The reporting of intellectual capital in higher education institutions becomes of vital importance mainly due to the fact that knowledge is the main output and input in these institutions. Also, the increasing social concern about establishing procedures of accountability and ensuring information transparency in public universities prompted us to raise the need to disclose information on their intellectual capital. This paper aims to know the main reasons why Spanish universities do not disclose information about their intellectual capital in the current accounting information model and the positive consequences that may result from such disclosure. To this end a questionnaire was designed and sent to all the members of the Social Councils of Spanish public universities. The obtained results show that intellectual capital disclosure results in a higher transparency of the institution, increased user satisfaction and improved credibility, image and reputation of the University, while it is the lack of internal systems of identification and measurement of intangible elements the main reason for not disclosing information on intellectual capital.

La presentación de información sobre capital intelectual en las instituciones de educación superior llega a ser de gran importancia principalmente debido al hecho de que el conocimiento es el principal output e input en estas instituciones. Asimismo, la creciente preocupación social por establecer procesos de rendición de cuentas y por asegurar la transparencia informativa de las instituciones públicas de educación superior nos lleva a plantear la necesidad de que las universidades españolas divulguen información sobre su capital intelectual. De este modo, el principal objetivo de este trabajo es conocer los principales motivos por los que las universidades españolas no divulgan información sobre su capital intelectual en el actual modelo de información contable universitario y las consecuencias positivas que podrían derivarse de dicha divulgación. Para ello, se elaboró un cuestionario que fue enviado a la totalidad de miembros de los Consejos Sociales de las universidades públicas españolas. Los resultados obtenidos muestran que, en opinión de los miembros de los Consejos Sociales de las universidades públicas españolas, la divulgación de información sobre capital intelectual conllevaría un aumento de la transparencia de la institución, un aumento de la satisfacción de los usuarios y una mejora en la credibilidad, imagen y reputación de la universidad. Mientras que es la falta de sistemas de información internos para identificar y medir los elementos intangibles el principal motivo por el que las universidades no divulgan dicha información.

The modernization of the Spanish university system is a process that has been put in place to respond to globalization and internationalization, to facilitate differentiation and to respond to the challenges of increased national and international competition.

From our point of view, we understand that reforms in the university system are important, not without difficulties linked to the current circumstances, but this forces us, even more, to develop an ambitious and future key.

Our universities must be characterized by some attributes and values that enable them to meet the challenges of a global market. Globalization of the political economy, and the attendant reductions in government funding, liaisons with business and industry, and marketing of educational and business services, has been changing the nature of academic labor (Slaughter & Leslie, 1997). Society requires us quality training focused on values and fosters critical thinking and ethical behavior. But also demands a commitment to innovation, knowledge transfer to society and that the university is a key tool for social, cultural and economic. Undoubtedly, all directly affect the governance model of the university. Universities have been caught up in the international surge in interest in governance of organizations (Coaldrake, Stedman, & Little, 2003).

Governance in higher education refers to the way in which institutions are organized and operate internally and their relationships with external entities with a view to securing the objectives of higher education as a realm of enquiry and critique. It includes informal mechanisms such as traditions, implicit beliefs, mental models, patterns of behavior, values internalized by the culture of communities, organizations and groups that act, but also formal structures as, the hierarchy, the processes, the written rules and devices of coercion, control and accountability. A greater preponderance of formal responsibility for all that happens in a university is being vested in a governing body, board or council. Increasingly, this comprises elected, appointed and ex-officio members, many of them in non-executive roles and all expected to shoulder a corporate responsibility, rather than only representing the interests of particular constituencies, such as staff, students and funding bodies (Dixon & Coy, 2007:267).

Universities must acquire a model of governance to strengthen institutional autonomy, but also with greater transparency toward society and greater control over the results. Governments wish to assure that the actions of publicly funded universities are consistent with the social values of efficiency, equity, and academic quality (Dill, 2001:22). Therefore, from our point of view, autonomy and accountability are two sides of the same coin. What is needed in this sensitive area, then, is a suitably sensitive buffer mechanism which can reconcile the Government's legitimate need for accountability and the universities’ vital need for maximum autonomy consonant with that accountability (Berdahl, 1990). When we talk about autonomy, we mean organizational autonomy, financial and management, independent management of personal and academic structure. An instrument to carry out an effective accountability is evaluation, a proper system of assessment, must be fair and differentiator to ensure fulfillment of the objectives of the university.

Therefore, if we want to guarantee the autonomy we have to ensure proper accountability. It is essential that the university reports impacts and the results achieved, taking into account the context variables, the process in which it operates and the more commonly accepted international standards.

In this socioeconomic context, with a need for information transparency, reporting on intellectual capital becomes crucial in the universities, mainly due to the fact that knowledge is the main output and input in these institutions. Thus, what the university produces is knowledge, either through scientific/technical research (research results, publications, etc.) or through teaching (trained students and productive relationships with their stakeholders). Also, among their most important assets are their teachers, researchers, staff and services of administration, university governance, and students, along with their organizational processes and networks of relationships (Leitner, 2004; Warden, 2004). So it can be said that both its inputs and its outputs are mainly intangible (Ramírez, Santos, & Tejada, 2011). The higher education institutions are, therefore, an ideal framework for the application of the ideas related to intellectual capital theory.

Specifically, the term intellectual capital within universities is going to be used to cover all non-tangible or non-physical assets of the institution, including its processes, capacity for innovation, patents, tacit knowledge of its members, their abilities, talents and skills, the recognition of the partnerships, its network of collaborators and contacts, etc. (Bezhani, 2010; Bodnár, Harangozó, Tirnitz, Révész, & Kováts, 2010; Casanueva & Gallego, 2010; Ramírez, Lorduy, & Rojas, 2007; Secundo, Margheritam, Elia, & Passiante, 2010; etc.). So, the intellectual capital is the set of intangibles that “allows an organization to transform a set of material, financial and human resources in a system capable of creating value for stakeholders” (European Commission, 2006:4).

Other reason that justify the importance and need to establish a diffusion model of intellectual capital at the university is the existence of continuous external demands from a greater information and transparency about the use of public funds (Coy, Tower, & Dixon, 2001; Warden, 2004), which is fundamentally due to the continuous process of decentralization, both academically and financially, experienced by higher education institutions. In this way, it should be noted that universities, as major producers of knowledge, become key institutions in the current economy, being as a result subjected to a greater monitoring in their performances on the part of all its surroundings (European University Association, 2006:19). In this situation, the proper presentation of institutional communication becomes currently one of the main mechanisms of statement of accounts for higher education institutions.

Another reason for universities to begin to publish information about their intellectual capital is that they have to compete to obtain funds. Currently, universities are facing an increasing competition for scarce funds, thus finding more pressure to communicate their achieved results (European University Association, 2006; González, 2003; Sánchez & Elena, 2007; Secundo et al., 2010). Universities should link governance, autonomy, accountability and evaluation. It is essential to ensure the quality of the system. Economic incentives are essential. The tool to link them is a program contract, which establishes the strategies and priorities of the University.

Therefore, accountability of needs are increased by the universities, which entails that the university must be able to provide objective and relevant information to guarantee meeting the information needs of its users. In this regard, we note that the financial information relating to the universities is not only the type of information required by the vast majority of stakeholders, since they are more interested in knowing the quality and the evolution of performances related to specific activities of the institution and not just its financial results (Machado, 2007). Thus, universities must incorporate into their institutional communications strategy a greater attention to their stakeholders and their respective information interests, making necessary to incorporate relevant information about their intangibles, such as aspects of the quality of the institution, corporate image, their social and environmental responsibility, the capacities, competencies and skills of their staff, etc. (European Commission, 2006; Leitner, 2004; Machado, 2007; Ramírez et al., 2011).

