To retrospectively evaluate the clinical–functional outcomes, healing rates, complications, and surgical time in patients treated with superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) using long head of the biceps autograft (LHB) and Achilles allograft (AA).

Materials and methodsThis retrospective study included 24 patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus, treated with SCR. Two treatment groups were formed: one with 12 cases using AA and another with 12 cases using LHB. All patients were followed for a minimum of 2 years.

ResultsThe SSV was 73.7±25.3 vs. 86.0±8.7 (p=0.26), the Constant score was 76.8±20.1 vs. 83.7±4.6 (p=0.12), and the VAS was 1.6±2.3 vs. 1.7±0.5 (p=0.9) for the LHB and AA groups, respectively. Tendon healing was 66.7% in AA and 100% in LHB (p=0.001). Complications were 50% in AA and 0% in LHB. The average surgical time was 127.7±37.6min for AA and 84.3±14.3min for LHB (p=0.01).

ConclusionsSCR with LHB showed better results in terms of tendon healing, fewer complications, and reduced surgical time compared to the use of AA.

Evaluar retrospectivamente los resultados clínico-funcionales, las tasas de cicatrización, las complicaciones y el tiempo quirúrgico en pacientes tratados con reconstrucción capsular superior (RCS) usando autoinjerto de porción larga de bíceps (PLB) y aloinjerto de Aquiles (AA).

Materiales y métodosEstudio retrospectivo que incluyó 24 pacientes con roturas irreparables del supraespinoso e infraespinoso tratados con RCS. Se conformaron 2 grupos de tratamiento: uno con 12 casos utilizando AA y otro con 12 casos utilizando PLB. Todos los pacientes fueron seguidos durante un mínimo de 2 años.

ResultadosEl SSV fue de 73,7±25,3 vs. 86,0±8,7 (p=0,26), la escala de Constant fue de 76,8±20,1 vs. 83,7±4,6 (p=0,12) y la EVA de 1,6±2,3 vs. 1,7±0,5 (p=0,9) para los grupos PLB y AA, respectivamente. La cicatrización tendinosa fue del 66,7% en AA y del 100% en PLB (p=0,001). Las complicaciones fueron del 50% en AA y del 0% en PLB. El tiempo quirúrgico promedio fue de 127,7±37,6minutos para AA y 84,3±14,3 minutos para PLB (p=0,01).

ConclusionesLa RCS con PLB ha mostrado mejores resultados en términos de cicatrización tendinosa, menos complicaciones y un tiempo quirúrgico reducido al compararlo con la utilización de AA.

Massive, irreparable rotator cuff injuries present a significant clinical challenge, especially in young patients without glenohumeral osteoarthritis. A massive injury is considered to involve more than two tendons and is classified as irreparable in the presence of at least one of the following factors: grade 3 or 4 fatty degeneration according to the Goutallier classification, retraction of the tendon end at the level of the glenoid (Patte 3), or severe supraspinatus muscle atrophy with a positive tangent sign.1–3

These injuries have been addressed using various surgical techniques, including debridement and tenotomy of the biceps tendon, partial rotator cuff repairs, tendon transfers, and reverse shoulder arthroplasty.4–8 As of yet there is no consensus on the ideal surgical treatment.9

In 2012, Mihata published the superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) technique, which aims to restore superior shoulder stability in patients with irreparable supraspinatus injuries using a fascia lata autograft, which is fixed to the superior part of the glenoid and the supraspinatus insertion site. This technique presented encouraging clinical and functional results, along with a healing rate of 83.3%, quickly making it a therapeutic option.10 However, this procedure increases donor site morbidity, leading to the emergence of graft alternatives such as acellular dermal allograft (AIDA), Achilles tendon allograft (AA), and long head of the biceps tendon (LHB) autograft.11–14

The AA is noted for its robust, versatile, and resistant structure. Lee et al. reported good results regarding active mobility, functional scores, and pain reduction in short-term follow-up.15 However, significantly high complication rates have also been recorded, such as tendon healing failure (83.3%), reoperations, and infections.16

Also, the use of a LHB graft consists of preserving the proximal insertion of the graft, while a distal tenotomy is performed and fixed with an anchor at the level of the supraspinatus tendon insertion trace, posterior to the entrance of the biciptal groove. This graft is available for most patients, allowing for a less costly procedure, with a healing rate comparable to the original Mihata technique, and improving pain, mobility, and function scores.14,17

ObjectiveThe objective of this study was to perform a retrospective evaluation of the clinical and functional outcomes, healing rates, complications, and surgical time in two series of patients treated with LHB and AA. Since the optimal graft has not yet been determined, this study seeks to provide valuable information in comparing these alternatives for SCR.

HypothesisIt has been hypothesized that the use of LHB in SCR could generate clinical and functional outcomes comparable to AA repairs, but with a lower incidence of complications and reduced surgical time.

