Non-surgical management of intracapsular hip fractures is rare and reserved for fragile patients with comorbidities that contraindicate surgery. The aim of the study is to determine the mortality rate in intracapsular hip fractures managed non-surgically.

Material and methodsRetrospective series of patients who received non-surgical management between January 2004 and December 2023 included, minimum follow-up 1 year. Periprosthetics or secondary-to-tumor fractures, polytraumatized and surgically treated intracapsular hip fractures were excluded. Mortality was recorded during admission, at 30 days, 6 months and one year.

ResultsNon-surgical management was indicated in 54 patients (frequency 7.56%), the most common reason was low functionality (Barthel Index <20 points) associated with non-ambulation and/or neurological disease/dementia. Two patients were excluded due to loss of follow-up. During admission, 3 patients died (5.8%), at 30 days 8 patients (15.4%), at 6 months 23 patients had died (44.2%) and in the first year 30 patients (57. 7%). It was observed that the deceased patients were older (mean age 89.7 years versus 83 years); and association between mortality at one year and Barthel Index (p=0.019) and mobility 30 days after the fracture (p=0.006).

ConclusionWe present a high one-year mortality (57.7%), higher than published for surgery, so we believe that in fragile patients we must either improve multidisciplinary outpatient follow-up or consider other palliative care, without reaching harsh therapeutic treatment.

El manejo no quirúrgico de las fracturas intracapsulares de cadera es infrecuente, reservándose para pacientes frágiles con comorbilidades que contraindican la cirugía. El objetivo del estudio es determinar la tasa de mortalidad en las fracturas intracapsulares de cadera manejadas de forma no quirúrgica.

Material y métodosSerie retrospectiva de pacientes que recibieron manejo no quirúrgico entre enero de 2004 y diciembre de 2023, ambos incluidos, con un seguimiento mínimo de un año. Quedaron excluidas las fracturas tratadas quirúrgicamente, periprotésicas, por tumores o los pacientes politraumatizados. Se registró la mortalidad durante el ingreso, a los 30 días, a los 6 meses y al año.

ResultadosEn 54 pacientes se indicó un manejo no quirúrgico (frecuencia 7,56%), el motivo más frecuente fue una baja funcionalidad (índice Barthel<20puntos) asociada a la no deambulación y/o enfermedad neurológica/demencia. Se excluyeron 2 pacientes por pérdida de seguimiento. Durante el ingreso fallecieron 3 pacientes (5,8%), a los 30 días 8 pacientes (15,4%), a los 6 meses 23 pacientes (44,2%) y en el primer año habían fallecido 30 pacientes (57,7%). Se observó que los sujetos fallecidos eran mayores (edad media 89,7 años frente a 83 años) y la asociación entre mortalidad al año e índice de Barthel obtuvo una p=0,019, y la movilidad a los 30 días de la fractura p=0,006.

ConclusiónPresentamos una elevada mortalidad al año (57,7%), superior a la publicada para el tratamiento quirúrgico, por lo que creemos que en pacientes frágiles debemos bien mejorar el seguimiento ambulatorio multidisciplinar, bien plantearnos otros cuidados paliativos, sin llegar al encarnizamiento terapéutico.

Hip fractures represent a major healthcare problem. They are common in elderly patients with multiple pathologies due to bone fragility secondary to osteoporosis.1,2 Thirty-day mortality ranges from 7.4% to 20%,3–5 rises between 10% and 63% in the first year,2–8 and specifically in the Spanish population, ranges from 13% to 30%,9 in patients over 80 years of age having a 3.6 times greater risk of dying during this first year.9 As a result, the postoperative period is critical to clinical outcome.1,2,8

The treatment of choice for hip fractures is surgery due to its superior results in terms of function and mortality.2–4 However, non-surgical management would be indicated for stable hip fractures that mobilise with minimal pain,2–10 in patients with limited life expectancy, who are non-ambulatory, or in a poor baseline condition, whose comorbidities contraindicate surgery,1,2,4,10 or due to patient or family refusal of surgery.11,12 Various national registries show that between 2% and 25% of hip fractures will receive non-surgical management,6,13–16 and mortality in the first year can reach over 90% in these cases.4,17

Due to the increase in life expectancy, the number of frail elderly patients with hip fractures is increasing.9 They present with a lower vital reserve and a greater number and severity of comorbidities that contraindicate surgery,17,18 and this may increase the indication for non-surgical management.10,19 The lack of support in current clinical guidelines for opting for non-surgical management poses difficulties in preoperative decision-making.20 Most current publications focus primarily on surgical treatment of the geriatric population with hip fractures,8,9,13 including patients with a very limited life expectancy. Focusing on non-surgical management, studies include both intracapsular and extracapsular hip fractures. These series have small patient numbers and are conducted in different healthcare systems,21 making extrapolation to our population difficult. The primary objective of our study was therefore to determine mortality during hospitalisation, at 1 month, 6 months, and 1 year in patients with intracapsular hip fractures managed non-operatively. The secondary objective was to determine the frequency of non-surgical management in patients with intracapsular hip fractures and whether there was an association between mortality and certain factors.

