Several socioeconomic population factors have been related to the aetiology of Legg-Calve-Perthes disease (LCPD), such as its higher incidence in the urban population, living on the periphery of urban centres or residing at a certain latitude with respect to the world equator. The incidence in some other countries is known but the incidence of the process in our environment is unknown an important fact to allocate the social and health resources necessary for the treatment of the disease. Therefore, the aim of the present study is to determine the incidence of LCPD in Health Area 2 of Madrid.

Material and methodsThe incidence of LCPD is analysed in Healthcare Area 2 of Madrid because it is the Mediterranean area that has been scarcely studied. It is an area with very low geographic mobility, a medium–low socioeconomic level, and mostly composed of workers in companies in the secondary and tertiary sectors. The data were obtained from the hospital databases of Area 2 between the years 1994 and 2010. The inclusion criteria were the presence of LCPD and the territorial distribution of the population in Area 2 of Madrid.

ConclusionsThe incidence of LCPD in this Mediterranean population of an industrial area was 1.59 cases/year and 100,000 inhabitants, close to that found in populations of similar latitudes, but nevertheless it is an industrial area and socioeconomic level similar to United Kingdom populations with a much higher incidence.

Se han relacionado varios factores poblacionales socioeconómicos en la etiología de la enfermedad de Legg-Calvé-Perthes (ELCP), como son su mayor incidencia en población urbana, vivir en la periferia de núcleos urbanos o residir a una determinada latitud con respecto al ecuador terráqueo. Es conocida la incidencia en algunos otros países, pero se desconoce la incidencia del proceso en nuestro medio, hecho importante para acomodar los recursos sociosanitarios necesarios para el tratamiento de la enfermedad. Por todo ello, el objetivo del presente estudio es determinar la incidencia de la ELCP en el Área de Salud 2 de Madrid.

Material y métodosSe analiza la incidencia de ELCP en el Área de Salud 2 de Madrid por ser el área mediterránea una zona poco estudiada. Se trata de una zona con muy escasa movilidad geográfica, de nivel socioeconómico medio-bajo, e integrada en su mayoría por trabajadores de empresas del sector secundario y terciario. Los datos se han obtenido a partir de las bases de datos hospitalarias del Área 2 entre los años 1994 y 2010. Los criterios de inclusión fueron padecer la ELCP y la distribución territorial de la población en el Área 2 de Madrid.

ConclusionesLa incidencia de ELCP en esta población mediterránea de un área industrial fue de 1,59 casos por 100.000 habitantes-año, próxima a la encontrada en poblaciones de latitudes similares; pero, sin embargo, se trata de un área industrial con un nivel socioeconómico parecido al de las poblaciones de Reino Unido con una incidencia mucho mayor.

Multiple socio-economic factors associated with Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease (LCPD) have been identified throughout the literature. A higher incidence has been reported in urban versus rural populations in areas such as the city of Liverpool over a 13-year period, where different figures were recorded for residents in urban areas and those on the outskirts.1 Different data have led to the consideration of nutritional causes as determinants of this distribution. The association of LCPD with cases of malnutrition could be explained by decreased levels of insulin-like growth factors in patients with below-average height or delayed bone age.2