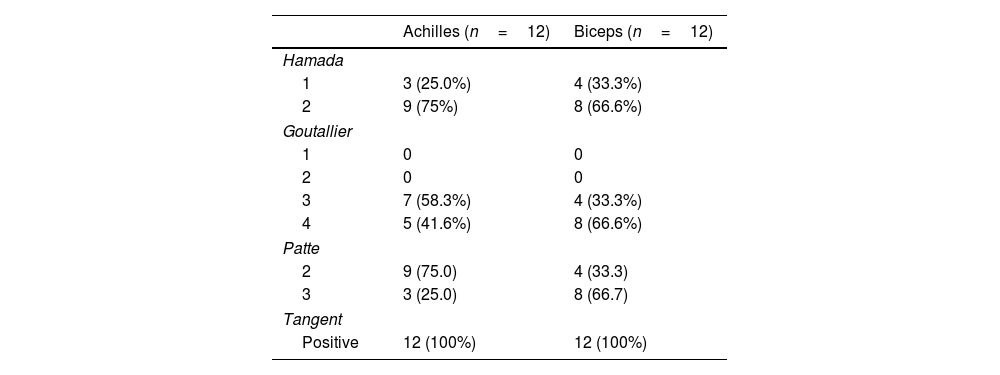

Materials and methodsA retrospective analysis of our database was performed to identify all patients with massive, irreparable supraspinatus and infraspinatus lesions consecutively treated with the SCR technique using AA and LHB. These techniques were applied in two distinct periods: initially, AA was used from January 2020 to June 2021. Subsequently, due to the surgeon's preference, the results obtained, and the available literature, it was decided to start treating these patients with LHB from July 2021 to December 2022. The AA group included all patients treated during the first period, while the LHB group comprised the first 12 patients treated in the second period. Ruptures were classified according to Collin's classification,18 and all included patients presented type D tears affecting both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons, without involvement of the subscapularis. Patients diagnosed with irreparable supraspinatus and infraspinatus tears without glenohumeral osteoarthritis (Hamada ≤2) and aged between 40 and 70 years were selected to ensure comparability between groups and avoid bias in recovery and functional outcomes. Exclusion criteria included irreparable subscapularis tendon injuries, glenohumeral osteoarthritis, a history of shoulder infection, and neurological limitations.

Twelve patients treated with RCS using AA were identified; 5 were women (41.7%) and 7 were men (58.3%), with a mean age of 64.2±7.5 years. The follow-up period for the AA group was 39.7±12 months. Matching was performed with 12 patients, including 8 men (66.7%) and 4 women (33.3%), with a mean age of 62.2±6.9 years and a follow-up period for the LHB group of 27.1±7.8 months treated with LHB, as previously described (Table 1).

Shoulder range of motion was clinically assessed by the attending surgeon before surgery and at periodic postoperative follow-ups. Clinical assessment parameters included active shoulder motion: anterior elevation in the plane of the scapula, external rotation with the shoulder adducted and the elbow flexed to 90°, and internal rotation estimated by the maximum level reached by the thumb. Additionally, a visual analogue scale (VAS) was used to determine the presence and intensity of pain, and function was assessed using the Constant–Murley scale and the subjective shoulder value (SSV).

Radiological assessmentReoperative and 2-year postoperative shoulder radiographs in anteroposterior and axial views of the scapula were reviewed. The acromiohumeral interval (AHI), determined by the distance between the apex of the humeral head and the inferior border of the acromion, was measured, and the preoperative presence of rotator cuff arthropathy was recorded according to the Hamada classification.

