This article highlights the importance of historical knowledge in current medical training and practice, particularly in specialties such as Traumatology and Orthopedic Surgery. It criticises the increasing technologization of medicine and its growing disconnection from the humanities. The study argues that the historical study of diseases—especially so-called “crippling” diseases, like poliomyelitis and musculoskeletal tuberculosis—provides a deeper understanding of current clinical processes, enhances medical empathy, and promotes a more comprehensive and critical education.

MethodsA historiographic study was conducted on 138 medical records from the San Juan de Dios Sanatorium in Seville, spanning the years 1943–1950. Thirty-two cases related to poliomyelitis and musculoskeletal tuberculosis were analysed in depth, 9 of which underwent surgical intervention. Two cases involving subtalar arthrorisis were highlighted as examples to reinterpret past treatments using current orthopaedic knowledge.

ResultsPatients with poliomyelitis treated in the past underwent aggressive surgical procedures that, although well-intentioned, often resulted in severe deforming sequelae. Many of these patients now present with osteoarthritis, chronic pain, or deformities. Techniques such as rib arch grafting (Grice's technique) were precursors to modern methods like the calcaneal stop screw. While some procedures had long-term functional success (over 90% positive outcomes), many failed to consider the emotional and psychosocial impact on the patient.

ConclusionsThis study demonstrates that understanding the historical context of disease is essential for providing more humane, effective, and empathetic care. It advocates for the integration of the History of Medicine into the curricula of medical specialties, to avoid simplistic judgments of past practices and to recognise that medical treatments are also cultural products of their time. Historical training allows physicians to develop critical, humanistic thinking and a respectful approach to the patient's experience.

El artículo pone en valor la importancia del conocimiento histórico en la formación y práctica médica actual, especialmente en especialidades como la Traumatología y la Cirugía Ortopédica. Denuncia la creciente tecnificación de la medicina y la desconexión con las ciencias humanísticas. Se plantea que el estudio histórico de las enfermedades, en particular las denominadas «lisiantes», como la poliomielitis y la tuberculosis osteomuscular, permite comprender mejor los procesos clínicos actuales, mejorar la empatía médica y fomentar una formación más integral y crítica.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio historiográfico de 138 historias clínicas del Sanatorio San Juan de Dios en Sevilla, entre los años 1943 y 1950. Se analizaron en profundidad 32 casos relacionados con poliomielitis y tuberculosis osteomuscular, de los cuales nueve fueron intervenidos quirúrgicamente. Se destacaron dos casos de artrorrisis de la subastragalina como ejemplos para reinterpretar tratamientos pasados con los conocimientos traumatológicos actuales.

ResultadosLos pacientes con poliomielitis tratados en el pasado sufrieron intervenciones quirúrgicas agresivas que, aunque bien intencionadas, dejaron graves secuelas deformantes. Muchos de estos pacientes llegan hoy a consulta con artrosis, dolor crónico o deformidades. Las técnicas utilizadas, como el injerto de arco costal (técnica de Grice), fueron precursoras de métodos modernos como el tornillo calcáneo-stop. Se evidenció que, aunque algunas técnicas tuvieron éxito funcional (más del 90% de resultados positivos a largo plazo), muchas intervenciones no contemplaron las implicaciones emocionales y psicosociales del paciente.

ConclusionesEl estudio muestra que comprender el contexto histórico de la enfermedad es esencial para ofrecer una atención más humana, efectiva y empática. Aboga por integrar la Historia de la Medicina en el currículo de las especialidades médicas, para evitar juicios simplistas sobre prácticas del pasado y entender que los tratamientos médicos son también productos culturales de su tiempo. La formación histórica permite al médico desarrollar un pensamiento crítico, humanístico y respetuoso con la experiencia del paciente.

In terms of teaching medicine and its various specialities, new developments are given special attention, while accumulated knowledge is not considered important. Another issue is the increasing technification of medicine, which encourages students to focus excessively on biology. Our profession is becoming increasingly distant from its more humanistic aspects, or in other words, medicine is becoming isolated from the humanities and social sciences.1

The same is true of postgraduate studies. The technologisation of medicine is leading to a medical model based on diagnostic tests. The virtues of a thorough medical history based on careful questioning and an approach to patients’ psychosocial problems are being forgotten, as is the importance of the basic manual examination of patients.

