The Patient Health Questionnaire is an instrument to assess people's depression. Despite its wide international use, studies are unknown on its psychometric properties in the Colombian population with chronic diseases.

ObjectiveTo estimate the content, construct, convergent, and internal consistency validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire.

MethodologyA sample of 575 individuals selected by opportunity was taken. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 was administered by means of a structured survey through the Internet. Content validity was assessed through relevance, clarity, accuracy, and comprehension by judges; then, a confirmatory factor analysis was applied to estimate construct validity. Confirmatory factor analysis was applied to estimate construct validity. Convergent validity was estimated with the emotional thermometer, GAD-7 and ASA-R. Finally, internal consistency was estimated through the Omega Coefficient.

ResultsAssessment of the relevance, clarity, precision, and comprehension of the items had results ranging on average between 0.89 and 1. The confirmatory factor analysis showed a two-factor structure with a good fit according to different incremental, absolute, and parsimony fit indices. Internal consistency showed a satisfactory result for the total scale (0.83).

ConclusionsThe new version of the questionnaire has adequate metric properties and is recommended for use in the Colombian population with chronic diseases.

El Cuestionario sobre la Salud del Paciente es un instrumento para valorar la depresión. A pesar de su amplio uso internacional, se desconocen estudios sobre sus propiedades psicométricas en la población colombiana con enfermedades crónicas.

ObjetivoEstimar la validez de contenido, constructo, convergente, y la consistencia interna del Cuestionario sobre la salud del Paciente.

MetodologíaSe tomó una muestra de 575 seleccionados por oportunidad. Se aplicó el Cuestionario sobre la Salud del Paciente-9 por medio de una encuesta estructurada a través de Internet. Se evaluó la validez de contenido a través de la relevancia, claridad, precisión y comprensión por jueces, y posteriormente se aplicó un análisis factorial confirmatorio para estimar la validez de constructo. Finalmente, la consistencia interna fue estimada a través del Coeficiente Omega.

ResultadosLa valoración de la relevancia, claridad, precisión y comprensión de los ítems tuvo resultados cuyo promedio osciló entre 0,89 y 1. El análisis factorial confirmatorio evidenció una estructura de dos factores con un buen ajuste según diferentes índices de ajuste incremental, absoluto y de parsimonia. Por su parte, la consistencia interna mostró un resultado satisfactorio para la escala total (0,83).

ConclusionesLa nueva versión del cuestionario posee propiedades métricas adecuadas y se recomienda su uso en la población colombiana con enfermedades crónicas.

Depression, is one of the most significant and pressing health problems globally. Its impact extends beyond the individual setting, affecting families, communities, and societies as a whole.1,2 Within the context of chronic non-communicable diseases (CNCD), depression gains greater relevance due to its close interaction with these prolonged and high-cost health conditions.3,4 The CNCD, also known as chronic non-contagious diseases, are health conditions that persist over time and which, often, are of progressive nature.5 Among them, there are metabolic diseases, such as diabetes, cardiovascular like arterial hypertension, chronic respiratory diseases and other conditions that call for continuous management and constant medical care.6 These diseases have shown to be among the principal causes of morbidity and mortality in Colombia and in other parts of the world.7

The burden entailed by the CNCD is not only limited to physical aspects, rather, it is also intertwined with the mental health of the individuals enduring them. Depression, as frequent comorbidity in patients with CNCD, affects negatively their quality of life, functional capacity, and adherence to treatment, which can exacerbate the progression and worsen the prognosis of these health conditions. Besides, this two-way relation between depression and CNCD creates a vicious circle, given that the presence of one can increase the risk of developing the other.8,9

In the Colombian context, where the CNCD prevalence is on the rise, understanding the magnitude of the problem of depression in this population becomes an essential task. However, the accurate and valid measurement of the depression symptoms in chronically ill Colombians has been limited due to the lack of an adequate and validated instrument, specifically for this population.10

Bearing in mind that the occurrence of depression is quite frequent in chronic pathologies, it becomes necessary to have instruments for a comprehensive assessment of this disease. In scientific literature, scales like the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD)11; the Montgomery Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)12; the Yesavage Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS)13; Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI-II),14 the Depression Scale by the Center of Epidemiological Studies (CES-D),15 and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) have broadly proven their usefulness in evaluating this disorder.16