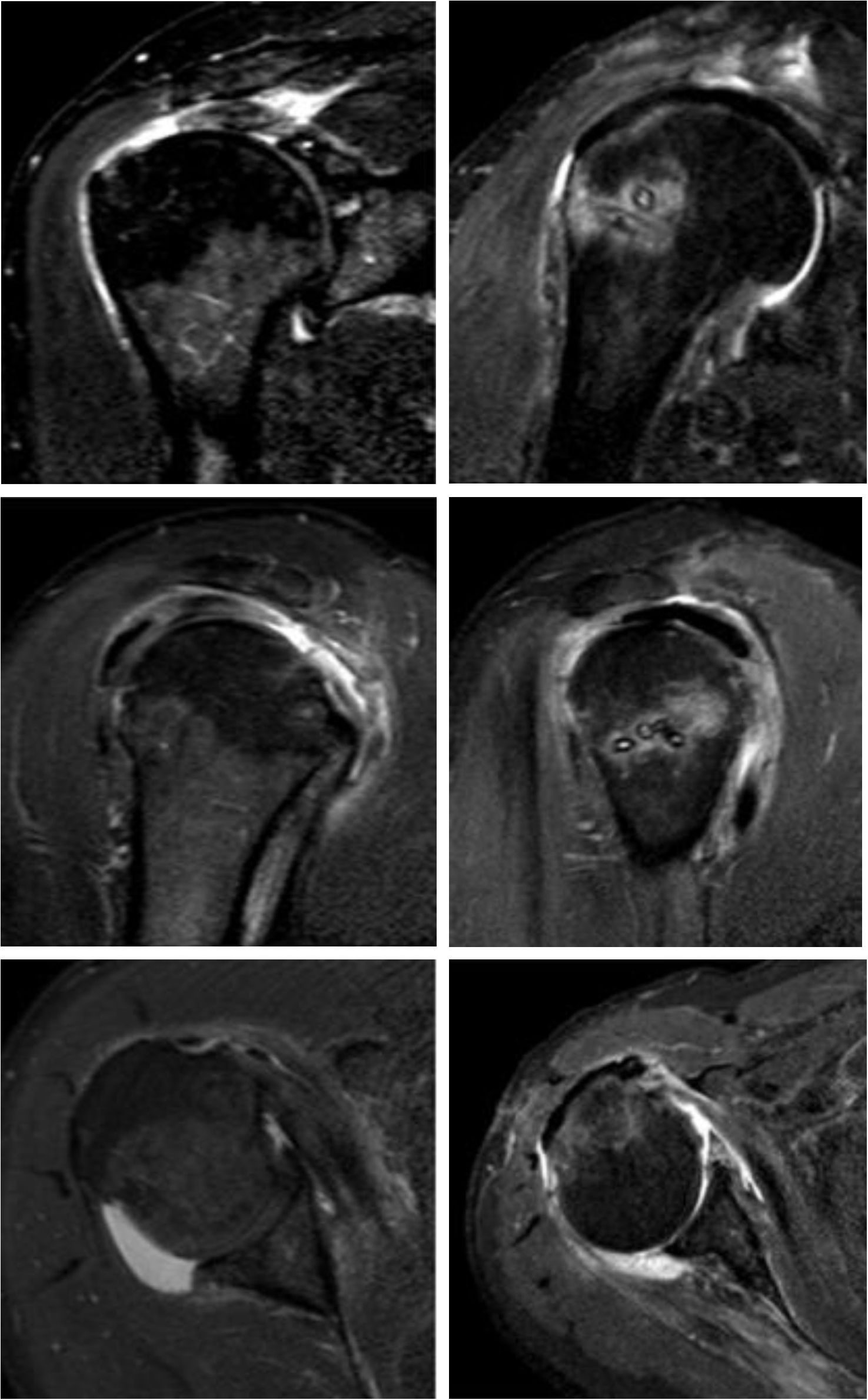

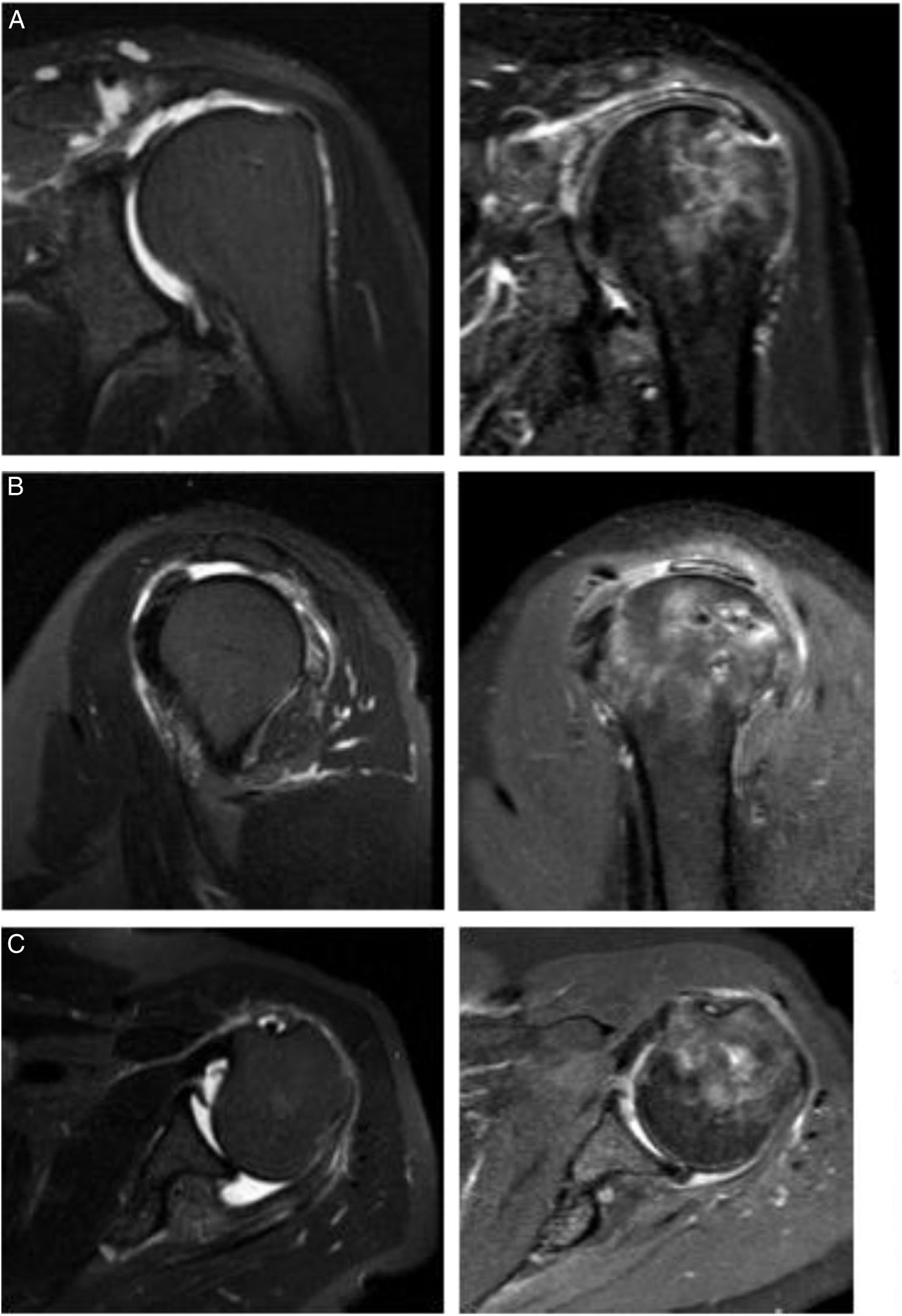

Preoperative and postoperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation was performed at 2 years. The preoperative MRI evaluation included the Goutallier classification for fatty infiltration of the muscle, the Patte classification for the degree of tendon retraction, and the tangent sign, which was measured on sagittal T1-weighted images by drawing a line tangent to the superior border of the coracoid process to the superior border of the spine, on a sagittal image at the level of the scapula.1–3 Muscles with grade 3 and 4 infiltration, grade 3 tendon retraction, or a positive tangent sign were considered irreparable, with definitive intraoperative confirmation at the surgeon's discretion. Additionally, the graft status was identified on postoperative images as continuous or discontinuous using the Sugaya classification and read by an independent imaging specialist blinded to the graft type used.19 In agreement with Bernstein et al.,20 the graft was considered continuous when it presented a homogeneous, low-intensity appearance on T1-weighted images, with no evidence of fluid interposition between the graft and its bone anchor. Healing failure was defined as any discontinuity of the tendon along its course, from its insertion into the glenoid to its insertion into the greater tuberosity, or the presence of fluid at the graft–anchor interface indicating lack of integration. Graft thickness was measured in healed tendons to assess its performance.

Intraoperative complications and reinterventions during follow-up were recorded in the medical record. In addition, the surgical time used for both the AA group and the LHB group was identified, measured in minutes.

Statistical analysisContinuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation, and qualitative variables as percentages. The two analysis groups were compared using a t-test for quantitative variables and Fisher's test for qualitative variables. A difference of <.05 was considered statistically significant. Graph Pad Prism 8.0 software was used.

Surgical techniqueAll patients underwent surgery at our centre by the same surgical team under general anaesthesia after an interscalene regional block. They were placed in the beach chair position. Exploratory arthroscopy was performed. After a wide bursectomy, the infraspinatus stump was mobilised, and partial repair was performed in all cases.

