Ankle fractures are increasingly common in frail patients, with hospitalisation being the principal cost driver, particularly for the elderly who often need referral to nursing facilities. This study aims to identify factors affecting resource utilisation per admission (hospital and nursing) in the fixation of low-energy ankle fractures.

Materials and methodsThis retrospective cohort study examined patients undergoing fixation for low-energy ankle fractures. The primary outcome was the length of hospitalisation. Secondary outcomes included delays in fixation and the need for referral to a nursing institution. Multiple linear and logistic regression models were used to determine predictors related to patient demographics, injury characteristics, and treatment.

ResultsWe analysed 651 patients with a median age of 58years. The median hospitalisation duration was 9days, primarily before surgery. Extended hospitalisation was associated with antithrombotic treatment (b=4.08), fracture-dislocation (2.26), skin compromise (7.56), complications (9.90), and discharge to a nursing centre (5.56). Referral to a nursing facility occurred in 17.2%, associated with older age (OR=1.10) and an ASA score≥III (6.96).

ConclusionsProlonged hospitalisation was mainly due to surgical delays and was related to fracture-dislocations, skin compromise, and complications. Older and comorbid patients were more likely to need nursing facilities, and delays in these facilities’ availability contributed to extended hospital stays.

Las fracturas de tobillo presentan una incidencia creciente en pacientes frágiles. La hospitalización representa el principal coste en su manejo, siendo mayor en ancianos, quienes habitualmente necesitan derivación a centros para convalecencia. Nuestro objetivo es determinar qué factores influyen en el consumo de recursos por ingreso (hospitalario y sociosanitario) en la osteosíntesis de las fracturas de baja energía de tobillo.

Material y métodoEstudio de cohortes retrospectivo sobre pacientes sometidos a osteosíntesis por fracturas de baja energía de tobillo. El resultado primario fue la duración de la hospitalización. Secundariamente, analizamos el retraso en la osteosíntesis y la necesidad de derivación a una institución sociosanitaria. Empleamos modelos de regresión múltiple lineal y logística para identificar los factores predictores relacionados con los pacientes, lesiones y tratamientos.

ResultadosAnalizamos 651 pacientes con una mediana de edad de 58años. La hospitalización mediana fue de 9días, predominando antes de la cirugía. En el análisis multivariable, una hospitalización más prolongada se asoció con: tratamiento antitrombótico (b=4,08), fractura-luxación (2,26), sufrimiento cutáneo (7,56), complicaciones (9,90) y alta a centro sociosanitario (5,56). El 17,2% de pacientes necesitó derivación a un centro sociosanitario, lo que se asoció con mayor edad (OR=1,10) y puntaje ASA≥III (6,96) en la regresión multivariable.

ConclusionesLa hospitalización se prolongó, en mayor medida, por la demora de la cirugía y en relación con fracturas-luxaciones, sufrimiento cutáneo y complicaciones. Los pacientes comórbidos y de edad avanzada necesitaron centros sociosanitarios más frecuentemente. La demora en la disponibilidad de esos centros retrasó el alta hospitalaria.

Ankle fractures are very frequent injuries, accounting for 10% of all fractures and the second most common reason for hospitalisation and surgery due to fractures after hip fractures. The incidence of these injuries has been on the rise in recent decades, most notably in the elderly population.1–4 Surgical stabilisation of ankle fractures in frail patients contributes positively to their survival. Nevertheless, it does so at the expense of an increased risk of complications, which is regarded as acceptable.5,6 Concomitantly, resource utilisation also increases in older patients, as well as with more comorbidities.7,8

Hospitalisation constitutes the main cost involved in treating ankle fractures, with a clear predominance of the length of preoperative hospitalisation, which is determined by both medical and organisational factors.9,10 Many individuals, typically those who are more impaired at baseline, will ask to be admitted to a healthcare facility following hospitalisation, placing additional stress on healthcare economics.11–13 The main objective of this work is to ascertain which factors come to bear on the length of hospitalisation for osteosynthesis of low-energy ankle fractures. Secondarily, we look into which factors are associated with a delay in receiving surgery and the need to be referred to a nursing home after hospitalisation. We hypothesise that a decline in patients’ baseline characteristics, along with the presence of more severe injuries that require more complex treatment, are associated with greater healthcare resource use.

