To determine the psychiatric diagnoses and treatments of patients admitted to the high-risk obstetric service who underwent a consultation with a liaison psychiatrist.

MethodsA descriptive observational study that included pregnant women from the high-risk obstetric service of a highly specialised clinic in Medellín, who had a liaison psychiatry consultation between 2013 and 2017. The main variables of interest were psychiatric and obstetric diagnoses and treatments, in addition to biopsychosocial risk factors.

ResultsA total of 361 medical records were screened, with 248 patients meeting the inclusion criteria. The main prevailing psychiatric diagnosis was major depressive disorder (29%), followed by adaptive disorder (21.8%) and anxiety disorders (12.5%). The pharmacologic treatments most used by the psychiatry service were SSRI antidepressants (24.2%), trazodone (6.8%) and benzodiazepines (5.2%). The most common primary obstetric diagnosis was spontaneous delivery (46.4%), and the predominant secondary obstetric diagnoses were hypertensive disorder associated with pregnancy (10.4%), gestational diabetes (9.2%) and recurrent abortions (6.4%). Overall, 71.8% of the patients had a high biopsychosocial risk.

ConclusionsThe studied population's primary psychiatric disorders were major depressive disorder, adjustment disorder and anxiety disorders, which implies the importance of timely recognition of the symptoms of these perinatal mental pathologies, together with obstetric and social risks, in the prenatal consultation. Psychiatric intervention should be encouraged considering the negative implications of high biopsychosocial risk in both mothers and children.

Determinar los diagnósticos psiquiátricos y describir características clínicas, el riesgo biopsicosocial y los tratamientos de las pacientes hospitalizadas en el servicio de alto riesgo obstétrico para las que se realizó una interconsulta con psiquiatría.

MétodosEstudio observacional descriptivo en el que se incluyó a las pacientes del servicio de alto riesgo obstétrico de una institución de alta complejidad de Medellín para las que se interconsultó por psiquiatría de enlace entre 2013 y 2017. Las principales variables de interés fueron los diagnósticos y tratamientos tanto psiquiátricos como ginecoobstétricos, además de los factores de riesgo obstétricos y psicosociales.

ResultadosSe cribaron en total 361 historias clínicas, y 248 pacientes cumplían los criterios de inclusión. El diagnóstico psiquiátrico principal más prevalente fue trastorno depresivo mayor (29%), seguido por el trastorno de adaptación (21,8%) y los trastornos de ansiedad (12,5%); los fármacos más prescritos por psiquiatría fueron antidepresivos ISRS (24,2%), trazodona (6,8%) y benzodiacepinas (5,2%). El diagnóstico obstétrico principal más común fue el parto espontáneo (46,4%) y los diagnósticos obstétricos secundarios que predominaron fueron trastorno hipertensivo asociado con el embarazo (10,4%), diabetes gestacional (9,2%) y abortos recurrentes (6,4%). El 71,8% de las pacientes tenían un riesgo biopsicosocial alto.

ConclusionesLos principales diagnósticos psiquiátricos fueron trastorno depresivo mayor, trastorno de adaptación y trastornos de ansiedad, lo que implica la importancia del oportuno reconocimiento en la evaluación prenatal de los síntomas de estas entidades, conjuntamente con los factores de riesgo obstétrico y social. La intervención psiquiátrica es necesaria considerando las implicaciones negativas que tiene el alto riesgo tanto para la madre como para el niño.

Pregnancy is considered a stressful physiological event that sometimes causes the recurrence or exacerbation of coexisting maternal mental disorders, or the onset of a new disorder, associated with obstetric complications and poor prognosis for the infant, and psychiatric risks in the postpartum period.1

How psychiatric illness in the pregnant mother can affect obstetric outcome, and in different ways, the foetus and newborn, has been widely studied. Various publications report a significant correlation between maternal mental health conditions prior to conception and obstetric complications, perinatal foetal death, low Apgar scores, low birth weight and congenital malformations.2,3 A high risk of complications, such as gestational hypertension, antepartum haemorrhage, as well as premature labour and birth, associated with a maternal history of depression, bipolar disorder (BD), post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and adjustment disorder, among other psychiatric illnesses,4 has also been reported.

Reviews, like the one by Hoirisch-Clapauch et al.,5 show that anxiety disorders, eating disorders, PTSD, and unipolar or bipolar depression during pregnancy result in a high risk of premature birth, low birth weight and of the length of the newborn being small for gestational age. Such reviews also show that schizophrenic women have a higher risk of miscarriage, with a 72% chance of thromboembolic disease. Yonkers et al.6 demonstrated that, for each point increase on the Modified PTSD Symptom Scale, the risk of preterm birth increases by 1–2%.

