The occurrence of a difficult airway during intubation is a critical event in anaesthesia. Despite the usefulness of clinical predictors, difficult intubation frequently arises unexpectedly. The aim of this study was to determine the utility of airway ultrasound in detecting these patients.

Materials and methodsThis was a case-control study. The patients in the case group were identified from the registry of patients with reports of difficult laryngoscopy (Cormack III and IV). The controls were selected from among patients classed as Cormack I who underwent surgery under general anaesthesia. Fifty patients (25 cases and 25 controls) participated in the study. All patients underwent ultrasound to obtain 3 measurements: distance from the skin to the hyoid bone, distance from the skin to the epiglottis, and distance from the skin to the vocal cords.

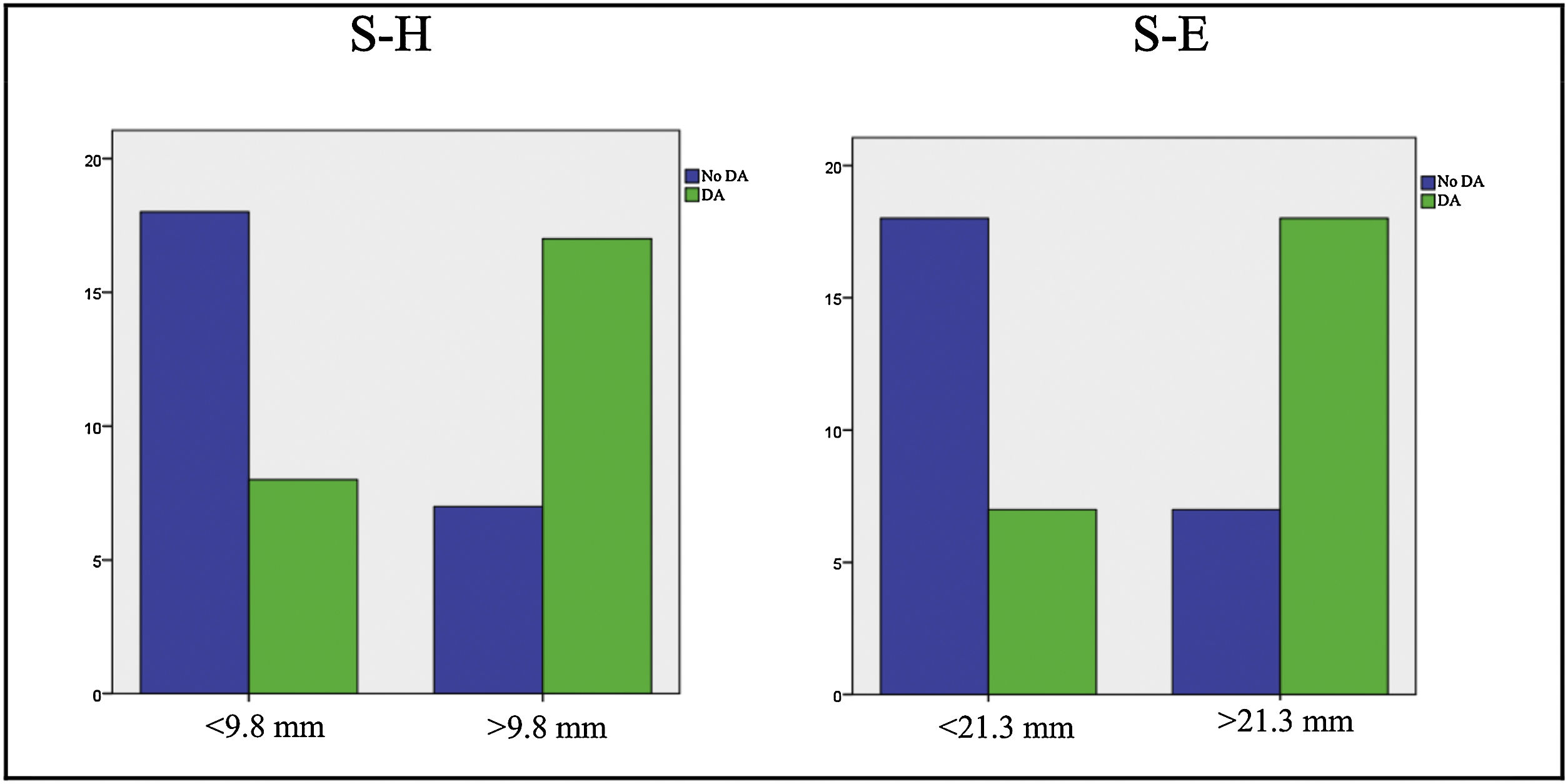

ResultsA skin-to-hyoid bone distance greater than 9.8 mm (50% of the sample) generated an odds ratio of 5.46 (p = 0.005); a skin-to-epiglottis distance greater than 21.3 mm (50% of the sample) generated an odds ratio of 6.62 (p = 0.002). There was no significant difference in the skin-to-vocal cords distance.

ConclusionsUltrasound has proven to be a useful tool for predicting difficult laryngoscopy. Despite the low sensitivity of clinical predictors, they appear to improve the detection of patients with difficult laryngoscopy when integrated into predictive models alongside ultrasound values.

La incidencia de la vía aérea difícil durante la intubación es un episodio crítico en anestesia. A pesar de la utilidad de los indicadores predictivos clínicos, dicho episodio surge a menudo de manera inesperada. El objetivo de este estudio fue determinar la utilidad de la ecografía de la vía aérea para detectar a estos pacientes.

Materiales y métodosEstudio de casos y controles. Los pacientes del grupo de casos fueron identificados a partir del registro de pacientes con informes de laringoscopia difícil (Cormack III y IV). Los controles fueron seleccionados entre los pacientes sometidos a cirugía con anestesia general identificados como Cormack I. Cincuenta pacientes (25 casos y 25 controles) participaron en el estudio. Se realizó ecografía a todos los pacientes para determinar tres medidas: distancia de la piel al hueso hioides, distancia de la piel a la epiglotis y distancia de la piel a las cuerdas vocales.

ResultadosTener una distancia de la piel al hueso hioides superior a 9,8 mm (50% de percentil de la muestra) generó un odds ratio de 5,46 (p = 0,005); Tener una distancia de la piel a la epiglotis superior a 21,3 mm (50% de percentil de la muestra) generó un odds ratio de 6,62 (p = 0,002). No existió diferencia significativa en la medida de la distancia de la piel a las cuerdas vocales.

