Problematic Internet use has become a growing problem worldwide; several factors, including personality, play an essential role in understanding this disorder. The Big Five personality traits and their association with problematic Internet use were examined in a large and diverse population.

MethodsA survey was applied to a total of 1,109 adults of working age. Each answered the Big Five Inventory and the Internet Addiction Test.

ResultsProblematic Internet use was found in 10.6% of them (n=112). The personality traits extraversion and openness to experience were significantly associated with those with the disorder. With adjustment models, a positive association was found between these traits and being single and higher education.

ConclusionsThis study represents the largest of its kind in the Spanish-speaking population, highlighting the importance of recognising the factors involved in problematic Internet use.

El uso problemático de internet es un problema creciente en todo el mundo; múltiples factores, como la personalidad, tienen un papel esencial en la comprensión de esta entidad. Los 5 grandes factores de personalidad y su asociación con el uso problemático de internet se evaluaron en una población grande y diversa.

MétodosSe aplicó una encuesta a un total de 1.109 adultos en edad productiva. Cada uno contestó el Inventario Big Five y el Internet Addiction Test.

ResultadosSe encontró uso problemático de internet en el 10,6% de ellos (n=112). En cuanto a rasgos de personalidad, la extroversión y la apertura a experiencias se asociaron significativamente con el uso problemático. Con modelos de ajuste, estos rasgos tuvieron una asociación positiva con no tener pareja y una educación superior.

ConclusionesEste estudio representa el más amplio de su tipo en población hispanohablante y destaca la importancia de reconocer los factores que intervienen en el uso problemático de internet.

Internet addiction was first studied in the 1990s by Kimberly Young, who developed criteria based on gambling disorder.1 People with problematic Internet use (PIU), or Internet addiction, have a marked interference in their daily functioning, loss of control of the behavior, distress, conflicts around its use, preoccupation about being online, and need to increase the time spent online.2,3 Young described in 1998 that 46% of problematic Internet users tried unsuccessfully to cut down their time online, returning to their previous use after experiencing intense cravings, even if they knew the consequences of continuing the behavior.4,5

PIU is commonly comorbid with affective disorders, anxiety, and any other addictive disorders, directly altering the productivity of those who suffer from it.6-10 Other relevant issues have also been linked to PIU, such as loneliness, depression, low self-esteem, and social anxiety.11–14

The Internet's addictive nature seems to be related to impulsivity and less executive control, both necessary in decision-making tasks.15,16 The most common personality profiles described in PIU show high expression of anger, novelty-seeking, neuroticism, harm avoidance, reward-dependence, low cooperation, psychoticism, impulsivity, reduced empathy, and low self-esteem.6,9,15

McCrae and Costa developed the Big Five factors of personality taxonomy in order to explain the relationships between personality traits. The five factors are extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experience. Each of these factors consists of a bidirectional trait, which can be more or less present in an individual.17

Extraversion portrays a talkative, assertive sociable person. Agreeable individuals are described as cooperative, trusted, altruist, and sensitive. Conscientiousness is related to being responsible, organized, and trustable. Neuroticism trait shows an anxious, tense person, prone to negative affections. People open to experience are creative, original, open-minded, and flexible.17

People predisposed to addictions (behavioral or substance-related) tend to have higher scores on neuroticism and low on conscientiousness. Each addiction, culture, age, education, and other population-specific factors weigh in on how the rest of the factors behave.5,18,19

Associations between the Big Five Traits and Internet use tend to be diverse according to different perspectives. For example, Hamburger found that extraversion is positively related to leisure activities online, and neuroticism negatively relates to information services use.20. A different research in university students showed a negative relation between conscientiousness and time spent online for leisure activities and a positive correlation with the same trait and its use for academic purposes.21 Cortés reported that 9.7% of their population had PIU, with a profile of high neuroticism and low agreeableness and conscientiousness.22 In Kuss's research, neuroticism was the strongest predictor of Internet addiction, followed by low agreeableness.23 Related studies on PIU and smartphone use disorder have similar findings, with stronger associations with high neuroticism and low conscientiousness.24

Typical characteristics of gambling disorder and other addictions are also seen in PIU, such as personality traits and sociodemographic characteristics. The Big Five taxonomy is a valuable tool to determine common features in those at risk.9,15,18

According to previous research, we hypothesized that those with PIU would have higher scores in neuroticism in our population, representing a risk factor for PIU. Additionally, we intended to describe other factors associated with PIU, such as the type of use they give to the Internet and their demographic characteristics.