Several studies confirm that perinatal anxiety compromises the child's development in different areas. It has been found that pregnant women with high levels of anxiety were two to three times more likely to give birth to children who scored more than two standard deviations above the mean for emotional and behavioural problems7 or presented with problems with verbal communication at 3 years of age.8 In one prospective study, Mughal et al.9 demonstrated that, according to reports from mothers with anxiety, depression or symptoms of perinatal stress, their children, at 3 years of age, were at risk of delays in fine motor development (15.4%), gross motor skill development (12.7%), cognitive problem-solving (11.2%), socialisation (5.6%) and communication (5.2%). Furthermore, perinatal depression has been associated with a negative impact on the child's cognitive and emotional development, with language delays and behavioural issues.10,11

There is a general consensus on the benefits of prenatal care, and health facilities and the medical community have implemented guidelines that recommend screening for prevalent psychiatric illnesses, such as prenatal depression and anxiety. In Colombia, these are included in the Guidelines of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection for the prevention, early detection and treatment of pregnancy complications,12 and, in the United States, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends screening for depression at prenatal check-ups.13 However, the treatment of mental health conditions in pregnant women is not always optimal. Marcus et al.14 detected that 20% of women screened as part of their prenatal care at ten American obstetric clinics reported significant depressive symptoms, but despite this, 86% did not receive any type of medications, psychotherapy or counselling, and routine monitoring for depression was non-existent. For their part, in a review on the prevalence and incidence of perinatal depression, Woody et al.15 highlighted the low levels of screening and treatment of this condition.

High obstetric risk (HOR) is considered to occur when the possibility of serious complications, for both the woman and her foetus or newborn, is greater than the risk experienced incidentally by the general population; and, therefore, the biological, genetic, environmental, psychological, social, economic and cultural factors that influence the likelihood of these complications arising, must be screened for and treated in order to reduce the likelihood of any harm occurring.16 It has been established that psychiatric and medical comorbidities, and chronic diseases suffered by the mother that are related to perinatal adverse outcomes should be screened for in prenatal care, along with psychological and sociocultural factors, grouped together as psychosocial factors.4,17–19

The majority of information on psychiatric illness in obstetric patients comes from publications assessing obstetric risk. The prevalence of depressive disorders varies between 17.8% and 33%,3,4,20,21 while the prevalence of BD has been reported to be 10.3%,4 and it has been estimated that 25–30% of bipolar women who become pregnant suffer a depressive or manic episode during pregnancy or the postpartum period.20 Other prevalences reported in deliveries at hospitals are 21% for anxiety, 11% for schizophrenia and 3% for neuroses,3 or 16.3% for substance abuse, 2.7% for PTSD and 30% for different affective disorders.4 The prevalence figures for adjustment disorder vary between 8.3% and 87%.4,21,22

In Latin America, a prevalence of 33.6% has been reported for depressive and anxiety disorders in Brazilian pregnant women receiving prenatal care.23 In Colombia, however, Peinado-Valencia et al.24 found a prevalence of 31.5% for prenatal depressive symptoms in Cartagena, and Ricardo-Ramírez et al.25 detected a prevalence of 61.4% screening positive for depression and 40.7% for anxiety in inpatient and outpatient HOR pregnant women at a private clinic in Medellín. Of all the aforementioned studies, the last study is the only one to have been conducted in HOR patients.

It is important to note that perinatal depression refers to depression that occurs during pregnancy as well as depression occurring during the first four weeks after childbirth, according to the DSM-5. It thus meets the criteria for a major depressive episode, and is generally of complex and multifactorial aetiology with prevalences ranging between 3% and 11.9%. The highest prevalence is in pregnant women from low- and middle-income countries.15,26 It is estimated that suicide is the fifth most common cause of death during the perinatal period in the United States27 and it has been recognised that at least 90% of those who commit suicide had a psychiatric diagnosis at the time of their death, with depression, substance abuse and psychotic disorders being the most prevalent.28,29

Due to the importance of mental illness in pregnant women and the maternal-foetal repercussions, this study was conducted with a focus on psychiatric illness of a pregnant population with HOR.

The objectives of the study are to determine the psychiatric diagnoses of pregnant patients admitted to the high-risk obstetric service of a highly specialised university clinic, who were referred by liaison psychiatry, and to simultaneously describe the clinical characteristics, biopsychosocial risk factors and treatments prescribed.

MethodsStudy and sample typeA retrospective observational study was conducted in a cohort of pregnant patients who were admitted to the high-risk obstetric service of Clínica Universitaria Bolivariana between 2013 and 2017, who were referred by liaison psychiatry. It included all patients of any age screened by the group of liaison psychiatrists at the request of the treating obstetricians-gynaecologists during the aforementioned period, and excluded those patients whose medical records were incomplete (missing information), who did not have a diagnosis or complete assessment by liaison psychiatry, or who did not have a diagnosis coded by obstetrics and gynaecology.

ToolsA data collection tool was designed and, before starting the study, a pilot test was performed in which ten medical records of patients who met the inclusion criteria were assessed. The aim was to adjust the data collection tool and standardise the process. The tool recorded the sociodemographic information of the pregnant women, their psychiatric and obstetric diagnoses and treatments, as well as the Prenatal Biopsychosocial Risk Assessment scale by Herrera et al.30 with its respective variables from the following three categories: reproductive history, current pregnancy and psychosocial risk.

