Arthroscopic tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis with a retrograde nail is performed as a minimally invasive technique in patients without improvement in conservative treatment of osteoarthritis. Complications and hospital stay after surgery are less using this technique when they are compared with open ones.

Materials and methodsWe review retrospectively from 2016 to 2019 seven patients subjected to a posterior arthroscopic tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis with a retrograde intramedullary nail. AOFAS scale was used to assess functional results and we collected other data as complications, time required for bony union, time of nonweight-bearing and scale of satisfaction. We also made a description of the technique we performed.

ResultsThe mean hospital stay was 3.43±0.53 days, patients have well functional results and complications were very low. It was noticed tibiotalar bony union in about 86% of patients 10 weeks after surgery and subtalar bony union in about 71% 20 weeks after surgery. Nonweight-bearing was made using a cast for 4 weeks and later, it was changed for Walker allowing patients partial weight-bearing until 10 weeks after surgery. One patient had wound complications and he needed later surgery and another presented tibiotalar pseudoarthrosis, although without symptoms.

ConclusionPosterior arthroscopic tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis offers very good results with a high rate of bony union, few complications, and minimal nonweight-bearing time. This technique could be used in patients without major deformities, especially in those at high risk of complications from the surgical wound.

La artrodesis tibiotalocalcánea artroscópica con clavo retrógrado es una técnica mínimamente invasiva que se realiza en pacientes con artrosis que no mejoran con tratamiento conservador. La ventaja de esta técnica es su menor estancia hospitalaria y su menor tasa de complicaciones respecto a técnicas abiertas.

Materiales y métodosSe realiza un estudio retrospectivo descriptivo de los 7 pacientes intervenidos, entre 2016 y 2019, de artrodesis tibiotalocalcánea artroscópica por vía posterior con clavo retrógrado en nuestro hospital. En él se analizan los datos de funcionalidad con la escala AOFAS, el grado de satisfacción, el tiempo de consolidación, de descarga y las complicaciones. Además, se realiza una descripción de la técnica quirúrgica empleada.

ResultadosSe observaron una estancia hospitalaria de 3,43±0,53 días de media, buena funcionalidad y baja tasa de complicaciones. Obtuvimos consolidación tibiotalar en el 86% de los casos en aproximadamente 10 semanas y una consolidación subtalar en el 71% en 20 semanas. El tiempo de descarga fue de 4 semanas con férula y posteriormente carga parcial con Walker hasta la décima semana postoperatoria. Uno de los casos tuvo que ser reintervenido por complicaciones en la herida quirúrgica y otro presentó seudoartrosis tibiotalar, aunque sin repercusión clínica.

ConclusiónLa panartrodesis artroscópica por vía posterior ofrece muy buenos resultados, con elevada tasa de consolidación ósea, pocas complicaciones y tiempo de descarga mínimo. Esta técnica podría ser utilizada en pacientes sin grandes deformidades, sobre todo en aquellos con alto riesgo de complicaciones de la herida quirúrgica, al constatarse un descenso de las mismas.

Tibiotalocalcaneal (TTC) arthrodesis has been performed for over 50 years1 on patients with osteoarthritis at this level who have not improved with other treatments. Since then, the technique has notably developed and it is a treatment option in patients with osteoarthritis of the ankle, and also in the subtalar joint which does not respond to medical treatment. It is indicated in primary osteoarthritis, post-traumatic diseases and neurological and inflammatory deformities, among others.

Different methods have been described in the literature to achieve a satisfactory joint fusion, either using plates, screws, pins, or external fixators. Open techniques were used as standard but in recent years minimally invasive techniques, such as arthroscopic, have been developed with favourable results.2

The development of less invasive techniques is highly useful in patients with cutaneous and vascular diseases and in changes to wound healing, with perioperative complications derived from major open approaches able to be reduced.

Arthroscopy-assisted arthrodesis presents with comparatively fewer comorbidities than the open techniques and reduced hospital stay.2 In addition, endomedullary interlocking arthrodesis offers the added benefit of less soft tissue injury and a more rigid internal fixation, which allows for a more rigid loading of the joint, leading to early weight-bearing.3

Due to these results we decided to assess the efficacy of arthrodesis achieved with the arthroscopic technique and endomedullary interlocking, together with the possible complications and benefits of the method used.

