This study aims to determine differences between the number of underlying medical conditions, depression, and anxiety, when controlling for the covariates of age, sex, and completed education.

MethodsParticipants (n = 484) indicated the number of medical conditions present during the survey, also including the PHQ-9 and GAD-7, to assess depression and anxiety, respectively.

ResultsDifferences were found between groups of medical conditions and the combined values of PHQ-9 and GAD-7 after controlling for the covariates mentioned above (F4,954 = 5.78; Wilks’ Λ = 0.95; P < 0.0005). The univariate tests showed differences for PHQ-9 (F2,478 = 8.70; P < 0.0005) and GAD-7 (F2,478 = 11.16; P < 0.0005) between the 3 groups. Finally, post-hoc analysis showed differences between participants with one medical condition and with no medical condition (PHQ-9: MD = 1.82; 95%CI, 0.25–3.40; GAD-7: MD = 1.73; 95%CI, 0.55–2.91), and between participants with more than one medical condition and participants with no medical condition (PHQ-9: MD = 3.10; 95%CI, 1.11–5.10; GAD-7: MD = 2.46; 95%CI, 0.97–3.95).

ConclusionsOur results suggest that people who had a medical condition during the COVID-19 pandemic were more prone to developing severe symptoms of anxiety and depression.

El objetivo de este estudio es determinar diferencias entre el número de condiciones médicas subyacentes, depresión y ansiedad, al controlar por las covariables edad, sexo y educación completa.

MétodosLos participantes (n = 484) indicaron el número de condiciones médicas presentes durante la encuesta, incluyendo también el PHQ-9 y GAD-7 para evaluar la depresión y la ansiedad respectivamente.

ResultadosSe hallaron diferencias entre los grupos de afecciones médicas y los valores combinados de PHQ-9 y GAD-7 después de controlar por las covariables mencionadas (F4,954 = 5,78; Wilks’ Λ = 0,95; p < 0,0005). Las pruebas univariadas mostraron diferencias para PHQ-9 (F2,478 = 8,70; p < 0,0005) y GAD-7 (F2,478 = 11,16; p < 0,0005) entre los 3 grupos. Finalmente, el análisis post-hoc mostró diferencias entre los participantes con una condición médica y sin ninguna condición médica (PHQ-9: MD = 1,82; IC95%, 0,25−3,40; GAD-7: MD = 1,73; IC95%, 0,55−2,91) y entre participantes con más de 1 afección médica y participantes sin afección médica (PHQ-9: MD = 3,10; IC95%, 1,11−5,10; GAD-7: MD = 2,46; IC95%, 0,97−3,95).

ConclusionesNuestros resultados indican que las personas que tuvieron una afección médica durante la pandemia de COVID-19 son más propensas a desarrollar síntomas graves de ansiedad y depresión.

Depression and anxiety are the most common mental health disorders in the world. They are the primary causes of years lost due to disability (YLD) and involve high long-term costs for healthcare systems.1 Extreme global conditions, such as a pandemic, can lead to a range of abrupt changes in society (for example, lockdown, social restriction and curfew), which can lead to an increase or worsening of these mental health disorders.2–6 Some underlying conditions, such as medical diagnoses or previous health problems, can also exacerbate these mental health disorders in a pandemic and cause serious psychological consequences and greater functional limitations.7 This has been the case with the recent COVID-19 pandemic, with adverse mental health effects8 and a greater emotional impact on people with underlying medical conditions9. The latest epidemiological reports, also distributed among the population, mostly correlate these conditions with the lethal progression of COVID-19,10 which has generated more fear and avoidance behaviours in individuals with previous health problems.11 It would appear that people with previous medical conditions may have different concerns related to the COVID-19 pandemic and its social consequences.12

Studies evaluating anxiety and depression in people with underlying medical conditions, particularly people with anxiety and depression symptoms, are essential, as chronic multimorbidity is generally associated with a poorer quality of life13,14 and impaired mental health.15,16 These last variables are additional risk factors for major depression and anxiety symptoms.17,18 Lastly, assessing both anxiety and depression in patients with underlying medical conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic will contribute to knowledge about the impact of COVID-19 on mental health.