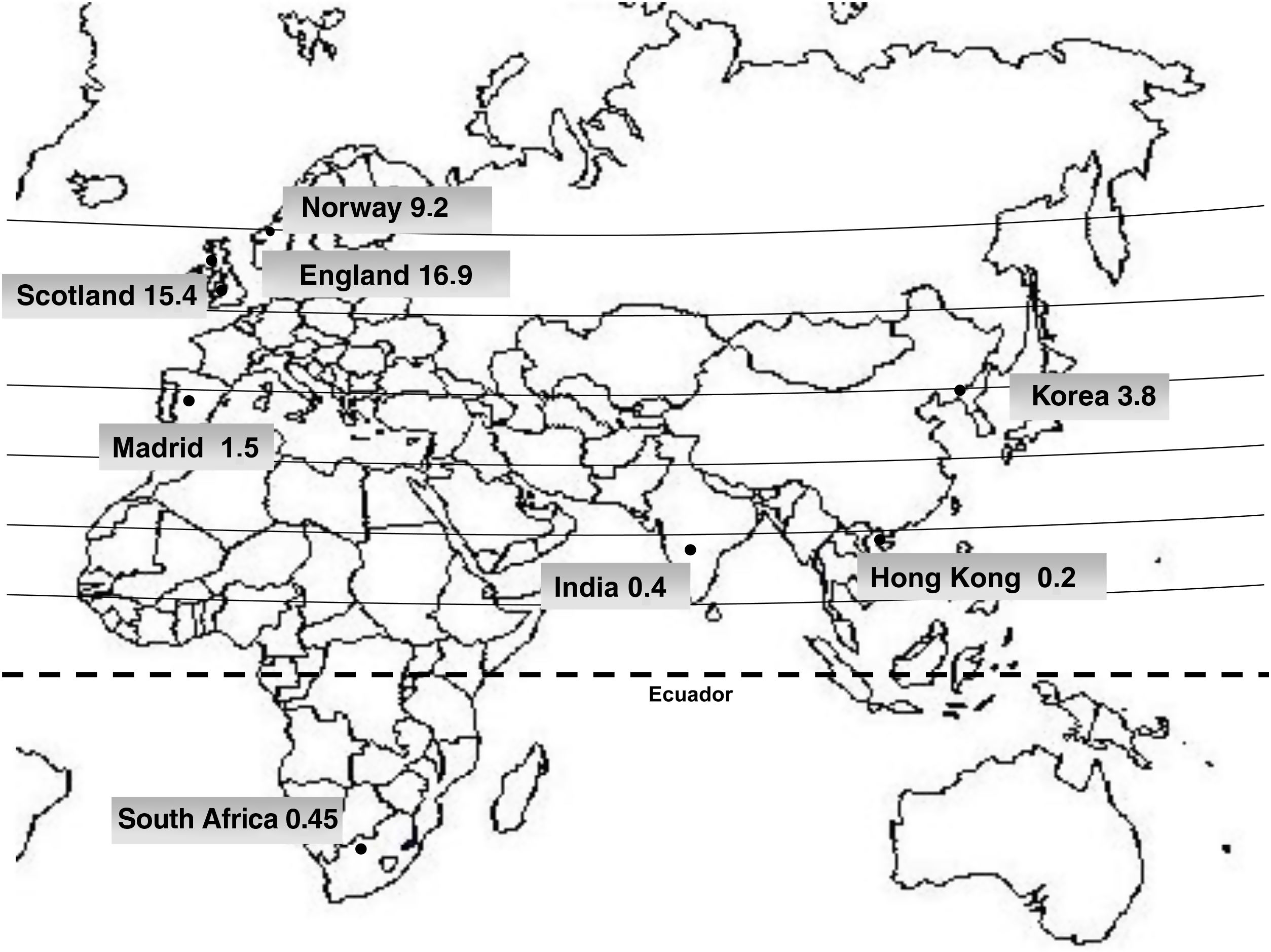

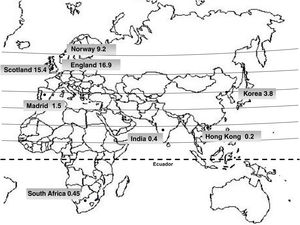

An association between a higher incidence of LCPD and certain races has also been described. Thus, the incidence in the Asian population varies from .2 per 100,000 population in Hong Kong, through .4 to 4.4 in India, to 3.8 in Korea.3 In the African population the incidence ranges from .45 in South Africa to 2.0 in Nigeria.4 In the Caucasian population of England,5,6 the incidence varies from 4.4 in some parts of the country to 16.9 in Liverpool in studies between 1976 and 1981, while later studies between 1990 and 19952 have shown a decrease in incidence to 8.7 per 100,000 population. In Scotland7–9 an incidence of 15.4 is described, in Norway10 of 9.2 and in Sweden of 8.5,9 with a relatively stable incidence since the 1970s. The incidence is clearly higher in the Caucasian population, followed by Asians and, lastly, Africans, where the lowest incidence occurs (Fig. 1). The incidence in Spain and in the Mediterranean area is unknown.

This study requires that the population area to be studied is known. The public health system of the Autonomous Community of Madrid in the period between 1994 and 2010 was organised into 11 health areas, with each area having an assigned population and a reference hospital with an allocation of resources that followed an exclusive criterion of territorial distribution of citizens. The reference hospital in Health Area 2 of Madrid provided the public health service for children on a compulsory and unique basis to the resident population of this demarcation, a premise that allowed the study population to be accurately defined.

