Ankle sprains can lead to chronic lateral ankle instability (CLAI) in 10-50% of cases. While the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) is traditionally considered the primary structure affected, recent studies indicate a high incidence of combined injuries to the ATFL and the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL). Given the importance of the CFL, this study aims to evaluate the biomechanical efficacy of double tendon graft reconstruction of the ATFL and CFL in cases of CLAI.

Materials and methodsThis biomechanical study on cadaveric ankles compares two techniques: anatomical reconstruction using a double graft for both the ATFL and CFL versus isolated anatomical reconstruction of the ATFL with a single graft. Stability was assessed using specific examination maneuvers (anterior drawer, forced varus, and pivot shift) with an arthrometer measuring angular displacement across three spatial planes (horizontal, coronal, and sagittal). Four models were analyzed: intact ankle, sectioning of the ATFL and CFL, double graft reconstruction of the ATFL and CFL, and single graft reconstruction of the ATFL.

ResultsThe results showed no significant differences between the double graft reconstruction and the intact ankle. Comparing the double graft with the single graft reconstruction revealed statistically significant differences, favoring the double graft for greater angular stability in the coronal plane during forced varus and external rotation maneuvers.

ConclusionsDouble graft reconstruction of the ATFL and CFL provides greater angular stability compared to isolated ATFL reconstruction, demonstrating significant benefits in lateral and rotational stabilization of the ankle in CLAI cases.

El esguince de tobillo puede derivar en inestabilidad lateral crónica de tobillo (ILCT) en el 10-50% de los casos. Aunque clásicamente se considera que el ligamento peroneoastragalino anterior (LPAA) es el principal afectado, investigaciones recientes muestran una alta incidencia de lesiones combinadas del LPAA y el ligamento peroneocalcáneo (LPC). Dada la importancia del LPC, el objetivo es evaluar la eficacia biomecánica de la reconstrucción con plastia tendinosa doble del LPAA y LPC en casos de ILCT.

Material y métodosSe trata de un estudio biomecánico en tobillos de cadáver que compara dos técnicas: la reconstrucción anatómica con plastia doble de ambos ligamentos (LPAA y LPC) frente a la reconstrucción anatómica aislada del LPAA con plastia única. Se evaluó la estabilidad mediante maniobras específicas de exploración (cajón anterior, varo forzado y maniobra de pivote) utilizando un artrómetro que mide el desplazamiento angular en los 3 planos del espacio (horizontal, coronal y sagital). Se analizaron 4 modelos: tobillo intacto, sección de LPAA y LPC, reconstrucción con plastia doble del LPAA y LPC y reconstrucción con plastia única del LPAA.

ResultadosLos resultados mostraron que no había diferencias entre la plastia doble y el tobillo intacto. Al comparar la plastia doble con la plastia simple, encontramos diferencias estadísticamente significativas a favor de una mayor estabilidad angular en el plano coronal, con las maniobras de varo forzado y rotación externa.

ConclusionesLa reconstrucción con plastia doble del LPAA y LPC ofrece mayor estabilidad angular en comparación con la plastia aislada del LPAA, mostrando beneficios significativos en la estabilización lateral y rotacional del tobillo con sección del LPPA y LPC.

Ankle sprains can lead to chronic lateral ankle instability (CLAI) in 10%–50% of cases. 1 It has been generally assumed that most injuries involve the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) alone, with combined injuries to the ATFL and calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) being less common.2 However, more recent studies have found combined injuries to the ATFL and CFL in 64% of patients with CLAI symptoms.3 The CFL appears to play a key role in varus stabilisation not only of the talocrural joint but also of the subtalar joint. 4 Injury to the CFL can lead to an increased range of motion in inversion and eversion, which can alter the normal weight-bearing mechanics of the subtalar joint.5,6

Currently, the gold standard for surgical treatment of CLAI remains the anatomical repair technique described by Bröstrom and later modified by Gould, which is based on repair of the ATFL with local tissue remnant and augmentation with the extensor retinaculum.7,8