Therefore, the history of medicine is useful in promoting scientific and humanistic thinking. This applies not only to undergraduates, but also to postgraduates facing a medical residency. With historical training, knowledge is perceived as a culturally constructed product of history. The limitations of reality and the possibilities for transformation and construction of new alternatives are realised, and no value judgements are made about what has been done in the past. Additionally, intellectual skills such as reasonable criticism, appropriate scepticism, healthy questioning of dogmas and faith in authoritarian views will be gained. In short, studying the history of medicine helps one to socialise within the profession.

Specialised healthcare training in Spain (the MIR system) was established in 1984 as the sole route to specialisation. Since then, responsibility for training has rested with the National Health System, which in turn delegates this responsibility to the different regional health systems. Currently, Spanish universities are not responsible for specialised training, which is guaranteed by an employment contract that the resident must provide, and by the right to receive training as set out in national programmes for each specialty.

In teaching the various specialities, and more specifically trauma and orthopaedic surgery, clinical sessions are held in which the entire department, including assistant doctors and residents, participates. During these sessions, cases are presented with supporting radiographic studies and other complementary tests, and a treatment plan is agreed upon. In our case, theoretical study of the disease must be combined with surgical skills acquired during operating sessions.

Although we recognise the value of the history of medicine in promoting scientific and humanistic thinking in undergraduate and postgraduate students alike, practical training does not explore the history of the specialty.2

With historical training, knowledge will be perceived as a culturally constructed product of history. The limitations of reality, as well as the possibilities for transformation and the construction of new alternatives, will be realised. Rather than making value judgements about what has been done in the past, medical professionals will gain intellectual skills such as reasonable criticism, scepticism, and questioning of dogmas and authoritarian views. This will help them to socialise within the profession.3

Merrell lists the reasons why the historical study of disease is necessary4:

- 1.

Knowledge of the past helps us to avoid making the same mistakes again.

- 2.

We have a strange need to find heroes and sources of inspiration in the fight against disease.

- 3.

By looking at the past, we can predict the future direction of science.

- 4.

Studying history is a lesson in humility.

- 5.

Studying history affirms the fundamental principles of medicine: providing care and concern for others and encouraging curiosity.

We will begin with a study of clinical cases dedicated to diseases that were pejoratively referred to as ‘crippling’ in the mid-20th century, or to permanent injuries. Patients presenting with serious deforming sequelae that are shown in trauma and orthopaedic surgery services currently come to the clinic. We will use these cases to demonstrate the usefulness of studying diseases in a historical context in order to understand how current knowledge of traumatology can inform treatment decisions.

Countless studies have been devoted to injuries affecting so-called ‘crippled children’, a term used during the Franco regime to describe individuals with certain bone diseases, primarily polio and musculoskeletal tuberculosis. The specialty of orthopaedic surgery may also have originated in the treatment of infantile paralysis, an epidemic which led to the establishment of specific centres for its treatment (Fig. 1). Alongside war wounds and occupational accidents, greater specialisation in surgery became necessary, a field of medicine that until well into the 20th century covered everything related to surgical disease.5

Our working group evaluated 138 medical records from the San Juan de Dios Institution (Sanatorio Nuestro Padre Jesús del Gran Poder) in Seville, dating from 1943 to 1950. This sanatorium was specifically built to treat children with bone diseases, as stated in its founding charter of 1943 (Fig. 2).