Of the instruments mentioned, the PHQ-9 has become a gold standard because it permit evaluating depression in valid, reliable, and rapid manner. Thereby, scientific literature reports its validation in different Latin American countries. In Chile, the Spanish version of the PHQ-9 was validated for use in primary medical care. This study revealed that the PHQ-9 was highly effective, with 92% accuracy to detect depression. It was compared with the Hamilton-D scale and demonstrated to be in line with the standards by the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (CIE-10) for depression. The PHQ-9 is apparently a very effective tool to identify depression symptoms in primary care settings in Chile.17

Likewise, in Brazil, with 447 participants (191 men and 256 women), the accuracy of the PHQ-9 to detect depression episodes was evaluated in the general population from Pelotas, Rio Grande do Sul. In this case, the threshold ≥9 showed 77.5% sensitivity and 86.7% specificity in continuous results. However, upon using the algorithm, sensitivity dropped to 42.5%, while specificity increased to 95.3%. The study suggests that the PHQ-9 is effective in detecting major depressive episodes, with the score version being more useful than the algorithm to trace the major depression disorder in the community.18

Also, in Brazil, a study was conducted on the PHQ-9 using the item response theory (IRT). Said study discovered that the different items of the questionnaire had varying discrimination levels, from moderate to high. Items about thoughts of self-harm and death showed better discrimination capacity, while the item related to feeling depressed was less discriminative. The study supports using the PHQ-9 in rural zones of Brazil due to the progress offered by the IRT in analyzing depression detection tools.19

In Argentina, a study sought to validate and adjust the PHQ-9 to establish levels of severity in depression. It analyzed 169 patients with a mean age of 47.4 years, with 60.4% being women. The adapted PHQ-9 showed high internal consistency (α=0.87) and positive correlation with Beck's Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II) (r=0.88, p<0.01). The Argentine version of the PHQ-9 demonstrated validity and reliability to assess the severity of the depression symptoms.20

Also, in Chile, the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2) was used to detect depression symptoms in patients with diabetes or hypertension in Primary Health Care (PHC). It studied 94 participants with a mean age of 64 years, mostly women (73%). By comparing the PHQ-2 and PHQ-9, a constant relation was noted among its scores, without loss of connection. Upon using a cut-off score of 3 in the PHQ-2, it managed to better identify the PHQ-9 scores. Both versions showed a strong positive correlation (r=0.87). The PHQ-2 was effective in detecting depression symptoms under these conditions, suggesting the need to further evaluate with the PHQ-9 those obtaining three or more points in the PHQ-2.21

Likewise, in Peru, the PHQ-9 was investigated in medical students. Here, it was found that the questionnaire had good internal consistency (α=0.903). When evaluating distinct PHQ-9 models through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), the bifactor model (with general, somatic, and cognitive-affective factors) exhibited an acceptable fit (χ2=26.451, p=0.067; CFI=0.991; GFI=0.969; RMSEA=0.056). The PHQ-9 turned out to be a valid instrument for medical students, highlighting that the two-factor model adjusted best according to this analysis.22

In Ecuador, the Spanish version of the PHQ-9 was evaluated to measure depression symptoms. It was found that the one-dimensional model adjusted best and that the questionnaire evaluates both sexes similarly. Said evaluation showed good internal consistency throughout the sample and in subgroups by gender. Additionally, it demonstrated solid relations with similar measurements and moderate with others. In conclusion, the PHQ-9 seems useful to detect depression symptoms in the Ecuadorian public health system, given its good characteristics and validity.23

In Brazil, a study was conducted to validate the use of the PHQ-9 questionnaire in public PHC to detect depression symptoms. The study found significant correlation between the Hamilton (HAM-D) scales, indicating the validity of the PHQ-9 in detecting these symptoms. Thus, it was concluded that this questionnaire can be useful for qualified professionals in the public health network, especially in primary care, facilitating early diagnosis and timely detection of depression in the population.24

In the national setting, the PHQ-9 was used to detect depression symptoms in students from the health sciences. Thus, 541 participants were analyzed with a mean age of 20.18 years; 63.77% were women. In this sense, 27.3% prevalence was found for clinically significant depression symptoms. The PHQ-9 showed a two-factor model that explained 42.80% of the total variance, with items varying in their explanatory power. The reliability coefficients were solid (α=0.830; ω=0.89). The PHQ-9 was a valid and reliable tool to identify depression symptoms in students from the health sciences in this specific university.25

