Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) of the spine prevents the collapse of osteoporotic vertebral fractures (OVF) with lower complication and bleeding rates than open surgery. However, the possibility of hidden blood loss (HBL) has been recently described, referring to the loss of blood diffused into tissues and lost through hemolysis. This study aimed to estimate the postoperative impact of HBL in patients undergoing MIS for OVF.

Materials and methodsThis was a retrospective study of a series of patients who had MIS for OVF. A descriptive analysis of recorded variables was performed, and total blood volume (TBV), total bleeding (TB), HBL, and Hb drop were calculated. This was followed by a comparative analysis between HBL (<500mL vs. ≥500mL) and the variables of hospital stay and postoperative evolution. Binary logistic regression models were performed to rule out confounding factors.

ResultsA total of 40 patients were included, 8 men and 32 women, with a mean age of 76.6 years. The mean HBL was 682.5mL. An HBL greater than 500mL is found to be an independent risk factor for torpid postoperative evolution (p=0.035), while it does not predict a longer hospital stay (p=0.116). In addition, a higher HBL was observed in surgeries of greater technical complexity and longer surgical time.

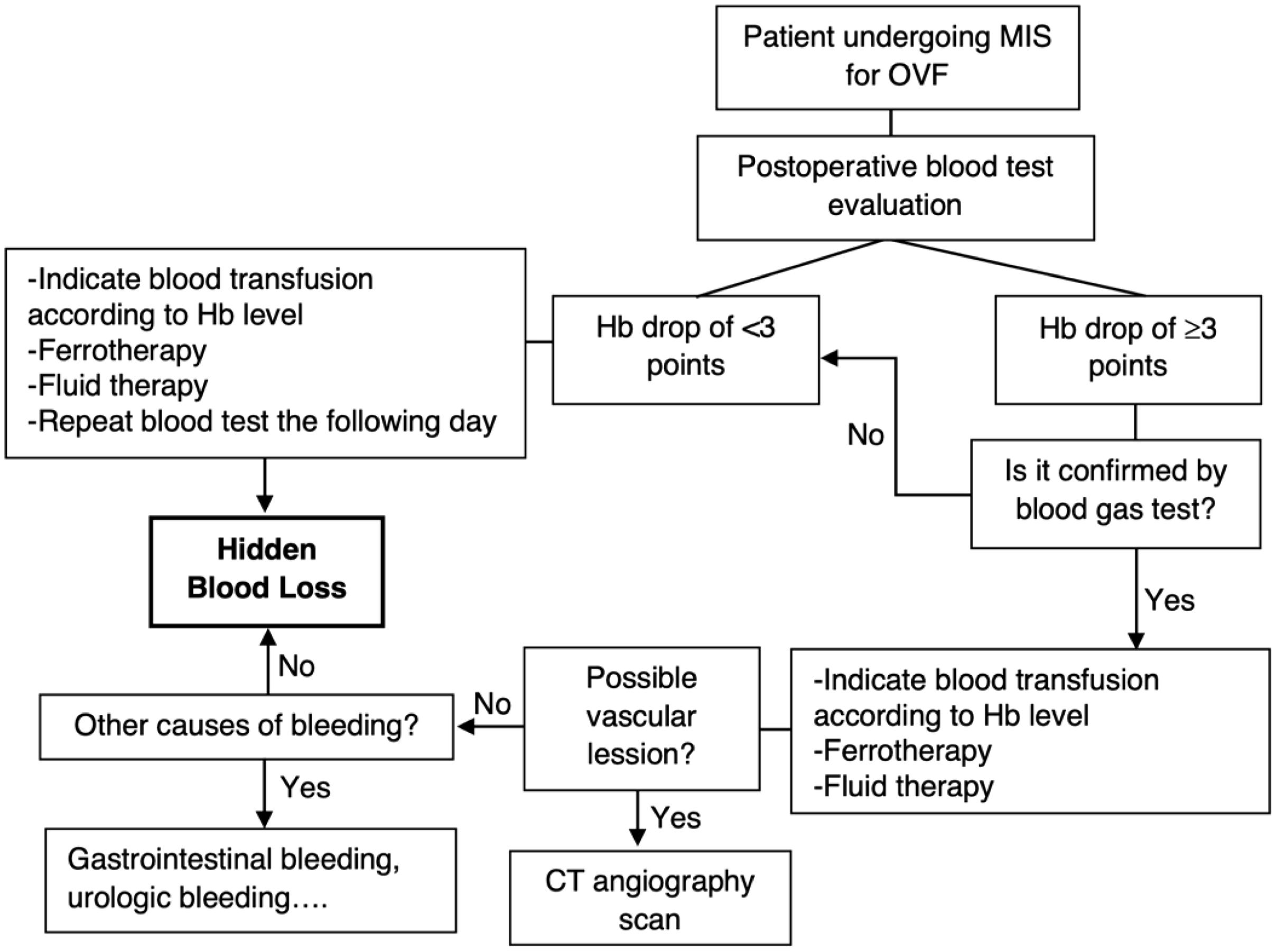

ConclusionsAlthough MIS techniques have shown less intraoperative bleeding than open surgery, HBL should be diagnosed because it is associated with a torpid evolution. The use of a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm may help minimize its impact.

La cirugía mínimamente invasiva (CMI) de columna previene el colapso de las fracturas vertebrales osteoporóticas (FVO) con menores tasas de complicaciones y sangrado que la realizada de forma abierta. Sin embargo, recientemente se ha descrito la posibilidad de sangrado oculto (SO) intraoperatorio, que hace referencia a la pérdida de sangre difundida en los tejidos, y que se da por hemólisis. Se pretende estimar el impacto del SO en pacientes sometidos a cirugía CMI por FVO.

Material y métodosEstudio retrospectivo de una serie de pacientes intervenidos mediante CMI por FVO. Se realizó un análisis descriptivo de las variables recogidas y se calcularon el volumen sanguíneo total (VST), el sangrado total (ST), el SO y la caída de hemoglobina (Hb). A continuación, se llevó a cabo una revisión comparativa entre el SO (<500 vs. ≥500mL) y las variables de estancia hospitalaria y evolución posoperatoria. Se hicieron modelos de regresión logística binaria para descartar factores de confusión.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 40 pacientes, ocho hombres y 32 mujeres, con una edad media de 76,6 años. El SO medio fue de 682,5mL. Se observó que un SO superior a 500mL es un factor de riesgo independiente de padecer una evolución posoperatoria tórpida (p=0,035), mientras que no predice una mayor estancia hospitalaria (p=0,116). Se calculó un aumento de SO en cirugías con más complejidad técnica, como de tiempo quirúrgico.