On this point we should clarify that, with some frequency, it is argued that it is impossible to assess the intangible and, therefore, any change in the current practices of financial information publishing should not carried out. This assertion reflects the existing confusion between aspects related to the measurement of intangibles and the ones related to the publishing of information about them. In our opinion, the current difficulties in the valuation of intangibles (a measurement problem) should not be an obstacle to the publishing of information in the notes to the financial statements or by other means (Lev, 2003:121), since such information is useful for financial statement users.1 Similarly, the FASB (2001:4–5) justifies the disclosure of information on the intangibles not recognized under the following terms: “despite continuing strong reasons for the establishment of restrictive criteria limiting the recognition of internally generated intangibles, it becomes necessary to find better ways to inform users of financial reports on intangible assets (…). Without the development of such approaches, the accounting may face a serious loss of credibility while intangible assets become more and more important”.

However, despite the aforementioned lines, it is verified that in most countries there is a total absence of obligation or even recommendation of reporting on intellectual capital on the universities’ behalf, except the case of Austrian universities (Leitner, 2004). Given this lack of “must do” or simple recommendation from political authorities and university administrators to present this information, it is appropriate to do research highlighting the reasons why higher education institutions should prepare and disseminate information on its intellectual capital and also the reasons they might have to not do it. Also, note that research about intellectual capital reporting in higher education institutions is still incipient, especially if we compared with the business scope. And, as the benefits and costs of Intellectual Capital Reports for Spanish universities have not been examined systematically and comprehensively so far this paper aims at a basic contribution to this topic of current interest. All these aspects strengthen and justify the originality, opportunity and utility of our research.

Our paper is based on the Stakeholder Theory (Atkinson, Waterhouse, & Wells, 1997; Donaldson & Preston, 1995; Freeman, 1984; Frooman, 1999; Harrison & Freeman, 1999; Mitchell, Agle, & Wood, 1997; etc.), whose main postulate is that the proper way to get a competitive edge by organizations requires the maintenance and/or creation of adequate relations with each of the groups that are of interest, stakeholders (Castilla & Gallardo, 2008:82). According Husillos and Álvarez-Gil (2008:128), to study the behavior of organizations from the perspective of Stakeholder Theory has helped us understand, for example, the role that institutions should play in society (Donaldson & Preston, 1995). This has also helped to identify how the processes of wealth creation in organizations (Post, Preston, & Sachs, 2002). This theory has played a crucial role in the dimensioning of the abstract notions of corporate social responsibility and performance (Clarkson, 1995). Finally, it has also highlighted the relationship between the importance given by managers to the interests of certain stakeholders and behavior more respectful of the organizations, both from the environmental point of view, as the overall sustainable development (Sharma & Henriques, 2005).

Thus, based on the Stakeholder Theory, this paper will try to determine the importance given by users of university accounting information to intellectual capital disclosure. In particular, our empirical research aims to analyze the opinions of the members of the Social Councils of the Spanish public universities regarding the main benefits and costs derived from the implementation of a proactive policy of intellectual capital property publishing.

The paper is structured as follows. In Reporting on intellectual capital in higher education institutions: costs and benefits section we will first review the existing literature on the presentation of information on intellectual capital in higher education institutions. This section also includes a cost-benefit analysis of reporting intellectual capital. Then we will define the scope of the empirical study conducted and the methodology used and finally we will present our results and conclusions.

Reporting on intellectual capital in higher education institutions: costs and benefitsCurrent accounting regulations restrict the recognition of intangibles. Only acquired intangible assets may be reflected in an organization's balance sheet (Cañibano, Gisbert, García-Meca, & García-Osma, 2008). For this reason, there are numerous organizations, entities, and academics that aware of the difficulty to incorporate intellectual capital with the current rules, tend to recommend the development and presentation of Intellectual Capital Reports (Abeysekera, 2006; Ramírez, 2010). Intellectual capital reports contains a set of indicators that contribute to improving the quality of accounting information for organizations.

The instrument of intellectual capital report and the general methods for valuing intangible within universities finds its justification from one hand in the political and managerial challenges that require the implementation of new management and reporting systems in order to improve intellectual capital internal management and to disclose information to stakeholders, from the other hand in the consideration that national and supranational organisms recognize a central role to universities in the actual knowledge-based society (Silvestri & Veltri, 2011).

The introduction of the obligation to submit an Intellectual Capital Report in the higher education system serves as a crucial step forward for the new university management, thereby achieving a double objective: identifying and measuring intangibles for management purposes and providing useful information to stakeholders.

This section focuses on presenting the main experiences in reporting intellectual capital within universities.

One of the major initiatives related to the preparation and reporting of intellectual capital in higher education institutions is the one of Austrian universities. Since 2007, they are required to file Intellectual Capital Reports. Specifically speaking, UG2002, Article 13, established the obligation and general framework for developing these Intellectual Capital Reports (called Wissensbilanz). According to UG2002 (Section 13, Subsection 6), the Intellectual Capital Report shall include, at the minimum, the following elements:

- •

“University activities, social and voluntary goals and strategies;

- •

Their intellectual capital, divided into human, structural and relational capital;

- •

Processes presented in the performance contract, including their outputs and impacts” (Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Austria, 2002).

Within this Intellectual Capital Report, each university must submit indicators of input, output, research performance, teaching, and third mission activities.