ConclusionesLa ecografía ha demostrado ser una herramienta útil para la predicción de la laringoscopia difícil. A pesar de la baja sensibilidad de los indicadores predictivos clínicos, estos parecen ayudar a mejorar la detección de los pacientes con laringoscopia difícil cuando se integran en modelos predictivos junto con los valores ecográficos.

Airway management is standard practice during anaesthesia. However, when difficulty arises, it can lead to severe morbidity because unexpected difficult intubation is a potentially life-threatening event. Difficult or failed intubation is the leading cause of death and brain injury in airway management.1 One of the main factors contributing to difficulty in intubation is difficult direct laryngoscopy (DL), defined as a grade III or IV on the Cormack-Lehane (CL) scale.2 Certain predictors are used in clinical practice to identify patients at risk of DL. Despite their utility, they have limited sensitivity when used individually and are merely predictors, so the risk of unexpected DL persists.3,4 The significance of this problem drives the ongoing search for evidence to help anaesthesiologists identify these patients and manage intubation difficulties with the highest safety guarantees.

Ultrasound is a tool that has recently been used to predict the occurrence of DL.5–10 Several measurements have been described, including skin-to-epiglottis distance, skin-to-hyoid distance, skin-to-vocal cords distance, tongue thickness, and thyromental distance. A meta-analysis has shown that the distance from the skin to the epiglottis, hyoid and vocal cords measured by ultrasound is greater in patients with DL and provides a cut-off point to predict its occurrence.8

This study could help us understand the utility of ultrasound in the identification of patients with DL. Identifying ultrasound values related to the onset of DL could help minimize risks and reduce morbidity and mortality associated with this event when it occurs unexpectedly. Our hypothesis was that airway anatomy measured by ultrasound can be used as a cut-off point to determine the risk of experiencing difficulty in orotracheal intubation. The primary aim was to determine the association between ultrasound measurements in the anterior cervical region and the risk of encountering difficulty in orotracheal intubation. The secondary aims were to determine the association of DL with clinical predictors and anthropometric variables, and statistically describe ultrasound measurements and clinical predictors in both groups.

