Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy after perinatal asphyxia causes neurolinguistic disturbances in children without disabilities. Poor academic performance appears as a long-term result. Language intervention is sought to reduce harmful effects on children. The aim of this study is showing the relationship between clinical conditions of hypoxic-ischemic-encephalopathy (HIE) and language disorders in children without disabilities. This cross-sectional study with a neurolinguistic approach was carried out in patients with perinatal asphyxia during childbirth, at the ZH Sikder Women's Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh. Respondents between 4 and 12 years, 76% underwent cranial computed tomography (CT); 82% underwent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); and 70% underwent electroencephalogram (EEG). Among them were found positive results for neonatal hypoxia ischemic encephalopathy (EHI). These results are related to the following language disorders: reception/perception disorder (64%), sociolinguistic disorders (84%); metalinguistic competence disorder (66%); 86% of children had poor peer relationships and 72% had reading and writing disorders. Concluding, school-age children after perinatal asphyxia who developed Hypoxic-Ischemic Encephalopathy (HIE) had language disorders and poor school performance. There are still challenges to be overcome, as this is the first neurolinguistic approach in Bangladesh. More large-scale studies are needed.

La encefalopatía hipóxico-isquémica neonatal causa alteraciones neurolingüísticas en niños sin discapacidades; el resultado es la aparición de bajo rendimiento académico. Se busca la intervención del lenguaje para reducir los efectos nocivos. Este trabajo muestra la relación entre las condiciones clínicas de la encefalopatía hipóxica-isquémica y los trastornos del lenguaje en niños sin discapacidad. Este estudio transversal con abordaje neurolingüístico se llevó a cabo en pacientes con asfixia perinatal durante el parto, en el ZH Sikder Women's Medical College. Entrevistados entre 4 y 12 años, el 76% se sometió a tomografía computarizada craneal; 82% a imágenes por resonancia magnética y el 70% a electroencefalograma. Entre ellos se encontraron resultados positivos para encefalopatía isquémica por hipoxia neonatal. Los resultados están relacionados con los siguientes trastornos del lenguaje: trastorno de la recepción/percepción (64%), trastornos sociolingüísticos (84%); trastornos de la competencia metalingüística (66%). El 86% de los niños tenía malas relaciones con sus compañeros y el 72% tenía trastornos de lectura y escritura. En conclusión, los niños en edad escolar después de la asfixia perinatal que desarrollaron encefalopatía hipóxico-isquémica tenían trastornos del lenguaje y un bajo rendimiento escolar. Aún quedan desafíos por superar ya que este es el primer enfoque neurolingüístico en Bangladesh. Se requieren más estudios a gran escala.

Interpretation, cognition, spoken language all involve the human linguistic process whose functioning converges to consistency in the interpretive result. This convergence has its foundations in the ‘way’ in which stimuli are processed under a recursive dynamic, building meanings in ascending order of instances.1–3 This dynamic aspect of language understood as a process is of fundamental importance for considering neurolinguistic disorders: if there are obstacles in the transmission of stimuli, there will be interference in the interpretive activity, distorting it.

Broderick et al.4 show, through electrophysiological responses (EEG), that there is a delay in natural speech related to semantic dissimilarity values (incongruent words). The authors claim that neural signatures of semantic dissimilarity depend on intelligibility (completely intelligible stimuli or completely unintelligible stimuli). Crosse et al.5 also assess semantic dissimilarity and intelligibility gradations in experiments involving application of electroencephalogram, EEG, in humans to examine how neural mechanisms help to optimize the cortical representation of auditory speech in a signal-to-noise ratio, showing that natural audiovisual speech processing integrates long temporal windows. Strauß et al.6 note that cognitive mechanisms benefit from context in adverse listening conditions. In an EEG study, the authors found an index of the neural effort of word-context integration. When signal quality is moderately degraded, adverse listening has been found to “narrow”, rather than broaden, expectations about the perceived speech signal, limiting the neural system's perceptual evidence as a sentence unfolds over time. The fact that speech comprehension involves hierarchical representations is demonstrated in the research by Heer et al.7: it starts in the primary auditory areas and moves laterally in the temporal lobe, with both hemispheres equally involved in perception and interpretation of speech. The authors identified that early responses in the auditory hierarchy are more correlated with semantics than with spectral representations, which denotes the importance of using natural speech in neurolinguistic research.