Therefore, the main aim of this study was to identify any relationship between the number of underlying medical conditions and symptoms of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic in a sample of the general population of Lima (Peru), controlling for the variables age, gender and completed education. This last variable was included as a confounding factor, since incomplete education in previous studies has been correlated with more depression and anxiety.19–22 Age and gender have also shown correlations with symptoms of anxiety and depression in previous studies during the COVID-19 pandemic,23,24 so these variables were also included as confounding factors. The hypothesis is that medical conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic would be related to an increase in symptoms of depression and anxiety after correcting for the variables age, gender and completed education.

MethodsThe following information was extracted for analysis from a database belonging to this working group and covers the evaluation, published elsewhere,25,26 of the emotional impact during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some methodological aspects (such as participant selection) from our previous studies were retained and continued in this study.

Study design and participation criteriaFrom July 2020 to February 2021, we initially collected information from 563 participants from the metropolitan area of Lima (Peru) for a cross-sectional observational study. However, 79 participants who provided incomplete information were excluded from the study, leaving 484 participants.

Each participant completed an electronic survey with general socioeconomic, psychometric and medical history information. The medical history also included the presence and number of underlying medical conditions. Participants were included if they agreed to take part by giving their informed consent, were over 18 years of age, and had sufficient knowledge of the Spanish language.

Participants who did not meet the inclusion criteria or had serious medical conditions that could limit their ability to complete the online survey (for example, learning disabilities, illiteracy and blindness) were excluded.

Since the primary endpoint of this study was the relationship between the number of underlying medical conditions in the general population and the occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms, anyone involved in active medical treatment for COVID-19 or who had medical and professional knowledge about COVID-19 was excluded. This excluded medical students and healthcare workers. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia (UPCH). The ethical procedures of the study were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the standards of the American Psychological Association (APA).

Online surveyFirst, information was collected from participants in an online survey. These surveys were programmed with a free online survey program (Google Forms, Google Inc., United States), to avoid in-person evaluation and following the guidelines and recommendations against COVID-19.25,26 The online survey was distributed in different social networks (for example, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn) and used the principles of snowball sampling for data collection.25,26 The online survey included questions concerning socioeconomic status (age, gender and education), medical history (presence of medical conditions, number of medical conditions, medication, type of medications) and psychometric data (anxiety and depression symptoms). The variable number of underlying medical conditions were classified into three categories: no medical condition; one medical condition; and more than one medical condition.

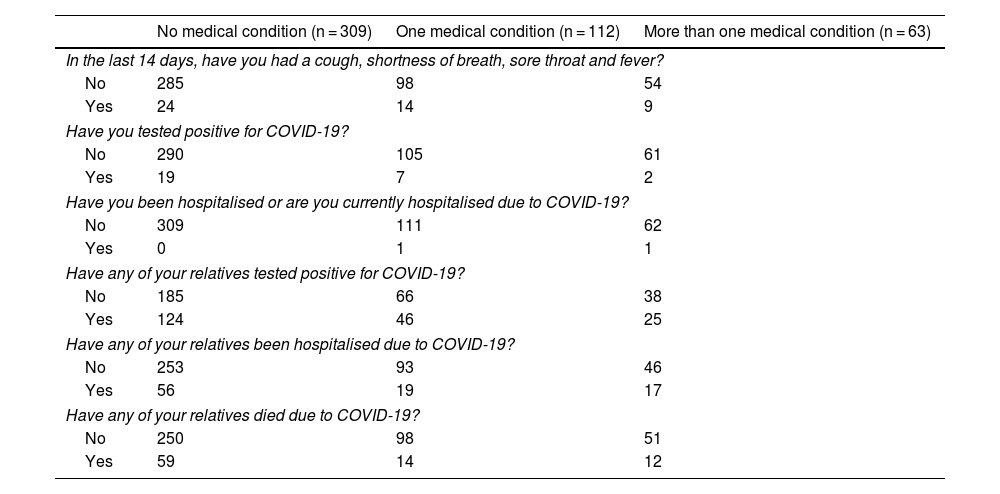

The survey included additional questions about COVID-19 infection or exposure to the virus as descriptive variables. These questions included: previous infection (In the last 14 days, have you had a cough, shortness of breath, sore throat and fever?); positive COVID-19 results (Have you tested positive for COVID-19?); previous hospitalisations for COVID-19 (Have you been hospitalised or are you currently hospitalised for COVID-19?); relatives with positive COVID-19 results (Have any of your relatives tested positive for COVID-19?); relatives hospitalised due to COVID-19 (Have any of your relatives been hospitalised due to COVID-19?); and relatives who died due to COVID-19 (Have any of your relatives died due to COVID-19?).