The aim of our study was to add the cases of posterior arthroscopic TTC performed in our department to the few cases already described in the literature and to compare the clinical and functional results obtained to confirm its benefits.

Material and methodsA descriptive, retrospective case study was conducted which included all patients operated on between 2016 and 2019 with arthroscopic TCC arthrodesis, with a minimum of one year follow-up. Patients who underwent operations in other years and patients who did not meet with the follow-up period were excluded from the study.

Prior to surgery the following variables were collected: age, sex, arthropathy aetiology and hindfoot axis and its degrees, the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society scale (AOFAS), and presurgical haemoglobin. In addition, the need for fibula osteotomy, ischaemia and surgery time were documented during the operation. Also, postoperative data such as haemoglobin and the need for postoperative transfusion, postoperative alignment, partial and total unloading time, satisfactory arthrodesis at both tibiotalar and subtalar levels, and complications either perioperatively or during follow-up were recorded.

During follow-up the AOFAS scale was used after one month, after 3 months, after 6 months and after 12 months, and satisfaction was measured by asking if the patient would repeat the operation. Lastly, approximately between 12 and 18 months after surgery a computerised tomography (CT) scan was performed in 5 of the 7 patients to confirm whether or not there was tibiotalar and subtalar consolidation. In patients where no CT scan was performed and consolidation was not observed, posterior radiographies were reviewed up until 31st December 2020 in search of joint fusion signs.

To create the database a list of patients who had undergone arthrodesis up until 31st December 2019 was used and patients who did not meet with inclusion criteria were excluded, obtaining a list of 7 patients whose histories were reviewed retrospectively.

Data were subsequently exported to the SPSS programme for statistical analysis of the variables. For quantitative variables the “normality” of their distribution was initially confirmed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. If the variable approximated the Gaussian distribution the mean and standard deviation and median were calculated, and otherwise the 25th and 75th percentiles were calculated. In the qualitative variables the absolute frequency and percentage of each category were shown.

Lastly, the Wilcoxon test was used to observe the statistically significant differences in measuring of the AOFAS scale over time and the pre and postoperative haemoglobin rates.