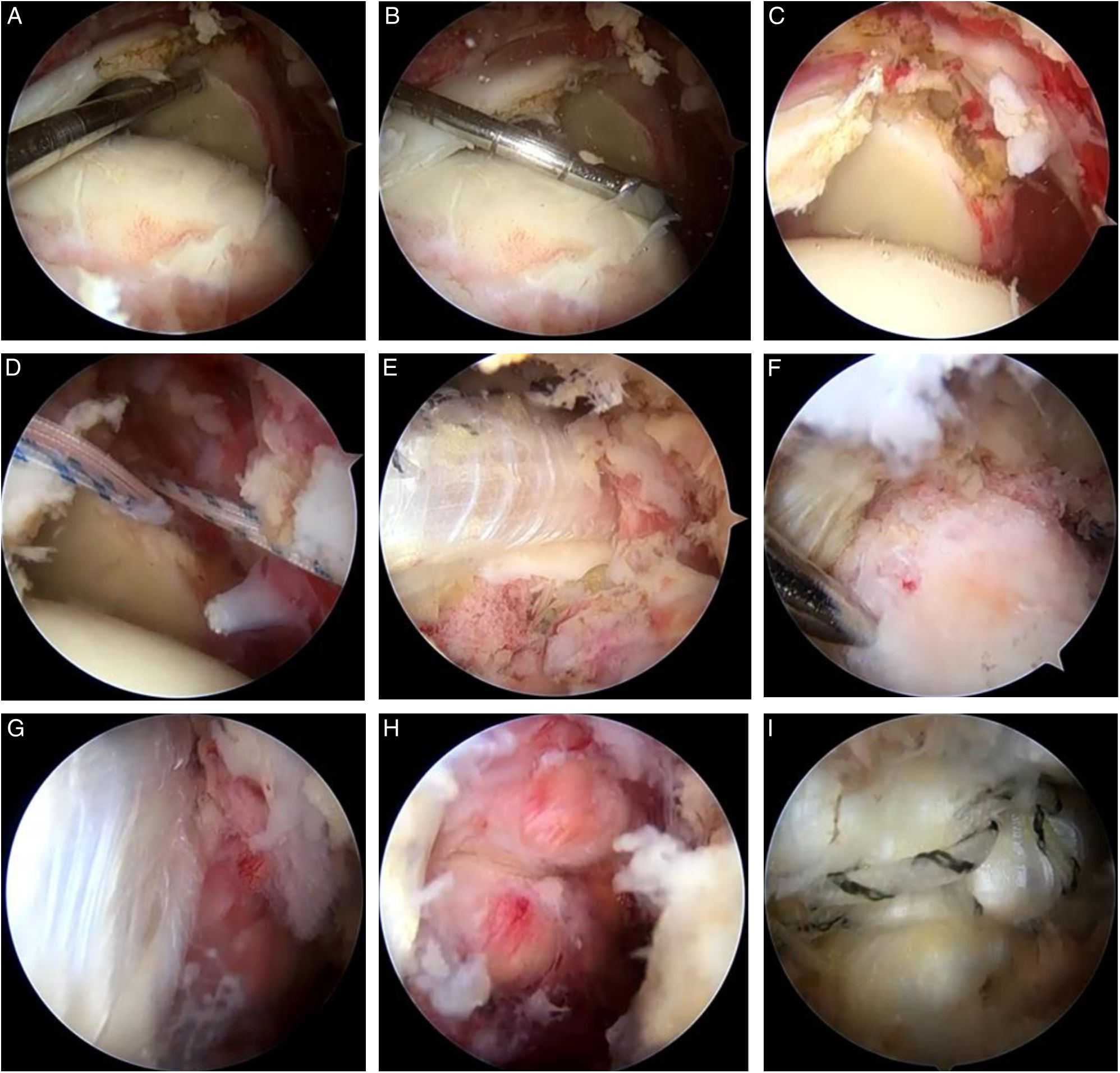

Achilles allograft technique (Fig. 1)According to the original description of the surgical technique proposed by Mease et al.,21 the superior aspect of the glenoid was branched and decorticated, resecting the labrum and the bicipital insertion, and performing a tenomic procedure. Two 3.0mm Subpunch anchors (South America Implants S.A., Canning, Buenos Aires, Argentina) were placed at 11 and 13 o’clock through the anterior portal, and a Neviaser portal at least 5mm medial to the articular margin. The mediolateral distance from the superior articular margin of the glenoid to the beginning of the supraspinatus insertion mark was then measured with a graduated palpator. One centimetre was added to this measurement on the glenoid side and 15mm on the greater tuberosity side. The graft is placed by fixing the distal part of the Achilles tendon to the glenoid and the proximal part to the humerus. This orientation was chosen because the tendon is wider proximally and narrower distally, allowing for better anatomical adaptation and more secure fixation at the bone contact points. The anteroposterior measurement was taken from the anterior margin of the infraspinatus muscle, after partial repair, to the upper border of the subscapularis muscle. Since the AA has an average maximum thickness of 8mm, it is not necessary to fold it to increase its size. Its edges were sutured with a continuous high-strength suture to obtain a uniform and resistant construct.21 The 8 suture strands from the anchors were passed along the medial edge of the graft; 4 were tied using the double pulley technique, which facilitated graft entry and correct placement. The anterior and posterior borders were secured with mattress knots using the remaining sutures. On the lateral side, fixation was performed using a double-row transosseous equivalent technique. Fixation on the lateral side was performed at 30° abduction and 20° external rotation. In all cases, a side-to-side closure was performed between the graft and the infraspinatus with two HS Fiber USP2 M5 sutures (South America Implants S.A., Canning, Buenos Aires, Argentina) (Fig. 2).

Intraoperative result with Achilles allograft (AA). Final intraoperative result of superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) with AA. (A and B) Intraoperative measurements for the construction of the Achilles allograft. (C) Preparation of the glenoid at the 11 and 13 o’clock positions for anchor placement. (D) Placement of the anchors with double sutures. (E) Sliding the allograft using the double pulley system. (F) Lateral fixation at the supraspinatus insertion site. (G) Visualisation of the fixed allograft and the remaining posterior superior cuff. (H) Partial repair of the posterior superior cuff. (I) Complete coverage of the humeral head with the AA.

