Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is a chronic inflammatory condition interfering with daily activities, social integration, and school attendance in children because of pain and joint inflammation during disease flares. Online resources might help children with JIA improve their social interactions and enhance their knowledge about their disease and the available therapeutic strategies.

ObjectiveThis study aims to reveal the social issues encountered by teenagers prone to JIA and determine their perception of the impact of social media on their daily life.

Material and methodsWe conducted this study using inductive qualitative methods to describe the sociocultural perception and experience of adolescents with JIA aged between 8 and 16 years.

ResultsIndividual interviews were held with 22 adolescents diagnosed with JIA. Fifty-two percent felt like outcasts and rejected by their peers because of their illness. Most of the participants expressed a need for their friends to be informed about their JIA diagnosis. Twenty-two-point-seven percent stated that they played sports for more than 5h a week. A total of 31.8% found their physical performance was not affected by their disease. Ninety-seven of the participants confirmed that they use social media on average 3h a day. YouTube and Facebook were ranked respectively as the first and the second preferred platforms. Seventeen percent of the children viewed these platforms as positive and helpful in dealing with JIA, especially by taking their minds off the pain, dealing with the stress resulting from the lack of mobility, and facilitating interactions with others.

ConclusionSocial integration in children with JIA is still challenging. Social media is helpful in managing JIA and improving social interactions, and in gaining useful information.

La artritis idiopática juvenil (AIJ) es una enfermedad inflamatoria crónica que interfiere en las actividades diarias, la integración social y la asistencia a la escuela en los niños, debido al dolor y la inflamación de las articulaciones durante los brotes. Los recursos en línea podrían ayudar a los pacientes con AIJ a mejorar sus interacciones sociales y ampliar sus conocimientos sobre la condición y las estrategias terapéuticas disponibles.

ObjetivoRevelar los problemas sociales a los que se enfrentan los adolescentes con AIJ y determinar su percepción del impacto de las redes sociales en su vida diaria.

Materiales y métodosEste estudio utilizó métodos cualitativos inductivos para describir la percepción sociocultural y la experiencia de los adolescentes con AIJ de entre 8 y 16 años.

ResultadosSe realizaron entrevistas individuales a 22 adolescentes diagnosticados de AIJ. De estos, 52% se sentían marginados y rechazados por sus compañeros debido a su enfermedad. La mayoría expresaron la necesidad de que sus amigos estuvieran informados sobre su diagnóstico de AIJ. Alrededor de 22% afirmó practicar deporte más de 5 horas a la semana y 31,8% consideró que su rendimiento físico no se veía afectado por la enfermedad. Un total de 97% de los participantes confirmaron utilizar las redes sociales una media de 3 horas al día. YouTube y Facebook se situaron respectivamente como la primera y la segunda plataformas preferidas. De los niños, 17% consideraba que estas plataformas eran positivas y útiles para hacer frente a la AIJ, especialmente porque les permitían olvidarse del dolor, lidiar con el estrés derivado de la falta de movilidad y facilitar las interacciones sociales.

ConclusiónLa integración social de los niños con AIJ sigue siendo un reto. Las redes sociales son útiles para controlar la AIJ y mejorar las interacciones sociales, así como para obtener información útil.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA) is childhood's most common chronic rheumatic disease.1 It encompasses all forms of arthritis that begin before the age of 16 years, persist for more than 6 weeks, and are of unknown etiology. Recurrent arthritis is the hallmark of this disease, characterized by pain and loss of function, and is frequently accompanied by loss of energy.2,3 Even in the era of modern treatment with the improved outcome of biological therapies, many children with JIA still experience flares and difficulties to attend daily life activities.4,5 JIA-related symptoms have been associated with interference in the daily life of children and adolescents including their friendships, school attendance, and even their family life. Several studies focused on the disease's impact on quality of life but as far as know, little previous research has investigated the experience and the perception of the disease by the children and their surroundings.6,7 This day-to-day life is undeniably affected by the great accessibility to the internet and the progression of social media.8 To gain a deeper understanding of the point of view of children with JIA regarding social interaction, we conducted an inductive qualitative study. The qualitative study was adapted to better understand the interference of these children with social issues. We aimed to elicit the experiences of children with JIA during school and family life and their perspectives and expectations regarding online resources and social media.

Patients and methodsParticipantsInclusion criteria were: age from 8 to 16 years old, diagnosis of JIA was based on the International League of Associations for Rheumatology criteria (ILAR).9 We excluded patients with severe mental illness and cognitive problems defined as a clinically significant disturbance in an individual's cognition, emotional regulation, or behavior.10

According to previous studies we estimated that a sample of 22 children was optimal to conduct the interviews.11,12 A list was derived from the outpatient clinic agenda and eligible patients were contacted by phone by our team. To be eligible to participate in this study, a subject had to meet the following criteria: 1. Diagnosed with JIA according to the ILAR categories at least 6 months before the start of the study; 2. Between 8 and 16 years of age; 3. Informed consent by patient and parents as well.

