Medical education has been changing, and the evaluation strategies that make it possible to address not only theoretical knowledge but also clinical skills. In Mental Health, these skills play a central role. The Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE) is one of the evaluations that could assess clinical skills. This article describes the implementation and performance for the evaluation of undergraduate students since the OSCE’s introduction in 2015.

MethodsAn explanation of the implementation is made, and a description of the OSCEs carried out to undergraduate medical students in the second semester of mental health, using the databases of the final practical examinations during those years. The perception of mental health teachers is also described.

ResultsThe mental health OSCE implemented in 2015-2, is developed in the Simulated Hospital of the University and has five stations (interview, mental examination, diagnosis, treatment and information to the family and ethics). Between 2016-2 and 2019-2, 486 students performed OSCE with an average score of 3.85 (scale 0–5). It was observed that the grade obtained when evaluating anxiety disorders was below average, that of affective disorders above average, while that of psychotic disorders was within the average. The professors highlight the versatility, the comprehensive objective evaluation of the practical and theoretical aspects, and the possibility of comparison between the different groups.

ConclusionsThe OSCE is an examination that provides the possibility to evaluate the competences in psychiatry of medical students and allows the identification of the aspects to be improved in the teaching learning process.

La formación médica ha venido transformándose, así como las estrategias de evaluación, lo que permite abordar, además de los conocimientos, las habilidades clínicas. En salud mental estas habilidades desempeñan un rol central. El Examen Clínico Objetivo Estructurado (ECOE) es una de las evaluaciones que tiene este potencial. El objetivo del presente artículo es describir la implementación y el desempeño que han tenido los estudiantes de pregrado desde la introducción de este en el año 2015.

MétodosSe recuenta la implementación y se describen los ECOE realizados a estudiantes de pregrado de Medicina que cursan el segundo semestre de Salud Mental tomando las bases de datos de los exámenes prácticos finales. Además se describe la percepción de los docentes del área.

ResultadosEl ECOE de salud mental se implementó en 2015-2, se desarrolla en el Hospital Simulado de la Universidad y cuenta con 5 estaciones (entrevista, examen mental, diagnóstico, tratamiento e información a la familia y ética). Entre 2016-2 y 2019-2, 486 estudiantes pasaron el ECOE con una nota promedio de 3,85 (baremo de 0 a 5). Se observó que la nota obtenida al evaluarse trastornos de ansiedad estuvo por debajo del promedio; la de trastornos afectivos, por encima del promedio y la de trastornos psicóticos, dentro del promedio. Los docentes resaltan la versatilidad, la mirada objetiva integral de los aspectos prácticos y teóricos y la posibilidad de comparación entre los diferentes grupos.

ConclusionesEl ECOE brinda la posibilidad de evaluar las competencias en acción de los estudiantes de Medicina y permite la identificación de qué aspectos mejorar en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje.

Assessment is an integral part of the teaching-learning process and is one of the pillars of curricular coherence.1 In general, it is divided according to its purposes into formative and summative. Formative is focused on optimising or strengthening learning, reflection and promoting training in personal values or competencies. Meanwhile, summative seeks to establish the expected level of achievement of a learning outcome, given by particular knowledge or the corresponding mark, in order to take on a higher level of responsibility in accordance with the defined supervision.2

Taking this into account, medical education has undergone a transformation in recent years, as it has been necessary to include assessments which are able to make a structured measurement of the performance of the medical student, specifically regarding the acquisition of clinical skills.3 In this context, in the 1970s, the neurologist Harden introduced the Objective Structured Clinical Examination (OSCE). The OSCE involves a circuit consisting of a series of stations where the student has an encounter lasting 10−15 min with a simulated patient. This allows the standardised and structured assessment of clinical skills in a simulated environment, which provides a quick, direct observation of multiple skills. The chief utility of the OSCE is the measurement of skills such as obtaining a medical history, performing a physical examination, creating a treatment plan, providing information, empathy, communication, the doctor-patient relationship and the ability to respond to unexpected situations.4,5

This transformation has also permeated the teaching-learning process in specific areas such as Mental Health and Psychiatry.6 However, there is less literature on OSCE for these areas. In this field, Famuyiwa et al.7 wrote the first report in 1991 on undergraduate assessment. They found that it offers numerous advantages, such as sensitivity to understanding the clinical knowledge of students from different areas and levels, assessment of professional skills, problem-solving, development of communication skills and empathy with patients, in addition to focusing attention on the objectives of students and teachers.