According to data from the Ministry of Health, Consumption and Social Welfare, only .9% of the population had private health insurance, which shows us how little access there was to privately financed health services11 and even so, this small population group with private policies could also opt for the public health service offered by the reference hospital if they requested it.12–14 All this means that the incidence in this study population is sufficiently reliable to suggest that, with the exception of asymptomatic cases of LCPD, all of them would converge in the consulting rooms of this children's hospital.

The aim was to determine the incidence of PCPD in Health Area 2 and, with this, to establish the basis for planning the healthcare resources necessary for its management, as well as to be able to infer the incidence in other similar Mediterranean populations.

Material and methodsWe conducted a non-experimental, descriptive, longitudinal, ambispective, non-experimental epidemiological study of the incidence of LCPD. The clinical data on the disease were obtained manually from the patient lists of all the specific paediatric orthopaedic consultations in the corresponding area.

The inclusion criteria were all patients seen by the referral specialists in Area 2 of Madrid with a diagnosis of LCPD between 1994 and 2010. From 2011 onwards, other referral hospital centres were created and we stopped reviewing all patients with LCPD in this area. Only LCPD cases resident in Health Area 2 were included. In all cases the diagnosis was confirmed. Of the total number of cases, only one case was lost to follow-up, which gives significance to the adherence to the health system in the area.

The reference population data, such as the total population and the number of children under 10 years of age, were obtained from the National Institute of Statistics through the municipal census data for the years 1994 to 2010.11 Health Area 2, with a Mediterranean population of a medium–low socioeconomic level, is made up of urban centres adjacent to the capital, which include the towns of Coslada, Mejorada del Campo, San Fernando de Henares and Velilla de San Antonio, with an area of 12km2 at an altitude of 621m. The population is mainly dedicated to the service sector (72%) and industry (17%), forming part of the so-called industrial axis of the Corredor del río Henares. Its per capita income was €10,700. The birth rate was 9.20% and a low geographical mobility with a migration balance of .8% of the population, including 17% of foreign population. The incidence of LCPD was calculated for the general population and children under 10 years of age.