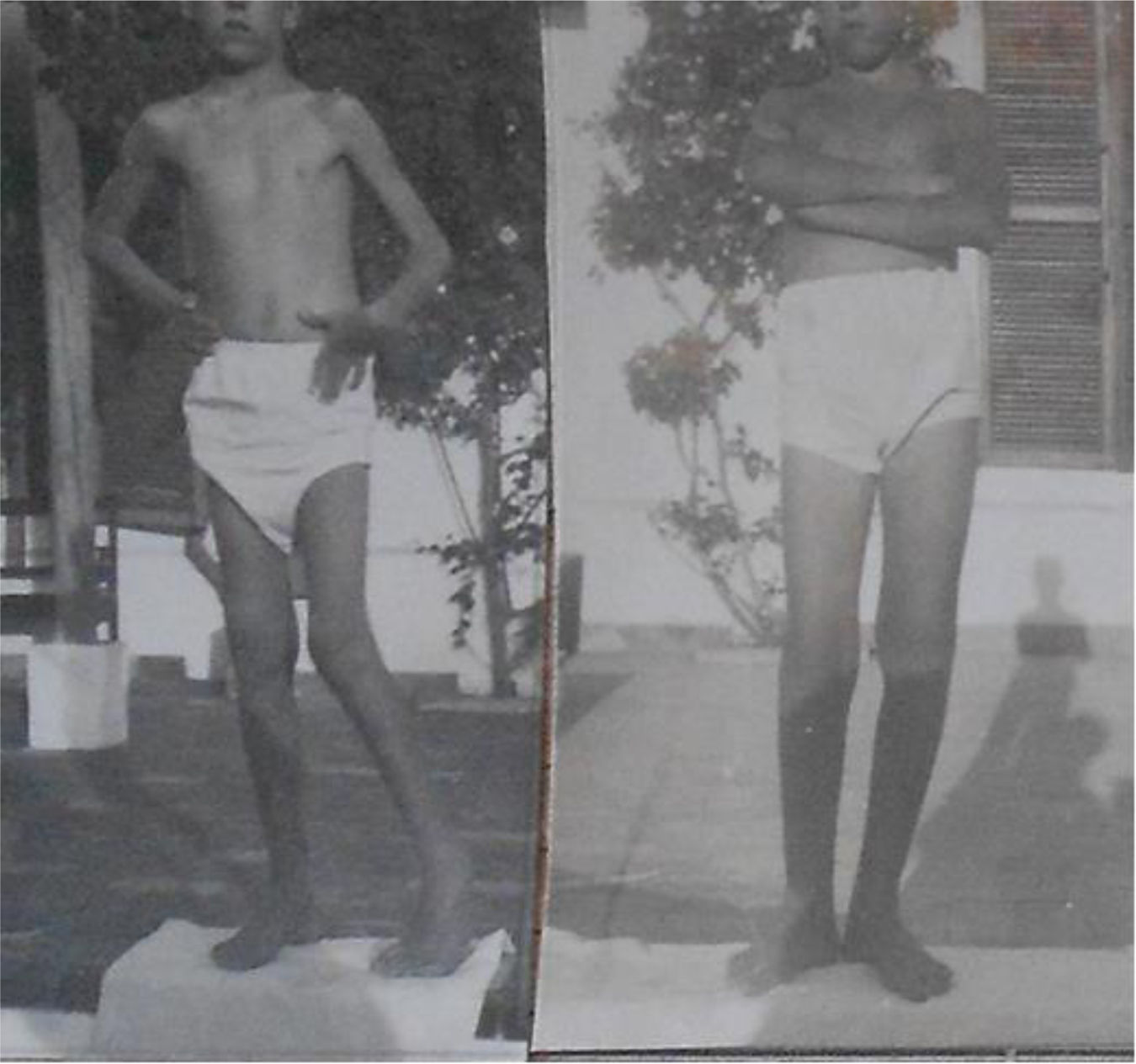

The medical records were collected in 61 envelopes, 32 of which corresponded to cases of polio or musculoskeletal tuberculosis—the ‘crippling’ diseases of the time (see Figs. 3 and 4). Nine of these 32 records corresponded to cases of poliomyelitis that underwent various surgical procedures.

We present an example of how studying a disease from a historical perspective can inform current knowledge of traumatology and help determine the best course of action in certain cases.

Results and discussionWhy are we presenting cases of ‘crippling’ diseases, and more specifically cases of polio?

It is estimated that there are currently more than 20,000 people in Spain affected by sequalae of polio and post-polio syndrome. Between the 1940s and 1970s, these individuals underwent numerous surgical procedures with unsatisfactory outcomes. They now come to our clinics seeking solutions to their functional problems and painful disorders. Due to the characteristics of the bone (atrophic and highly vulnerable to fractures), certain factors must be considered when treating these patients. They deserve special attention in terms of diagnosis, as well as in terms of synthesis and arthroplasty as therapeutic methods.6

All cases of polio recorded at San Juan de Dios in Seville underwent foot surgery, and some also underwent hip surgery. These surgeries obviously led to the patients growing up with significant deformities and degenerative joint conditions.