In addition, mental health OSCE demonstrate certain versatility, since they can be applied to different groups of students, such as undergraduates, postgraduates or nursing students, presenting them according to the scientific needs and scope of practice of each specific group. In the case of undergraduate Medicine, a pyramid model8–10 is described in which students must support not only their knowledge but also how they apply it in clinical practice. To this end, communication skills, taking a medical history, doctor-patient relationship, interview, treatment plan, delivery of information and empathy are prioritised. However, the heterogeneity of the headings used to assess undergraduate students in different institutions around the world remains a challenge, specifically taking into account the need to lengthen the time used at each station due to the characteristics of the interview and assessment in mental health.8,10,11

In view of this situation in Colombia, and particularly in the Faculty of Medicine of the Universidad de La Sabana, a study programme transformation process was started in 2003, defining outcome-based syllabus measured by skill assessment, defining signs and symptoms, family medicine, research and the humanities as core syllabus areas.12 With this transition, syllabus adjustments were transforming the way of teaching the components of mental health and psychiatry (previously divided into three subjects: Developmental Psychology, Medical Psychology and Psychopathology), regrouping them into two integrated subjects (Mental Health I and Mental Health II) and modifying the strategies and methods for teaching master classes exclusively for other types of strategies more focused on the student.2,3,6

In view of these adjustments, it became necessary for a change in the assessment and for traditional theoretical knowledge, assessed with multiple choice or open response exams, to be complemented with the formative and summative assessment of knowledge, doing and being skills. This led to the OSCE being adopted for the first time as a form of Mental Health assessment in the faculty in 2015-2, in accordance with the humanistic training in the profile defined by the programme.13

These considerations, added to the demonstration of its validity and reliability in assessing skills,14 have made OSCE a benchmark for clinical assessment. However, given the limited literature available regarding experiences in our setting with this type of assessment to help with the development of quality instruments such as scales or checklists,10,15,16 this article describes the implementation and structure used for this exam in the Universidad de La Sabana's Department of Mental Health, also reporting the performance of the students and the assessments of the lecturers, for the purposes of contributing to the implementation, structuring and validation of objective exams in the region.

MethodsWe describe the OSCE for students in the seventh semester of medicine, at which time they have the mental health clinical rotation, and how it is currently carried out based on the documentary records of the exams since their inception.

In addition, data was collected on the subjects assessed and the marks of all medical students enrolled in the Mental Health II course (practical mental health subject) in the periods 2016-2 to 2019-2 (7 semesters) who were assessed at the end of the mental health rotation using the OSCE. This data was obtained from the original electronic templates used for marking, although the record for two groups (approximately 40 students) was lost. Data from the first year (2015-2 and 2016-1) was not included due to a technical problem that deleted all existing information (virus).

The lecturers' perceptions were obtained through a three-item questionnaire sent by post to the five lecturers in the department who carried out the OSCE.

Once the data was extracted and recorded, a database was created and, using dynamic tables, a descriptive statistical analysis was performed. Absolute and relative frequencies were calculated for the categorical variables, and measures of central tendency and standard deviation were calculated for the continuous variables. Finally, the considerations of the lecturers involved in the implementation of this exam were analysed, taking into account three points: advantages, disadvantages and aspects to improve.

ResultsImplementation of the OSCE in the Department of Mental HealthFor the implementation of the OSCE in mental health, training was carried out with the National Board of Medical Education (NBME), and the previous experience of the faculty in the implementation of this type of exam in Internal Medicine was taken into account.