For psychiatric diagnoses, the diagnostic criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), were used, and for obstetric diagnoses, the International Classification of Diseases, tenth edition (ICD-10), was used.26,31 The main psychiatric diagnosis was considered to be the one coded when the liaison psychiatrist first assessed the patient. Comorbid mental disorders, that is, disorders accompanying the main psychiatric diagnosis, were considered as secondary diagnoses. The diagnosis established by the obstetrician-gynaecologist when the patient was admitted to the obstetrics and gynaecology department (including diagnoses such as spontaneous labour or monitoring of a high-risk pregnancy) was considered to be the main obstetric diagnosis, while other diagnoses recorded in the patients' medical record that refer to the main obstetric-gynaecological diagnosis that led to the hospital admission, such as pregnancy-associated hypertension, gestational diabetes or premature rupture of membranes, were considered secondary obstetric diagnoses. Organic diagnoses accompanying the gynaecological-obstetric disease (urinary tract infection, anaemia, thyroid disease, etc.) were considered as comorbidities.

To determine the obstetric and psychosocial risk factors of what was recorded in the patients' medical records, the Prenatal Biopsychosocial Risk Assessment scale was used,30 a scale that was implemented with the prior authorisation of the authors for use in this study. This scale consists of a questionnaire developed for Colombia and evaluated in various cultures. It consists of 3 categories. The first concerns reproductive history, which has 11 variables: age split into groups, parity, previous caesarean sections, history of pre-eclampsia or hypertension, recurrent spontaneous abortions or infertility, postpartum haemorrhage or manual removal of placenta, birth weights of previous newborns, history of late foetal deaths or early neonatal deaths, abnormal or difficult labour, and gynaecological surgeries. The second category concerns the current pregnancy, with 11 variables, including chronic kidney disease, gestational diabetes and pregestational diabetes, bleeding and other obstetric complications of the pregnancy. The third category looks at psychosocial aspects, with 2 variables: severe anxiety and inadequate social-family support. Severe anxiety corresponds to the presence of symptoms of emotional distress (e.g. hyperventilation, fear, inability to relax, tendency to cry, motor restlessness), depressive mood (anhedonia, apathy, dysthymia, insomnia, emotional lability) and/or neurovegetative symptoms (pallor, sweating, dizziness, dry mouth, tension headache). Inadequate social-family support implies dissatisfaction with support received from the family and/or partner during pregnancy and is related to shared time, space and money. The first two categories correspond to the biomedical scale, and the third corresponds to the psychosocial scale. The combination of these two scales makes up the biopsychosocial assessment.

Each of the 29 variables of the Prenatal Biopsychosocial Risk Assessment scale has a specific score, ranging from 0 to 3, and is previously assigned by the authors of the scale, taking into account the severity of each variable. Information regarding each item was obtained from the data recorded in the medical records of each of the pregnant women being assessed. The sum of the scores of all the variables for each patient gives the biopsychosocial risk, which can be high risk (≥3 points), low risk (1–2 points) and no risk (0 points).

Regarding the qualification of the third category of the Prenatal Biopsychosocial Risk Assessment scale, we can see that scoring 1 for severe anxiety requires the presence of at least 2 of its 3 components (emotional distress, depressive mood and neurovegetative symptoms), and a score of 1 for inadequate social-family support requires the presence of 2 of its 3 components (shared time, space and money).

ProceduresAll of the medical records were reviewed of the pregnant patients admitted to the high-risk obstetric service of the clinic between 1 January 2013 and 31 December 2017, who had been referred by liaison psychiatry, and the sociodemographic information, psychiatric and obstetric diagnoses and treatments, as well as the Prenatal Biopsychosocial Risk Assessment score, were recorded in the data collection tool. The main diagnoses of both specialties were then analysed, and any secondary psychiatric diagnoses, and any secondary or ancillary obstetric diagnoses and obstetric comorbidities were taken into account.

The data collection stage consisted of the extracting the data and subsequently all the information was compiled and standardised in a database for analysis.

The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana.

Data analysisThe information was stored in Excel® and the data were analysed using this software tool and SPSS® 21.0. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to test normality of age. As age was not normally distributed, it was presented as its median [interquartile range]. Categorical variables were reported as absolute frequencies and percentages.