Material and methodsA retrospective case series study was conducted based on a review of all intracapsular hip fractures admitted to our centre between January 2004 and December 2023, inclusive. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards recognised by the Declaration of Helsinki and Resolution 008430 of 1993, and was approved by the institution's ethics committee, with internal code 22/31.

Those included were patients over 18 years of age with an intracapsular hip fracture and a minimum follow-up of one year, in whom non-operative management had been decided upon. Patients with intracapsular hip fractures treated surgically; those for whom surgery was indicated but who died preoperatively; atypical fractures; periprosthetic fractures; fractures secondary to tumours, or polytraumatised patients were excluded.

The decision to choose non-surgical management was made jointly by the trauma, geriatrics, and anaesthesiology departments, in agreement with the patient and/or their family members. The reason for indicating non-surgical management was recorded. Frail elderly patients were considered to be those with one or more frailty criteria (body mass index ≤18.5kg/m2 or cachexia, poor ambulatory ability before the trauma (limited to indoor living with supports or unable to walk), ASA score of 4 or 5) or based on the clinical judgment of the attending surgeon and/or geriatrician when a limited life expectancy was considered without meeting the frailty criteria.20,22 This consisted of early sitting within 24–48h, with mobilisation as soon as possible, depending on pain involved, avoiding prolonged bed rest and/or traction. The patient remained hospitalised until their baseline medical condition was stabilised and pain controlled. The patient and their family members were taught home care, maintaining bed-chair life. Once the goals were achieved, the patient was discharged from hospital and sent home.

The patients’ medical records were reviewed individually to obtain: age, sex, ASA classification, preoperative Barthel Index (grouped according to score: total dependence <20 points, severe 20–35, moderate 40–55, and mild 60–95). Functionality was assessed before and 30 days after the fracture and classified as 1: independent mobility inside and outside the home without technical aids; 2: independent mobility inside and outside the home, with technical aids; 3: independent mobility only inside the home; 4: mobility only inside the home, with minor assistance from one person; and 5: mobility with two people or no mobility (bed-chair lifestyle). The length of stay was also recorded, defined from admission to the emergency department to hospital discharge. The place of residence prior to the fracture and the destination upon discharge were recorded, as well as the need for readmission or evaluation in the hospital's emergency department within 30 days. Finally, we studied mortality during hospitalisation, at 30 days, at 6 months, and at 1 year. We also analysed the association between mortality and certain factors such as age, sex, ASA score, Barthel Index, mobility prior to and at 30 days, place of origin, destination upon discharge, or readmission within less than 1 month.

SPSS version 25 was used for statistical analysis. Quantitative variables were expressed as medians (interquartile ranges), while qualitative variables were expressed as percentages. Comparisons between quantitative and qualitative variables were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test and the Chi-squared test, respectively. Factors associated with mortality were analysed using bivariate analysis. A two-sided significance level of .05 was set.

