Cervical facet injuries pose a complex clinical challenge. Management strategies and prognosis remain under debate in the literature. This study aims to describe a series of cases to identify factors that facilitate decision-making in the management and prognosis of these fractures.

MethodsA retrospective study of patients with unilateral cervical facet fractures (F2 or F3, AO Spine classification) was conducted at a single trauma center. The study included 46 males and 4 females aged 21–65 years. All patients underwent initial spine CT scans, radiographs and MRI. Management was based on fracture stability and clinical presentation. Patients were categorized into F2/F3 groups and further subdivided based on initial management: orthopedic, emergency surgery (kyphosis >11°, listhesis >3.5mm, or neurological compromise), and planned surgery. Follow-up included imaging studies and specialist consultation. In cases where conservative management failed, surgery was performed.

ResultsFifty patients were diagnosed with cervical facet fractures, with the C6–C7 segment being the most commonly affected (53.06%). Nine patients required emergency surgery, all had disc injury, and 7 (77.7%) presented with listhesis >2mm. Among patients receiving orthopedic management, 7 (25%) experienced treatment failure, all of whom exhibited disc injury, facet synovitis, and prevertebral edema. The success rate for conservative treatment differed between groups: 84.2% in the F2 group and 55.5% in the F3 group. No patient exhibited persistent neurological deficits at follow-up.

ConclusionThe presence of disc lesions and facet synovitis significantly influences treatment outcomes, underlining the need for tailored approaches to optimize patient care.

Las lesiones facetarias cervicales representan un desafío clínico complejo. Las estrategias de manejo y el pronóstico continúan siendo motivo de debate en la literatura. Este estudio tiene como objetivo describir una serie de casos para identificar factores que faciliten la toma de decisiones en el manejo y pronóstico de estas fracturas.

MétodosSe realizó un estudio retrospectivo de pacientes con fracturas unilaterales de facetas cervicales (clasificación F2 o F3 según AOSpine) en un único centro de traumatología. Se incluyeron 46 hombres y 4 mujeres, con edades entre los 21 y los 65 años. Todos los pacientes fueron evaluados inicialmente con tomografía computarizada de columna, radiografías y resonancia magnética. El manejo se definió según la estabilidad de la fractura y la presentación clínica. Los pacientes se categorizaron en grupos F2 y F3, y posteriormente se subdividieron según el tratamiento inicial: ortopédico, cirugía de urgencia (cifosis>11°, listesis>3,5mm o compromiso neurológico) y cirugía programada. El seguimiento incluyó estudios de imagen y evaluación por especialistas. En los casos en que el tratamiento conservador fracasó, se realizó intervención quirúrgica.

ResultadosSe diagnosticaron fracturas facetarias cervicales en 50 pacientes, siendo el segmento C6-C7 el más frecuentemente afectado (53,06%). Nueve pacientes requirieron cirugía de urgencia; todos presentaban lesión discal y 7 de ellos (77,7%) mostraban listesis >2mm. Entre los pacientes que recibieron manejo ortopédico, 7 (25%) presentaron fracaso del tratamiento; todos ellos mostraban lesión discal, sinovitis facetaria y edema prevertebral. La tasa de éxito del tratamiento conservador fue distinta entre grupos: 84,2% en el grupo F2 y 55,5% en el grupo F3. Ningún paciente presentó déficits neurológicos persistentes en el seguimiento.

ConclusiónLa presencia de lesiones discales y sinovitis facetaria influye significativamente en los resultados del tratamiento, lo que subraya la necesidad de enfoques individualizados para optimizar el cuidado del paciente.

Cervical spine fractures are serious, relatively rare injuries, accounting for 2–3% of patients who suffer trauma.1,2 The annual incidence of subaxial fractures is 10/100,000,2,3 and less than 5% of all cervical spine injuries are isolated or non-displaced facet fractures.3,4 Despite their low incidence, due to the increased availability of computed tomography (CT) and its routine use in polytrauma patients, these injuries are being detected more frequently,5 facilitating early diagnosis and management.

