The primary objective is to evaluate the clinical and functional outcomes of tape reinforcement in anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstructions, recording complications, as well as the rate of reinterventions and graft failure.

Materials and methodsRetrospective analysis of ACL reconstructions with hamstring (HS) autograft that were reinforced with high-strength tape. We included patients in whom we obtained a graft of HS <8mm or ≥8mm of poor quality. Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and previous activity were recorded. Clinical and functional evaluation were made and postoperative range of motion (ROM), pain, and Lysholm functional scale were recorded. Complication rate, graft failure rate, and reintervention rate were analyzed.

ResultsA total of 160 patients were included, with a mean age of 29.19 years. Of these, 98 were male and 62 female, with a mean BMI of 23.5. The mean follow-up period was 31.7 months. The average ROM was 137.2°, the mean pain level was 0.8, and the average Lysholm score was 95.1. The complication rate was 11%, with 5% requiring reoperation. The graft failure rate was 1.3%. A graft diameter <8mm was associated with females with Fisher's exact test of p<.0001. In the other parameters, no statistically significant differences were found between patients with grafts <8mm and those with grafts ≥8mm.

ConclusionsThis study demonstrates that tape reinforcement in ACL reconstruction is a safe procedure, offering excellent clinical and functional outcomes with low reinterventions and graft failure rates.

El objetivo primario es evaluar los resultados clínicos y funcionales del refuerzo con cinta en las reconstrucciones del ligamento cruzado anterior (LCA), registrando las complicaciones, así como la tasa de reintervenciones y de fracaso del injerto del LCA.

Materiales y métodosAnálisis retrospectivo de reconstrucciones del LCA con autoinjerto de isquiotibiales (IQT) a los que se les asoció un refuerzo con cinta de alta resistencia. Incluimos pacientes en los que obtuvimos un injerto de IQT <8mm o ≥8mm de mala calidad. Se registró edad, sexo, índice de masa corporal (IMC) y actividad previa. Se realizó una evaluación clínica y funcional donde se registró el rango de movilidad posoperatoria (ROM), el dolor y la escala funcional de Lysholm. Se analizaron la tasa de complicaciones, la tasa de fallo del injerto y la tasa de reintervenciones.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 160 pacientes con una edad media de 29,19 años. De estos, 98 eran varones y 62 mujeres, y el IMC medio fue de 23,5. El seguimiento medio fue de 31,7 meses. El ROM medio fue de 137,2°, el dolor medio fue de 0,8 y la puntuación media en la escala de Lysholm fue de 95,1. Detectamos una tasa de complicaciones del 11%, de los cuales hubo que reintervenir al 5%. La tasa de fallo del injerto fue del 1,3%. Se asoció la obtención de una plastia <8mm al sexo femenino con una p<0,0001 con el test exacto de Fischer. En los demás parámetros, no encontramos diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre aquellos pacientes que habían recibido un injerto <8mm y aquellos con injertos ≥8mm.

ConclusionesEl presente estudio muestra que el uso de un refuerzo en la reconstrucción del LCA es un procedimiento seguro, que ofrece excelentes resultados clínicos y funcionales y una baja tasa de reintervenciones y de fallo del injerto.

Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction is one of the most frequently performed orthopaedic surgical procedures worldwide.1,2 Despite its high success rates, residual laxity and graft failure continue to pose a challenge for surgeons.3–5

It has been observed that one of the factors most predisposing to graft rupture is graft diameter, with lower failure rates observed in grafts 8mm or larger in diameter.6–9 While some studies10,11 allow for the prediction of graft diameter before surgery, these do not guarantee complete graft harvesting or predict graft quality. Furthermore, the success of ACL surgery has been shown to depend on the graft's ability to withstand appropriate loads during rehabilitation and subsequent sports activity. During the first year after reconstruction, that is, during early maturation, grafts are particularly vulnerable to re-injury because graft strength is reduced by 30–50%.12,13 Therefore, surgical methods that increase graft strength and protect the graft during the early stages of integration/ligamentisation are of great interest.

Recently, the use of a suture tape (an ultra-high molecular weight braided polyethylene material) as reinforcement for ACL reconstruction has been described.14,15 Its purpose is to protect the graft from excessive loads during the ligamentisation process. In short, the high-strength tape acts like a seatbelt, protecting the graft and providing biomechanical support during the proliferative, maturation, and healing phases.14,15 To date, suture tape reinforcement has shown favourable results in several primary ligament repairs.16–21 However, when adding a surgical procedure, we must not forget the potential complications. Few studies have analysed the outcomes of using suture tape reinforcement in ACL reconstructions.22–24

The primary objective of this study was therefore to evaluate the clinical and functional outcomes of high-strength suture tape reinforcement in ACL reconstruction. Secondary objectives included describing postoperative complications, as well as the reoperation rate and ACL graft failure rate.