ConclusionesAunque las técnicas CMI han demostrado menor sangrado intraoperatorio, el SO debe ser identificado porque se asocia a una evolución tórpida. El uso de un algoritmo diagnóstico y terapéutico puede ayudar a minimizar su impacto.

Osteoporotic vertebral fractures (OVF) are generally diagnosed in patients older than 60 years of age with a variety of comorbidities and low bleeding tolerance that could decompensate them, something to be considered if the fracture requires surgery due to the risk of collapse.1

Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) techniques in the spine have been shown to prevent the collapse of OVF, with a low complication rate.2 One of the advantages of these techniques is lower intraoperative bleeding compared to open surgery, considering that MIS does not require an ample dissection of the paravertebral musculature.3,4

In recent studies, the term “hidden blood loss” (HBL) has been coined to refer to the loss of blood diffused into tissues and lost through hemolysis.4 Postoperative recovery can be seriously affected by this bleeding, increasing the rate of transfusions and medical complications and thus increasing hospital stay.5 However, most studies on MIS quantify intraoperative bleeding but do not consider the possibility of HBL.

We have clinically detected that some of our patients have a torpid evolution after MIS for OVF. Therefore, we performed a study to estimate the impact of HBL in the postoperative period. We also aimed to formulate a postoperative management proposal for early diagnosis to help minimize its consequences.

Materials and methodsThis was a retrospective study of clinical data from patients who underwent surgery for OVF using MIS techniques between June 1, 2020, and November 30, 2021. Only cases in which a control blood analysis was performed 24–48h after surgery were included. All surgeries were performed by the same specialized surgeon in our unit. The most appropriate surgical technique was decided according to the computer tomography fracture morphology based on the AO Spine-DGOU Osteoporotic Fracture Classification System6: vertebroplasty, percutaneous fixation one level above and below the fractured vertebra (1L-1L) cemented or uncemented, percutaneous fixation two levels above and below the fractured vertebra (2L-2L) cemented or uncemented, and combinations of these techniques.