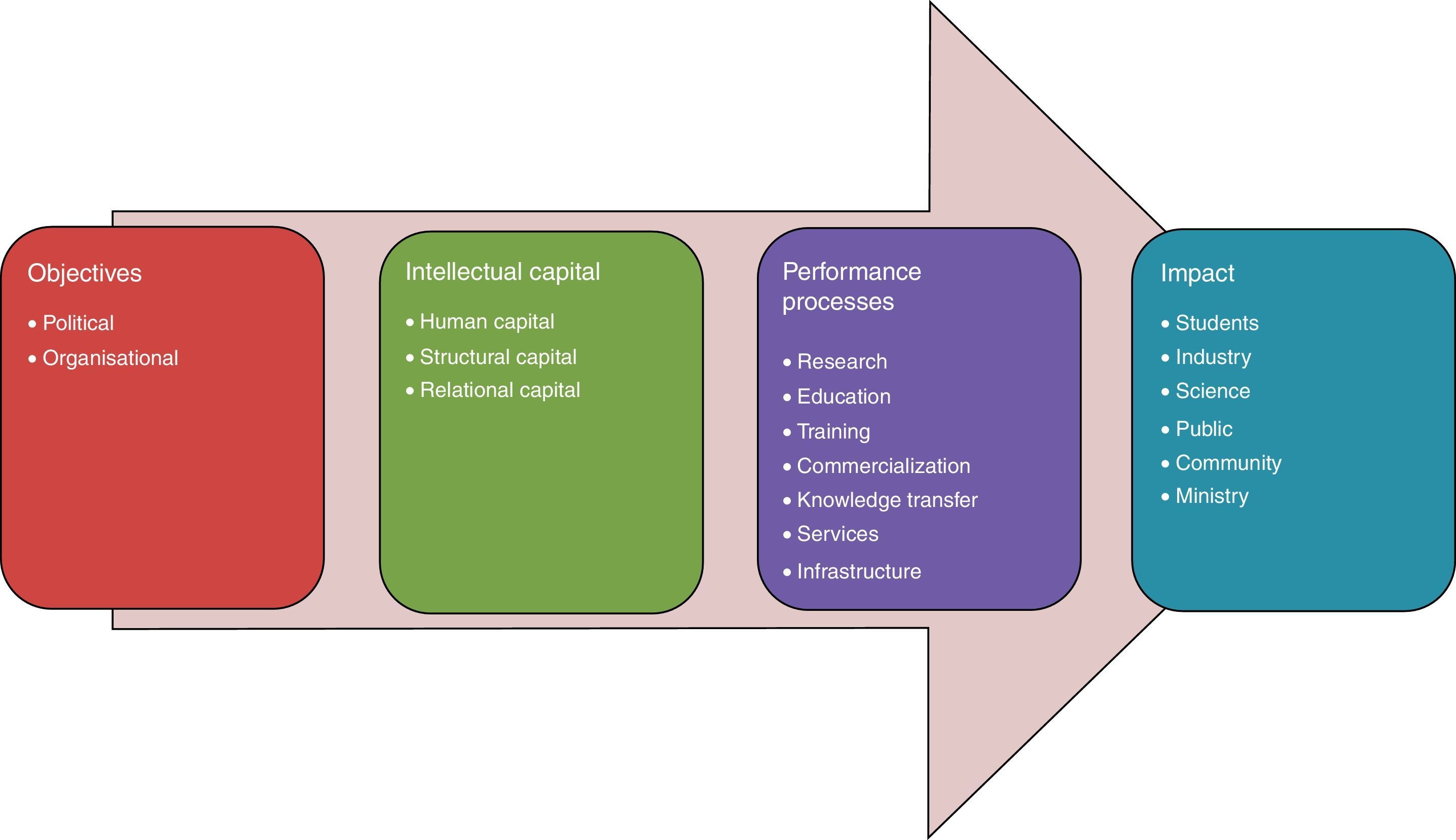

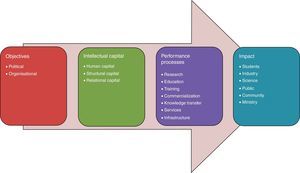

The base model of the Intellectual Capital Report described in UG2002 was developed by Schneider and Koch. It is based on the model and principles developed by the Austrian Research Center, a pioneering European research institution that applies intellectual capital models to manage intangibles and then submit this information (Leitner, 2005). This model attempts to visualize the process of knowledge production within universities. It is composed of four main elements (see Fig. 1). The various elements of the model will be measured by quantitative and qualitative indicators.

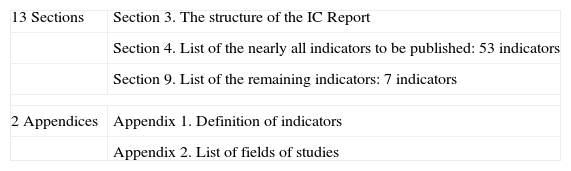

Finally, the way to submit the information and required indicators that are to be published in the detailed structure of the University Intellectual Capital Report were regulated by an Order of the Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Culture published on February 15, 2006. This Order comprises 13 sections and 2 appendices. The next Table 1 summarizes the central issues.

Intellectual Capital Report order: main contents.

| 13 Sections | Section 3. The structure of the IC Report |

| Section 4. List of the nearly all indicators to be published: 53 indicators | |

| Section 9. List of the remaining indicators: 7 indicators | |

| 2 Appendices | Appendix 1. Definition of indicators |

| Appendix 2. List of fields of studies | |

The structure of the intellectual capital report includes the following sections (see Table 2).

Order of the Federal Ministry of Education, Science and Culture on Intellectual Capital Reports.

| Structure of the Intellectual Capital Report |

| I. Scope of application, objectives and strategies |

| II. Intellectual property |

| 1. Human capital |

| 2. Structural capital |

| 3. Relation capital |

| III. Core processes |

| 1. Education and continuing education |

| 2. Research and development |

| IV. Output and impact of core processes |

| 1. Education and continuing education |

| 2. Research and development |

| V. Summary and prospects |

This legal implementation of intellectual capital report (ICR) for Austrian universities represents a courageous step forward to a future-oriented reporting system. However, Altenburger and Schaffhauser-Linzatti (2005) analyze this Intellectual Capital Report, focusing on the problems at external (regarding stakeholders) and internal level (for the university). The main external problems of ICR are: (1) this planned ICR design concentrates on statistical, quantitative data, similar to traditional reporting instruments. The ICR model should treat qualitative and quantitative information with equal priority; (2) the ICRs of all universities have to follow the instructions of the Order and consequently are based on the identical model with identical indicators. However, the same indicator could have different meanings and interpretations; and, (3) the difficulties in comparing indicators of different subunits have shown that the implementation of the model for a whole university with very heterogeneous departments will lead to results of restricted usefulness and relevance. Finally, the main internal problems of ICR identified by these authors are: (1) the universities will probably adjust their strategies only to the indicators specified in the Order and will try to intensify those activities which improve the decisive indicators. Therefore, important specific processes and aspects could be disregarded; (2) because of this reduction of individual freedom ICRs could be perceived by the employees as a monitoring instrument, what could lead to a reduction in motivation and loyalty; (3) the underlying ICR structure gives a lot of leeway in preparing and interpreting the provided information which causes substantial subjective influence on the ICR results; (4) university reporting model is based on the calendar year while university activities are organized in academic years (Table 3).

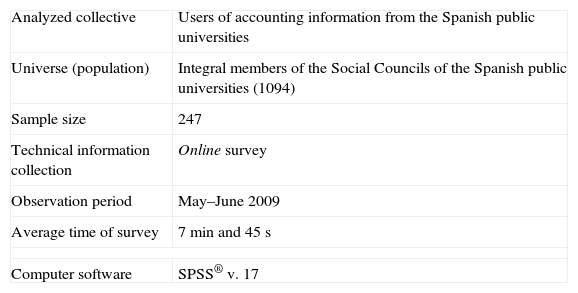

Technical details of the study.

| Analyzed collective | Users of accounting information from the Spanish public universities |

| Universe (population) | Integral members of the Social Councils of the Spanish public universities (1094) |

| Sample size | 247 |

| Technical information collection | Online survey |

| Observation period | May–June 2009 |

| Average time of survey | 7min and 45s |

| Computer software | SPSS® v. 17 |

In our opinion, the main problem of this ICR model is the selection of indicators has been made in general terms to allow comparability among Austrian universities so there is no direct link between the set of indicators and the university's strategic plan.

Other relevant proposals for reporting on intellectual capital for higher education institutions were made by the Poznan University of Economics (UEP) in Poland and the Electronics and Telecommunications Research Institute (ETRI) of South Korea. Fazlagic (2005) of UEP had prepared an Intellectual Capital Report using the methodology proposed by the Danish Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (2000), which presents intellectual capital in the form of resources, activities, and results. In 2001, ETRI began to develop and establish an effective management tool and corresponding knowledge management system. Since 2004, ETRI publishes reports on intellectual capital annually (ETRI, 2005).

On the other hand, one of the main objectives of the Observatory of European Universities (OEU), which was created in June of 2004, is to understand the importance of managing public university intangibles to improve their level of quality and competitiveness (Sánchez & Elena, 2006:538). One of the most relevant final results from OEU (that had been developed by a research team from the Autonomous University of Madrid) was the presentation of an Intellectual Capital Report specifically designed for universities and research centers – called ICU Report (Sánchez, Elena, & Castrillo, 2007). This report aims to improve transparency and to constantly assist the homogeneous dissemination of intellectual capital indicators. The proposed Intellectual Capital Report consists of three essential sections that describe the logical movement from internal strategy and management (design of the vision and objectives of the institution) toward a system of indicators (OEU, 2006:211): (a) vision of the institution; (b) intangible resources and activities; and (c) a system of metrics (Cañibano, Sánchez, García-Ayuso, & Chaminade, 2002).

Then, we show the main benefits and costs of reporting intellectual capital.

Generally speaking, the main benefits associated with reporting intellectual capital are:

- •

Increasing institutional transparency regarding the use of public and private funds;

- •

Improving the image or reputation of the institution (Babío, Muiño, & Vidal, 2003; Caprioti, 2004:63) since it conveys a positive image of transparency and willingness to report;

- •

Assisting to inspire confidence among/between institutional employees and other stakeholders (i.e. employees would know the training efforts, competences and motivations; customers would know to what extent the company is making efforts to retain them and satisfy their demands; etc.);

- •

Reducing information asymmetries between insiders and outsiders (Cuganesan, 2005; Holland, 2001; Starovic & Marr, 2003) since it increases the informative position of stakeholders on the progress of the organization, clients, suppliers, owners, Public Administrations, employees and other users;

- •

Enhancing institutional, long-term vision by communicating a long-term prospect (Backhuijs, Holterman, Oudman, Overgoor, & Zijlstra, 1999);

- •

Improving institutional management that will require rational decision-making to better define strategic objectives (Castilla, Chamorro, & Cámara, 2006).