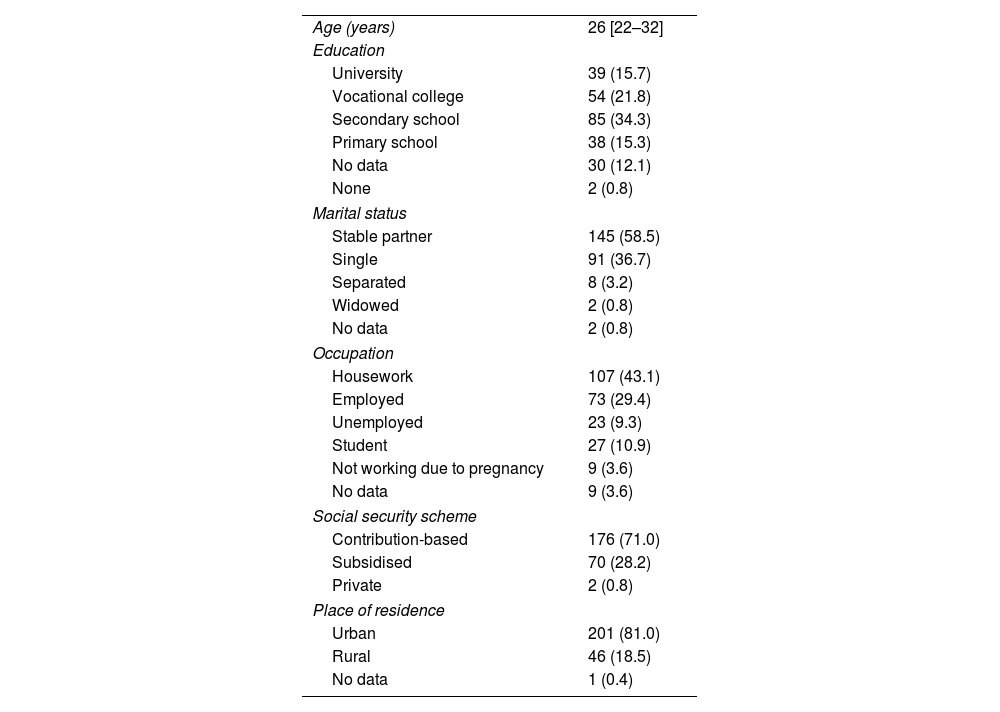

ResultsOf a total of 31,429 pregnant women attended to during the study's reference period, 361 medical records of mothers who had been referred by liaison psychiatry were initially reviewed. Of these, 93 were repeat episodes (during the same hospital admission or during different hospitalisations of the same patient during the same pregnancy) and 20 corresponded to medical records with at least one exclusion criteria. As a result, 248 patients met the criteria for the analysis and were included in the study. The median age was 26 years (interquartile range 22–32 years). Other notable sociodemographic characteristics of the sample included: having a stable partner in just over half of the sample, being a housewife in 43.1%, and registered in the contribution-based social security scheme and having an urban place of residence, with figures above 71% (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the 248 patients included in the study.

| Age (years) | 26 [22–32] |

| Education | |

| University | 39 (15.7) |

| Vocational college | 54 (21.8) |

| Secondary school | 85 (34.3) |

| Primary school | 38 (15.3) |

| No data | 30 (12.1) |

| None | 2 (0.8) |

| Marital status | |

| Stable partner | 145 (58.5) |

| Single | 91 (36.7) |

| Separated | 8 (3.2) |

| Widowed | 2 (0.8) |

| No data | 2 (0.8) |

| Occupation | |

| Housework | 107 (43.1) |

| Employed | 73 (29.4) |

| Unemployed | 23 (9.3) |

| Student | 27 (10.9) |

| Not working due to pregnancy | 9 (3.6) |

| No data | 9 (3.6) |

| Social security scheme | |

| Contribution-based | 176 (71.0) |

| Subsidised | 70 (28.2) |

| Private | 2 (0.8) |

| Place of residence | |

| Urban | 201 (81.0) |

| Rural | 46 (18.5) |

| No data | 1 (0.4) |

Values are expressed as n (%) or median [interquartile range].