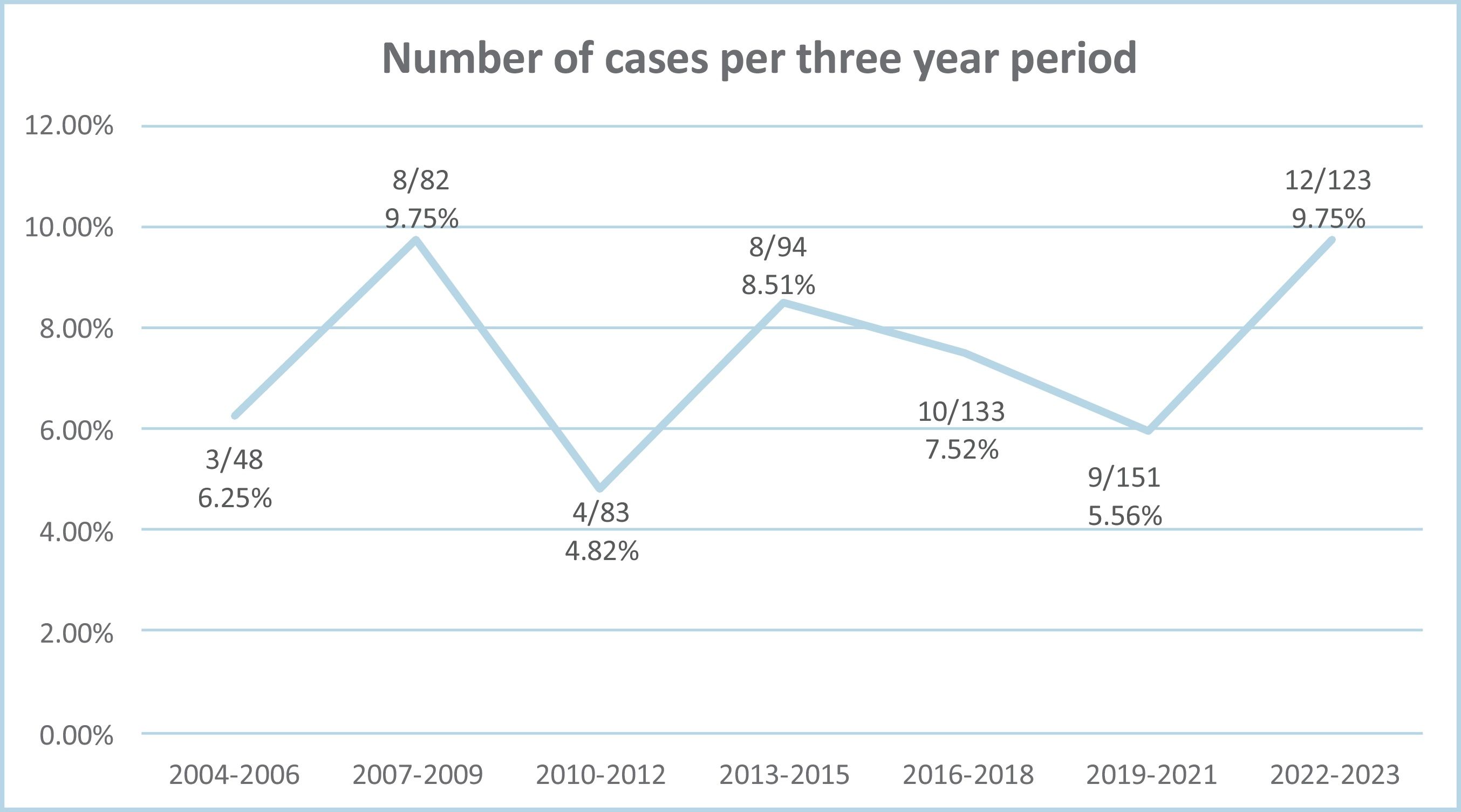

ResultsA total of 714 intracapsular hip fractures were admitted to our centre during the study period. Non-operative management was indicated in 54 patients, with a frequency of 7.56%. Of these 54 cases, two patients were excluded due to loss of follow-up, leaving a total of 52 intracapsular hip fractures analysed. Fig. 1 shows the evolution of the indication for non-operative management at our centre over the years.

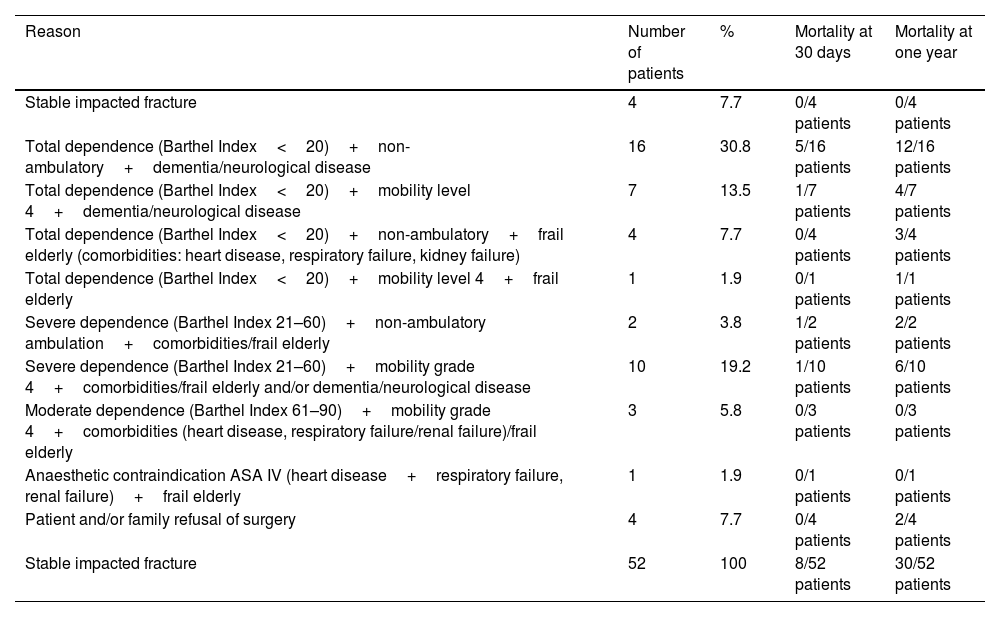

The indications for deciding on non-operative management are summarised in Table 1. Low functionality (Barthel Index <20 [total dependence]) associated with inability to ambulate and neurological disease/dementia were the most common reasons (16 patients: 30.8%). In one patient (1.9%), the anaesthesiology department contraindicated surgery due to unacceptable anaesthetic risk, mainly due to severe heart disease with mechanical heart valves. Four patients (7.7%) decided not to undergo surgery, having adequately tolerated sitting with analgesia, not wanting to assume the surgical risks, and understanding the expected functional loss outcomes.