We excluded all patients with pathological fractures, using anticoagulant or antiplatelet therapy (only 100mg acetylsalicylic acid was accepted, a drug that was withdrawn before surgery), with severe anemia (considered hemoglobin [Hb] <9g/dL), who had received a transfusion before surgery, or with hematological disorders such as thrombopenia and coagulation abnormalities.

Data were collected regarding sex, age, body mass index (BMI), cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF, considered dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, or diabetes mellitus), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) anesthetic risk classification,7 type of surgery, days of hospital stay (considering the day of discharge when the patient resumed independent ambulation), and postoperative evolution (a torpid evolution was defined as disproportionate pain, worsening of general condition, persistent nausea, desaturation, sustained arterial hypotension, orthostatic dizziness, or loss of appetite, which could ultimately lead to a relative delay in ambulation, considering the level of complexity of the fracture and the aggressiveness of the surgical procedure performed). Total blood volume (TBV), total bleeding (TB), HBL, and Hb drop were calculated according to the following equations.

The formulas used in earlier studies were applied for the calculation of HBL8:

Since the surgical aspirator used measures a minimum of 100mL, accurately recording intraoperative measured bleeding was not possible. However, this threshold was not exceeded in a high proportion of patients. For this reason, to carry out the necessary calculations and homogenize the results, we assumed that the intraoperative measured bleeding reached 100mL for all patients, considering that bleeding is also collected in surgical compresses.

TB was estimated using Gross et al.’s method,9 based on hematocrit levels before and after surgery (24–48h):

The method described by Nadler et al.,10 was used to calculate the patient's TBV.

where k1=0.3669, k2=0.03219, and k3=0.6041 for men, and k1=0.3561, k2=0.03308, and k3=0.1833 for women.The preoperative and postoperative Hb (after 24 or 48h, taking as reference the lowest value) were used to calculate the Hb drop, according to the equation used by Chen et al.4:

A descriptive analysis of the results was performed using IBM SPSS version 25 statistics software, expressing the results as mean±standard deviation for quantitative variables, and absolute values and percentages for qualitative variables. First, Pearson's Chi-square test and Student's t-test were employed, based on the characteristics of the outcome variable, to compare differences in hospital stay (in absolute terms and segmented into two subgroups, <4 days and ≥4 days, based on an automatically optimized cut-off point calculated using IBM SPSS) and postoperative evolution (torpid vs. favorable) depending on the calculated HBL (<500mL vs. ≥500mL). Two binary logistic regression models were carried out to estimate the association between postoperative evolution (torpid vs. favorable) and hospital stay (<4 days vs. ≥4 days), and the independent variable of HBL (<500mL vs. ≥500mL), taking into account potential confounding demographical variables (age, sex, CVRF, and BMI). A statistical significance value of 0.05 was assumed.

ResultsOnly 40 patients met the inclusion criteria because routine postoperative laboratory tests were not regularly carried out before our knowledge of HBL. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the sample. Table 2 shows the MIS technique used to treat OVF and its relative frequency.

Demographic data of the patient series.

| Menn=8 (20.0%) | Womenn=32 (80.0%) | Totaln=40 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 79.8±8.8 | 75.9±7.1 | 76.7±7.5 |

| CVRF | 7 (87.5%) | 29 (90.6%) | 36 (90.0%) |

| BMI | 28.7±4.9 | 26.6±3.9 | 27.0±4.1 |

| Normal weight (BMI 18.5–24.9kg/m2) | 3 (37.5%) | 11 (34.4%) | 14 (35.0%) |

| Overweight (BMI 25–29.9kg/m2) | 2 (25.0%) | 17 (53.1%) | 19 (47.5%) |

| Obese (BMI >30kg/m2) | 3 (37.5%) | 4 (12.5%) | 7 (17.5%) |

| ASA | |||

| II | 7 (87.5%) | 28 (87.5%) | 35 (87.5%) |

| III | 1 (12.5%) | 4 (12.5%) | 5 (12.5%) |

BMI: body mass index; CVRF: cardiovascular risk factors; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists anesthetic risk classification; n: number of patients.