Material and methodThe present retrospective cohort study was approved by our Clinical Research Ethics Committee (reference number PR(ATR)397/2017) and the wording conformed to the STROBE statement. All of the subjects underwent surgery at a single public, tertiary-level university hospital between November 2009 and April 2019. All of the cases were taken from a database that has been used in an earlier publication, which included skeletally mature patients (aged≥15years) who underwent osteosynthesis for low-energy malleolar fractures (AO/OTA segment 44).14 As per the hospital's protocol, all were admitted pending surgical treatment. For the purposes of this analysis, individuals who had previously been in nursing homes or other social and health care institutions were excluded.

The dependent variable (outcome) “hospitalisation” was defined as the period from admission to discharge and was expressed in days. The variable “delay in osteosynthesis” was stated as the interval from admission to fixation of the fracture, corresponding to pre-operative “hospitalisation” and was articulated in days. Discharge to a nursing facility was defined as referral to a public or private residential convalescent facility in participants who had previously not been in a nursing home, and who had previously been excluded.

We compiled independent variables related to the participants’ baseline characteristics, their injuries, and treatments provided (Table 1). To improve analytical performance, we chose to test a limited number of predictors the validity of which was substantiated by the bibliography available.

Predictor definition and sample description.

| Predictors | Resultsa |

|---|---|

| Age: Age (in years) at the time of admission for treatment for fracture | 58 (28) |

| ASA: American Society of Anaesthesiologists Physical Status Classification System | |

| I: Healthy patient | 208 (32.0) |

| II: Mild systemic disease | 319 (49.0) |

| III/IV: Severe/constant life-threatening systemic disease | 124 (19.0) |

| Antithrombotic treatment: on-going treatment with clopidogrel, coumarins, or new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) | 38 (5.8) |

| Open fracture: injury related to any fracture site | 25 (3.8) |

| Fracture-dislocation: significant incongruence in the ankle joint at the time of fracture that requires reduction manoeuvres during initial management | 149 (22.9) |

| Preoperative skin injury: severe bruising or abrasion, blisters, or necrosis | 144 (22.1) |

| Delay in osteosynthesis: days elapsed between admission and osteosynthesis | 5 (6) |

| Fracture fixation | |

| Unimalleolar: synthesis of the fibula or tibia | 307 (47.2) |

| Bimalleolar: both the fibula and the tibia are synthetised | 344 (52.8) |

| Complications during admission: local postoperative or medical complications that required specific medical or surgical management | 95 (14.6) |

| Discharge to a community convalescent centre: referral to a public or private residential centre at the time of discharge | 112 (17.2) |

The X-rays and medical records of each case were assessed only once by the same researcher. Data were collected on forms and were then entered into a database in Microsoft Excel format. Validation rules were applied at entry and the database underwent a two-fold cleaning process. Cases with missing data for any of the variables studied were excluded in the final analysis. In order to verify the randomness of the data loss, test runs were performed on the variable “age” of those subjects who were eliminated.

To maximise statistical power, we included all the individuals from our database who were eligible. Statistical analyses were performed using the Stata 14.2 software (StataCorp, USA). We first conducted a descriptive analysis, representing categorical variables as counts and percentages, and continuous variables as medians and interquartile ranges, and according to their distribution. To determine whether there were differences between continuous variables, we compared their means using Student's t-test. We calculated linear regression coefficients (b), their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) and associated p-values using multiple linear regression to quantify the association between predictors and both continuous outcomes (hospitalisation and osteosynthesis delay). To gauge the association between predictors and the dichotomous outcome (discharge to a convalescent institution), odds ratios (OR), their 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and p-values were calculated using multivariable logistic regression. A univariate analysis was initially conducted. Next, a parsimonious model was generated containing all statistically significant independent variables in that model. A backward stepwise fitting technique was applied to fit the multivariate model. At each step, the variable with the highest p-value was eliminated until all p-values were ≤0.20. The “delay in osteosynthesis” variable was not tested for any of the continuous outcomes because it was strictly collinear with them. Complications were recorded indistinctively of whether they occurred during the pre- or post-surgery period, and the need for discharge to a convalescent centre was only examined once the surgery had been completed. Therefore, both variables lacked the necessary precedence to evoke causality on osteosynthesis delay, and were therefore excluded from this analysis. We ruled out other interactions and confounding factors. Any value of p<0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