Facet injuries are usually the result of a flexion moment that causes distraction and failure of the posterior elements.2 These fractures range from simple non-displaced injuries to displaced comminuted fractures; however, depending on clinical and radiological variables, the same bone injury pattern may behave as either a stable or unstable lesion.4 The involvement of osteoligamentous structures is crucial in determining the definitive treatment,6 and an acute intervertebral disc injury along with posterior ligament involvement can result in a non-displaced fracture or a dislocated facet with adequate reduction behaving as an unstable fracture requiring surgical treatment.3,6,7

Actually, there is an ongoing debate on the management of isolated facet fractures, especially among neurologically intact patients. Although some agreement exists, the literature reports failure rates of conservative treatment ranging from 20% to 80%,8,9 underscoring the absence of a universally accepted management algorithm.

Cervical facet fractures continue to generate controversy in many aspects, including the optimal management based on the morphology and severity of the injury. The objective of this study is to describe a series of patients who presented with facet fractures classified as F2 and F3 according to the AO classification.

Materials and methodsFor this case series, a comprehensive review of the database of a single Level I trauma center in Santiago, Chile, was conducted. Between 2009 and 2023, 69 patients were initially selected, of which 16 had type F1 fractures and three had a bilateral injury, resulting in a final sample of 50 patients. The inclusion criteria were: patients over 18 years of age, with unilateral cervical facet fractures classified as F2 or F3 according to the AO Spine Classification, and completeness of their electronic medical records. Facet measurement was performed using the method described by Spector.11 The minimum follow-up period was defined as the time required to achieve fracture consolidation, confirmed by CT imaging. The exclusion criteria were: patients with bilateral facet dislocation, associated cervical spine fractures requiring surgical stabilization (e.g., vertebral body fractures or burst fractures), spinal cord injury at presentation, prior cervical spine surgery, or incomplete radiological records.

Surgical treatment was indicated in listhesis >3.5mm, neurological compromise, and/or kyphosis >11°. Conservative management was selected for neurologically intact patients without radiographic signs of instability.

All patients underwent evaluation with X-rays and CT scans (Diamond Select Brilliance CT 16 channels; Philips, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). All patients were evaluated with magnetic resonance (MRI; Phillips Ingenia 1.5 or 3.0 Tesla) imaging following our center's cervical fracture study protocol, and patients were subsequently assessed by expert spine surgeons. The surgical group underwent arthrodesis with instrumentation of one or two levels, through anterior, posterior, or combined approaches as appropriate. In the orthopedic management group, strict cervical collar use was indicated day and night for 6–8 weeks, with serial radiological follow-ups by the spine team. Treatment failure was defined as the progression of listhesis, the appearance of neurological compromise, or non-union. In case of treatment failure, patients underwent surgery.

Demographic, clinical, and radiological variables were analyzed. Finally, a variable correlation was performed using Stata software, applying the chi-square test for qualitative variables and the Student's t-test for quantitative variables. This study was approved by the local hospital ethics committee.

ResultsFifty patients were selected: 46 men and four women, between 21 and 65 years of age (mean age 40.1, SD 12.7). High-energy trauma accounted for 90% of cases, including falls from a height greater than two meters, traffic accidents, motorcycle crashes, or pedestrian accidents. Fifty-four percent of the patients presented the lesion on the left side. The F2 group included 27 participants, while the F3 group comprised 23 participants. The mean follow-up of surgically treated patients was 15.9 months (SD 27.6), with a median of 7.3 months (IQR 3.6–15.0). Patients were followed until discharge, which in most cases occurred around 3 months after injury. Overall, 94% of patients achieved return to work. The three patients who did not resume their occupational activities had persistent sequelae secondary to severe traumatic brain injury.

