The urinary biomarker [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] enables the prediction of postoperative acute kidney injury (PO-AKI). Our study aimed to assess the incidence of PO-AKI in high-risk patients undergoing major abdominal surgery and to evaluate the impact of implementing KDIGO renal optimization measures in those with renal stress identified by [TIMP-2]×[IGFBP7].

Materials and methodsThis was a prospective study including 182 patients who underwent major abdominal surgery. Perioperative data, [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] levels, and the implementation of KDIGO renal protection strategies in the ICU were collected. Predictors of PO-AKI were identified through multivariate analysis.

ResultsThe overall incidence of PO-AKI was 25.3%, reaching 42.7% in ICU patients. [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] showed moderate predictive ability (AUROC = 0.74), with a PO-AKI incidence of 47.5% in patients with elevated levels. Despite the implementation of KDIGO measures in the ICU, the incidence of PO-AKI in patients with elevated [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] was 65.6%. In multivariate analysis, the main predictors of PO-AKI were elevated [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] (OR = 6.3; 95% CI: 2.6–15.6; p < 0.001), male sex (OR = 6.1; 95% CI: 1.9–19.6; p = 0.002), and ICU admission (OR = 4.5; 95% CI: 1.5–13.6; p = 0.009).

ConclusionsPO-AKI is common after major abdominal surgery, particularly in ICU patients. The [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] biomarker allows for early identification of at-risk patients, although the implementation of KDIGO measures in the ICU did not significantly reduce its incidence.

El biomarcador urinario [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] permite predecir la lesión renal aguda postoperatoria (LRA-PO). Nuestro estudio tuvo como objetivos evaluar la incidencia de LRA-PO en pacientes de riesgo renal sometidos a cirugía mayor abdominal e investigar el impacto de la implementación de medidas de optimización renal KDIGO en aquellos con estrés renal identificado por [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7].

Materiales y métodosEstudio prospectivo en 182 pacientes sometidos a cirugía mayor abdominal. Se recogieron datos perioperatorios, niveles de [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] y la aplicación de estrategias de protección renal KDIGO en la UCI. Se identificaron predictores de LRA-PO mediante análisis multivariante.

ResultadosLa incidencia global de LRA-PO fue del 25,3%, alcanzando el 42,7% en los ingresados en UCI. [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] mostró una capacidad predictiva moderada (AUROC = 0,74), con una incidencia de LRA-PO del 47,5% en pacientes con niveles elevados. A pesar de la implementación de medidas KDIGO en la UCI, la incidencia de LRA-PO en pacientes con [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] elevado fue del 65,6%. En el análisis multivariante, los principales predictores de LRA-PO fueron: un [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] elevado (OR = 6,3; IC 95%: 2,6–15,6; p < 0,001), el sexo masculino (OR = 6,1; IC95%:1,9–19,6; p = 0,002) y el ingreso en UCI (OR = 4,5; IC95%:1,5–13,6; p = 0,009).

ConclusionesLa LRA-PO es frecuente tras cirugía mayor abdominal, especialmente en pacientes ingresados en UCI. El biomarcador [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] permite la identificación temprana de pacientes en riesgo, aunque la implementación de medidas KDIGO en la UCI no logró reducir significativamente su incidencia.

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is characterized by an increase in plasma creatinine and/or a decrease in urine output. These functional criteria have been updated following the introduction of the RIFLE scale in 2004 and the AKIN (Acute Kidney Injury Network) criteria in 2007. In 2012, the KDIGO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) criteria unified previous definitions and established the gold standard for identifying and stratifying AKI.1–3

AKI is a common complication after major surgery, especially in patients with risk factors,1–4 and is associated with increased mortality, chronic kidney failure and high care costs.1,2,5

The postoperative incidence reported in the literature varies from 13% to 50%, with a higher incidence being reported in urological surgery and in procedures requiring extracorporeal circulation.1–8 These differences in incidence rates may be due to the fact that few studies simultaneously evaluate creatinine and diuresis in the diagnosis of AKI.1,2,2–8

Opinions still vary on the best perioperative management of AKI, due in part to the lack of a standard diagnostic strategy.1–3,9 The KDIGO criteria can identify patients with AKI, but cannot detect subclinical AKI.1–3 Functional biomarkers such as creatinine (SCr), urine output, and glomerular filtration rate (GFR) have limited sensitivity and specificity, and can only diagnose AKI at a late stage, when significant loss of GFR has already occurred. This delays intervention and can lead to irreversible damage.1,3,8

The recent discovery and validation of biomarkers of kidney damage in high-risk patients, such as cystatin C, neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL), kidney injury molecule 1 (KIM-1), interleukin 18 (IL-18), and π-glutathione S-transferase (π-GST), has been a significant breakthrough.1,3,7,8,10–12

Two proteins have recently shown promising results: tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase 2 (TIMP2) and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 7 (IGFBP7), marketed under the name NephroCheck® (BioMérieux Spain). The test measures urinary concentrations of TIMP2 and IGFBP7 using sandwich fluorescence immunoassay. These proteins are released by the renal tubule in response to harmful stimuli, and stop the cell cycle in the G1 phase to prevent cell division and senescence, a key mechanism in the pathophysiology of AKI.3,7,10–14 Elevated TIMP2 and IGFBP7 indicates cellular stress in the renal tubule and suggests a high risk of developing AKI without necessarily indicating the presence of structural damage. The AKIRisk® score is derived from the formula [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP-7]/1000, expressed in (ng/ml)2/1000. A cut-off value of 0.3 (ng/ml)2/1000 (positive AKIRisk score) has high sensitivity and acceptable specificity for a high risk of moderate to severe AKI in the next 12 h. In critically ill patients, a score greater than 2 (ng/mL)2/1000 suggests a very high risk of AKI.7,10,13,15 The AKIRisk® score allows clinicians to take prompt action that can potentially prevent irreversible damage and improve prognosis. Several authors consider TIMP-2 and IGFBP-7 to be biomarkers not of kidney damage (such as NGAL and KIM-1) but of stress, since their elevation does not necessarily imply an adverse prognosis if early preventive measures are implemented.

