Since 1980, there have been known cases of childhood neuropsychiatric syndromes in the world and its concept has evolved with changes in the definitions in 1995 (PITANDs — paediatric infection-triggered autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders), 1998 (PANDAS — paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric syndrome associated with streptococci infection), 2010 (PANS — paediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome) and 2012 (CANS — childhood acute neuropsychiatric syndrome). Despite being known for more than 20 years, it is still an illness that often goes unnoticed by many health professionals.

ObjectiveTo sensitise the medical community about the identification of the disease and reduce the morbidity associated with a late diagnosis.

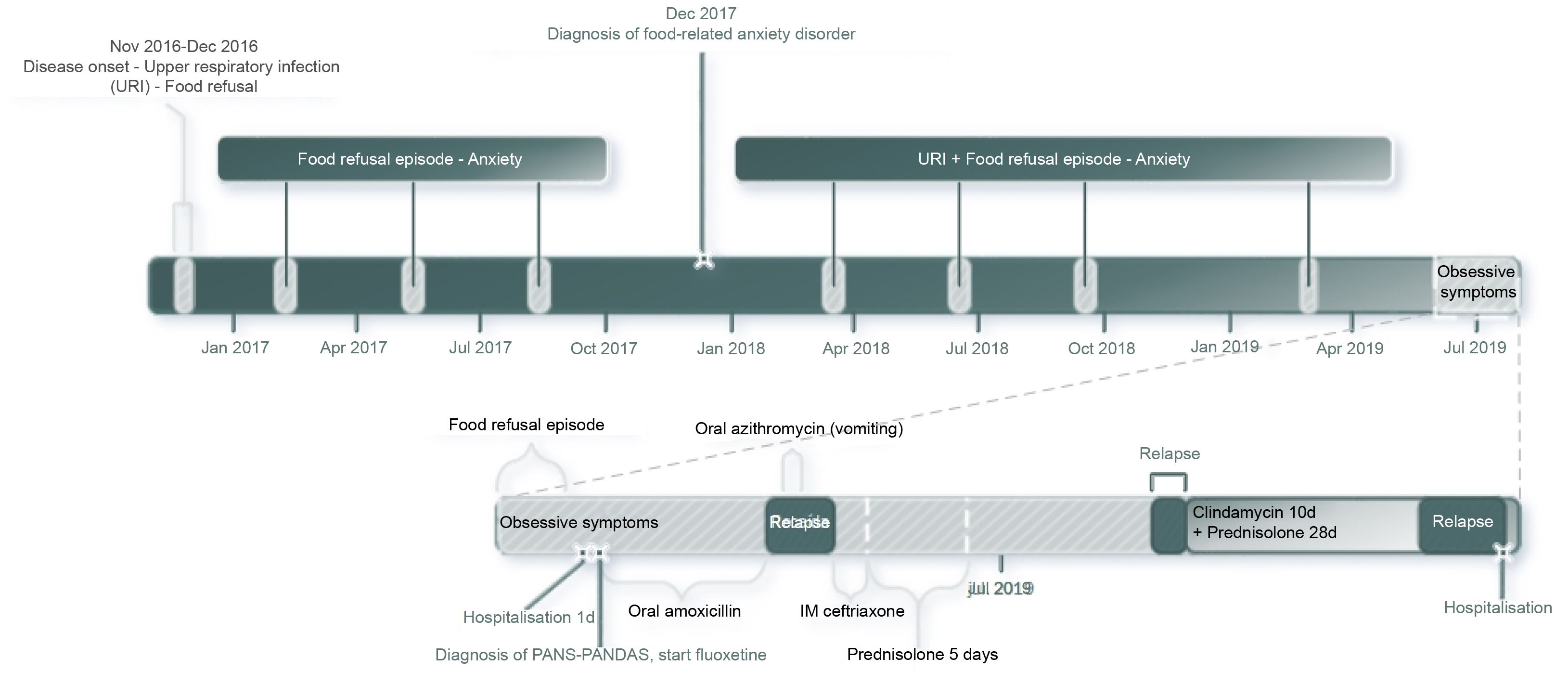

Clinical caseA 6-year-old schoolgirl brought to the emergency department due to her refusal to eat. In the hospital treatment, a clinical history was identified with PANS-PANDAS diagnostic criteria. She exhibited a relapsing-remitting clinical course, as described in the literature, with poor response to first-line treatments.