In turn, research was performed to confirm the validity of the PHQ-9 in also detecting depression symptoms in students from the health sciences. The scale's nine items resulted essential to assess depression symptoms in this population, showing a content validity coefficient (CVC) of 1. Linguistic adjustments were made in the items, considering the observations by the experts and from the discussion group. The study validated the PHQ-9 as an adequate tool to assess depression symptoms in these students, deeming essential its items and making adjustments for its comprehension and relevance.26

The aforementioned evidence demonstrates that, despite the existence of diverse evaluations of the psychometric properties of the PHQ-9 questionnaire to measure depression, the scientific literature has yet to identify a validation of the questionnaire in Colombian population with chronic diseases that can be used in diverse clinical, health, and research contexts. In addition, the antecedents indicate that different factor structures have demonstrated an adequate fit to the data, both a one-dimensional structure and multidimensional structures.

Thereby, this research gains vital importance, in as much as the validation of an instrument to measure depression symptoms in chronically ill Colombians will permit early and accurate detection of depression in this population, which will facilitate timely and adequate intervention.

In addition, the considerable burden of illness associated with chronic diseases, which is increased when patients have symptoms related to depression. Validation of the PHQ-9 in chronically ill patients is required, considering three points of view: psychometric, epidemiological and clinical. Psychometric, because the instrument has a differential behavior in clinical and non-clinical samples, as evidenced in the scientific literature. Epidemiological, because the prevalence of depression is high in Colombia, and the scientific literature has shown that it is high in people with CNCD. Clinical, because patients with CNCD who also suffer from depressive symptoms, are affected in their adherence to treatment for CNCD, and suffer exacerbation of their chronic symptoms.

This study sought to examine the evidence of content, construct, and convergent validity and internal consistency of the PHQ-9 in a sample of chronically ill Colombians. It is expected for these research results to contribute significantly to improving the quality of life and overall wellbeing of the chronically ill in Colombia.

MethodDesignA quantitative methodological study27 was carried out, which collected information for the psychometric analysis of the instrument's structure.

Population and sampleThe study population included adult chronically ill patients, diagnosed with a chronic non-communicable disease, and whose diagnosis was made two years ago or more. The study excluded those chronically ill due to the following conditions and, thus, not subjected to exposure under study: with remission of symptoms of two years or more; those who could not legally represent themselves; and those with cognitive degenerative disease. A minimum sample size of 90 participants was estimated to be adequate for the statistical procedures to be implemented, based on Naeem's criteria,28 which establishes 10 observations per item as acceptable; additionally, the recommendations for test construction were taken into account.29 Opportunity sampling was used.30 Finally, 575 chronically ill subjects participated from different regions of the country.

InstrumentAn ad hoc questionnaire was applied to evaluate the sociodemographic variables. The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used to evaluate the depression. The questionnaire's validation was implemented in general Colombian population conducted by Berrío et al.31 The PHQ-9 is a self-report measurement to evaluate the intensity of the depression symptoms within the previous seven days. It is an instrument to support the diagnosis of depression in clinical settings. The levels of severity of the depression symptoms that can be interpreted are: without depression (0–4), slight depression,5–9 moderate depression,10–14 moderately severe depression, and severe depression.20–27,32,33 It has high internal consistency (ω=0.89; 95% CI 0.88–0.90; α=0.88; 95% CI 0.87–0.89).31 Existence of a positive and robust correlation has been demonstrated between the PHQ-9 and the BDI-II (r=0.74; 95% CI 0.64–0.84).34 The instrument is of open access, according with that established by the International Test Commission (ITC). Regarding the scale's validity, sensitivity has been reported between 75% and 80%, and specificity close to 60%.35

The study also applied the emotional thermometer instrument, which is part of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network's American guideline on discomfort management,36 through a numerical scale from 0 to 10 and measures the global evaluation of emotional discomfort experienced by patients. Also, the Anxiety Scale (GAD-7) was used to detect generalized anxiety symptoms37; and the Colombian version of the Self-Care Assessment Scale Revised (ASA-R), which is a widely used scale in the health setting globally to assess individual skills in self-care practices,38 to perform the convergent validity analysis.

ProcedureParticipants were contacted through databases provided by Red Salud, Armenia (Quindío), via telephone calls to gain access to the population from this department. Also, students linked to research groups were involved in this project and, nationally, students involved with the DELFÍN program, as well as a research aide from the department of Antioquia; carrying out physical and virtual applications.

When the application of the instruments was online, data were gathered through Google Forms; the researchers’ institutional e-mail was used to provide information to the participants about the purpose of the study, ensure their informed consent to participate in it and the instrument's URL.