The common origin of ATFL and CFL has led some authors to advocate isolated repair of the ATFL as the sole treatment for CLAI.9,10 However, this may be insufficient in patients with poor tissue remnant, ligamentous hypermobility, or high functional demands, where reconstruction techniques with grafting are more advisable.11,12

In the literature, we find evidence of the role that the CFL plays in the stability of the tibiotalar and subtalar joints. However, there are no high-quality studies supporting the biomechanical efficacy of combined ATFL and CFL repair in CLAI. The objective of this study was to analyse whether anatomical reconstruction with tendon grafting of the ATFL and CFL was superior to isolated ATFL reconstruction after transection of both ligaments in a cadaveric model at time zero.

Material and methodsThis was an experimental, comparative, and cross-sectional study where the study units were anatomical ankle specimens from frozen cadavers. The angular stability of the tibiotalar joint was explored by performing anterior drawer manoeuvres, forced varus, and pivot manoeuvres after reconstruction of the lateral ankle ligament complex using two different surgical techniques. The study was conducted in four consecutive phases based on the four study models: intact ATFL and CFL (Fig. 1); combined ATFL and CFL transection after reconstruction with double ATFL and CFL grafting; and anatomical reconstruction with a single ATFL graft. To estimate the sample size, we used the formula applicable to infinite populations: n=(Z_α^2 PQ)/e^2). A confidence level of 95% and a maximum accepted estimation error (e) of .2 were used; this resulted in an estimated sample of 24 ankle specimens.

Anatomical detail of the lateral ankle ligament complex. The ATFL is marked with * and the CFL is marked with°. A. Normally positioned peroneal tendons. B. The peroneal tendons have been removed; note how the CFL runs in a more vertical position and plays a role in the stability of the tibiotalar and subtalar joints.

For sample selection, we excluded ankles with a history of previous local surgery, joint stiffness, significant anatomical deformity, and a history of metastatic cancer or rheumatic disease. A total of 24 ankles were used (12 left and 12 right); 11 belonged to women and 13 to men. The median age of the donors at the time of death was 73 (48–95) years. All of them maintained a tibial length of at least 15cm from the tibiotalar joint. The anatomical specimens were obtained according to the programme of the Body Donation Centre at the Complutense University of Madrid.

Two techniques were compared: anatomical reconstruction with a double graft of the ATFL and CFL (Fig. 2) and anatomical reconstruction with a single graft of the ATFL (Fig. 3). In both cases, an autologous Extensor hallucis longus (EHL) graft was used. These techniques were performed sequentially in each of the specimens following the steps described below. After sectioning the ATFL and CFL at their fibular origin, both were reconstructed with a double graft using an autologous graft of the EHL tendon, which was extracted at a minimum length of 150mm. The end of the graft was prepared with a high-strength Fiberloop #0 suture (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA), and the opposite end with a 2/0 absorbable suture. After identifying the ATFL and CFL origin traces in the fibula, a 6×15mm bone tunnel was made in an anteroposterior direction at a 45° angle, followed by a blind half-tunnel in the talar neck over the ATFL insertion trace (25×5mm). The CFL insertion trace in the calcaneus was identified using the peroneal tubercle as a reference; a 5.5×25mm blind tunnel was prepared through a small posterior skin incision. A Tightrope cortical tenosuspension system (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA) was used to secure the graft to the fibula. The anterior distal end of the graft was secured to the talar footprint with a 4.75mm SwiveLock implant (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA), maintaining the ankle in neutral eversion and dorsiflexion. Finally, the second, more posterior end was passed deep to the peroneal tendons and strapped to the calcaneus with a 5.5mm SwiveLock implant (Arthrex, Naples, FL, USA), maintaining the ankle in slight dorsiflexion and eversion. The procedure was completed by tensioning the tenosuspension system on the posterior cortex of the fibula. To study the anatomical model with a single ATFL graft, we started from the previous reconstruction and secured the graft in the fibular tunnel with a biotenodesis screw .5mm larger than the diameter of the fibular tunnel; in this way, we achieved stable fixation of both the fibular and talar ends. Finally, to obtain the desired model, the peroneocalcaneal fasciculus was sectioned from the graft, thus simulating the incompetence of the CFL with an isolated ligamentous reconstruction of the LATFL.