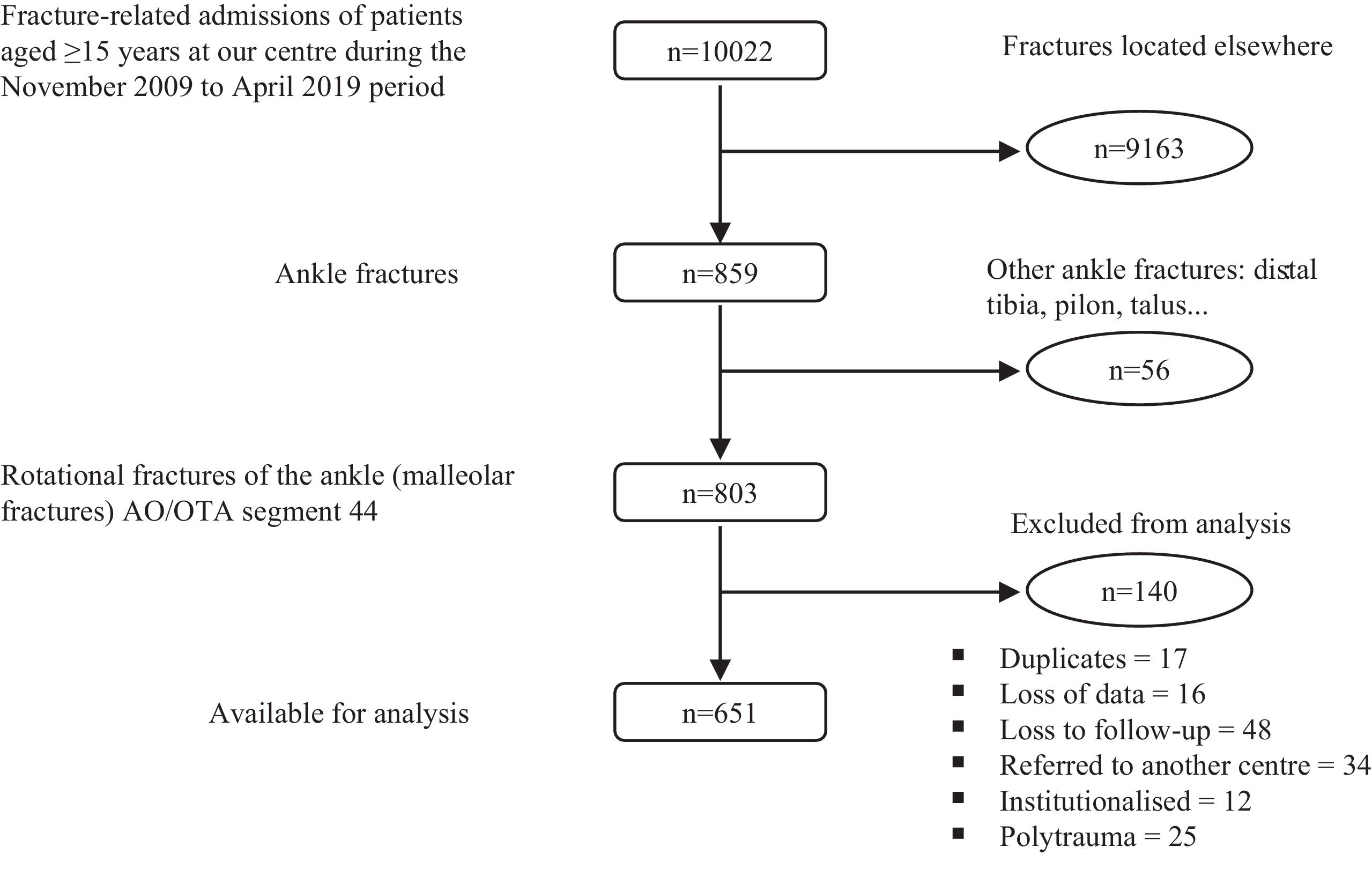

ResultsWe identified 803 potential participants, of whom 17 were discarded due to duplicate records; 16 due to loss of data, and 48 because they were lost to follow-up. The ages of the missing cases were completely random (p=.71); thus, we concluded that the loss of these data did not represent a source of bias. Thirty-four patients were referred to other health centres, predominantly in connection with traffic and sports accidents, and 25 polytraumatic cases were excluded, which might have skewed the sample only slightly, as these situations tend to occur in younger individuals. An additional 12 subjects who had been in residential care prior to their injury were likewise omitted. Therefore, the sample ultimately comprised 651 participants with a median age of 58years (IQR=28) for analysis (Fig. 1). Table 1 depicts the independent variables.