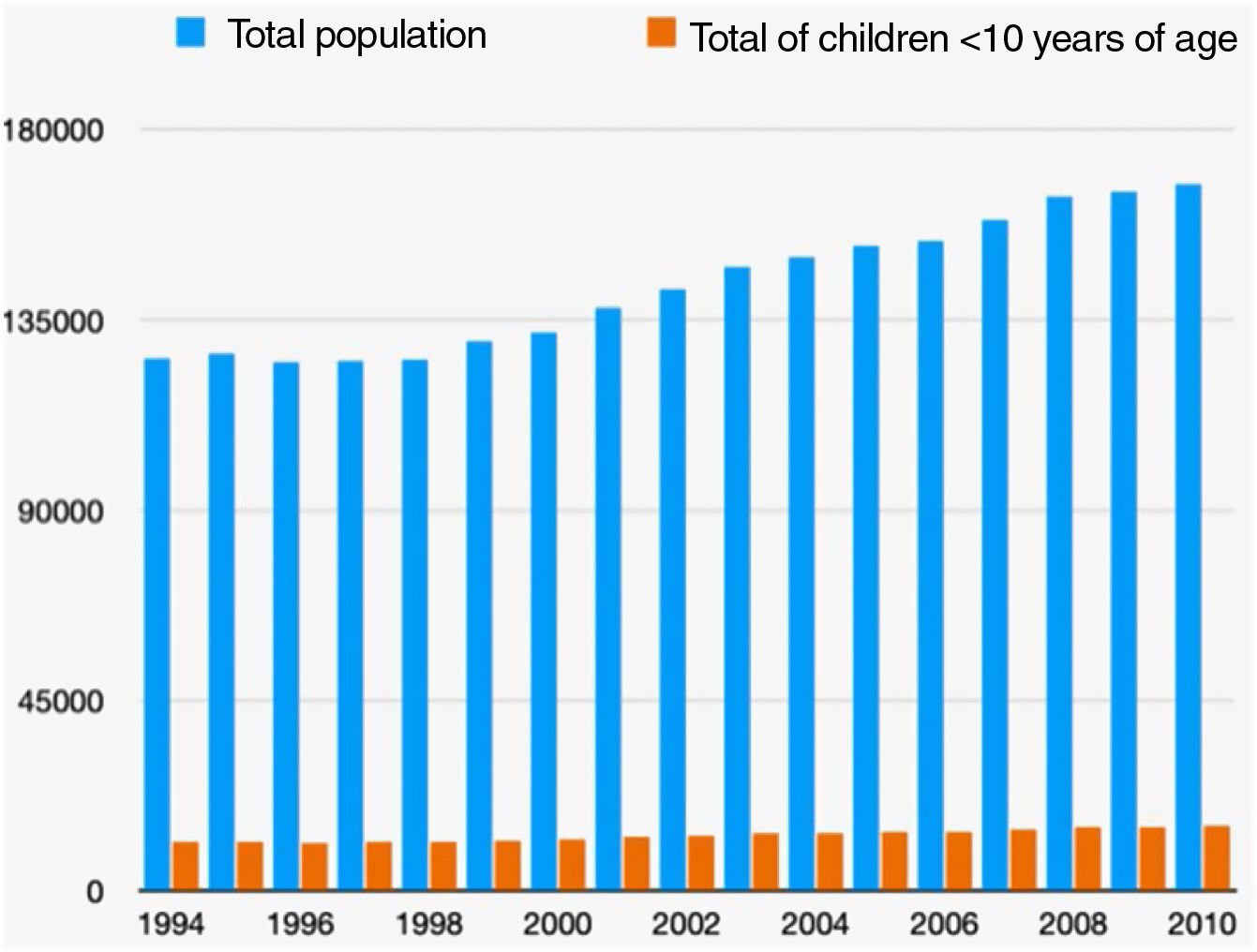

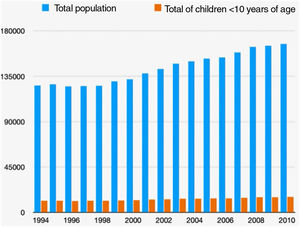

ResultsIn the following incidence data, the total population ranged from a low of 124,963 in 1996 to a high of 167,082 in 2010. Similarly, the population of children under 10 years of age ranged from a low of 11,409, also in 1996, to a high of 14,254 in 2010 (Fig. 2).