Data collectionGender, age, age at diagnosis, JIA subtype, and the current level of education were noted and collected from the patient record.

Data analysisWe used an inductive qualitative approach with the individual interview. Informants were sampled per convenience with data saturation. No refusals were noted. The phone interview was semi-structured, allowing participants to freely express their opinions about the general topics in a dialogue. The trained pediatric rheumatologist phoned all participants.

The subjects and questions are summarized in Table 1. Interviews lasted from 35 to 50min. After phone recording, the verbatim was transcript and coded accordingly by the authors. Open coding of the dialogue transcripts was conducted by (SM). Transcripts were returned to participants for comment.

Agenda for the semi-structured interviews.

| Did the disease impact your friendships: alienating/getting closer to friends |

| Do you feel different from your friends? How? |

| Do you feel your friends/family understand your disease? |

| Do you feel supported and understood by friends/members of your family? |

| Do you feel treated the same as your siblings? If not, how? |

| Are/were there adjustments made to support you? |

| Did you fail at school at one point? If yes, was it related to your disease? |

| Do you participate in high-level physical activities? |

| Did the disease influence your physical activity performance and time? |

| Do you play sports for more than 3 hours/per week? |

| Do you play sports in school? Is it different from your friends/affected by JIA? |

| Did your doctor prevent/encourage you some sports? |

| Are you active on social media? |

| Which platform? |

| How much time/day? |

| What are you looking for mainly? |

| Do you find social media useful/helpful in your relationship to JIA? |

All authors reviewed the coding of the transcript consistently to increase internal consistency. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. We conducted debriefing sessions and reviewed transcription samples by all the team members to enhance the trustworthiness and triangulation analysis.

Ethical statementParental or legal guardian consent was required before patient inclusion. The study was approved by the local ethics committee. In all cases, parents of interested children and adolescents were informed about the purpose of the study and they consented to participation. Their privacy and confidentiality were guaranteed.

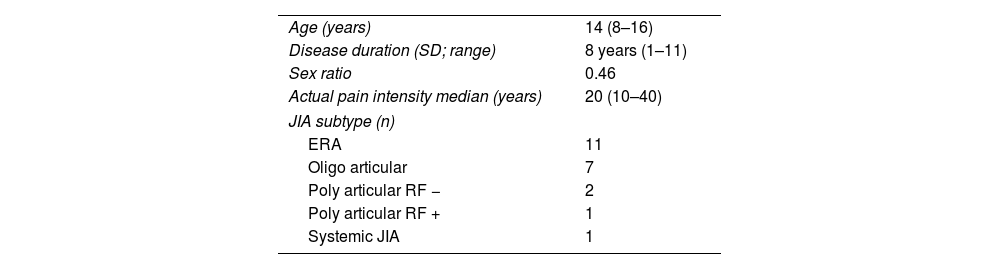

ResultsSample characteristicsA total of 22 patients were included in this study, 7 males and 15 females with a median age of 14 years (range 8–16). The patient characteristics are shown in Table 2.

Sociodemographic characteristics of JIA patients.

| Age (years) | 14 (8–16) |

| Disease duration (SD; range) | 8 years (1–11) |

| Sex ratio | 0.46 |

| Actual pain intensity median (years) | 20 (10–40) |

| JIA subtype (n) | |

| ERA | 11 |

| Oligo articular | 7 |

| Poly articular RF − | 2 |

| Poly articular RF + | 1 |

| Systemic JIA | 1 |

JIA: juvenile idiopathic arthritis; ERA: enthesitis-related arthritis.

The analysis focused on three key themes related to social life, physical activity, and social networks. Subthemes were found for each theme and are described in detail subsequently.

Social life: friendships and family lifeA pain topic emerged when we analyzed the discourse that patients “felt to be different fromothers”.

Seventeen patients felt understood and supported by their families in dealing with the different aspects of JIA. Six of them felt more spoiled than their other siblings, creating tension sometimes. As said by “…. my mother offered me everything I want, I’m the queen athome”

Ten patients felt different and not accepted by their peers because of the JIA. Some children made comments about feeling different from others because of JIA and feeling criticized by peers, including comments referring to criticism they have received as a consequence of JIA.

There were also comments about not feeling believed and understood about invisible symptoms such as pain or other symptoms. “…. I have a pain in my leg, it was difficult to be with friends and enjoy my time…I am still alone.”