ConclusionsIn all school-age child presenting with obsessive compulsive disorder or eating disorders, with other symptoms or not, a possible link to PANS-CANS should be evaluated and ruled out.

Desde 1980 se conocen casos de síndromes neuropsiquiátricos infantiles en el mundo y su concepto ha evolucionado con cambios en las definiciones de 1995 (PITANDS: trastornos neuropsiquiátricos pediátricos autoinmunes precipitados por infección), 1998 (PANDAS: síndrome neuropsiquiátrico autoinmune pediátrico asociado con la infección por estreptococos), 2010 (PANS: síndrome pediátrico neuropsiquiátrico de inicio agudo) y 2012 (CANS: síndromes neuropsiquiátricos agudos de los niños). A pesar de que se conoce desde hace más de 20 años, aún es una enfermedad que suele pasar inadvertida para muchos profesionales de la salud.

ObjetivoSensibilizar a la comunidad médica acerca de la identificación de la enfermedad y disminuir la morbilidad asociada con un diagnóstico tardío.

Caso clínicoUna niña de 6 años consultó a urgencias por trastorno de rechazo alimentario. En el tratamiento hospitalario se identificó historia clínica con criterios diagnósticos de PANS-PANDAS. Mostraba un curso clínico recurrente-remitente, tal y como describe la literatura, con pobre respuesta a los tratamientos de primera línea.

ConclusionesEn todo niño en edad escolar que se presente con trastorno obsesivo compulsivo o trastornos alimentarios, con sin otros síntomas, se debe evaluar y descartar su asociación con PANS-CANS.

Since 1980, there have been known cases of childhood neuropsychiatric syndromes in the world but such syndromes have only been recognised as a nosological entity by the U.S. National Institute of Health (NIH) since 1995 (PITANDS: paediatric infection-triggered autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders). It was indicated at that time that these syndromes were a frustrated form of Sydenham's chorea since their prodromal symptoms include components of an obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).1 In 1998, Dr Swedo (member of the U.S. NIH and an elite worldwide expert in these syndromes) coined the term PANDAS (paediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections) and described a preschool age onset and a girl:boy ratio of 2.6:1.2 The greatest operative difficulty since then has been to show (and suspect) the association with infection given the high prevalence of streptococci at school age with asymptomatic infections. Defining when tics may be associated with PANDAS has also been hotly debated, apart from the fact that the definition excluded cases triggered by other infections.3–5 In response to this, in 2012, the 2010 NIH Consensus was published, which created the definition of PANS (paediatric acute-onset neuropsychiatric syndrome), in which tics are a secondary diagnostic criterion. Other categories of neuropsychiatric symptoms were included and their association with more microorganisms was considered.6 Finally, in 2012, Dr Singer came up with an even simpler definition at Johns Hopkins University, known as CANS (childhood acute neuropsychiatric syndromes), with less restrictive criteria.4 The evolution of the diagnostic criteria and their hierarchy is shown in Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria for childhood neuropsychiatric disorders.a

| PITANDS (1995) | PANDAS (1998) | PANS (2010) | CANS (2012) |

|---|---|---|---|

| All the following: | All the following: | Onset of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) or restrictive food intake and concurrent symptoms from at least 2 of the following 7 categories: | All the following: |

| [1] Onset between 3 years of age and start of puberty | [1] Presence of OCD or a tic disorder | [1] Anxiety (especially separation anxiety) | |