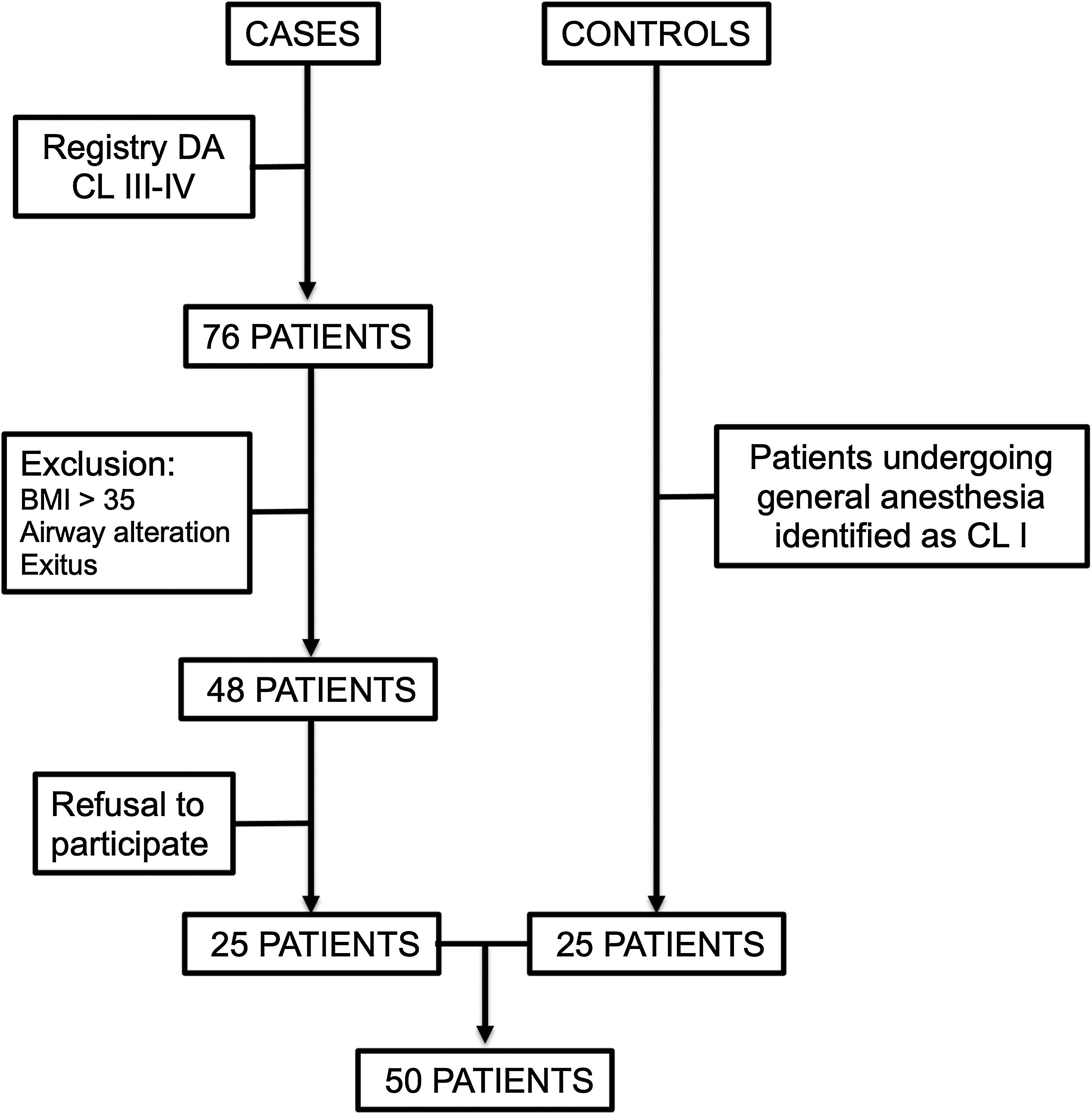

MethodsThis is a case-control study conducted at the Valencia General University Hospital Consortium. The study was designed according to the STROBE guidelines, and was approved in July 2022 by the Ethics Committee of the Valencia General University Hospital Consortium, with acceptance reference code KOT-VAD 57/2022. Cases were identified from the Valencia General Hospital Consortium register of patients with reported DL. The inclusion criteria were: Cormack-Lehane grade (CL) III and IV (determined in all cases by an anaesthesiologist with more than 5 years of experience) in the case group; CL I and elective surgery under general anaesthesia in the control group; and age over 18 years in both groups. Exclusion criteria were BMI < 18 or >35; tracheostomy; anatomical changes after surgery or radiation to the neck; and refusal to participate in the study. All patients included in the study were Caucasian.