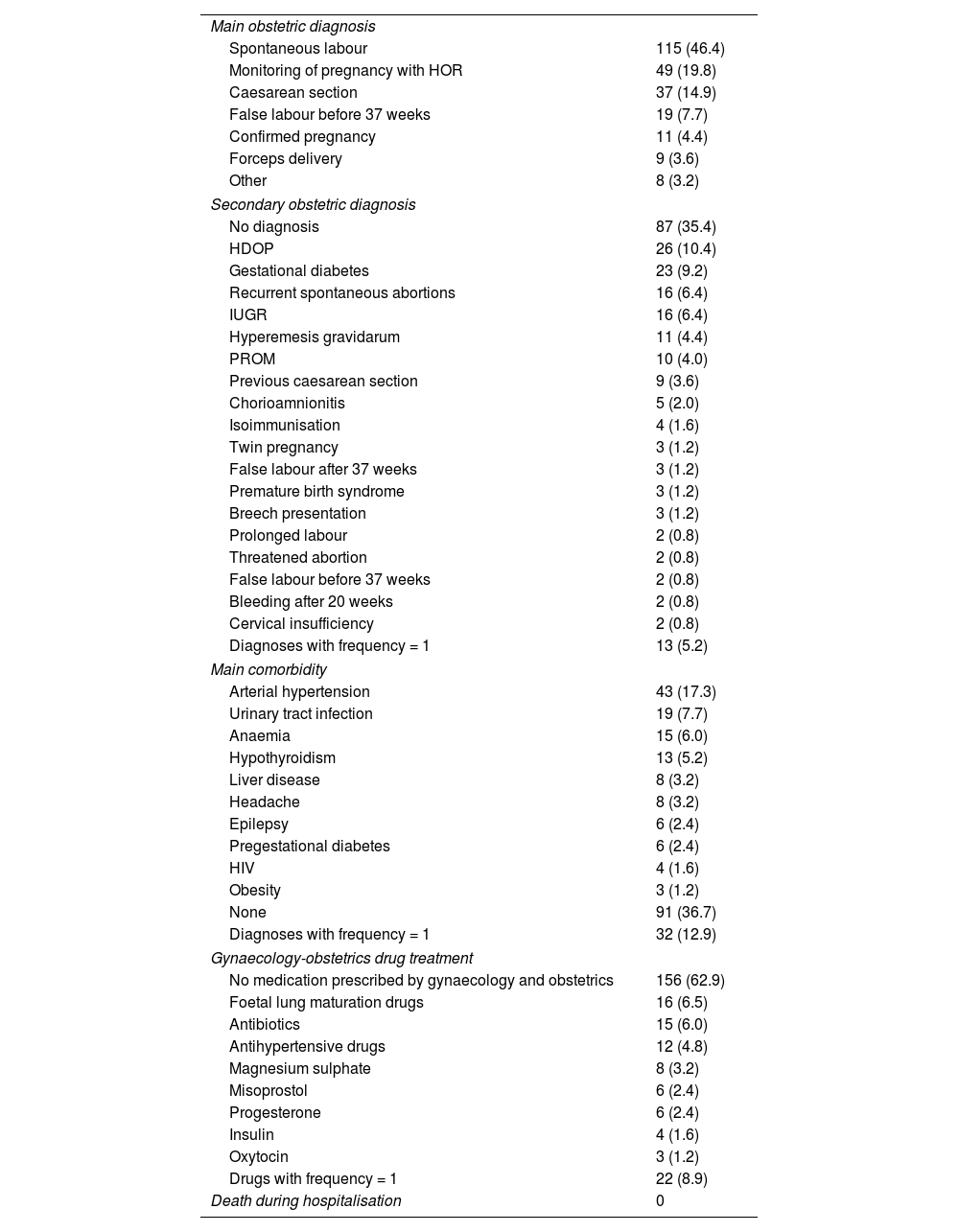

Table 2 shows the clinical obstetric variables. The three main obstetric diagnoses with highest prevalence were spontaneous labour (almost half of the mothers), monitoring of high-risk pregnancy in 19.8%, and caesarean section (14.9%). Regarding secondary obstetric diagnoses, just over a third of the pregnant women had none, and the most prevalent secondary obstetric diagnoses were pregnancy-associated hypertension and gestational diabetes. The main obstetric comorbidity was hypertension and 36.75% of the patients did not have any comorbidity. The main drug treatments used by obstetrics were foetal lung maturation drugs, antibiotics and anti-hypertensive drugs. More than half of the patients did not receive any drug treatment. Furthermore, there were no deaths during hospitalisation among the study sample.

Obstetric clinical variables of the 248 patients.