MethodsParticipants and proceduresThe present study was a cross-sectional online questionnaire survey in Mexico City, previously approved by the institute's ethical committee. The sample consisted of 1109 individuals of productive age (20 to 50 years old). The mean age was 26.53±0.22. The convenient sample was recruited through a public announcement and e-mail invitation. The e-mail contained a link where people were invited to answer the Personality traits and their association with problematic Internet use survey. Informed consent was acquired when each participant received the questionnaire online. After participants were fully instructed and acknowledged the anonymity and de-linkage principle together with other ethical considerations, they carried on fulfilling the questions online based on their willingness. Each individual completed two main questionnaires: the Internet Addiction Test (IAT) and the Big Five Inventory (BFI). Additionally, the respondents were asked about sociodemographic factors and the frequency they used the Internet for: information, e-mail, social media, gaming, shopping, adult content, and entertainment.

MeasuresIAT. The test comprises 20 items, answered with a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not applicable) to 5 (always). The IAT is a valid cosmopolitan one-factor instrument for measuring Internet addiction.25 This test is validated26 in the Mexican population with a Chronbach's alpha of .913. The test includes concepts such as loss of control, negligence in daily life, cognitive salience, negative consequences, mood changes, and deception. The participants that obtain a score between 20 and 49 points are considered average users; those who score between 50 and 79 points belong to the category of problematic Internet use (PIU), and those who score 80 points or over are considered to have an addictive Internet use.27

BFI. John et al.17 developed this test to assess the Big Five personality trait domains: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness to experiences. It is a brief inventory with 44 short phrases that the respondent answers on a five-point rating scale, ranging from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). The test is validated28 in the Mexican population with α=.72

Demographics and Internet use habits. The participants were asked to fill out demographic information including gender, age, marital status (whether they have or not have a partner), education level (less of, or 9 or more years of education), presence or absence of comorbid disease (yes or no), and alcohol, tobacco, and another drug use (yes or no). They were also requested to fulfill the following assessment on Internet use habits: information search, e-mailing, social networking, gaming, shopping, adult content, and entertainment. The questions were presented on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (never) to 5 (always).

Statistical analysisStatistical software Stata 14 was used. Descriptive statistic data were obtained, including totals, proportions, frequencies of the categorical variables, and the measures of central tendency and dispersion of the numerical variables. Before carrying out the association analysis, it was verified that the numerical variables complied with a normal distribution through qq plots. For the association analysis between the IAT score and each of the scores of the different personalities obtained in the BFI, linear regressions were carried out. Independent analysis was developed through regression obtaining coefficients (CF) for further developing an adjusted model including sociodemographic variables.

Dependent models were made taking the variables (BFI traits) that were significant in the linear regressions. Sociodemographic variables were used to adjust the models by adding those variables that contributed to the value of R2 through the sum of squares method and did not subtract statistical significance from the model. Statistically significant results were those that resulted in a score of P<.05.

ResultsSociodemographic informationA total of 1432 subjects participated in the study. Of those, 323 were excluded from the final sample: 74 were due to errors in completing the questionnaires, and 249 did not meet the age criteria (20 to 50 years of age). The final sample size was a total of 1109 subjects.