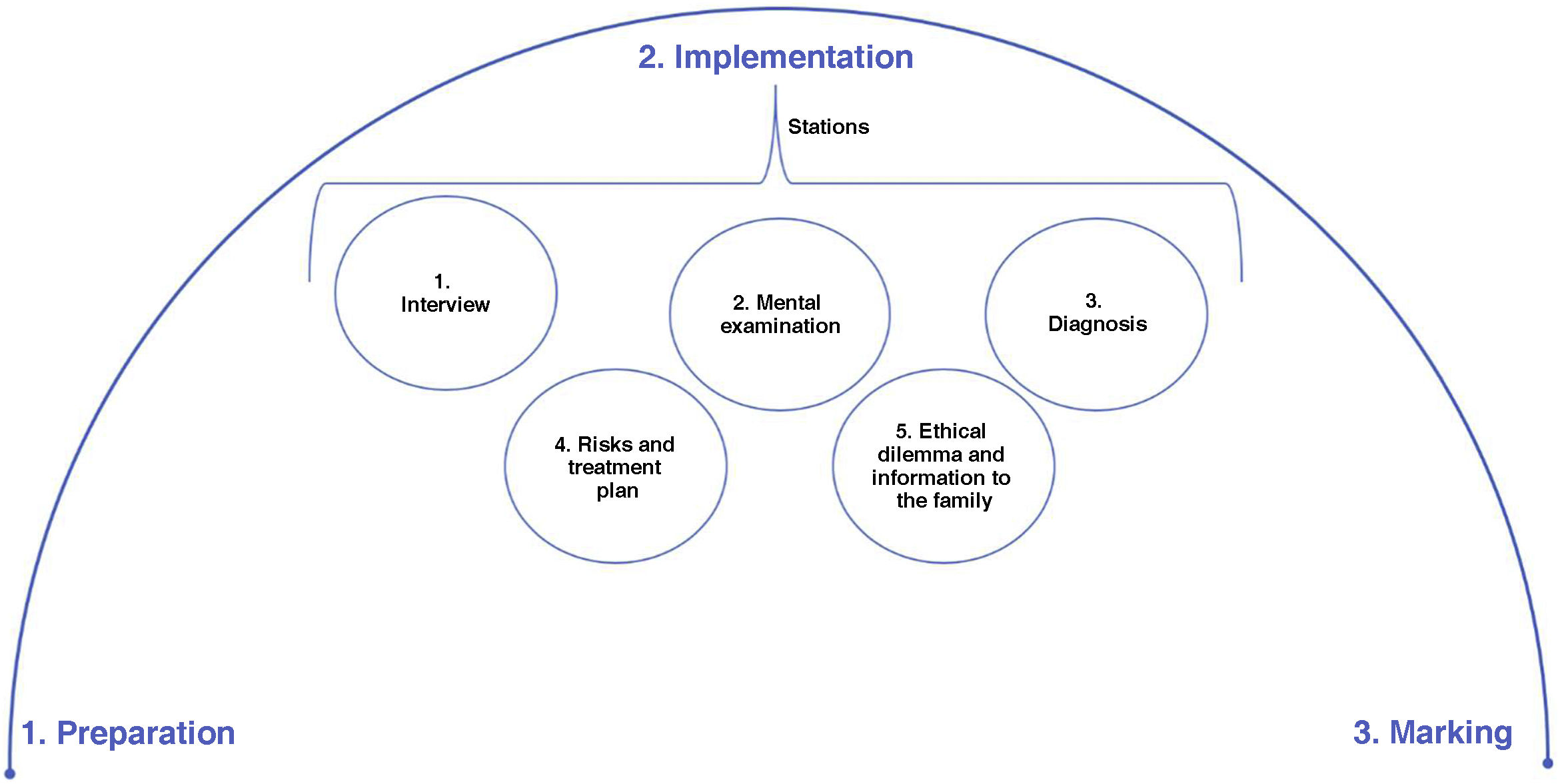

The process used to structure each assessment consists of three phases that go beyond simply its completion, including an initial preliminary or preparation phase plus a practical or completion phase, culminating with the marking of the exams (Fig. 1).

Originally, the first implementations of the OSCE in the Department (2015-2 to 2016-2) were carried out under a structure with four stations: interview; mental examination; diagnoses and risks; and management plan. Psychiatry lecturers participated as simulated patients in two subject areas with different clinical cases. Subsequently, from the 2017-1 academic period onwards, a five-station examination, each lasting seven minutes, was set up on the last day of the rotation in the Simulated Hospital. Two subject areas are prepared, each with a simulated patient and a different clinical case. Each phase of the OSCE implementation process used in the department is detailed below.