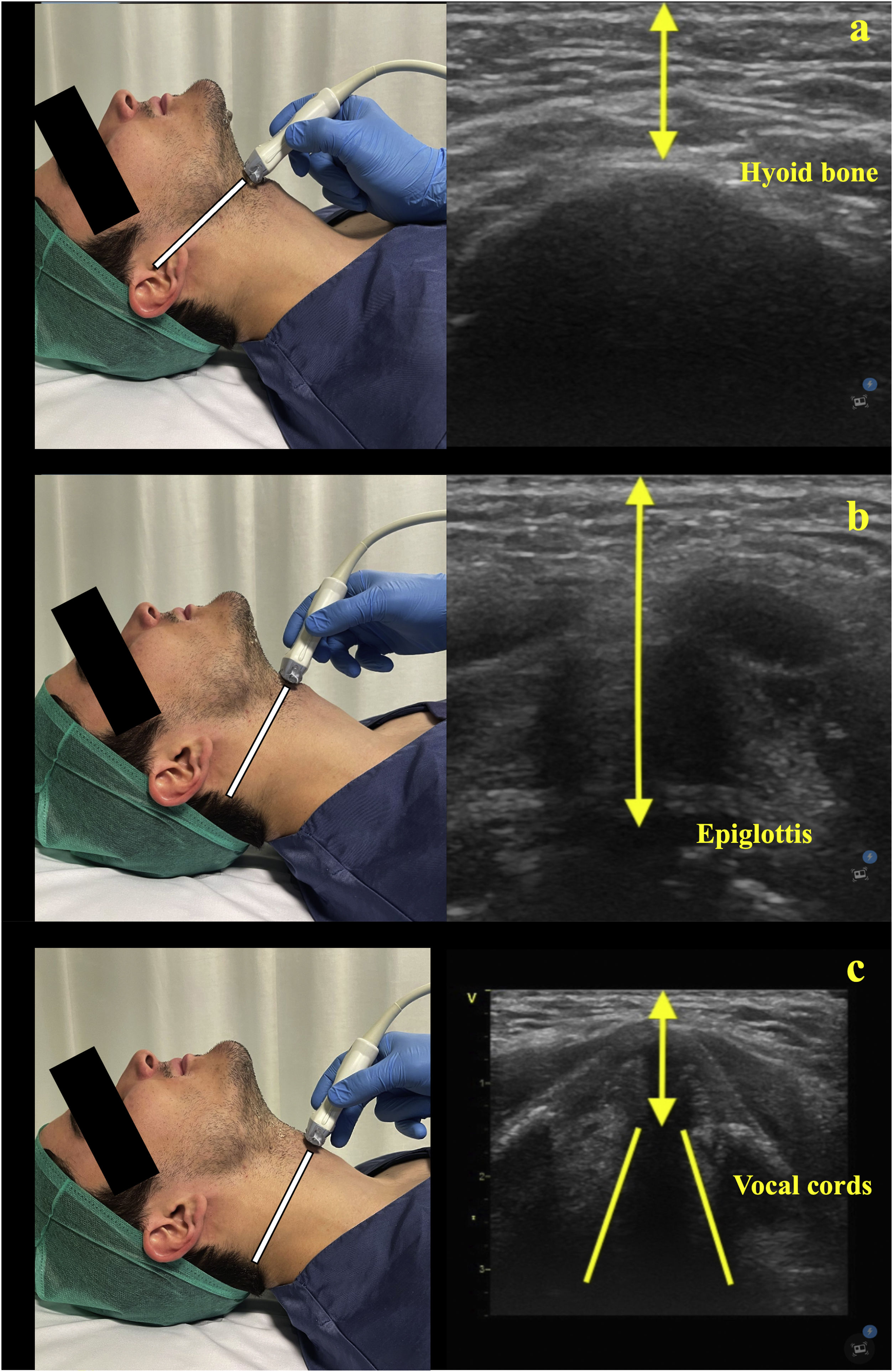

The patient recruitment period was from 1 July to 15 September 2022; there was a 1:1 ratio of cases to controls. All patients underwent ultrasound examination to determine 3 measurements (Fig. 1): skin-to-hyoid, skin-to-epiglottis, and skin-to-vocal cord. Measurements were performed in all patients in the supine position with the neck in hyperextension, and were performed by the same researchers (PK and LR) in all cases. The examination was performed using an ultrasound system (General Electric Healthcare Vivid T8®). A high-frequency linear probe (7−12 MHz) placed in the axial plane was used to explore the airway (Supplementary Video). The case patients underwent ultrasound measurement during a medical consultation. The control patients underwent ultrasound measurement in the PACU after being identified as CL I. We also collected descriptive variables (age, gender, BMI) and clinical predictors (Mallampati grade, thyromental distance and bite test).

The sample size was calculated using OpenEpi (version 3). The hypothetical proportion of cases and controls with exposure was extracted from the study by Pinto et al.6 For a confidence level (1-alpha) of 95% and an estimated 10% losses, the required sample size for cases and controls would be 48 patients.

Descriptive statistics of the variables were obtained. Continuous variables were reported as mean and standard deviation (SD), categorical variables were reported as number and percentage. Group comparisons of continuous variables were made using the Student’s t-test. The chi-square test was used for categorical variables with the Bonferroni correction for intergroup comparisons.