The angular stability of the talocrural joint was measured using an arthrometer specifically designed to record angular displacements in the three spatial planes (horizontal, coronal, and sagittal). The device combined a gyroscope and a triaxial accelerometer connected to an Arduino Mega 2560 microcontroller with the Mpu6050 sensor, which records and processes the angular displacement in real time and in the three planes, using a fusion algorithm and specialised software.13–15 The anatomical specimen is secured with a clamp anchored to the distal tibia, and the sensor is attached to the talus using two Kirchner wires positioned in the neck of the talus, along its longitudinal axis.

The ankle specimens were prepared in keeping with a uniform dissection protocol, and all examination manoeuvres were performed by a single examiner to ensure consistency in data collection. The evaluation of each specimen was divided into four phases: intact ATFL and CFL; complete transection of both ligaments; reconstruction of the ATFL and CFL, and reconstruction of the ATFL with transection of the CFL according to the techniques described above. The manoeuvres used to assess joint stability included the anterior drawer (AD), which measures anterior translation of the talus relative to the tibia and primarily evaluates the resistance exerted by the ATFL;7 the varus stress test (VF), which assesses lateral stability by applying a varus force, thereby allowing observation of the lateral resistance offered by the CFL16; and the pivot manoeuvre (PM), which measures internal rotation of the talus without anterior translation, with the examiner applying a rotational force to the calcaneus and the tibia fixed in position. 17 All manoeuvres were performed by the same examiner, simulating standard office settings. A previously described angular arthrometer was used to record the data. Each measurement was performed after calibrating the sensor in all 3 planes, establishing references on the horizontal axis of the table and in the neutral position of the support jaw. Rotations and displacements were defined as follows: in the axial plane, external rotation was assigned positive values and internal rotation negative values; in the coronal plane, inversion was recorded as positive and eversion as negative; and in the sagittal plane, plantar flexion was recorded as positive and dorsiflexion as negative. Each variable was initially recorded at rest and then when the anatomical specimen underwent the 3 examination manoeuvres (AD, VF, and PM) with the sensor positioned on the talus, assessing the angular stability of the tibiotalar joint. The displacement sign indicated the direction of joint movement, and the angular stability value was calculated as the difference between the final displacement after the manoeuvre and the resting position. To ensure accuracy, three consecutive measurements of each variable were taken during the same manoeuvre by the same examiner, and the arithmetic mean of these three values was used for statistical analysis.

Data were processed using R software version 4.4.1 (R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Since the n value was not very large and the variations did not exactly follow a normal distribution, the Student's t and Wilcoxon statistical tests were applied to compare the angular variables in the different models. Student t and Wilcoxon test results were considered reliable if they coincided with those of the nonparametric Wilcoxon test. A p value of <.05 was assumed to be statistically significant. The analysis included the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), which assesses intraobserver variability.

