The incidence of hip fracture in the elderly is on the rise, occasionally accompanied by concurrent upper limb fractures. Our investigation aims to determine whether these patients experience poorer functional outcomes, prolonged hospitalisation, or higher mortality rates when compared to those with isolated hip fracture.

Material and methodsWe retrospectively reviewed 1088 elderly patients admitted to our centre with hip fracture between January 2017 and March 2020. We recorded the presence of concomitant fractures and their treatment. We analysed the duration of hospital stay, in-hospital mortality and function.

ResultsWe identified 63 patients with concomitant upper limb fracture (5.6%). Among them, 93.7% were women, and the average age was 86.4 years. 80.9% of the upper limb fractures were distal radius or proximal humerus. Patients with concomitant fracture had increased length of stay (mean, 19.6 vs. 12.8, p=0.002), decreased proportion of patients returning to their own home at discharge (23.6% vs. 26.3%, p=0.042) and increased in-hospital mortality rate (9.5% vs. 5.9%, p=0.003).

ConclusionsPatients with concomitant upper limb fracture require a longer length of stay and exhibit an elevated in-hospital mortality rate. Furthermore, this condition is associated with a reduced short-term functional recovery, thereby decreasing the chances of the patient returning home upon hospital discharge.

La incidencia de las fracturas de cadera en los ancianos está en aumento, a veces acompañada de fracturas concomitantes en miembros superiores. Nuestro estudio tiene como objetivo determinar si estos pacientes experimentan peores resultados funcionales, una tasa de hospitalización más prolongada o tasas de mortalidad más elevadas en comparación con aquellos con fractura de cadera aislada.

Material y métodosRealizamos una revisión retrospectiva de 1.088 pacientes ancianos ingresados en nuestro centro con fractura de cadera, entre enero de 2017 y marzo de 2020. Registramos la presencia de fracturas concomitantes y su tratamiento. Analizamos la duración de la estancia hospitalaria, la mortalidad intrahospitalaria y la funcionalidad de los pacientes al alta.

ResultadosIdentificamos 63 pacientes con fractura concomitante de miembro superior (FCMS) (5,6%); de ellos, el 93,7% fueron mujeres y la media de edad fue de 86,4 años. El 80,9% de las FCMS fueron fracturas de radio distal o húmero proximal. Los pacientes con FCMS presentaron una mayor estancia hospitalaria (media, 19,6 vs. 12,8, p=0,002), una menor proporción de pacientes que se fueron de alta a su domicilio (23,6% vs. 26,3%, p=0,042) y una mayor tasa de mortalidad intrahospitalaria (9,5% vs. 5,9%, p=0,003).

ConclusiónLos pacientes con FCMS requieren una estancia hospitalaria más prolongada y presentan una tasa de mortalidad intrahospitalaria elevada. Además, esta condición se asocia con una reducida recuperación funcional a corto plazo, disminuyendo la probabilidad de que el paciente pueda regresar a su domicilio al alta hospitalaria.

Hip fractures in the elderly are derived from previously brittle bones and are therefore the result of low-energy mechanisms, most commonly falls from the person's own height. These fractures are one of the main health issues in this age group. In our country, the cost of caring for these fractures is 1.591billion euros per year. According to the National Hip Fracture Registry, the annual incidence is estimated to be 103.76 cases per 100,000inhabitants/year.1,2 A total of 7200 hip fractures were recorded for the year 2019 and this figure is expected to increase significantly in the coming years due to the progressive ageing of the population.2 These patients may simultaneously suffer a fracture of the upper limb, because of the fall itself and the individual's history of osteoporosis.3,4 This poses a challenge for functional recovery, since rehabilitation is more cumbersome and complex,5–7 potentially leading to a decline in these patients’ functional capacity and, as a consequence, in their prognosis and quality of life.8–12 The aim of our study was to explore and compare the clinical and functional outcomes of people in our centre who presented hip and concomitant upper limb fractures with fractures of the hip alone in patients over the age of 65 years sustained as a consequence of low-energy injuries.

Material and methodsWe conducted a retrospective cohort study of a series of 1088 subjects over 65 years of age, who were admitted to our centre with a diagnosis of hip fracture caused by a low-energy mechanism, during the period from January 2017 to March 2020. The patients were divided into two groups of individuals who presented with an associated concomitant fracture of the upper limb (63 cases) and those who sustained a hip fracture alone (1025 subjects).

The data analysed were obtained from our centre's medical records and from the National Hip Fracture Registry.