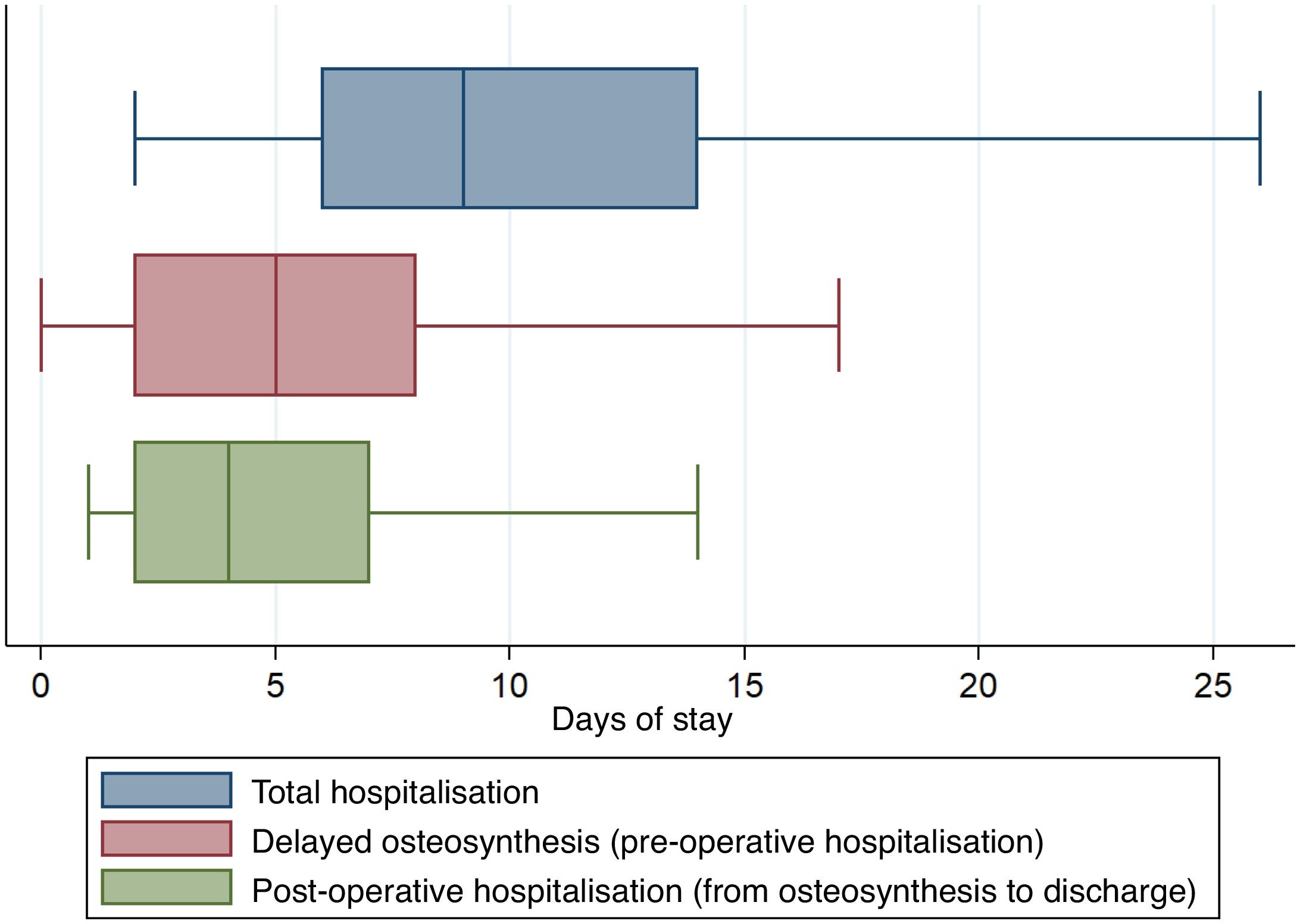

Median hospitalisation was 9days (IQR=5) and osteosynthesis delay, 5days (RIQ=6). Preoperative hospitalisation (osteosynthesis delay) outweighed postoperative hospitalisation (mean 6.4 vs. 5.6 days; p=0.03) (Fig. 2). One hundred and twelve patients (17.2%) were transported to convalescent facilities upon hospital discharge.