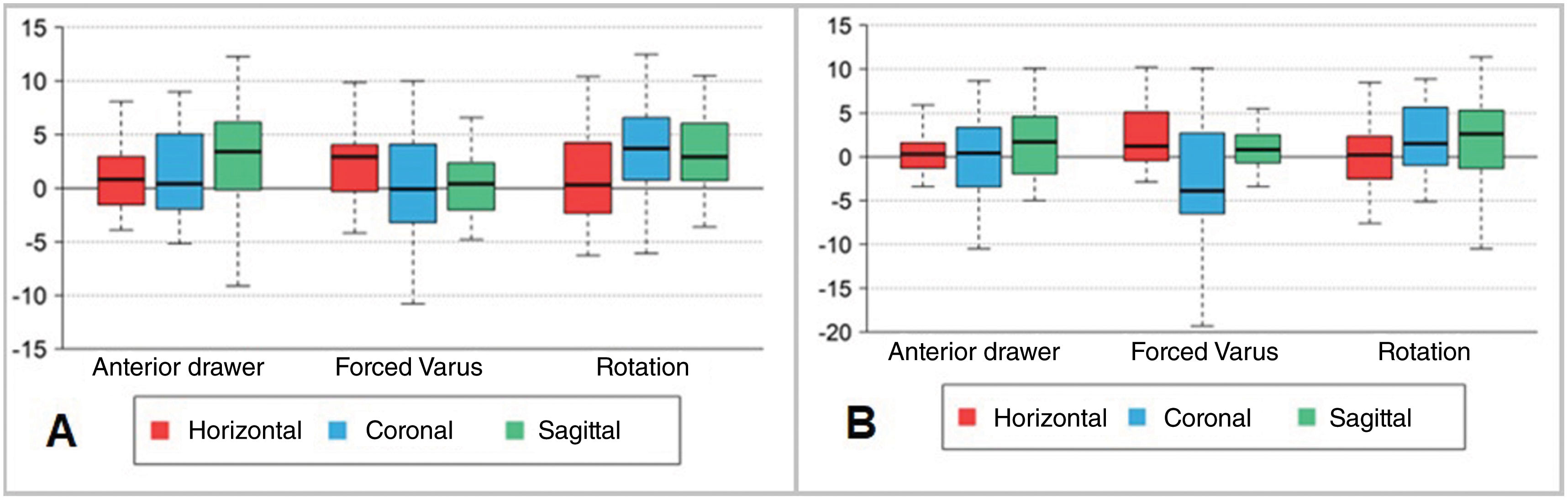

ResultsTable 1 shows the angular displacement of the talus, indicating the mean and standard deviation (SD) with each exploration manoeuvre performed (AD, VF, PM) for each of the anatomical models described: intact ankle, ATFL and CFL section, double ATFL and CFL ligament graft, and single ATFL ligament graft (Fig. 4,).

Descriptive statistics of the angular displacement of the sensor, measured in degrees, located on the talus.

| Full | Sectioned | Double Plasty | Single Plasty | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anterior drawer | ||||

| Horizontal | 3.96±3.59 | 3.58±3.08 | 2.84±2.53 | 3.30±3.00 |

| Coronal | 9.35±10.1 | 11.2±12.3 | 9.32±13.6 | 9.5±11.0 |

| Sagittal | 12.8±5.05 | 13.5±6.27 | 10.3±7.79 | 10.4±4.91 |

| Forced varus | ||||

| Horizontal | 4.57±4.00 | 3.41±2.89 | 1.94±1.68 | 2.23±2.41 |

| Coronal | 11.0±11.6 | 16.4±12.4 | 9.9±12.9 | 14.8±17.2 |

| Sagittal | 4.91±3.56 | 5.52±4.20 | 6.27±9.50 | 3.98±3.17 |

| Pivot | ||||

| Horizontal | 7.54±5.55 | 12.6±6.90 | 6.23±4.91 | 7.46±5.32 |

| Coronal | 11.7±13.4 | 11.0±10.0 | 9.02±13.0 | 10.0±9.8 |

| Sagittal | 11.5±6.63 | 13.5±8.53 | 7.94±7.25 | 9.18±5.56 |

The data are presented with the mean and standard deviation. Data are grouped according to angular displacement in the three spatial planes (horizontal. coronal, and sagittal) for each of the exploration manoeuvres (anterior drawer manoeuvre, forced varus, and pivot or internal rotation manoeuvre) and in the four anatomical models described (intact lateral ligamentous complex, section of the ATFL and CFL, double ATFL and CFL plasty, and ATFL plasty).

Table 2 shows the results of comparing the models with intact ATFL and CFL ligaments versus section of the same.