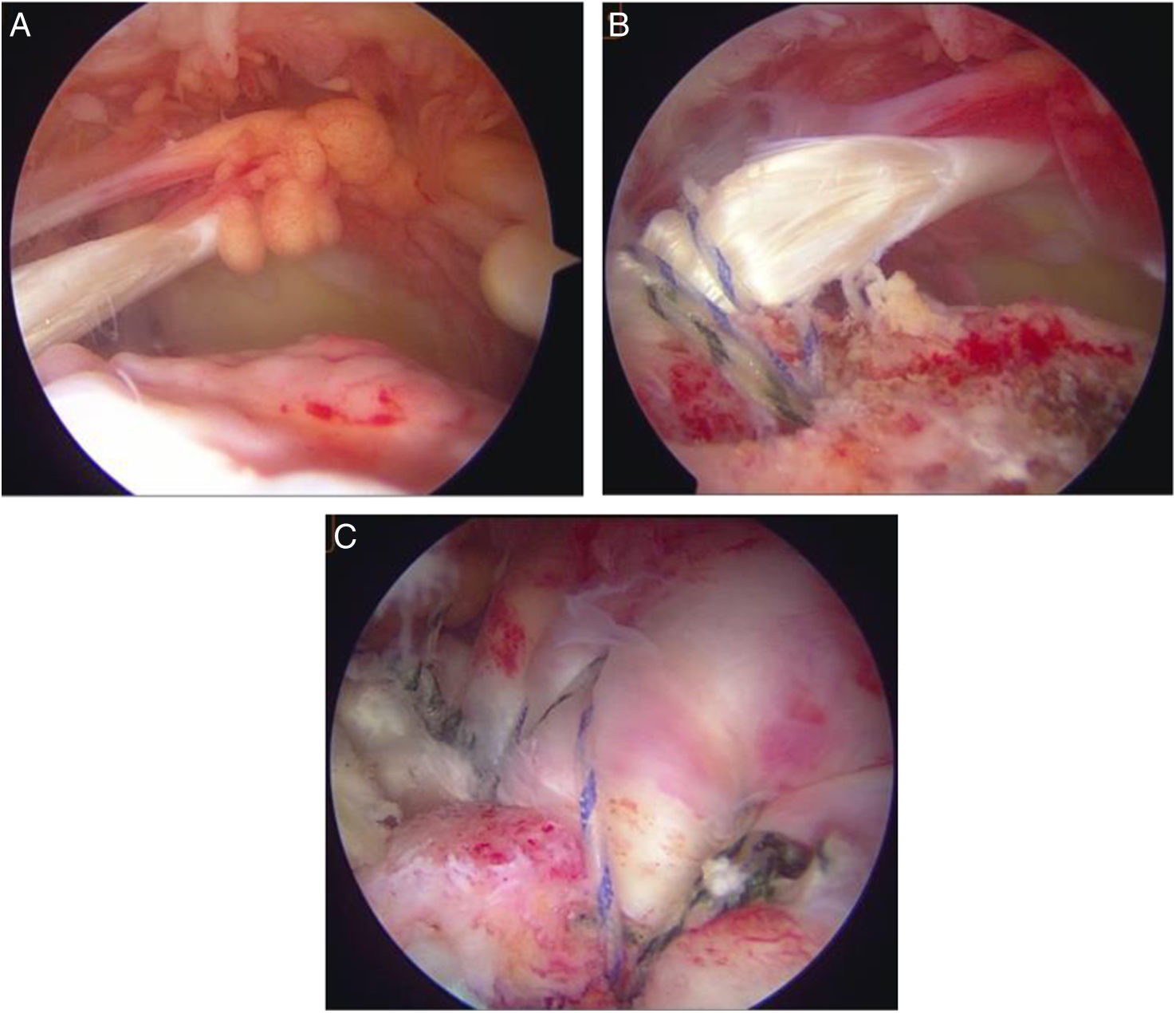

During diagnostic arthroscopy, the integrity of the biceps tendon was assessed from the posterior portal. No SLAP lesions greater than or equal to grade 2 were found, and the degenerative changes observed in the superior labrum, consistent with the patient's age, did not represent a contraindication to proceeding with SCR. The supraspinatus tendon insertion site was then crusted and decorticated. Two high-strength sutures were then introduced into the long head of the biceps, just before its entry into the bicipital groove, with a minimum of four suture passes through the tendon. The transverse ligament was then opened in the bicipital groove, followed by a tenotomy in the distal portion of the biceps, distal to the suture site. The tendon was mobilised and anchored with a 4.5mm Subtwist knotless harpoon in the center of the greater tuberosity (just behind the bicipital groove) (South America Implants S.A.®, Canning, Buenos Aires, Argentina), as described by Boutsiadis et al.14 This location optimises the tension achieved so that the tendon assumes a position appropriate to the level of the anterior rotator cuff cable. Tenodesis was not performed in any case on the remaining distal portion of the bicipital tendon. Finally, tension was verified by palpation. In all cases, a partial repair of the remaining posterior superior cuff was added (Fig. 4).

Imaging results with the long head of the biceps (LHB) autograft. The postoperative result of superior capsular reconstruction with LHB is illustrated in the following images. (A) A coronal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) section shows a Patte 3 lesion of the supraspinatus tendon and its postoperative result with LHB. (B) Sagittal MRI section shows a posterosuperior rotator cuff lesion and its resolution with LHB. (C) Posterior rotator cuff lesion on an axial MRI section and its resolution with LHB. All postoperative images were taken 2 years after LHB reconstruction.

Long head of the biceps (LHB) autograft technique. (A) Identification of a massive rotator cuff injury, clearly visualising the area devoid of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons from the lateral portal. (B) Tendinous anchorage of the LBP in the centre of the greater tuberosity. (C) Partial repair of the remaining cuff attached to the LBP.

All patients followed the same rehabilitation protocol, using a Velpeau sling for 6 weeks. Kinesiology rehabilitation began 30 days postoperatively, with passive range of motion exercises. Active range of motion without resistance was initiated at 6 weeks. Strength training activities were restricted until the third month, and sports activities or a return to strength training were permitted at the sixth month, depending on each patient's clinical progress.

