It has been shown that total knee replacement improves functional capacity and physical activity; however, the influence of age remains unclear. The objective is evaluate the pre and postoperative physical activity measured with the Knee Society Score (KSS) score and the Tegner score.

Materials and methodsA retrospective cohort analysis was conducted on patients who underwent total knee replacement (TKR) between January 2016 and December 2019 at our institution. Demographic variables (age, sex, and body mass index), activities of daily living, age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index, American Society of Anesthesiologists score, the Knee Society Score (KSS) in its clinical (KSSc) and functional (KSSf) subscales, the Tegner functional scale, activity variables from the 2011 KSS version, and pain assessment using the visual analogue scale were collected. Differences in these variables were analysed between two age groups: group A (between 65 and 79 years old) and group B (80 years or older).

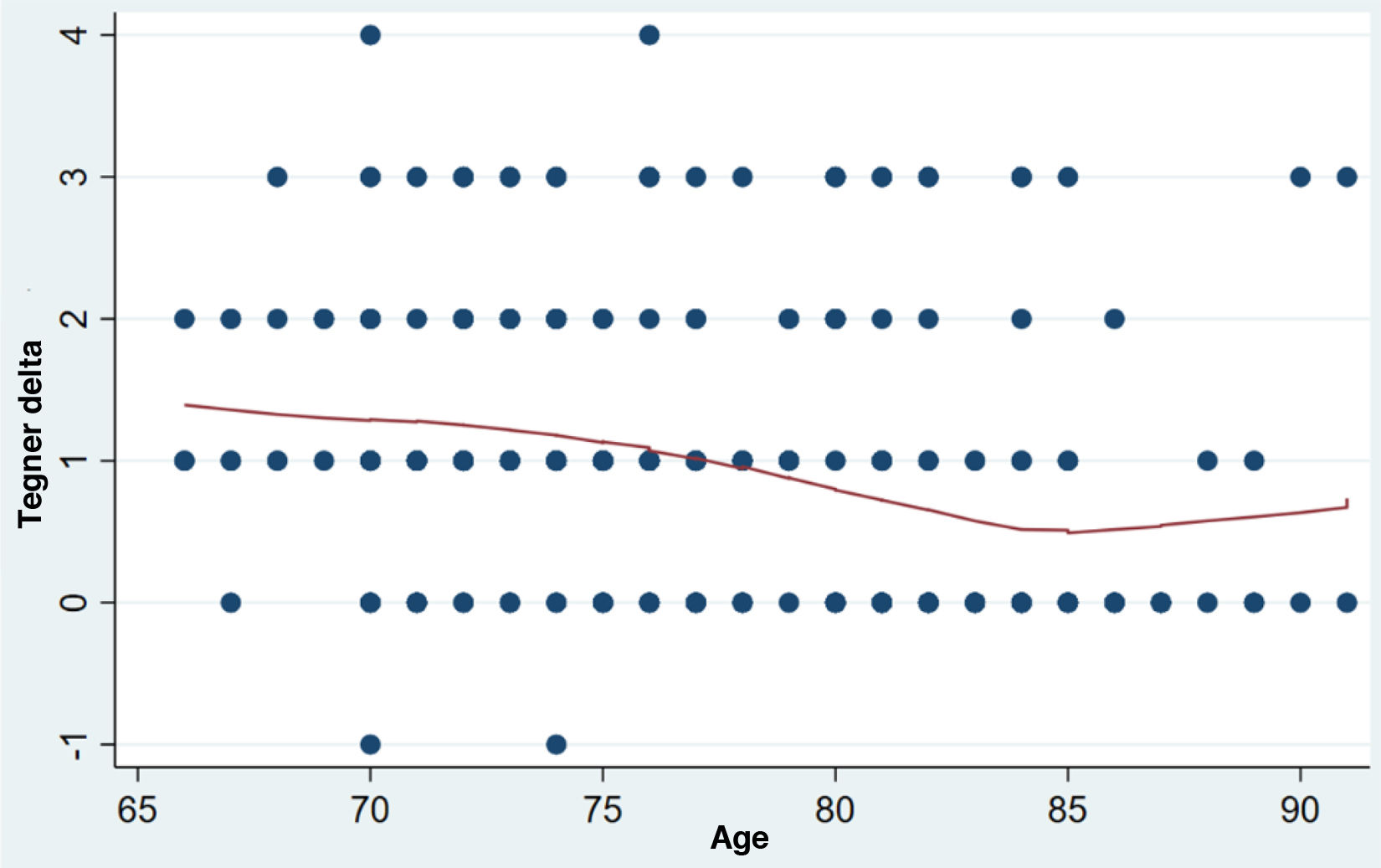