Comparison of the angular displacement of the talus (tibiotalar joint) with intact ATFL and CFL, versus their section, after the application of the stability exploration manoeuvres (anterior drawer manoeuvre [AD], forced varus [VF], and rotation or pivot manoeuvre [PM]), in the three spatial planes (horizontal [H], coronal [C], and sagittal [S]).

| Manoeuvre | Plane | Mean (95% CI) | Median (95% CI) | pa | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AD | H | .38 (−1,17.1.93) | .07 (−1.5. 1.90) | 0618 | .964 |

| C | −1.80 (−4.94, 1.33) | −1.60 (−3.75, .75) | .245 | .200 | |

| S | −.71 (−3.35, 1.93) | −1.25 (−3.30, 2.05) | .583 | .543 | |

| VF | H | 1.16 (−.68, 3.00) | 1.10 (−.80, 3.00) | .204 | .280 |

| C | −5.40 (−9.44, −1.36) | −4.92 (−8.55, −2.60) | .011 | .003 | |

| S | −.61 (−2.22, 1.00) | −.28 (−2.35, 1.15) | .442 | .616 | |

| PM | H | −5.10 (−7.54, −2.65) | −4.68 (−7.60, −2.40) | <.001 | <.001 |

| C | .63 (−2.88, 4.14) | 1.03 (−1.75, 3.75) | .713 | .345 | |

| S | −2.03 (−4.14, .09) | −2.01 (−4.45, .30) | .059 | .083 |

In the comparative analysis of intact ATFL and CFL ligaments versus double ATFL and CFL ligaments (Table 3), there were no statistically significant differences between the two models, except for a lower displacement with the double ligament graft in the horizontal plane during the forced varus manoeuvre and in the sagittal plane during the pivot manoeuvre (Fig. 5).

Comparison between the angular displacement of the talus (tibiotalar joint) with intact ATFL and CFL, versus double ATFL and CFL plasty, after the application of stability exploration manoeuvres (anterior drawer manoeuvre [AD], forced varus [VF] and rotation or pivot manoeuvre [PM]), in the 3 spatial planes (horizontal, coronal and sagittal).

| Manoeuvre | Plane | Mean (95% CI) | Median (95% CI) | pa | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole ATFL and CFL vs. double ATFL and CFL plasty | |||||

| AD | Horizontal | 1.12 (−.32. 2.55) | .95 (−.55, 2.65) | .120 | .191 |

| Coronal | .03 (−3.90, 3.95) | .55 (−1.95, 3.65) | .989 | .622 | |

| Sagittal | 2.51 (−.87, 5.90) | 3.22 (.30, 5.80) | .138 | .038 | |

| VF | Horizontal | 2.63 (1.02, 4.24) | 2.60 (.95, 4.20) | .003 | .003 |

| Coronal | 1.09 (−1.87, 4.05) | .36 (−2.00, 3.85) | .453 | .715 | |

| Sagittal | −1.36 (−4.77, 2.06) | .20 (−1.75, 1.85) | .419 | .855 | |

| PM | Horizontal | 1.31 (−.78. 3.40) | 1,5 (−1.00, 3.45) | .206 | .370 |

| Coronal | 2.65 (−2.06, 7.36) | 3.55 (.30, 6.20) | .255 | .038 | |

| Sagittal | 3.54 (1.23, 5.85) | 3.33 (1.20, 5.55) | .004 | .001 | |

| Sectioned ATFL and CFL vs. double ATFL and CFL plasty | |||||

| AD | Horizontal | .74 (−.81. 2.29) | .74 (−.85, 2.40) | .334 | .301 |

| Coronal | 1.83 (−3.20, 6.86) | 2.47 (−.60, 6.00) | .458 | .126 | |

| Sagittal | 3.22 (.24, 6.21) | 4.33 (−.10, 6.25) | .036 | .061 | |

| VF | Horizontal | 1.47 (.16, 2.77) | 1.40 (.05, 2.80) | .029 | .037 |

| Coronal | 6.49 (1.85, 11.1) | 6.20 (3.25, 9.7) | .008 | .001 | |

| Sagittal | −.75 (−4.10, 2.61) | .40 (−1.45, 1.95) | .648 | .670 | |

| PM | Horizontal | 6.41 (3.98, 8.84) | 6.33 (4.10, 8.70) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Coronal | 2.02 (−3.35, 7.39) | 2.48 (−.05, 6.50) | .443 | .052 | |

| Sagittal | 5.57 (2.92, 8.21) | 5.40 (2.50, 8.40) | <.001 | <.001 | |

The lower part of the table shows a comparison of sectioned APL and PCL versus a double plasty of both.