Material and methodThis was a retrospective study of patients who underwent arthroscopic ACL reconstruction with high-strength suture tape reinforcement between January 2020 and December 2020 at our institution. All patients were operated on and supervised by three surgeons with specialised knee training. The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards recognised by the Declaration of Helsinki and Resolution 008430 of 1993 and was approved by the Institution's Ethics Committee (Internal code CE042309).

Patients included were those in whom a hamstring tendon graft (HTG) with a diameter <8mm was obtained during surgery, or those in whom, despite having a diameter ≥8mm, the graft was considered to be of poor quality. Patients who were skeletally immature, underwent revision anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction surgery, and had primary ACL reconstructions using allografts or autografts other than HTG were excluded from the study. Cases in which an HTG with a diameter ≥8mm was obtained and not considered to be of poor quality were also excluded. Patients who underwent concomitant posterior cruciate ligament surgery, collateral ligament surgery, or osteotomies were also excluded.

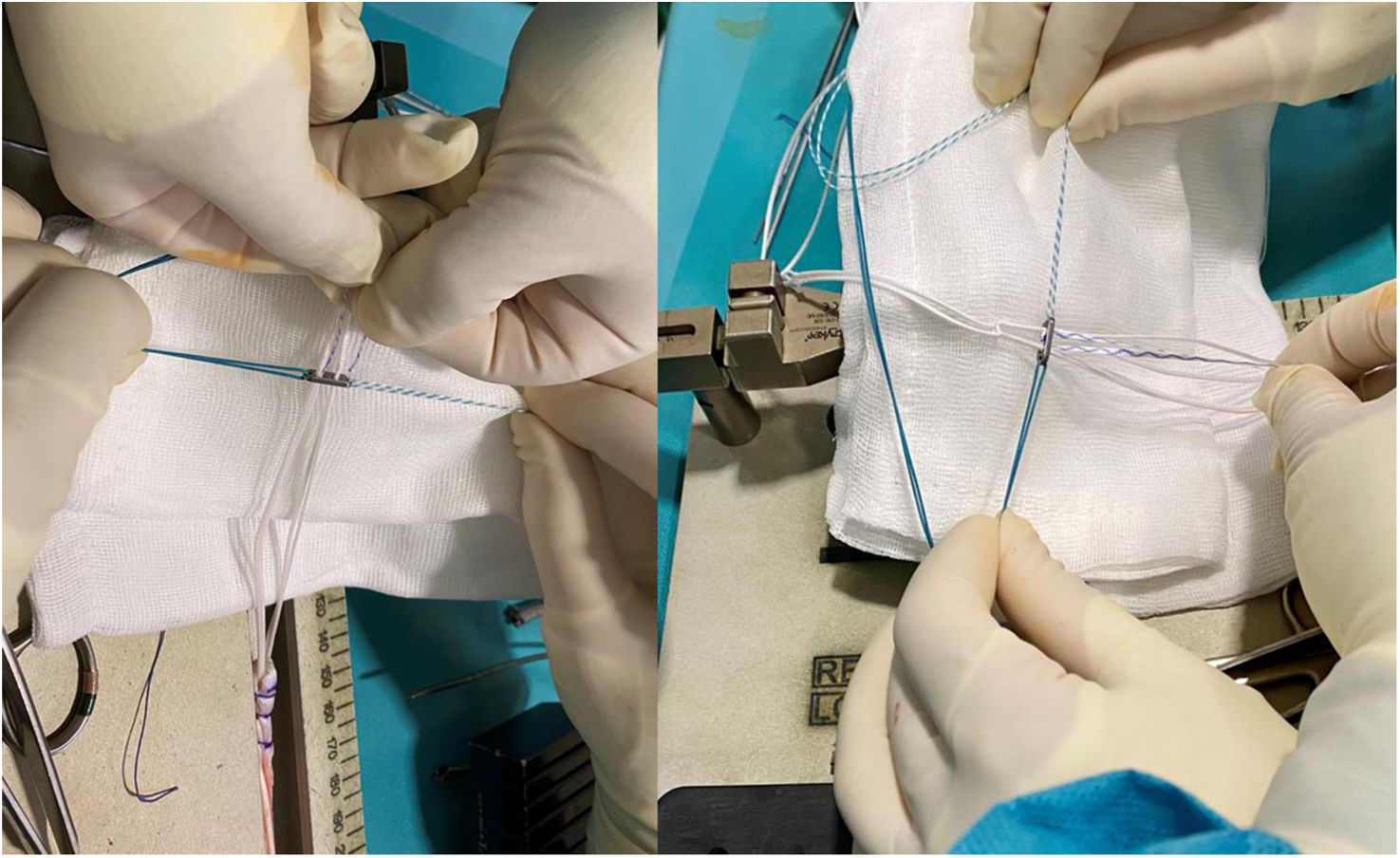

Surgical techniqueThe procedure was performed under spinal anaesthesia in all cases. Antibiotic prophylaxis with 2g of cefazolin was administered. The patient was placed in the supine position, and a tourniquet was induced at 300mmHg. The first step was the harvesting of the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons. These grafts were reinforced with XBraid TT® suture tape (Stryker), which was passed through the Procinch® femoral button (Stryker), creating a double XBraid TT® augmentation (Stryker) (Fig. 1).