Participation was voluntary and responses were gathered anonymously after signing the informed consent form. The research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at Corporación Universitaria Empresarial Alexander von Humboldt, in strict compliance with regulatory requirements by the Helsinki Declaration,39 which describes the fundamental ethical principles for research with humans.

Strategy to analyze informationTo analyze the instrument's content validity of the instrument, the study consulted with three experts with psychometric and clinical knowledge, research trajectory and experience, and lack of conflicts of interests. Each one registered their perception about the criteria of relevance, clarity, accuracy and comprehension of the items.40,41

These data were analyzed with Aiken's V coefficient and reported with its corresponding 95% confidence interval.42 To analyze construct validity, the instrument's factor structure was determined, first, through an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and, thereafter, through CFA. For the EFA, the extraction method used was that of maximum likelihood with oblique rotation; for the selection of the number of factors, the parallel analysis method was used.43 For the CFA, the univariate and multivariate normality were evaluated and correlations of test items were calculated.44,45 Likewise, to evaluate the fit of the model obtained with the CFA, absolute, incremental, and parsimony adjustment measures were used.44,46 To analyze the test's convergent validity, correlations were calculated with the total scores of the scales, through Spearman–Brown's rho correlation coefficient. Finally, the internal consistency of the entire questionnaire was analyzed based on McDonald's Omega Coefficient.47 The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 29 and JASP version 0.18.0.0.0 were used for statistical analysis.

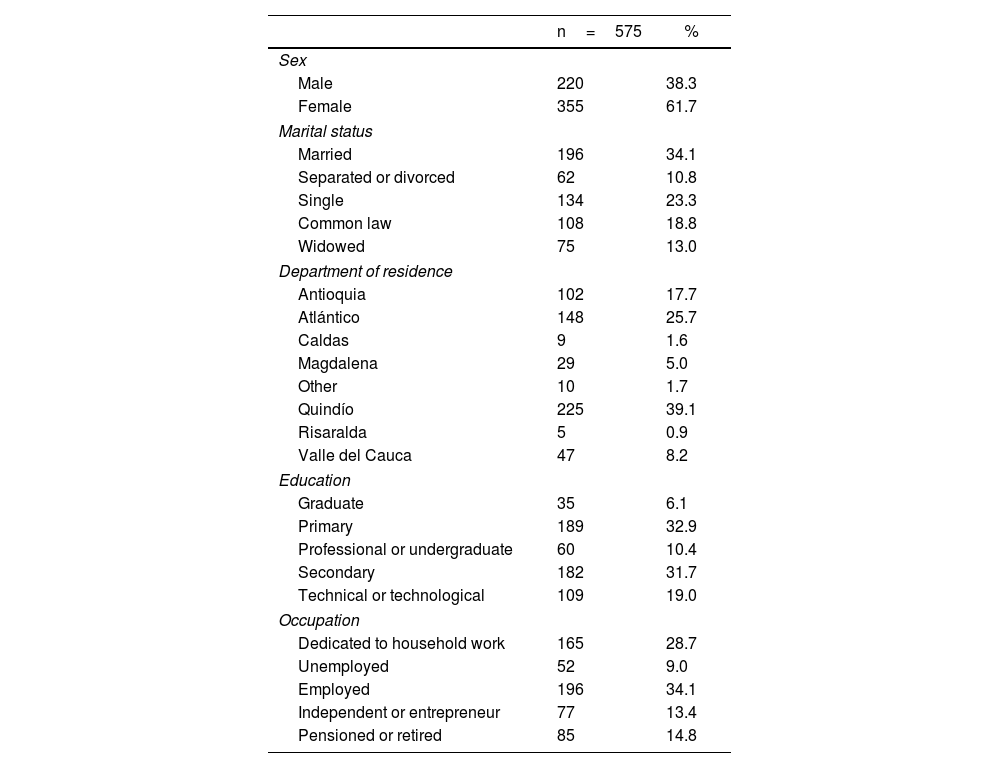

ResultsThe study had participation by 575 adult individuals, of which 355 are women (61.7%) and 220 men (38.3%), with a mean age of 55 years (RIC=26); 34.1% of those evaluated are married and 34.1% are employed. Higher participation was evidenced in the department of Quindío with 39.1%, followed by Atlántico with 25.7%. With respect to level of education, 32.9% completed primary school and 31.7% secondary school (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characterization of the sample.