Reason for non-surgical management of intracapsular hip fracture.

| Reason | Number of patients | % | Mortality at 30 days | Mortality at one year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stable impacted fracture | 4 | 7.7 | 0/4 patients | 0/4 patients |

| Total dependence (Barthel Index<20)+non-ambulatory+dementia/neurological disease | 16 | 30.8 | 5/16 patients | 12/16 patients |

| Total dependence (Barthel Index<20)+mobility level 4+dementia/neurological disease | 7 | 13.5 | 1/7 patients | 4/7 patients |

| Total dependence (Barthel Index<20)+non-ambulatory+frail elderly (comorbidities: heart disease, respiratory failure, kidney failure) | 4 | 7.7 | 0/4 patients | 3/4 patients |

| Total dependence (Barthel Index<20)+mobility level 4+frail elderly | 1 | 1.9 | 0/1 patients | 1/1 patients |

| Severe dependence (Barthel Index 21–60)+non-ambulatory ambulation+comorbidities/frail elderly | 2 | 3.8 | 1/2 patients | 2/2 patients |

| Severe dependence (Barthel Index 21–60)+mobility grade 4+comorbidities/frail elderly and/or dementia/neurological disease | 10 | 19.2 | 1/10 patients | 6/10 patients |

| Moderate dependence (Barthel Index 61–90)+mobility grade 4+comorbidities (heart disease, respiratory failure/renal failure)/frail elderly | 3 | 5.8 | 0/3 patients | 0/3 patients |

| Anaesthetic contraindication ASA IV (heart disease+respiratory failure, renal failure)+frail elderly | 1 | 1.9 | 0/1 patients | 0/1 patients |

| Patient and/or family refusal of surgery | 4 | 7.7 | 0/4 patients | 2/4 patients |

| Stable impacted fracture | 52 | 100 | 8/52 patients | 30/52 patients |

Mortality at 30 days and one year is also detailed according to the different indications.

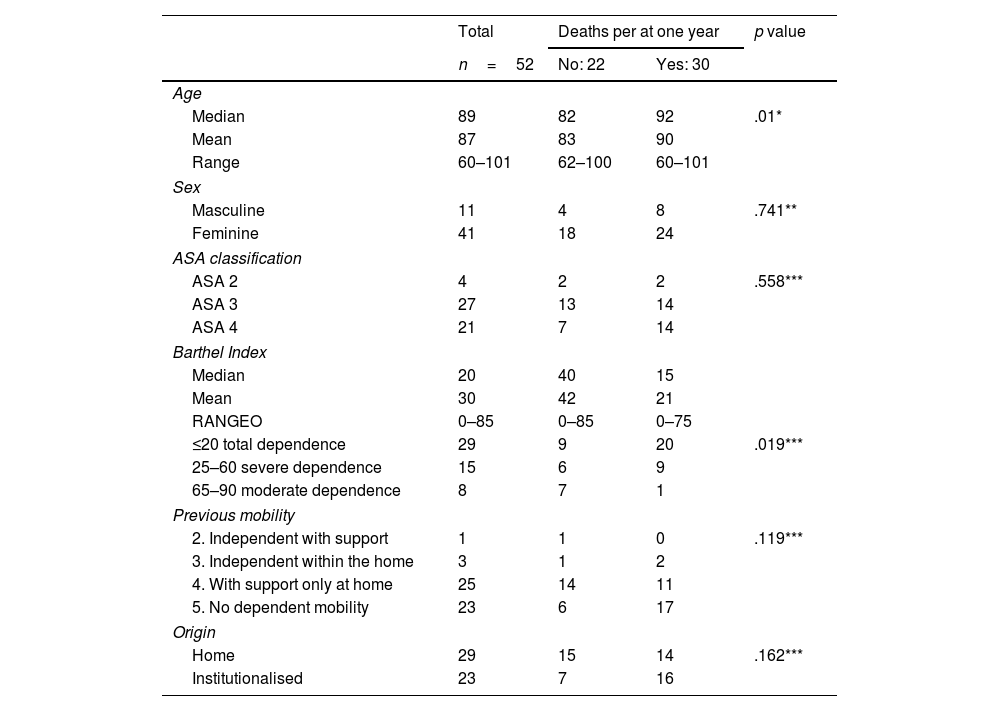

Table 2 describes the characteristics of the patients included in the study prior to the fracture. The mean length of stay was 8.3 days (range: 0–58 days, median: 5.7 days). Upon discharge, 82.7% (43/52) returned to their place of origin, 5 patients (9.6%) were referred to intermediate-stay facilities, one patient (1.9%) changed residence to a nursing home, and 3 patients (5.8%) died during their stay. Twenty-six point nine per cent (14/52) of the patients presented to the emergency department or required hospital readmission within the first 30 days after discharge. Four patients (7.7%) underwent surgery: two cases due to secondary displacement of a stable fracture and two cases due to pain and poor tolerance to conservative management. Three partial arthroplasties were implanted; none of them had died within one year of surgery. One total hip arthroplasty was complicated by episodes of dislocation, requiring two further surgeries for component replacement due to instability, and the survival rate was higher than one year after the fracture.

