A sense of entitlement, thoughts of deserving more than others, and belief of having superior abilities compared to other people characterizes narcissistic personality disorder (NPD). Encompassing this personality disorder and other mental conditions, the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) is an evidence-based, dimensional model covering not only clinical symptoms but also pathological traits.

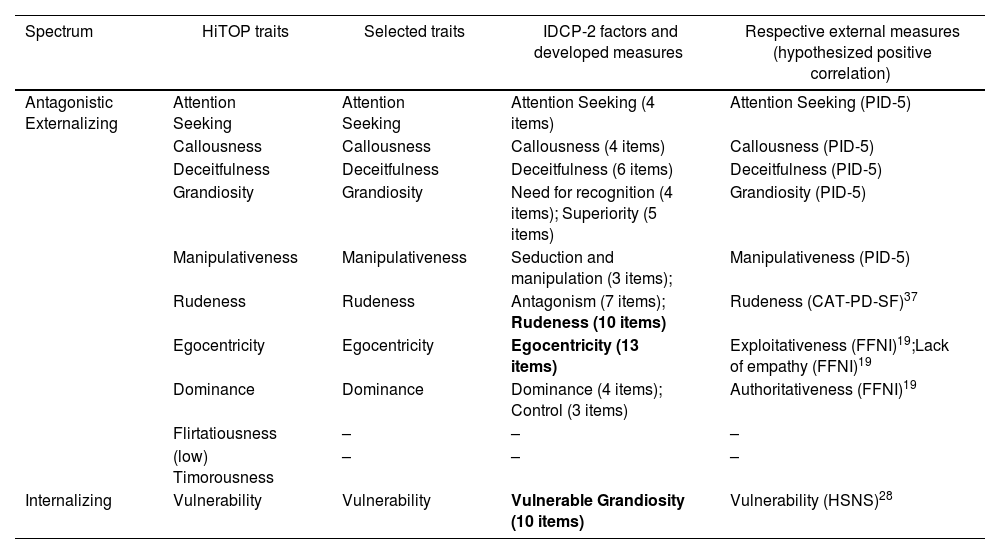

Material and methodsOur study aimed to develop a self-report scale, the IDCP-NPD, for screening pathological traits of NPD from the perspective of the HiTOP facets of the Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5), factors of the Computerized Adaptive Assessment of Personality Disorder-Static Form (CAT-PD-SF), scales of the Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory (FFNI), and the Hypersensitive Narcissism Scale (HSNS).