| n=575 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 220 | 38.3 |

| Female | 355 | 61.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 196 | 34.1 |

| Separated or divorced | 62 | 10.8 |

| Single | 134 | 23.3 |

| Common law | 108 | 18.8 |

| Widowed | 75 | 13.0 |

| Department of residence | ||

| Antioquia | 102 | 17.7 |

| Atlántico | 148 | 25.7 |

| Caldas | 9 | 1.6 |

| Magdalena | 29 | 5.0 |

| Other | 10 | 1.7 |

| Quindío | 225 | 39.1 |

| Risaralda | 5 | 0.9 |

| Valle del Cauca | 47 | 8.2 |

| Education | ||

| Graduate | 35 | 6.1 |

| Primary | 189 | 32.9 |

| Professional or undergraduate | 60 | 10.4 |

| Secondary | 182 | 31.7 |

| Technical or technological | 109 | 19.0 |

| Occupation | ||

| Dedicated to household work | 165 | 28.7 |

| Unemployed | 52 | 9.0 |

| Employed | 196 | 34.1 |

| Independent or entrepreneur | 77 | 13.4 |

| Pensioned or retired | 85 | 14.8 |

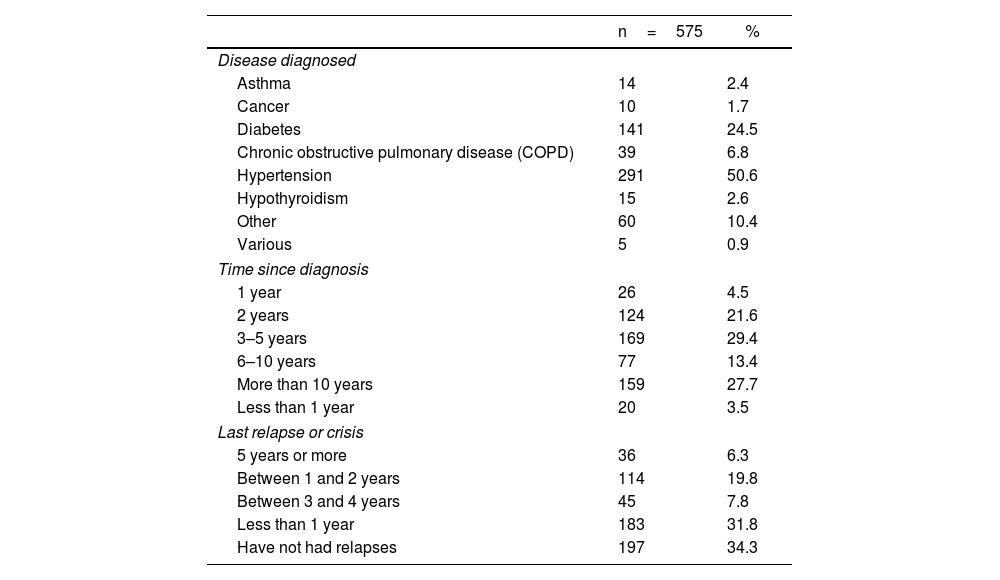

With respect to chronic diseases, 75.1% of the sample has been diagnosed with hypertension or diabetes; 29.4% of the patients were diagnosed 3–5 years ago, approximately, and 34.3% report not having had relapses or crisis (Table 2).

Characterization of chronically ill Colombians.

| n=575 | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Disease diagnosed | ||

| Asthma | 14 | 2.4 |

| Cancer | 10 | 1.7 |

| Diabetes | 141 | 24.5 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | 39 | 6.8 |