Anxiety and depression symptomsThe Peruvian version of the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) was used to evaluate the depressive symptoms. This questionnaire has been validated for Peru and its results have been published elsewhere.27 The PHQ-9 score ranges from 0 to 27; the higher value represents greater severity of depressive symptoms. This instrument demonstrated significant internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha = 0.87) and defines different degrees of severity: minimal (1–4 points); mild (5–9 points); moderate (10–14 points); and severe (15–27 points).27

The Peruvian version of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7) was used to evaluate anxiety symptoms. The GAD-7 shows a score between 0 and 21; the higher score represents the greater severity of anxiety symptoms. This instrument is also validated in Peru28 and shows significant internal consistency (α = 0.89). The GAD-7 anxiety scores also define different categories of severity, namely: minimal (0–4 points); mild (5–10 points); moderate (11–15 points); and severe (16–21 points).28

Statistical analysisStatistical analyses were performed with the SPSS program, version 25.0 (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences, International Business Machines Corporation, United States). Graphs were designed with Prism 8 GraphPad (GraphPad Software Inc., United States).

First, all variables used in the analysis were represented in tables and, where possible, described as mean ± standard deviation or counts with ratio values. Data was rounded to the next decimal place to obtain results with two decimal places. Values <0.0005 were described as is, while those greater than one million were defined using scientific notation.

For comparisons of mean depression and anxiety scale scores between groups (number of underlying medical conditions), a multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was performed. This statistical analysis was chosen because the MANCOVA allows: (a) evaluating of multiple dependent variables; and (b) determining of significant differences between these multiple dependent variables in two or more groups, controlling for covariates or confounding factors. In this case, the dependent variables of this model were the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores. The factor variable was the number of medical conditions (no medical condition, one medical condition, and more than one medical condition). Additionally, the variables gender, age, and completed education were included in the model as covariates. F tests were marked as significant if the two-tailed p value was <0.05. Partial η2 values were calculated for the effect sizes. These effects were defined as very small (η2p <0.01), small (0.01 ≤ η2p <0.06), moderate (0.06 ≤ η2p < 0.14) and large (η2p ≥0.14).29,30

Finally, as part of the statistical package for the MANCOVA, a post hoc analysis was calculated if the aforementioned analysis revealed significant results for the factor variable (number of medical conditions) and the dependent variables. This analysis was performed using the Bonferroni correction for post hoc analysis, which involves correcting the p values and the confidence intervals. The data from the post hoc analysis were represented in bar graphs in which significant differences between the three groups were highlighted.

ResultsGeneral characteristicsInformation on psychometric and socioeconomic characteristics was classified into three groups according to the variable number of underlying medical conditions (no medical condition, one medical condition, more than one medical condition) and is shown in Table 1. In addition, the descriptive information on infection or exposure to COVID-19 is shown in Table 2, organised according to the three groups mentioned.

General sociodemographic and psychometric data.

| No medical condition (n = 309) | One medical condition (n = 112) | More than one medical condition (n = 63) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic data | |||

| Age (years) | 35.15 ± 12.21 | 42.78 ± 14.77 | 46.22 ± 16.70 |

| Female/male | 192/117 | 75/37 | 44/19 |

| Education (incomplete/complete) | 67/242 | 25/87 | 14/49 |

| Type of education | |||

| Primary | 0/0 | 1/0 | 0/0 |

| Secondary | 3/19 | 2/3 | 0/2 |

| Secondary | 10/28 | 2/15 | 2/6 |

| University | 54/195 | 20/69 | 12/41 |

| On medications (no/yes) | 229/80 | 20/92 | 9/54 |

| Psychometric data | |||

| GAD-7 Values | 4.68 ± 4.27 | 5.90 ± 4.70 | 6.41 ± 5.24 |

| GAD-7 Severity | |||

| Minimum | 166 | 49 | 24 |

| Mild | 115 | 45 | 26 |

| Moderate | 19 | 12 | 9 |

| Severe | 9 | 6 | 4 |

| PHQ-9 Values | |||

| PHQ-9 Severity | 5.95 ± 6.11 | 6.90 ± 5.94 | 6.74 ± 6.18 |

| Minimum | 156 | 50 | 23 |

| Mild | 90 | 33 | 20 |

| Moderate | 29 | 18 | 10 |

| Severe | 34 | 11 | 10 |

GAD-7: Generalized anxiety disorder 7 items; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire 9 items.