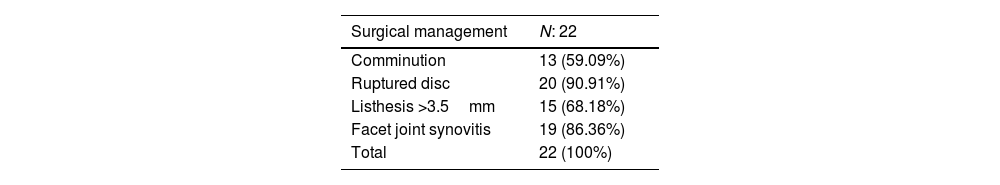

Surgical groupInitially, surgical management was indicated in 22 patients (44%). Nine patients underwent emergency surgery due to neurological compromise and/or associated instability. The remaining patients were operated on within the first two weeks, depending on hemodynamic stability resulting from other injuries. The anterior approach was the most commonly used (82.8%, N=18). Three (13.6%) patients underwent a dual approach. Only one required a posterior approach, the patient, a professional singer, declined the anterior approach due to the associated risk of recurrent laryngeal nerve injury. In 50% of cases, one level was instrumented, while in the other 50%, two levels were instrumented.

Regarding imaging variables, 59% of patients had facet comminution, 90% presented with disc rupture, 68% had listhesis, and 86% exhibited facet synovitis (Table 1).

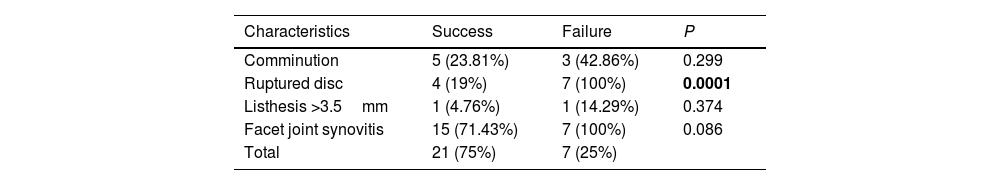

Orthopedic groupA total of 28 patients were managed with orthopedic treatment. Of these, seven experienced treatment failure (six due to listhesis progression and one due to non-union). Table 2 compares the radiological characteristics of both groups. Notably, disc rupture was present in 100% of the patients who failed orthopedic management and was the only variable with statistical significance (P<0.05). Although facet synovitis was also present in the failure group, it did not reach statistical significance.

Imaging characteristics of patients with successful conservative management versus failure.

| Characteristics | Success | Failure | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comminution | 5 (23.81%) | 3 (42.86%) | 0.299 |

| Ruptured disc | 4 (19%) | 7 (100%) | 0.0001 |

| Listhesis >3.5mm | 1 (4.76%) | 1 (14.29%) | 0.374 |

| Facet joint synovitis | 15 (71.43%) | 7 (100%) | 0.086 |

| Total | 21 (75%) | 7 (25%) |

In bold, statistically significant P value.