| [2] Must have had OCD and/or a tic disorder at some time | [2] Onset before puberty | [2] Emotional lability or depression | [1] Abrupt onset before 18 years of age |

| [3] Sudden onset of symptoms with remittent-recurrent pattern | [3] Remittent-recurrent pattern | [3] Irritability, aggression and/or severe oppositional behaviour | [2] OCD and/or |

| [4] Episodes must not be exclusively associated with stress and illness and suggest need for treatment modifications, lasting at least 4 weeks | [4] Temporarily associated with group A streptococcal infections at onset or during exacerbations | [4] Developmental regression | [3] Any of the secondary criteria: |

| [5] During OCD and/or tic exacerbations, must have abnormal neurological examination, often with adventitious movements | [5] Associated with neurological abnormalities such as motor hyperactivity or choreiform movements | [5] Worsening of academic performance related to attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or cognitive disorders (memory deficits) | a) anxiety |

| [6] Must have evidence (microbiological or clinical) of preceding infection | [6] Motor or sensory abnormalities (hallucinations, tics) | b) psychosis | |

| [7] Child may or may not continue to have symptoms between episodes | [7] Somatic signs and symptoms, such as sleep disturbance, enuresis or increased urinary frequency | c) developmental regression | |

| In addition, symptoms are not better explained by any other known neurological or medical condition | d) sensory hypersensitivity | ||

| e) emotional lability | |||

| f) tics | |||

| g) dysgraphia | |||

| h) clumsiness or hyperactivity | |||

| [4] May be monophasic or polyphasic |

Pathophysiologically, PANS is a primary and/or post-infectious autoimmune disease (influenza, mycoplasmas, Epstein-Barr virus, group A streptococci) affecting the basal ganglia.7 Diagnosis is by exclusion since PANS is clinically associated with a large number of conditions for which a differential diagnosis should be considered given that there is no specific biomarker.3,7 Treatment is based on psychotherapy, psychiatric drugs and antibiotic and immunomodulatory therapy.7,8

Here we will present the case of a school girl diagnosed with PANS-PANDAS in order to increase awareness within the medical community of identifying the disease and reducing morbidity associated with a late diagnosis.

CaseA 6-year-old school girl was brought to the emergency department due to refusing to eat for the last 5 days. She had suffered from food-related anxiety disorder for the last 2 years and was being clinically monitored by both the Psychiatry and Psychology departments. No psychiatric drugs had been prescribed.

Upon physical examination, she showed normal development (weight, 28 kg; height, 130 cm) with dry oral mucosa and no other physical abnormalities. The decision was made to admit her for rapid intravenous rehydration.

During another interview with her mother, a history of accelerated growth without early puberty and isolated episodes of headache with vomiting over the last 3 years was documented. As a result of this, a head CT scan without contrast was ordered to rule out a brain tumour. The scan showed normal encephalic structures and mucosal thickening of the right maxillary sinus.

Based on this result, the mother was interviewed for a third time and the possibility of PANS-PANDAS was considered. During the interview, it was discovered that, three months before, the girl had presented with upper respiratory symptoms, after which her anxiety symptoms got worse and obsessive symptoms appeared (she got up impulsively to tidy things away; she became very strict with her schoolwork and homework; she refused help because nobody else did things properly; she said she was going to be late for school all the time; she worried about being last in the class despite being the best; she erased and rewrote her school books, and she ordered all her toys according to size and/or colour). It was deemed that she met criteria for the disease and a semi-quantitative antistreptolysin-O (ASO) antibody test was ordered, which was negative. She was started on oral amoxicillin 90 mg/kg/day for 10 days.

She was assessed by Psychiatry, who observed anxious symptoms, low frustration tolerance, separation anxiety and signs of somatisation. Oral fluoxetine 8 mg/day and outpatient follow-up by Child Psychiatry was prescribed.