Values are expressed as n or mean ± standard deviation.

General (descriptive) information regarding COVID-19 infection or exposure.

| No medical condition (n = 309) | One medical condition (n = 112) | More than one medical condition (n = 63) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| In the last 14 days, have you had a cough, shortness of breath, sore throat and fever? | |||

| No | 285 | 98 | 54 |

| Yes | 24 | 14 | 9 |

| Have you tested positive for COVID-19? | |||

| No | 290 | 105 | 61 |

| Yes | 19 | 7 | 2 |

| Have you been hospitalised or are you currently hospitalised due to COVID-19? | |||

| No | 309 | 111 | 62 |

| Yes | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Have any of your relatives tested positive for COVID-19? | |||

| No | 185 | 66 | 38 |

| Yes | 124 | 46 | 25 |

| Have any of your relatives been hospitalised due to COVID-19? | |||

| No | 253 | 93 | 46 |

| Yes | 56 | 19 | 17 |

| Have any of your relatives died due to COVID-19? | |||

| No | 250 | 98 | 51 |

| Yes | 59 | 14 | 12 |

COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019.

In terms of the medical conditions, there were a total of 285 diagnoses. Among the participants with underlying medical conditions, 112 (64%) had only one and 63 (36%) had more than one. Of the medical conditions, the most common was hypertension (41 of 285 diagnoses), followed by bronchial asthma (24 of 285 diagnoses), major depression (23 of 285 diagnoses), hypothyroidism (19 of 285 diagnoses), diabetes mellitus (13 of 285 diagnoses) and metabolic syndrome (10 of 285 diagnoses).

Examining the medication being taken by all the participants with medical conditions, a total of 381 medications were prescribed. The most commonly prescribed type was vitamins (34 times), followed by angiotensin II receptor antagonists (29 times), serotonin reuptake inhibitors (28 times), nutritional supplements (26 times), levothyroxine (21 times), benzodiazepines (19 times), oral antidiabetic agents (16 times), non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (15 times), statins (14 times), beta-agonists (11 times) and hypnotics (10 times). Participants without medical conditions also recorded taking medications. In this group, a total of 124 medications were prescribed. The most frequently prescribed were nutritional supplements (30 times), vitamins (24 times), contraceptive pills (15 times) and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (10 times).