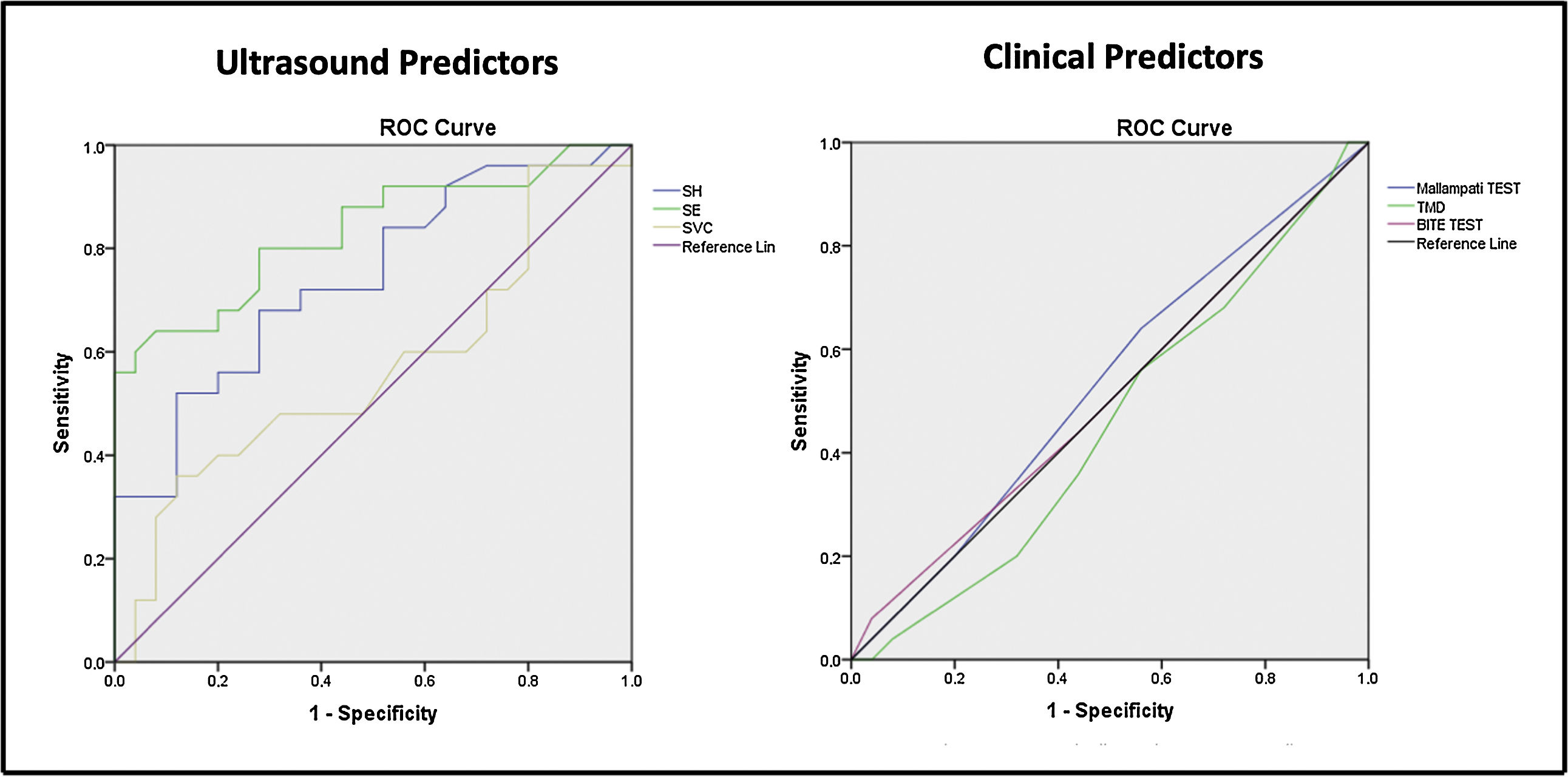

The odds ratio (OR) was used to quantify the strength of the association between ultrasound distance and DL. The area under the curve (AUC) and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to evaluate the accuracy of the tests (clinical predictors and ultrasound distance tests). Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v 26. (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). A p-value <0.05 was considered significant.

ResultsFifty patients (25 cases and 25 controls) participated in the study. Seventy-six patients were assigned to the case group, but 28 of these met one of more of the exclusion criteria. The remaining 48 were contacted by telephone and 25 agreed to participate in the study. The other 25 controls were selected from among patients identified as CL grade I who underwent surgery under general anaesthesia but were otherwise similar to cases (Fig. 2). Of the patients who participated in the study, 22 were men (44%) and 28 were women (56%), with ages ranging from 25 to 86 years and a mean body mass index of 27.40. There were no significant differences between groups.