Studies such as PrevAKI (in cardiac surgery)6 and BigPAK (in major abdominal surgery)7 have shown that the use of TIMP2-IGFBP7 combined with preventive strategies from the KDIGO guidelines reduces the incidence of AKI in high-risk patients.6–8,10,16,17 However, these recommendations are still rarely followed in clinical practice.3,10

The primary objective of our study was to determine the overall incidence of AKI in patients at risk of kidney injury undergoing major abdominal surgery. We included patients admitted to the ICU and ward in order to present an accurate picture of standard clinical practice and determine the utility of the AKIRisk® biomarker. In order to reduce the incidence of PO-AKI in patients with kidney stress, we also analysed the impact of implementing KDIGO kidney optimization measures in ICU patients with a positive AKIRisk score.

Our secondary objectives were: to evaluate AKI risk factors associated with the patient and the perioperative period and to analyse morbidity and mortality rates, including the incidence of Major Adverse Kidney Events at 90 days (MAKE90), a composite outcome that includes mortality, need for continuous renal replacement therapy, and permanent deterioration of kidney function, defined more than 25% loss of estimated GFR at 90 days.

We hypothesised that early detection of AKI using the TIMP-2 x IGFBP7 biomarker, together with the application of postoperative kidney protection measures could improve the prognosis of patients undergoing major abdominal surgery.

Materials and methodWe conducted a prospective, observational study in patients with risk factors for kidney injury undergoing major abdominal surgery. The study protocol was approved by our hospital’s research ethics committee (project 2020.117) and informed consent was obtained.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaThe inclusion criteria, identified in the pre-anaesthesia consultation, were:

- a)

Over 18 years.

- b)

Scheduled for major abdominal surgery: open abdominopelvic or laparoscopic general, urological, gynaecological surgery expected to last more than 2 h.

- c)

At least one risk factor for AKI according to the KDIGO guidelines16: age > 65 years, chronic kidney disease (CKD), high blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, cancer, anaemia, chronic cardiopulmonary disease (ischaemic heart disease, atrial fibrillation, congestive heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) or liver disease (cirrhosis).

We excluded patients with CKD stage >3B (eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73 m2), scheduled or previous nephrectomy and transplants, and those who refused to participate in the study.

MethodologyAll consecutive patients recruited from 7 April 2021 to 23 February 2022 were included. Postoperative admission to the ICU was indicated by the anaesthesiologist based on the type of surgery, the patient’s progress in the operating room and their status.

In all patients, a urine sample was obtained from a urinary catheter 4 h after the end of the intervention and sent for NephroCheck® testing. To obtain the sample, the catheter was clamped for 15 min to obtain urine, which was then sent to the central laboratory for analysis. High risk of AKI in the immediate postoperative period (first 72 postoperative hours) was defined as an AKIRisk score > 0.3 (ng/ml)2/1000 (positive AKIRisk score). In ICU patients, the anaesthesiologist in charge was told which had a positive AKIRisk score so that they could implement the kidney optimization measures recommended in the KDIGO guidelines,16,17 consisting of (1) normalising blood volume (assessed by performing the passive leg raising test or administering a mini-bolus of intravenous fluids to assess fluid responsiveness), (2) achieving haemodynamic stability with normotension (MAP ≥ 65 mmHg with vasopressors, if required), (3) withdrawal and avoidance of nephrotoxic agents and (4) strict glycaemic control (between 110−180 mg/dl). Urinary catheters were maintained for the first 72 postoperative hours in patients admitted to the ICU; in most patients admitted to the ward they were removed after running the NephroCheck® test. Urine output was measured every 24 h on the ward by collecting spontaneous urine in a container. Ward patients were managed by surgical teams following the standard surgical protocol; KDIGO recommendations were not systematically implemented.

Diagnosis and classification of AKIPostoperative AKI (PO-AKI) was diagnosed on the basis of baseline (up to 30 days before surgery) and postoperative creatinine values and postoperative diuresis. PO-AKI was stratified according to the KDIGO guidelines (Table 1).8,16

Classification of acute kidney injury according to the KDIGO guidelines.

| Stage | Serum creatinine | Urine output |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.5−1.9 times baseline OR | <0.5 ml/kg/h for 6−12 h |

| ≥0.3 mg/dl (≥26.5mmol/l) increase | ||

| 2 | 2−2.9 times baseline | <0.5 ml/kg/h for ≥12 h |

| 3 | ≥3 times baseline OR | <0.3 ml/kg/h for ≥24 h, OR |

| Increased in serum creatinine to ≥4 mg/dl, (≥353.6 mmol/l) OR | Anuria for ≥12 h | |

| Initiation of renal replacement therapy OR, In patients <18 years, decrease in eGFR to <35 ml/min/1.73 m2 |

We collected demographic, surgical, and kidney function variables in the preoperative and intraoperative periods, and within the first 72 postoperative hours. We also recorded the patient’s AKI stratification and the emergence of complications at 90 days: permanent kidney dysfunction, need for renal replacement therapy, and mortality.

Preoperative variables included risk factors for AKI: age, ASA, sex, high blood pressure (HBP), ischaemic heart disease (IHD), atrial fibrillation (AF), heart failure (HF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), diabetes mellitus (DM), anaemia, and chronic use of nephrotoxic agents (ACE inhibitors/ARBs, NSAIDs and beta-blockers). We also collected baseline kidney function variables: creatinine (SCr), urea and glomerular filtration rate (MDRD).