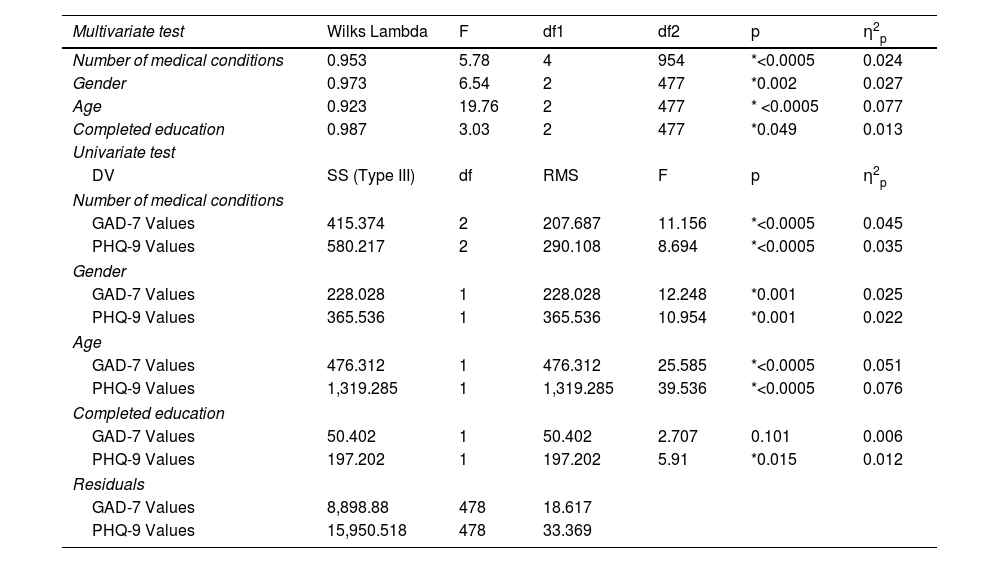

Depression and anxiety symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic: number of underlying medical conditionsDepression (PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7) symptom values measured during the COVID-19 pandemic were analysed using MANCOVA. In this case, the grouping factor was the number of underlying medical conditions. In addition, the variables gender, age and completed education were considered covariates (Table 3). Regarding the multivariate tests of the MANCOVA, the results indicate that there were statistical differences between the underlying medical condition groups in the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 values after controlling for the variables, gender, age and completed education (F4.954 = 5.78; Wilks Lambda = 0.953; p < 0.0005; η2p = 0.024). Furthermore, all selected covariates predicted the values of PHQ-9 and GAD-7 (gender: F2.477 = 6.54; λ = 0.973; p = 0.002; η2p = 0.027; age: F2.477 = 19.76; λ = 0.923; p < 0.0005; η2p = 0.077; completed education: F2.477 = 3.03; λ = 0.987; p = 0.049; η2p = 0.013).

Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA): GAD-7 and PHQ-9 values versus the number of medical conditions (covariates: age, gender and completed education).

| Multivariate test | Wilks Lambda | F | df1 | df2 | p | η2p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of medical conditions | 0.953 | 5.78 | 4 | 954 | *<0.0005 | 0.024 |

| Gender | 0.973 | 6.54 | 2 | 477 | *0.002 | 0.027 |

| Age | 0.923 | 19.76 | 2 | 477 | * <0.0005 | 0.077 |

| Completed education | 0.987 | 3.03 | 2 | 477 | *0.049 | 0.013 |

| Univariate test | ||||||

| DV | SS (Type III) | df | RMS | F | p | η2p |

| Number of medical conditions | ||||||

| GAD-7 Values | 415.374 | 2 | 207.687 | 11.156 | *<0.0005 | 0.045 |

| PHQ-9 Values | 580.217 | 2 | 290.108 | 8.694 | *<0.0005 | 0.035 |

| Gender | ||||||

| GAD-7 Values | 228.028 | 1 | 228.028 | 12.248 | *0.001 | 0.025 |

| PHQ-9 Values | 365.536 | 1 | 365.536 | 10.954 | *0.001 | 0.022 |

| Age | ||||||

| GAD-7 Values | 476.312 | 1 | 476.312 | 25.585 | *<0.0005 | 0.051 |

| PHQ-9 Values | 1,319.285 | 1 | 1,319.285 | 39.536 | *<0.0005 | 0.076 |

| Completed education | ||||||

| GAD-7 Values | 50.402 | 1 | 50.402 | 2.707 | 0.101 | 0.006 |

| PHQ-9 Values | 197.202 | 1 | 197.202 | 5.91 | *0.015 | 0.012 |

| Residuals | ||||||

| GAD-7 Values | 8,898.88 | 478 | 18.617 | |||

| PHQ-9 Values | 15,950.518 | 478 | 33.369 | |||

RMS: root mean square; GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 items; df: degrees of freedom; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire 9 items; SS: sum of squares; DV: dependent variable.

The univariate MANCOVA tests showed differences in PHQ-9 and GAD-7 between the three groups (PHQ-9: F2.478 = 8.70; p < 0.0005; η2p = 0.035; GAD-7: F2.478 = 11,16; p < 0.0005; η2p = 0.045). Furthermore, the covariates gender and age also showed significant differences in PHQ-9 and GAD-7 in the univariate test (gender-PHQ-9: F1.478 = 10.95; p = 0.001; η2p = 0.022; gender-GAD-7: F1.478 = 12.25; p = 0.001; η2p = 0.025; age-PHQ-9: F1.478 = 39.54; p < 0.0005; η2p = 0.076; age-GAD-7: F1.478 = 25.59; p < 0.0005; η2p = 0.051). The covariate completed education only showed significant differences in PHQ-9 in the univariate analysis (PHQ-9: F1.478 = 5.91; p = 0.015; η2p = 0.012).