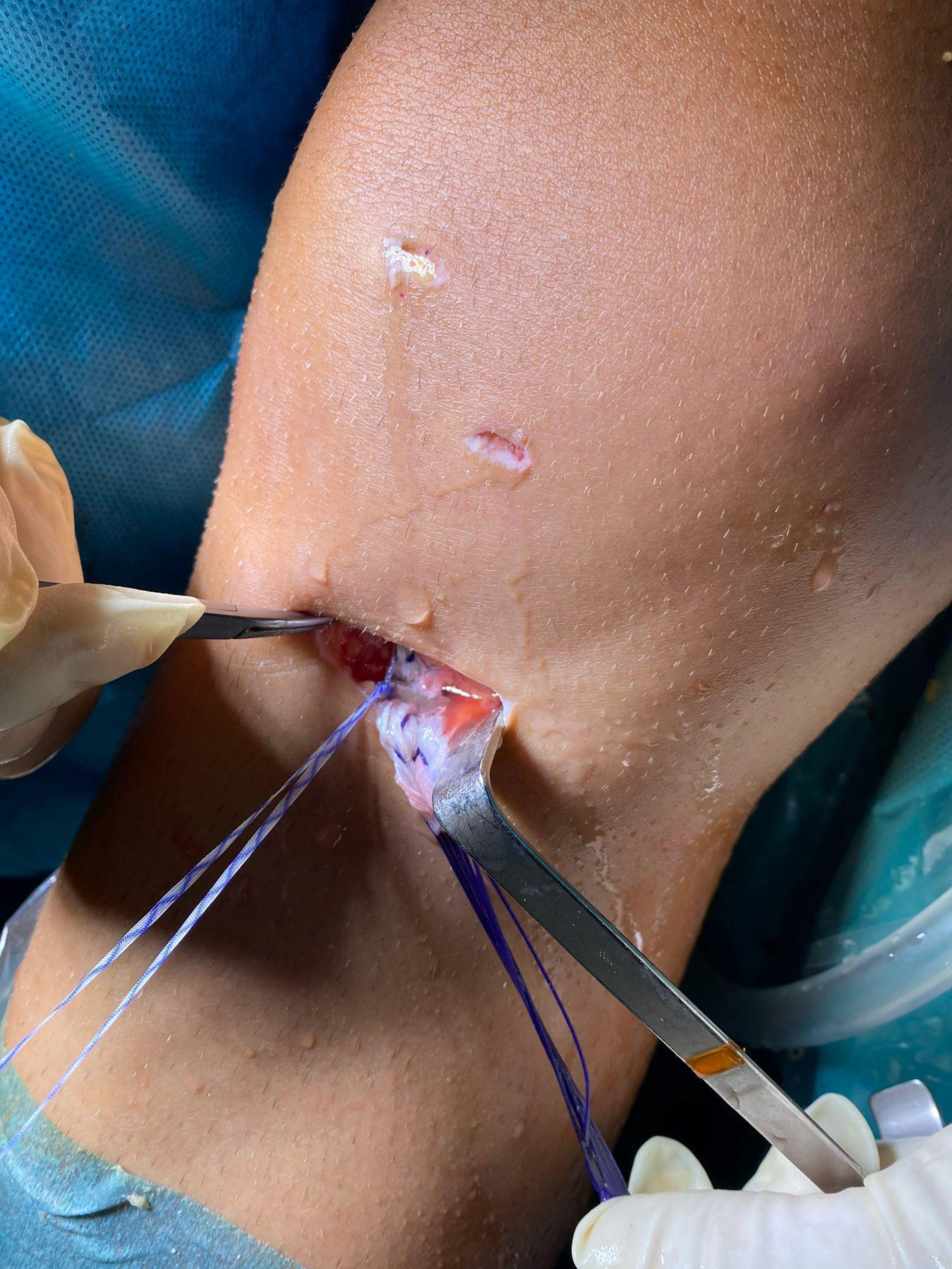

To prevent infection, this graft was placed in saline solution with vancomycin (500mg/100mL of physiological saline). Diagnostic arthroscopy was performed through standard portals. The footprint of the ACL remnant was identified. An anteromedial accessory portal was created. The ACL was reconstructed using an anatomical technique. On the femoral side, a ProCinch® adjustable suspension device (Stryker) was used. On the tibial side, the ACL graft was fixed with a Biosteon® interference screw (Stryker) (Fig. 2) and a staple, with one of the high-strength sutures passed outside the staple (Fig. 3), acting as a post and tied over it (Fig. 4).