| Hypertension | 291 | 50.6 |

| Hypothyroidism | 15 | 2.6 |

| Other | 60 | 10.4 |

| Various | 5 | 0.9 |

| Time since diagnosis | ||

| 1 year | 26 | 4.5 |

| 2 years | 124 | 21.6 |

| 3–5 years | 169 | 29.4 |

| 6–10 years | 77 | 13.4 |

| More than 10 years | 159 | 27.7 |

| Less than 1 year | 20 | 3.5 |

| Last relapse or crisis | ||

| 5 years or more | 36 | 6.3 |

| Between 1 and 2 years | 114 | 19.8 |

| Between 3 and 4 years | 45 | 7.8 |

| Less than 1 year | 183 | 31.8 |

| Have not had relapses | 197 | 34.3 |

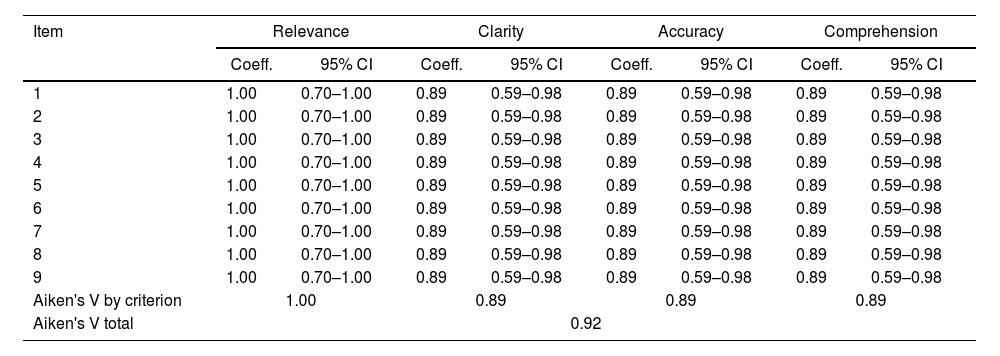

The content validity analysis calculated Aiken's V coefficient and its respective confidence interval, from the evaluation by the three expert judges, who provided their concepts with respect to relevance, clarity, accuracy, and comprehension – according with general recommendations for the area. Aiken's V coefficient evidenced substantial agreement among the experts about the content validity of the items making up the scale (0.92) (Table 3).

Aiken's V for the scale's items.

| Item | Relevance | Clarity | Accuracy | Comprehension | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coeff. | 95% CI | Coeff. | 95% CI | Coeff. | 95% CI | Coeff. | 95% CI | |

| 1 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.00 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 |

| 2 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.00 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 |

| 3 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.00 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 |

| 4 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.00 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 |

| 5 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.00 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 |

| 6 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.00 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 |

| 7 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.00 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 |

| 8 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.00 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 |

| 9 | 1.00 | 0.70–1.00 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 | 0.89 | 0.59–0.98 |

| Aiken's V by criterion | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.89 | 0.89 | ||||

| Aiken's V total | 0.92 | |||||||

Coeff.=Aiken's V coefficient.

Regarding construct validity, according with the sampling adequacy tests, it was concluded that the polychoric correlation matrix was susceptible to being analyzed through factor analysis (FA), while we found that there are common factors among the items of the scale (KMO=0.92) and it was not an identity matrix (β=4222.97; p<0.001).

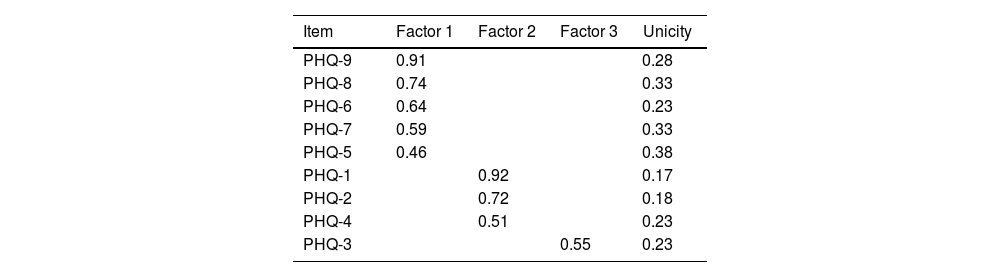

Hence, based on the parallel analysis and the sedimentation graph, three factors were extracted, through the ordinary least-squares method, combined with the Oblimin rotation method, recommended in the bibliography due to offering interpretable factorial structures and permitting association among factors.29 The EFA results are shown in Table 4.

To determine the factor structure with the best fit to the data, four factor models described in the literature were compared.48 Model 1 is composed of the nine items of the PHQ-9 and represents a unidimensional conceptualization of the construct; Model 2 is composed of a cognitive/affective factor composed of six items (Items 1, 2, 6–9) and a somatic factor, composed of three items (Items 3–5); Model 3 is a two-factor model composed of four cognitive/affective items (Items 1, 2, 6, 9) and five somatic items (Items 3–5, 7, 8). Finally, Model 4 is a bifactor model that includes both a general factor and the two factors described for Model 2.