| Main obstetric diagnosis | |

| Spontaneous labour | 115 (46.4) |

| Monitoring of pregnancy with HOR | 49 (19.8) |

| Caesarean section | 37 (14.9) |

| False labour before 37 weeks | 19 (7.7) |

| Confirmed pregnancy | 11 (4.4) |

| Forceps delivery | 9 (3.6) |

| Other | 8 (3.2) |

| Secondary obstetric diagnosis | |

| No diagnosis | 87 (35.4) |

| HDOP | 26 (10.4) |

| Gestational diabetes | 23 (9.2) |

| Recurrent spontaneous abortions | 16 (6.4) |

| IUGR | 16 (6.4) |

| Hyperemesis gravidarum | 11 (4.4) |

| PROM | 10 (4.0) |

| Previous caesarean section | 9 (3.6) |

| Chorioamnionitis | 5 (2.0) |

| Isoimmunisation | 4 (1.6) |

| Twin pregnancy | 3 (1.2) |

| False labour after 37 weeks | 3 (1.2) |

| Premature birth syndrome | 3 (1.2) |

| Breech presentation | 3 (1.2) |

| Prolonged labour | 2 (0.8) |

| Threatened abortion | 2 (0.8) |

| False labour before 37 weeks | 2 (0.8) |

| Bleeding after 20 weeks | 2 (0.8) |

| Cervical insufficiency | 2 (0.8) |

| Diagnoses with frequency = 1 | 13 (5.2) |

| Main comorbidity | |

| Arterial hypertension | 43 (17.3) |

| Urinary tract infection | 19 (7.7) |

| Anaemia | 15 (6.0) |

| Hypothyroidism | 13 (5.2) |

| Liver disease | 8 (3.2) |

| Headache | 8 (3.2) |

| Epilepsy | 6 (2.4) |

| Pregestational diabetes | 6 (2.4) |

| HIV | 4 (1.6) |

| Obesity | 3 (1.2) |

| None | 91 (36.7) |

| Diagnoses with frequency = 1 | 32 (12.9) |

| Gynaecology-obstetrics drug treatment | |

| No medication prescribed by gynaecology and obstetrics | 156 (62.9) |

| Foetal lung maturation drugs | 16 (6.5) |

| Antibiotics | 15 (6.0) |

| Antihypertensive drugs | 12 (4.8) |

| Magnesium sulphate | 8 (3.2) |

| Misoprostol | 6 (2.4) |

| Progesterone | 6 (2.4) |

| Insulin | 4 (1.6) |

| Oxytocin | 3 (1.2) |

| Drugs with frequency = 1 | 22 (8.9) |

| Death during hospitalisation | 0 |

HOR: high obstetric risk; IUGR: intrauterine growth restriction; PROM: premature rupture of membranes; HDOP: hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Figures are expressed as n (%).

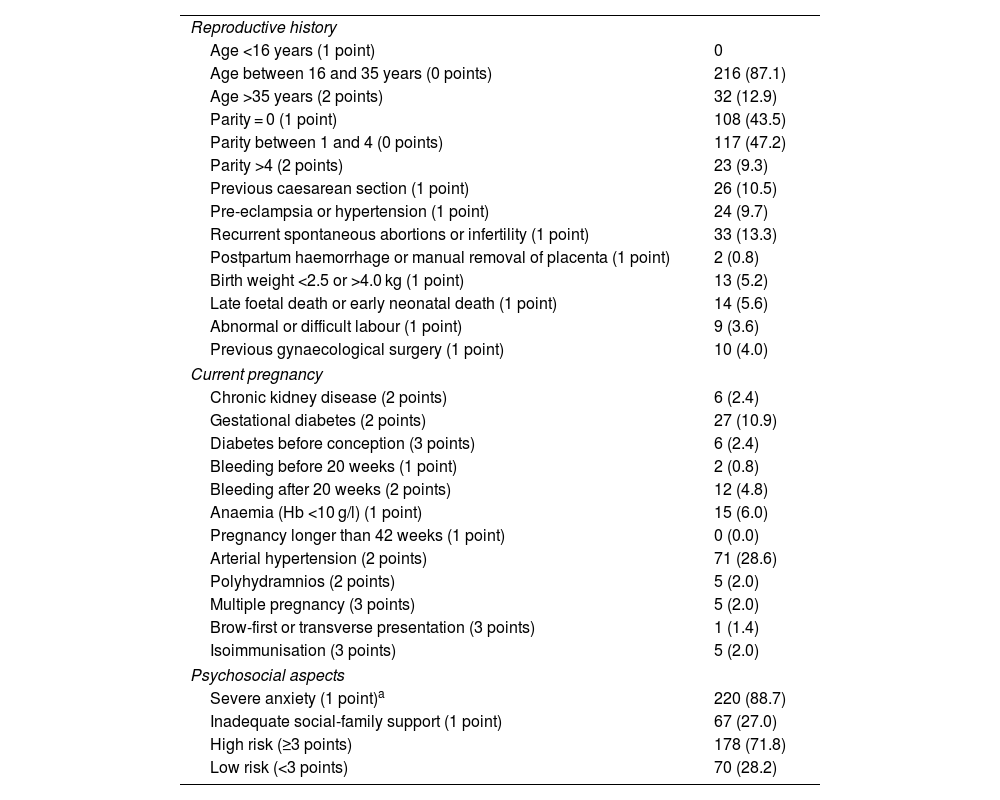

Obstetric risk factors were determined using the Prenatal Biopsychosocial Risk Assessment scale (Table 3). According to the scale, with regards to reproductive history, most of the patients in the sample aged between 16 and 35 years were in the no risk band (87.1%). Also, a parity of between 1 and 4 children was the most common history with a no risk score, conferring it with a protective factor. The highest risk was being nulliparous (43.5% of the patients) or having parity >4 (almost 10% of the patients). On considering the other reproductive variables, a history of recurrent spontaneous abortions or infertility, previous caesarean sections and pre-eclampsia stand out, in descending order.

Biopsychosocial risk factors and classification of perinatal risk according to the PBRA.