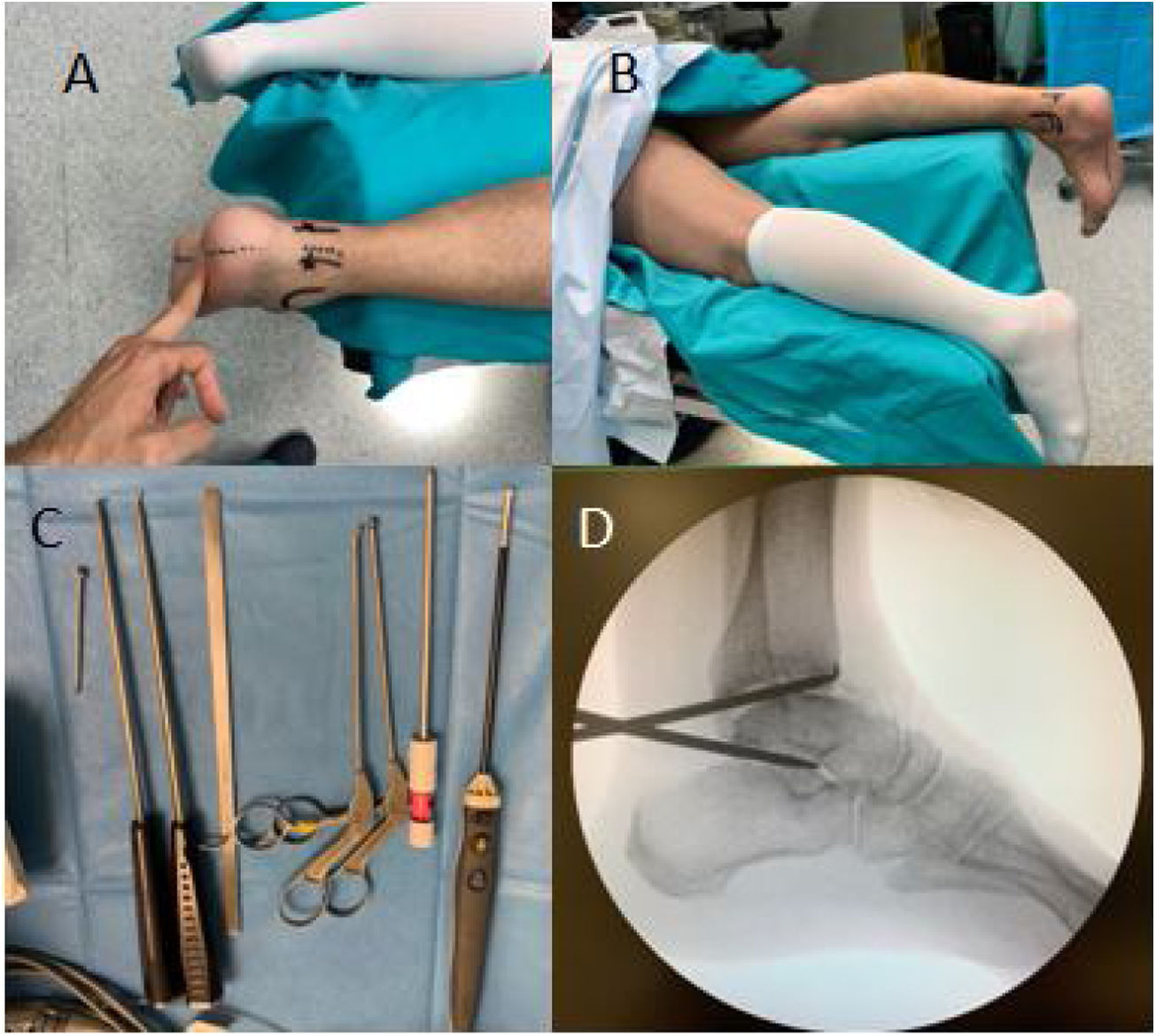

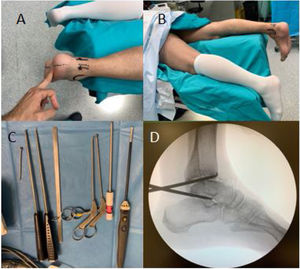

Description of the surgical technique and postoperative managementThe patient is placed in prone position on a soft support with an ischaemia cuff (Fig. 1). Posterior arthroscopic portals are used, both posterolateral and posteromedial, as described by Van Dick.4 Firstly, the posterolateral portal (parakle) is entered 1cm proximal to the distal tip of the external malleolus, through which the 4.5mm arthroscope is introduced, allowing an oblique view of up to 30° entering the tibiotalar joint, heading towards the second metatarsal. Then, through the direct view of the optics, the posteromedial portal is made at the same height as the previous one, to introduce the instruments.

Intraoperative images of the posterior arthroscopic technique. (A and B) Prone position of the patient with the ankle protruding distally to the operating table and on a soft support and anatomical references for posterior arthroscopic portals. (C) Arthroscopic instruments used with 4.5mm arthroscope with 30. (D) Intraoperative lateral X-ray showing excellent access to the tibiotalar and subtalar joints.

The ankle should be kept in a neutral position to facilitate orientation, using the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) as a reference, as it represents the limit of resection in the medial part of the joint, and can act lateral to it as it constitutes a safety area to protect the posterior tibial vasculonervous bundle at 6.8mm from it.5,6 Using a synoviotome and/or a vaporiser from the posteromedial portal, the ligament of Rouviere and Canela, the intermalleolar ligament and the posteroinferior tibiofibular ligament are resected. Next, the tibiotalar and posterior subtalar joint surfaces are reamed 1–2mm to a bleeding area using a 4mm high-speed reamer. The safety area should be visualised at all times to avoid vasculonervous injury.7 A fibula osteotomy is then performed to improve tibiotalar compression, favouring subsequent consolidation.

The final ankle arthrodesis position to be obtained is a neutral foot in the sagittal plane, external rotation of 5° with respect to the tibia and 0–5° hindfoot valgus.8 It is important to maintain this position because excessive dorsiflexion can cause thalgias, while increased plantar flexion can cause metatarsalgias or genu recurvatum.

Then, using the usual technique, the locked locking nail is inserted via the plantar route. Finally, the skin is closed and a sterile dressing and foot splint is applied. On discharge, the surgical wound is checked periodically on the 7th and 14th postoperative days, the latter being when the stitches are removed. In the postoperative follow-up, the splint is changed for a non-articulated Walker type boot on the 4th week after surgery, allowing partial loading with crutches with this one. This orthosis is removed at 12 weeks, without allowing full weight bearing without a Walker type boot until radiological images are obtained showing signs of bone consolidation.