PreparationIn the Department of Mental Health, it has been defined as a cross-curricular element, which assesses the full process of care for a patient with mental symptoms in all students, with emphasis on and points for observation in interview, signs and symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, ethical aspects and communication with the family, and is why each OSCE station corresponds to one of these areas of emphasis. The first part of the process is to determine what you want to be assessed in relation to the subject content, that is, what aspect of the Mental Health Expected Learning Outcomes is to be assessed and through which disorder. This allows you to choose one from the bank of cases or design a new case.

Each of the cases, in turn, has a process in which peer validation, in this case the department lecturers, helps provide the necessary clarity of the instructions, time, objective and alignment between what is asked of the student and what they should know and know how to do. An assessment heading is prepared for each case and each station, which is also reviewed by everyone.

The actors receive the cases and the scripts with the respective headings one to two weeks beforehand, in order to allow training to ensure the correct demonstration and parameterising of the symptoms. The personification and staging of the context (emergency, hospitalisation, outpatient clinic) are also a fundamental part of the process. Initially the exam was carried out in the Simulation Laboratory, but now it is in the university's Simulated Hospital. In this step, the work of the simulation assistants and the coordination between the Simulated Hospital and the department are essential. This is obtained using specific formats that describe the context of the examination and the particularities necessary in personifying the simulated patients (for example, clothing, appearance) and staging of the context (emergency, with or without a companion, etc).

Finally, the assessment templates are prepared, based on the headings the lecturers will use and the forms for the resolving of the case by the student. Currently the templates and forms are electronic.

ImplementationBefore starting the exam, the stations, the rotation method and what is expected at each of them are explained to the students again. As mentioned above, since 2017-2, there have been five stations, the first with a simulated patient, and at the others they develop the case based on station 1.

Station 1: interview. At this station, they have to conduct an interview with a simulated patient which allows them to reach a diagnosis and a differential diagnosis and assess risks. This assesses the doctor-patient relationship (greeting, introducing yourself as their doctor, establishing eye contact, etc), exploring the reason for consultation, current illness, review of systems, history and questions aimed at differential diagnosis.

Station 2: mental exam. This station is written and they have to complete all aspects of the patient's mental examination based on the interview.

Station 3: diagnoses. At this station they must perform the syndrome-based and specific diagnosis and propose three differential diagnoses.

Station 4: risk identification and treatment plan. Identification of the patient's risks is a core aspect in mental health. Therefore these risks must be recorded at this station and a treatment plan generated in accordance with the main diagnosis and the risks found.

Station 5: ethical dilemma and information to the family. This was the last station to be implemented and closes the cycle of patient care. It assesses how the student gives information to the family and how he or she responds to an everyday bioethical dilemma (for example, voluntary departure of a patient at risk of suicide).

Once all the students pass through the five stations, a debriefing is given in which participants, students and assessing lecturers make a general presentation of the favourable elements and those for improvement at the interview station and the expected answers stipulated in the headings of the remaining four stations.

MarkingPart of the marking begins during the exam time, at station 1 with a simulating actor. The other four stations are marked later using an electronic form and a dynamic template that allows the corresponding calculations to be made. Each station has an estimated weight in the final score and each aspect of the heading, a percentage at each station, which in principle depends on the number of stations used. Finally, the result is given to the student, who can review the exam at any time.

