was inadequate and 5 if it was excellent). Finally, a suggestions section was added in which the participating resident could present the changes that could be made to improve the university curriculum in MSM.

A descriptive analysis of the demographic variables was performed. Quantitative variables are shown with the mean and standard deviation (SD), applying the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to confirm their normality. Ordinal qualitative variables are expressed as median and interquartile range (IQR). The Student's t-test was used for unpaired data for continuous variables and Chi-square for qualitative variables. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was used for ordinal qualitative variables. The significance level was set at p<.05.

ResultsAll the OTS Services of the Valencian Community agreed to participate, as well as the non-OTS residents of the Hospital Arnau de Vilanova. A total of 50 residents were evaluated, 32 (64%) of whom were OTS residents (3 had also completed another residency previously) and 18 (36%) from other specialties. The demographic characteristics are shown in Table 2.

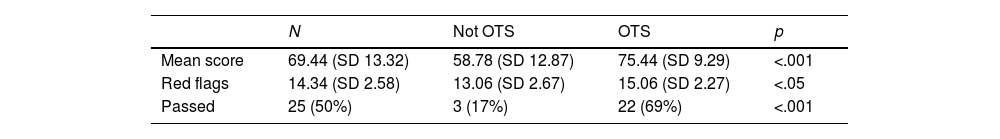

The overall mean score obtained on the test was 69.44% (SD 13.32%), while the specific score for the 5 questions considered “red flags” was 14.34% (SD 2.58%). The overall test was passed by 50% of the residents (n=25). When results were compared between OTS residents and other specialties statistically significant differences were found (Table 3). The regression model was .37 for the variable specialty. On the other hand, no significant differences were found with respect to the variables of: age, years since graduation, previous to current specialty, as well as years spent in the previous specialty.

Total mean score, mean score in questions considered to be red flags and percentage of passes according to the specialty.

| N | Not OTS | OTS | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean score | 69.44 (SD 13.32) | 58.78 (SD 12.87) | 75.44 (SD 9.29) | <.001 |

