Prosthetic joint infections (PJI) are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, underscoring the importance of identifying the related risk factors. The objective of the present study was to evaluate whether environmental factors were correlated with an increase in PJI.

Material and methodRetrospective cohort study of 1847 consecutive hip and knee prosthesis surgeries performed at a single center over a 10-year period. All patients who underwent surgery during this period were included, with a minimum follow-up of 2 years. The association between infection cases and environmental temperature and humidity was analyzed for both the day of surgical intervention and the week following the procedure.

ResultsSixty-three cases of infection (3.4%) were identified. No statistically significant differences were observed in the infection rate according to the month (p=0.13) or season (p=0.42) in which the surgery was performed. Furthermore, no significant association was found between the incidence of PJI and the average temperature or humidity on the day or week following the prosthesis implantation.

ConclusionsEnvironmental temperature and humidity do not influence the incidence of PJI in regions with an oceanic climate. The increase in PJI according to environmental conditions is primarily observed in large-scale studies based on national registries.

Las infecciones de prótesis articulares (IPA) están asociadas a una significativa morbimortalidad, siendo crucial identificar sus factores de riesgo. El objetivo de este estudio es evaluar si los factores ambientales se asocian a un aumento de las IPA.

Material y métodoEstudio de cohortes retrospectivo de 1.847 intervenciones consecutivas de prótesis de cadera y rodilla realizadas en un único centro hospitalario durante un periodo de 10 años. Se incluyeron todos los pacientes intervenidos en este periodo, con un seguimiento mínimo de 2 años. Se analizó la asociación de los casos de infección y las variables ambientales (temperatura y humedad) registradas el día de la intervención quirúrgica y la semana siguiente a la operación.

ResultadosSe identificaron 63 casos de infección (3,4%). No se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en la tasa de infecciones según el mes (p=0,13) o la estación (p=0,42) en que se realizó la intervención quirúrgica. Asimismo, no se encontró una asociación significativa entre la incidencia de IPA y la temperatura media o la humedad relativa del día de la implantación protésica o la semana siguiente a la intervención.

ConclusionesLa temperatura y humedad ambiental no influyen en la incidencia de IPA en regiones con clima oceánico. La asociación entre el aumento de IPA y las condiciones ambientales se observa mayoritariamente en estudios de gran escala basados en registros nacionales.

Prosthetic joint infections (PJI) are among the most common healthcare-associated infections1 and the leading cause of morbidity after surgery.2 They result in increased readmission rates,3 length of hospital stay, and healthcare costs.4 Mortality rates following PJI exceed those of the five most common cancers, at up to 5% postoperative mortality per year.5,6

The seasonal distribution of several types of infection is well documented. Clostridium difficile infections show a peak incidence in the winter and spring months,7 while peripheral bacteraemia,8 cellulitis,9 and urinary tract infections10 predominate in the summer months. PJI are more controversial. Some studies report an increase in the incidence of infections following surgery in summer,11–14 others find no difference in seasonal distribution. Determining whether this variable is associated with an increase in the incidence of PJI is crucial in assessing what measures should be taken to reduce the rate of infection.

The main objective of this study was to determine whether there is a higher incidence of PJI during the summer months. As a secondary objective, we analysed a potential association with environmental variables such as temperature or humidity.

Material and methodA retrospective cohort study of 1869 consecutive planned knee and hip replacement operations performed between January 2010 and December 2019 at a single hospital centre. Both primary and revision total knee replacement (TKR) and total hip replacement (THR) procedures performed during this 10-year period with a minimum follow-up of 2 years were included. The aim was to achieve the largest possible sample size because of the low incidence of PJI and the consequent difficulty in obtaining a sufficient number of cases to draw robust conclusions. Procedures performed as treatment for fractures were excluded. Of the 1869 patients initially included in the study, 22 were excluded due to lack of information on infection status during follow-up (missing data). These were all patients who did not meet the minimum follow-up criterion of 2 years. The final sample size was 1847 cases.