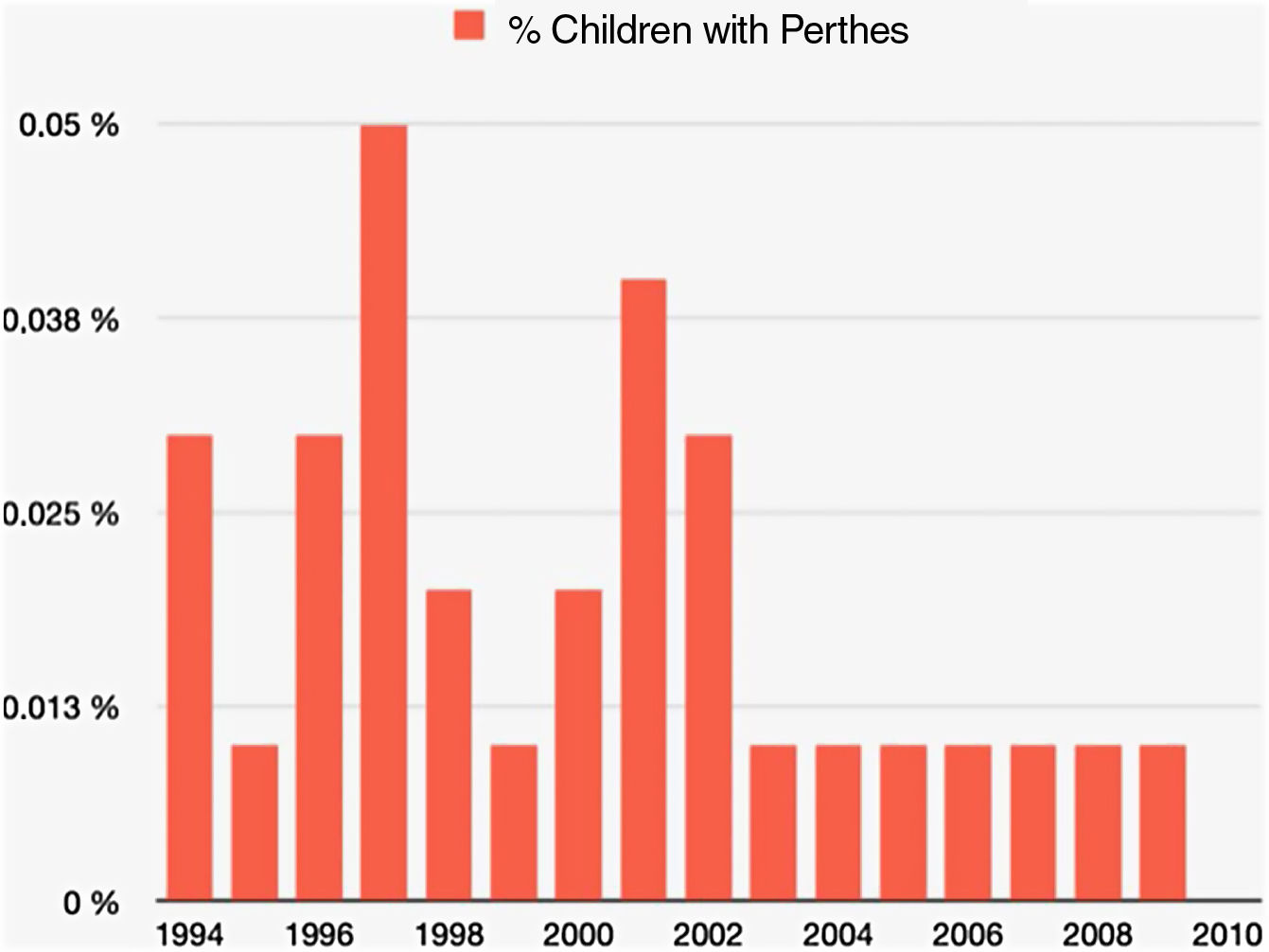

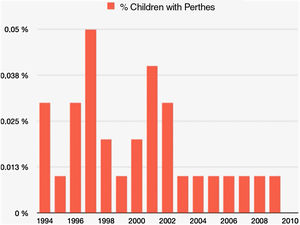

Children under 10 years of age accounted for 9.3% of the total. Of the total 878 cases of LCPD seen at the referral hospital, there were 40 cases between 1994 and 2010 that belonged to Health Area 2 of the Community of Madrid (Fig. 2). Of these, 22 patients came from Coslada, 6 from Mejorada del Campo, 11 from San Fernando de Henares and one from Velilla de San Antonio. The percentage of children with CDPL ranged from 0 to .04% (Fig. 3).