Over the following 24 h, her refusal of oral foods improved and she was therefore discharged. She completely regained her appetite and her anxious symptoms improved over the next 72 h. However, she relapsed one day after finishing the amoxicillin (10 days after discharge) and again refused to eat. She harmed herself (by pulling her own hair) and became anxious again. As a result of this relapse, oral azithromycin 12 mg/kg/day for 7 days was prescribed, but the girl refused to take the medication and made herself vomit. The next day (11 days after discharge), the treatment was changed to intramuscular ceftriaxone 50 mg/kg/day for 3 days. It was also documented that her mother and brother had recurrent pharyngotonsillitis, so they were started on oral azithromycin 500 mg/day for 5 days.

She was assessed by Paediatric Rheumatology the same day as she started ceftriaxone and it was determined that the disease had started 3 years before with an event of nausea and vomiting at night, which occurred during a respiratory infection (fever, rhinorrhoea and cough) that was treated with antibiotics, and this was associated with an anxious attitude. Since then, she has had similar episodes every 3–4 months, which have clearly been related to respiratory symptoms. She has also harmed herself (scratched herself with pencils, hit herself, pulled out her nails) often (3 times a week) during this exacerbation over the last 3 months. She was also found to have sleep-onset insomnia and short sleep duration (5 h), with episodes of frequent movements. Finally, unstructured, self-limiting visual and auditory hallucinations were documented for the 2 days prior to the appointment.

At the same assessment, it was also determined that her mother had antiphospholipid syndrome and her older brother had an avoidant restrictive food intake disorder at the age of 9.

Since the symptoms were consistent with PANS-PANDAS, prophylaxis treatment with intramuscular benzathine penicillin 600,000 IU/21 days was administered for 3 months.

The girl relapsed again with refusal to eat and self-harm after finishing ceftriaxone and was therefore prescribed prednisone 50 mg/day for 5 days, with which she gradually improved. After finishing this treatment, she remained partially functional for 2 weeks as the minor obsessive symptoms (tidying things away) persisted and she refused to go to school. Prescribing non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs was not considered given her history of allergy to ibuprofen.

At this time, 30 days after discharge, she returned to school, but after 2 days, she had symptoms of a cold and the separation anxiety reappeared so she had to stay home again. In view of this, oral clindamycin was prescribed for 7 days (30 mg/kg/day) on the recommendation of Paediatric Infectious Diseases to completely eradicate the streptococci, along with oral prednisolone for 4 weeks (starting dose 2 mg/kg/day with weekly tapering). She showed a clear improvement by the end of the second week and only the early-morning nausea persisted. She therefore returned to school for one week. She then got ill with cold-like symptoms and relapsed with food refusal and self-harming for five days, which resulted in dehydration and one day in hospital. She completed the 4-week cycle of prednisolone, without complete improvement and with relapse on completing the treatment, and suffered another food refusal episode that lasted 15 days, which the family treated at home.

Fluoxetine had to be suspended due to the onset of symptoms of hyperprolactinaemia (premature thelarche, mastalgia, hypertrichosis, adrenarche). Early puberty was suspected due to its intensity after 3 months of administration (August 2019). As a result, risperidone was prescribed but she did not tolerate it for more than 1 week due to headaches and vomiting. Moreover, no significant clinical response was observed.

Her family decided to remove her from follow-up by the research group 2 months after the last hospital admission (September 2019).

DiscussionFirstly, it is important to note the sequence of medical assessments performed for this case. The purpose of this is to increase awareness of the difficulties faced when diagnosing and treating PANS-PANDAS and its tendency to be characterised by frequent relapses. Fig. 1 is shown for teaching and clarification purposes.

It is interesting to note that children with OCD are not often diagnosed with PANS-PANDAS (prevalence of 1% for PANDAS, 3% for PANS and 1% for cases meeting both sets of criteria).5 Inclusion in this latter category is of great interest for the case presented above.