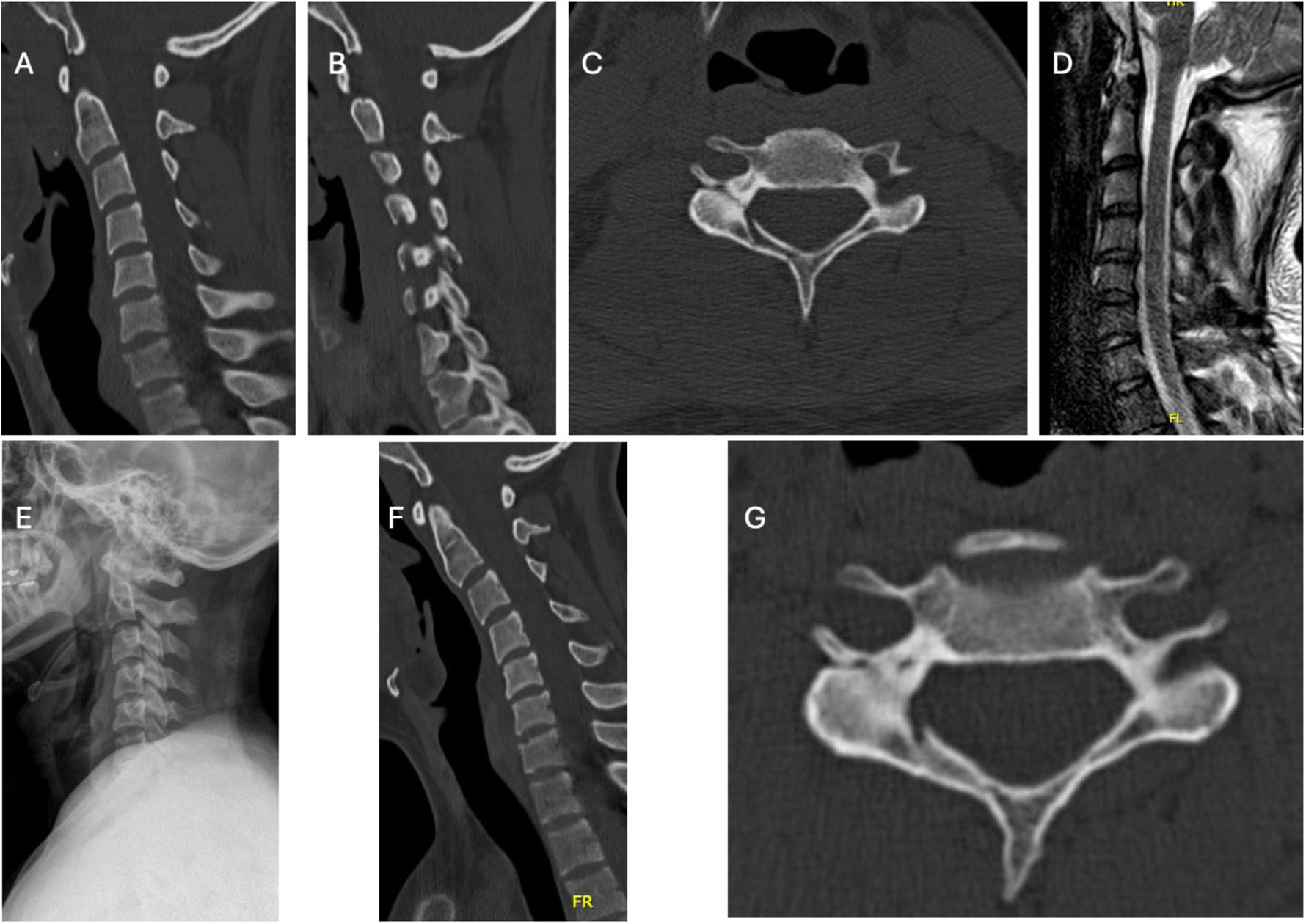

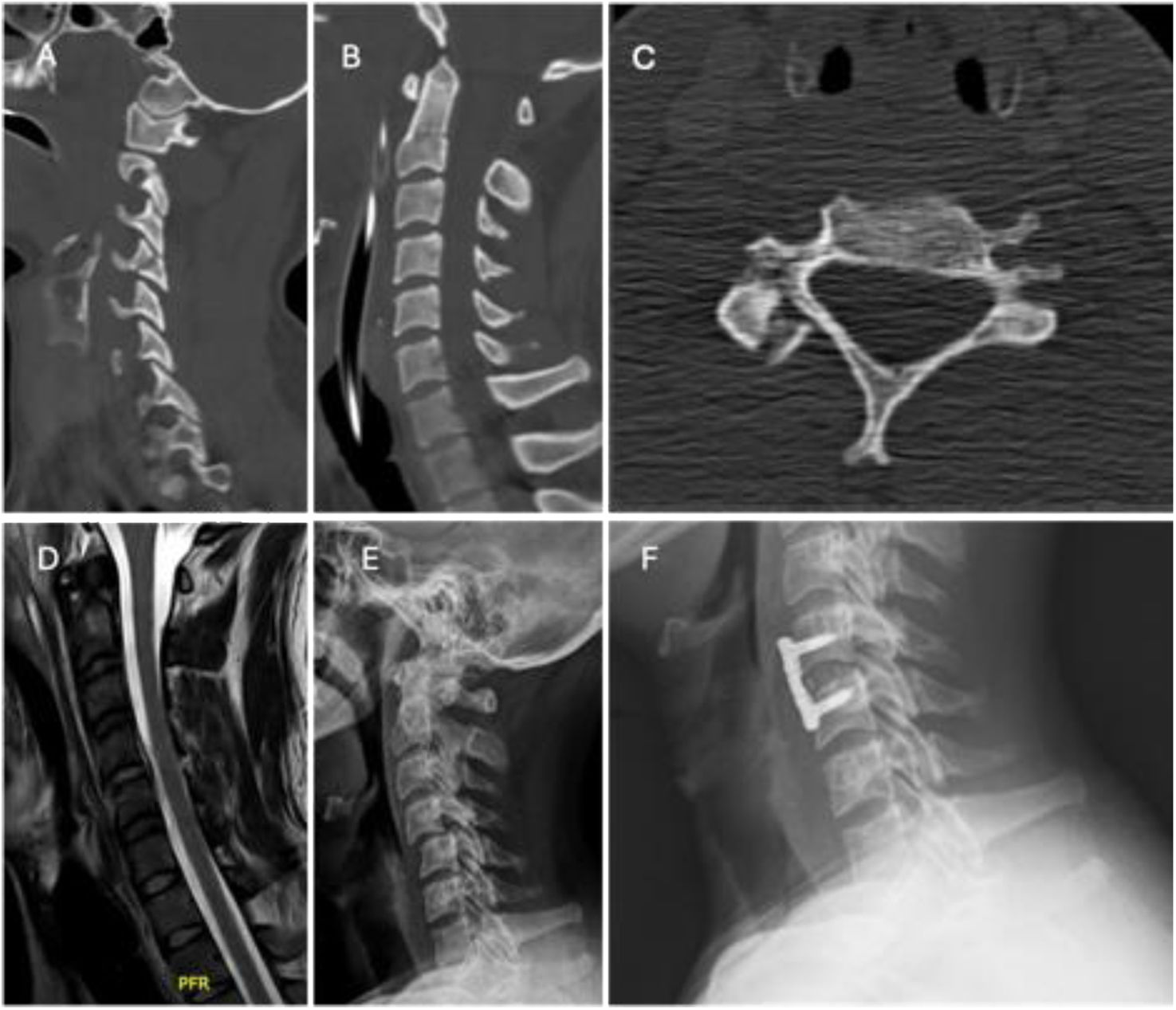

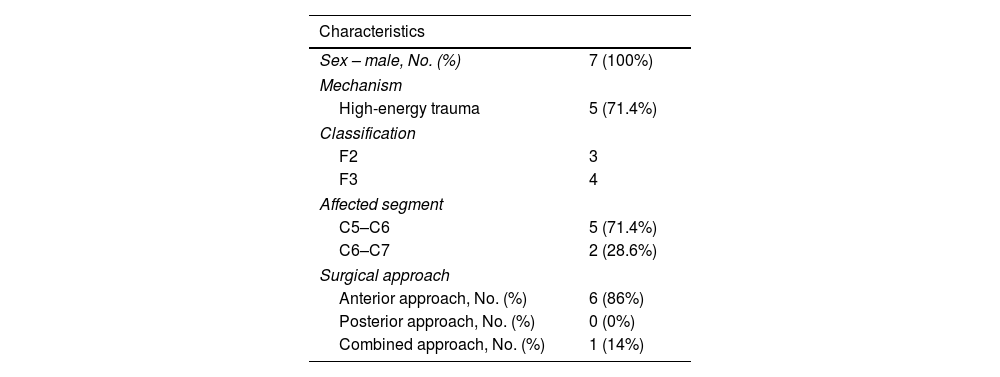

Regarding the treatment failure group, all patients were male, and five sustained high-energy trauma. Four cases corresponded to F3 fractures, while three were classified as F2. The most affected segment was C5–C6, and the anterior approach was used in six patients. Only one case required a combined approach. In six cases, a single segment was instrumented (Table 3). Figs. 1 and 2 show an example of successful orthopedic management and one that failed, respectively.