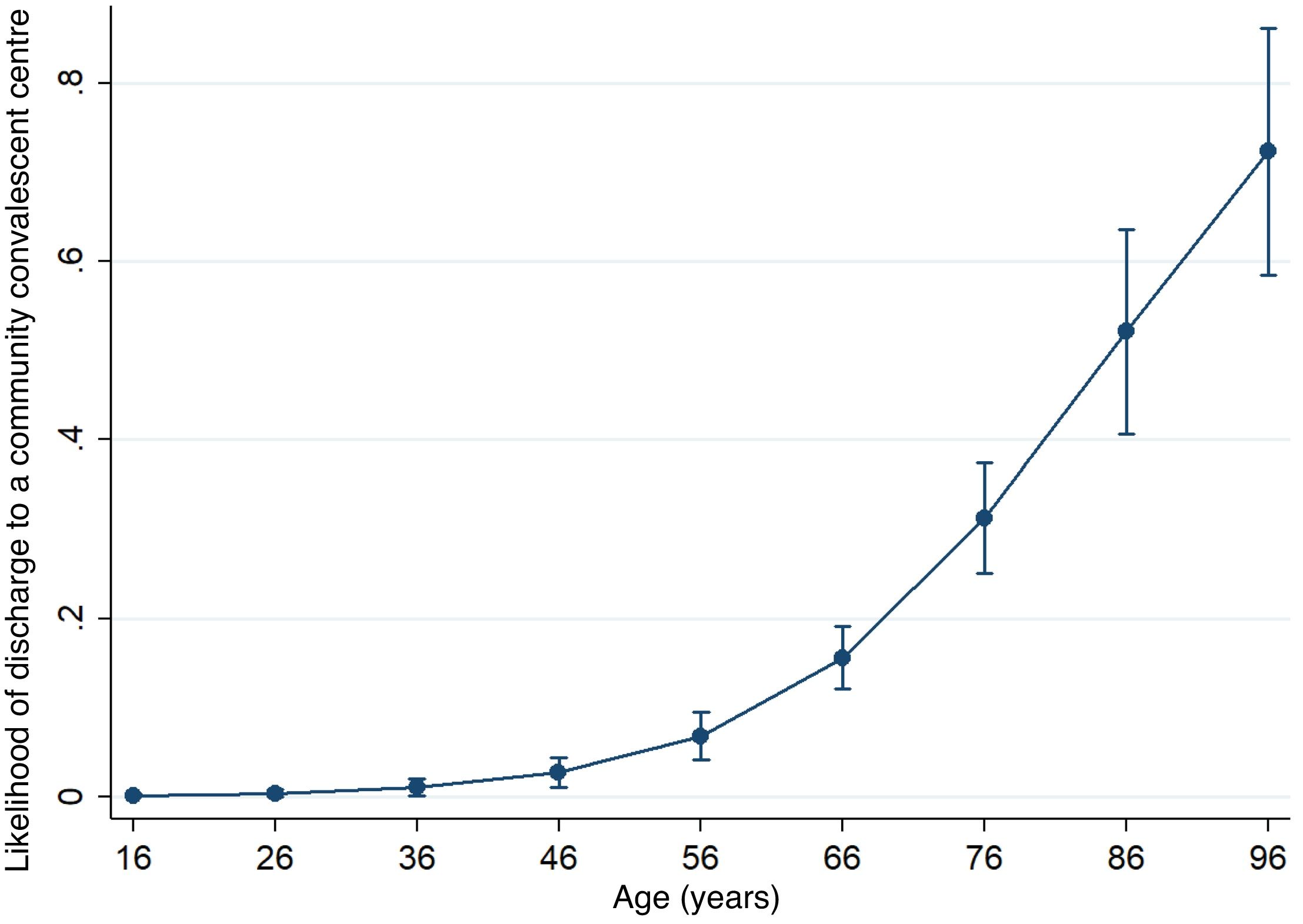

The multivariate analysis established that hospitalisation was significantly longer in those individuals who were receiving antithrombotic treatment (b=4.08; 95% CI: 1.19–6.97; p<.01); those who presented with a fracture-dislocation (b=2.26; 95% CI: 0.75–3.77; p<.01) or preoperative skin affliction (b=7.56; 95% CI: 5.96–9.16; p<.01), those who suffered any medical or local complication during admission (b=9.90; 95% CI: 8.04–11.77; p<0.01), as well as those who required transfer to a convalescent centre at discharge (b=5.56; 95% CI: 4.37–6.76; p<0.01). Similarly, osteosynthesis was delayed in those subjects under antithrombotic treatment (b=3.31; 95% CI: 1.48–5.15; p<0.01), with fracture-dislocations (b=1.89; 95% CI: 0.83–2.96; p<.01), and those with soft tissue involvement prior to surgery (b=6.57; 95% CI: 5.49–7.64; p<.01). As for the likelihood of being referred to a conval scent centre upon discharge, the multivariate analysis found that only age (OR=1.10 per year; 95% CI 10.8–1.13; p<.01); 95% CI) and an ASA score≥III as compared to an ASA score=I (OR=6.96; 95% CI: 2.33–20.75; p<.01) constituted significant predators. Fig. 2 displays a plot of predicted marginal effects for the probability of referral to a healthcare centre at discharge on the basis of the individual's age, while Table 2 depicts the outcome of the multivariate analyses in detail.

Results of the multivariate analysis (linear and multiple logistic regressions).

| Predictorsa | Resultsb | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalisation (days)c | Delay in osteosynthesis (days)c | Discharge to a convalescent centred | |

| Age (years) | E | E | 1.10 (1.08–1.13); <0.01 |

| ASA | |||

| II | 1.13 (−0.28–2.54); 0.12 | E | 2.79 (0.99–7.85); 0.05 |

| ≥III | 1.73 (−0.34–3.80); 0.10 | E | 6.96 (2.33–20.75); <0.01 |

| Antithrombotic treatment | 4.08 (1.19–6.97); <0.01 | 3.31 (1.48–5.15); <0.01 | 0.47 (2.33–20.75); 0.10 |

| Open fracture | E | E | NT |

| Fracture-dislocation | 2.26 (0.75–3.77); <0.01 | 1.89 (0.83–2.96); <0.01 | NT |

| Preoperative skin injury | 7.56 (5.96–9.16); <0.01 | 6.57 (5.49–7.64); <0.01 | 1.49 (0.82–2.73); 0.19 |