One point to highlight from the above case is the fact that the family history documented antiphospholipid disease and one case of an eating disorder, which reflects the vulnerability of these patients, of autosomal recessive inheritance, reflected as autoimmune diseases in mothers (including antiphospholipid syndrome), with up to a 10-fold risk increased of OCD and tics in first-degree relatives, and reports of multiple neuropsychiatric conditions in the family (including eating disorders). This may be considered an auxiliary diagnostic criterion.2,3,9,10

The infection history of the mother and brother is also important because it reflects the patient's susceptibility to, and potential sources of, infection.3

Prior to starting treatment, it is important to always perform a thorough but individualised evaluation, including a full medical history, comprehensive anamnesis (Table 2) and complementary tests to rule out other diseases (Table 3).

Clinical signs and symptoms consistent with PANS.

| Constitutional symptoms | Chills, alopecia (autoimmunity), emaciation (infections or chronic disease) |

|---|---|

| Skin | Scarlatiniform rash, erythema marginatum (rheumatic fever), malar rash (lupus), petechiae (antiphospholipid syndrome), palpable purpura or livedo reticularis (vasculitis), perianal redness (streptococci) |

| Eyes | Mydriasis or slow pupillary response (neurological diseases), Dennie-Morgan folds, bloodshot eye (uveitis or episcleritis) |

| Ear, nose and throat | Nasal congestion or turbinate hypertrophy, sinus tenderness, signs of otitis media, petechiae on palate (streptococci), painless ulcers on palate (lupus) |

| Neck | Adenopathy (autoimmunity), thyromegaly (thyroiditis) |

| Chest | Chest pain, cough, rales or dyspnoea (infection or rheumatological disease), tachycardia or murmur (rheumatic fever) |

| Abdomen | Constipation, diarrhoea, abdominal pain, distended abdomen or blood or mucous in stool (inflammatory bowel disease) |

| Musculoskeletal | Pain, oedema or erythema (arthritis or rheumatic fever), myofascial tenderness or tender points (fibromyalgia) |

| Neurological | Lack of attention, cognitive impairment or memory deficits (autoimmune encephalitis), proximal muscle weakness (dermatomyositis), tics, choreiform movements (rheumatic fever) |

Examinations recommended for patients meeting PANS criteria (adapted from Chang et al.3).

| Recommended: |

| Full blood cell count with white blood cell differential |

| ESR and CRP |

| Comprehensive metabolic panel (liver, kidney and thyroid function) |

| Urinalysis (to assess hydration, rule out inflammation) |

| During episodes: throat culture, ASO (paired tests 4−6 weeks apart with 58% increase have 62% sensitivity) |

| Optional: |

| During episodes: PCR (early, sensitivity >90%) or serology (late) for Mycoplasma, PCR (sensitivity >90%) or serology (75% sensitivity) for influenza, serology for Epstein-Barr (sensitivity >90%) |

| If there are elevated inflammatory markers, fatigue, rashes or joint pain: antinuclear antibodies (ANA) |

| Chorea, petechiae, migraines, thrombocytosis, thrombocytopenia or livedo reticularis: antiphospholipid antibodies including anticardiolipin, dilute Russell's viper venom time, β2 glycoprotein I antibodies |

| If abnormal liver function tests: rule out Wilson's disease by measuring ceruloplasmin and 24-h urine copper |

| Brain MRI in the event of encephalitis, severe headaches, gait disturbances or psychosis to identify vasculitis as the cause |

| EEG if abnormal movements are predominant (abnormal in 16% of PANDAS cases) |

| Polysomnography in the event of insomnia or parasomnias (to look for sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome or abnormal REM sleep) |

| Lumbar puncture if there are MRI or EEG abnormalities. Oligoclonal bands test and antineuronal antibody assay (anti-NMDA) should be performed |

| Swallowing studies when restrictive eating is associated with choking or vomiting |