Due to our current lack of knowledge about the process to which polio patients were subjected, we believe that the doctors and surgeons were somewhat inexperienced. This is perceived by most of those affected, who complain about the premature judgements made by the attending physicians and their lack of understanding of patients’ fears about renewed suffering.

Of the 9 polio cases, we will focus on 2 that underwent subtalar arthrodesis for paediatric flatfoot valgus.

This specific procedure involved placing a rib graft in the tarsal sinus. This technique was developed by the orthopaedic surgeon Ladislao Gálante in the second half of the 20th century. Although synthetic implants are currently favoured over biological ones, this technique was popular and effective in correcting rearfoot valgus. It limits the displacement of the talus on the calcaneus by acting as a bone stop. It also achieved acceptable bone integration and reduced clinical deformity (see Fig. 5).

Years ago, Vaquero González published an article on the results of a similar technique, except that the graft was taken from the leg, shaped into a wedge, and inserted into the tarsal sinus. The article details the positive outcomes of Grice's technique in 50 cases treated within Professor Sanchís Olmos’ department between 1953 and 1956. They added a tendon transplant to the bone technique, usually transferring the peroneus longus to the peroneus brevis or, if this was not possible, to the base of the fifth metatarsal.7

In summary, bone grafts were used before more recent implants, which similarly aimed to correct valgus in children with flexible flat feet. The Giannini prosthesis,8 or the calcaneal stop technique, which was described in 1976 by Dr Recaredo Álvarez,9 and uses a cancellous screw in the subtalar joint as a lock, have been used to treat this problem for years. Several designs of the so-called ‘calcaneal stop screw’ have emerged throughout the history of this technique, with modifications to the screw's shape intended to avoid injury to the talar neck. Examples include the AGA screw by Aguilar Cortés and Gómez Arroyo, which is smoothed in its proximal portion and therefore not threaded on the external part of the calcaneus.10

The various arthroplasty methods have always been very well received by professionals and patients alike in the long term. Studies show that over 90% of cases have excellent outcomes,11 which means that even if subtalar osteoarthritis develops during adulthood, it is generally well tolerated.

ConclusionsAs we have discussed since the beginning of the article, studying the history of the disease can help us to recognise the social and psychological factors that should not be overlooked when considering the surgical treatment of the condition. For example, a polio patient may have undergone an average of 20 surgical procedures throughout their childhood, resulting in long periods of hospitalisation and equally painful treatments. We have selected two cases of flat feet in polio patients who were treated using the old Grice technique. This is firstly to understand the possible deformities with which they present at our clinics today, decades after the operations were performed by orthopaedic surgeons in the 1940s and 1950s, when Spain was experiencing a polio epidemic producing disabilities and fear among the population. Many interventions were ineffective due to motor deficit resulting from anterior spinal cord injury, as well as bone fragility and atrophy. However, the foot procedure successfully corrected the exaggerated valgus deformity of polio feet and achieved plantigrade support by combining techniques on soft tissues.

In our historiographical study of disease, we avoid viewing history as a series of individual discoveries. We also reject linear development in favour of the horizontal development of specialists with a practical approach. It is crucial that we understand the patient from birth until they reach us in old age. While it is important to understand how society shapes our understanding of disease, our approach to healing and the type of doctor we produce, we must not forget the humanistic side of our profession. There is no doubt that historical studies help to cultivate this aspect of our work. Although society is moving towards a type of medicine based on diagnostic testing and the technological advancement of care, which distances professionals from patients, we must remember that our profession will always be more efficient and effective if we prioritise humanisation and the entire field of knowledge surrounding it.

The history of medicine and of specific medical specialities should be included in the curricula for medical specialities. As Professor Laín Entralgo said: ‘History humanises people, makes them cultured, stimulates their imagination, and shapes them for the future’.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence v.

FundingThis research study was self-financed. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Ethical considerationsThis paper is based on a historiographical study of old medical records. The data contained within these records no longer allows for the direct identification of patients. The confidentiality of the information and current data protection regulations have been respected at all times. As the study is retrospective and documentary in nature, informed consent was not required; however, the principle of respecting the dignity of those involved has been observed.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.