Intraoperative variables included the type of surgery performed, the type and duration of surgery, the need for urgent surgery, the surgical approach, the anaesthesia used, the presence of haemodynamic instability, the need for vasoactive agents or fluid therapy, diuresis, and the use of nephrotoxic agents.

Postoperative variables included ICU stay, length of hospital stay, need for invasive monitoring, presence of haemodynamic instability, use of vasoactive agents and transfusions, fluids administered, use of nephrotoxic drugs, and postoperative complications (bleeding, infections, or sepsis). We also assessed haematological and kidney function parameters (SCr and MDRD) at admission, and at 24, and 48 h; daily urine output in the first 72 h; AKIRisk (NephroCheck®) score at 4 h postoperatively; and AKI stage and major complications (MAKE90). The SOFA and SAPS III scores were calculated at admission to the ICU.

Statistical analysisWe calculated a sample size of 152 patients to detect a 20% relative reduction in the incidence of PO-AKI (from 37% to 17%), which we considered clinically significant, with a statistical power of 80% and a significance level of 5%.1 The 37% incidence was derived from a retrospective analysis of patients admitted to the ICU after major abdominal surgery in 2019 (prior to the pandemic), using exclusively creatinine measurements for the diagnosis of AKI.

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to confirm the normal distribution of the data. Discrete variables are described as absolute frequency (n, %), continuous variables as mean ± standard deviation, and as median (interquartile range) if they do not follow a normal distribution. Baseline and perioperative characteristics according to the presence of AKI or a positive AKIRisk score were analysed using the Chi-square test and Student's t or Mann-Whitney U tests, depending on the distribution. The capacity of the AKIRisk score to predict AKI was evaluated using the area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUROC). Two multivariate analyses were performed using binary logistic regression to evaluate the association between AKI and a positive AKIRisk score, using the clinical variables with significant differences in the univariate analysis as independent variables. The odds ratio (OR) was calculated for each variable, along with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI) and p-values. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The study data were analysed on SPSS V.20 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

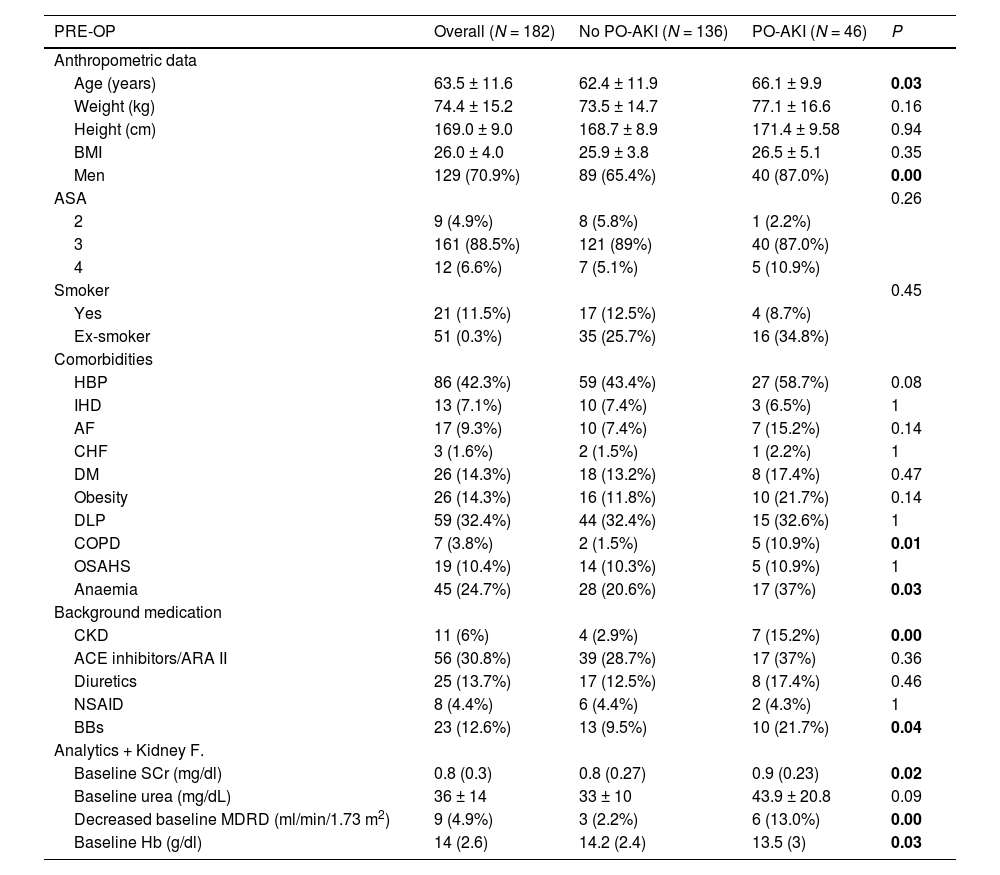

ResultsA total of 182 patients undergoing major abdominal surgery were included, of whom 82 were admitted to the ICU. Preoperative patient characteristics are shown in Tables 2 and A1.