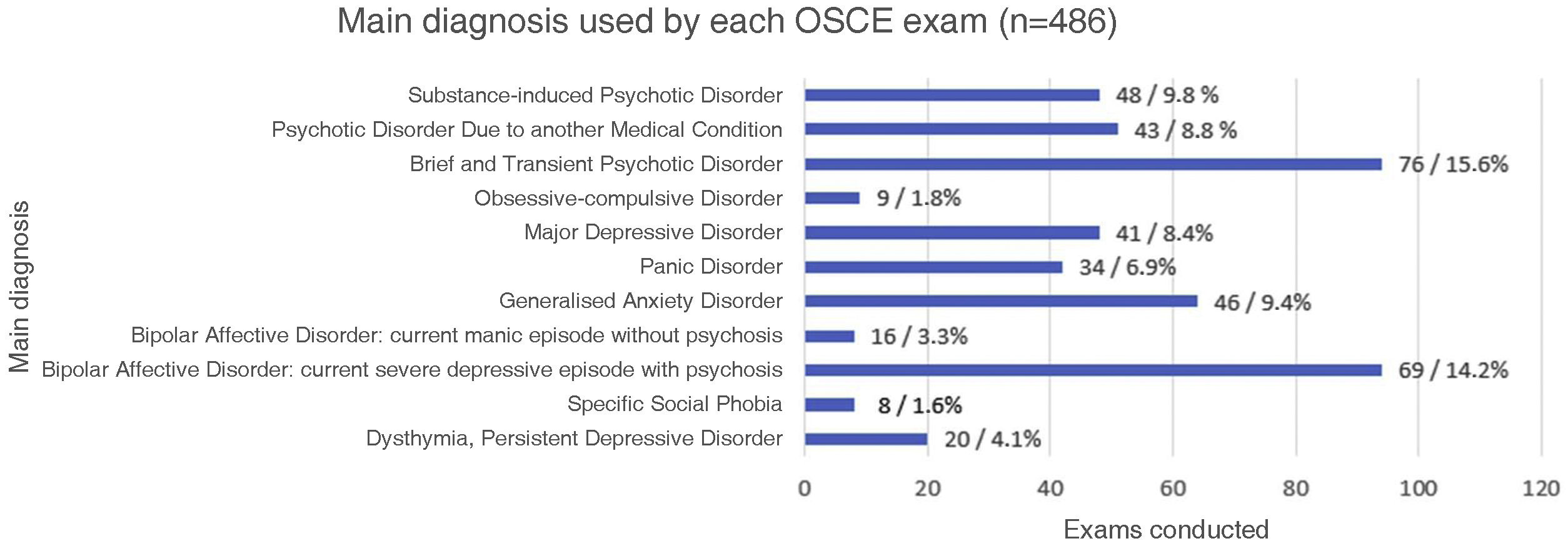

Student performance based on marksGeneral aspectsBetween the 2016-2 and 2019-2 academic periods, 486 students took the OSCE as part of the practical assessment of the Mental Health II subject, with an average mark of 3.85. During this time, 35% of the exams had affective disorders as a general topic (n = 170), while 25.3% were about anxiety disorders (n = 123) and 39.7%, about psychotic disorders (n = 193). Comparing the performance of the students with regard to these subjects, we found that the mark obtained when assessing anxiety disorders was below average (3.72), while that of psychotic disorders was similar (3.88) and that of affective disorders was higher (3.92).

When reviewing each examination according to the main diagnosis assessed on each occasion, we found that 11 different diagnoses were used: dysthymia, specific social phobia (SSP), bipolar affective disorder (BAD) with depressive or psychotic episode, generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), major depressive disorder (MDD), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), brief and transient psychotic disorder (BTPD), psychotic disorder due to another medical condition and substance-induced psychotic disorder. The distribution can be seen in Fig. 2.

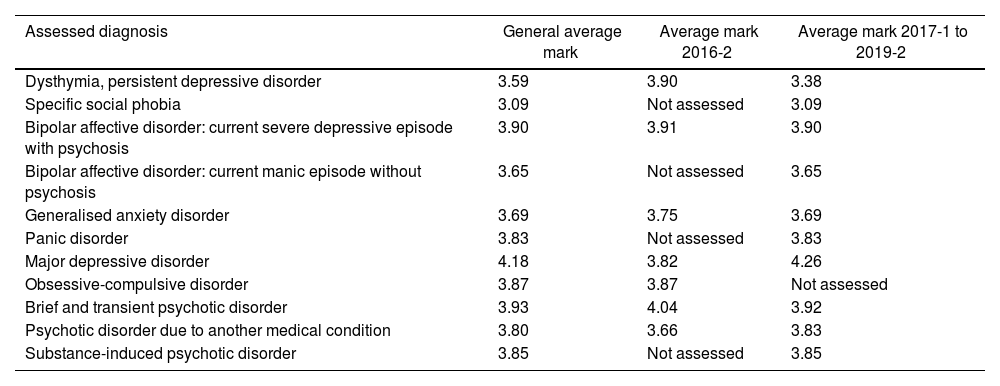

This allows the average mark obtained for each diagnosis to be contrasted. However, in addition to assessing the overall average mark obtained, the grades are divided into two periods due to the configuration of the percentage that corresponds to each station of the exam, as well as the implementation of a fifth station starting from the 2017-1 period. For this reason, undergraduates who took the exam in the 2016-2 period and those who took it between 2017-1 and 2019-2 were analysed separately (Table 1).