The main drawbacks derived from external information publishing on intellectual capital include the following:

- •

High costs of collection, data-processing, elaboration, and dissemination (Larrán & García-Meca, 2004; Meer-Kooistra & Zijlstra, 2001);

- •

Increased operating costs as a result of new rules and bureaucracy (Backhuijs et al., 1999);

- •

Possible manipulation of information and subsequent favoritism (Backhuijs et al., 1999);

- •

Competitive disadvantage costs that refer to the fear an institution possesses when disclosing too much self-information (Williams, 2001:201) for fear of damaging their competitive position (Babío et al., 2003). In this sense, Castilla et al. (2006) consider that “the standardization of the informative supply on intangibles can significantly reduce the cost of competitive disadvantage for companies, by allowing to homogenize the items that will be disclosed”;

- •

Creating user-risk through unjustifiable, provisional reporting (Backhuijs et al., 1999).

The organization's management will use a cost-benefit analysis that will determine the appropriate choice of policy regarding Intellectual Capital Report.

Empirical studyThe empirical work will support the following two objectives:

- •

Objective I: To determine the importance given by users of university accounting information to intellectual capital disclosure.

- •

Objective II: To identify the reasons that can lead universities to find the disclosure of intellectual capital advantageous, as well as those that have prevented such disclosure.

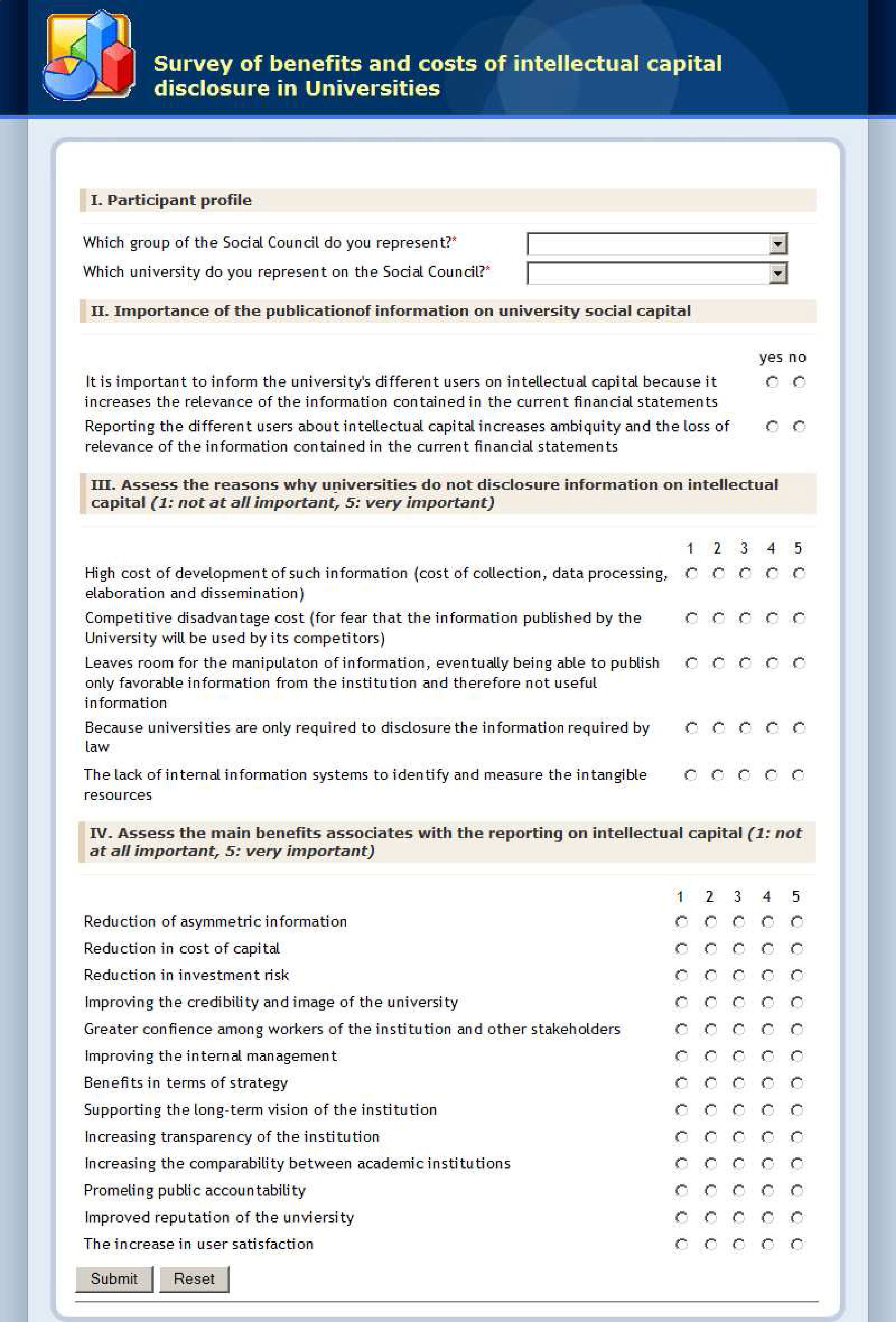

In May 2009, an online questionnaire was sent to the members of the Social Councils of all the Spanish public universities in order to know their opinion about the need to incorporate relative intellectual capital information within university accounting reports. A summarization of the study's methodology is highlighted below.

Demarcation of the population and sample selectionThe justification for the choice of population stems from two important reasons: (1) members of Spanish public universities’ Social Councils are an excellent example as users of university information, offering a wide variety of perceptions within the university system, and (2) they are the authorities who present and publish university accounting, especially those who approve the university's annual accounts.

Besides, since members of the Social Councils are primarily directors and managers who are responsible for the annual university accounting, it will be interesting to determine their individual opinions as issuers of such information and the reasons why universities do not disclose information on intellectual capital.

After reviewing the literature dedicated to the analysis of stakeholders in universities (Gaete, 2009; Jongbloed, Enders, & Salerno, 2008; Larrán, López, & Calzado, 2010; O’dwyer, 2005; Okunoye, Frolic, & Crable, 2008), a certain consensus was detected once the following users of the accounting information of the higher education institutions were identified: the public administration, bodies of university government, students, teaching and research staff, administration and service staff, unions, private and public organizations with plans to employ university graduates or to apply the research generated at the institution, the media, the unions and agencies of accreditation and quality assessment foundations or any other party interested in university activity.

After analyzing the composition of the Social Councils of the public Spanish universities, it is evident that they all appear as members: the rector, general secretary, manager, council secretary, a president, a representative of teaching and research staff, a representative of administration and services staff, a representative of students, between 2 and 6 (usually 2) representatives of business organizations, between 2 and 6 (usually 2) representatives of union organizations, and various representatives of the Regional Government, the Regional Parliament, the Town Hall, the regional courts, of the Federation of Municipalities and Provinces, and so on, which have been included within the group called Public Administration.

In order to carry out a further analysis of contrast that allows us to know if there are differences in the opinions of the different groups, the members of the Social Councils have been grouped in the following three collectives: (1) University Government: includes the Rector, General Secretary, Council Secretary and Manager; (2) External Users: includes students and representatives of business organizations, trade unions, and public administrations; and (3) Employees: teaching/research staff and administrative/services staff. Although the employees are part of university governing bodies through the University Senate, it is considered interesting to know their opinion individually.

Hence, the population is composed of 1094 integral members of the Social Councils, with 247 members responding to the survey, yielding a 22.57% response rate. The sample size is considered to be sufficient, with a binomial population estimation error of 5.37% with a 95% confidence level.