Overall and comparative preoperative data of patients with and without postoperative acute kidney injury (PO-AKI).

| PRE-OP | Overall (N = 182) | No PO-AKI (N = 136) | PO-AKI (N = 46) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anthropometric data | ||||

| Age (years) | 63.5 ± 11.6 | 62.4 ± 11.9 | 66.1 ± 9.9 | 0.03 |

| Weight (kg) | 74.4 ± 15.2 | 73.5 ± 14.7 | 77.1 ± 16.6 | 0.16 |

| Height (cm) | 169.0 ± 9.0 | 168.7 ± 8.9 | 171.4 ± 9.58 | 0.94 |

| BMI | 26.0 ± 4.0 | 25.9 ± 3.8 | 26.5 ± 5.1 | 0.35 |

| Men | 129 (70.9%) | 89 (65.4%) | 40 (87.0%) | 0.00 |

| ASA | 0.26 | |||

| 2 | 9 (4.9%) | 8 (5.8%) | 1 (2.2%) | |

| 3 | 161 (88.5%) | 121 (89%) | 40 (87.0%) | |

| 4 | 12 (6.6%) | 7 (5.1%) | 5 (10.9%) | |

| Smoker | 0.45 | |||

| Yes | 21 (11.5%) | 17 (12.5%) | 4 (8.7%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 51 (0.3%) | 35 (25.7%) | 16 (34.8%) | |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| HBP | 86 (42.3%) | 59 (43.4%) | 27 (58.7%) | 0.08 |

| IHD | 13 (7.1%) | 10 (7.4%) | 3 (6.5%) | 1 |

| AF | 17 (9.3%) | 10 (7.4%) | 7 (15.2%) | 0.14 |

| CHF | 3 (1.6%) | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (2.2%) | 1 |

| DM | 26 (14.3%) | 18 (13.2%) | 8 (17.4%) | 0.47 |

| Obesity | 26 (14.3%) | 16 (11.8%) | 10 (21.7%) | 0.14 |

| DLP | 59 (32.4%) | 44 (32.4%) | 15 (32.6%) | 1 |

| COPD | 7 (3.8%) | 2 (1.5%) | 5 (10.9%) | 0.01 |

| OSAHS | 19 (10.4%) | 14 (10.3%) | 5 (10.9%) | 1 |

| Anaemia | 45 (24.7%) | 28 (20.6%) | 17 (37%) | 0.03 |

| Background medication | ||||

| CKD | 11 (6%) | 4 (2.9%) | 7 (15.2%) | 0.00 |

| ACE inhibitors/ARA II | 56 (30.8%) | 39 (28.7%) | 17 (37%) | 0.36 |

| Diuretics | 25 (13.7%) | 17 (12.5%) | 8 (17.4%) | 0.46 |

| NSAID | 8 (4.4%) | 6 (4.4%) | 2 (4.3%) | 1 |

| BBs | 23 (12.6%) | 13 (9.5%) | 10 (21.7%) | 0.04 |

| Analytics + Kidney F. | ||||

| Baseline SCr (mg/dl) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.27) | 0.9 (0.23) | 0.02 |

| Baseline urea (mg/dL) | 36 ± 14 | 33 ± 10 | 43.9 ± 20.8 | 0.09 |

| Decreased baseline MDRD (ml/min/1.73 m2) | 9 (4.9%) | 3 (2.2%) | 6 (13.0%) | 0.00 |

| Baseline Hb (g/dl) | 14 (2.6) | 14.2 (2.4) | 13.5 (3) | 0.03 |

PRE-OP: preoperative, BMI: body mass index, ASA: (American Society of Anesthesiology), HBP: high blood pressure, IHD: ischaemic heart disease, AF: atrial fibrillation, CHF: congestive heart failure, DM: diabetes mellitus, DLP: dyslipidaemia, COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, OSAHS: sleep apnoea-hypopnoea syndrome, CKD: chronic kidney disease, ACEI: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARI II: angiotensin II receptor antagonists, NSAID: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, BB: beta-blockers, Kidney F: kidney function, SCr: serum creatinine, MDRD: decreased Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study = < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2, Hb: haemoglobin.

Bold means P <0.05.

The incidence of PO-AKI was 25.3%: 43 cases were stage 1, two were stage 2, and one was stage 3. Of these, 10.9% presented oliguric AKI.

Patients with a higher incidence of PO-AKI were older, predominantly male, and presented preoperative comorbidities: CKD, anaemia, COPD, and treatment with beta-blockers (Table 2).

Major adverse kidney events (MAKE90)The incidence of MAKE90 was 1.1% (2/182), with 1 death and 1 patient requiring renal replacement therapy. No sequelae were observed over the 90-month follow-up.

The only patient requiring renal replacement therapy (KDIGO 3) presented septic shock requiring readmission to the ICU 8 days after a cephalic pancreatectomy.

The patient, who died 16 days postoperatively, suffered severe malnutrition and infectious and metabolic complications following gastric bypass reversal surgery, and was readmitted to the ICU due to cardiac arrest.

Intraoperative characteristics and PO-AKIShown in Tables 3 and A2.

Overall and comparative intraoperative data of patients with and without postoperative acute kidney injury (PO-AKI).

| INTRA-OP | Overall (n = 182) | NO PO-AKI (n = 136) | PO-AKI (n = 46) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department | 0.29 | |||

| General surgery | 114 (62.4%) | 82 (60.3%) | 32 (69.6%) | |

| Gynaecological surgery | 5 (2.7%) | 5 (3.7%) | 0 (0 %) | |

| Urological surgery | 63 (34.6%) | 49 (36.0%) | 14 (30.4%) | |

| Type of surgery | 0.00 | |||

| Prostatectomy | 47 (25.8%) | 42 (30.9%) | 5 (10.9%) | |

| Colectomy | 32 (17.6%) | 27 (19.9%) | 5 (10.9%) | |

| Hepatectomy | 20 (11.0%) | 16 (11.8%) | 4 (8.7%) | |

| Pancreatectomy | 26 (14.3%) | 14 (10.3%) | 12 (26.1%) | |

| HIPEC | 9 (4.9%) | 5 (3.7%) | 4 (8.7%) | |

| Other | 74 (40.7%) | 46 (33.8%) | 28 (60.9%) | |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 298 (175) | 277 (142) | 379 (238) | 0.00 |