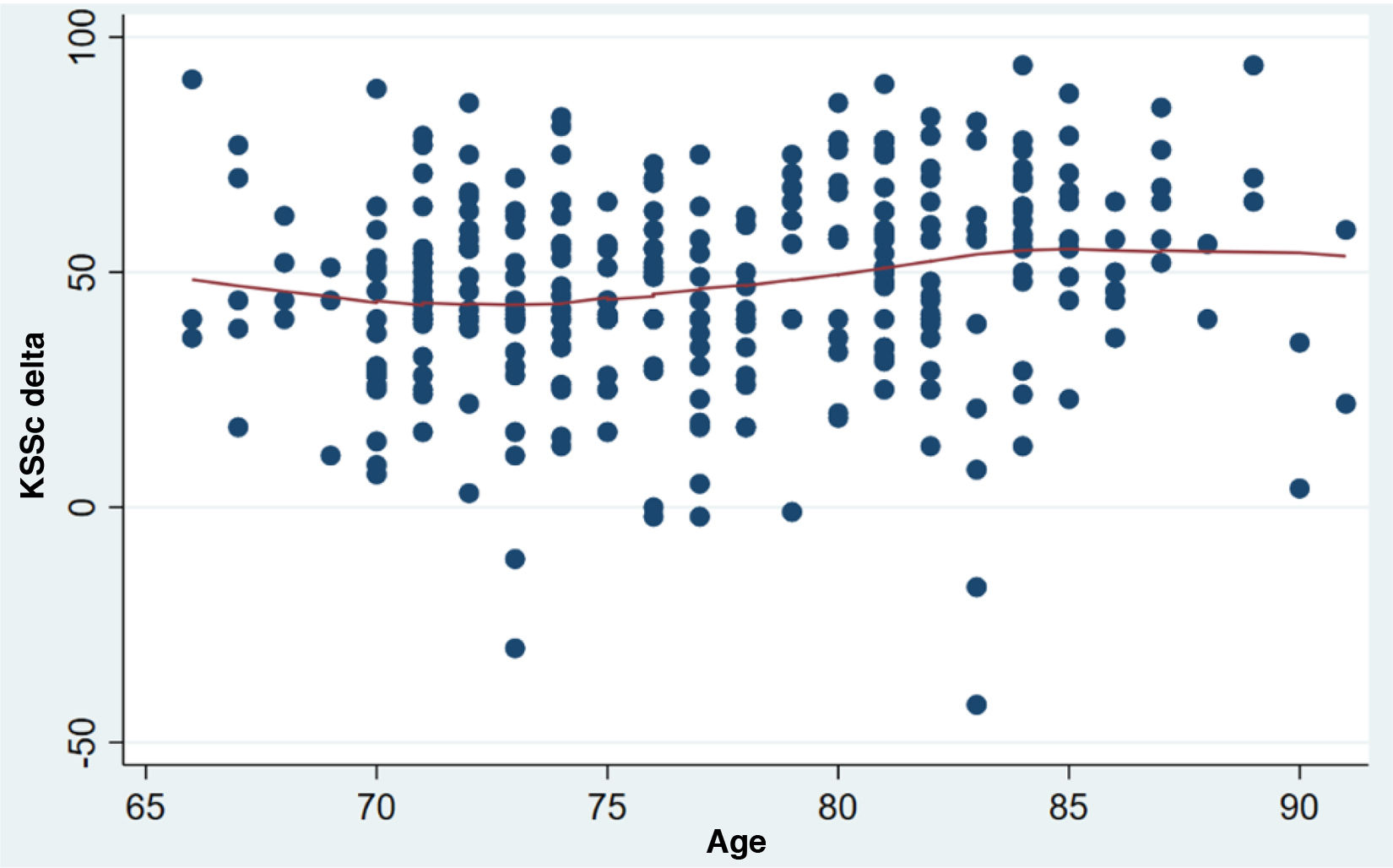

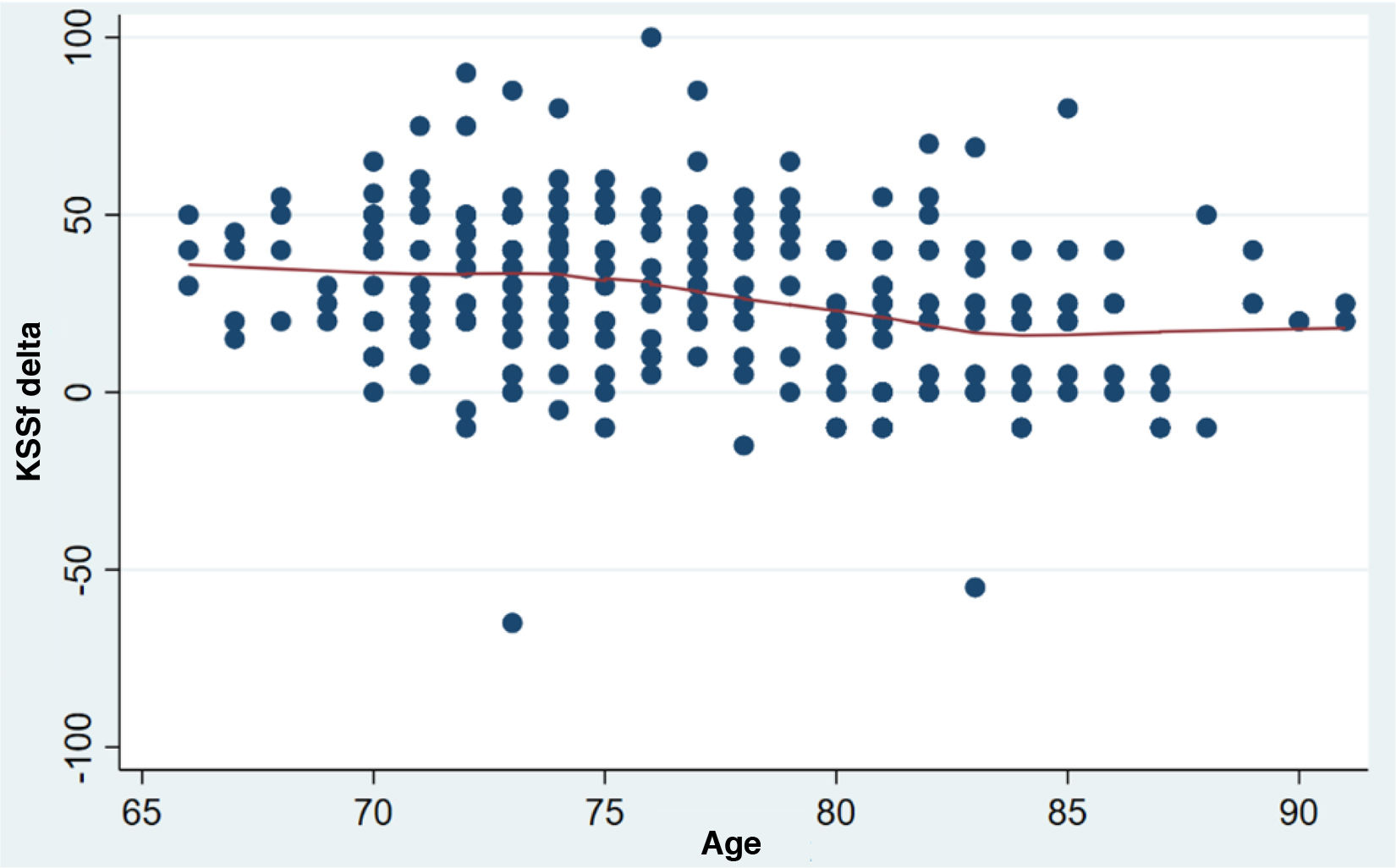

ResultsA total of 450 patients were evaluated (group A=245, group B=167). Group A showed a Tegner improvement of 1.19 (95% CI: 1.06–1.31), whereas group B averaged 0.61 (95% CI: 0.43–0.80) (p<.001). Age>80 was an independent risk factor for less Tegner improvement. In KSSc, group A improved by 43 points (95% CI: 40.82–46.14), while group B showed a greater increase of 53 points (95% CI: 49.74–57.80). Adjusted for confounders, those >80 showed significantly higher KSSc improvement (12.8 points). For KSSf, group A improved by 33.91 points (95% CI: 31.07–36.75), and group B by 15.57 points (95% CI: 11.78–19.35). Adjusted for confounders, patients >80 had less improvement than those <80 (19 points).

ConclusionsPatients who underwent TKR experienced improvements in physical and functional activity parameters. While these improvements were seen in the entire population, they were most notable in patients younger than 80 years.

Se ha demostrado que el reemplazo total de rodilla (RTR) mejora la capacidad funcional y de realizar actividad física; sin embargo, la influencia de la edad aún no está clara. El objetivo de este trabajo es evaluar la actividad física pre y postoperatoria medida con el puntaje de la Knee Society Score (KSS) y el puntaje de Tegner.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un análisis de cohorte retrospectivo de pacientes sometidos a RTR entre enero de 2016 y diciembre de 2019 en nuestra institución. Se recogieron las variables demográficas (edad, sexo e índice de masa corporal), las actividades de la vida diaria, el índice de comorbilidad de Charlson ajustado por edad, la puntuación de la Sociedad Americana de Anestesiología, la escala de la KSS, en sus subescalas clínica (KSSc) y funcional (KSSf), la escala funcional de Tegner, las variables de actividad del KSS versión 2011 y la evaluación del dolor mediante la escala visual analógica. Se analizaron las diferencias en estas variables entre 2 grupos según la edad: grupo A (entre 65 y 79 años) y grupo B (iguales o mayores a 80 años).