Frequency of the different MIS techniques used.

| MIS technique | Totaln=40 |

|---|---|

| Vertebroplasty | 2 (5.0%) |

| 1L-1L cementless fixation | 10 (25.0%) |

| 2L-2L cementless fixation | 9 (22.5%) |

| 2L-2L cemented fixation | 7 (17.5%) |

| 1L-1L cementless fixation+vertebroplasty | 3 (7.5%) |

| 1L-1L cemented fixation+vertebroplasty | 1 (2.5%) |

| 2L-2L cementless fixation+vertebroplasty | 7 (17.5%) |

| 2L-2L cemented fixation+vertebroplasty | 1 (2.5%) |

MIS: minimally invasive surgery; 1L-1L: one level above and below the fractured vertebra; 2L-2L: two levels above and below the fractured vertebra; n: number of patients.

Table 3 summarizes the data regarding Hb drop, TBV, TB, and HBL according to the MIS technique employed. The HBL calculated for cementless 1L-1L fixation technique combined with vertebroplasty had a negative result of −46.4mL because a TB of less than 100mL was calculated.

Hb drop, TBV, TB, and HBL.

| MIS technique | Hb drop(g/dL) | TBV(L) | TB(mL) | HBL(mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vertebroplasty | 1.3±1.2 | 3.5±0.3 | 488.5±565.3 | 388.5±565.3 |

| 1L-1L cementless fixation | 1.9±1.6 | 4.2±0.5 | 669.1±582.0 | 569.1±582.0 |

| 2L-2L cementless fixation | 2.4±1.3 | 4.3±0.7 | 765.7±362.0 | 665.7±362.0 |

| 2L-2L cemented fixation | 2.7±1.2 | 4.0±0.2 | 912.1±336.9 | 812.1±336.9 |

| 1L-1L cementless fixation+vertebroplasty | 0.3±0.6 | 4.0±0.3 | 53.6±220.0 | −46.4±220.0 |

| 1L-1L cemented fixation+vertebroplasty | 2.9±0.0 | 3.2±0.0 | 938.6±0.0 | 838.6±0.0 |

| 2L-2L cementless fixation+vertebroplasty | 2.9±1.6 | 4.2±0.5 | 1108.7±705.7 | 1008.7±705.7 |

| 2L-2L cemented fixation+vertebroplasty | 4.3±0.0 | 3.6±0.0 | 1493.3±0.0 | 1393.26±0.0 |

| Total mean | 2.3±1.5 | 4.1±0.5 | 782.5±542.4 | 682.5±542.4 |

MIS: minimally invasive surgery; 1L-1L: one level above and below the fractured vertebra; 2L-2L: two levels above and below the fractured vertebra; Hb: hemoglobin; TBV: total blood volume; TB: total bleeding; HBL: hidden blood loss.

Data related to hospital stay and torpid postoperative evolution, segmented by HBL <500mL and ≥500mL, are shown in Table 4. Binary logistic regressions models performed show that HBL ≥500mL is the only independent risk factor in predicting a torpid evolution when other confounding demographical variables are taken into account (odds ratio [OR]=7.030, p-value=0.035). In contrast, it does not predict a longer hospital stay of ≥4 days (OR=3.188, p-value=0.116).

Hospital stay and evolution by calculated HBL.

| HBL <500mLn=15 (37.5%) | HBL ≥500mLn=25 (62.5%) | Totaln=40 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital stay (days) | 3.5±1.8 [range 1–9] | 5.1±3.4 [range 1–15] | 4.5±3.0 [range 1–5] | 0.067 |

| <4 days | 9 (60%) | 9 (36%) | 18 (45%) | 0.140 |

| ≥4 days | 6 (40%) | 16 (64%) | 22 (55%) | |

| Torpid postoperative evolution | 2 (13.3%) | 11 (44.0%) | 13 (32.5%) | 0.045 |

HBL: hidden blood loss; n: number of patients.

Statistical significance is determined by p < 0.05 (bold).