| Red flags | 14.34 (SD 2.58) | 13.06 (SD 2.67) | 15.06 (SD 2.27) | <.05 |

| Passed | 25 (50%) | 3 (17%) | 22 (69%) | <.001 |

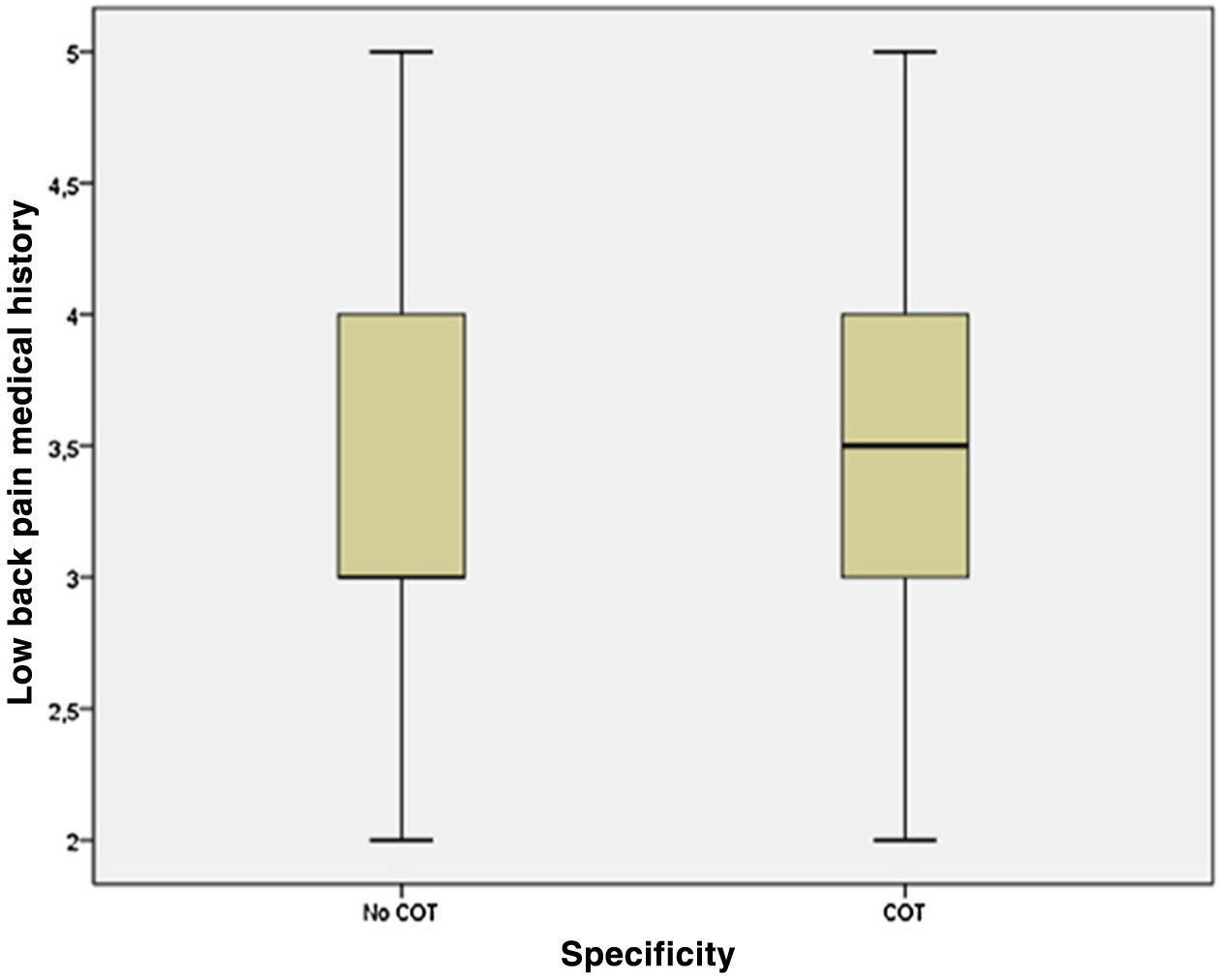

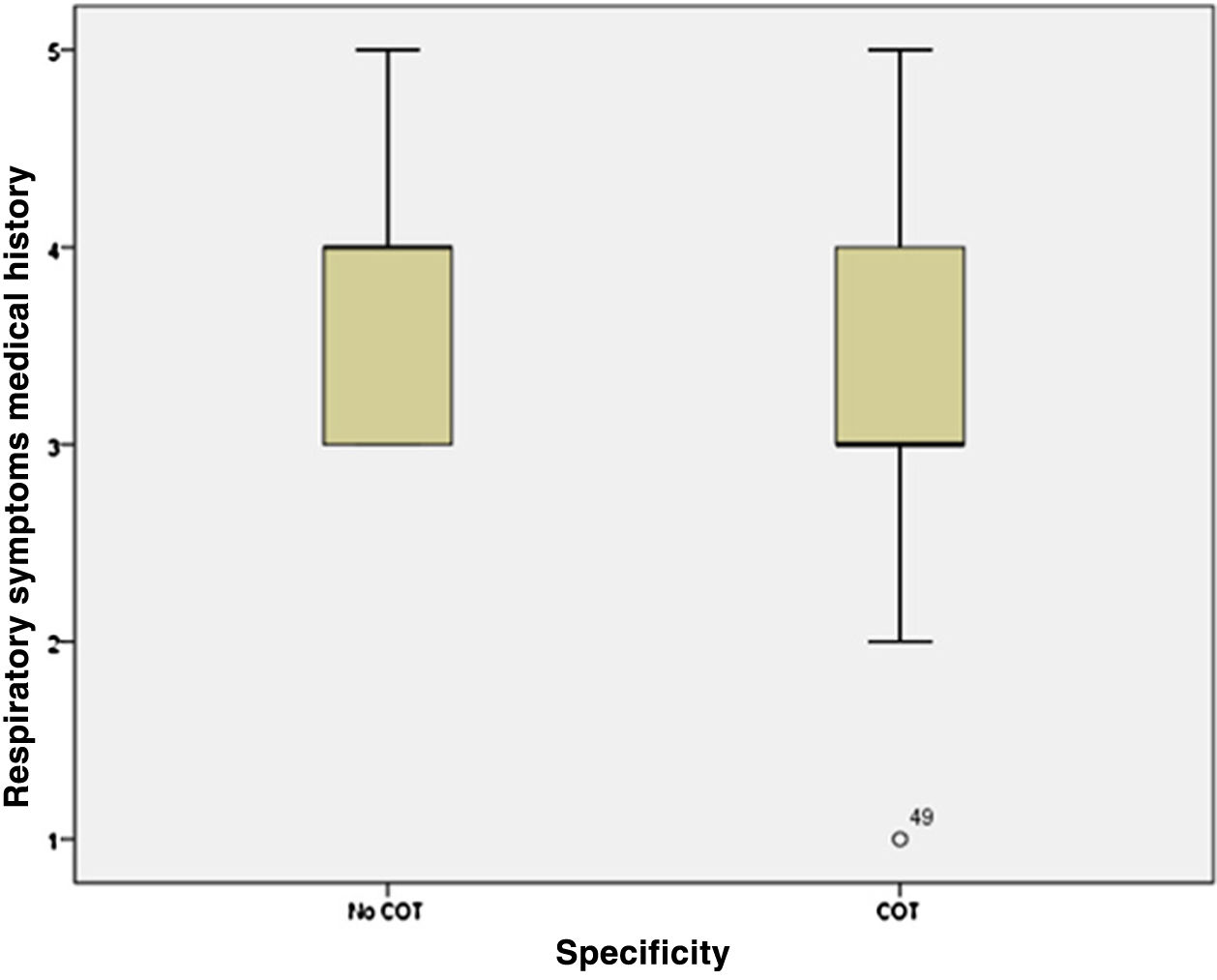

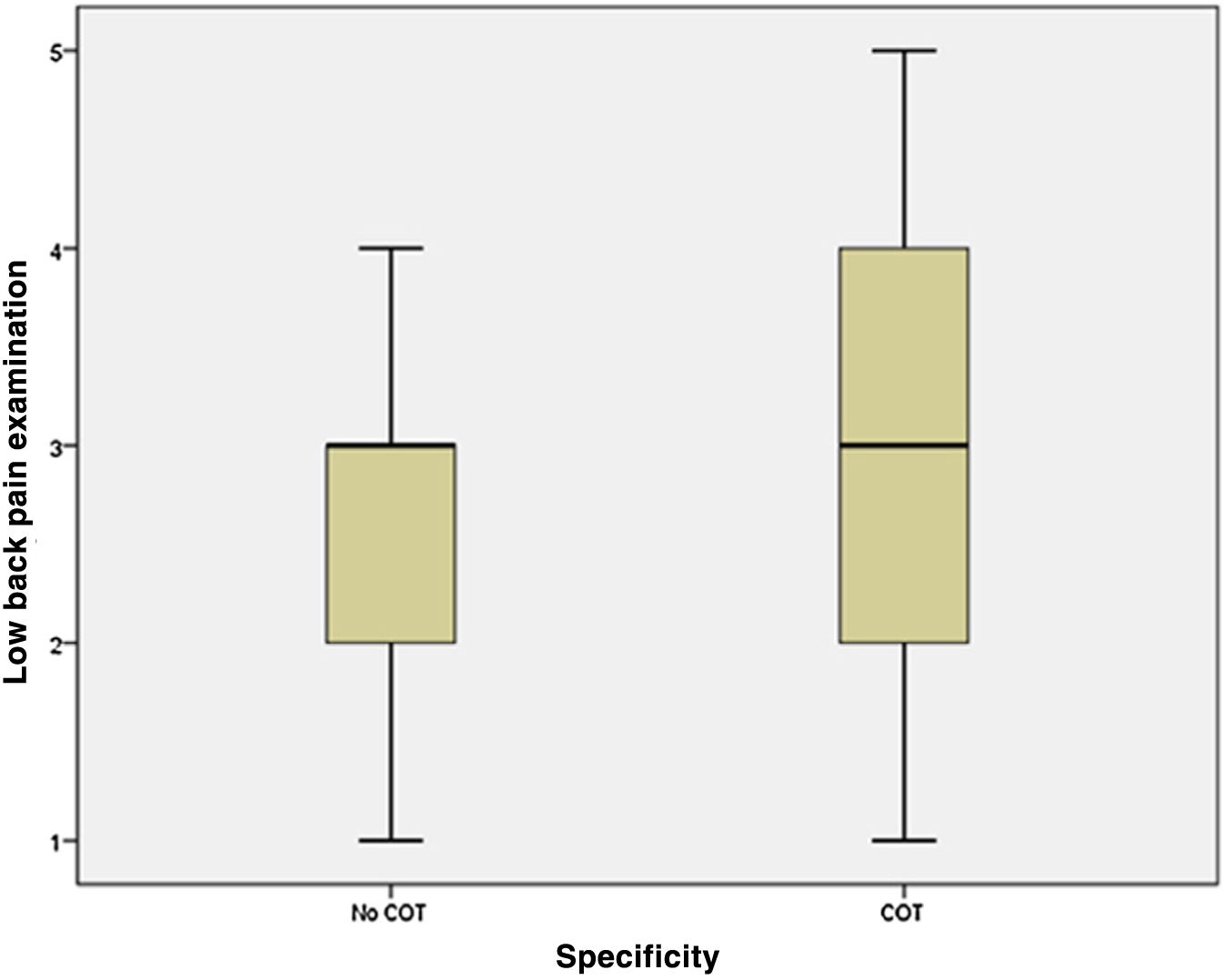

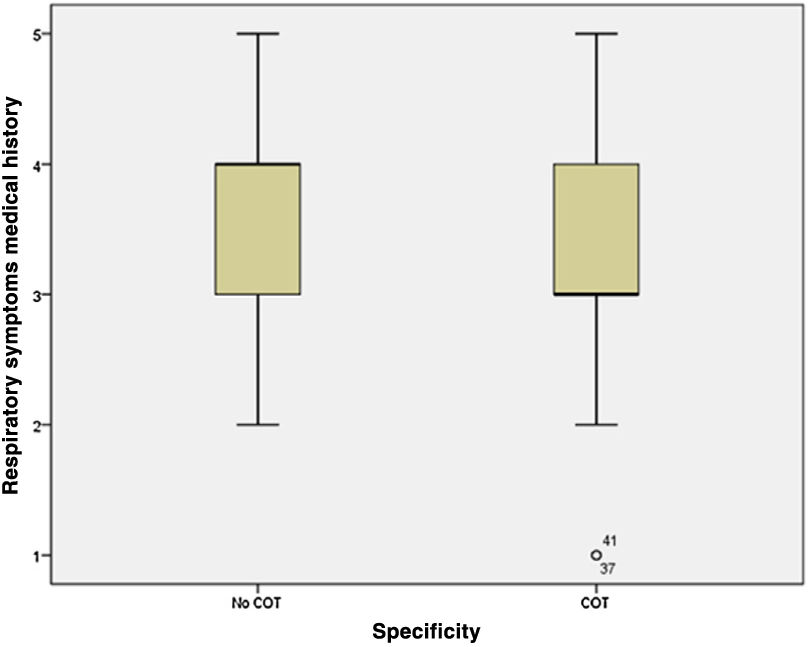

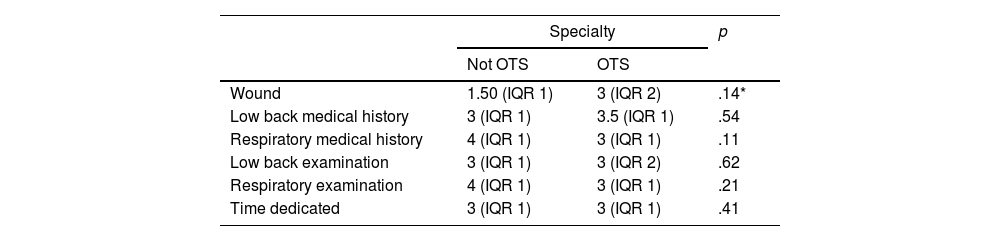

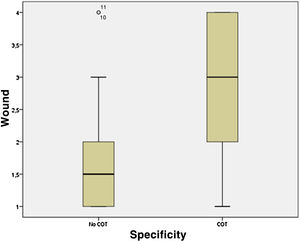

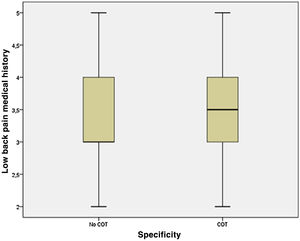

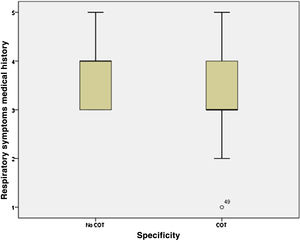

Perceived self-confidence was assessed on a scale from 1 (not at all confident) to 5 (completely confident). The median confidence level assessment for the different clinical practice activities was 2 (IQR 2) for wound examination, 3 (IQR 1) and 4 (IQR 1) for lumbar and respiratory history taking respectively, and 3 for both lumbar (IQR 2) and respiratory (IQR 1) examination. The comparison of wound examination in the OTS group with respect to other specialties showed significant differences (p=.014). The differences and distribution between groups are shown in Table 4 and Figs. 1–6.

Perception of confidence in performance of activities according to specialty.

| Specialty | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Not OTS | OTS | ||