| Delay in osteosynthesis (days) | NT | NT | 1.03 (0.81–2.73); 0.19 |

| Bimalleolar fixation of the fracture | 1.28 (−0.23–2.59); 0.05 | 0.66 (−0.24–1.56); 0.15 | NT |

| Complications during hospitalisation | 9.90 (8.04–11.77); <0.01 | NT | NT |

| Discharge to a convalescent centre | 5.56 (4.37–6.76); <0.01 | NT | NT |

Categorical predictors always weighted according to the reference category: absence of the characteristic for dichotomous variables and the basic category for ordinal variables. (ASA I and unimalleolar fixation, respectively). In the case of continuous predictors, it reflects the change for each unit of increase of the characteristic.

“NT” for cells containing predictors not evaluated for that variable as a result of its co-linearity, lack of causality, or absence of statistical significance in the univariate analysis. “E” for predictors that were excluded due to backward stepwise fitting. Boldface type has been used for the cells that contain non-significant results.

The univariate analysis showed that the strongest predictors of a more prolonged hospital stay were skin discomfort and the presence of complications during hospitalisation (Table 3). It is worth noting that the findings of this analysis require some caution and we do not highlight the results of this analysis for that reason.

Results of the univariate analysis (simple linear and logistic regressions).

| Predictorsa | Resultsb | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalisation (days)c | Delay in osteosynthesis (days)c | Discharge to a convalescent centred | |

| Age (years) | 0.15 (0.10–0.19); <0.01 | 0.05 (0.02–0.77); <0.01 | 1.12 (1.09–1.14); <0.01 |

| ASA | |||

| II | 3.46 (1.70–5.23); <0.01 | 1.25 (0.14–2.36); <0.01 | 8.09 (3.18–20.60); <0.01 |

| ≥III | 7.24 (5.00–9.49); <0.01 | 3.18 (1.77–4.59); <0.01 | 31.32 (12.04–81.44); <0.01 |

| Antithrombotic treatment | 8.08 (4.73–11.43); <0.01 | 4.39 (2.31–6.48); <0.01 | 3.47 (1.75–6.89); <0.01 |

| Open fracture | 8.23 (4.12–12.33); <0.01 | 4.69 (2.14–7.25); <0.01 | 1.55 (0.60–3.97); 0.36 |

| Fracture-dislocation | 6.02 (4.17–7.86); <0.01 | 5.58 (5.03–6.13); <0.01 | 1.37 (0.86–2.17); 0.19 |