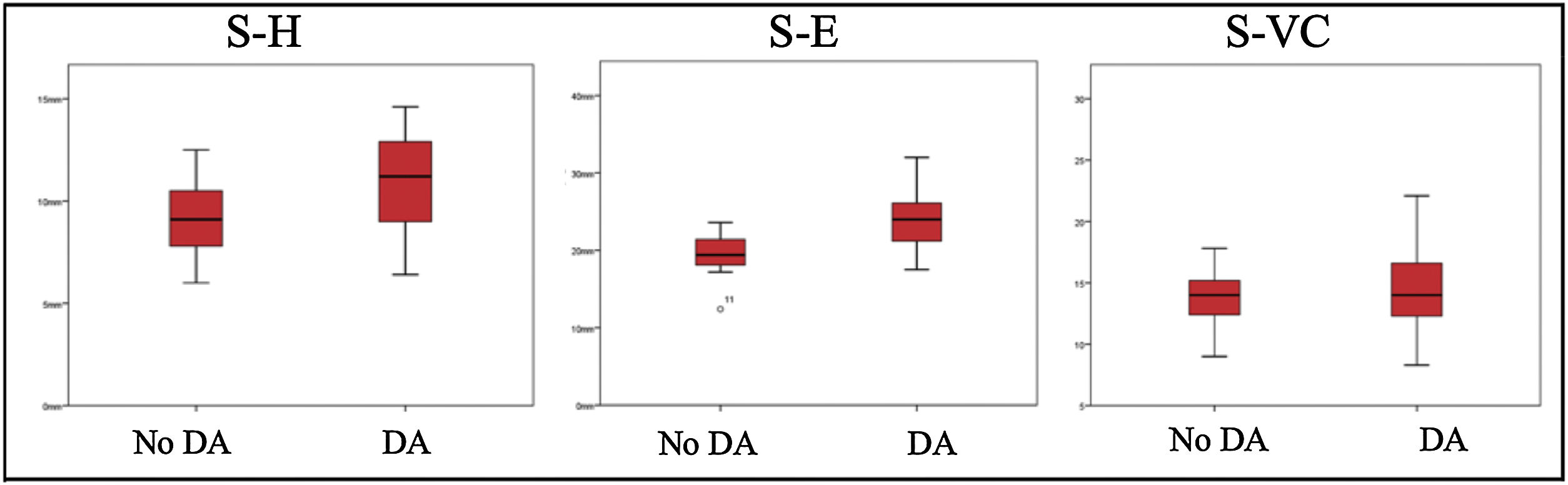

Ultrasound measurements of skin-to-hyoid, skin-to-epiglottis, and skin-to-vocal cords were obtained from all patients in both groups. Differences in the measurements obtained between the groups are shown in Fig. 3.

The mean skin-to-hyoid distance measured by ultrasound in patients with DL was 10.9 (±2.1) mm vs 9 (±1.8) mm in patients without DL. This difference is significant (p = 0.002), with the mean absolute value of this difference being 1.9 (±0.5) mm.

A skin-to-hyoid distance of 9.9 mm (50% of the sample) would be the cut-off point for point-of-care ultrasound of the airway. Any distance greater than this predicts a DL with a sensitivity of 68% and a specificity of 72%; in this test, the area under the curve was 0.742 (Fig. 4).

A skin-to-hyoid distance of more than 9.8 mm gave an odds ratio of 5.46 (p = 0.005) (Fig. 5).

The mean skin-to-epiglottis distance measured by ultrasound in patients with DL was 24 (±3.9) mm vs 19.5 (±2.4) mm in patients without DL; this difference was significant (p = 0.002).

Considering the cut-off point, the mean difference between patients with and without DL is approximately 4.5 (±0.9) mm.

The cut-off point for point-of-care ultrasound of the airway was a skin-to-epiglottis distance of 20.95 mm. Any value above this had a sensitivity of 80% and a specificity of 72% to predict DL. In this test, the area under the curve was 0.832 (Fig. 4).