Patient characteristics prior to intracapsular hip fracture. Comparative study of one-year mortality and different factors.

| Total | Deaths per at one year | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=52 | No: 22 | Yes: 30 | ||

| Age | ||||

| Median | 89 | 82 | 92 | .01* |

| Mean | 87 | 83 | 90 | |

| Range | 60–101 | 62–100 | 60–101 | |

| Sex | ||||

| Masculine | 11 | 4 | 8 | .741** |

| Feminine | 41 | 18 | 24 | |

| ASA classification | ||||

| ASA 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | .558*** |

| ASA 3 | 27 | 13 | 14 | |

| ASA 4 | 21 | 7 | 14 | |

| Barthel Index | ||||

| Median | 20 | 40 | 15 | |

| Mean | 30 | 42 | 21 | |

| RANGEO | 0–85 | 0–85 | 0–75 | |

| ≤20 total dependence | 29 | 9 | 20 | .019*** |

| 25–60 severe dependence | 15 | 6 | 9 | |

| 65–90 moderate dependence | 8 | 7 | 1 | |

| Previous mobility | ||||

| 2. Independent with support | 1 | 1 | 0 | .119*** |

| 3. Independent within the home | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| 4. With support only at home | 25 | 14 | 11 | |

| 5. No dependent mobility | 23 | 6 | 17 | |

| Origin | ||||

| Home | 29 | 15 | 14 | .162*** |

| Institutionalised | 23 | 7 | 16 | |

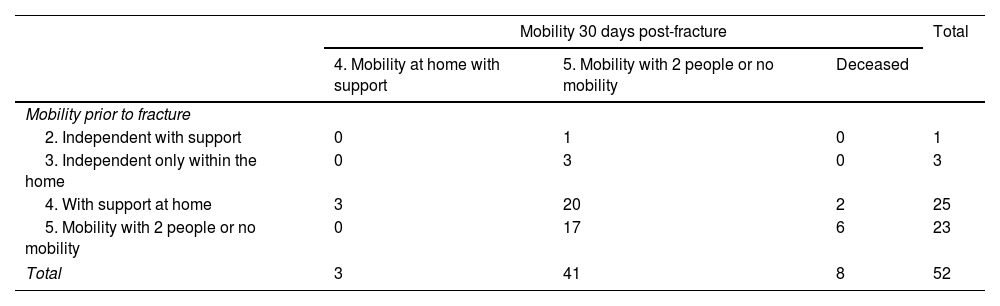

Prior to the fracture, 44.2% (23/52) were non-ambulatory. At 30 days, a loss of mobility was observed in 46.1% (24/52) of the patients. Finally, after non-surgical management of the fracture, 78.8% of the sample (41/52) were non-ambulatory (Table 3). Despite the numerical differences, no statistically significant differences were found (p=.344). An attempt was made to determine whether there was a correlation between age or hospital stay and loss of functionality at one month (Kruskal–Wallis test with p=.627 and p=.470, respectively), but no statistically significant differences were found.

Mobility prior to intracapsular hip fracture and mobility 30 days post-fracture.

| Mobility 30 days post-fracture | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4. Mobility at home with support | 5. Mobility with 2 people or no mobility | Deceased | ||

| Mobility prior to fracture | ||||

| 2. Independent with support | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 3. Independent only within the home | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| 4. With support at home | 3 | 20 | 2 | 25 |

| 5. Mobility with 2 people or no mobility | 0 | 17 | 6 | 23 |

| Total | 3 | 41 | 8 | 52 |

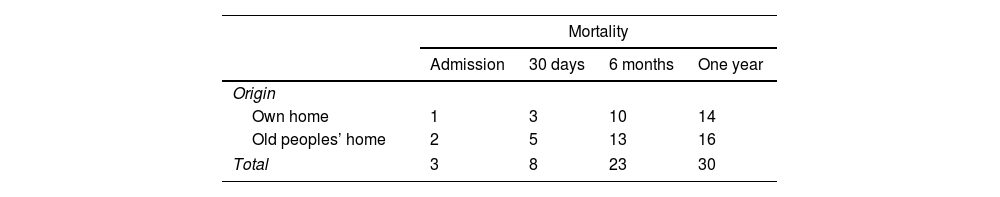

Regarding mortality, 3 patients (5.8%) died during hospitalisation. At 30 days, 8 patients had died (15.4%), at 6 months the mortality rate rose to 23 patients (44.2%), and in the first year, 30 patients (57.7%) died. Table 1 summarises the 30-day and 1-year mortality rates with respect to the indication for non-surgical management, and Table 4 summarises the distribution of deaths according to place of origin. The association between mortality and certain factors was analysed (Table 2), and an increase in mortality was observed with increasing patient age, with a mean age for deceased patients of 89.7 years compared with 83 years for those who survived one year after the fracture (Student's t-test p<.01). It was observed that both the Barthel Index (Chi squared p=.019) and mobility at 30 days after the fracture (Chi squared p=.006) are variables that are also associated with increased mortality at one year, with no significant differences being found in the rest of the parameters studied (sex, ASA, previous mobility, place of origin, destination at discharge or readmission in less than one month).