Patient medical records were reviewed individually to obtain demographic data such as age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and previous activity level. Injuries associated with the ACL rupture, such as meniscal tears, posterior root tears, or chondral lesions, were also analysed.

Clinical evaluation was performed during successive in-person visits at 1, 3, 6, months and 1 year. A final telephone follow-up was conducted at 2 years. Postoperative range of motion and pain were recorded using the visual analogue scale (VAS). The Lysholm25 scale was used to determine postoperative function. The score ranges from 0 (high disability) to 100 (low disability). Based on the questionnaire score, the functional score was categorised as follows: Poor (score less than 65), Fair (65–83), Good (84–90), and Excellent (scores greater than 90).

Immediate or short-term postoperative complications were recorded and categorised as follows: synovitis or aseptic effusion, infection, neurovascular injury, presence of cyclops lesion, and stiffness, defined as an inability to flex the knee beyond 60° at 6 weeks. We also studied the short-term reintervention rate and the graft failure rate. ACL reconstruction failure was defined as graft rupture diagnosed by magnetic resonance imaging and/or the need for a revision graft procedure. At the end of the follow-up period, the return-to-previous-activity rate for our patients was recorded.

Knowing that the failure rate is higher in the subgroup of patients with grafts <8mm, we wanted to perform a comparative analysis between patients with grafts <8mm and those with diameters ≥8mm.

Finally, knowing that the addition of a lateral extra-articular procedure could have a protective effect on grafts <8mm, we also created a comparative table between patients who underwent a modified lateral extra-articular tenodesis and those who did not.

Statistical analysisFor statistical analysis, IBM® SPSS® Statistics version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) was used. Qualitative or categorical variables were expressed as counts or percentages of the different categories. The relationship between these qualitative variables was studied using contingency tables, which were analysed using Fisher's exact test (2×2 tables) or Pearson's chi-squared test (remaining contingency tables). Quantitative variables were expressed with the mean as the measure of central tendency and the standard deviation as the measure of dispersion. The normality of these variables was determined using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Student's t-test was used to compare the means of normally distributed variables across the different categories of qualitative variables. For variables without a normal distribution, the Mann–Whitney U test was used for hypothesis testing.

All statistical comparisons were two-tailed, with a p-value <.05 considered statistically significant.