A skin-to-epiglottis distance greater than 21.3 mm (50% of the sample) gave an odds ratio of 6.62 (p = 0.002) (Fig. 5). However, there was no significant difference between skin-to-vocal cords distance.

The descriptive values, ultrasound measurements, and clinical predictors of DL in both groups (cases and controls) are shown in Table 1.

Comparative variables.

| Cormack Lehane classification | I (controls) | III–IV (cases) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptive variables | Age (years), m | 52.08 | 61.8 | 0.026 |

| Male/Female, n | 10/15 | 12/13 | 0.578 | |

| BMI, m | 26.41 | 28.39 | 0.9 | |

| Ultrasound distances, m (±SD) | S-H (mm) | 9.05 ± 1.87 | 10.97 ± 2.16 | 0.002 |

| S-E (mm) | 19.52 ± 2.40 | 24.06 ± 3.93 | 0.002 | |

| S-VC (mm) | 17.69 ± 19.95 | 14.69 ± 3.06 | 0.462 | |

| Clinical predictors | Mallampati (I–II/III–IV), n | (20/5) | (20/5) | 0.819 |

| TMD (cm), m(±SD) | 7.8 ± 0.8 | 8.02 ± 1 | 0.556 | |

| Bite Test (1/2/3), n | (14/10/1) | (14/9/2) | 0.355 | |

There were no significant differences between groups in the results of standard predictive tests. There were no differences between groups in the bite test (p = 0.355), and no differences in the distribution of frequencies for the Mallampati test, showing that there is no important or relevant association between the Mallampati test and DL. Thyromental distance <6 cm was not observed in any patient; the overall mean distance was 7.95 (±0.3) cm (case group 7.8 [±0.8] cm vs control group 8.02 [±1] cm [p = 0.556]).