Information collection and treatmentSocial Council members had been surveyed through e-mail invitations containing access links to an online questionnaire. This questionnaire consisted of closed questions (a simple dichotomous response combined with Likert scales) to obtain the opinions of accounting information users regarding the importance of incorporating Spanish public universities’ intellectual capital information in their annual reports. This included the costs and benefits associated with the disclosure of such information (see Appendix A).

Responses were subjected to a descriptive analysis based the characteristics of each question. Also, a Nonparametric test (the Kruskal–Wallis test) was used to see if there were differences in responses by type of accounting information user.

Analysis of results of the empirical studyThe main results obtained through the empirical study are as follows.

Objective 1: To know the importance given to the disclosure of information on intellectual capitalGiven the reduced presence of intangibilities within the accounting information of Spanish public universities in lieu of mandatory elaboration, knowing the opinion of the users of accounting information is considered to be relevant regarding the university convenience to publish such information.

In this regard, of those who participated in the study, 89.1% reported to show a high interest in the disclosure of intellectual capital by Spanish public universities, considering that such disclosure would increase the relevance of the information contained in the current university financial statements. When differentiated by user-groups, we found that virtually all users [public administrations (89.4%); students (100%); business organizations (86.2%); teaching and research staff (95.5%); university governance (97.4%); members of administration and services staff (66.7%), and trade unions (76.5%)] consider that the university reporting of intellectual capital increases the relevance of the information contained in current financial statements.

Only 4.9% of respondents consider that reporting intellectual capital to different users increases ambiguity and loss of relevance regarding the information containing the current financial statements. Concluding in this set of questions, it should be noted that a strong emphasis on the need for universities to submit information on their intellectual capital has been proved.

Objective 2: Perceptions of costs and benefits of disclosure of intellectual capitalThe purpose of this block of the questionnaire is to know from the Social Council members the main reasons why universities do not disclose information about their intellectual capital in the accounting reports and the positive consequences that would result from such publication. The perceptions of respondents on both counts were measured over a 5-point Likert scale (1–5, 1 being “not at all important” and 5 being “very important”). It was also analyzed if these views depend on the collective of users represented by the Social Council members, who have been divided into three groups: university governance, employees, and external users.

- •

Perceptions of benefits linked with the reporting of university intellectual capital

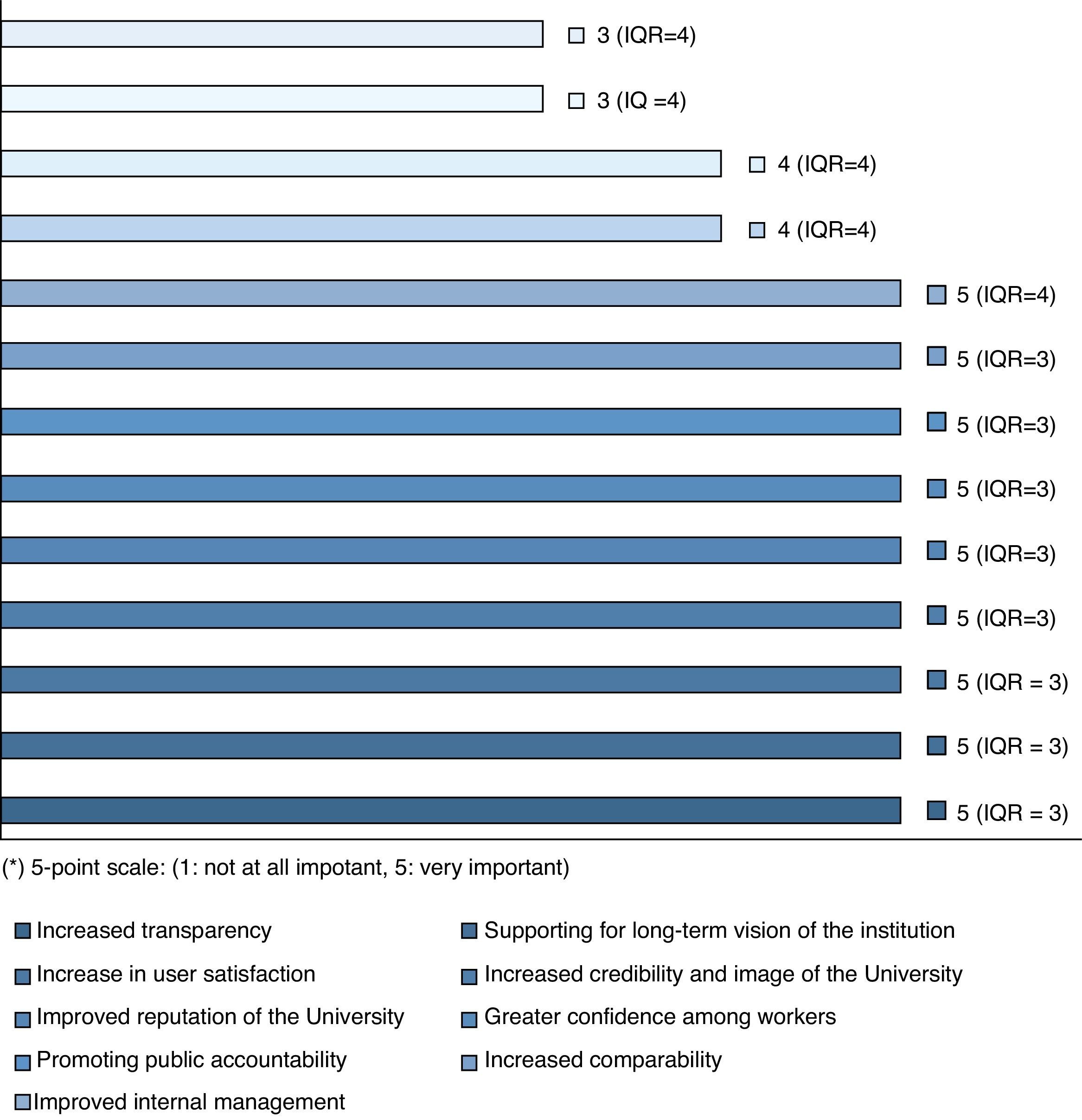

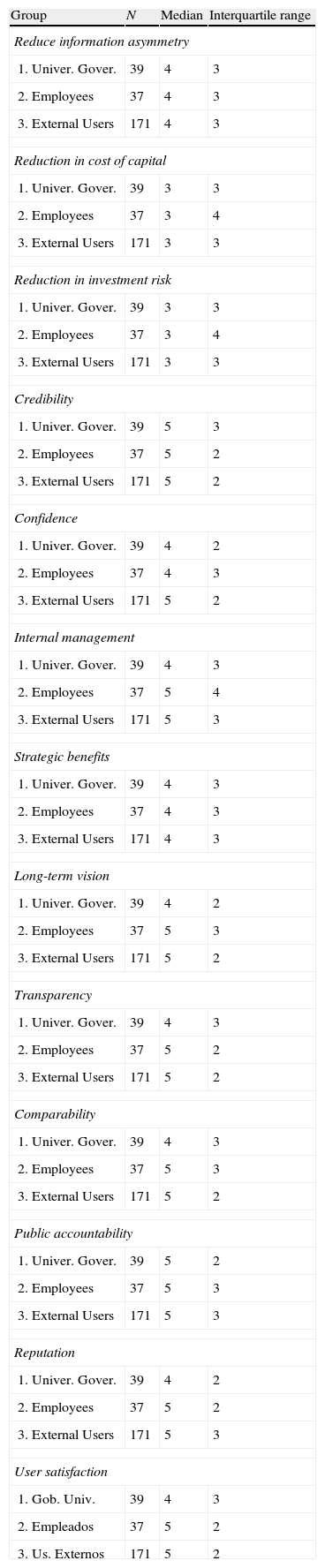

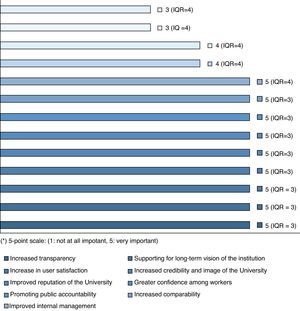

The analysis of respondents’ opinions concerning the possible beneficial effects of intellectual capital reporting shows (Fig. 2) that great benefits are expected from the existence of an intellectual capital disclosure policy. Such benefits that contribute to a positive, long-term vision of the university include improvements in credibility and reputation with increased transparency and user satisfaction. The high ratings that reach these beneficial effects (median value equal to 5) indicate a high degree of consensus among all respondents about the important contribution that information on intellectual capital can do for user satisfaction and the image of the University. The benefits directly associated with improved confidence also receive a significant valuation among university workers and other stakeholders. This promotes public accountability by increasing the comparability between academic institutions while improving the internal management as information asymmetry is reduced.