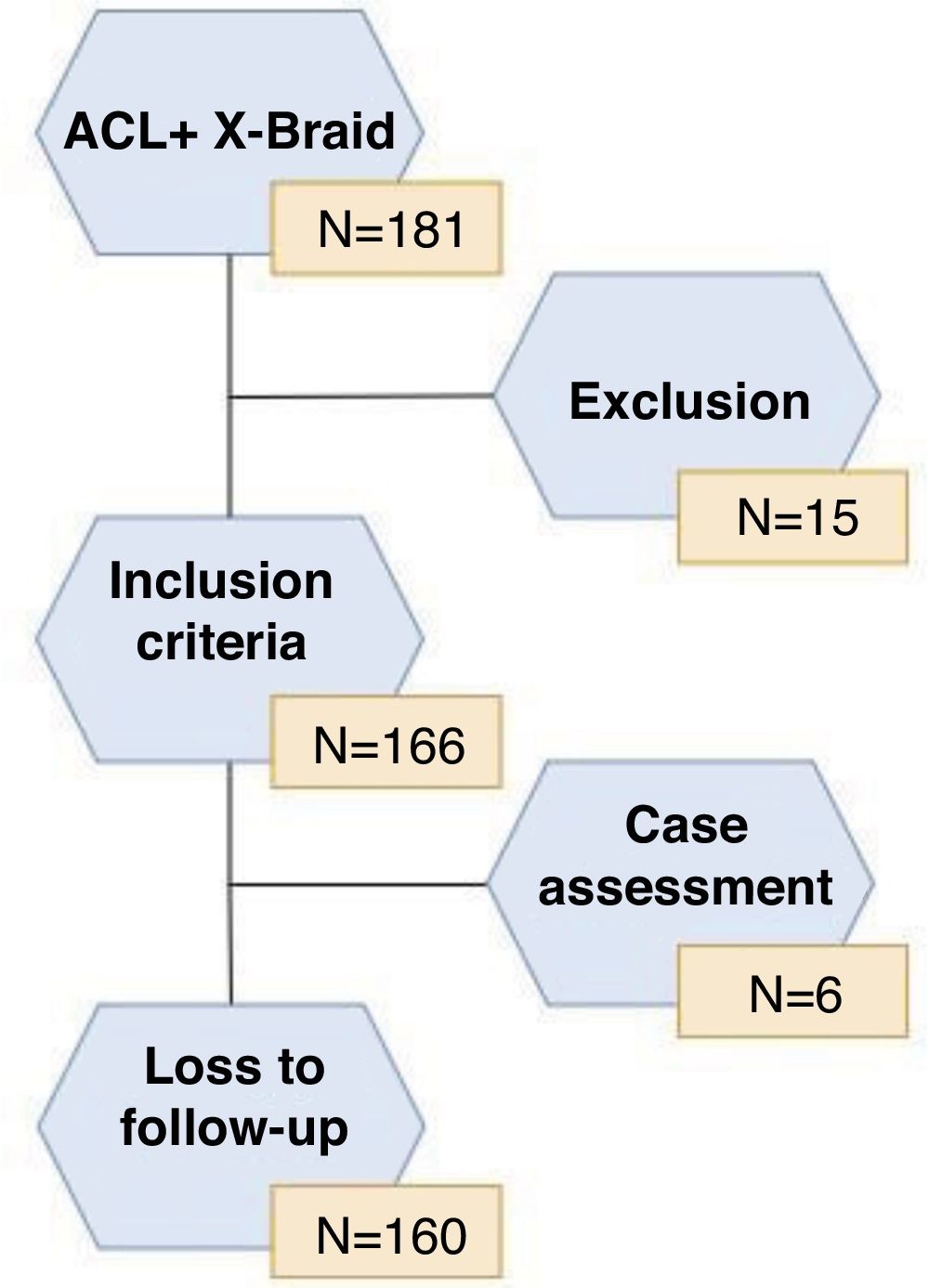

ResultsA total of 181 patients underwent ACL reconstruction surgery with IQT autograft combined with independent high-strength reinforcing tape. Of these, 15 patients were excluded: 8 cases due to ACL revision surgery, 5 cases in which IQT allograft was used, one case in which concomitant posterior cruciate ligament surgery was performed, and one case in which associated medial collateral ligament reconstruction was performed. The minimum follow-up was 24 months, with a mean of 31.7±3.7 months (range: 24–37 months). Of the 166 patients who met the inclusion criteria for the study, 6 were lost to follow-up, leaving a total of 160 patients for final analysis (Fig. 5).

The mean age was 29.19±11.45 years (range: 15–63 years), 98 (61.3%) were male and 62 (38.8%) were female, and the mean BMI was 23.5±2.8 (range: 18.1–33.6). 91.9% of our patients were active in sports prior to their ACL rupture.

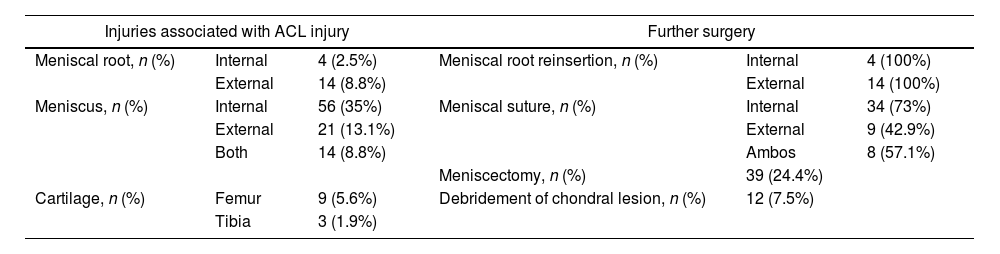

During the surgical procedure, an ACL rupture was confirmed in all patients. The associated intraoperative findings, as well as any additional surgeries performed at the time of the procedure, are summarised in Table 1.

Intraoperative findings associated with ACL injury and additional procedures performed during.

| Injuries associated with ACL injury | Further surgery | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meniscal root, n (%) | Internal | 4 (2.5%) | Meniscal root reinsertion, n (%) | Internal | 4 (100%) |

| External | 14 (8.8%) | External | 14 (100%) | ||

| Meniscus, n (%) | Internal | 56 (35%) | Meniscal suture, n (%) | Internal | 34 (73%) |

| External | 21 (13.1%) | External | 9 (42.9%) | ||

| Both | 14 (8.8%) | Ambos | 8 (57.1%) | ||

| Meniscectomy, n (%) | 39 (24.4%) | ||||

| Cartilage, n (%) | Femur | 9 (5.6%) | Debridement of chondral lesion, n (%) | 12 (7.5%) | |

| Tibia | 3 (1.9%) | ||||

ACL: anterior cruciate ligament.

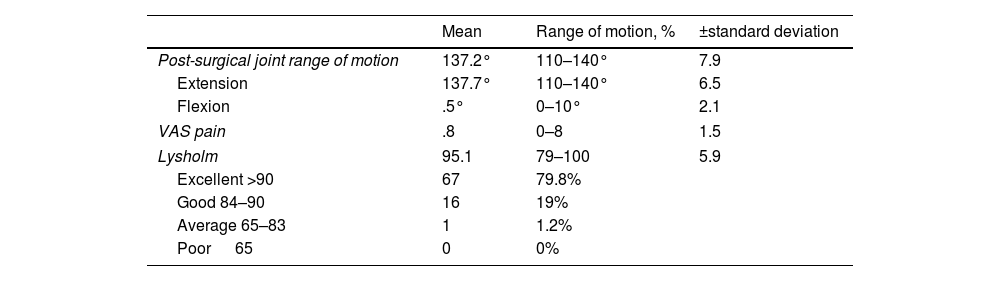

The results of the clinical and functional evaluation are summarised in Table 2.