ResultadosSe evaluaron 450 pacientes (grupo A=245; grupo B=167). El grupo A mostró una mejora de Tegner de 1,19 (IC 95%: 1,06-1,31), mientras que el grupo B promedió 0,61 (IC 95%: 0,43-0,80) (p<0,001). La edad ≥80 años fue un factor de riesgo independiente para una menor mejoría de Tegner. En el KSSc, el grupo A mejoró 43 puntos (IC 95%: 40,82-46,14), mientras que el grupo B mostró un mayor aumento de 53 puntos (IC 95%: 49,74-57,80). Ajustado por factores de confusión, aquellos pacientes mayores de 80 años mostraron una mejora en KSSc significativamente mayor (12,8 puntos). Para el KSSf, el grupo A mejoró en 33,91 puntos (IC 95%: 31,07-36,75) y el grupo B en 15,57 puntos (IC 95%: 11,78-19,35). Ajustado por factores de confusión, los pacientes≥80 años tuvieron menos mejoría que los<80 (19 puntos).

ConclusionesLos pacientes sometidos a RTR experimentaron mejoras en los parámetros de actividad física y funcional. Si bien estas mejoras se observaron en toda la población, fueron más notables en los pacientes menores de 80 años.

According to study estimations, the global population of adults over 65 years of age is projected to double to approximately 1.5billion by 2050, and the number of people over 80 years of age is projected to triple between 2019 and 2050, reaching 426million.1 This demographic shift is accompanied by higher quality of life expectations among older adults, who aspire to maintain an active lifestyle and continue participating in their professional lives.2,3

Total knee replacement (TKR) is a safe and reliable surgical procedure for patients with advanced knee osteoarthritis seeking pain relief, restoration of function, and improved quality of life.3–5 The demand for joint replacement surgeries has grown exponentially and is expected to continue increasing in upcoming years, with an estimated projection of 791,760 TKRs per year by 2030 in the US alone.6

A crucial determinant of patients’ quality of life is their ability to engage in physical and recreational activities, which is a common concern among patients considering TKR.7 Although there is literature demonstrating improved functional and physical activity capacity after TKR, there is currently no consensus on the influence of age on these outcomes, and whether patients and physicians should consider this when determining the optimal timing of surgery.8–11

The primary objective of this study was to evaluate whether there are differences between preoperative and postoperative physical activity levels based on age. As secondary objectives, we aimed to evaluate the preoperative and postoperative variation in pain and preferred types of physical activities in the two study groups.

Materials and methodsA retrospective analysis was conducted on a cohort of patients who underwent TKR at our institution between January 2016 and December 2019. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards recognised by the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institution's Ethics Committee (CEPI #7101). Inclusion criteria were patients older than 65 years of age with a preoperative diagnosis of unilateral primary knee osteoarthritis. Patients with bilateral TKR; tumours; revision surgery; fractures, or a history of prior surgery were excluded from the study. All relevant information related to the study was prospectively documented in the electronic medical record system and reviewed by the researchers. Patients were stratified into two groups based on age: Group A (65–79 years of age) and Group B (80 years of age or older).

At the final consultation, during the week prior to the procedure, parameters corresponding to body mass index (BMI); activities of daily living (ADL)12; the age-adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index (ACCI)13 to assess frailty, and the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score were recorded.14 The preoperative functional assessment included the two original components of the KSS, its clinical (KSSc) and functional (KSSf) subscales,15 the Tegner scale,16 the 2011 version of the KSS,17 and pain assessment using the visual analogue scale (VAS).

All surgeries were performed in the operating room with laminar flow, under hypotensive spinal anaesthesia and antibiotic prophylaxis (cefazolin at anaesthesia induction and three doses of 1μg in the immediate postoperative period). The approach used in all cases was a medial parapatellar approach, without the use of a haemostatic cuff or postoperative drainage. All prostheses were posteriorly stabilised, cemented, and mechanically aligned. Robotic assistance was not used in any cases. The rehabilitation protocol included full mobilisation with a walker starting on the first postoperative day. Patients gradually resumed normal daily activities over the following weeks based on their clinical and radiographic progression, assessed by immediate postoperative and follow-up radiographs (frontal and profile) obtained at 1, 6, and 12 months postoperatively.