Finally, note that the last positions correspond to the reduction in investment risk and cost of capital. These results are similar to those obtained in the work of Babío et al. (2003), although, in a business setting. Apparently, respondents did not attach much importance to intellectual capital reporting to a reduction in the cost of capital, which may be a result of the fact the financing of universities comes mainly from central and regional governments.

Fig. 2 shows the median and interquartile range (IQR) values for each item of the questionnaire related to the benefits of publishing information on intellectual capital.

The high mark obtained by the advantage of serving as a means to increase the information transparency of the universities – 75.3% of respondents consider it to be very important – allows us to justify the need to disclose information on intellectual capital as a necessary step to achieve the goal of “transparency of information. as was established in the University Strategy 2015 (Secretaría de Estado de Universidades, 2008). Also worth noting is that the majority of employees (86.4% of teaching and research staff and 93.3% of administration and services staff) consider that the disclosure of information regarding intellectual capital acts in favor of strengthening and/or improving the relationship between the universities and the groups of employees because it is assigned to release certain aspects that are not reflected in the required information from a legal standpoint. As a result, the confidence and trust in university employees improves.

On the other hand, it was analyzed whether or not these opinions depend on the user group that members of the Social Councils represent. For this purpose, the Kruskal–Wallis test allowed us to check whether there were varying views amongst the different groups of users and whether they were statistically significant. This test is most appropriate for small groups’ contrasts and when the variables do not meet the normality hypothesis (as it is our case).

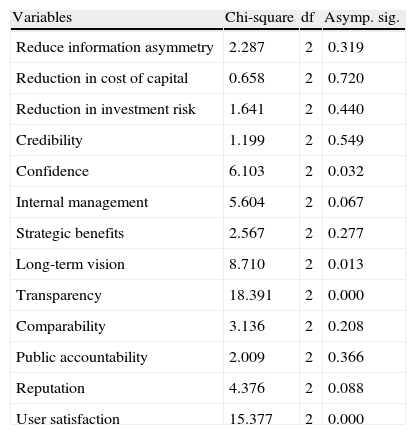

To carry out the Kruskal–Wallis test, the p-value (Sig.) is obtained with a critical level of 0.05 to determine if the variables included in the analysis show significant differences between the three groups formed (see Table 4).

Differences in perceptions of benefits among user groups (Kruskal–Wallis test) (test statistics).a,b

| Variables | Chi-square | df | Asymp. sig. |

| Reduce information asymmetry | 2.287 | 2 | 0.319 |

| Reduction in cost of capital | 0.658 | 2 | 0.720 |

| Reduction in investment risk | 1.641 | 2 | 0.440 |

| Credibility | 1.199 | 2 | 0.549 |

| Confidence | 6.103 | 2 | 0.032 |

| Internal management | 5.604 | 2 | 0.067 |

| Strategic benefits | 2.567 | 2 | 0.277 |

| Long-term vision | 8.710 | 2 | 0.013 |

| Transparency | 18.391 | 2 | 0.000 |

| Comparability | 3.136 | 2 | 0.208 |

| Public accountability | 2.009 | 2 | 0.366 |

| Reputation | 4.376 | 2 | 0.088 |

| User satisfaction | 15.377 | 2 | 0.000 |

The results presented in Table 4 show that there were statistically significant differences (Sig.<0.05) for four of the beneficial effects considered: supporting the long-term vision of the institution; helping to inspire trust/confidence among workers of the university and other stakeholders; increasing transparency and user satisfaction.

For its part, the analysis of the descriptive statistics for each of the groups analyzed (see Table 5) show that for the four beneficial effects (trust, long-term vision, transparency, and satisfaction) in which significant differences were found between the value assigned by the different groups of users, university governance offered a lower assessment than the one given by external users. It even gave the inferior assessment to that one given by employees to the case of the latter two benefits: transparency and user satisfaction.

Benefits of the disclosure of intellectual capital by user groups (descriptive statistics).

| Group | N | Median | Interquartile range |

| Reduce information asymmetry | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 4 | 3 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 4 | 3 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 4 | 3 |

| Reduction in cost of capital | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 3 | 3 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 3 | 3 |

| Reduction in investment risk | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 3 | 3 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 3 | 3 |

| Credibility | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 5 | 3 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 5 | 2 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 5 | 2 |

| Confidence | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 4 | 2 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 4 | 3 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 5 | 2 |

| Internal management | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 4 | 3 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 5 | 4 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 5 | 3 |

| Strategic benefits | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 4 | 3 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 4 | 3 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 4 | 3 |

| Long-term vision | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 4 | 2 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 5 | 3 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 5 | 2 |

| Transparency | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 4 | 3 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 5 | 2 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 5 | 2 |

| Comparability | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 4 | 3 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 5 | 3 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 5 | 2 |

| Public accountability | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 5 | 2 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 5 | 3 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 5 | 3 |

| Reputation | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 4 | 2 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 5 | 2 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 5 | 3 |

| User satisfaction | |||

| 1. Gob. Univ. | 39 | 4 | 3 |

| 2. Empleados | 37 | 5 | 2 |

| 3. Us. Externos | 171 | 5 | 2 |

5-Point scale (1 not at all important; 5: very important).

Furthermore, the examination of descriptive statistics allows us to appreciate that university governance members perceive the existence of lower benefits associated with the reporting of intellectual capital more than employees and external users (for all the concepts discussed), although the differences are sometimes minimal.

The previous results lead to the conclusion that employees (teaching and research staff and administration and services staff) and external users (trade unions, business organizations, students, and public administrations) greatly valued the influence of intellectual capital information on obtaining beneficial numbers to a greater extent than university governance. Specifically, external users perceive the existence of higher profits associated with increased transparency; increased user satisfaction; improved, long-term vision of the institution, and increased trust of workers more than members belonging to the university governance. There are also differences of opinion among university employees and university governance regarding the relative benefits of increased transparency and user satisfaction, since employees have higher valuations in both cases.