Further details of the results of the MANCOVA and the multivariate and univariate tests are shown in Table 3.

Post hoc analysis: number of underlying medical conditions (three groups) versus anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemicRegarding the results of the MANCOVA, the univariate analysis showed significant results between the number of underlying medical conditions and the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 values (Table 3). To determine possible differences between subgroups, a Bonferroni post hoc test was calculated for PHQ-9 and GAD-7. For the PHQ-9 scores, this analysis revealed significant differences between participants with one medical condition and those with none (MD = 1.824; p = 0.017; 95%CI, 0.25–3.40), and between participants with more than one medical condition and those with none (MD = 3.104; p = 0.001; 95%CI, 1.11–5.10). For the GAD-7 scores, post hoc analysis also showed significant differences between participants with one medical condition and none (MD = 1.728; p = 0.001; 95%CI, 0.55–2.91), and between participants with more than one medical condition and none (MD = 2.462; p < 0.0005; 95%CI, 0.97–3.95). The remaining post hoc comparisons (between participants with one medical condition and those with more than one) showed no significant differences (Table 4). These findings of group differences in PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores are depicted in Fig. 1.

Pairwise comparisons based on MANCOVA-estimated marginal means of GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores (covariates: age, gender and completed education) with adjustment for multiple comparisons.

| DV | (I) | (J) | MD (I–J) | SE | pb | 95%CI for differencesb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | ||||||

| GAD-7 Values | No medical condition | One medical condition | –1.73 | 0.49 | *0.001 | –2.91 | –0.55 |

| More than one medical condition | –2.46 | 0.62 | *<0.0005 | –3.95 | –0.97 | ||

| One medical condition | No medical condition | 1.73 | 0.49 | *0.001 | 0.55 | 2.91 | |

| More than one medical condition | –0.73 | 0.68 | 0.846 | –2.37 | 0.90 | ||

| More than one medical condition | No medical condition | 2.46 | 0.62 | *<0.0005 | 0.97 | 3.95 | |

| One medical condition | 0.73 | 0.68 | 0.846 | –0.90 | 2.37 | ||

| PHQ-9 Values | No medical condition | One medical condition | –1.82 | 0.66 | *0.017 | –3.40 | –0.25 |

| More than one medical condition | –3.10 | 0.83 | *0.001 | –5.10 | –1.11 | ||

| One medical condition | No medical condition | 1.82 | 0.66 | *0.017 | 0.25 | 3.40 | |

| More than one medical condition | –1.28 | 0.91 | 0.484 | –3.47 | 0.91 | ||

| More than one medical condition | No medical condition | 3.10 | 0.83 | *0.001 | 1.11 | 5.10 | |

| One medical condition | 1.28 | 0.91 | 0.484 | –0.91 | 3.47 | ||

Multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA); estimated marginal means for the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 score means (covariates: age, gender and completed education), with adjustments for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni). GAD-7: Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 items; ns: p ≥ 0.05; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire 9 items.

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

***p < 0.005.

This study investigated the relationship between the number of underlying medical conditions and symptoms of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic, controlling for three covariates (age, gender and completed education). Our findings show that there were significant differences in the GAD-7 and PHQ-9 scores during the COVID-19 pandemic according to the variable number of underlying medical conditions. Furthermore, the univariate test of both psychometric evaluations during this pandemic also revealed significant differences according to the number of underlying medical conditions. Post hoc analyses revealed that participants with no medical conditions had lower PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores than those with medical conditions during the pandemic. However, post hoc comparisons between participants with one medical condition and those with more than one showed no significant differences in GAD-7 and PHQ-9 during the COVID-19 pandemic.