| Reproductive history | |

| Age <16 years (1 point) | 0 |

| Age between 16 and 35 years (0 points) | 216 (87.1) |

| Age >35 years (2 points) | 32 (12.9) |

| Parity = 0 (1 point) | 108 (43.5) |

| Parity between 1 and 4 (0 points) | 117 (47.2) |

| Parity >4 (2 points) | 23 (9.3) |

| Previous caesarean section (1 point) | 26 (10.5) |

| Pre-eclampsia or hypertension (1 point) | 24 (9.7) |

| Recurrent spontaneous abortions or infertility (1 point) | 33 (13.3) |

| Postpartum haemorrhage or manual removal of placenta (1 point) | 2 (0.8) |

| Birth weight <2.5 or >4.0 kg (1 point) | 13 (5.2) |

| Late foetal death or early neonatal death (1 point) | 14 (5.6) |

| Abnormal or difficult labour (1 point) | 9 (3.6) |

| Previous gynaecological surgery (1 point) | 10 (4.0) |

| Current pregnancy | |

| Chronic kidney disease (2 points) | 6 (2.4) |

| Gestational diabetes (2 points) | 27 (10.9) |

| Diabetes before conception (3 points) | 6 (2.4) |

| Bleeding before 20 weeks (1 point) | 2 (0.8) |

| Bleeding after 20 weeks (2 points) | 12 (4.8) |

| Anaemia (Hb <10 g/l) (1 point) | 15 (6.0) |

| Pregnancy longer than 42 weeks (1 point) | 0 (0.0) |

| Arterial hypertension (2 points) | 71 (28.6) |

| Polyhydramnios (2 points) | 5 (2.0) |

| Multiple pregnancy (3 points) | 5 (2.0) |

| Brow-first or transverse presentation (3 points) | 1 (1.4) |

| Isoimmunisation (3 points) | 5 (2.0) |

| Psychosocial aspects | |

| Severe anxiety (1 point)a | 220 (88.7) |

| Inadequate social-family support (1 point) | 67 (27.0) |

| High risk (≥3 points) | 178 (71.8) |

| Low risk (<3 points) | 70 (28.2) |

PBRA: Prenatal Biopsychosocial Risk Assessment scale by Herrera et al.

Values are expressed as n (%). The score pre-established by the authors of the PBRA for "yes" answers is shown in parentheses.

In the current pregnancy section of the same scale, just over a quarter of the patients had hypertension and around 10% had gestational diabetes, diagnoses that scored 2 on the perinatal risk scale. In the category of psychosocial aspects, a high prevalence (almost 90%) of the severe anxiety variable (corresponding to symptoms of emotional distress, depressive mood and/or neurovegetative symptoms) was found, and more than a quarter of the sample reported inadequate social-family support.

Finally, the sum of the scores for each variable of the scale revealed a high risk (3 or more points) for the vast majority of the pregnant women analysed.

Table 4 shows liaison psychiatry diagnoses made according to the DSM-5 and the treatments. The first main diagnosis was major depressive disorder (MDD), followed by adjustment disorder and anxiety disorders, which affect 63.3% of the sample. Some 75% of the patients did not have an active secondary psychiatric diagnosis or psychiatric comorbidity. The most common was substance use disorder, at 10.1%. A significant number of patients were found to have two or more psychiatric diagnoses (23.8%). Although almost half of the patients did not receive any psychopharmacological treatment, the drugs most prescribed by psychiatry were SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) antidepressants, the atypical antidepressant trazodone, and benzodiazepines. For 14.5% of the patients in the sample, the psychotropic drug they were taking upon admission to the high-risk obstetric service was stopped.

Liaison psychiatry diagnoses and treatments.

| Main diagnosis according to the DSM-5 | |

| Major depressive disorder | 72 (29.0) |

| Adjustment disorder | 54 (21.8) |

| Anxiety disorders | 31 (12.5) |

| Bipolar disorder | 21 (8.5) |

| Substance use disorder | 18 (7.3) |

| Personality disorder | 15 (6.0) |

| Mental disorder discarded | 7 (2.8) |

| Cases with less common diagnoses | 30 (12.1) |

| Active secondary diagnosis according to the DSM-5 | |

| None | 189 (76.2) |

| Substance use disorder | 25 (10.1) |

| Personality disorder | 12 (4.8) |

| Depressive disorder | 9 (3.6) |

| Cases with less common diagnoses | 13 (5.2) |

| Two or more psychiatric diagnoses | 58 (23.4) |

| Three or more psychiatric diagnoses | 52 (21.0) |

| Main drug treatment | |

| None | 116 (46.8) |

| SSRI | 60 (24.2) |

| Trazodone | 17 (6.8) |

| Benzodiazepine | 13 (5.2) |

| Mood stabiliser | 12 (4.8) |

| Atypical antipsychotic | 10 (4.0) |

| Typical antipsychotic | 7 (2.8) |

| SNRI | 6 (2.4) |

| Other | 7 (2.8) |

| A psychotropic drug she was taking was stopped | 36 (14.5) |

DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, SNRI: serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Values are expressed as n (%).

There are few publications on pregnant women admitted with a high obstetric risk and a psychiatric comorbidity. Our study found that the most common psychiatric comorbidity among pregnant women with a high obstetric risk was major depressive disorder, followed by adjustment disorder and anxiety disorders. These findings generally agree with the literature, which shows that depressive disorder is the most common among pregnant women.4,18,32,33

The finding of major depressive disorder (MDD) in 29% of our pregnant women is similar to the 21% value found by Harvey et al.21 among patients assessed by liaison psychiatry in Australia. At the same time, our value is higher than results found in the US for MDD, including 17.8% in the population study by Kang-Yi et al.,4 8.4% in the epidemiological study by Vesga-Lopez et al.34 and 4.8% found by Melville et al.17 in prenatal obstetric care at a university clinic, or the prevalence of 12.7% estimated to present during pregnancy reported in the review by Yonkers et al.20 These discrepancies can be explained by the particular characteristics of the different studies, which mean they are not comparable with ours. There have been two Colombian studies conducted in high-risk obstetric patients, one in Cali by Guerra et al.35 and the other in Medellín by Bonilla-Sepúlveda,36 that, using scales designed to record depressive symptoms, detected a prevalence of depressive symptoms of 30.2% and 32.8%, respectively, and are thus not comparable with our study either. Based on the observations recorded, the data found in this study coincide with those mentioned above, insofar as depression, regardless of whether its detection is categorical or by symptoms, is prevalent among the psychiatric disorders present in pregnant women3,4,20,23–25 and constitutes an important risk factor that warrants prenatal detection and intervention.