ResultsThe sample studied comprised 7 cases, of which 85% were male, with a mean age of 65.43±9.39 years (Table 1). A normality study was performed observing that only the age variable was adjusted to said distribution. Approximately 57.1% of patients had undergone previous operations on these ankles, with osteosynthesis and extraction of osteosynthesis material (EOM) in post-traumatic cases and arthroscopic synovectomy in the remaining cases.

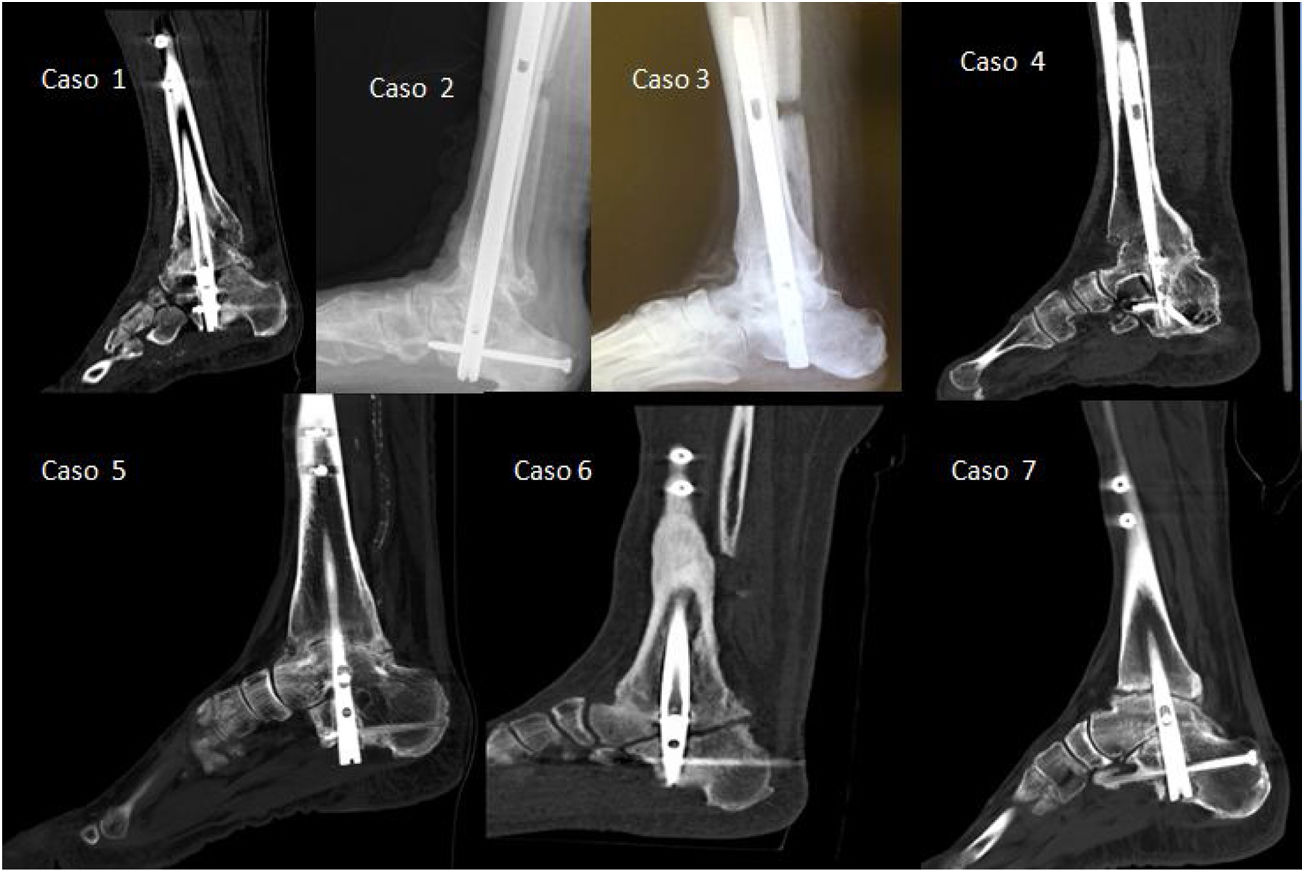

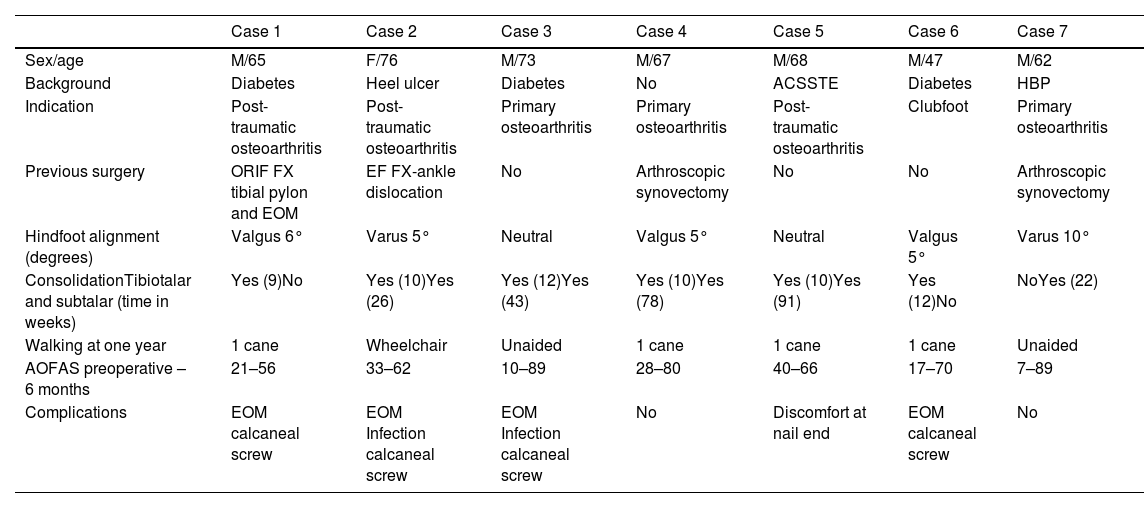

Summary of the cases of our study with background information, gait type at one year, AOFAS pre-surgery and 6 months after surgery, time of tibiotalar and subtalar joint consolidation and complications.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 | Case 5 | Case 6 | Case 7 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex/age | M/65 | F/76 | M/73 | M/67 | M/68 | M/47 | M/62 |

| Background | Diabetes | Heel ulcer | Diabetes | No | ACSSTE | Diabetes | HBP |

| Indication | Post-traumatic osteoarthritis | Post-traumatic osteoarthritis | Primary osteoarthritis | Primary osteoarthritis | Post-traumatic osteoarthritis | Clubfoot | Primary osteoarthritis |

| Previous surgery | ORIF FX tibial pylon and EOM | EF FX-ankle dislocation | No | Arthroscopic synovectomy | No | No | Arthroscopic synovectomy |