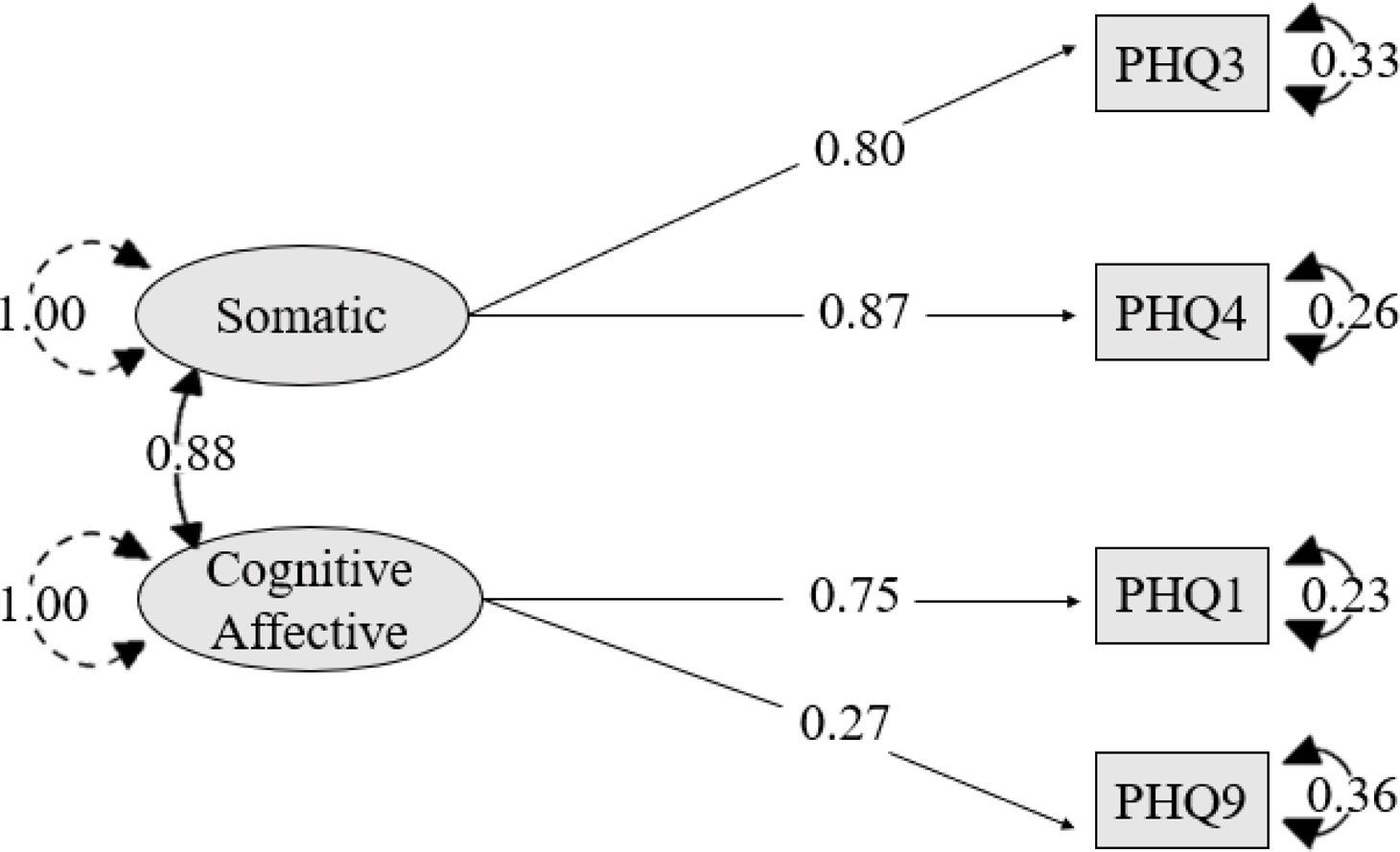

Regarding the CFA, the factor structure with the best fit to the data was the bifactor model composed by a cognitive/affective factor with items 1 and 9, and a somatic factor with items 3 and 4 (Fig. 1). We removed items with lower factor loadings to increase the goodness-of-fit of the model.

