Gitelman syndrome is a renal tubule disease that involves hypokalaemic metabolic alkalosis, hypomagnesaemia and hypocalciuria. The musculoskeletal effects of Gitelman syndrome are common, including the development of chondrocalcinosis.

Clinical caseA female patient with long-standing chondrocalcinosis associated with chronic hypomagnesaemia on treatment with calcium and magnesium. After the suspension of the treatment due to surgery, she presented with a generalised weakness, metabolic alkalosis, hypokalaemia, hypomagnesaemia and hypocalciuria, with final diagnosis of Gitelman syndrome. After re-introducing the treatment, she improved clinically, with electrolytes remaining stable.

Discussion and conclusionsA proper diagnosis of this type of tubular diseases is essential because an adequate treatment avoids associated complications.

El síndrome de Gitelman es una tubulopatía caracterizada por alcalosis metabólica hipopotasémica, hipomagnesemia e hipocalciuria. Sus efectos musculoesqueléticos son comunes, pudiendo provocar desarrollo de condrocalcinosis.

Caso clínicoPaciente con condrocalcinosis de larga data asociada a hipomagnesemia crónica en tratamiento con calcio y magnesio. Tras la suspensión del tratamiento debido a una intervención quirúrgica presentó debilidad generalizada, alcalosis metabólica, hipopotasemia, hipomagnesemia e hipocalciuria con diagnóstico final de síndrome de Gitelman. Tras la instauración de tratamiento, mejoró clínica y analíticamente manteniendo cifras iónicas estables.

Discusión y conclusionsResulta fundamental un adecuado diagnóstico de este tipo de tubulopatías, ya que un tratamiento adecuado evita complicaciones asociadas.

Gitelman syndrome (GS) is an autosomal recessive tubulopathy due to SLC12A3 gene mutations which encodes for the thiazide-sensitive NaCl cotransporter, and is localized in the distal convoluted tubule.1 The estimated prevalence is 1:40.000.1 Biochemically, it is similar to Bartter syndrome,2 with comparable treatment characteristics using long-term thiazide diuretics: hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis, and reduced urinary calcium levels. This latter characteristic is the main differentiator between both syndromes.1,2 Although it is a hereditary disease, it is often diagnosed during adolescence or early adulthood.3 However, late presentations such as the clinical case herein discussed, frequently with chondrocalcinosis, are present in a significant number of cases.4