| Hindfoot alignment (degrees) | Valgus 6° | Varus 5° | Neutral | Valgus 5° | Neutral | Valgus 5° | Varus 10° |

| ConsolidationTibiotalar and subtalar (time in weeks) | Yes (9)No | Yes (10)Yes (26) | Yes (12)Yes (43) | Yes (10)Yes (78) | Yes (10)Yes (91) | Yes (12)No | NoYes (22) |

| Walking at one year | 1 cane | Wheelchair | Unaided | 1 cane | 1 cane | 1 cane | Unaided |

| AOFAS preoperative – 6 months | 21–56 | 33–62 | 10–89 | 28–80 | 40–66 | 17–70 | 7–89 |

| Complications | EOM calcaneal screw | EOM Infection calcaneal screw | EOM Infection calcaneal screw | No | Discomfort at nail end | EOM calcaneal screw | No |

ACSSTE: acute coronary syndrome with ST elevation; AOFAS: American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society; EF: external fixator; EOM: extraction of osteosynthesis material; FX: fracture; F: female; HBP: high blood pressure; M: male; ORIF: open reduction and internal fixation.

All cases were operated under spinal anaesthesia and the median ischaemia time was 2h. The median haemoglobin before surgery was 14.8g/dl (12.6–15.2) and afterwards 11.1g/dl (10.67–12.62), with no transfusions required in any of the cases. When the Wilcoxon test was used to compare the pre- and post-surgical haemoglobin medians, no statistically significant results were obtained with p=.48. The mean length of hospital stay was 3.43±.53days.