In all cases, antibiotic prophylaxis was administered according to the centre's protocol, consisting of a preoperative dose of 2g of cefazolin and 3 doses of 1g for 24h postoperatively. A second dose of cefazolin was given if the surgery took longer than 2h. In patients with a history of allergy, clindamycin 600mg was administered in each dose. The surgical field was prepped with alcoholic chlorhexidine.

Data were obtained directly from the patients’ medical records. Joint prosthesis infection was defined according to International Consensus Meeting (ICM) criteria.15 The diagnosis was confirmed if one major criterion or three minor criteria were met. The type of infection was classified as chronic, acute, haematogenous, or positive intraoperative cultures (PIOC) according to the Tsukayama classification.16

Data for environmental variables were obtained from the meteorological station of the municipality where the health centre is located, accessible through the Euskalmet online database. The mean temperature on the day of surgery was recorded in degrees Celsius (°C), while the humidity value was obtained as relative humidity (%). The mean temperature and humidity during the first week after surgery were also analysed. The seasons were defined by quarter, with winter as T1 (January, February, March), spring as T2 (April, May, June), summer as T3 (July, August, September), and autumn as T4 (October, November, December).

Continuous variables are presented as means and standard deviations, while categorical variables are presented as frequencies and percentages (%). Continuous variables were analysed using Student's t-test for independent samples, while the χ2 test was used for categorical variables. The quarter variable was analysed using the χ2 test for trend. p-Values <.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with R 4.3.1 software.

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Gipuzkoa Health Region, in accordance with Law 14/2007 on Biomedical Research, the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, and other applicable ethical principles. The article follows the guidelines for communication of observational studies proposed by the STROBE initiative.

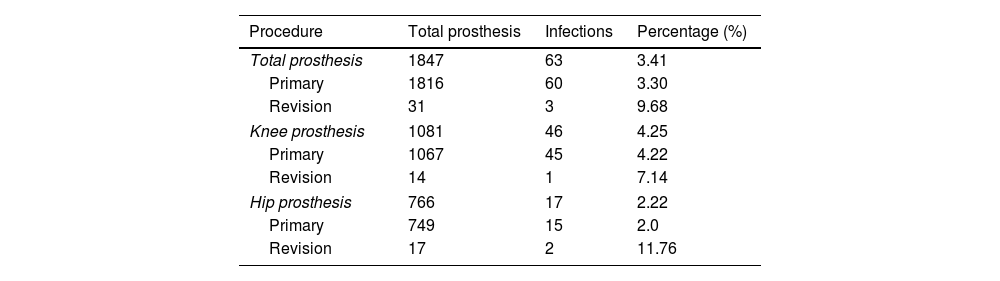

ResultsA total of 63 JPI were identified, representing 3.4% of cases (Table 1). Of these, 40 were classified as acute infections, 15 as chronic, 7 as haematogenous, and one case of PIOC was observed. Therefore, the incidence of acute PJI was 2.2%, 2.6% in TKR, and 1.6% in THR. A significantly higher rate of infection was observed in TKR than in THR (p=.018). The age of the patients on the day of surgery was 70.3±9.3 years. Of the patients, 51% were female and 49% were male. Regarding laterality, 54% were right sided and 46% were left sided.

Incidence of infections according to the type of prosthesis used.

| Procedure | Total prosthesis | Infections | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total prosthesis | 1847 | 63 | 3.41 |

| Primary | 1816 | 60 | 3.30 |

| Revision | 31 | 3 | 9.68 |

| Knee prosthesis | 1081 | 46 | 4.25 |

| Primary | 1067 | 45 | 4.22 |

| Revision | 14 | 1 | 7.14 |

| Hip prosthesis | 766 | 17 | 2.22 |

| Primary | 749 | 15 | 2.0 |

| Revision | 17 | 2 | 11.76 |

No statistically significant differences were found in the incidence of infection according to the month (p=.13) or season (p=.42) in which the surgical procedure was performed (Fig. 1 and Table 2). Similarly, no significant association was found between the incidence of infection and the average temperature or humidity on the day of prosthetic implantation or the average values during the week following surgery (Table 3).