Conservative management failure.

| Characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Sex – male, No. (%) | 7 (100%) |

| Mechanism | |

| High-energy trauma | 5 (71.4%) |

| Classification | |

| F2 | 3 |

| F3 | 4 |

| Affected segment | |

| C5–C6 | 5 (71.4%) |

| C6–C7 | 2 (28.6%) |

| Surgical approach | |

| Anterior approach, No. (%) | 6 (86%) |

| Posterior approach, No. (%) | 0 (0%) |

| Combined approach, No. (%) | 1 (14%) |

Case example (M.B.): 22 years old man with a F3 C5 right facet fracture. (A) Cervical CT sagittal view without evidence of cervical listhesis. (B) Cervical CT sagittal view showing F3 fracture at C5. (C) Cervical CT axial view showing floating lateral mass. (D) Evidence of C4–C5 healthy disc on MRI (T2) sagittal view. (E) X-ray control at 6 weeks showing no evidence of listhesis. (F and G) Cervical CT follow-up at 3 months showing advanced consolidation.

Case example (P.V.): 27 years old man with a F3 C4 right facet fracture. (A) Cervical CT sagittal view showing F3 fracture at C5. (B) Cervical CT sagittal view without evidence of cervical listhesis. (C) Cervical CT axial view showing lateral mass fracture with comminution. (D) Evidence of C4–C5 acute disc injury on MRI (STIR) sagittal view. (E) X-ray control at 6 weeks with evidence of C4–C5 progressive listhesis. (F) C4–C5 anterior cervical discectomy and fusion.

In our case series, the failure rate was 25% (7 out of 28 patients), of whom 4 had F3 fractures. All patients who failed conservative management presented with a disc injury. Furthermore, although facet synovitis was identified in a high proportion of patients, it did not reach statistical significance in relation to conservative treatment failure. In our series, the most commonly used approach was anterior (82.7%) with ACDF, and the only case managed with a posterior approach was at the patient's request. The success rate in terms of consolidation was 100%, with no neurological sequelae, and 94% of patients achieved return to work, emphasizing the importance of early intervention in patients with clear instability criteria.

Facet fractures are low-incidence injuries that require a high index of suspicion for diagnosis. The increased use and availability of CT scans have helped reduce delayed diagnosis,5 but the literature reports that management remains controversial.4,10,11 Spector et al., in 2006, demonstrated that the most important risk factor for conservative management failure was facet involvement >40% and/or greater than 1cm.11 Although their sample included only 24 patients, their findings were considered in the AO facet fracture classification developed in 2014.12 Based on such a small sample, one might assume that the AO classification may not achieve a management consensus. However, Karamian et al., in 2020, attempted to determine the variation in global treatment practices for unilateral subaxial cervical spine facet fractures based on surgeon experience and practice setting. They concluded that there is currently considerable agreement in management, except in cases with radiculopathy.9 Additionally, following this trajectory, Canseco et al., in 2020, aimed to assess whether geographic location and surgeon experience influenced the management of these injuries. With a total of 189 surveys, they concluded that there was a general consensus on treatment, with the anterior approach being the preferred method.13 Both studies utilized the AO classification.

The facet joints and their ligamentous capsules are the primary dynamic stabilizers of the cervical spine, allowing multidimensional movements without compromising neural elements.2 Therefore, the involvement of soft tissues, such as the posterior ligamentous complex, joint capsules, and intervertebral discs, are key factors in defining management. The historically described criteria for instability in cervical traumatic injuries include: disruption of the anterior and/or posterior tension bands, segmental kyphosis greater than 11°, vertebral displacement greater than 3.5mm, and axial rotation exceeding 11°.14,15 The decision to proceed with surgical intervention is often driven by the presence of disco-ligamentous disruption observed in the STIR sequence of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), as such injuries present a higher risk of subluxation, late kyphosis, worsening pain, and neurological injuries when managed with external rigid immobilization. The use of MRI is essential, and most spine surgeons request it to define the final treatment plan.13

Regarding the risks of conservative management failure, factors such as facet or articular mass comminution, fragment diastasis, acute disc injury, bilateral fractures, fractures affecting 40% of the intact height of the lateral mass or with an absolute height of 1cm, greater initial displacement, listhesis >2cm, higher body mass index (BMI), radiculopathy at presentation, and a higher injury severity score (ISS) are considered risk factors for conservative treatment failure.14,15,19 Furthermore, according to the study by Cirillo et al. in 2023, with a sample of 37 patients, acute disc injury has a strong association with conservative treatment failure in patients with F2 and F3 fractures.4 The finding that 100% of patients in whom conservative treatment failed had disc rupture is consistent with previous studies identifying this variable as a strong predictor of failure in non-surgical treatment.4,19 This result suggests that disc rupture should be considered a key marker in the initial management decision, as its presence may be associated with a higher likelihood of treatment failure. The literature suggests that synovitis may be a sign of instability and, when combined with other findings such as disc rupture, could serve as an additional clinical indicator when deciding on the most appropriate treatment approach.4,19