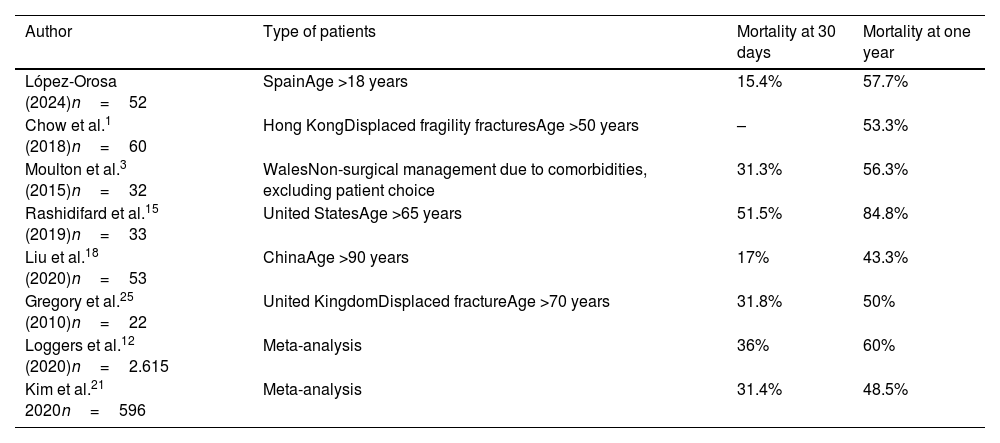

DiscussionThis study retrospectively analysed the mortality rate associated with non-operative management in patients with intracapsular hip fractures at a single centre. It showed a mortality rate at admission of 5.8%, 15.4% at 1 month, 44.2% at 6 months, and 57.7% within the first year after the fracture. However, few studies reflect the mortality rate of hip fractures with non-operative management, and these vary greatly, with in-hospital mortality rates ranging from 3.5% to 28.6%16,21,23; 1-1 month mortality rates from 5%7 to 87%17; 26%7 to 94%20 at 6 months; and 1-year mortality rates from 18.7%24 to over 95%17,22. This is due to the heterogeneity that exists between the studies and samples analyzed: series with only frail patients,17 series that include healthy patients,4 or only patients over 90 years of age,18 national registries of different health systems,13 with different medical-surgical resources (rural population with difficult hospital access5 and different economic resources12), populations from different cultures (perception that the elderly cannot tolerate surgical stress23 or fear/rejection of the patients themselves to undergo surgery and its complications11,17,23), different types of fractures included in the study: displaced or non-displaced fractures, intracapsular and extracapsular, whose surgical treatment, complications and rehabilitation are totally different. This heterogeneity makes comparison between studies difficult and makes it difficult for us to estimate the value of our results. If we focus on studies that only include intracapsular hip fractures, we observe a one-year mortality rate ranging from 43.3% to 84.8%1,3,15,18,25 (Table 5). In two meta-analyses, the 30-day mortality rate ranges from 31.4% to 36%, and the one-year mortality rate ranges from 48.5% to 60%.2,21

Comparison of mortality at one month and one year between different studies in which non-surgical management of intracapsular hip fractures was performed.

| Author | Type of patients | Mortality at 30 days | Mortality at one year |

|---|---|---|---|

| López-Orosa (2024)n=52 | SpainAge >18 years | 15.4% | 57.7% |

| Chow et al.1 (2018)n=60 | Hong KongDisplaced fragility fracturesAge >50 years | – | 53.3% |

| Moulton et al.3 (2015)n=32 | WalesNon-surgical management due to comorbidities, excluding patient choice | 31.3% | 56.3% |

| Rashidifard et al.15 (2019)n=33 | United StatesAge >65 years | 51.5% | 84.8% |

| Liu et al.18 (2020)n=53 | ChinaAge >90 years | 17% | 43.3% |

| Gregory et al.25 (2010)n=22 | United KingdomDisplaced fractureAge >70 years | 31.8% | 50% |