| Approach | 0.00 | |||

| Open | 50 (27.5%) | 26 (19.1%) | 24 (52.2%) | |

| Laparoscopic | 86 (47.2%) | 69 (50.7%) | 17 (37.0%) | |

| Robotic | 46 (25.3%) | 41 (30.1%) | 5 (10.9%) | |

| Urgent | 7 (3.8%) | 6 (4.4%) | 1 (2.2%) | 0.68 |

| Anaesthesia | ||||

| GA | 152 (83.5%) | 120 (88.2%) | 32 (69.6%) | 0.00 |

| Mixed (GA + LRA) | 30 (16.5%) | 16 (11.8%) | 14 (30.4%) | |

| Invasive INTRA-OP monitoring | 164 (90.1%) | 120 (88.2%) | 44 (95.7%) | 0.25 |

| INTRA-OP HD instability | 74 (40.7%) | 49 (36%) | 25 (54.3%) | 0.03 |

| INTRA- OP vasoactive agents | 84 (46.2%) | 56 (41.2%) | 28 (60.9%) | 0.02 |

| INTRA- OP noradrenaline | 9 (4.9%) | 7 (5.1%) | 2 (4.3%) | 1 |

| INTRA- OP adrenaline | 2 (1.1%) | 2 (1.5%) | 0 | 1 |

| INTRA- OP dobutamine | 3 (1.6%) | 2 (1.5%) | 1 (2.2%) | 1 |

| INTRA- OP ephedrine | 63 (34.6%) | 41 (30.1%) | 22 (47.8%) | 0.03 |

| INTRA- OP phenylephrine | 31 (17%) | 19 (14%) | 12 (26.1%) | 0.07 |

| INTRA-OP diuresis (ml/kg/h) | 1 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (0) | 0.46 |

| INTRA-OP fluid management (ml/kg/h) | 4 (3) | 5 (3) | 4 (2) | 0.00 |

| INTRA-OP crystalloids (ml/kg/h) | 4.4 ± 2.5 | 4.8 ± 2.7 | 3.5 ± 1.5 | 0.00 |

| INTRA- OP transfusion | 14 (7.7%) | 8 (5.8%) | 6 (13 %) | 0.12 |

| INTRA- OP nephrotoxic drugs | 130 (71.4%) | 105 (77.2%) | 25 (54.3%) | 0.00 |

| INTRA- OP NSAIDs | 115 (63.1%) | 95 (69.9%) | 20 (43.5%) | 0.00 |

| INTRA- OP diuretics | 31 (17%) | 21 (15.4%) | 10 (21.7%) | 0.36 |

INTRA-OP: intraoperative, HIPEC: HyperthermicIntraPeritonealChemotherapy, GA: general anaesthesia, LRA: locoregional anaesthesia.

Bold means P <0.05.

The incidence of PO-AKI was higher in patients undergoing longer surgeries, who underwent general anaesthesia as the only technique, required invasive monitoring, open surgery, presented episodes of hemodynamic instability, needed vasoactive agents and more restrictive fluid therapy, and presented lower intraoperative diuresis.

Pancreatectomy and cystectomy were associated with the highest incidence of PO-AKI.

Postoperative characteristics and PO-AKIShown in Tables 4 and A3.

Overall and comparative postoperative data of patients with and without postoperative acute kidney injury (PO-AKI).

| POST-OP | Overall (N = 182) | NO PO-AKI (N = 136) | PO-AKI (N = 46) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-op admission to ICU | 82 (45.1%) | 47 (34.6%) | 35 (76.1%) | 0.00 |

| POST-OP invasive monitoring | 80 (44%) | 46 (33.8%) | 34 (73.9%) | 0.00 |

| SOFA on admission to ICU | 1 (3) | 0 (2) | 1 (3) | 0.11 |

| SAPS III on admission to ICU | 35.7 ± 10.7 | 35.4 ± 11.4 | 36 ± 9.8 | 0.8 |

| POST-OP fluid management (ml/kg/h) | ||||

| 24 h | 1.1 (0.8) | 1.1 (0.6) | 1.4 (1) | 0.02 |

| 48 h | 0.9 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.7) | 0.09 |

| 72 h | 0.7 (0.4) | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.8 (0.5) | 0.08 |

| POST-OP HD instability | 16 (8.8%) | 7 (5.1%) | 9 (19.6%) | 0.00 |

| POST- OP vasoactive agents | 13 (7.1%) | 7 (5.1%) | 6 (13 %) | 0.09 |

| POST- OP transfusion | 21 (11.5%) | 9 (6.6%) | 12 (26.1%) | 0.00 |

| POST- OP diuretics | 0.00 | |||

| Bolus | 55 (30.2%) | 34 (25%) | 21 (45.7%) | |

| CP | 12 (6.6%) | 5 (3.7%) | 7 (15.2%) | |

| POST- OP nephrotoxic drugs | 161 (88.5%) | 126 (92.6%) | 35 (76.1%) | 0.00 |

| POST- OP NSAIDs | 158 (86.8%) | 124 (91.2%) | 34 (73.9%) | 0.00 |

| POST- OP complications | 27 (14.8%) | 13 (9.5%) | 14 (30.4%) | 0.00 |

| POST- OP bleeding | 19 (10.4%) | 9 (6.6%) | 10 (21.7%) | 0.00 |

| Post-op infection/sepsis | 11 (6%) | 4 (2.9%) | 7 (15.2%) | 0.00 |

| Lab tests, Hb (g/dL) | ||||

| On admission to ICU | 11.8 + 2.1 | 11.9 + 1.9 | 11.7 + 2.3 | 0.63 |

| 24 h | 12 (3) | 12 (2) | 11 (4) | 0.00 |

| 48 h | 11 (3) | 11 (3) | 9 (4) | 0.00 |

| Kidney F. | ||||

| Cr (mg/dl) | ||||

| Admission | 0.9 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.3) | 1.1 (0.4) | 0.00 |