The main variables collected were the type of hip and upper extremity fracture, age, sex, time of admission, and in-hospital mortality. In addition, the place of residence of the person prior to the fracture and the place to which they were discharged, their ability to walk before the fracture, whether they required technical aids for walking, and their ability to walk one month following hospital discharge were likewise recorded.

The patients’ functional capacity was inferred from a comparison of their ability to walk prior to being admitted to hospital and then again, one month after discharge; the proportion of cases in which they could be discharged directly to their home from the hospital or those who, in contrast, had to be discharged to a rehabilitation centre or a nursing home where they could continue their functional recovery.10,13

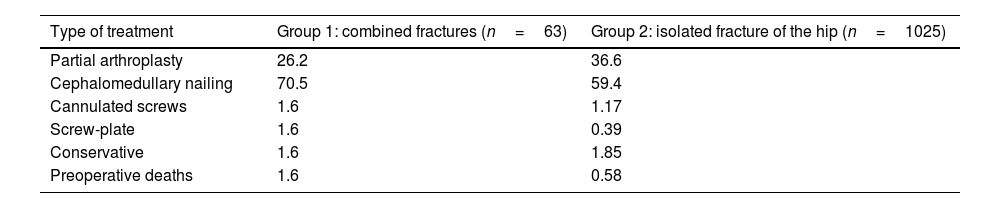

The hip fractures were classified as intra- or extracapsular fractures; in addition, the management of the hip fracture and the associated upper limb fracture was documented as conservative or surgical. All the subjects who had suffered an extracapsular fracture were treated with endomedullary nailing, while those with intracapsular fractures were treated according to the Garden I or II classification with conservative treatment or osteosynthesis using cannulated screws; Garden types III or IV fractures were surgically treated with hip arthroplasty.

As for the postoperative rehabilitation protocol, all patients were seen by the rehabilitation physician and physical therapists on the first day following surgery and initiated joint mobility exercises in bed and quadriceps isometrics, with early assisted walking if the individual's medical condition made this possible.

Statistical analysisThe statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software package, version 20.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA) and compared the variables between the two study groups with parametric tests for normally distributed variables (Pearson's Chi-square test for qualitative variables and Student's t-test and Anova for quantitative variables). Statistical significance was set at p<.05.

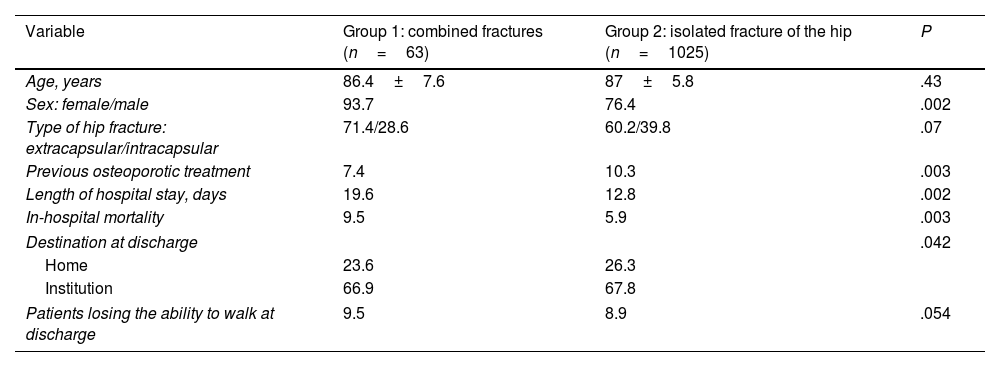

ResultsBetween January 2017 and March 2020, 1088 patients with a diagnosis of hip fracture were admitted to our centre. We identified 63 (5.6%) subjects who presented with a hip fracture associated with a concomitant fracture of the upper extremity (FCMS) and 1025 (94.4%) individuals who had a hip fracture in isolation. There were no statistically significant differences in terms of age between the groups (p=0.43) (Table 1).

Demographic and epidemiological data.

| Variable | Group 1: combined fractures (n=63) | Group 2: isolated fracture of the hip (n=1025) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 86.4±7.6 | 87±5.8 | .43 |

| Sex: female/male | 93.7 | 76.4 | .002 |

| Type of hip fracture: extracapsular/intracapsular | 71.4/28.6 | 60.2/39.8 | .07 |

| Previous osteoporotic treatment | 7.4 | 10.3 | .003 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 19.6 | 12.8 | .002 |

| In-hospital mortality | 9.5 | 5.9 | .003 |

| Destination at discharge | .042 | ||

| Home | 23.6 | 26.3 | |

| Institution | 66.9 | 67.8 | |

| Patients losing the ability to walk at discharge | 9.5 | 8.9 | .054 |

The most common site of concomitant upper limb fracture was the distal radius, which was found in 31 people (49.2%), followed by the proximal humerus, which was detected in 20 cases (31.7%). Other less frequent fracture sites were the olecranon, clavicle, or distal humerus, accounting for 19.1% of the patients.