Notes according to diagnosis assessed by period.

| Assessed diagnosis | General average mark | Average mark 2016-2 | Average mark 2017-1 to 2019-2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dysthymia, persistent depressive disorder | 3.59 | 3.90 | 3.38 |

| Specific social phobia | 3.09 | Not assessed | 3.09 |

| Bipolar affective disorder: current severe depressive episode with psychosis | 3.90 | 3.91 | 3.90 |

| Bipolar affective disorder: current manic episode without psychosis | 3.65 | Not assessed | 3.65 |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 3.69 | 3.75 | 3.69 |

| Panic disorder | 3.83 | Not assessed | 3.83 |

| Major depressive disorder | 4.18 | 3.82 | 4.26 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 3.87 | 3.87 | Not assessed |

| Brief and transient psychotic disorder | 3.93 | 4.04 | 3.92 |

| Psychotic disorder due to another medical condition | 3.80 | 3.66 | 3.83 |

| Substance-induced psychotic disorder | 3.85 | Not assessed | 3.85 |

Prepared by the authors.

For the 66 students who took the exam in 2016-2, there were four stations, interview, mental examination, diagnosis and treatment plan, which represent 20%, 20%, 30% and 30% respectively of the final mark. For this period, the average mark obtained was 3.86.

When breaking down the exams according to their general topic, the marks obtained in exams that assessed affective disorders were in line with the general average (3.88); the same occurred with psychotic disorders (3.85) and anxiety disorders (3.82), slightly below the average. However, when separated by main diagnosis, we found that the students' performance when assessing GAD and BTPD were below the average both overall and for the period. Meanwhile, the marks obtained when assessing dysthymia, BAD with depressive episodes and BTPD as the main diagnosis were above the general average.

Periods between 2017-1 and 2019-2During this period, for the 420 assessments carried out, the format used was changed. In the first instance, due to the inclusion of a fifth station that complemented the four previously used. This led to the redistribution of the representative percentages of each station in the final mark, which was adjusted to: 15% (interview); 25% (mental examination); 25% (diagnoses); 25% (risks and treatment plan); and 10% (ethical dilemma and information to the family). Students' average mark for this period was 3.85.

In this case, when reviewing the performance for each of the general topics, we found that the lowest average mark corresponded to the assessment of subjects related to anxiety disorders (3.7), which contrasts with the above average performance when assessing affective disorders (3.95), while assessment of psychotic disorders was in line with the average (3.88). Reviewing each main diagnosis, we also found a below average performance when assessing diagnoses such as dysthymia, SSP, GAD and BAD with manic episodes, while the best mark obtained was found when assessing the diagnosis of MDD.

Perceptions of the lecturersIn general terms, the department's teachers agree that one of the main advantages of the implementation of the OSCE lies in its versatility when assessing students, emphasising that it allows a comprehensive objective assessment of the expected practical and theoretical aspects of the students. It allows the clinical skills acquired during the rotation to be assessed, and offers the opportunity to compare these parameters between the different groups and give specific feedback. Enquiring further about this, some lecturers commented: “Different aspects of a psychiatric medical condition are assessed, which tells us whether or not the student has the capacity for observation, assessment, diagnosis and management”; “The practical and theoretical components are assessed equally, involving various aspects of both doing and knowing how to”.

Furthermore, the results of each OSCE make it possible to assess the training given to students, in that we can reflect on the points achieved and the specific ones to improve: what to emphasise; the aspects that generate confusion or difficulty; and, indirectly, how good the modelling and supervision has been.

We also have to recognise the disadvantages. This type of exam limits the assessment of specific subject areas/disorders in mental health as, given the time required for each case, only one disorder per student was assessed, meaning there is also a degree of luck. The lecturers' views were: “Although it is difficult in terms of time, it would be good to assess at least two subjects to ensure it wasn't just a matter of chance for the student, that it happens to be one thing the student doesn't know or exactly the thing they know most about”; “Small areas of specific knowledge are measured. That is, if a student handles 10 topics very well, but one not so well, and that one appears in the OSCE, they may be affected. Or if someone only masters one subject area and it appears in the OSCE, it may not be so objective for their level of knowledge”.