| 24 h | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.3) | 1.2 (0.5) | 0.00 |

| 48 h | 0.9 + 0.3 | 0.7 + 0.2 | 1 + 0.3 | 0.00 |

| Decreased MRDR | ||||

| Admission | 13 (7.1%) | 2 (1.5%) | 11 (23.9%) | 0.00 |

| 24 h | 19 (10.4%) | 4 (2.9%) | 15 (32.6%) | 0.00 |

| 48 h | 11 (6%) | 2 (1.5%) | 9 (19.6%) | 0.02 |

| POST-OP diuresis (ml/kg/h) | ||||

| 24 h | 1.5 (1) | 1.4 (1.1) | 1.6 (1) | 1 |

| 48 h | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.6) | 0.3 |

| 72 h | 1.4 + 0.5 | 1.4 + 0.5 | 1.3 + 0.6 | 0.09 |

| NEPHROCHECK (ng/ml)2/1000) | 0.17 (0.3) | 0.12 (0.23) | 0.4 (0.37) | 0.00 |

| Positive AKIRisk score (>0.3 (ng/ml)2/1000) | 61 (33.5%) | 32 (23.5%) | 29 (63%) | 0.00 |

| POST- OP RRT | 1 (0.5%) | 0 | 1 (2.2%) | 0.25 |

| Oliguric PO-AKI | 5 (2.7%) | 0 | 5 (10.9%) | 0.25 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| SCr 90 d (mg/dl) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.8 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.4) | 0.04 |

| MAKE 90 | ||||

| SCr > 25% baseline | 0 | 0 | ||

| TDE 90 | 0 | 1 (2.2%) | 0.25 | |

| 90-day mortality | 0 | 1 (2.2%) | 0.25 | |

| ICU stay (days) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) | 0.00 |

| Ward stay (days) | 6 (5.2) | 5 (3.7) | 8.5 (10) | 0.00 |

POST-OP: postoperative; ICU: intensive care unit, SOFA: Sequential Organ Failure Assessment, SAPS: Simplified Acute Physiology Score, HD: haemodynamics, CP: continuous perfusion, RRT: renal replacement therapy, PO-AKI: postoperative acute kidney injury, SCr 90 d = serum creatinine at 90 days, MAKE 90: Major Adverse Kidney Events at 90 days.

Bold means P <0.05.

The incidence of PO-AKI was higher in patients admitted to the ICU, with haemodynamic instability, needing vasoactive agents and blood transfer, treated with diuretics, and those with postoperative complications. Length of stay in the ICU and on the ward were greater in these patients.

Positive AKIRisk score and PO-AKI (Fig. 1)Of the 61 patients with a positive AKIRisk score, 47.5% developed PO-AKI compared to 14.0% with a negative AKIRisk score. The overall sensitivity of a positive AKIRisk score was 63%, with a specificity of 76%, a positive predictive value (PPV) of 48% and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 86%.

Incidence of PO-AKI was 65.6% among the 32 patients with a positive AKIRisk score admitted to the ICU. This was significantly higher than the incidence of PO-AKI among patients with a positive AKIRisk score admitted to the ward (27.6%).

Likewise, in patients with a negative AKIRisk score, the incidence of PO-AKI was higher in the ICU (28%), compared to the ward (4.2%). In the ICU, a positive AKIRisk score showed a sensitivity of 60%, specificity of 77%, PPV of 66% and NPV of 72%.

The absolute value of [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] showed a moderate discriminatory capacity for PO-AKI, with an AUROC of 0.74 (95% CI: 0.67−0.82, p < 0.001). Only 3 patients had [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] > 2 (ng/ml)2/1000, indicative of very high risk of AKI; 2 of these developed PO-AKI.

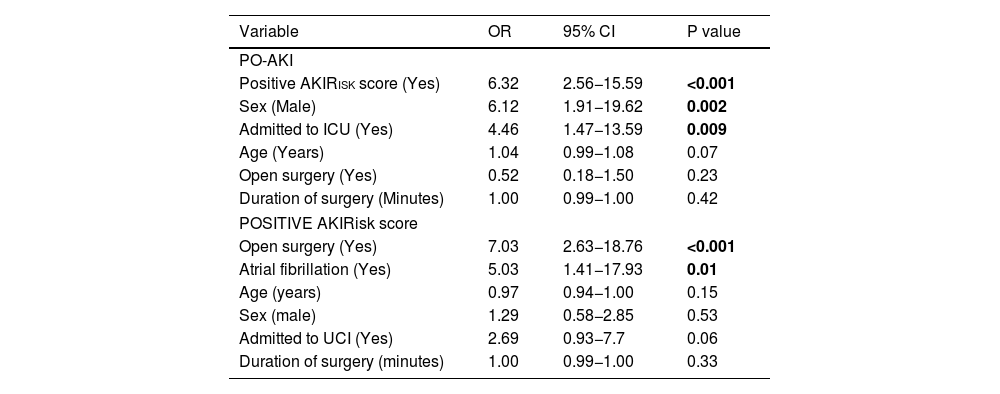

Multivariate analysis of PO-AKIMultivariate analysis identified the following significant predictors of PO-AKI: a positive AKIRisk score, male sex, and ICU admission (Table 5).

Multivariate analysis of factors associated with PO-AKI and positive AKIRisk score in the postoperative period of major abdominal surgery.