To monitor the postoperative clinical course, senior surgeons performed assessments using the original KSS, the 2011 modified KSS, the Tegner score, and the VAS between 10 and 12 months after surgery. For statistical analysis, continuous variables were expressed as medians and standard deviations, or as means and interquartile ranges, depending on their distribution. Categorical variables were presented as proportions and relative frequencies. Student's t test with a 95% confidence interval was used to determine differences between groups for continuous variables, while the Mann–Whitney test was used when data did not follow a normal distribution.

A linear regression model was applied to assess potential confounding variables related to the primary outcome (delta Tegner, i.e., the difference between the postoperative and preoperative outcome) between patients older and younger than 80 years of age. Crude and adjusted coefficients were reported, considering confounding factors. Confounding factors considered were BMI, sex, ADL, ASA, and ACCI. Statistical analysis was performed using STATA® version 17 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Statistical significance was defined as a p value less than .05.

ResultsA total of 450 patients were evaluated (group A=245; group B=167). Thirty-eight patients were excluded for not completing the outcome assessment at 1-year follow-up (two patients died from causes unrelated to surgery, one from each group; the remaining patients were unable to complete follow-up because they lived in locations far from the institution).

Group A had a mean age at surgery of 73.5 years (SD: 3.04), and group B had a mean age of 83.3 years (SD: 2.80). The mean BMI in group A was 31.7 (SD: 5.23) and in group B, 28.7 (SD: 4.52) (p<.001). The demographic data for both groups are detailed in Table 1.

Patients’ demographic data.

| All (N=412) | Group A (N=245) | Group B (N=167) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 77.4 (5.64) | 73.5 (3.04) | 83.3 (2.80) | <.001 |

| Right side | 220 (53.4%) | 135 (55.1%) | 85 (50.9%) | .46 |

| Men | 153 (37.1%) | 85 (34.7%) | 68 (40.7%) | .255 |

| BMI | 30.5 (5.16) | 31.7 (5.23) | 28.7 (4.52) | <.001 |

| ADL | 5.00 [5.00;6.00] | 5.00 [5.00;6.00] | 5.00 [5.00;6.00] | .108 |

| ACCI | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 4.00 [3.00;5.00] | 5.00 [4.00;6.00] | <.001 |

| ASA | 2.00 [2.00;3.00] | 2.00 [2.00;3.00] | 2.00 [2.00;3.00] | .146 |

| Kellgren–Lawrence | .022 | |||

| 2 | 14 (3.40%) | 7 (2.86%) | 7 (4.19%) | |

| 3 | 130 (31.6%) | 90 (36.7%) | 40 (24.0%) | |

| 4 | 268 (65.0%) | 148 (60.4%) | 120 (71.9%) | |

Group A: patients aged 65–79 years; Group B: patients aged 80 or older.

ACCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index; ASA: American Association of Anaesthesiologists score; ADL: activities of daily living; BMI: body mass index.

A graphical analysis was performed to investigate the correlation between the Tegner delta and patient age (Fig. 1). Due to the linear correlation observed, a cut-off point of 80 years was established to separate the two patient groups. A linear regression analysis was performed separately for each group (Table 2). When comparing the two, it was evident that patients in Group B demonstrated significantly less improvement in the Tegner score compared to their younger counterparts, with a difference of .58 points. To investigate whether this difference was influenced by patient characteristics such as BMI, sex, ADL, ASA, and ACCI, a linear regression analysis was performed. The results showed that age over 80 years was an independent risk factor for less improvement in the Tegner score, with a decrease of .42 points compared to patients younger than 80 years.

Analysis of the variation in pre- and postoperative functional and pain scores.

| All (N=412) | Group A (N=245) | Group B (N=167) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tegner pre. | .55 (.86) | .73 (.84) | .23 (.80) | <.001 |

| Tegner post. | 1.49 (1.11) | 1.92 (.93) | .77 (1.01) | <.001 |

| Delta Tegner | .98 (.98) | 1.19 (.88) | .61 (1.03) | <.001 |

| KSSc pre. | 39.5 (17.1) | 40.8 (16.4) | 37.7 (18.0) | .075 |

| KSSc post. | 87.4 (13.8) | 84.9 (12.6) | 91.6 (14.8) | <.001 |

| Delta KSSc | 47.3 (21.1) | 43.5 (19.3) | 53.8 (22.5) | <.001 |

| KSSf pre. | 46.8 (15.7) | 46.8 (16.7) | 46.7 (14.1) | .956 |

| KSSf post. | 76.6 (20.6) | 82.8 (17.6) | 66.1 (21.2) | <.001 |

| Delta KSSf | 27.1 (22.6) | 33.9 (20.6) | 15.6 (21.1) | <.001 |

| VAS pre. | 7.13 (2.01) | 7.17 (2.23) | 7.06 (1.57) | .602 |

| VAS post. | .88 (1.35) | 1.07 (1.32) | .55 (1.34) | n.s. |

| VAS Delta | 6.25 (2.25) | 6.10 (2.47) | 6.51 (1.82) | .089 |

Group A: patients aged 65–79 years; Group B: patients aged 80 or older.