Clinical and functional evaluation of the patients analysed, where we observe the post-surgical range of motion. Pain was assessed using the visual analogue scale (VAS) and the Lysholm functional knee scale.25

| Mean | Range of motion, % | ±standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-surgical joint range of motion | 137.2° | 110–140° | 7.9 |

| Extension | 137.7° | 110–140° | 6.5 |

| Flexion | .5° | 0–10° | 2.1 |

| VAS pain | .8 | 0–8 | 1.5 |

| Lysholm | 95.1 | 79–100 | 5.9 |

| Excellent >90 | 67 | 79.8% | |

| Good 84–90 | 16 | 19% | |

| Average 65–83 | 1 | 1.2% | |

| Poor 65 | 0 | 0% | |

We observed a postoperative complication rate of 11% (18 patients), including 5 aseptic effusions requiring arthrocentesis, without any further associated procedures; no infections or neurovascular injuries; and 8 cases of postoperative stiffness. Of these, 3 required reoperation for arthroscopic arthrolysis, while the remaining 5 achieved adequate range of motion through mobilisation under anaesthesia alone. Two patients presented with a cyclops lesion resulting in 10° knee flexion contracture, one case of pain related to the tibial fixation staple, and two cases (1.3%) of graft failure at 20 and 26 months postoperatively. The reintervention rate was 5% (8 cases): 3 due to postoperative stiffness (6 weeks after the primary surgery), 2 cases due to cyclops injury, one due to staple-related discomfort, and 2 cases due to graft failure. The return-to-previous-activity rate was 92.5%, with most of our patients being recreational athletes.

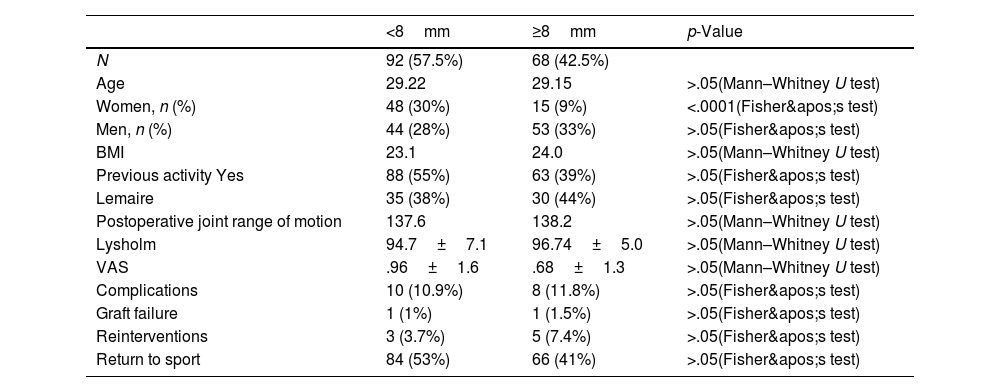

The grafts obtained from HTG had a mean diameter of 7.7±.6mm (range: 6.5–10mm). Ninety-three patients (58.1%) received a graft <8mm, and 67 patients (41.8%) received a graft ≥8mm. Obtaining a graft <8mm was associated with female sex (p<.0001 using Fisher's exact test). In the other parameters, we did not find statistically significant differences between the two groups (Table 3).

Comparison of results in patients with an IQT graft diameter <8mm and a diameter ≥8mm.

| <8mm | ≥8mm | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 92 (57.5%) | 68 (42.5%) | |

| Age | 29.22 | 29.15 | >.05(Mann–Whitney U test) |

| Women, n (%) | 48 (30%) | 15 (9%) | <.0001(Fisher's test) |

| Men, n (%) | 44 (28%) | 53 (33%) | >.05(Fisher's test) |

| BMI | 23.1 | 24.0 | >.05(Mann–Whitney U test) |

| Previous activity Yes | 88 (55%) | 63 (39%) | >.05(Fisher's test) |

| Lemaire | 35 (38%) | 30 (44%) | >.05(Fisher's test) |

| Postoperative joint range of motion | 137.6 | 138.2 | >.05(Mann–Whitney U test) |

| Lysholm | 94.7±7.1 | 96.74±5.0 | >.05(Mann–Whitney U test) |

| VAS | .96±1.6 | .68±1.3 | >.05(Mann–Whitney U test) |

| Complications | 10 (10.9%) | 8 (11.8%) | >.05(Fisher's test) |

| Graft failure | 1 (1%) | 1 (1.5%) | >.05(Fisher's test) |

| Reinterventions | 3 (3.7%) | 5 (7.4%) | >.05(Fisher's test) |

| Return to sport | 84 (53%) | 66 (41%) | >.05(Fisher's test) |

BMI: body mass index; HS: hamstrings; VAS: visual analogue scale for pain.