Follow-up data showed a median splint weight-bearing time of 4 weeks (4–6) after surgery; this was subsequently exchanged for a partially weight-bearing Walker boot for a median of 10 weeks (8–12). The median tibiotalar healing time measured on radiography was 10 (10–12) weeks and that of the subtalar joint was 43 (24–84.5), being mainly on the posterior aspect. Two cases of pseudoarthrosis of the subtalar joint were observed during the follow-up time (2.5 and 4 years respectively) (Fig. 2).

In terms of minor complications, the following were observed: discomfort of the osteosynthesis material, superficial infection and pseudoarthrosis at the subtalar level. The discomfort of the osteosynthesis material was due to the posteroanterior calcaneal screw in 4 of the patients, although one of them presented discomfort in the plantar area of the nail tip, with an excess length of the nail, without the need to remove it. In the case of superficial infection, only one of the patients presented with this complication, requiring debridement and antibiotic treatment with subsequent cures. As for subtalar pseudoarthrosis, only 2 cases were found, with no clinical repercussions.

Serious complications included one case of deep wound infection and another case of tibiotalar pseudoarthrosis.

The median preoperative AOFAS was 21 (10–33), at 1 month after surgery 50 (48–61), at 3 months 66 (62–80) and at 6 months 66 (61–89). Pre-surgical results were compared with those obtained at 1, 3 and 6 months, with no statistically significant differences, with p=.18 in all cases.

All patients, with the exception of one, were satisfied with the procedure and had neutral hindfoot alignment. They had plantigrade support and only 29% had mild metatarsalgia one year after surgery.

DiscussionArthroscopic fusion of the tibiotalar and subtalar joints has gained in popularity in recent years due to its minimal skin and soft tissue damage and low risk of neurovascular injury.3 TTC arthrodesis by intramedullary nailing provides excellent biomechanical stability and minimal soft tissue damage.9

Our work confirms the results of other studies comparing the use of arthroscopy with open approaches, showing a short hospital stay, less need for transfusions and good wound healing.10,11 These studies also found a lower complication rate, less perioperative pain and good functional outcomes with these minimally invasive arthroscopic approaches, as well as fewer reoperations and fewer wound complications. Despite this, the poor quality of the studies does not allow us to conclude the superiority of one technique over another. On the other hand, most of these studies use another fixation method such as cannulated screws to perform the arthrodesis and are therefore not very comparable with our work when it comes to functionality and fixation rates and times.

In our study, after surgery, a 4-week full weight-bearing time with splinting (4–6) and a partial weight-bearing time with a Walker boot until approximately week 10 (8–12) were performed. In the study by Baumman et al.,12 a total weight-bearing time of 8 weeks and the start of the Walker at 12 weeks was performed. Comparing the two studies, we found an average of less splint immobilisation and similar or less Walker weight-bearing. They obtained a pseudarthrosis rate of 33% of their patients, however, this could be explained by patients with complex diseases such as Charcot neuropathies and comorbidities. In contrast, we found only one case of pseudarthrosis (14%).

The systematic review by Franceschi et al.1 describes the results of several studies of arthrodesis using an intramedullary nail, all of which showed an 80% success rate of fixation in the tibiotalar joint with a mean time of 11–16 weeks. This confirms our results with arthroscopy, with 86% of cases consolidating at the tibiotalar joint in a mean time of 10 weeks (10–12) (Fig. 3).

Imaging tests of all cases at one to one and a half years post-surgery. In cases 2 and 3 only the lateral radiographs are shown as CT scans were not available; in the remaining cases, the longitudinal slices of the CT scans are shown to confirm the consolidation or absence of consolidation of the tibiotalar and subtalar joint.

Despite these good results in the tibiotalar joint, our work showed a 71% consolidation rate in the subtalar joint, especially in the posterior aspect and with a mean time of 43 weeks (24–84.5). These data were subsequently confirmed by CT scan 12–18 months after surgery in most cases. However, all our patients were asymptomatic after surgery. Other studies of intramedullary nail arthrodesis showed a similar rate of healing in this joint (74%), but less than that obtained in the tibiotalar joint, at approximately 20 weeks. They explained these results by the lack of compression, the design of the nail used and by not reaming the joint at this level.13 With our technique, subtalar joint reaming is performed, and the nail used would allow compression at this level.