VAS: visual analogue scale; KSS: Knee Society score; pre: preoperative; post: postoperative.

Similar to the findings of the Tegner behavioural analysis, a non-linear correlation was observed in KSSc scores (Fig. 2). Patients older than 80 years of age showed significantly greater improvement in KSSc compared to those younger than 80 years of age, with a difference of 12.8 points after adjusting for confounding factors (Table 2).

Finally, the functional outcomes of the KSSf were examined, revealing less improvement in patients older than 80 years of age (Fig. 3). After adjusting for confounding factors, we observed that the improvement was 19 points lower in those older than 80 years of age compared to those younger than 80 years of age (Table 2).

Secondary objectivesOn analysing the change in the VAS, it was found that both groups experienced a substantial decrease in reported pain after surgery, with no statistically significant differences between the two groups. The overall VAS change (delta) was 6.25 points (SD: 2.25); group A reported a delta VAS of 6.10 (SD: 2.47), and group B reported a delta VAS of 6.51 (SD: 1.82), indicating similar improvements (p=.089).

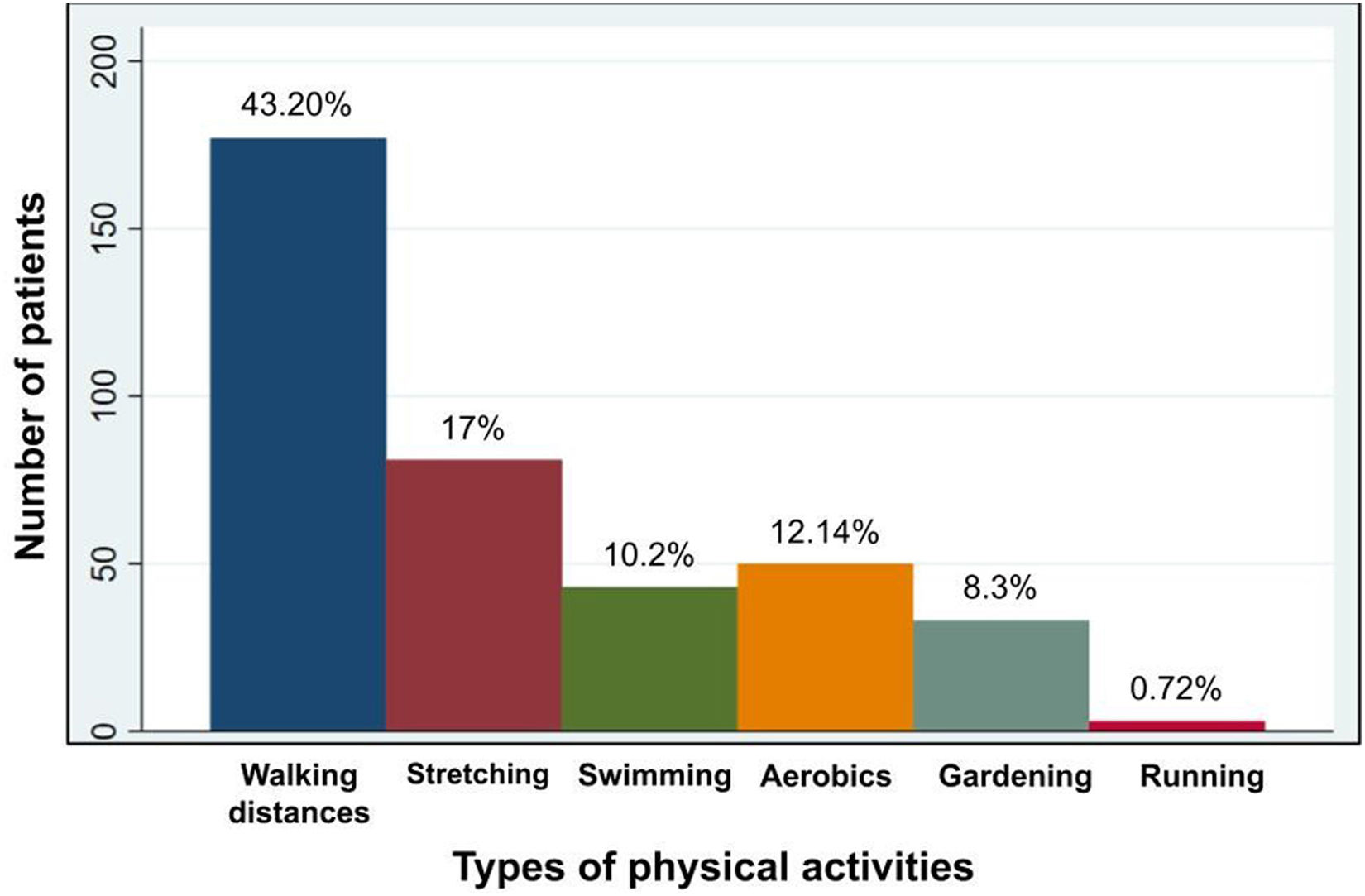

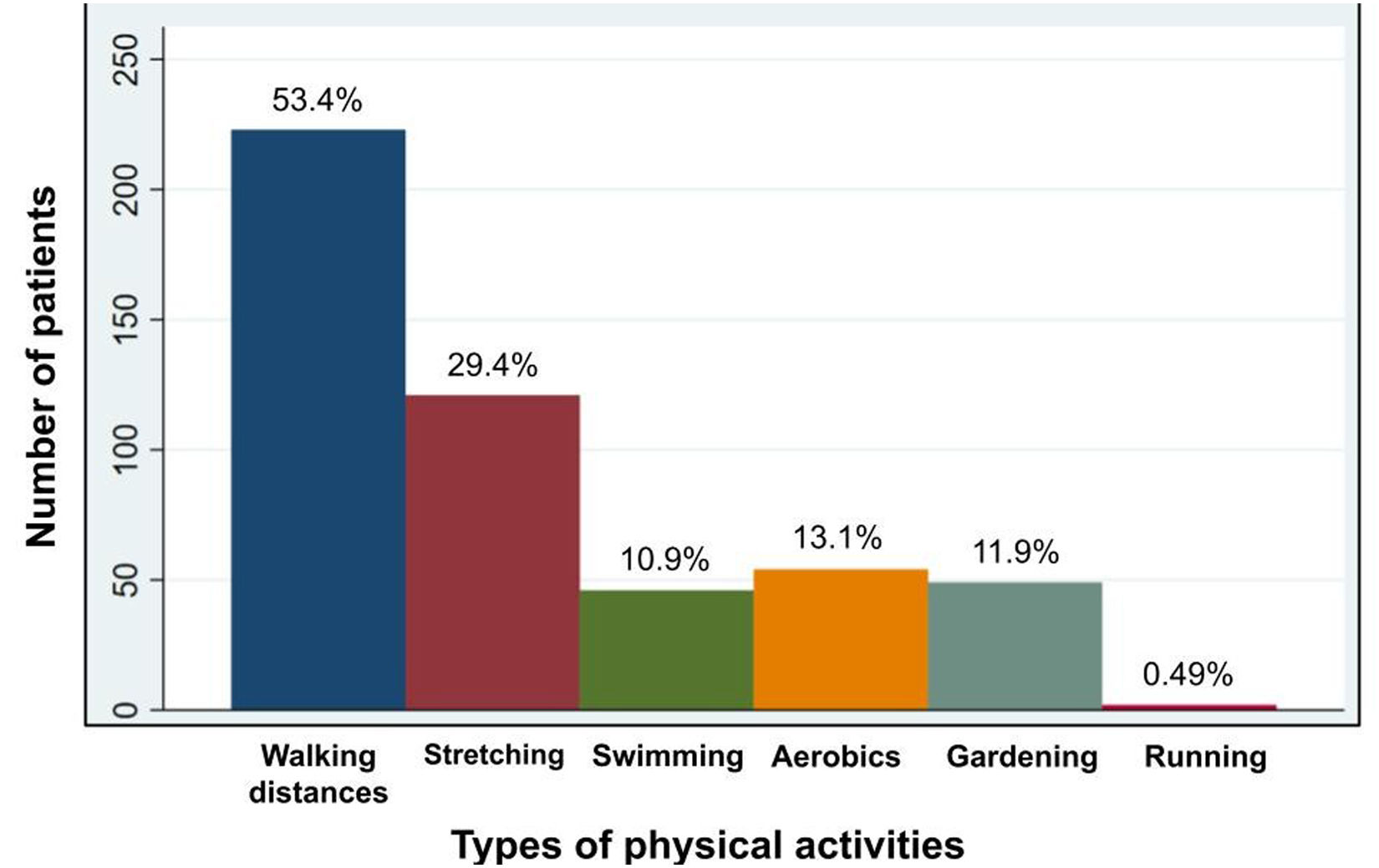

Finally, the main physical activities reported by the patients within the 2011 KSS were recorded, both before and after surgery (Figs. 4 and 5), where an increased tendency towards low-impact activities is evident.