ResultsThe sample demographics are detailed in Table 2.

Both the AA and LHB groups showed improvements in postoperative clinical and functional outcomes (Table 3). The LHB group showed a slight superiority over the AA group in the SSV, 86.0±8.7 vs. 73.7±25.3, and in the Constant scale, 83.7±4.6 vs. 76.8±20.1, although this did not demonstrate statistical significance (p=.26) and (p=.12), respectively. Regarding the VAS evaluation, values of 1.6±2.3 vs. 1.6±2.3 were reported. 1.7±.5 (p=.9) for the AA group and the LHB group.

Comparison of clinical–functional outcomes.

| Achilles (n=12) | Biceps (n=12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | ||

| SSV | 64.2±7.5 | 37.5±7.5 |

| Constant | 49.0±11.9 | 50.0±6.6 |

| EVA | 6.5±1.0 | 6.8±1.1 |

| EA | 108.7±39.9 | 86.7±38.4 |

| RE1 | 29.6±6.9 | 29.2±13.8 |

| RI | ||

| Gluteus | 2 (16.7%) | 9 (75.0%) |

| Lumbar vertebra # 5 | 5 (41.7%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Thoracic vertebra # 12 | 5 (41.7%) | 2 (16.7%) |

In the imaging results (Table 4), the AA group achieved greater occupation in the subacromial space, with an AHI of 9.7±2.8 vs. 7.3±.9 for the LHB group, although not statistically significant (p=.1). Likewise, the graft thickness assessed by MRI showed 6.3±1.4mm in the AA group vs. 4.6±.5mm in the LHB group (p=.1). The tendon healing rate showed a marked difference between the groups, being 66.7% for the AA group vs. 100% for the LHB group (p=.001). Regarding complications, two patients treated with AA (16.7%) required additional intervention due to infection, including allograft removal and treatment with specific antibiotics. Failure of graft healing was documented in four cases (33.4%) in the AA group. No complications were recorded in the LHB group. Comparative analysis of both techniques showed a significant reduction in surgical time in the LHB group: 84.3±14.3min vs. 127.7±37.6min for the AA group (p=.01) (Table 5).

Postoperative comparison.

| Achilles (n=12) | Biceps (n=12) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SSV | 73.7±25.3 | 86.0±8.7 | .26 |

| Constant | 76.8±20.1 | 83.7±4.6 | .12 |

| EVA | 1.6±2.3 | 1.7±.5 | .9 |

| EA | 139.2±36.0 | 151.6±35.9 | .4 |

| RE1 | 30.0±9.5 | 38.7±15.5 | .11 |

| RI | |||

| Gluteus | 3 (25.0) | 0 (0) | |

| Lumbar vertebra # 5 | 4 (33.3) | 3 (25.0) | |

| Thoracic vertebra # 12 | 4 (33.3) | 9 (75.0) | |

| Reintervention | 2 (16.7%) | 0 (0%) | .47 |

| Graft integrity | |||

| Healed | 8 (66.7%) | 12 (100.0%) | .001 |

| Broken | 4 (33.4%) | 0 (0) | |

| Complications | |||

| No | 6 (50%) | 12 (100.0%) | .01 |

| Yes | 6 (50%) | 0 (0) | |

| Tendon thickness | 6.3±1.4 | 4.6±.5 | .1 |

| IAH | 9.7±2.8 | 7.3±.9 | .1 |

| Time in surgery | 127.7±37.6 | 84.3±14.3 | .01 |

SCR using the LHB is superior in terms of tendon healing, with a lower incidence of complications and shorter surgical time compared to SCR with AA. In our study, tendon healing reached 100% in the LHB group and 66.7% in the AA group, which was statistically significant (p=.001). These excellent results are consistent with those reported by Gao et al.,22 who documented a tendon healing rate of 87.7% with the use of LHB. According to Kim et al.,23 the improvement in healing could be explained by maintaining the intact attachment of the LHB to the supraglenoid tubercle, which minimises medial failures and allows the autograft to maintain sufficient blood supply, in addition to offering better theoretical proprioception.

Understanding the advantages and disadvantages of each graft is essential when selecting the technique to be used. Furthermore, the additional costs associated with the procedure must be considered as an integral part of the decision-making process. In our study, complications were significantly lower in the LHB group, with no complications occurring during follow-up, whereas the AA group had a complication rate of 50%, with tendon failure (33.4%) and infection (16.7%) being the most common. Cases of infection required surgical lavage, allograft removal, and targeted antibiotic therapy. These findings are consistent with the results of Lädermann et al.,24 who reported a 35% complication rate associated with the use of allografts, and with the systematic review by Sommer et al.,25 who documented complication rates ranging from 5% to 70% for allografts, compared with 14–32% for autografts. In a retrospective study of 89 patients undergoing SCR using a LHB, Gao et al.,22 documented a 12.4% tendon healing failure rate and observed no other complications. Based on the findings in the literature and our results, we can affirm that the use of LHB autograft for SCR results in fewer complications compared with AA.