- •

Perceptions related to the reasons on why universities do not disclose information on intellectual capital

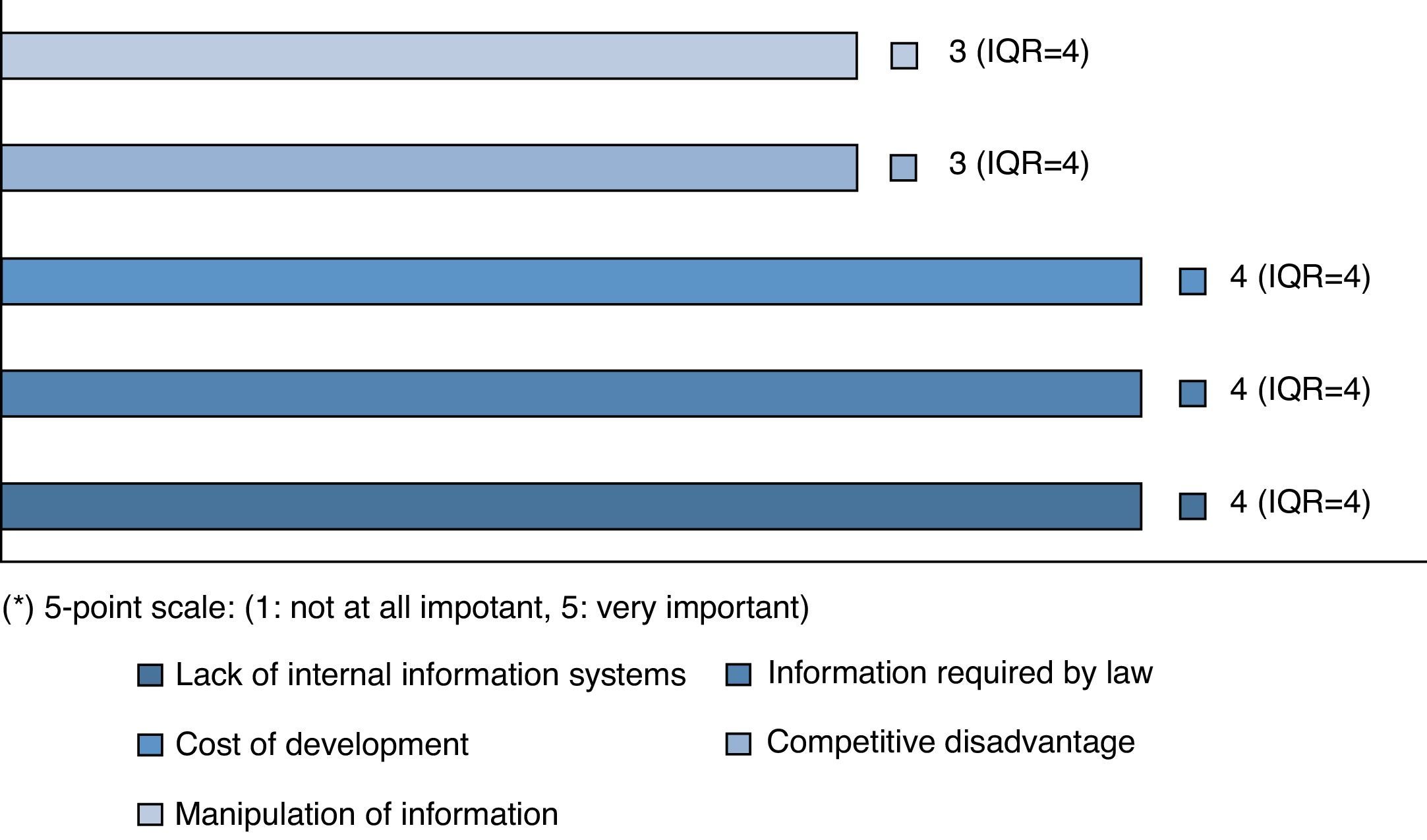

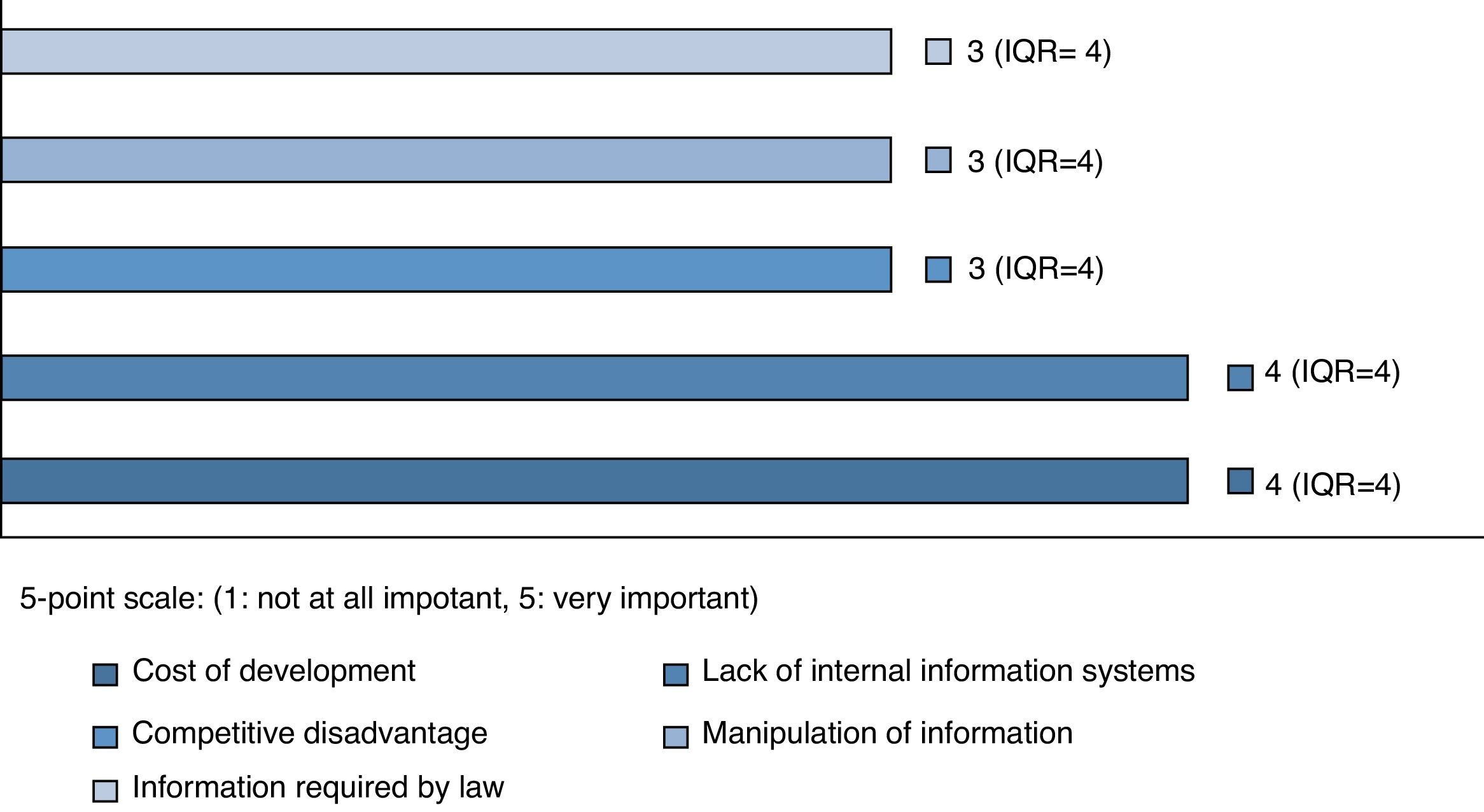

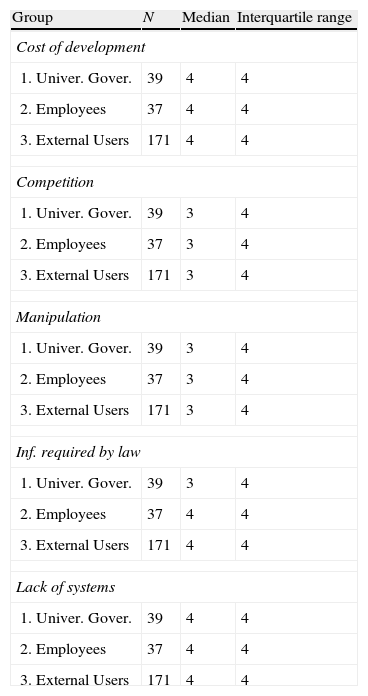

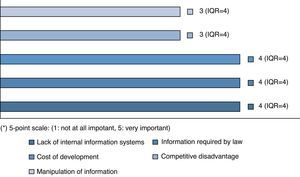

The results of our analysis show that respondents believe that the lack of internal information systems for measuring and identifying intangibles, the high/expensive cost of development and the fact that they are only required to disclosure information as required by law are the main reasons why universities do not disclose such information. The last positions correspond to the possibility of creating a competitive disadvantage for the university and of making room for the manipulation of information (see Fig. 3).