With regards to adjustment disorder, very few studies have been performed in the pregnant population. Our result of 21.8% is not comparable with the figures published in different prenatal studies of pregnant women, not specified as high risk, such as those by Knop et al. (87%),22 Harvey et al. (36.5%),21 Kang-Yi et al. (8.3%)4 and Alvardo-Esquivel et al. (5%),37 nor with the prevalence of 31.6% reported by Gómez et al.38 in pregnant women with a high obstetric risk referred to a prenatal psychology service. The inconsistency with our findings is due to the design type of the different studies and because they were conducted in diverse population groups.

Based on DSM-5 criteria, our prevalence of 12.5% of anxiety disorders in high risk obstetric patients closely resembles the prevalence of 13% reported by Vesga-López et al.,34 but is higher than the 8% prevalence rate reported by Kelly et al.39 in prenatal control patients. Neither of the two studies focused on pregnant women at a high obstetric risk, so we suggest that the result should be reproduced, especially if we take into account that the vast majority of studies on anxiety and pregnancy have been conducted by analysing the symptoms of anxiety and not the disorders themselves; or because operational criteria were not used for the diagnosis or the diagnosis was not arrived at by means of structured interviews, but by using self-assessment scales instead; or because the results are reported together with depression, due to their common comorbidity, or because these two conditions occur concomitantly.8,9,33,40,41

A total of 17.3% of the sample studied had a main psychiatric diagnosis or an active secondary psychiatric diagnosis of substance use disorder, with just over half of the sample using multiple substances (two or more substances). The relationship between pregnancy and substance use is known, and different types of studies show that between 2.4% and 21% of pregnant women use, abuse or are dependent on substances during pregnancy. These situations can have a significant impact on maternal, foetal and neonatal morbidity.4,21,42–44 Our finding is along the same lines.

With regards to obstetric risk factors obtained using the Prenatal Biopsychosocial Risk Assessment scale, the classification as high biopsychosocial risk in the majority of patients is a finding similar to that found in some Latin American and Asian countries where the same scale has been used, and this high risk is associated with adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes.30 The most prevalent medical comorbidities recorded by the scale were hypertension, gestational diabetes, and recurrent spontaneous abortions and pre-eclampsia, which are well documented in the literature and are important perinatal risks.18,21,32,45–47 Meanwhile, the inadequate social-family support component had a prevalence of 27%, accompanied by a high prevalence (more than 88%) of the severe anxiety variable, which encompasses depressive symptoms, emotional distress and/or neurovegetative symptoms. This finding is relevant in terms of risk factors shared in multiple publications, as factors that indicate the need to socially and therapeutically intervene.17–19

With respect to the psychiatric drug treatments received by the pregnant women studied, these are reported and supported by the literature. Publications from the last few decades show that, when required, and after considering the risk/benefit ratio, there is no limitation for the rational use of such drugs in pregnant women with psychiatric illness.20,48,49

Our results should be read whilst bearing some limitations in mind. As this was a descriptive study based on secondary sources, it was not possible to analyse risk factors. Furthermore, it is likely that there were errors in the recording of some information in the patient medical records and the data could not be confirmed beyond what was stated in the source document. Due to the characteristics of the sample studied, the results cannot be extrapolated to other high-risk pregnant population groups.

This is the first study with these characteristics to be conducted in Colombia. It provides valuable sociodemographic and clinical information for future analytical projects in our line of research in perinatal mental health and for making decisions about the overall care of pregnant patients.

ConclusionsThe findings show that pregnant women who are at a high obstetric risk also have a high psychosocial risk and a risk of psychiatric comorbidities. During prenatal assessments, it is important to actively screen for a history and symptoms of mental illness in order to promptly diagnose psychiatric illnesses for the purposes of treatment and subsequent follow-up by psychiatry. The psychiatrist's role in this group of patients is of vital importance and positively impacts the functionality and quality of life of pregnant women and their children, as well as helping to reduce the risk of perinatal complications.

FundingCentro de Investigación para el Desarrollo y la Innovación [Research Centre for Development and Innovation] (CIDI) of Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest in this article.

Article based on the thesis "Psychiatric diagnoses in patients from the high-risk obstetric service of Clínica Universitaria Bolivariana assessed by psychiatry between 2013 and 2017". Faculty of Medicine, Universidad Pontificia Bolivariana, Medellín; 2020.