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PO-AKI | |||

| Positive AKIRisk score (Yes) | 6.32 | 2.56−15.59 | <0.001 |

| Sex (Male) | 6.12 | 1.91−19.62 | 0.002 |

| Admitted to ICU (Yes) | 4.46 | 1.47−13.59 | 0.009 |

| Age (Years) | 1.04 | 0.99−1.08 | 0.07 |

| Open surgery (Yes) | 0.52 | 0.18−1.50 | 0.23 |

| Duration of surgery (Minutes) | 1.00 | 0.99−1.00 | 0.42 |

| POSITIVE AKIRisk score | |||

| Open surgery (Yes) | 7.03 | 2.63−18.76 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation (Yes) | 5.03 | 1.41−17.93 | 0.01 |

| Age (years) | 0.97 | 0.94−1.00 | 0.15 |

| Sex (male) | 1.29 | 0.58−2.85 | 0.53 |

| Admitted to UCI (Yes) | 2.69 | 0.93−7.7 | 0.06 |

| Duration of surgery (minutes) | 1.00 | 0.99−1.00 | 0.33 |

Bold means P <0.05.

The 82 patients admitted to the ICU presented significant differences in the type of surgery and comorbidities compared to those admitted to the ward (Table A4). They also presented worse physical status (ASA4: 12% vs. 2%), higher prevalence of CKD (11% vs. 0%) HBP (56.1% vs. 40%) and AF (17.1% vs. 3%), and a higher proportion underwent open surgery (54.9% vs. 5%), with longer duration (455 ± 216 vs. 259 ± 90 min), less use of intraoperative crystalloids (4.4 ± 3.4 vs. 5.3 ± 2.1 ml/kg/h), higher volume of blood transfusion (14.6% vs. 2%) and need for vasoactive agents (64.6% vs. 31%).

Factors associated with a positive AKIRisk scoreThe perioperative variables associated with a positive AKIRisk score were: presence of AF, smoking history, and open surgery under general anaesthesia with no locoregional anaesthesia (see Table A5). The highest incidence of a positive AKIRisk score occurred in pancreatectomies and colectomies.

Multivariate analysis identified open surgery and AF as significant predictors of a positive AKIRisk score (Table 5).

DiscussionOur main findings were as follows:

- a

The incidence of PO-AKI in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery was high (25.3%) and significantly higher in those admitted to the ICU (42.7%).

- b

A positive AKIRisk score showed moderate predictive capacity for early detection of PO-AKI, with an AUROC = 0.74, showing that it is a useful risk biomarker.

- c

Despite the implementation of kidney protection measures recommended in the KDIGO guidelines, ICU patients with a positive AKIRisk score had a high incidence of PO-AKI (65.6%). However, these measures could have helped reduce the severity of kidney failure, and suggests that they need to be optimised or supplemented with additional interventions.

The incidence of PO-AKI after abdominal surgery is increasing, probably due to population ageing, comorbidities, and more aggressive surgeries.2,4,8,18 In our study, the overall incidence was 25.3% – in line with the rate reported in the literature – with a low proportion of moderate to severe cases (KDIGO 2-3: 6.5%).

It is difficult to compare our results with other studies due to considerable differences in the populations analysed and the variables measured. The largest study, EPIS-AKI,4 evaluated the incidence, risk factors and outcomes of PO-AKI after major surgery (not just abdominal), without differentiating between patients admitted to the ICU or the ward. Of the 3170 patients included, 571 (29.4%) developed PO-AKI. However, this study does not provide specific data on the incidence of PO-AKI in different types of major abdominal surgery and does not describe specific management strategies.

In our study, the incidence of PO-AKI was almost 4 times higher in patients admitted to the ICU (42.7%) compared to the ward (11%), despite the implementation of measures to optimise kidney function. This is probably due to the fact that many patients admitted to the ICU will have undergone more aggressive surgery and have a higher comorbidity burden. Previous studies, such as BigPAK,7 have shown that the application of KDIGO measures can reduce the incidence of PO-AKI. However, differences between this study and ours in terms of population characteristics, type of surgery, intraoperative management, and postoperative strategies could explain these discrepancies.

Although the low mortality observed in our cohort did not allow us to detect significant differences in major kidney events in patients with PO-AKI (in line with previous studies6,7), kidney function in these patients had normalised within 90 days to levels similar to those observed in patients that did not develop PO-AKI. This suggests that early detection and appropriate management could prevent or delay progression to CKD. However, we should not underestimate the impact of AKI, even at stage 1, as it has been associated with an increased risk of CKD, cardiovascular events, mortality, hospital readmission, and decreased quality of life.19

Risk factors for PO-AKIThe preoperative variables associated with PO-AKI in our study, such as advanced age, male sex, COPD, anaemia, and CKD are the same as those reported elsewhere.2,8,9,12,20,21

Intraoperatively, adequate perfusion and oxygenation are essential to reduce the incidence of AKI.8,9 In our study, longer, open surgeries with restrictive fluid therapy and greater haemodynamic instability were associated with a higher risk of PO-AKI, an observation echoed by other authors.8,9,12,20,21 Specifically, open surgery was the approach with the highest incidence of PO-AKI, probably due to its greater complexity and greater fluid loss.

Patients who developed PO-AKI were more likely to require ICU admission, had a positive AKIRisk score, and presented episodes of haemodynamic instability, which led to an increased need for transfusions, mechanical ventilation, diuretics, and increased the risk of postoperative complications.

In the multivariate analysis, the factors most strongly associated with PO-AKI were male sex, ICU admission, and a positive AKIRisk score.