Lastly, another aspect highlighted, despite their training, are the possible differences in representation and interpretation of the participants involved, particularly when having to represent conditions with more discrete symptoms, such as a pattern of constant worry.

DiscussionDoing exams such as the OSCE in mental health has allowed students to be assessed in various dimensions of training in a protected environment. These dimensions and components of a skill are exemplified in “being”, closely related to professionalism, with specific elements such as empathy, communication and bioethical challenges. Then there is “knowing”, in aspects of signs and symptoms, diagnostic approach and treatment in a particular entity, and “know-how”, in complex skills, such as conducting the interview, managing agitation or explaining the health condition to the family.4,5

Depending on the amount of experience accumulated over these years, as widely recommended in the guidelines for the implementation of OSCE, a preliminary study is required to ensure adequate preparation, practice and marking.17–19

When reviewing the assessments carried out on the students, the marks obtained indicate that, in most of the conditions assessed, performance corresponds to the general average for all the exams. However, below-average performance is striking in entities which, in general terms, have a more subtle clinical presentation. Therefore, it is necessary to delve into the reasons why the group of conditions that come under anxiety disorders are those in which students perform poorest.

Conversely, better performance in cases of major depression could be related to familiarity with the symptoms, given their prevalence and greater visibility in recent years, and to the specific emphasis placed in the department on this condition. Unfortunately, we did not find any literature specifying whether these findings are also common in other student populations.

The perception of psychiatry lecturers is similar to other studies in terms of good performance in the know-how for assessing skills in interviews and when facing specific challenges involving communication and clinical encounters with patients with mental symptoms.11,14,20–22

Despite the benefits of the OSCE, it is essential to recognise that the instrument has its limitations and a delimited space, and there are other means of assessment which have better performance, for example, in theoretical knowledge.1,2,6,10

Specifically in mental health, compared to other medical specialisations, the representation of emotional effects and mental and cognitive disorders is a challenge for both participants and students, since these aspects are difficult to teach and assess. Simulated patients may not be sufficiently realistic for the assessment objective, as in the representation of affect and the response to open questions there can be variability in their performance, and it is difficult to represent a clinical condition that they have not personally suffered.9,10,20,23 It is necessary to choose participants well and be attentive to their mental health, as they may have emotional issues in relation to the roles they are playing.16,23

Up to now, each exam has focused only on one disorder, which allows an expression of knowledge, skills and attitudes on a specific topic, but not on several mental illnesses. So the next challenge is an OSCE that includes various diagnoses and cases (blueprints) and allows a broader vision of the students' real knowledge and skills.

Last of all, since the implementation of OSCE, we are looking to strengthen other future academic aspects. Firstly, from the perspective of inter-professionalism and being transdisciplinary, we seek to promote the inclusion of students from other professions in mental health to assess and reinforce aspects such as teamwork. Also, the possibility of including students who have already taken this exam in the planning, practice and marking process for their peers who have not yet had the experience has been suggested, in order to build their skills and promote responsibility in the training of their colleagues.

ConclusionsAssessment is a fundamental part of the teaching-learning process. In medicine, good treatment is based on a good diagnosis, and this is derived from a good interview, physical and mental examination, and the use of appropriate diagnostic aids. This is why the spell undergraduate students spend studying psychiatry is so important, as it involves the great responsibility of ensuring they learn the minimum and learn it well, while understanding the importance of respect for the dignity of patients suffering from a mental illness. This is also why the implementation of increasingly objective training and assessment mechanisms is necessary. The OSCE contributes to this line of thinking, as it allows a more complete and standardised assessment of the student's skills. It requires multiple factors and elements to be considered, as well as a continuous review of the process. This results in better training of future doctors, where they can feel calm and confident assessing and treating patients with psychiatric symptoms as part of a primary mental illness or as a consequence of a general medical condition. All of this means the need for a good analysis process to reach a differential diagnosis.

FundingThis article has not received any funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Presented as Unsupervised Work at the 57th Colombian Congress of Psychiatry, on 2 November 2018 in Cartagena, Colombia.