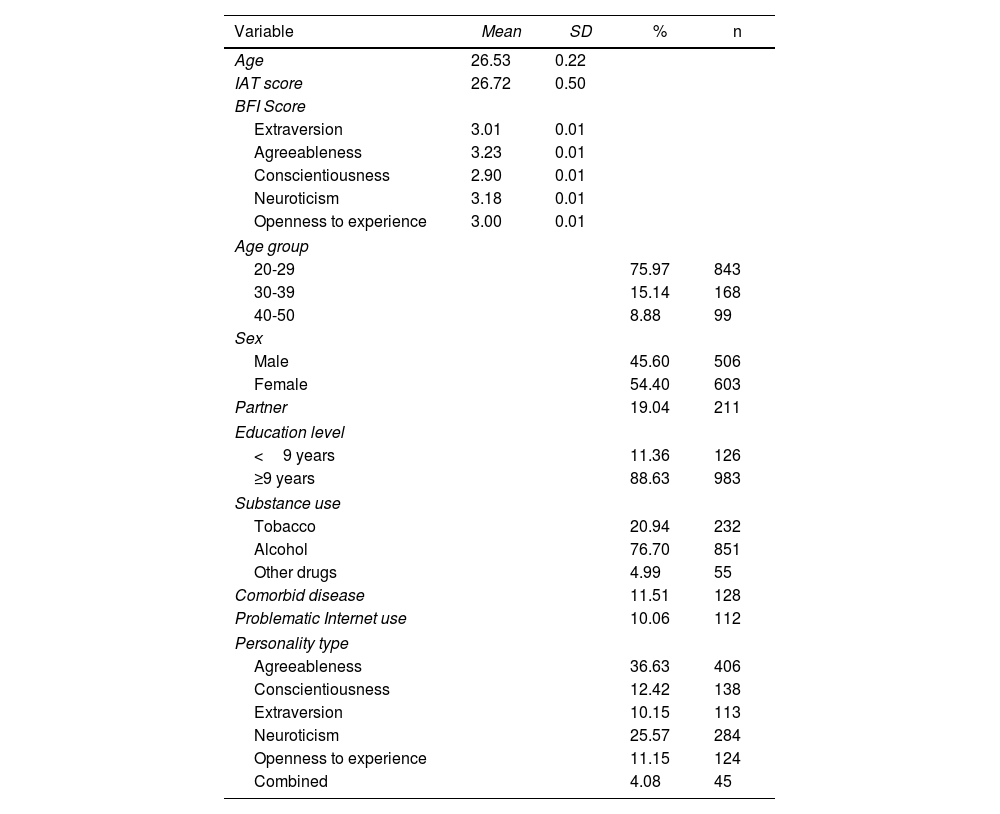

Table 1 shows the demographic variables. The study participants mainly involved 603 females (54.40%), and most of the sample (75.97%) were 20-29 years of age. Only 211 participants (19.04%) reported having a partner. Regarding education level, 983 (84.58%) completed 9 or more years of education. As for Internet use, 112 (10.06%) participants resulted in problematic Internet use.

Sociodemographic characteristics (n=1109).

| Variable | Mean | SD | % | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 26.53 | 0.22 | ||

| IAT score | 26.72 | 0.50 | ||

| BFI Score | ||||

| Extraversion | 3.01 | 0.01 | ||

| Agreeableness | 3.23 | 0.01 | ||

| Conscientiousness | 2.90 | 0.01 | ||

| Neuroticism | 3.18 | 0.01 | ||

| Openness to experience | 3.00 | 0.01 | ||

| Age group | ||||

| 20-29 | 75.97 | 843 | ||

| 30-39 | 15.14 | 168 | ||

| 40-50 | 8.88 | 99 | ||

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 45.60 | 506 | ||

| Female | 54.40 | 603 | ||

| Partner | 19.04 | 211 | ||

| Education level | ||||

| <9 years | 11.36 | 126 | ||

| ≥9 years | 88.63 | 983 | ||

| Substance use | ||||

| Tobacco | 20.94 | 232 | ||

| Alcohol | 76.70 | 851 | ||

| Other drugs | 4.99 | 55 | ||

| Comorbid disease | 11.51 | 128 | ||

| Problematic Internet use | 10.06 | 112 | ||

| Personality type | ||||

| Agreeableness | 36.63 | 406 | ||

| Conscientiousness | 12.42 | 138 | ||

| Extraversion | 10.15 | 113 | ||

| Neuroticism | 25.57 | 284 | ||

| Openness to experience | 11.15 | 124 | ||

| Combined | 4.08 | 45 | ||

BFI: Big Five Inventory; IAT: Internet Addiction Test; SD: standard deviation.