Graphical description in the form of a box plot of the comparison between the angular displacement of the talus (tibiotalar joint) with intact ATFL and CFL versus reconstruction with a plasty after applying the stability exploration manoeuvres (anterior drawer manoeuvre, forced varus, and rotation or pivot manoeuvre) in the 3 spatial planes (horizontal, coronal, and sagittal). A. Double ATFL and CFL plasty. B. Single ATFL plasty.

In the comparative analysis of the intact ATFL and CFL versus the simple ATFLplasty (Fig. 5), statistically significant differences were evident in the angular displacement of the talus in the coronal planes during the forced varus manoeuvre, favouring greater displacement in the model with the simple ATFL plasty (Table 4).

Comparison of the angular displacement of the talus (tibiotalar joint) with intact ATFL and CFL versus a simple ATFL plasty, after the application of stability exploration manoeuvres (anterior drawer manoeuvre [ADM], forced varus [VF], and rotation or pivot manoeuvre [PM]) in the three spatial planes (horizontal, coronal, and sagittal).

| Manoeuvre | Plane | Mean (95% CI) | Median (95% CI)) | pa | pb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole ATFL and CFL vs. simple ATFL plasty | |||||

| AD | Horizontal | .66 (−.92, 2.23) | .30 (−.90, 2.15) | .397 | .738 |

| Coronal | −.15 (−3.61, 3.30) | .15 (−2.35, 2.55) | .928 | .879 | |

| Sagittal | 2.40 (−.03. 4.83) | 1.86 (−.20, 4.45) | .053 | .086 | |

| VF | Horizontal | 2.33 (.71, 3.96) | 2.17 (.20, 4.10) | .007 | .023 |

| Coronal | −3.77 (−7.52, −.01) | −3.27 (−7.15, .25) | .049 | .061 | |

| Sagittal | .93 (−.50, 2.36) | .78 (−.40, 2.10) | .191 | .166 | |

| PM | Horizontal | .08 (−1.70, 1.87) | .10 (−1.85. 1.80) | .924 | .891 |

| Coronal | 1,0 (−2.26, 5.65) | 1.82 (−.20, 3.95) | .384 | .075 | |

| Sagittal | 2.30 (.16, 4.43) | 2.45 (.35, 4.45) | .036 | .021 | |

| Sectioned ATFL and CFL vs. simple ATFL plasty | |||||

| AD | Horizontal | .28 (−1.21, 1.77) | .55 (−.95, 1.55) | .703 | .345 |

| Coronal | 1.65 (−2.68, 5.98) | 2.30 (−.25, 5.45) | .437 | .092 | |

| Sagittal | 3.11 (.43, 5.79) | 3.56 (.40, 6.20) | .025 | .019 | |

| PM | Horizontal | 1.17 (−.04, 2.39) | 1.10 (−.00, 2.15) | .057 | .061 |

| Coronal | 1.63 (−3.80, 7.07) | 2.60 (−1.00, 5.15) | .539 | .126 | |

| Sagittal | 1.54 (.01, 3.07) | 1.25 (.10, 2.50) | .049 | .045 | |

| PM | Horizontal | 5.18 (2.72, 7.63) | 4.80 (2.80, 7.05) | <.001 | <.001 |

| Coronal | 1.07 (−2.77, 4,90) | 1.07 (−0.65, 3.40) | .570 | .223 | |

| Sagittal | 4.32 (1.66, 6.98) | 4.0 (1.55, 6.85) | .003 | .004 | |

The lower part of the table shows a comparison of sectioned ATFL and CFL versus simple ATFL plasty.

In the comparison between the model with double ATFL and CFL versus the simple ATFL plasty (Fig. 6), there were statistically significant differences in the angular displacement of the talus in the coronal plane during the forced varus manoeuvre (Table 5).