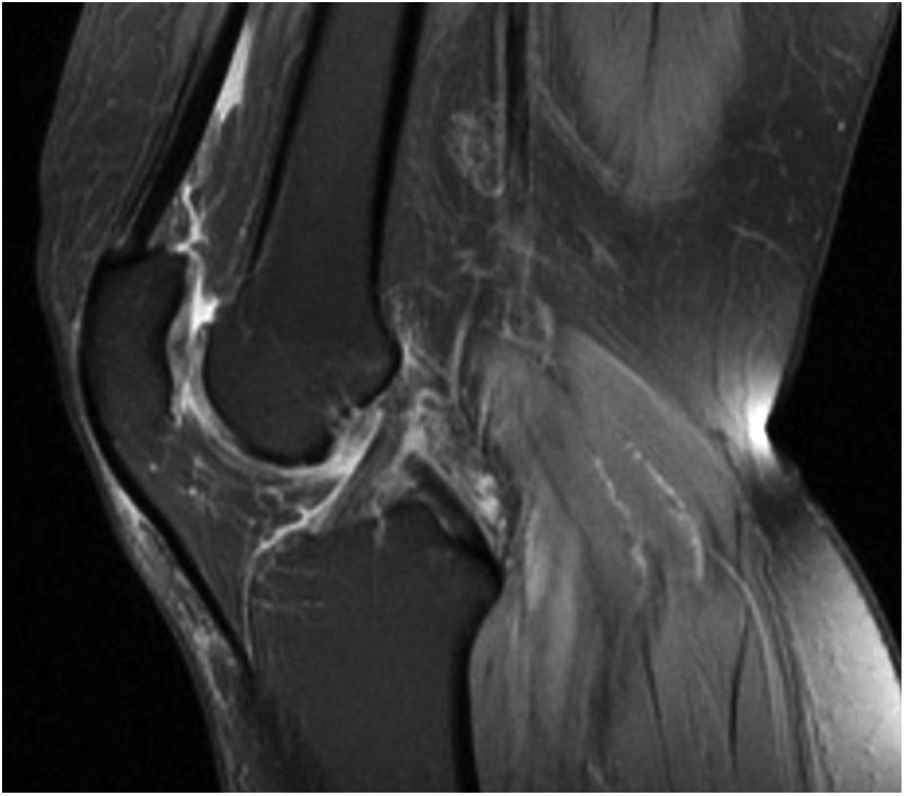

Clinical observationThis is a 60-year old female with a history of myopia magna, appendicectomy and chondrocalcinosis presenting as long-standing osteoarthritis, associated with hypomagnesemia which is being followed by rheumatology. Since her adolescent years, the patient complaint about joint weakness and discomfort that required rheumatological monitoring and was diagnosed with hypomagnesemia and left knee arthritic chondrocalcinosis (Fig. 1), which was treated with oral calcium and intermittent magnesium supplementation. Following an episode of choledocholithiasis, the patient underwent cholecystectomy, and she resumed partial therapy without magnesium supplementation after hospital discharge. After she was discharged, the patient returned to the emergency department due to generalized weakness, with no other associated symptoms; she was hemodynamically stable and her blood pressure was normal. The laboratory tests showed hypokalemia and hypomagnesemia. The treatment administered was unsuccessful and the patient was then admitted to nephrology for further studies and medication adjustments. Other relevant data include the presence of metabolic acidosis with a pH of 7.52 and bicarbonate of 29 mmol/L, potassium (K) 2.9 mEq/L, magnesium (Mg) 1.03 mg/dl, calcium 9.9 mg/dl, and a normal CBC. The isolated urine sample showed hypocalciuria with a calcium level of 2 mg/dl, chlorine 45 mEq/l, and no albuminuria.

The abdominal ultrasound showed normal kidneys. Intravenous magnesium and potassium supplementation was initiated and switched over to oral administration after the values became normal. Once the medications were adjusted, the patient was discharged with oral treatment including indomethacin 25 mg/24 h, potassium ascorbate (25 mEq of K per tablet) every 8 hours, and magnesium (200 mg of magnesium) every 8 hours. The control laboratories showed the following results: PH 7.42, bicarbonate 26 mmol/L, K 4 mEq/L, Mg 1.88 mg/dl.

DiscussionSG is an autosomal recessive disfunction with overlapping manifestations to Bartter syndrome, including hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, hyperreninemia, juxtaglomerular apparatus hyperplasia and hyperaldosteronism. Some patients also exhibit hypomagnesemia or high levels of prostaglandin E2.1

Bartter syndrome or GS are usually suspected in patients with unexplained hypokalemia, metabolic alkalosis, and normal to low blood pressure. Other causes for electrolyte disorders should be ruled out in these patients, for instance GI bleeding or diuretic therapy.1 GS is more common than Bartter syndrome, and is usually diagnosed in adulthood because of its more benign course.2 The major difference with Bartter syndrome is urinary calcium excretion which is elevated or normal in Bartter syndrome and decreased in GS.2 Therefore, our patient was finally diagnosed with GS. Additionally, one of the associated manifestations is chondrocalcinosis, which was present in the clinical case discussed; it is usually due to associated chronic and severe hypomagnesemia.5 Chondrocalcinosis may cause swollen, hot and tender joints, usually involving the knees.5 Additionally, patients with GS may experience weakness, tetany, cramps, or fatigue which may significantly affect their quality of life.6 With regards to treatment, tubular defects cannot be corrected (except through kidney transplant).3 Therefore, the treatment must be maintained for life, and is aimed at minimizing the effects of secondary renin, aldosterone, and prostaglandin elevations, and correcting any electrolyte imbalances. NSAIDs and any distal tubule sodium-potassium exchange blockers may be effective in some patients with GS, as well as potassium and magnesium supplements.3

ConclusionsThe objective of this case discussion is to emphasize the importance of diagnosing tubulopathies in rheumatoid patients with electrolyte disorders that may be initially dormant, but in the long-term may lead to the type of clinical joint pathology herein discussed.

The GS described presents typical electrolyte imbalances with hypokalemic metabolic alkalosis, hypomagnesemia, and hypocalciuria, further complicated with knee chondrocalcinosis. Recognizing this type of tubulopathy and offering treatment targeted to correct the electrolyte imbalances is essential and should be subject to regular monitoring, in order to improve the patient’s quality of life and avoid any associated complications.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Please cite this article as: Hernández García E, Torres Sánchez MJ. Diagnóstico de síndrome de Gitelman en paciente con condrocalcinosis. Rev Colomb Reumatol. 2020;27:202–204.