To our knowledge, there are very few studies analysing the relationship between underlying medical conditions, depression and anxiety. Of these, a recent observational study by Al-Rahimi et al. showed that chronic diseases and taking immunosuppressants were related to increased health anxiety, measured with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score (HADS).13 Additionally, the study's authors found that women and older participants with chronic illnesses were more likely to have high levels of anxiety. Our study reported similar results, with depression and anxiety values more significant during the COVID-19 pandemic in participants with underlying medical conditions compared to those with no medical conditions. Since age and gender are correlated with depression and anxiety, they were corrected for using MANCOVA, and significant results were obtained from both psychometric evaluations. Furthermore, they coincide with the findings of Al-Rahimi et al.13 to the extent that our participants with underlying medical conditions also showed high levels of depression and anxiety. These individuals are highly likely to suffer more worry, fear, sadness and hopelessness in situations like the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings similar to our study are reported in Özdin et al.,31 who found significant correlations between previous chronic illness and anxiety symptoms. Additionally, people with previous chronic illnesses had higher depression and anxiety scores. Other findings, such as those of Meaklim et al.32 show that, compared to those without sleep disorders, participants with pre-existing insomnia frequently suffered symptoms of depression and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although our study did not assess sleep disturbances, chronic insomnia could also be considered a medical condition. Its presence before the COVID-19 pandemic was correlated with higher values of depression and anxiety, as well as suicidal ideation.32 The study by Tasnim et al.15 also assessed underlying medical conditions, depression and anxiety, similar to our study. In that study, depression and anxiety scores were higher among participants with chronic medical conditions, such as asthma, hypertension and obesity. It is worth noting that this study has similarities with our findings for two reasons. First, higher PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores in participants with underlying medical conditions; second, the participants in our study with underlying medical conditions had several shared characteristics with those in the study by Tasnim et al. For example, the most common underlying medical conditions were hypertension, asthma, diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome, similar to our study.

Our results showed that participants with underlying medical conditions had higher scores for anxiety and depression than participants with no underlying medical conditions. One possible explanation for these findings is that people with underlying medical conditions constantly receive information from different media (for example, internet, news, magazines) about the negative consequences of COVID-19 and its severity in people with chronic medical conditions. In addition, the problems created by the idea that health resources should be directed preferentially to COVID-19-infected patients, to the detriment of medical care for other medical conditions, has increased anxiety and depressive symptoms in some individuals with chronic medical conditions who need other services.31 The fear of contracting COVID-19 felt by people with underlying medical conditions could also contribute to the rapid onset of mental health problems, such as anxiety and depression, and cause more fear, sadness and social withdrawal.

LimitationsIt is essential to consider the possible limitations of this study. First, both the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 showed a floor effect in this study, which led to skewed distributions. However, this limiting factor slightly affected the MANCOVA (Box's M test = 12.45; p = 0.05; Levene test for GAD-7: F2.481 = 2.33; p = 0.09; Levene test for PHQ-9: F2.481 = 1.33; p = 0.27). Second, the sampling procedure of this study could have altered the randomisation principle and caused selection bias. This study used snowball sampling to distribute the online survey through different social networks. However, people without access to the internet or social networks were excluded from participating, given the low probability of them accessing the survey. However, the COVID-19 restrictions enacted by the government made direct access to participants difficult, so an online survey was appropriate for assessing each potential participant. Furthermore, the online electronic survey was a plausible and reasonable method to collect data, given the circumstances, and avoid any additional risk of COVID-19 infection. Third, information on medical conditions was collected directly from participants and was not reviewed by an intermediate person (such as a doctor), creating a high risk of recall or information bias. Asking participants about their underlying medical conditions or medical history in this way was, however, an acceptable method of collecting this information, as restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic did not allow any other method, like direct assessments, for example. Fourth, the higher proportion of female participants could affect the results obtained. However, previous studies (such as a study by this working group25,26) have shown that women are psychologically affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in larger proportions. The sample size could also have been larger to generalise the desired information beyond the context of the study. However, the potency obtained in this study with 484 participants was 1–β = 0.99, a value higher than the established threshold (1–β = 0.80).

In conclusion, our findings indicate that an underlying medical condition was associated with high levels of anxiety and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic after controlling for potential confounding factors such as age, gender and completed education. Future health policies should consider this relationship, prioritise the treatment of these vulnerable groups, and establish intervention procedures that particularly focus on the reduction of these symptoms. This is especially important given the considerably diminished quality of life people with underlying medical conditions are likely to have as a result of the psychological consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic.

FundingThis study was not funded by any industry, society, company or educational institution. Furthermore, no external institutions influenced the design of this study.

Conflicts of interestNone.