Graphical description in the form of a box plot of the comparison between the angular displacement of the talus (tibiotalar joint) with double ATFL and CFL reconstruction versus reconstruction with a single ATFL reconstruction, after the application of stability examination manoeuvres (anterior drawer manoeuvre, forced varus, and rotation or pivot manoeuvre) in the three spatial planes (horizontal, coronal, and sagittal).

Comparison of angular displacement of the talus (tibiotalar joint) with double ATFL and CFL plasty versus simple ATFL plasty, after the application of stability exploration manoeuvres (anterior drawer manoeuvre [ADM], forced varus [VF], and rotation or pivot manoeuvre [PM]) in the three spatial planes (horizontal, coronal, and sagittal).

| Double ATFL and CFL vs. simple ATFL plasty | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manoeuvre | Plane | Mean (95% CI)) | Median (95% CI)) | pa | pb |

| AD | Horizontal | −.46 (−1.82, .90) | −.64 (−1.85, .65) | .489 | .330 |

| Coronal | −.18 (−2.50, 2.14) | −.30 (−2.10, .90) | .875 | .731 | |

| Sagittal | −.11 (−2.76, 2.53) | −.70 (−2.25, 1.25) | .930 | .386 | |

| VF | Horizontal | −.29 (−1.22, .64) | −.22 (−1.20, .80) | .523 | .800 |

| Coronal | −4.86 (−8.15, −1.56) | −3.50 (−6.25, −1.45) | .006 | <.001 | |

| Sagittal | 2.29 (−1.90, 6.47) | .35 (−.85, 1.70) | .269 | .563 | |

| PM | Horizontal | −1.23 (−2.95, .48) | −1.30 (−2.80, .55) | .151 | .151 |

| Coronal | −.96 (−3.26, 1.34) | −1.55 (−3.15, .10) | .398 | .061 | |

| Sagittal | −1.24 (−3.11, .63) | −1.55 (−3.30. .65) | .182 | .168 | |

Finally, we assessed the degree of agreement between the three measurements taken during each exploration manoeuvre on each anatomical model using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). In all the manoeuvres performed, the ICC reached values equal to or very close to 1, which means that the agreement between the measurements was perfect or practically perfect.

DiscussionAnkle sprains are very common injuries, affecting both the ATFL and CFL ligaments in the most severe cases. However, there is no consensus regarding the need to repair or reconstruct the CFL together with the ATFL. This study studies the biomechanical stability offered by lateral ankle ligament reconstruction with a double graft (ATFL and CFL) versus ATFL reconstruction alone. The results of this study guide us to consider anatomical reconstruction with a double graft (ATFL and CFL) as a surgical technique superior to isolated ATFL reconstruction in the management of CLAIs when both ligaments are involved.

Reconstruction techniques are especially relevant in patients in whom direct repair of one or both ligaments is not possible (failed previous repair, lack of quality tissue remnant, ligament hyperlaxity, high functional demands of sports, or obesity).18 It is in these patients that reconstruction of both ligaments appears to provide better functional results19 Previous studies analysing the tibiotalar angular stability provided by ATFL reconstruction have already indicated that it offers resistance and rigidity similar to those of an intact ligament.20 However, there are no studies that validate reconstruction with a double ATFL and CFL reconstruction from a biomechanical perspective. In our study, comparing isolated ATFL reconstruction with a ATFL and CFL reconstruction model, the double ATFL reconstruction demonstrated significantly greater angular stability, especially in the coronal plane during the forced varus manoeuvre. Furthermore, a simple ATFL reconstruction offers some improvement in stability compared to an ankle with sectioned ligaments but it is limited in its ability to control angular displacements in the coronal plane. These findings underscore the fundamental role of the CFL in lateral stabilisation and its contribution to resistance to varus forces, which cannot be replaced by the ATFL. This confirms previous studies that attribute a key role to the CFL in supporting the subtalar and talocrural joints.4–6,21,22 However, we find contradictory views in the literature regarding the need to repair the CFL in CLAI. Several clinical studies report good functional and radiological results, with no statistically significant differences when comparing patients with isolated ATFL repair or reconstruction and patients with repair or reconstruction of both ligaments.10,23 However, the biomechanical study by Kobayashi et al.24 reflects the importance of the CFL in ankle stabilisation, both at the talocrural and subtalar levels, especially under multidirectional loads, without its function being substituted by other ligaments present in the ankle. Similarly, the work of Hunt et al. reflects that the CLA injury, unlike the CLAI injury, significantly increases the inversion of the hindfoot and modifies the load centre on the articular surface, modifying the mechanics of the ankle, which can lead to long-term damage to the articular cartilage.6