| Wound | 1.50 (IQR 1) | 3 (IQR 2) | .14* |

| Low back medical history | 3 (IQR 1) | 3.5 (IQR 1) | .54 |

| Respiratory medical history | 4 (IQR 1) | 3 (IQR 1) | .11 |

| Low back examination | 3 (IQR 1) | 3 (IQR 2) | .62 |

| Respiratory examination | 4 (IQR 1) | 3 (IQR 1) | .21 |

| Time dedicated | 3 (IQR 1) | 3 (IQR 1) | .41 |

The perception of the time spent in the faculties on MSM was considered adequate (median 3, IQR 1), with no differences being observed between residents in OTS and those in other specialties. Finally, with regard to the changes that the residents would propose in terms of academic training, 64% would modify the approach to the practical part of the MSM curriculum, 10% would do so with regard to the theoretical load and 26% would not see the need for any training change.

DiscussionMusculoskeletal disease is one of the main reasons for consultation, both in primary care and in the emergency department, so newly trained physicians need to be familiar with its diagnosis and management and integrate this knowledge and skills into their training. Although there are studies that evaluate the acquisition of this knowledge in the university training period,5,10,14,15,17,20 to date there has been no study that assesses this preparation among graduates who join the Spanish National Health System as residents.

The results we obtained in the Freedman and Berstein basic competence examination in MSM (50% pass rate) confirm the perceived concern about the lack of university preparation received in this field. When we compare our data with those of similar studies in neighbouring countries, we observe a higher pass rate among our residents. However, these are still insufficient results given the growing demand for care, the progressive ageing of the population and the increase in the number of diseases related to bones and joints.5,10,17

The preparation for the MIR selective test may be one of the reasons for the variation in the pass rate compared to other training systems. The MIR exam is a theoretical knowledge assessment test using an objective multiple-choice questionnaire, with the aim of gaining access to medical specialist training in Spain. Unlike other competitive examinations, there is no official syllabus, which is why study time is prioritised according to the relevance of each subject. Although it is a demanding test, it cannot be the way to make up for the lack of university training in musculoskeletal issues, since, compared to other subjects, the percentage of questions dedicated to this disease is lower. For example, an analysis of MIR questions over the last 15 years showed that only 3.4% of the questions on OTS were about OTS and it was ranked 15th among the 20 most frequently asked specialties.21

Another logical explanation for the higher pass rate compared to other countries would be the high percentage of OTS residents included in our study, 64% compared to the 10% published in the literature.5,10 An internal comparison of the OTS group with respect to other specialties shows that, as in other series,5,10 the percentage of passes and the mean score is higher among OTS residents (difference of 16.7%; p<.001). In fact, it has been found that the specialty itself would explain 37% of the overall mark (regression model .37 for specialty). These rates suggest that there is a certain motivation towards MSM on the part of the OTS group or that, at least, there has been greater contact with this type of disease through training practices.