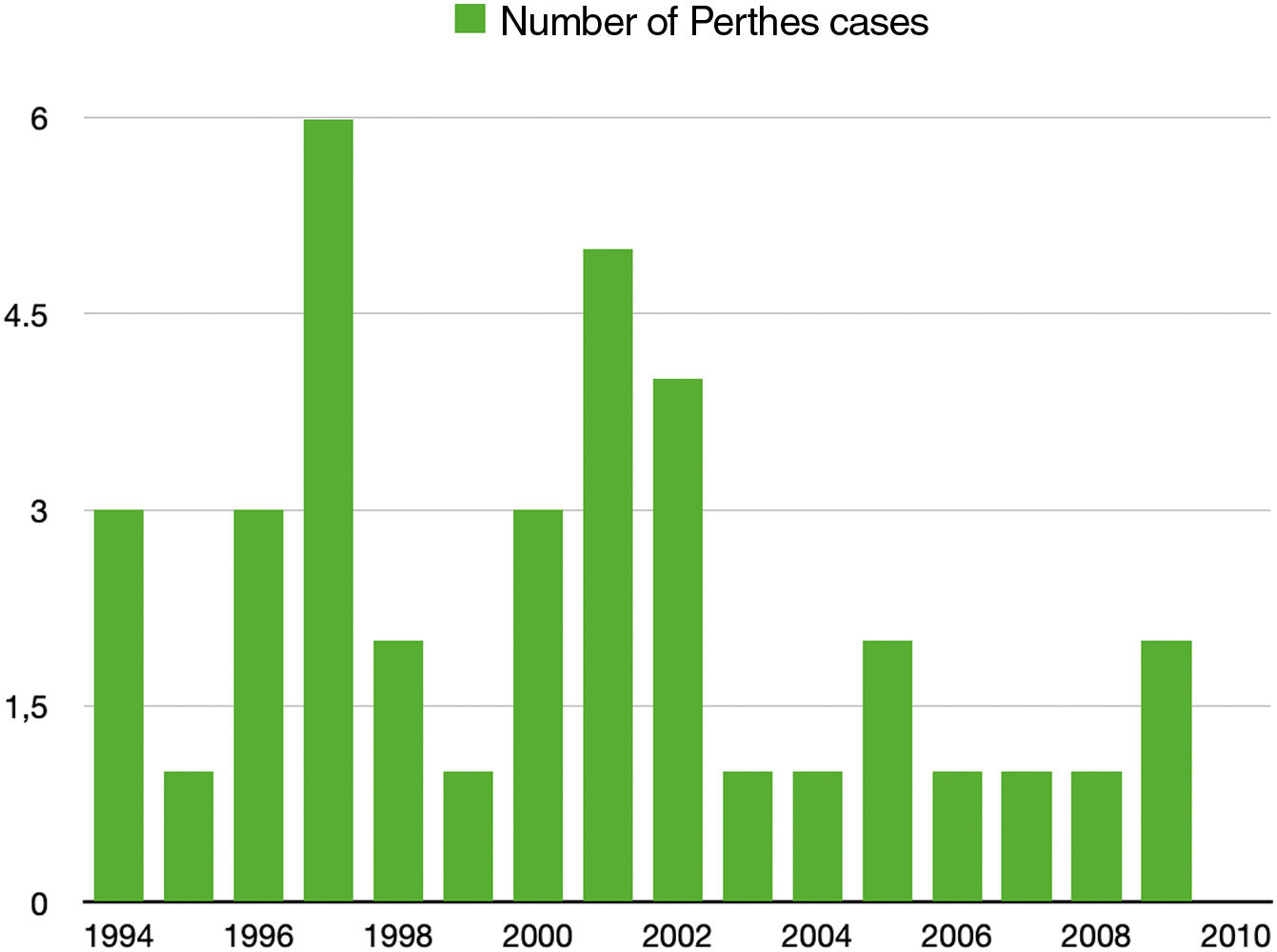

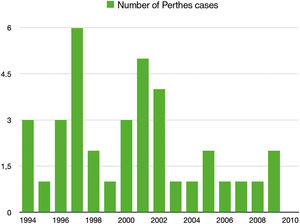

The incidence was 2.35 new cases per year, ranging from 0 to 6 cases in the period from 1994 to 2010 (Fig. 4).