| Preoperative skin injury | 12.35 (10.68–14.02); <0.01 | 7.30 (6.25–8.35); <0.01 | 2.44 (1.57–3.80); <0.01 |

| Delay in osteosynthesis (days) | NT | NT | 1.06 (1.03–1.09); <0.01 |

| Bimalleolar fixation of the fracture | 5.57 (4.03–7.11); <0.01 | 5.14 (4.43–5.85); <0.01 | 2.48 (1.59–3.84); <0.01 |

| Complications during hospitalisation | 13.98 (11.99–15.97); <0.01 | NT | 0.89 (0.49–1.61); 0.69 |

| Discharge to a convalescent centre | 7.70 (5.67–9.74); <0.01 | NT | NT |

Categorical predictors always weighted according to the reference category: absence of the characteristic for dichotomous variables and the basic category for ordinal variables. (ASA I and unimalleolar fixation, respectively). In the case of continuous predictors, it reflects the change for each unit of increase of the characteristic.

“NT” for cells containing predictors not evaluated for that variable as a result of its co-linearity, lack of causality, or absence of statistical significance in the univariate analysis. “E” for predictors that were excluded due to backward stepwise fitting. Boldface type has been used for the cells that contain non-significant results.

In our 651-patient sample who underwent surgery for low-energy ankle fractures, elderly patients with various comorbidities predominated. The median hospital stay was 9days, with extended hospitalisations taking place during the preoperative as opposed to the postoperative period. The complexity of the injury itself (such as fracture-dislocations or those involving the skin prior to fixation), the emergence of complications, as well as the need for referral to convalescent centres were factors that prolonged hospital stay. Following surgery, 17.2% of the study population needed some kind of socio-healthcare resource, a trend that was further aggravated by being older and having a greater burden due to co-morbidities.

The median length of hospital stay in our sample was 9days, while the published literature reports central tendency measures of hospitalisation time ranging from 1.9 to 10.8 days.7,15–22 The contribution of preoperative hospitalisation (osteosynthesis delay) to the total computation of hospitalisation exceeded postoperative hospitalisation, with a median of five versus four days. This predominance is consistent with other publications, which have documented surgical delays that vary between 1.9 to 7 days.17,21,23–25 That being said, it should be noted that there is tremendous heterogeneity in the treatment protocols and the organisation of the healthcare system in question of the published samples, thereby hindering comparisons.7,15–22,26 Hospitalisation is the number one driver of healthcare resource utilisation within the context of ankle fractures.9,10,20–22,26 Of course, costs increase linearly with the length of hospital stay. Older require not more frequent hospital stays, but also longer ones, irrespective of whether conservative or surgical treatment is the modality used.8,22,27 These individuals typically have comorbidities, which are commonly characterised by means of perioperative risk and assessment scales, such as the ASA scale. These tools have proven to correlate well with prolonged hospitalisation.7,8,13,15,16,19,20,26 Unfortunately, our multivariate analysis failed to replicate the correlation between age, comorbidity, and length of hospital stay. We attribute this to the fact that our study population exhibited poorer patient profiles, with a median age of 58 years and significant comorbidities (ASA≥II) in 68% of cases, which is most likely due to the eligibility criteria applied.

Any number of reasons can lead to delayed surgical treatment of an ankle fracture. Medical factors include increased soft tissue injury, which is generally more severe in individuals who are sharing off in a worse baseline situation.24,27–29 Surgery that is performed on an ankle fracture where the skin coverage has been compromised increases the risk of postoperative complications. Therefore, the state of the skin and the degree of oedema are decisive when selecting when to proceed with surgery, which is often delayed to allow swelling to subside and damaged areas, such as those with blistering, to heal. Likewise, an injury that debuts as a fracture-dislocation is also associated with longer operative delays and hospitalisation. These injuries are especially unstable and often accompanied by more severely affected wound coverage.14,24 Hospitalisation tends to be prolonged relative to the time spent on soft tissue recovery and complication management, which are more commonly encountered in these kinds of cases.15,23,24,31 Some authors allege that early surgical stabilisation prevents oedema and skin breakdown, which may also potentially shorten the length of hospital stay.18,30 Antithrombotic treatment was also associated with prolonged surgical delay and hospitalisation. Despite the existence of a variety of strategies to titrate or reverse the anticoagulant effect of these drugs, the surgical procedure is simply delayed in most cases, seeking to lessen the risk of bleeding and issues with healing.32 Nevertheless, we must bear in mind that anticoagulated individuals who suffer fractures are fragile by definition, and that they tend not to benefit from pushing back the surgery.33 In any event, the main underlying factors for delayed procedures reported in the literature concern logistics (organisational problems and the availability of the operating theatre).27,30