| Loggers et al.12 (2020)n=2.615 | Meta-analysis | 36% | 60% |

| Kim et al.21 2020n=596 | Meta-analysis | 31.4% | 48.5% |

The preferred treatment for intracapsular hip fractures according to international guidelines, such as the NICE guidelines, is surgical,3,12 with the mortality rate in these cases ranging from 6.6% to 48.2%.1,3,9,12,22,23,25,26 The mortality rate with surgical management is lower than with non-surgical management.3,7,9,21,23,26 However, there are publications,10,25 including a Cochrane review,27 in which no differences were found in the mortality rates during the first year between both treatments. Furthermore, it has been seen that in certain groups of patients, surgical treatment also records high mortality, especially if it is delayed more than 48h,9 such as institutionalised patients (36% at 6 months6), with dementia (55% at 6 months,12 75% at 1 year25) or nonagenarians, where with 95% surgical management, a one-year mortality rate ranging from 46% to 51% occurs.7 Indeed, it was expected that with non-surgical management we would obtain a high mortality rate, since fragile patients with significant comorbidities (ASA ≥3),21 who were non-ambulatory, with low functional capacity (Barthel <80 points) and dementia were selected, all of them being risk factors for mortality,2,5,8–10,15,22,28 and the likelihood of death was present regardless of the type of management. This implies a selection bias, since more patients die because they were already going to do so due to their frailty/comorbidities. It is likely that they will not die because they do not undergo surgery, or the opposite may occur: they do not undergo surgery because they will die, although we cannot confirm this either, since we do not have statistical elements to confirm it and a prospective study would be needed to test it as a hypothesis. In elderly patients, hip fracture is sometimes a symptom of a fragile state of health and, therefore, often the beginning of an inevitable cascade of collapse at the end of life, with mortality depending more on the patient's previous general condition than on the management of the fracture itself.8,20 However, there are publications in which non-surgical management itself is considered a risk factor for mortality,19,20 presenting a risk of death 4 times higher at 30 days and 1 year after the fracture than with surgical treatment.21,23

The main objectives for surgical intervention in intracapsular hip fractures in older patients are the recovery of function and improvement of quality of life.11,29 There are no consensus criteria for the non-operative management of these patients. Non-surgical management is primarily indicated in patients with significant comorbidities; with a high risk of perioperative mortality despite adequate medical optimisation4,5,12,23,25,26; who were non-ambulatory prior to the fracture, and/or who have low functional capacity for daily life activities.21,26 These factors render surgery ineffective or contraindicated by the anaesthesia team,2,4,6,22 or rejected by the patient or their family.4,17,26 Dementia plays a significant role in the decision to pursue conservative management, both for the medical team and the family. In recent literature, up to 73% of patients diagnosed with dementia opted for non-surgical management22 since improvement or recovery to their previous state was not expected. In our case, 33 patients (63.5%) presented some degree of dementia prior to the fracture. Furthermore, dementia has been identified as a risk factor for early mortality after a hip fracture,2,7 and, as already mentioned, can present with high mortality despite surgery.12,17,25 Therefore, the decision to opt for non-operative management should be made in consultation with geriatricians, traumatologists, and anaesthesiologists,2,10,12,25,29 along with the patient and family members, using various functional, quality of life, and intraoperative mortality scales. In our case, we used the ASA classification, the Barthel Index, and prior ambulatory ability. A medical history of dementia or neurological disease also played an important role, although other specific scales could be used, such as the Nottingham Hip Fracture Mortality Scale or the EuroQoL-5 for quality of life/functionality.

There is limited literature on the non-surgical management of hip fractures, with reported frequencies ranging from 2.3% to 61%.2,4,6,7,10,11,13,14,17,18,22,23 This very wide range is due to the considerable variability among the series and national registries in which the studies were conducted. Comparisons between published studies are difficult, although there are series focused on frail patients over 70 years of age that report high rates of non-surgical management (45%–61.6%7,18,20). In Spain, a cohort study from La Paz Hospital in Madrid28 was published, reporting a non-surgical management rate of 4.5%, which is lower than ours. Although it includes extracapsular hip fractures, the article focuses on surgical outcomes and does not specify the types of fractures that received non-surgical management. The selection of only intracapsular fractures is what distinguishes our series from most publications, and this is important given that intracapsular fractures, as indicated by the national registry, represent approximately 40%13 of hospitalised hip fractures. Had we also recorded extracapsular fractures, and considering that surgical treatment is usually preferred for these,3 our overall non-surgical management rate for hip fractures would likely have decreased.

In current practice, over 95% of all proximal femur fractures are treated surgically.6,20 However, we do not believe that the indication for non-surgical management will decrease in the future. It may remain stable6 or, on the contrary, foreseeably increase,10 since the population with hip fractures is increasingly frail with severe comorbidities. This correlates with the choice of non-surgical management1 and severe comorbidities may in themselves prevent surgery.19,29 It is important to determine what happens to patients who do not undergo surgery in order to improve their outcomes, advocate for multidisciplinary follow-up and even palliative care if necessary.

There is increasing awareness, particularly in other countries, of the value of non-surgical management within a palliative care context as a valid option for frail elderly patients with hip fractures,12,14,17,20 and as an alternative to surgery6,22 especially in the final stages of life. In some studies, up to 46% of patients voluntarily choose non-surgical management without a medical justification17 Loggers et al.20 demonstrated that patients who opt for non-surgical palliative management experience a quality of life that is no inferior to that of those who choose surgery during the terminal phases of life, with an approach more focused on the patient's well-being and pain management than on functional recovery. Thus, palliative management appears to be a viable strategy focused on the quality of death, rather than considering it a treatment failure. Given the annual mortality rate, the decision not to “prolong life unnecessarily” becomes plausible, as does the possibility that the patient/family may not wish to assume the risks, complications, and postoperative recovery of surgery. This is especially true when the patient/family is informed and able to choose, while always retaining the option of undergoing surgery if desired. It is understood that non-surgical management in a palliative context is not curative, and patients are likely to die within weeks of a hip fracture.22 At this point, various factors come into play in the decision-making process: cultural beliefs, legislation, ethics,21,26 and the capacity to make decisions when under duress (a time when risks and discomforts are typically perceived more than the benefits of treatment,14,17,20 further complicating the decision. However, we do not yet encounter this conflict in our setting.