DiscussionSignificant improvements in physical and functional activity parameters, accompanied by a reduction in pain, were observed in the study among patients undergoing TKA. These improvements were evident across the entire study population; however, they were particularly notable in patients younger than 80 years of age compared to those older than 80 years of age.

It has been observed that people with advanced osteoarthritis, including those undergoing TKA, often do not meet the physical activity guidelines recommended by public health entities.18 Kersten et al. reported that nearly half of these patients did not meet physical activity guidelines and were less active compared to a control group.19 Numerous studies have consistently demonstrated the beneficial relationship between regular exercise and cardiovascular health, leading to a reduction in overall mortality and morbidity.20

The successful results of TKA in pain relief and restoration of function have been widely documented. Furthermore, studies have reported a positive impact on health, fitness, and a reduced risk of coronary artery disease in patients who were able to resume activities shortly after surgery.21 Therefore, it is crucial to assess our patients’ ability to return to sports and an active lifestyle.

Hanreich et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis covering 25 studies involving 6035 TKR cases.8 Of these studies, four evaluated the Tegner score and reported that all patients maintained or increased their physical activity level after surgery. However, when considering the studies with the highest level of evidence included in this review, it is worth noting that, while overall they agree on the positive impact of TKR, not all of them agree with our findings on the influence of age. For example, Vielgut et al. found, as in our population, that age was identified as a significant negative predictor for both preoperative and postoperative22 Tegner scores. Furthermore, Hepperger et al. conducted a study evaluating 200 patients aged 55–90 years undergoing TKR.9 They observed a significant increase in the Tegner score from the preoperative state to 24 months after surgery. Despite finding a significant negative correlation between age and Tegner score throughout the evaluation period (p<.010), when categorising patients into 2 age groups (“young”=55–72 years; “old”=73–90 years), they found no statistically significant differences. Another study included in this review was conducted by Long et al. in 2014, who reviewed a series of 88 patients who underwent TKR to assess long-term survival.23 They also reported an overall improvement in Tegner score among surgically treated patients, however, this study did not specifically evaluate the influence of age on outcomes.

Regarding the KSS, in their review of 826 patients undergoing TKA, Seo et al., istratified the patients into an octogenarian group (over 80 years of age) and a younger group (65–70 years of age).10 They found that both groups demonstrated improvement in the KSSc score, with no significant differences between them. However, in the KSSf score, the octogenarian group did not show significant improvement compared to the younger group. Kosse et al. conducted a randomised clinical trial with 42 patients between 40 and 70 years of age, divided into two study groups, comparing a specific implant placement method with the traditional method.24 When analysing preoperative KSS scores, they observed significant improvement at 12 months with no differences between the groups.

The secondary objective of the study was to evaluate the change in pain measured by the VAS and to identify the most frequently reported physical activities. The hypothesis was that patients with less pain would have fewer limitations in physical activity. Interestingly, no significant differences in pain reduction were observed based on age. Similar findings were reported by Hepperger et al., who observed a significant decrease in VAS pain scores postoperatively, with no correlation between age and pain.9 Vielgut et al. in their study population also found a significant improvement in preoperative pain status at the final follow-up.22

Regarding the activities most frequently reported by patients, a consistent preference for low-impact activities was identified in our population (Figs. 4 and 5), which aligns with the findings of Witjes et al. in their systematic review.25 Furthermore, we observed an increase in the percentage of patients participating in each of these activities after surgery, as recommended by the consensus reached during the 2007 annual meeting of the American Society of Hip and Knee Surgeons. Surgeons generally agreed not to restrict activities such as walking and cycling on flat surfaces, swimming, stair climbing, and golf, while advising against high-impact activities such as running, jogging, and skiing on difficult terrain, especially in patients with no prior experience.26

Certain study limitations need to be acknowledged. First, its retrospective nature presents inherent limitations in its design. Furthermore, the lack of an objective and validated tool to assess the quality of physical activity, including factors such as competition level, weekly practice hours, or the specific timing of return to sports, as well as the lack of assessment of psychological factors that may influence these outcomes, limits the comprehensive evaluation of physical activity outcomes. In turn, the Tegner scale likely has shortcomings in correctly assessing and accurately discriminating patients with severe knee osteoarthritis and those postoperatively with TKR.

ConclusionsAccording to the study's findings, age should be carefully considered when deciding the timing of surgery, particularly in younger patients who have high expectations of returning to their preoperative athletic performance level. Delaying the procedure in these cases may result in less favourable functional outcomes after surgery.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence iv.

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted in keeping with the ethical standards recognised by the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval by the Ethics Committee of the Italian Hospital in Buenos Aires (CEPI #7101).

FundingThis study received no funding from any public sector agencies, the commercial sector or non-profit entities.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.