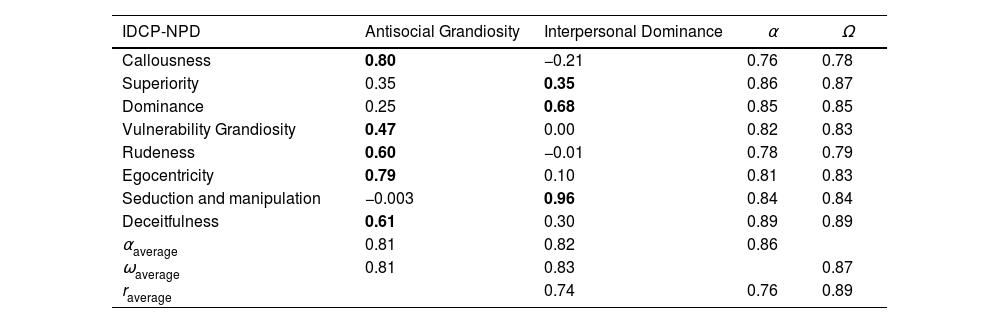

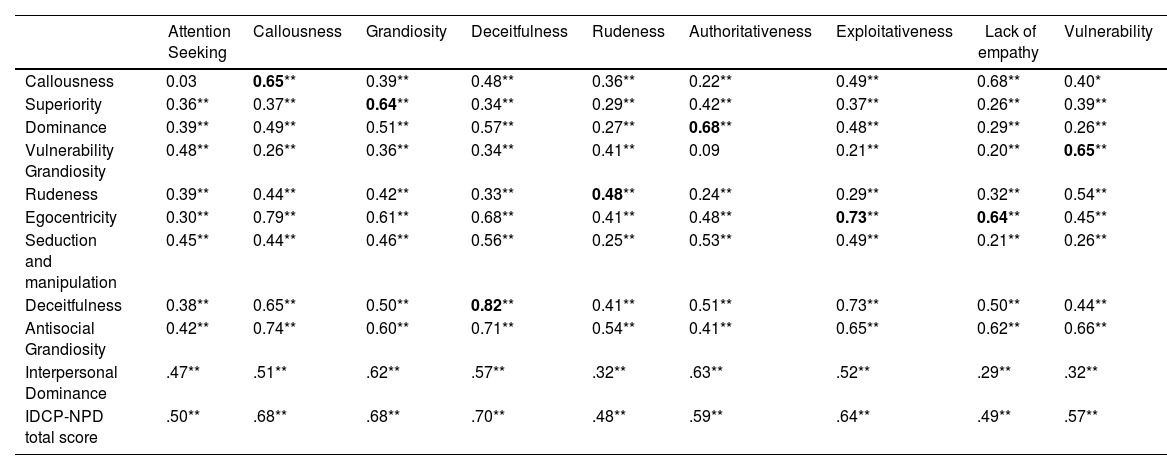

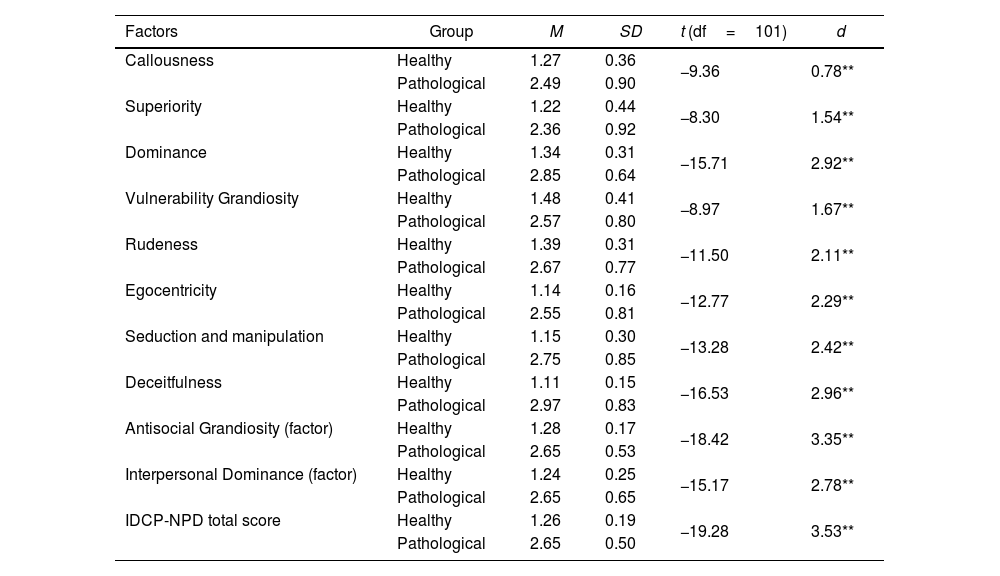

ResultsThe IDCP-NPD comprised 65 items in two factors: Antisocial Grandiosity and Interpersonal Dominance. Internal structure reliability was good (>.80). The factors showed associations with the expected external measures, and the groups based on the scores in the NPD external measures showed big to huge differences.

ConclusionsOur findings suggested the IDCP-NPD is a helpful measure to screen the NPD traits in the clinical context. Additionally, the structure observed for the IDCP-STPD confirms the spectrum level of the HiTOP.

Un sentimiento de derecho, pensamientos de merecer más que los demás y la creencia de tener habilidades superiores en comparación con otras personas caracterizan el trastorno narcisista de la personalidad (NPD). La taxonomía jerárquica de la psicopatología (HiTOP), que abarca este trastorno de la personalidad y otras afecciones mentales, es un modelo dimensional basado en la evidencia que cubre los rasgos patológicos en su rango inferior.

Material y métodosNuestro estudio tuvo como objetivo desarrollar una escala de autoinforme, el IDCP-NPD, para detectar rasgos patológicos de NPD desde la perspectiva del HiTOP, de facetas del Inventario de Personalidad para el DSM-5 (PID-5), de factores de la Evaluación Adaptativa Computarizada del Trastorno de Personalidad Forma Estática (CAT-PD-SF), de escalas del Inventario de Narcisismo de Cinco Factores (FFNI) y de la Escala de Narcisismo Hipersensible (HSNS).

ResultadosEl IDCP-NPD estuvo compuesto por 65 ítems distribuidos en dos factores: grandiosidad antisocial y dominancia interpersonal. La confiabilidad de la estructura interna fue buena (>0.80). Los factores mostraron asociaciones con las medidas externas esperadas, y los grupos basados en las puntuaciones de las medidas externas del NPD mostraron diferencias entre grandes y enormes.

ConclusionesNuestros hallazgos sugirieron que el IDCP-NPD es una medida útil en el contexto clínico para detectar los rasgos de NPD. Además, la estructura observada para el IDCP-STPD confirma el nivel espectral del HiTOP.

Artículo

Comprando el artículo el PDF del mismo podrá ser descargado

Precio 19,34 €

Comprar ahora