DiscussionIn our study, the distance from the skin to various airway structures was measured using ultrasound and compared between individuals with and without DL. We observed that the most sensitive and specific test for predicting DL was the skin-to-epiglottis distance, followed by the skin-to-hyoid distance. The area under the curve in both tests (0.832 and 0.742, respectively) were very similar to those described in the meta-analysis by Carsetti et al.8 (0.87 and 0.77, respectively). Consistent with these findings, the measurements that have been described as having the highest predictive power in most studies are the skin-to-epiglottis distance, the skin-hyoid distance, and the hyomental distance ratio.8–12 However, the predictive power of the skin-to-vocal cords distance is less clear. Carsetti et al.8 report a high predictive power (AUC 0.78), but in our study we observed no differences between groups, a finding that is consistent with the results of some studies that found no correlation between skin-to-vocal cords distance and DL.13,14 This may due to the difficulty involved in measuring the skin-to-vocal cords distance, or differences between the two types of patients in this area.

Despite this, the findings of our study show that ultrasound exploration of the anterior laryngeal region could help predict DL. It is a simple tool that provides an immediate diagnosis at the point of care. Most of the standard point-of-care tests used to predict DL have been shown to have a low sensitivity.3,4,10 In our study, we found that none of the clinical predictors used in routine practice effectively predict DL, a finding echoed in most studies. In a meta-analysis, Roth et al.3 studied the correlation between 7 clinical predictors (3 of which were also assessed in our study) and DL. Of the 3 predictors assessed in our study, they found that the upper lip bite test has a higher sensitivity (0.67) compared to the Mallampati and thyromental distance tests (0.4 and 0.37, respectively). Despite their low individual predictive power, when used in combination they can increase the sensitivity for detecting patients with DL. Nevertheless, although a combination of standard predictive tests are used to identify these patients, unexpected difficult intubation due to DL is not uncommon. The incidence of patients with DL is 10% and causes 25% of anaesthesia related deaths.4 Early detection of these patients is essential to correctly prepare for this eventuality and provide assistance with the highest safety guarantee.

Our findings highlight the benefit of describing other tests to predict DL. In the case of ultrasound, no single measurement has sufficient power to predict difficult laryngoscopy. However, there is evidence that combining several ultrasound metrics with clinical parameters can create an accurate tool for detecting DL.15–17 We did not perform any parametric combination models; however, it is likely that as more studies are conducted in this area, airway sonoanatomy will be integrated into predictive models of DL.

An important aspect to mention is that patients with a difficult airway should be differentiated from those with CL grades III and IV. These two circumstances coincide in most cases; however, better glottic view is not necessarily associated with easy endotracheal tube insertion.18 Additionally, other factors such as the anaesthesiologist's experience, materials used during endotracheal intubation, or the operating environment can influence the occurrence of a difficult airway. In fact, according to some authors,19 the difficulty in managing the airway depends not only on anatomical factors (as described in this study) but also on a series of contextual factors that determine this difficulty.

This study has are several limitations that need to be mentioned. It is a single-centre study with a small sample size that was performed in Caucasian patients. Therefore, it would be interesting to promote future prospective multicentre studies with a larger number of cases and controls to study the validity of other potential predictors of difficult laryngoscopy. Additionally, it would be advisable to create a combination model that includes clinical predictors and ultrasound measurements to determine the utility of an integrated predictive model.

In conclusion, ultrasound has proven to be a useful tool for predicting DL. Isolated clinical predictors have limited utility and only improve identification of DL when added to predictive models that include ultrasound measurements.