The means obtained of each personality trait in the BFI in the general sample are also shown in Table 1. When classified by these scores, 113 (10.15%) participants resulted with higher scores in extraversion, 406 (36.63%) with agreeableness, 138 (12.42%) with conscientiousness, 284 (25.57%) with neuroticism, 124 (11.15%) with openness to experience, and 45 (4.08%) resulted in combined traits.

Internet use habitsTable 2 presents the results from the descriptive analysis of Internet use habits. The most frequent uses of the Internet reported in the sample were: always information searching, 468 (42.16%); always social networking, 538 (48.50%); always e-mailing, 372 (33.54%); never adult content searching, 554 (49.95%); always entertainment, 434 (39.17%); never gaming, 295 (26.56%), and almost never shopping (25.48%).

Internet use habits. Descriptive analysis.

| Variable | % | n | Variable | % | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Information searching | Adult content | ||||

| Never | 1.63 | 18 | Usually | 5.98 | 66 |

| Almost never | 5.08 | 56 | Almost always | 2.99 | 33 |

| Almost usually | 8.61 | 96 | Always | 1.36 | 15 |

| Usually | 17.14 | 190 | Entertainment | ||

| Almost always | 25.39 | 282 | Never | 1.09 | 12 |

| Always | 42.16 | 468 | Almost never | 4.99 | 55 |

| Social networking | Almost usually | 10.79 | 120 | ||

| Never | 0.91 | 10 | Usually | 17.32 | 192 |

| Almost never | 3.99 | 44 | Almost always | 26.65 | 296 |

| Almost usually | 7.07 | 78 | Always | 39.17 | 434 |

| Usually | 16.23 | 180 | Gaming | ||

| Almost always | 23.30 | 258 | Never | 26.56 | 295 |

| Always | 48.50 | 538 | Almost never | 22.76 | 252 |

| E-mailing | Almost usually | 17.77 | 197 | ||

| Never | 1.36 | 15 | Usually | 14.51 | 161 |

| Almost never | 5.17 | 57 | Almost always | 9.07 | 101 |

| Almost usually | 10.24 | 114 | Always | 9.34 | 104 |

| Usually | 20.49 | 227 | Shopping | ||

| Almost always | 29.19 | 324 | Never | 15.32 | 170 |

| Always | 33.54 | 372 | Almost never | 25.48 | 283 |

| Adult content | Almost usually | 25.02 | 278 | ||

| Never | 49.95 | 554 | Usually | 19.49 | 216 |

| Almost never | 26.47 | 294 | Almost always | 9.61 | 107 |

| Almost usually | 13.24 | 147 | Always | 5.08 | 56 |

In Table 3, the results of linear regressions are provided. The personality traits that resulted in a significant association with the IAT score were extroversion (CF=8.27; P<.001) and openness to experience (CF=11.73; P<.001). Both personality traits resulted in a positive association.

Linear regressions between IAT scores and BFI scores.

| BFI traits | CF | SD | P<.05 | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agreeableness | 0,37 | 1,42 | .793 | –2,42 | 3,16 |

| Extraversion | 8,27 | 1,63 | <.001 | 5,07 | 11,47 |

| Conscientiousness | 2,40 | 1,26 | .058 | –0,08 | 4,87 |

| Neuroticism | 1,71 | 1,56 | .272 | –1,35 | 4,77 |

| Openness to experience | 11,73 | 1,25 | <.001 | 9,26 | 14,19 |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; BFI: Big Five Inventory; CF: coefficient; IAT: Internet Addiction Test; SD: standard deviation.