Infection rate according to the month of surgery and the season of surgery.

| Month | Total prosthesis | Infections | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| January | 175 | 7 | 4 |

| February | 174 | 6 | 3.45 |

| March | 165 | 8 | 4.85 |

| April | 145 | 10 | 6.90 |

| May | 177 | 3 | 1.69 |

| June | 142 | 5 | 3.52 |

| July | 110 | 5 | 4.54 |

| August | 119 | 1 | .84 |

| September | 127 | 6 | 4.72 |

| October | 199 | 8 | 4.02 |

| November | 186 | 3 | 1.61 |

| December | 128 | 1 | .78 |

| Season | Total prosthesis | Infections | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1: winter | 514 | 21 | 4.09 |

| T2: spring | 464 | 18 | 3.88 |

| T3: summer | 356 | 12 | 3.37 |

| T4: autumn | 513 | 12 | 2.34 |

When the analysis was stratified by type of prosthesis (analysing hips only or knees only) and type of surgery (primary vs. revision), no significant associations were found between the infection rate and the day of surgery or the meteorological variables. The aetiology of the 31 revision cases included in the study was aseptic loosening in 17 cases, infection in 8 patients, polyethylene insert wear in 3, instability in 2, and stiffness in 1. Two of the three cases that presented with septic arthritis after revision surgery were operated on with a diagnosis of JPI, while the third case required revision surgery due to aseptic mobilisation. The higher rate of infection in revision surgery (9.7%) compared with primary surgery (3.3%) did not reach statistical significance (p=.15). However, infections were associated with significantly longer operating times (p=.0014).

DiscussionJPI cause significant morbidity and mortality in patients2 and are a substantial economic burden for healthcare systems.4 Although numerous risk factors have been identified over the past decades,17 there are still many uncontrolled aetiological variables. The influence of climatological factors on the incidence of JPI remains controversial, with previous studies producing inconsistent results regarding the association between temperature, humidity, and infection rates.

Various theories have been proposed as to the mechanism by which environmental factors influence infection. Commensal organisms, such as staphylococcal species, multiply under optimal conditions of humidity and temperature until they reach levels that increase the risk of infection.18 This theory has been supported by the observation that high levels of bacteria can be found in certain anatomical locations with higher temperatures.19 In the health centre studied, the temperature of the operating theatre is closely controlled, but there is no air conditioning in the rooms where patients stay for an average of 6 days. Therefore, room temperature is highly dependent on environmental conditions and could favour the proliferation of skin microbiota. Thus, it was hypothesised that the months with higher average temperatures might have a higher incidence of JPI. However, the present study did not show a significant association between these variables.

Table 4 summarises the characteristics of the different studies that have analysed the association between JPI and ambient temperature. It is noteworthy that most of the studies that found significant associations were based on large samples from national registries in Switzerland,13 the United States,20 and Australia.14 In the latter, the influence of climate factors was only observed in the tropical geographical area, suggesting that the effect of climate may only be relevant in certain climatic environments. Studies with smaller samples, usually limited to a single hospital centre, are subject to the peculiarities of the local climate. To our knowledge, only one single-centre study has shown an association between ambient temperature and the incidence of JPI.14 This study was conducted in Philadelphia (USA), with a continental climate and a mean temperature difference of 27.6°C between the coldest and warmest month. In contrast, the present study is located in Irun, with an oceanic climate and a seasonal temperature variation of only 12.2°C. This difference suggests that the seasonal influence on the incidence of infection could be more pronounced in geographical areas with more extreme weather conditions in each season, while the conclusions of our study would be applicable to areas with an oceanic climate. With regard to relative humidity, the values recorded at the site of the study do not vary according to the season, with a difference of only 5% between the wettest and driest months (74% vs. 79%).