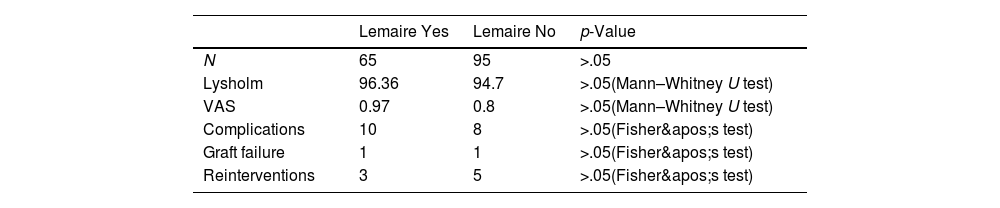

A modified lateral extra-articular tenodesis was performed in 65 patients (40.6%). No statistically significant differences were found between those patients who underwent lateral tenodesis and those who did not (Table 4).

Comparison of results in patients who underwent a Lemaire graft and those who did not.

| Lemaire Yes | Lemaire No | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 65 | 95 | >.05 |

| Lysholm | 96.36 | 94.7 | >.05(Mann–Whitney U test) |

| VAS | 0.97 | 0.8 | >.05(Mann–Whitney U test) |

| Complications | 10 | 8 | >.05(Fisher's test) |

| Graft failure | 1 | 1 | >.05(Fisher's test) |

| Reinterventions | 3 | 5 | >.05(Fisher's test) |

VAS: visual analogue scale of pain.

Our study demonstrates a significant functional improvement after ACL reconstruction combined with suture reinforcement. The mean pain score on the VAS scale was .8±1.5; only 4 patients had a score greater than 5. One patient possibly had post-lateral meniscectomy syndrome, another probably had arthrofibrosis in the immediate postoperative period, and the other two had a subsequent tear of the medial meniscus upon returning to their usual sport.

The overall complication rate was 11% (18 patients), a rate that may seem high, but considering that the range described by various authors varies between 4% and 17.5%,8,27–29 it falls within the expected parameters.

We observed only 5 aseptic effusions (2.8%), which required arthrocentesis to improve their clinical presentation. The use of reinforcement tapes became popular in the 1980s, but they were soon discontinued because they led to high failure rates and the development of chronic synovitis or aseptic knee effusion. This was mainly due to the materials used, such as Dacron®, Gore-Tex®, or Proplast®, which were highly reactive with synovial tissue.18,19 Today, the reinforcement tape is made of ultra-high molecular weight braided polyethylene/polyester, which improves tissue integration and protects the graft during the ligamentisation process.20 This has apparently reduced the prevalence of chronic synovitis to virtually zero (0.2%).17,30 However, some authors still warn against the use of these reinforcement tapes, finding high rates of chronic synovitis, ranging from 20% to 31%.31,32 Ekhtiari et al.33 stated that arthrofibrosis is recognised as the most frequent complication in ACL reconstruction, with rates ranging from 4% to 38% according to different sources. In our study, arthrofibrosis was indeed the most frequent complication, occurring in 8 patients (5%), and in 3 of these cases, arthroscopic arthrolysis was necessary.

Despite the use of modern techniques for ACL reconstruction, a high graft failure rate persists, ranging from 5% to 10%, with 50% of failures occurring in the first year and almost 75% within the first two years.34 In our study, only two cases (1.3%) of graft failure were observed at 20 and 26 months postoperatively. Both cases involved direct trauma while participating in their previous sport, after having experienced good stability. Recent studies have identified certain subpopulations with a re-rupture rate that can reach 23%.5 The groups at highest risk include: individuals under 20 years of age returning to pivoting sports, grafts with a diameter <8mm, and patients with a tibial slope greater than 12°.8 In their meta-analysis Samuelsen et al.4 reported that the ACL failure rate using quadriceps tendon grafts is approximately 2.84%, but this rate rises to 7% when the diameter is less than 8mm.9 In our study, the graft failure rate with a diameter <8mm was 1%, with no statistically significant differences observed compared to diameters ≥8mm.

Techniques have been described that appear to decrease failure rates in patients in whom quadriceps tendon grafts with diameters <8mm were obtained, such as augmentation with contralateral quadriceps tendons or allografts; using a new graft such as bone-patellar tendon-bone or quadriceps; or adding anterolateral ligament reconstruction or lateral extra-articular tenodesis. However, it has been observed that not all of these options yield good results: augmented grafts with contralateral HS grafts have higher failure rates than small-diameter HS grafts (13% vs. 3%), and hybrid grafts (auto- and allograft) appear to have higher failure rates than smaller autografts without allograft reinforcement (30% vs. 5%). Furthermore, the use of a new graft can increase donor-site morbidity with a consequent decrease in strength and a possible increased risk of contralateral ACL rupture.35 Recent studies have shown that the presence of a lateral extra-articular procedure could be an alternative to minimise the possibility of failure in patients with an HTG diameter <8mm.26 In our study, we found no statistically significant differences between those patients in whom we added lateral extra-articular reinforcement and those in whom we did not. Another alternative would be the possibility of braiding the graft, as described by Samitier et al.36 or tripling the HTG as described by several authors,37,38 but we consider tibial fixation in HTG systems a major weakness in the construct,39 and that is why we prioritise a double tibial fixation with a 6mm staple and the interference screw, which does not allow us to triple the graft to increase the diameter, preferring to increase the graft with a reinforcement, as explained in this article.