The incidence of OVF has increased with the aging population.11 Patients with OVF may experience pain, spine deformity, functional disability, depression, decreased quality of life and associated increased risk of adjacent fractures and mortality.2

The development of minimally invasive techniques for approaching these fractures has made it possible to indicate surgery in patients whose age and comorbidities contraindicate open surgery. Thus, the mean age of our series of patients was 76.7 years. These patients had a high percentage of CVRF and were markedly overweight. Their age was similar to the patients of Cao et al. (75 years)5 and Wu et al. (71 years)12 and younger than those of Cai et al. (88.14 years).1

The mean HBL calculated in our series was 682.5mL. Analyzing the results according to the technique used, a higher calculated HBL was observed in longer procedures. Thus, cemented 2L-2L fixation combined with vertebroplasty showed the highest calculated HBL. In contrast, vertebroplasty, which is usually a relatively fast procedure, had a calculated HBL of 388.5mL. Similarly, Wu et al.,12 estimated an HBL of 256mL in patients with one-level fractures treated by kyphoplasty.

For fractures treated by percutaneous 1L-1L fixation, an HBL of 569.1mL was calculated, higher than that found by Chen et al. (240mL).4 This difference may be explained because the patients in that series were young, with traumatic fractures, a mean age of 45.3 years, and a BMI of 23.1.

Statistically significant differences existed in postoperative outcomes according to HBL. Binary logistic regression models showed that a higher calculated HBL is associated with a torpid postoperative evolution in a more significant number of patients (p=0.035) when controlling for other potential confounding demographical factors. On the other hand, although the absolute mean hospital stay is somewhat longer in the group of patients with a calculated HBL of ≥500mL, this was not found to be a statistically significant risk factor when considering other control factors in a binary logistic regression model.

As this study shows, post-surgical bleeding and its possible consequences in elderly patients are unavoidable. In the event of a torpid postoperative evolution, analyzing the drop in Hb is crucial, not only the absolute value in postoperative control blood tests. The absolute Hb value may be in range postoperatively and not recommend blood transfusion (according to international guidelines, it would only be indicated when Hb is below 7g/dL13), but a drop of more than three points could have an impact on the patient's clinical course. For example, suppose a patient is admitted for OVF with a preoperative Hb of 12g/dL, and the Hb drops to 8g/dL after surgery. In that case, although this Hb would not indicate a red blood cell transfusion, such a significant drop is likely to have clinical consequences on the patient's outcome. Similar to hip surgery,14 we consider it advisable to adapt the transfusion threshold to each case.

Some authors suggest using preoperative intravenous tranexamic acid to minimize the rate of surgical bleeding, and thus its consequences, in patients with percutaneously treated thoracolumbar fractures.15 However, its use is still under discussion, and its indication is off-label.

After analyzing our results, we have developed a protocol for early detection and treatment of HBL after MIS for OVF (Fig. 1). We believe it could be used in clinical practice to minimize the effects of HBL and help discard other causes of bleeding.

Our study has some limitations. First, this was a retrospective observational study with a limited series of cases. For this reason, we were unable to carry out a detailed stratified analysis grouping patients according to the type of fracture and the treatment performed. However, it was the first Spanish series of patients undergoing surgery for OVF using MIS techniques to study HBL and the first to propose a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. The calculation of HBL assumed that the measured bleeding was 100mL, which could have altered the results, given that this value was not reached in most cases. However, other authors, such as Cao et al.,5 ignored intraoperative measured bleeding in their calculations. Furthermore, importantly, only those patients who had a blood test 24–48h after surgery (according to the defined criteria) were included, and therefore the results obtained may have overstated the overall importance of HBL in this type of surgery. Moreover, we have not taken into account other postoperative blood parameters like serum electrolytes that could have potentially influenced the results. Finally, our population's advanced mean age may have resulted in a higher calculated HBL due to an increased tendency to global bleeding.

Conclusions- -

Although MIS techniques for OVF have shown less intraoperative bleeding than open surgery, intraoperative HBL has not always been recognized. However, HBL should be pro-actively considered since it is associated with a poor postoperative outcome.

- -

The detection of a significant drop in hemoglobin (despite postoperative hemoglobin within normal range that does not indicate a blood transfusion) may reflect a higher HBL and, consequently, predict an unfavorable postoperative outcome.

- -

The use of an algorithm for early diagnosis and management of HBL may help minimize its impact in elderly patients.

Level of evidence IV.

Ethical approvalEthical approval was obtained from the local Ethics Committee for Drug Research (CEIm) of Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia (order no. 2022/012). Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

FundingNone declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there are no relevant conflicts of interest.