Coping strategies were ignoring negative comments and maintaining activities with friends, despite feeling bad. When asked what they need to better manage their friendships, most of the participants expressed a need for their friends to be informed about the JIA diagnosis, its characteristics, course, impact, and consequences “…… I want to explain to them, but they laugh and look at me as if I’m doing a comedy back at home…”

Five children reported school absenteeism due to JIA (pain, being hospitalized) with a mean of 8 missed school days. Ten patients were fair in their schooling at some point. They thought it was related to the consequences of their disease. Only nine patients found the school staff to be helpful and supportive.

Physical activityThe adolescent suggested that “…. physical activity is the big problem….”. Only one participant was engaged in high-level sports and stated playing sports for more than 5h a week. Ten children did engage in a sports activity at school. Among these three engaged in all types of sports. Seven participants found their performance was not affected by their disease. Some of the participants found their performance limited because of pain (18%), hip involvement (9%), and functional limitations (18%). One patient had a heart condition limiting his physical activity as well. The majority found their symptoms worsen by playing sports, versus 7 children who found it got better. Only six stated having medical counseling from their doctor regarding physical activity. “….Although I have a sports exemption, I enjoy playing with my friends in sports activities….”

Online resources and social mediaOur participants confirmed that they’re using social media, for a mean of 3h per day. About their preferred network, they comment “… Ipreferred Facebook, there is a wide variety of video, photos, and comment…”

YouTube and Facebook came back as the first two preferred platforms: 82.6% and 69.6% respectively, followed by Instagram at 30.4%, Tiktok at 21.7, Snapchat at 17.4%, and WhatsApp at 8.7%. Other applications such as beReal which aims to share pictures with friends with no filter, enabling a more authentic social relationship, were not mentioned by the children. Children viewed these platforms as positive and helpful in dealing with JIA, especially taking their minds off the pain, dealing with the stress resulting from the lack of mobility, and facilitating interactions with others. “…. Tiktok enjoyed me, I can interact with friends, I laugh, I pass an amazing time…”

All of our participants were in favor of obtaining information about JIA, and interacting with others, including people with experience with the JIA through an online resource. “…..S…has also JIA, she is my virtual friend, ….”

Interestingly, none of the participants considered online resources as a place to interact with health professionals or have access to information about JIA.

DiscussionIn this study, we researched the experiences of children and adolescents with JIA about their families, and school life, as well as their perspectives and expectations regarding social media and online resources. Individual interviews were held with 22 adolescents diagnosed with JIA with different social, and educational backgrounds. The experiences of having JIA in families and at school show varying degrees of understanding and support as well as differences in adjustments that were provided. However, as we expected, the most talked-about physical activities’ limitation was pain and disability.13,14 Regular physical activities have an impact on muscular strength, physical and cardiovascular capacity, as well as psychosocial health.15 Although pain exacerbation, children choose to play in school activities to improve their friendship.16–18Children also expressed their feelings of being different, their fears of being criticized by peers, or not believing. These feelings have been mentioned in the studies reviewed.19–21 Some studies showed how children can be victims of bullying because of their disease.21

Participants also expressed their need to inform their friends and surroundings about their disease. They requested to be more understood by their peers and more acceptable.

These responses were online with some former studies in which patients need support in social life management.19,22

Adolescents are also users of the Internet, preferably using their smartphones, and mainly speaking with friends through social networks.

Unlike our study which showed a preference for YouTube and Facebook, other studies showed Instagram and WhatsApp to be the highest used apps among adolescents.23,24 Although their potential has been suggested for health, they have rarely been used in this direction. A recent study reviewed the literature about these two tools and found that WhatsApp has mainly been used in clinical decision-making and patient healthcare, and Instagram has been used for informative or motivational purposes.25 Despite this opportunity to facilitate the medical information, none of our participants use the online resource for this target. The main goal of Internet use was to have virtual friendships.

Our study has some limitations, furthermore the little sample of the interviewed patients, the study design not allows us to extrapolate our findings to all the JIA population. The qualitative research is heavily dependent on the individual skills of the researcher and more easily influenced by the researcher's personal biases.26 Unfortunately, it was difficult to use a focus group because of the covid-19 pandemic.

ConclusionsFamily and friends are central figures in children's and adolescents’ life and can represent an important support system to manage pain. The results of our study may be important to help researchers and health professionals to advance in the design of an efficient supporting system relying on these parties. As the experiences of patients affected by JIA during their school life, maybe comparable to the barriers they encounter in adult working life, having a strong supporting system from an early age is an essential step for JIA patients to become healthy productive adults. Finally, Online resources especially now with the emerging role of social media can be also helpful in managing JIA and improving social networks with friends, as well as getting helpful information.

Authors’ contributionsSM and FH wrote the manuscript; DBN edited the language; KM, DK and FM corrected the scientific data; WH approved the final manuscript.

Ethical approval and consent to participateYes.

Availability of supporting dataNA.

FundingNo.

Conflict of interestsNone.

None.