We wish to emphasise the importance of pain management, which is often inadequate in these patients, and its administration20 is a factor in end-of-life care that should be improved.

Regarding other risk factors for mortality after a hip fracture, in line with other published studies, we observed a significant association in our series between mortality and a low Barthel Index (p=.019),9 as well as with age (p<.01), with older patients dying within the first year.1,9 Although some studies associate the number of comorbidities or ASA classification with the risk of mortality with non-surgical management,21,25 reaching a 30-day mortality rate above 65% in frail/ASA IV patients,3,4,17 we found no significant differences. Another risk factor mentioned in previous studies is the place of origin,12,28 noting that institutionalised patients have a 1.97 times greater risk of mortality in hip fractures with surgical treatment.11 We have not found a statistical association between origin and mortality, although those from residential care have higher mortality at discharge, at one month, at 6 months and at one year.

Non-surgical management involves decreased functionality and immobility, which is associated with medical complications10,12,21 and, therefore, increased mortality (p=.006). A key area for improvement is the promotion of an orthogeriatric/multidisciplinary approach15,28–30 in both inpatient and outpatient settings, which has demonstrated improvements in hospital stay and morbidity and mortality.4,29,30 Implementation of this approach varies depending on the hospital, population, and healthcare system or country, and sometimes only 3.5% of cases benefit from it.1 In our case, the problem arises upon hospital discharge, where the patient is followed up by their primary care physician, with periodic check-ups in the first year at trauma clinics, thus missing the multidisciplinary management that their situation requires. Thus, despite starting with patients who had poor function prior to the fracture, we observed that functionality worsened even further. In our case, of 29 patients with some pre-fracture ambulatory capacity,24 82.7% became non-ambulatory, which implies greater difficulty in their care, a higher expenditure of resources, and, to a large extent, readmissions or reassessment in hospital emergency departments. Our readmission rate in the first 30 days was lower than that reported in other studies (34.4%–63%)7,12,26 although comparison is again difficult since we did not record the reason for these readmissions. We are in line with published findings regarding conversion to surgery, which ranges from 2.3% to 16%.3,4,10,20 These readmission rates, in our opinion, could decrease with multidisciplinary follow-up that includes specialised nursing care and improved access to pain management units. This would also contribute to a reduction in mortality, as already indicated in other articles.1,3,4,20 It would be interesting to investigate, through prospective studies, whether outpatient care (types and resources) influences the outcomes of non-surgical management of hip fractures, or if there are other factors not controlled for in our study.

Our study has limitations. Firstly, those inherent to any retrospective study. Therefore, prospective, comparative studies with surgical treatment and/or multicentre studies on this topic would be valuable. Secondly, selection bias is an important factor to consider because patients opting for non-surgical management may be in a poorer condition prior to injury, which could increase mortality. Frailty has been linked to higher mortality rates in more fragile patients,12 although we found no correlation between ASA classification and one-year mortality.7,17,18 Finally, beyond the prior diagnosis in their medical history, the study did not assess patients’ cognitive status or associated medications, characteristics that correlate with the indication for non-surgical management and the prognosis of hip fractures.1,7

Therefore, the absence of functional or quality-of-life scales, the retrospective descriptive study design with a small sample size due to the exceptional nature of conservative treatment, necessitates that the results be interpreted with caution. It is not possible to confirm or rule out the existence of significant differences, particularly regarding the association between mortality and other variables studied.

It is worth pointing out that our series, unlike others, is homogeneous: it only includes patients with intracapsular hip fractures from a single centre/healthcare system. It is also interesting because we have not found similar series in our region, and we recorded one-year mortality, a data not mentioned in the national hip fracture registry.13

Therefore, considering that one-year mortality for non-surgical management is high (57.7%), and given that the patients for whom this approach is typically indicated are frail, multimorbidity elderly patients at high surgical risk with low pre-existing functional capacity (limited ambulation, low Barthel Index, and dementia), we must be highly punctilious regarding its indication, evaluating functionality, quality of life, and mortality risk with different scales (Barthel, EuroQoL-5, Nottingham test, etc.). We must also improve multidisciplinary outpatient follow-up for these non-surgical patients or consider alternative palliative care focused on the patient rather than functional outcomes, without resorting to therapeutic obstinacy, as is occurring in neighbouring countries. It would be advisable to conduct prospective, comparative and/or multicentre studies to determine the best treatment option for each patient and their families.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

FundingThe authors declare that they received no specific funding or assistance from public, commercial, or non-profit agencies for this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare regarding the results of this study.