However, if we compare our study with studies that use a similar technique to ours3,6,8,14 higher results than those described are observed in the consolidation of the subtalar joint, up to 80%. Despite this, studies such as that of Navarrete et al.14 show us results in this joint which are highly similar to 2 of their 5 cases with pseudo-osteoarthritis in the tibiotalar joint.

A review of the literature shows a serious complication rate of up to 45% following open ankle and subtalar arthrodesis, including: surgical wound dehiscence, deep infection, tibiotalar pseudarthrosis or failure of the fixation system.15 This rate decreases when minimally invasive procedures are performed, either through minimal approaches or arthroscopically.3,16

Our study confirms this hypothesis by maintaining a low rate of serious complications (28%), with one case of deep infection, which required surgical debridement and skin flap by plastic surgery, and one case of tibiotalar pseudoarthrosis. Despite these results, it should be noted that in the case of the deep infection, the patient presented with mesenteric ischaemia as a general complication in the postoperative period, which required surgical intervention by the General Surgery Service, resulting in significant clinical deterioration, the appearance of a decubitus ulcer on the heel and its superinfection by gram-negative germs. In relation to the case with tibiotalar pseudoarthrosis, it is important to emphasise that the patient was asymptomatic during the follow-up period.

In terms of functional outcomes, our study showed an improvement in AOFAS over the months, although there were no statistically significant differences in the comparisons. This is probably due to the low sample size. Nevertheless, we confirm the results obtained in other studies, such as that of Baumbach et al.,2,3 in which the functionality of the ankle is improved and pain is reduced with the use of arthroscopic methods.

Given the results of this study and the review of the literature, we conclude that the intervention described in this article could be used in certain types of patients with skin and soft tissue involvement, neuropathies, multiple previous surgeries or dermopathies due to medical diseases to avoid skin complications. In addition, our study has confirmed the reduction of peri- and postoperative bleeding, reducing the need for transfusions.

The technique described is easily reproducible for experienced surgeons, but for those less familiar with the use of the arthroscope and ankle arthroscopy it will require a learning curve. Furthermore, it is important to emphasise that the open technique should not be forgotten, as it is the option to be used in cases where arthroscopy is not possible or where intraoperative difficulties are encountered that prevent it from being performed. Nevertheless, our technique offers excellent access and visualisation of the posterior compartment of the ankle joint. By introducing the optics through the posterolateral portal, and using the posteromedial portal for instrument insertion, there is hardly any risk of damage to the neurovascular bundle.5 Following the described steps, posterior ankle arthroscopy is a safe and reliable method for performing TCC arthrodesis. In our experience, no cases of neuroapraxia of the sural or posterior tibial nerve have been described. None of the studies found performing such portals have demonstrated complications of this type of arthrodesis.3,6,8,14

The cases described in the literature are limited to cases without major varus/valgus deformities of the hindfoot, usually primary surgeries and without ankle dexasation. In these cases with large deformities, the use of an arthroscope to perform arthrodesis has not been compared with open surgery.2 This could lead to a bias when recommending the generalised use of arthroscopy for TCC arthrodesis, and for this reason its use should not be recommended in cases with large angular deviations that require greater visualisation and in which the anatomy is altered until it is studied. For all these reasons, we agree with previous studies and recommend open surgery in patients with marked deformity in the sagittal or coronal plane, significant ankle dexasations, previous surgeries where osteosynthesis material must be removed, or angulations>10° in cavus hindfoot.8,14 However, one of our cases had a varus angulation of 10° and showed good results, so this contraindication could change over the years.

Our study also has a number of limitations, as it has a very small sample size, preventing the use of parametric tests in the statistical analysis and, in addition, the data are analysed retrospectively, thus losing the level of evidence. Despite this, good results are obtained and can serve as a basis for a meta-analysis, together with studies that present a similar technique, with greater evidence. We recommend further studies in more complex cases to increase the indication for arthroscopy and to obtain more evidence.

ConclusionPosterior arthroscopic panarthrodesis offers very good results, with less comorbidity, a high rate of bone consolidation, no need for grafting, shorter hospital stay, and a lower rate of postoperative wound complications than traditional open TTC arthrodesis methods, which should be reserved for cases with significant deformities.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflicts of interests to declare which could interfere with the study results or conclusions.

FundingThe authors declare that they have received no funding for the conduct of the present research, the preparation of the article, or its publication.

Protection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that the procedures followed were in accordance with the regulations of the relevant clinical research ethics committee and with those of the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki).

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.