Utility of the AKIRisk score and KDIGO recommendationsThe presence of a positive AKIRisk score correlated with the development of PO-AKI, as reported in previous studies.3,7,10,11,13 In our study, 63% of patients who developed PO-AKI had a positive AKIRisk score, although this corresponded to stage 1 in the majority of cases, a finding consistent with existing evidence.7–9

TIMP-2 × IGFBP7, among available biomarkers, has shown robust PO-AKI prediction results. Gunnerson et al. reported an AUC of 0.84 (95% CI: 0.76−0.90) for the prediction of moderate to severe PO-AKI in the first 12 postoperative hours.22 Likewise, Gocze et al. found that TIMP-2 × IGFBP7 significantly improved AKI risk assessment in high-risk surgical patients, with an AUC of 0.85 for any stage of AKI and 0.83 for early need for renal replacement therapy.23 In patients undergoing cardiac surgery, the sensitivity of TIMP-2 × IGFBP7 for predicting AKI has been reported at approximately 77%.24 These differences suggest that although TIMP-2 × IGFBP7 is a valuable tool for predicting PO-AKI, its sensitivity varies according to the type of surgery, and it is higher in major abdominal surgery.

The AKIRisk score has consolidated its position an effective tool for early identification of patients with kidney stress that require prompt application of kidney protection measures.6,12,13,17,25,26 However, in our cohort of ICU patients with a positive AKIRisk score, implementation of the KDIGO guidelines did not appear to significantly reduce the incidence of PO-AKI. Our study does not include a control group, because excluding a group of patients from receiving KDIGO kidney protection measures would have been unethical. Nevertheless, the absence of a control group limits our ability to accurately assess the effectiveness of these measures, although they appear to have helped reduce the severity of PO-AKI, as only 6.5% of cases progressed to KDIGO stages 2−3. The limited effectiveness of KDIGO measures in our population could be due to several factors: (1) late start of kidney optimization, (2) no early consultation with a nephrologist (3) presence of pre-existing kidney disease when KDIGO measures were implemented, and (4) kidney optimization factors not included in the KDIGO recommendations. Tissue and organ congestion, including kidney congestion, has gained relevance as a risk factor for the development of PO-AKI. Using ultrasound to evaluate congestion (VExUS) could play a key role in reducing its incidence.6,27,28 Administering fluids without considering the degree of kidney congestion could have led to fluid overload, which in turn would exacerbate tissue and kidney congestion, compromise kidney perfusion, and aggravate ischaemia.

Regarding other biomarkers, a recent meta-analysis showed that urine NGAL was the most accurate biomarker for diagnosing PO-AKI in non-critical patients,25 although its performance has been less consistent in surgical patients. In other studies, serum cystatin C compared to several other biomarkers has shown the highest diagnostic accuracy for PO-AKI after major surgery, with an HSROC value of 82%.26 However, the rapid response capacity of TIMP-2 × IGFBP7 and its effectiveness in the early detection of PO-AKI position it as a valuable tool in perioperative management. Combining the AKIRisk score with other kidney damage biomarkers such as creatinine-corrected urine NGAL could improve its predictive capacity and allow early detection of intra- or postoperative kidney damage.25

Our study follows standard clinical practice in major abdominal surgery, where the decision to admit to the ICU is based on independent clinical criteria, such as the type of surgery, intraoperative outcome, and postoperative haemodynamic status, irrespective of the patient’s inclusion in our study. Although it was impossible to measure urine output every 6 h or routinely apply KDIGO measures in patients treated on the ward, we decided to include them in order to provide a comprehensive overview of the incidence of PO-AKI. Despite the limitations of our findings, we believe they provide important information that may be useful in future strategies to improve perioperative management.

LimitationsThis study has several limitations. Its single-centre observational design may limit the generalizability of the findings. Differences in the characteristics of patient admitted to the ICU and managed on the ward, where KDIGO recommendations were not routinely applied and urine output could not be recorded every 6–12 h, could affect the accuracy of our assessment of the development of PO-AKI in this subgroup. Nevertheless, these differences are to be expected in real-world clinical practice, and we believe that the inclusion of both groups provides a broader, more representative view of the overall incidence of PO-AKI in major abdominal surgery.

Although we use the accepted Nephrocheck® cut-off values, they can vary depending on the population studied,11,12,14,15 and this could affect the accuracy of the biomarker used in our study. The lack of an ICU control group that did not receive KDIGO measures for ethical reasons limits our ability to accurately assess the impact of these interventions.

Another limitation is the absence of certain important clinical variables, such as albuminuria, urinary sediment, systemic markers of inflammation, or preoperative optimization strategies, which could introduce confounding factors.

Finally, although standardized protocols were applied, variability in clinical practice among anaesthesiologists and individual experience in implementing KDIGO recommendations could have influenced outcomes due to differences in the perioperative management of patients.

ConclusionThe incidence of PO-AKI in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery was as high as 25.3%. Kidney stress biomarkers can identify patients at increased risk for PO-AKI, and could be a useful tool for selecting those who would most benefit from renal optimization strategies. This would reduce the severity of postoperative AKI and improve clinical outcomes.

Despite the implementation of KDIGO renal protection measures in the ICU, the incidence of PO-AKI in these patients remained high. However, these interventions could have helped prevent progression to more advanced stages. These findings underscore the need to improve prevention and management strategies for PO-AKI, especially in vulnerable populations.

Multicentre, prospective, randomized studies are needed to validate these results and optimize intervention strategies.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest

![Postoperative acute kidney injury (PO-AKI) and positive AKIRisk score (Nephr. ↑ = [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] > 0.3 (ng/ml)2/1000). Postoperative acute kidney injury (PO-AKI) and positive AKIRisk score (Nephr. ↑ = [TIMP-2] × [IGFBP7] > 0.3 (ng/ml)2/1000).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/23411929/0000007200000007/v3_202509160448/S2341192925001477/v3_202509160448/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)