The model evidenced adequate incremental goodness-of-fit indexes, like chi-square factor model (χ2=0.80; gl=1; p=0.37), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) (0.00), standard root mean residual (SRMR) (0.004), and the goodness-of-fit index (GFI) (1.00). With respect to the absolute fit, the study evaluated the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) (1.00), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) (1.00), Normalized Fit Index (NFI) (1.00), Incremental Fit Index (IFI) (1.00), Non-Normalized Fit Index (NNFI) (1.00), Relative Fit Index (RFI) (0.99), and the Relative Non-Centrality Index (RNI) (1.00). Regarding the parsimony fit, the study evaluated the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (5115.08), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (2171.69), Parsimony Normalized Fit Index (PNFI) (0.17), and the Sample Size Adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (SSABIC) (5130.42).44–46,49–52

Thereafter, using Spearman–Brown's rho correlation coefficient, analyses revealed direct and statistically significant correlations between the total score of the PHQ-4 and the other scales evaluated, evidencing a correlation of depression with the emotional thermometer (r=0.540, p<0.001), and anxiety (r=0.660, p<0.001); with respect to the self-care scale, an inverse correlation (r=−0.142, p<0.001) was found.

Finally, the full questionnaire's reliability was analyzed through McDonald's Omega coefficient (after removal of items),47 which showed high internal consistency (ω=0.83).

DiscussionIn Latin America, the version in Spanish of the PHQ-9 instrument17,21,23,24,26 has been validated in different populations for some years. These validations have evidenced the instrument's versatility to contribute with the growing need to identify depression symptoms rapidly and generate timely interventions in each context. The aim of this research was to know the psychometric behavior of the PHQ instrument in users with chronic non-communicable diseases (CNCD) in Colombia, given that this instrument offers advantages for open access and self-administered rapid, valid screening.

The relevance, clarity, accuracy, and comprehension of the items of the PHQ scale were measured with Aiken's V coefficient (0.92) and indicate appropriate content validity,42 as evidenced in other studies where the nine items have Aiken's V indices >0.80, in university population53 and in patients with HIV (0.93).54

With regards to the correlations with the anxiety scales and the emotional thermometer, a positive statistically significant correlation with the PHQ was evidenced; analogous to this, other studies support their convergent validity: correlation with Beck's Depression Inventory in adolescents,54,55 with the Hamilton-D Scale in criminal police,24 in adult PHC users with the PHQ-2 short form and the HADS-D Scale,54–56 and in adult outpatient population, with different degrees of depression, through Beck's Depression Inventory (BDI-2),20 showing a positive statistically significant correlation among all these instruments and the PHQ. Moreover, application of the ASA-R scale revealed an inverse correlation with the PHQ (r=−0.142, p<0.001). No other research reports in scientific literature the correlation of any PHQ version with the emotional thermometer or any version of the ASA scale.

The factor analysis showed that there are common factors among the items of the scale, given that KMO values close to 1 generally indicate that a Factor Analysis can be useful with the data (0.92).26 Just as that reported by Huarcaya in 2020,22 Cassiani in 2018,26 and Doi in 2018,57 who performed analyses with unidimensional, bidimensional, and bifactor models, this study found that the factor structure with best fit to the data was the bifactor model; comprised by a somatic factor and a cognitive/affective factor, where the items that best assess the construct of depression and most relevant are item 1 (low interest or pleasure) and item 9 (suicidal thoughts), different from that found in university students in Peru, where items 2 (feeling down) and 6 (feelings of worthlessness) were the most relevant. Moreover, in this same population, in the somatic factor, the most-important item was 4 (fatigue), while the least important was 3 (problems sleeping).22 In this study, items 3 and 4 (Fig. 1), were the most relevant, such as that reported in the research in users of the Ecuadorian public health system where the most outstanding items were 3, 4 and 5.23

Finally, an adequate internal consistency value was obtained with McDonald's Omega Coefficient (ω=0.83). Other studies show quite similar internal consistency in users from PHC centers in Chile, where they also used Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient. In this case, both indicators (Omega and Alpha) were high: 0.896 and 0.891, respectively.58 Further, the instrument's internal consistency in adults, PHC users in Colombia, was 0.81 with McDonald's Omega Coefficient and 0.80 with Cronbach's alpha; this confirmed good consistency.59 Similarly, with patients from a hospital in Ecuador, the scale's reliability was α=0.852 and ω=0.855.23 Lastly, with different populations, such as students from health sciences, values of 0.89 were noted with McDonald's Omega.26

ConclusionsThis study demonstrated that the reduced version PHQ-4 questionnaire in Spanish is an instrument with adequate psychometric properties to apply in individuals with non-communicable chronic diseases in Colombia; thus, it can facilitate and improve detection, classification, and follow up of depression signs, which are often not detected during consultations and controls carried out by health staff. In addition, the brevity, easy comprehension, and self-completion of the PHQ-4 instrument are conducive to timely interventions, whether in prevention or treatment of depression in this population.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.