At the end of the follow-up period, the return-to-previous-activity rate was 91.9%, which is similar to rates reported in other studies, ranging from 80% to 100%.24 Bodendorfer et al.,27 also observed that in patients who received reinforcement in conjunction with the reconstruction, the return to sport was significantly faster (p<.05).

We believe that discovering surgical methods that are effective in increasing the strength of the graft and protecting it during the early stages of integration/ligamentisation is fundamental to improving patient outcomes after ACL reconstruction.

Before comparing our results with other studies, we should clarify the difference between augmentation and reinforcement with high-strength tape: augmentation refers to the technique of creating a graft with a larger diameter, while reinforcement describes the technique of strengthening a graft without necessarily increasing its diameter.29

Several biomechanical studies have shown a potential advantage of using high-strength tape as reinforcement in ACL reconstruction, observing less graft elongation under cyclic loading and less postoperative knee laxity, as well as an increase in the ultimate load required for failure.18,40 Clinically, several retrospective studies have been published comparing the outcomes of using reinforcement in ACL reconstruction with the use of HTG, yielding excellent results with few complications.27–29 Parkes et al.28 conducted a 1:2 matched cohort study, examining 36 patients with reinforcement and 72 without reinforcement, with a minimum follow-up of 2 years. The graft failure rate in the reinforcement suture group was 3%, requiring reoperation in 14% (5 patients) of that group: 2 for a medial meniscus tear, one for a cyclops lesion, and 2 cases of arthrofibrosis. No statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups in the complication rate, clinical outcomes, graft failure rate, or need for reoperation. They only observed a statistically significant improvement in the Tegner activity scale. Bodendorfer et al.27 analysed a 1:1 cohort comparing 30 patients with reinforcement tape versus 30 patients without this reinforcement. They observed a graft failure rate of 6.7% (2 patients) in the reinforcement group, the same as in the control group, and a reintervention rate of 13.3% in the reinforcement group (2 arthrofibrosis (6.7%) and 2 graft failure) compared to 16.7% in the control group, with no statistically significant differences. However, they noted that the group using reinforcement tape achieved a higher percentage of better functional outcomes, and less pain, as well as an earlier return to sport at the same level.

Finally, in their study Kitchen et al.29 compared 40 patients who received a reinforcing suture with 40 patients who did not, with a minimum follow-up of 2 years. They observed a statistically significant improvement in the Tegner activity scale only in the group with reinforcement. In the reinforcement group, the graft failure rate was 5% (2 patients) with a reintervention rate of 12.5%. In this study, only 69.2% of patients returned to their previous sporting activity. As in our analysis, they performed a sub-analysis between patients in whom the graft was <8mm versus ≥8mm, without demonstrating any statistically significant difference. In our opinion, the main conclusion of all these studies is that there are no “red flags” for the use of high-strength suture tape as reinforcement in ACL reconstructions, as it has not been shown to increase the complication rate in ACL reconstructions.27–29 Furthermore, it appears that this device may be a useful tool for improving outcomes and reducing the high graft failure rates, but larger clinical studies and randomised controlled trials are needed to confirm that the use of this reinforcement provides an advantage and improves outcomes compared to traditional ACL reconstruction, thus justifying the additional cost of the implant.41 We should not consider our results without acknowledging the limitations of our study. The study design and sample size limit us from performing a more rigorous statistical analysis. Furthermore, when analysing the postoperative record, residual laxity and the Lachman and anterior drawer tests were not recorded in the medical records. However, our study also has strengths. All patients underwent surgery performed by the same surgical team, with no heterogeneity in graft type, surgical technique, management of meniscal and cartilage lesions, or postoperative rehabilitation plan. Finally, the sample size is larger than in other studies analysing this type of technique.

ConclusionsThis study demonstrates that the use of high-strength tape reinforcement in ACL reconstruction is a safe procedure that offers excellent clinical and functional results and a low rate of reoperations and graft failure.

Level of evidenceLevel of evidence IV.

Ethical considerationsThe study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards recognised by the Declaration of Helsinki and resolution 008430 of 1993 and has the approval of the Research Ethics Committee of the Cemtro Clinic with internal code CE042309. Verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Conflict of interestsOn behalf of all the authors of this article, the main author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.