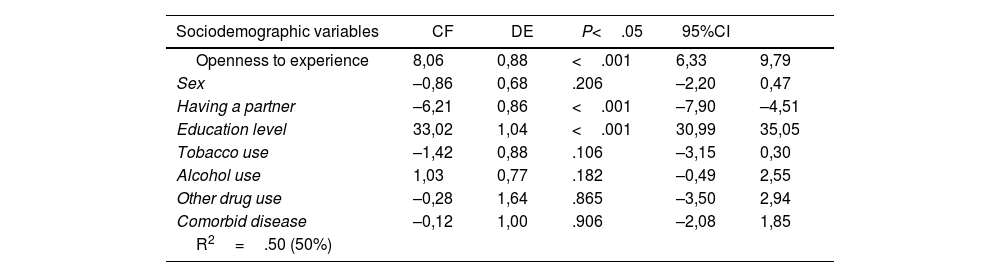

Two models were carried out, one adjusted with the personality trait of extraversion and the other with openness to experience. Both models were adjusted by sociodemographic variables.

In the model adjusted by extraversion (CF=8.06; P<.001), the variables having a partner (CF=–6.21; P<.001), and education level (CF=33.02; P<.001) resulted in statistical significance. Having a partner exhibited an inverse association with the IAT score, and education level presented a positive association in this model. The model had an R2 of .50 (50%) (Table 4).

Extraversion model adjusted by sociodemographic variables.

| Sociodemographic variables | CF | SD | P<.05 | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extraversion | 5,83 | 1,12 | <.001 | 3,64 | 8,02 |

| Sex | –0,68 | 0,70 | .329 | –2,04 | 0,69 |

| Having a partner | –6,01 | 0,89 | <.001 | –7,76 | –4,27 |

| Education level | 34,35 | 1,04 | <.001 | 32,31 | 36,40 |

| Tobacco use | –1,00 | 0,90 | .264 | –2,76 | 0,76 |

| Alcohol use | 1,25 | 0,79 | .114 | –0,30 | 2,79 |

| Other drug use | 0,68 | 1,67 | .683 | –2,59 | 3,96 |

| Comorbid disease | 0,17 | 1,02 | .865 | –1,83 | 2,18 |

| R2=.48 (48%) |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; BFI: Big Five Inventory; CF: coefficient; IAT: Internet Addiction Test; SD: standard deviation.

Table 5 shows the second model, adjusted by the openness to experience trait (CF=5.83; P<.001), the variables having a partner (CF=–6.01; P<.001), and education level (CF=34.35; P<.001) resulted in statistical significance. Having a partner displayed an inverse association with the IAT score, and education level presented a positive association in this model. The model had an R2 of .48 (48%).

Openness to experience model adjusted by sociodemographic variables.

| Sociodemographic variables | CF | DE | P<.05 | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Openness to experience | 8,06 | 0,88 | <.001 | 6,33 | 9,79 |

| Sex | –0,86 | 0,68 | .206 | –2,20 | 0,47 |

| Having a partner | –6,21 | 0,86 | <.001 | –7,90 | –4,51 |

| Education level | 33,02 | 1,04 | <.001 | 30,99 | 35,05 |

| Tobacco use | –1,42 | 0,88 | .106 | –3,15 | 0,30 |

| Alcohol use | 1,03 | 0,77 | .182 | –0,49 | 2,55 |

| Other drug use | –0,28 | 1,64 | .865 | –3,50 | 2,94 |

| Comorbid disease | –0,12 | 1,00 | .906 | –2,08 | 1,85 |

| R2=.50 (50%) |

95%CI: 95% confidence interval; BFI: Big Five Inventory; CF: coefficient; IAT: Internet Addiction Test; SD: standard deviation.