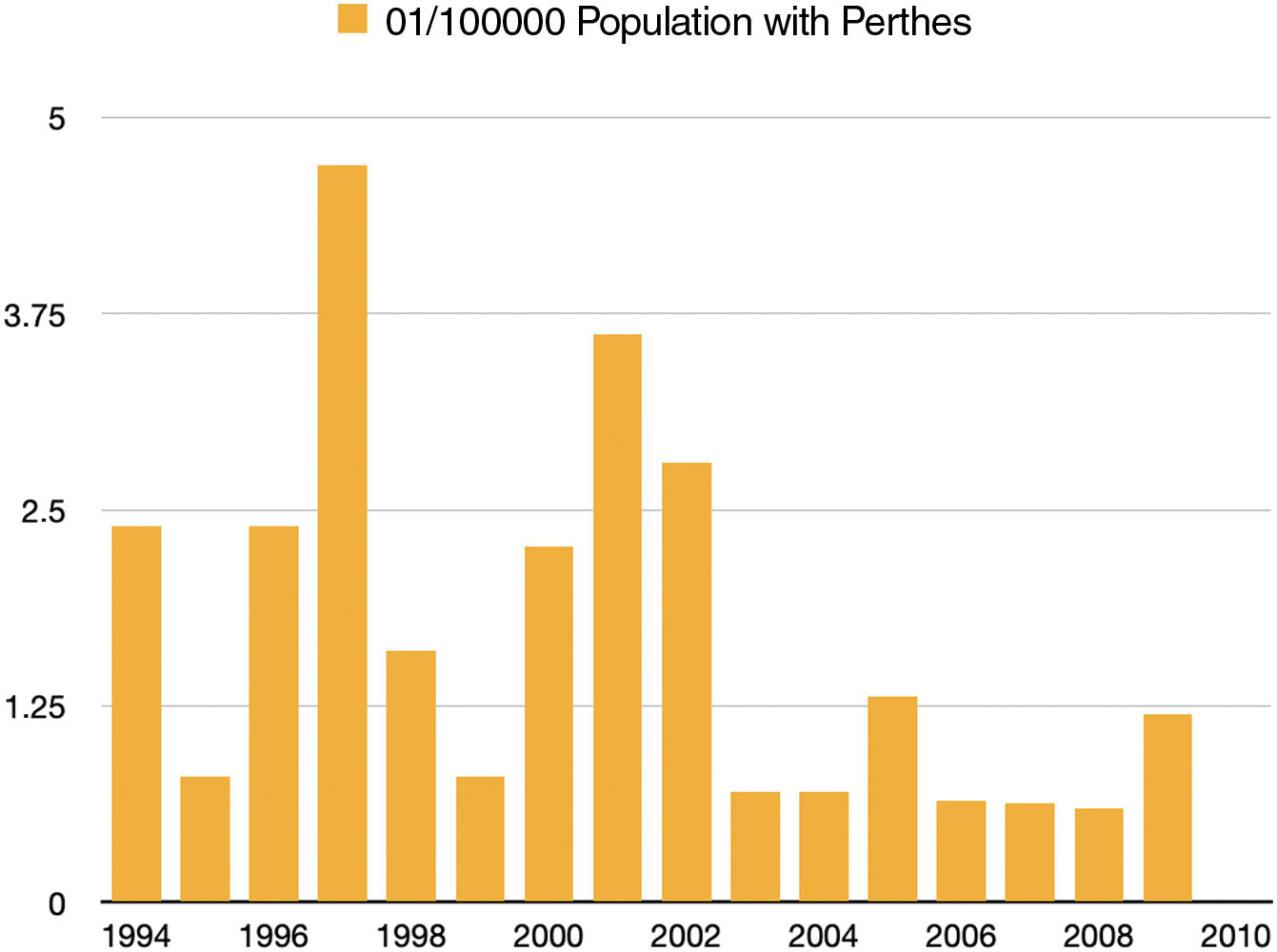

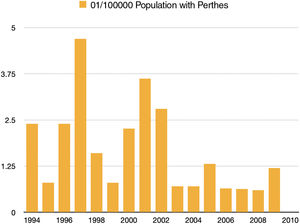

The mean annual incidence was 1.59 per 100,000 population over 21 years. But it varied between 0 and 4.7 per 100,000 population, depending on the different years (Fig. 5). The highest incidence of cases occurred in 1997, with 6 cases, and the lowest in 2010, when no new cases appeared. The highest number of cases was observed between 1994 and 2002, followed by a decrease until 2010. The mean number of new cases of LCPD decreased from 2.38 in the period 1994–2002 to 0.83 between 2003 and 2010. The frequency with respect to the population of children under 10 years of age was 2 new cases per 10,000 children (Table 1).

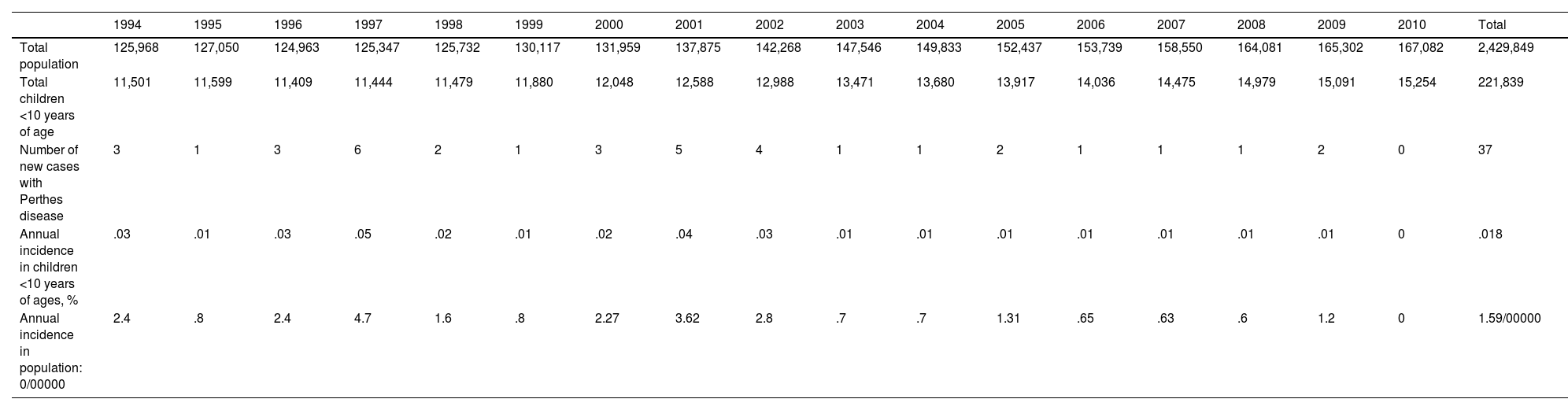

Data of incidence of the Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease in the Mediterranean health area.