On the other hand, orthopedic management is a valid alternative in cases without displacement or neurological compromise.15 However, Dvorak et al., in 2007, reported a study of 90 patients with facet fractures – the largest series published to date – showing that patients treated conservatively had worse short- and long-term functional outcomes.10 In our series, the failure rate was 25%; however, the return-to-work rate reached 94%, representing a very favorable functional outcome.

Regarding surgical management, the anterior, posterior, or combined approaches are viable options. In the study by Chaput et al., a cadaveric study with a case series of 11 patients with unilateral F3 fractures, the stability achieved with posterior screw fixation was compared to the stability obtained with the anterior approach using a cage with screws and an anterior plate. The results showed that posterior fixation achieved significant reduction in all three planes, while the use of a cage with an anterior plate significantly reduced flexion/extension and lateralization movements. In their case series, all patients underwent the anterior approach, with no reported complications.16 In the prospective study by Manoso et al., which included 60 patients with unilateral F3 fractures, all cases managed conservatively exhibited a translation greater than 3mm, and 75% required surgical intervention. Among those who underwent single-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF), 83% had a displacement greater than 3mm. Of the patients who received a two-level ACDF, comprising 60% of the total sample, none experienced translation or implant failure. The posterior approach was used in cases of multiple fractures or for decompression in the presence of neurological compromise.17 Additionally, Rabb et al., in 2007, in their retrospective study of 25 surgically managed patients, concluded that the optimal approach for these fractures was anterior, although a small percentage of cases could present an associated vertebral artery injury.18 In our series, the anterior approach (82.7%) with ACDF was most frequently employed, achieving consolidation in all cases and with no intraoperative or postoperative complications observed.

The management and treatment strategies for this type of injury are diverse. In an effort to provide a structured approach to these injuries, Cirillo et al. developed a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm.14 For F1 fractures, orthopedic management with a cervical collar for at least 6 weeks is recommended, with radiological follow-up at 2 and 4 weeks. For potentially unstable F2 fractures, once severe type B or C (AO) injuries and signs of instability are ruled out, orthopedic management with a collar for 6 weeks and radiological follow-up is advised. If treatment fails, anterior cervical arthrodesis should be performed. For F3 fractures, it is recommended to assess disc integrity. If the disc is injured, surgery for single- or bi-segmental arthrodesis is suggested. If the disc is intact and there are no other signs of instability, non-surgical treatment with a rigid collar for 12 weeks is advised. Finally, for F4 fractures, they should be managed as type C fractures according to the AO classification.14

This study has several strengths. All patients were evaluated with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging, which allowed for a detailed characterization of fractures and associated disco-ligamentous injuries. The cohort was homogeneous, derived from a single trauma center with standardized diagnostic and therapeutic criteria, thereby reducing variability in management. Moreover, all patients were followed until fracture consolidation and/or occupational discharge, ensuring that the main clinical outcomes were adequately recorded. However, the retrospective design and the small sample size are important limitations. Given the low prevalence of these types of injuries, prospective multicenter studies are needed to improve management strategies for these fractures.

ConclusionIn conclusion, our results emphasize the importance of a thorough evaluation of imaging and clinical characteristics in patients with cervical facet fractures. Disc rupture was found to be associated with failure of conservative treatment, indicating that surgical treatment should be considered early in patients with this finding. Despite the available guidelines and classifications, significant uncertainty remains regarding management criteria, particularly in F2 and F3 fractures. This underscores the need for further studies to refine treatment strategies and improve long-term functional outcomes.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical considerationsThis was an observational and retrospective study; no interventions were made in the management of the patients. Informed consent was not required. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the hospital center.

FundingThe authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

To the AO Spine Latin America Trauma Study Group.