On the other hand, the percentage of correct answers to questions considered as “red flags” reflects an insufficient result, 14.34% out of a total of 20%, if we remember that their inadequate assessment and management can have very serious repercussions for the patient. In fact, only one third of the residents got 4 or more of these questions right. Only the questions related to the diagnosis and treatment of compartment syndrome (questions 2 and 7) were answered correctly by more than 90% of residents, but less than half of them were able to deal with the urgent management of an open fracture of the hand (question 5) or to identify the causes of low back pain with atypical characteristics (question 6).

The dubious academic preparation in MSM, as well as the lack of clinical practice in its management, becomes even more evident when assessing the resident's confidence during the tasks and performance of their care activity.14,20 The lack of confidence increases when suturing a superficial knee wound (median 2 IQR 2), and is even more significant when comparing the skills of OTS residents with the other specialties (median 2 and 1.5 respectively; p<.05). Furthermore, when comparing the anamnesis and examination of low back pain with respect to respiratory disease, a distribution of confidence with more dispersed values is found, with a particularly striking trend towards lower confidence values in the approach to low back pain and higher values in the approach to respiratory disease.

Despite the fact that the overall results obtained reflect a significant lack of training, the perceptions of the residents themselves are different. The majority considered the time devoted to this subject during the university course to be adequate, although a high percentage would modify the approach to practical training. It is true that an increase in the number of teaching hours dedicated to MSM does not reflect a higher level of knowledge and skill acquisition, but it has been shown that greater exposure to clinical practice would improve the quality and durability of the knowledge acquired.5,17,22 Therefore, a possible solution to the shortage of MSM skills in the medium and long term may include a change in the way MSM is taught, opting for a less theoretical and much more practical approach.5,15

Limitations of our studyAlthough we draw some very relevant conclusions from our study, we assume that it has some limitations. The first is defined by the validity of the Freedman and Berstein test itself. The original authors were aware of the weaknesses of the test in relation to the distribution of topics, the wording and construction of the questions, as well as the open-ended format.5 However, these shortcomings cannot invalidate either the results or the conclusions that can be drawn from the questionnaire. We have encountered the disadvantage of not having other validated alternative tests that assess MSM knowledge and that in turn allow us to determine the reliability and reproducibility of the Freedman and Berstein test. It is noteworthy that this questionnaire has been widely used by universities and hospitals in the postgraduate assessment of musculoskeletal disease.5–20,22

Secondly, the selected population may not be a representative sample of the total number of medical school graduates in the state. Our sample is largely made up of OTS residents and to a lesser extent of residents from other specialties. Although this is an unequal sample, we believe that it can serve as a starting point in the investigation of the causes of such a disparity in the knowledge acquired between the two groups. Furthermore, although the group that includes specialties other than OTS is very heterogeneous, they share the peculiarity of the management of musculoskeletal disease in their daily clinical practice. We believe that the results of our study could be extrapolated to the rest of Spain, in order to avoid failure in a key field for the training of future professionals.

Lastly, we did not include measurements and assessments in terms of the resident's motivation towards the subject. This could explain the higher score among the OTS residents, and could in turn be considered a factor of confusion. One way to measure this motivation between the two groups would be to record the completion of a voluntary or compulsory rotation during their musculoskeletal training.

In conclusion, our results show a lack of education in musculoskeletal disease during the university and MIR training period. We consider it essential to plan training actions that will result in an increase in the knowledge and skills necessary for its correct management, as this would have an impact on better health care, greater agility of the system and better screening of specialised referrals.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

FundingThe authors declare that they have received no funding for the conduct of the present research, the preparation of the article, or its publication.

The authors would like to thank all the OTS services of the Community of Valencia and the teaching committee of the Hospital Arnau de Vilanova de Valencia for their collaboration in this project.