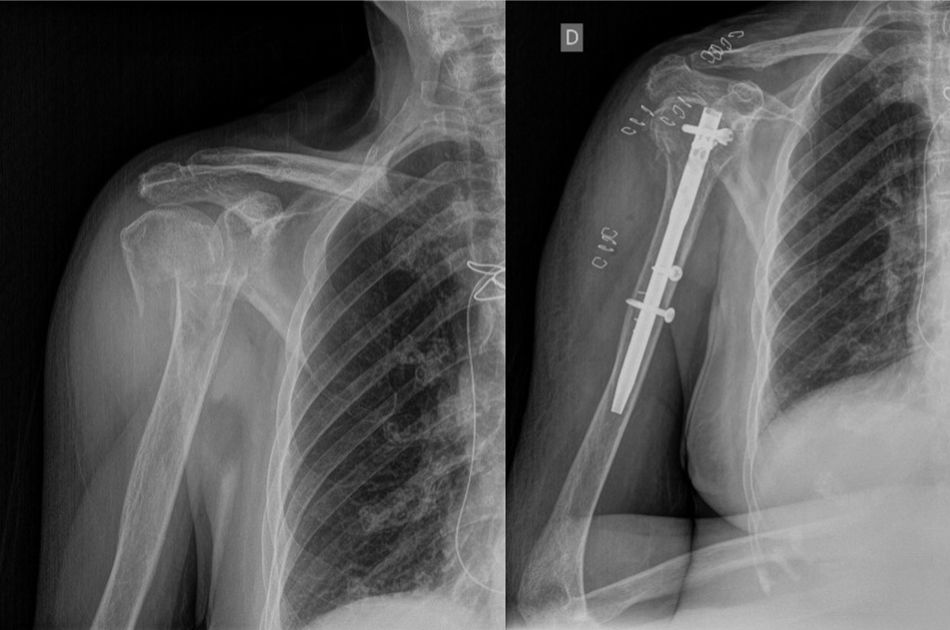

Inasmuch as the type of hip fracture is concerned, the distribution of intracapsular fractures among the people in the FCMS group relative to the group of cases of isolated hip fracture was 28.6% vs. 39.8%, while extracapsular fractures displayed a distribution of 71.4% vs. 60.2%, respectively (Fig. 1; Table 2).

Of the subjects with FCMS, 8.1% (5/63) underwent surgery to treat their upper limb fracture, while 91.9% (58/63) were managed conservatively (Fig. 2).

A higher proportion of females to males was noted in both groups. In the FCMS group, the percentage of women was 93.7%, while in the isolated hip fracture group they comprised 76.4% of the total number of cases.

Prior to sustaining the fracture, 10.3% of the individuals with an isolated hip fracture had been taking some kind of treatment for osteoporosis (antiresorptive or osteoforming agents). On the other hand, only 7.4% of the patients who experienced an associated FCMS had been prescribed such treatment (10.5% vs. 7.4%, p=0.003).

The mean in-patient stay in the isolated hip fracture group was 12.8 days, while in the FCMS group it was 19.6 days (p=0.002).

In terms of destination at the time of hospital discharge, the percentage of people who returned home was statistically significantly lower in the concomitant fracture group than in the isolated fracture group (26.3% vs. 23.8%, p=0.042).

Of the total number of subjects who were able to walk before suffering the fracture, 9.5% of the individuals with FCMS had ceased to walk on their own one month after being released, from the hospital discharge, as opposed to 8.9% of those who had sustained a hip fracture alone (p=0.054).

With regard to mortality, 9.5% of the people in the FCMS group passed away while in the hospital (6/63), whereas there was a 5.9% mortality rate in the isolated fracture group (60/1025) (p=0.003).

DiscussionFCMS associated with hip fractures are a common health problem in the elderly with bone fragility. Mulhall et al. report that 4.7% of all patients with hip fracture present a concomitant fracture of the upper limb.5 Since then, numerous studies have documented similar prevalence rates, ranging from 4% to 6.5%.9,13,14 The results of these works concur with the findings noted in our series (5.6%).

In both study groups, females outnumber males. The authors of previously published studies state that there is a statistically significant higher percentage of women with concomitant fracture of the upper limb associated with hip fracture (84.7% vs. 73.2%, p<0.001).4,13 Likewise, there is a greater percentage of females with concomitant fractures in our series; this difference is statistically significant (93.7% vs. 76.4%, p<0.001).