This study's primary purpose was to find associations between Big Five personality traits and PIU. There is very little research about this issue in our region. According to national statistics, 92% of people in Mexico tend to use the Internet at least once a week. However, there is not an accurate report of problematic Internet use and its risks.29

In our population, 10.6% had problematic Internet use, similar to the study by Cortés in Colombian subjects.22 Interestingly, we found that the PIU population was almost equally divided between males and females (48.5% were women); most research finds it predominantly male.1,19

PIU tends to prevail in adolescents and younger people, probably because of their knowledge and easiness of Internet use.6,30–32 Most of the samples in other studies tend to be performed in university students or adolescents, but ours was on adults in the general population with individuals up to 50-years old. However, most PIU individuals were 20 to 29 years old, which was expected as described in the literature.24,25 This group represents a vital economic force; PIU directly affects their productivity and implies possible comorbidities.

Regarding personality traits and PIU, we found openness to experience and extraversion to positively relate, meaning that these traits’ predominance correlates to higher IAT scores. These findings go against most studies that consider neuroticism the most correlated trait to PIU and reject our research's main hypothesis. Extraversion is usually considered to have a negative relation to PIU.33,34 While openness to experience varies from positive, negative, or no relation to PIU19,35

Extraverted individuals’ tendency to show assertive behaviors helps them achieve their goals and ease socializing.36 We could explain this trait as a determining factor for overusing social media or ways to communicate online in our population. It has been described that extraversion can positively affect excessive Internet use to ludic activities online.20 We believe that those with higher extraversion scores could use the Internet excessively for social media, commonly used in the younger adults, representing the most affected group in our population (75.97% of the total of participants).

Open individuals have high interest and curiosity levels; real-life and virtual settings can provide attractive opportunities to satisfy their interests, demonstrating why it represents the most variable trait in previous research. It is also a common trait found in those with excessive social media use.25 We believe that our population would profoundly satisfy their curiosity through the Internet, explaining this trait as a risk factor.19,36

In the models of both traits (openness to experience and extraversion), we found that being single and higher education level correlated to higher IAT scores. We consider that the Internet can help people socialize comfortably; it is also a medium for education or information searching, representing a higher use in this particular population.

Social networking, adult content search, entertainment, gaming, and shopping are well-known PIU risk factors, notably because of impulsivity and immediate rewards.4,37 While analyzing Internet use habits in the PIU group, we found that they used it more often for social networking and e-mail.

Social media is a common technological addiction, especially in younger individuals, and tends to be associated with openness to experience.30,38,39 E-mailing is an everyday practice for work and education; it makes sense that it is a regular practice in our population, notably since higher education correlated to higher IAT scores.

Yu Tian et al.40 recently published a study noting that Big Five personality traits, PIU, and maladaptive cognitions have a bidirectional and dynamic relationship, meaning that cognitions at the time of the study could affect how personality traits and the Internet use can correlate. Considering this, we could also explain why our findings were different than expected, being this an essential factor for future research.

Some limitations should be regarded in this research. First of all, being an online self-answered survey, some bias can be found, leaving it to the interpretation of each subject's answer to the questionnaires. Another limitation is that the type of Internet use was entirely subjective, without time measurements or a more standardized way to measure it. We did not consider eliminating online use for academic or work purposes, which can change the IAT and Internet use habits scoring. Future research should address these issues more profoundly, considering the use of the Internet in people with PIU.

Our study's main strength is the number of participants (being the largest to date in adults to our knowledge) and the inclusion of a more diverse group. Most studies are done on students or adolescents; in contrast, this study includes individuals with different education levels and 20 to 50 years of age. These factors imply that the results can be extrapolated to the general population.

ConclusionsThis research is the largest and most complete one in the Spanish-speaking population. We were able to recruit a larger sample, which extended to different ages, education levels, and communities. The results come in handy for future reference and noticing the at-risk population, helping to a better understanding and management of the disorder. It also contributes to the extensive study of PIU in hopes of a better implementation of prevention and treatment strategies for a growing problem in the actual society.

FundingsThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interestsNo competing financial interests exist.

The authors thank the participants in this study.