Reconstruction of both the ATFL and CFL ligaments with an allograft has proven to provide satisfactory clinical outcomes on the AOFAS and Karlsson-Peterson scales and to objectively improve ankle stability without compromising joint mobility.25,26 These results are similar to the ones obtained in patients with direct repair of both ligaments, but it should be noted that these reconstruction techniques are the only ones possible in patients where there is no good-quality tissue remnant.25 Advances in ankle arthroscopy have led to the development of less invasive ATFL and CFL reconstruction techniques that reproduce the anatomical configuration of the ligaments, with comparable results in terms of stability and shorter recovery times.27 Although clinical outcomes cannot be assessed, our results show that double ATFL and CFL repair restores angular joint stability comparable to that of an intact ankle, although with greater restrictions on varus and internal rotation manoeuvres. This could be related to the eversion of the joint when the graft was tensioned.

This study is not without limitations. Since it is a cadaveric study, we cannot take into account the biological effect of scarring and fibrosis, which contribute to long-term ankle stability. Similarly, we only analysed the intrinsic stability provided by the osteoligamentous structures, without considering muscular stabilisation; both factors may be responsible for attenuating the differences observed in in vivo studies. Furthermore, the evaluation method used was based on examination manoeuvres, which depend on the examiner, without quantifying the force or pressure exerted during these manoeuvres. To minimise the error associated with this circumstance, each measurement was performed by the same observer three times, with intra-observer correlation results very close to 1. This ensured the reliability and consistency of the results. Despite these aspects, the strengths of this study include its rigorously designed, experimental cadaveric study with 24 specimens and its use of an instrument previously validated in ankle biomechanical research. It is the first published study comparing two reconstruction techniques under conditions of combined ATFL and CFL injury, providing relevant information for clinical decision-making in the treatment of chronic ankle instability. Prospective studies are needed to validate these findings in a clinical setting and evaluate the long-term effects of the different ligament reconstruction techniques.

ConclusionsAccording to the results of this study, double ligament reconstruction (ATFL and CFL) offers greater angular stability of the tibiotalar joint compared to single ligament reconstruction (ATFL) after transection of both ligaments in a cadaveric ankle model at time zero.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence III.

AuthorshipAll authors meet the authorship requirements for this study, which was prepared in accordance with the instructions for authors of the REVISTA ESPAÑOLA DE CIRUGÍA ORTOPÉDICA Y TRAUMATOLOGÍA.

Ethical considerationsThis study was conducted in the Department of Human Anatomy and Embryology at the Complutense University of Madrid, in collaboration with the Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology Service of the 12 de Octubre University Hospital and the Orthopaedic Surgery and Traumatology Service of the Fundación Jiménez Díaz University Hospital.

This research was evaluated by the Bioethics Committee of the i+12 Research Institute at the 12 de Octubre University Hospital, and was approved on April 14, 2021.

FundingThis research was funded by the SECOT Foundation's “Research Start-Up Projects” grant, which was announced in 2021

Declaration on the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies in the Writing ProcessDuring the preparation of this work, the authors did not use any type of artificial intelligence or AI-assisted technology.

Conflict of interestsThe author, J. Vilá y Rico, is an international consultant for Arthrex. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Our thanks to the Staff of the Department of Anatomy and Embryology at the Complutense University of Madrid and the technical team of the dissection room.

Arthrex Spain, for the generous provision of the material necessary to carry out the research work.

Also to Ignacio Mahillo Fernández, for his invaluable help with data processing.