Inasmuch as the main source of healthcare costs is hospitalisation and that preoperative hospitalisation lasts longer, some authors have proposed that in such fractures, preoperative management should be carried out on an outpatient basis (without admission prior to surgery), a modality with which we have no experience at our centre. The protocols and inclusion criteria proposed are highly disparate.8,17–19,34 Provided that resources are correctly allocated and adapted, outpatient care of ankle fractures can lead to greater patient satisfaction and shrink the healthcare by an order that ranges from 35.5% to 75%.8,19,34 Nevertheless, despite the economic advantages, there are a number of caveats to implementing these protocols. Managing those individuals who have a poorer functional status at home is extremely challenging when their ankle is immobilised and they must stay off it.17,18 Furthermore, a number of situations can prejudice treatment outcomes, such as the presence of persistent oedema or injured skin, not having an operating theatre available to schedule the procedure, secondary displacement of the fracture while immobilised, and pain control with oral analgesia.8,17,18 Moreover, outpatient preoperative care exacerbates the delay in the osteosynthesis procedure, which some authors have linked to an increased risk of complications and impaired ankle function.23,24

Despite being a major source of healthcare resource utilisation, which in our sample comprised 17.2% of the cases, the need to remain in a community healthcare institution to convalesce post-osteosynthesis of an ankle fracture is a situation that has been the object of scant research in the literature. Age is the primary risk factor for needing to be referred to a convalescent facility following a fracture of the lower extremity, with an exponential trend (Fig. 3). Older age is often accompanied by a declining comorbidity profile, and poorer scores on comorbidity and perioperative risk scales have also been associated with increased care needs during convalescence.11–13 The duration of hospitalisation has been less consistently reported as a predictor of the need for convalescent care. In the present work, we have found that the necessity for referral to such centres extends the length of hospitalisation, and not vice versa. It is logical that patients with a more torpid postoperative course or who have a worse baseline profile require longer hospital stays and more frequent need to be admitted to community convalescent centres.12 It is worth pointing out that convalescence in these centres has, in turn, been linked to an increase in morbidity and mortality during the post-operative period of fragility fracture; the patient and his or her relatives should be warned about this.35 Given that beds may not be readily available at the destination institution, this can prolong hospital admission for purely organisational reasons; diligence in these arrangements is key.

We acknowledge the limitations of this study; of particular note is its retrospective nature and single-centre recruitment. The specific definition we have applied to our eligibility criteria has led to a skewed study population in terms of baseline characteristics, with many of them being elderly and having comorbidities. Notwithstanding, we do feel that the substantial sample size, the rigorous statistical analyses, and the probe into the results of special relevance to the reality of managing our healthcare system enhance the value of the message of this work.

In conclusion, hospitalisation for the surgical treatment of low-energy ankle fractures was prolonged, primarily at the expense of delayed surgery, which was longer in cases with fracture-dislocations and with greater soft-tissue injury. Complications also entailed a longer hospital stay. Older patients and those with more comorbidities required convalescence in community nursing homes more often. Delays in the availability of this resource postponed hospital discharge, which could be attributed to organisational reasons. The steady increase in the incidence of these ubiquitous injuries justifies the need for future research with the aim of optimising the management of the resources required for their treatment.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iii.

Contribution of the authorsAll authors contributed to the conceptualisation and design of the study. Materials preparation and data collection and analysis were carried out by JVAP, MMRV, OPA, MAC, and SCA. The first draft of the manuscript was written by JVAP and MMRV. All authors contributed to the creation of subsequent drafts. All authors read and approved the final version.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by our Clinical Research Ethics Review Board (CRERB) with reference number PR(ATR)397/2017).

Consent to participate and publishThis is a retrospective study. It was conducted without risk to the patients and all data collected are devoid of any link to the identity of the participants. As a result, the Ethics Committee approved a full waiver of any informed consent form.

FundingThis study received no external sources of funding whatsoever.

Conflict of interestThe authors have conflicts of interest to declare with Smith & Nephew, Zimmer-Biomet, Link-Orthopaedics, Stryker, Arthrex, and MBA Surgical Empowerment.

Data availabilityData supporting the findings of this paper are available from the corresponding author, JVAP, upon reasonable request.