There are no data demonstrating that any one clinical presentation of streptococcal infection (rhinosinusitis, pharyngitis or bronchitis) makes a patient more susceptible to PANS episodes than other presentations. Streptococcus screening tests are less useful in asymptomatic cases, as was the case in several of the patient's episodes. However, these episodes may be associated with elevated ASO levels, which is why these antibodies were assessed in the reported case.3

By definition, PANS is always a diagnosis of exclusion and a differential diagnosis for PANS primarily includes Sydenham's chorea, autoimmune encephalitis, neuropsychiatric lupus and central nervous system vasculitis.8 In the reported case, Psychiatry and Paediatric Rheumatology as a whole did not document criteria for suspecting these diseases.

With regards to specific tests for PANS, the use of autoantibody biomarkers against dopamine receptors, beta tubulin, lysoganglioside GM1 and calmodulin-dependent kinase (Cunningham Panel) has been proposed. These may be common to Sydenham's chorea but a consistent relationship has not been demonstrated and therefore research continues to be conducted to find other candidate molecules.11,12

Treatment involves a 3-pronged approach: psychotherapy, antimicrobial prophylaxis and immunomodulatory therapy.8,13

Specific adjustments to the patient's daily routine are required during exacerbations as part of psychotherapy. In addition, individual and group support should also be offered to family members. Regarding psychological techniques, the option with the best outcome is cognitive response prevention therapy. To start with, selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors are recommended to modulate symptoms, and antipsychotics may also be added.13

In the case presented above, psychiatric symptoms were partially modulated with fluoxetine, although the associated side effects required that the medication be suspended. The patient also did not tolerate the use of risperidone, which made behaviour management particularly difficult. This drug approach, with fluoxetine and risperidone, has been reported in 29% of children with PANS-PANDAS.5

With regards to specific treatments for groups of neuropsychiatric symptoms, for those cases with tics (present in up to 70% of patients), comprehensive behavioural psychotherapy or habit reversal therapy is recommended. For separation anxiety, gradual exposure therapy with rewards works well. In patients with ADHD, unlike children who do not have PANS, clonidine should be preferred over methylphenidate or atomoxetine. For sleep disturbances, only sleep hygiene measures are recommended. Finally, if the patient has many physical symptoms, physiotherapy should be provided and treatment should be similar to that given for fibromyalgia. These interventions were not instigated during our follow-up window due to the patient's torpid disease progression, despite drug therapy.8,13

With regards to antimicrobial prophylaxis, some data indicate that colonisation by streptococci may trigger episodes and the decision to treat with antibiotics is extrapolated from cases of rheumatic fever. This premise supported our decision to sequentially treat the patient, her mother and her brother with antibiotics, finishing with prophylaxis, although response was only partial, possibly due to exposure to other microbes and the described familial susceptibility.3,6,8

Regarding immunotherapy, the prescription of each immunomodulatory or anti-inflammatory drug should be assessed and adjusted according to the progression of symptoms. Given the tendency of periods of remission and relapse, treatments are cyclical.8 The first-line immunomodulatory therapy is prednisolone, either in short or long cycles. In the second line, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be used as an alternative before resorting to immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis or biological therapy. In the case presented above, these recommendations were followed.7,14 In cases where no response is observed, such as in the case of this patient, immunomodulatory therapy should be suspended and psychotherapy prioritised.8

Regarding prognosis, PANS tends to have fairly high morbidity rates and is highly recurrent in most cases, although some children are cured. However, information from long-term follow-up is very limited. Considering that immunity against streptococcus improves notably at around 12 years of age, a reduction in episodes can be expected during adolescence, especially after puberty. Despite this, its capacity to persist into adulthood is unknown.15

ConclusionsThe case presented above describes the typical clinical course and recommended treatment for PANS-PANDAS, as well as the personal and family burden it may cause. On reviewing this case, it can be seen that any child with OCD or other abrupt and/or recurrent neuropsychiatric symptoms must be studied to determine secondary causes and eventually rule out their association with PANS.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.