Literature review of studies analysing the association between JPI and environmental factors.

| Authors | Influence of temperature | n | Location | Mean minimum T | Mean maximum T | Temperature difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iriberri et al. | No | 1847 | Irun | 7.6 | 19.8 | 12.2 |

| Kane et al.12 | Yes | 750 | Philadelphia | −6.7 | 20.9 | 27.6 |

| Damonti et al.13 | Yes | 486.000 | Switzerland | |||

| Parkinson et al.14 | Yes | 219.983 | Australia | |||

| Anthony et al.20 | Yes | 760.283 | USA | |||

| Giambelluca et al.23 | No | 3696 | New Orleans | 12.4 | 27.8 | 15.4 |

| Malik et al.24 | No | 725 | Karachi | 19.5 | 30.2 | 10.7 |

Location: location where the study was conducted. Mean minimum T: mean lowest monthly temperature. Mean maximum T: mean highest monthly temperature. n=sample size. T difference: difference between the mean lowest monthly temperature and mean highest monthly temperature.

The influence of relative humidity on the incidence of JPI has been less studied than other environmental factors such as temperature. Existing evidence suggests a possible association between high humidity and certain osteoarticular infections. In particular, an association has been documented between increased humidity and the incidence of acute haematogenous osteomyelitis in children.21 In the specific context of prosthesis infections, Armit et al.22 described a positive correlation between high infection rates and relative humidity levels above 60%. In addition, the high prevalence of JPI observed in tropical regions of Australia has been attributed, albeit indirectly, to the high humidity levels characteristic of this geographical area.14 The results of the present study do not show an influence of humidity levels on the incidence of JPI. It is important to point out that the available scientific literature on this specific relationship is limited, which underlines the need for additional studies that examine the potential influence of this environmental variable in more detail.

A limitation of this study is the potentially inadequate sample size. Although the 1869 cases represent all patients undergoing surgery in our centre over 10 years, the low incidence of JPI meant only 63 cases of infection, which is the effective sample size for the main analysis. This factor may have influenced the lack of significant differences between the infection rates of primary and revision prostheses, as well as other possible variables. The presence of significant results in studies based on national registries suggests the difficulty of drawing robust conclusions on this variable using data from a single centre. The inclusion of a heterogeneous group of patients, although necessary to maximise sample size, may have introduced confounding factors. However, the results were consistent when knee and hip prostheses, and primary and revision procedures, were analysed separately. The involvement of multiple surgeons in the procedures may have facilitated the introduction of bias, although it also helped to increase the external validity of the study.

The main aim of this study was to identify variables that might help reduce the incidence of JPI. We hypothesised that there might be an increase in the number of infections during the summer months. Confirmation of this hypothesis would have had significant implications for surgical planning, potentially benefiting patients by reducing the risk of a disabling complication such as infection. However, as we found no evidence to support this hypothesis, our results suggest that joint replacement surgery can be planned throughout the year without an apparent increase in the risk of infection due to seasonal factors.

Level of evidenceTherapeutic study (retrospective cohort study) with level III evidence.

Ethical considerationsThis study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Region of Gipuzkoa, in accordance with Law 14/2007 on Biomedical Research, the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and other applicable ethical principles.

Patients’ rights to privacy and confidentiality are guaranteed, as described in the relevant section of these regulations. We have avoided any type of identifying data in text or images in the article.

Informed consent was obtained from the patients to participate in the study and to the publication of the results in the Revista Española de Cirugía Ortopédica y Traumatología in print and electronic (Internet) format.

FundingNo external funding was received for this study.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

We would like to thank Dr Enrique Sologaistua for the impetus he provided at the beginning of this study, we would all have liked him to see the final result.