Meanwhile, Kang et al. found that the subjects with an isolated hip fracture were older than those with FCMS (79.3 vs. 75.9, p=0.001).4 In contrast, however, Tow et al. state that the patients who presented concomitant fracture of the upper limb were older (mean age of 78 vs. 79.5 years).10 Other more recently published studies, such as the one by Morris et al. have failed to establish statistically significant differences in terms of mean age.13 Our research corroborates the findings of Morris et al. and finds no statistically significant intergroup difference between the two groups studied (86.4 vs. 87 years, p>0.05).13

For the most part, concomitant fractures of the upper limb tend to involve fractures of the distal radius and of the proximal humerus.4,5,9,14,15 In our series, the results obtained are consistent with those of other studies in the literature: 81% of the upper extremity fractures occurred in the distal radius and proximal humerus.

The vast majority of the FCMS from our series were treated conservatively (91.9%) and had a negative impact on patient mortality and length of hospital stay, in line with other publications4,6,13,16–21; nevertheless, Buecking et al. treated FCMS surgically in a larger percentage of their subjects (56%) and their series reflected no increase in duration of hospitalisation (14 vs. 14 days, p=0.799) or mortality rate (9.5% vs. 5.9%, p=.003) in their cases of FCMS.17 Lee et al. observed no significant differences in mortality or hospital stay in people with concomitant upper extremity fractures of either the distal radius or proximal humerus, albeit they did observe better functional outcomes among individuals who suffered an associated fracture of the distal radius as opposed to the proximal humerus.22 Ganta et al. compared cases of concomitant proximal humerus fractures that underwent conservative vs. surgical treatment, and found no significant differences with respect to length of hospitalisation or destination at discharge. They indicate that a greater proportion of patients return to their former functional status; however, this difference has not reached the level of statistical significance (70% vs. 52%, p=.342).23 Therefore, one should contemplate the possibility that patients with a hip fracture and FCMS might benefit from surgical treatment of the upper limb injury, despite the fact that in other circumstances, this fracture would warrant conservative treatment.

In their study, Morris et al. reveal that presenting an associated upper extremity fracture lessens the possibility of the person being discharged to their own home (49% vs. 38.8%, p=0.001).13 Furthermore, Kim et al. also report a decreased likelihood of being discharged to their own home in the group with concomitant upper limb fractures (odds ratio [OR]=0.64, 95% CI 0.52–0.80, p<0.001).20 In their analysis by subgroups, it is worth noting that fractures of the distal extremity of the radius did not significantly lower the possibility of discharge to their own home (p=0.082), with fractures of the proximal extremity of the humerus causing this decrease (p=0.001) and, as a result, the difference between groups.13 While it is true that in our series we also observed that presenting a FCMS decreases the chances of the individual being discharged to their home (23.8 vs. 26.6%, p=0.042), we detected no statistically significant differences in the type of FCMS and the patient's discharge destination, with fractures of the distal radius and those of the proximal humerus entailing a similar impact. Other authors, such as Gómez-Álvarez et al. also found that the proportion of cases referred to a functional support centre in the FCMS group is higher than those in the isolated hip fracture group (p=.03).15

Tow et al. compared 33 subjects with FCMS and another 33 who had an isolated hip fracture and discovered that 36% of the participants with FCMS were able to walk at discharge, in contrast to 64% of the group of individuals with only a hip fracture (p=0.05).10 In our cohort, of the total number of patients who had been walking prior to the fracture, 9.5% of those with a concomitant upper limb fracture had ceased walking at one month following discharge, compared to 8.9% of those who had an isolated hip fracture (p<0.05).

A number of publications have reported that in-hospital mortality is higher in the group of patients with an associated upper limb fracture than in the group who have an isolated hip fracture.15 We observed that in-hospital mortality in our series was 9.5% in the FCMS group and 5.9% in the isolated hip fracture group, and this difference was statistically significant (p=0.003), which is consistent with previously published studies. The mortality rate recorded in our series endorses the findings of Morris et al. in their study, in which 8.1% of the patients with FCMS died.13 However, contrary to these results, other authors have documented no statistically significant differences in mortality rates between the group of people who had an associated FCMS and the ones who had a hip fracture alone.17,19

ConclusionPatients with FCMS require longer hospital stays and suffer increased in-hospital mortality, as well as worse short-term functional recovery, a greater percentage of individuals who no longer walk, as well as a decreased likelihood that the person will be able to return home after being discharged from the hospital.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Ethics approvalThis work was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Clínico San Carlos.

FundingThe authors of the present work have not received any kind of funding.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.