The primary function of the SCR is to centre the humeral head. Han et al.,26 in a biomechanical study using the long head of the biceps, demonstrated a decrease in superior translation of the humeral head and a reduction in subacromial contact pressures at 0° and 60° of glenohumeral abduction. In our results, the LHB showed a thinner thickness compared to the AA (4.6±.5 vs. 6.3±1.4; p=.1), which is expected given that the AA has an average thickness of 8mm and therefore does not require folding. However, despite this difference in thickness, no significant differences in postoperative AHI were observed during follow-up. Zhao et al.,27 point out that RCS with LHB, due to its insufficient thickness, would have a lesser spacing effect. This suggests that the “inverted trampoline” effect of RCS,28 by re-centring the humeral head, directly influences AHI values and is not solely attributed to an effect of occupying the subacromial space when positioning the graft.

The success of SCR with LHB can be attributed to both biological and mechanical factors. From a biological perspective, the LHB already has its own vascularisation, which may promote better healing and regeneration compared with an allograft.29 Mechanically, the LHB adds strength and structure to the joint capsule, contributing to the stability of the reconstruction, as reported in the study by Han et al.21 Recently, SCR with LHB without tenotomy has been described, showing favourable results. McClatchy et al.,30 postulated that keeping the LHB intact after transposition could provide a dynamic depressing and stabilising effect on the humeral head, potentially improving shoulder function by preserving the natural tension of the tendon in its new position. Furthermore, a biomechanical study in a rabbit model showed that the biceps tendon progressively remodels and heals adequately in the new transposed position, with a biomechanical strength of the superior capsule exceeding that of the native capsule.31 In our study, which covered a period prior to the publication of McClatchy's findings, we opted to perform tenotomy of the LHB. The results of the McClatchy series are promising and suggest that this technique may be a viable therapeutic alternative.

The technical simplicity of using LHB, which eliminates the need for an allograft, contributes to a reduction in surgical time, with an average of 84.3±14.3min for the LHB group, compared to 127.7±37.6min for the AA group (p=.01). This improves the technique's performance, as has also been corroborated in literature reviews highlighting the advantages of biceps autograft in terms of surgical time and risk of infection.32 Additionally, the reduced surgical time entails economic benefits and lower morbidity associated with the procedure. Furthermore, it is important to note that allograft techniques entail an additional cost, not only due to the allograft itself, but also due to the use of a greater number of bone anchors.

Both the AA and LHB groups showed improvements in functional scores (SSV and Constant) and range of motion. Although there are no direct comparative studies between AA and LHB, systematic reviews of various grafts, including acellular dermal allograft, fascia lata tendon, and LHB, have reported similar short-term clinical and functional outcomes, with improvements in range of motion and a significant reduction in pain. Demonstrating postoperative SSV scores using AIDA, FL, and LHB were 85.3 (77.5–89), 88.6 (73.7–94.3), and 82.7 (80–85.4), respectively. Likewise, improvements in VAS were observed by .8, 2.5, and 1.4, and predominantly improved anterior elevation by 159.0°, 147.0°, 163.8° respectively.33

LimitationsThis study has several limitations. First, its retrospective nature and small sample size limit the robustness of the statistical conclusions. Furthermore, the short-term follow-up does not allow for an assessment of the durability of the long-term clinical results.

Another potential selection bias stems from the way in which the techniques were applied over different time periods. Initially, the AA was used as a graft in a group of 12 patients. Subsequently, and based on the experience gained with these cases, it was decided to use the long head of the biceps tendon (LHB) in patients. This sequence in the adoption of techniques could have influenced the results due to the surgeon's evolving skills, introducing a learning bias.

Furthermore, both groups underwent additional procedures such as biceps tenotomy, debridement, and partial repairs. Although these procedures were consistent across groups, they prevent specific conclusions about the effectiveness of SCR vs. less invasive techniques, such as biceps tenotomy or isolated debridement.

It is important to mention that all surgeries and follow-up were performed by the same surgeon, which could introduce bias in the assessment of outcomes. To obtain more robust conclusions and better guide the choice of graft type in SCR, additional studies with larger numbers of patients and longer follow-up are needed. Despite these limitations, this is the only study to date directly comparing these two techniques.

ConclusionSCR using LHB demonstrated better outcomes in terms of tendon healing and fewer complications compared to the AA technique, suggesting that LHB may represent a safer treatment option. Furthermore, SCR with LHB presents additional advantages, such as reduced surgical time, supporting its usefulness as a simpler option.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki. Due to the retrospective nature of the study and the fact that all patients completed their treatment, informed consent was not obtained. Waiver of informed consent was requested for this study. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the British Hospital of Buenos Aires.

All measures were taken to ensure data confidentiality. Furthermore, the Personal Data Protection Act was respected, ensuring that the anonymity of the participants was maintained at all stages of the study.

FundingNone of the authors received funding or benefits from any commercial entity that may have an interest in the results presented in this article. All procedures and analyses were performed independently and transparently, ensuring the objectivity and integrity of the study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to this study.