Thus, unlike other empirical studies such as those by Babío et al. (2003), Beattie and Thompson (2005), according to respondents, the factor that most influenced the decision to withhold information relating to intellectual capital (evidenced as a user demand) was the absence of internal information systems that identify and measure university intangibles. Contrary to belief, it was not the fear that competitors could use the information published by the university (median of 3 and interquartile range of 4). Obviously, if a university has not yet raised the issue of identifying and measuring intangible resources, then the disclosure of such resources is unlike.

However, given that these opinions may depend on the group studied, the perceived reasons will also be analyzed according to each of the groups identified.

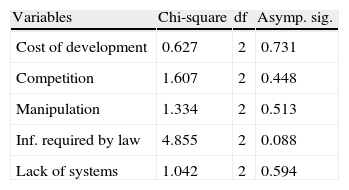

As pointed out by the Kruskal–Wallis test (Table 6), the differences between these three groups are not statistically significant for any of the analyzed reasons for nondisclosure (Sig.>0.05). So, it should be noted that the valuations given by different user groups are similar (see Table 7 which shows the analysis of the descriptive statistics for each of the groups analyzed).

Differences in perceptions of the reasons for not disclosing information on intellectual capital among user groups (Kruskal–Wallis test) (test statistics).a,b

| Variables | Chi-square | df | Asymp. sig. |

| Cost of development | 0.627 | 2 | 0.731 |

| Competition | 1.607 | 2 | 0.448 |

| Manipulation | 1.334 | 2 | 0.513 |

| Inf. required by law | 4.855 | 2 | 0.088 |

| Lack of systems | 1.042 | 2 | 0.594 |

Reasons not to publish information on intellectual capital by user groups (descriptive statistics).

| Group | N | Median | Interquartile range |

| Cost of development | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 4 | 4 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 4 | 4 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 4 | 4 |

| Competition | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 3 | 4 |

| Manipulation | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 3 | 4 |

| Inf. required by law | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 4 | 4 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 4 | 4 |

| Lack of systems | |||

| 1. Univer. Gover. | 39 | 4 | 4 |

| 2. Employees | 37 | 4 | 4 |

| 3. External Users | 171 | 4 | 4 |

5-Point scale (1 not at all important; 5: very important).

In the light of these results, we can conclude that all users (regardless of the group they belong to) value internal systems for identifying and measuring intangibles. Hence, the lack of such internal systems is the main reason for not disclosing information on intellectual capital. No such need has arisen before.

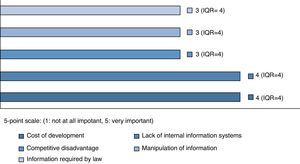

On the other hand, since university governance members are responsible for preparing the annual university accounts (or have a direct influence on its development), we shall discuss next in more detail their opinion about the reasons why universities do not disclose information on intellectual capital (see Fig. 4).

The absence of internal information systems to identify and measure a university's intangibilities has been pointed out by university governance members as being the main reason why universities do not disclose information on intellectual capital (74.4% note as being the main reason). In our opinion, the lack of these systems is mainly due to the fact that the need for them has not yet been proposed. In addition, the university governing body perceives that the preparation of further information to be legally required on these intangible elements involves extensive costs to some degree (59% gives a high valuation).

ConclusionsThe profound ongoing changes in European higher education institutions (the Bologna process; increasing global competition, the construction of European higher education research areas: change in university governance) are requiring major strategic changes in institutional communication systems. Universities must acquire a model of governance to strengthen institutional autonomy, but also with greater transparency toward society and greater control over the results. From our point of view, autonomy and accountability are two sides of the same coin. In this context, reporting on intellectual capital becomes crucial in the universities, mainly due to the fact that knowledge is the main output and input in these institutions.

In this scenario, it is necessary to expand the traditional communication of universities through the incorporation of information on intellectual capital (an Intellectual Capital Report), because universities are increasingly forced to rise their transparency and their level of accountability to its various stakeholders.

The implementation of an Intellectual Capital Report will definitely improve the information on intellectual values of universities to the broad public and will help university management to better manage its previously invisible intellectual capital.

In the presence and perception of benefits derived from the reporting of intellectual capital, it could be expected that universities will not be limited to the dissemination of those data required by the law. Rather, universities should choose to make public all the information on their intellectual capital. However, we must also take into account which ones can be the main reasons for not disclosing information on intellectual capital. Thus, as a result of this work, we can realize through the views of the Social Councils members the reasons why universities do not disclose information on intellectual capital in the current university model of accounting information, as well as the positive consequences that may result from such publication.

Results show that 89.1% reported to show a high interest in the disclosure of intellectual capital by Spanish public universities, considering that such disclosure would increase the relevance of the information contained in the current university financial statements.

The second objective of our study was to analyze perceptions of costs and benefits of disclosure of intellectual capital. The main reasons given for the non-disclosure of intellectual capital are, in order of importance, the following ones: (i) the lack of internal systems of identification and measurement of intangible elements; (ii) the high cost of development, and (iii) the fact that universities are only obliged to disclose the information established by law. In all these cases, over 50% of the scores were identified as being highly relevant. The factor that most influenced the decision to withhold information relating to intellectual capital (evidenced as a user demand) was the absence of internal information systems that identify and measure university intangibles. Hence, the lack of such internal systems is the main reason for not disclosing information on intellectual capital. The lack of these systems is mainly due to the fact that the need for them has not yet been proposed. Moreover, according to the results derived from the Kruskal–Wallis test performed, these perceptions were independent of the user group they represented, as the means obtained for both were very similar.

In addition, the university governing body perceives that the preparation of further information to be legally required on these intangible elements involves extensive costs to some degree.

As to the possible benefits derived from the existence of an intellectual capital disclosure policy, firstly, note the high value provided to the different benefits, which is again a proof of the huge interest and need for Spanish public universities to publish such information. Specifically, the benefits identified as most important were: increased transparency; enhancement of the long-term vision of the institution; increased user satisfaction, and improved university credibility, image and reputation of the University.

The obtained high score is an advantageous way to increase the transparency of university information (the 75.3% consider it to be very important), justifying the need to disclose information on intellectual capital as a necessary step to achieving a transparency of information, as established in the University Strategy 2015. Furthermore, this transparency of information acts in favor of increasing the user satisfaction, reinforcing the links between universities and the group to whom it is addressed. Strongly related to the above is the advantage of improving the universities’ credibility, image, and reputation.

The existence of statistically significant differences by type of user is also interesting to note. With the results obtained from the examination of descriptive statistics, and nonparametric tests (Kruskal–Wallis test), we generally conclude that employees and external users seem to perceive the existence of higher profits associated with the publication of information on intellectual capital. On the contrary, with the opinion of university governance, benefits are related to increased transparency; increased user satisfaction; improved long-term vision of the institution, and an increased confidence/trust of workers.

Finally, there are some remarkable limitations from the research that suggest future lines of analysis. One of the main limitations refers to the sample under study and the structure of the survey. Thus, the fact of exclusively analyzing members of the Social Councils in Spanish universities has led to groups of users that have not yet been analyzed (i.e. investors and suppliers of resources, media, etc.). Hence, it would be interesting in the future to expand the sample to a broader community of representation. On the other side, in future surveys, it would be interesting to alternate Likert scale questions with ordinal type questions where the respondent were required to choose between different items. Some other lines of future research derived directly from the results obtained in this study would be the following: (i) to know Spanish university disclosure practices of intellectual capital; (ii) proposal and validation of a standardized university report on intellectual capital that allows comparisons between universities, and (iii) to point out what components of intellectual capital are the main contributors to achieving the strategic objectives of the universities.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interests.

To date, various studies has been done by many researchers to examine the determinants of intellectual capital disclosure around the world such as Taliyang and Jusop (2011), Hidalgo et al. (2011), Bruggen (2009), White (2007), García-Meca, Parra, Larrán, and Martínez (2005) and many more.