| 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 125,968 | 127,050 | 124,963 | 125,347 | 125,732 | 130,117 | 131,959 | 137,875 | 142,268 | 147,546 | 149,833 | 152,437 | 153,739 | 158,550 | 164,081 | 165,302 | 167,082 | 2,429,849 |

| Total children <10 years of age | 11,501 | 11,599 | 11,409 | 11,444 | 11,479 | 11,880 | 12,048 | 12,588 | 12,988 | 13,471 | 13,680 | 13,917 | 14,036 | 14,475 | 14,979 | 15,091 | 15,254 | 221,839 |

| Number of new cases with Perthes disease | 3 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 37 |

| Annual incidence in children <10 years of ages, % | .03 | .01 | .03 | .05 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .04 | .03 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | 0 | .018 |

| Annual incidence in population: 0/00000 | 2.4 | .8 | 2.4 | 4.7 | 1.6 | .8 | 2.27 | 3.62 | 2.8 | .7 | .7 | 1.31 | .65 | .63 | .6 | 1.2 | 0 | 1.59/00000 |

Knowledge of the incidence of a disease in a health area is important for forecasting and adjusting population needs. Health resources must be based on detailed knowledge of the population's needs. An extensive literature search carried out by the authors has failed to find any publication that refers to the incidence of LCPD in Spain. It is a disease that requires long-term follow-up by paediatric orthopaedic specialists with the consequent consumption of resources, and, once cured, it can develop numerous sequelae, especially osteoarthritis of the hip, which again will consume resources in adult orthopaedic services. For all these reasons, it is important to know the number of patients that appear each year in a health area, in order to be able to extrapolate it to the rest of Spain, given its similar characteristics in terms of latitude, race and industrial development.

According to what has been published, it can be affirmed that the incidence is higher in the Caucasian race, to which we belong. This description would lead us to believe that the casuistry in our population area, which is predominantly Caucasian, will be high. However, in recent studies, it is latitude that is strongly associated with the incidence of the disease. It is even described that, within the same country, the incidence varies according to the area of residence and in relation to the urban or rural lifestyle. In the study by Rowe et al.,3 in Chonnam Province, Korea, the incidence is higher in rural than in urban areas. However, in the Caucasian populations studied by Hall et al.2 a higher number of cases are found in urban and lower social class populations. These socio-economic data are similar to those of our study and the type of population, an urban area of lower-middle socio-economic class. It is therefore thought that socioeconomic characteristics play an important role in the development of the disease. Children with LCPD have worse physical and social conditions than the rest of the child population. It seems that sufferers must be subjected to certain environmental factors years before the onset of the first symptoms.7

The incidence of LCPD in the Mediterranean population has hardly been studied to date and we have not found publications describing this incidence in the Spanish population or even in southern Europe. Our results show the incidence of LCPD in the Mediterranean area, closer to the equator than in Anglo-Saxon countries, but, at the same time, in an industrial population with similar characteristics to those studied there (Fig. 1). The greater similarity of incidence in our data with respect to the African population could be explained by the geographical location of our country, closer to the equator, although socioeconomically we have similarities with the Anglo-Saxon population.5,6 In short, the influence of latitude should be analysed bearing in mind socioeconomic factors and geographical location.

The results described in this study allow us to show the real incidence of LCPD in Health Area 2 of Madrid, as it is a very specific population, with little migration and high patient loyalty to the reference hospital. Thus, of the 40 cases studied, only one was lost to follow-up during the 17 years of the time interval studied. No flow of patients to private health care centres was observed, as this type of coverage was only available to approximately .5% of the reference population. Moreover, this small number of paediatric patients easily obtained referral to the public system once the diagnosis was made, as they did not have a referral hospital for children.

ConclusionsThe figures obtained are more similar to those found in studies that analyse populations close to the equator, despite the fact our area is a primarily industrial region similar to populations in the UK.

Larger studies may be needed and this basis could allow us to extrapolate the financial, material and human resource requirements for the detection and follow-up of this destructive process in children's hips.

Study limitationsDespite the power of statistical inference, as this is a study in a single area, there may be differences in incidence from a larger area, whether province or nation.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

FundingThe authors declare that they have received no funding for the conduct of the present research, the preparation of the article, or its publication.