Perinatal asphyxia is seen in this research as an obstacle to the baby's breathing. There is, therefore, an impediment for the baby to start and maintain effective breathing after birth due to the lack of blood flow. In this case, because the blood gas level is not properly changed, there is a decrease in the oxygen level and an increase in carbon dioxide. When there is a dangerous drop in oxygen in the baby's blood and an increase in the level of carbon dioxide, an acid build-up is created. Deep metabolic acidosis with a pH<7.20 can be seen in the umbilical cord arterial blood sample8; it is related to dysfunction in multiple organs such as the heart, lungs, liver, intestine, kidneys, and nervous system in the neonatal period. Brain damage is the most worrying. The clinical manifestation of neurological damage after perinatal asphyxia is known as hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE). If an infant survives neurological damage to the brain, they will manifest intellectual disability, epilepsy, delayed language development, with or without physical disability as a sequelae of hypoxic-ischemic-encephalopathy after perinatal asphyxia.9

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) affects approximately 1.5 in 1000 births and is the most common cause of perinatal brain injury in term infants.10 Annually 4 million neonatal deaths occur due to birth asphyxia; 38% of these deaths occur in children under 5 years of age, according to WHO estimates.8 Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) after perinatal asphyxia (PA) is considered an important long-term consequence for general cognitive linguistic functioning without physical impairment11 because when nervous system development is impaired, language is significantly affected.12 Thus, as long-term consequences, children are affected physically (cerebral palsy), physically and mentally (cerebral palsy with intellectual development disorder), and linguistically (without physical disabilities).13,14

The evolution of the general communication process is closely related to the global development of language. Language is a communication device that involves the use of verbal (speech) and non-verbal (eye contact, gesture, reading and writing) symbols according to the situation and context (pragmatics).11,15,16 Communication analysis includes the observation of phonetics and phonology, cognitive linguistic development, psycholinguistic and social linguistic development.11,16 The absence of language development within the expected chronological age or a delay and difficulty in the language acquisition process may indicate global language development disorders that impair the child's general intelligence, memory, academic performance, and communication.

A parameter to characterize language delay is related to the child's chronological age. A loss in the domain of language acquisition – (receptive, expressive and socialization) within 2 (two) years of age, may mean language development disorder.11,17,18 The difference of at least 12 months between children's linguistic age and chronological age may indicate disturbances in language acquisition and development.19 Children's language skills can be perceived and understood even before their oral manifestations, based on some mechanisms underlying normal language development. The analysis of communication in this period includes the observation of pre-linguistic, cognitive linguistic, psycholinguistic, and social linguistic development.11,12 If there is an early identification of children at high risk for language development disorders,20 it is possible to intervene early through speech therapy, which is essential to prevent or minimize losses.11,21

Poor academic performance due to language disorders among non-disabled children after perinatal asphyxia is a significant burden on the family and the State. Although this poor academic performance is still not given due importance in the Bangladesh Academy, this study brings results that cannot be overlooked: The need to discover language disorders during the period of early childhood development of children without disabilities and with poor academic performance. For this, we suggest a neurolinguistic approach to children who suffered perinatal asphyxia that clinically triggered neonatal encephalopathy.

Materials and methodThis cross-sectional study was conducted during the period February 2019 to February 2021 in the department of Psychiatry at Z.H. Sikder Women's Hospital and School of Medicine, Dhaka, Bangladesh, in accordance with the ethical standards of its responsible committee on human experimentation. 68 children underwent this study, but only 50 of them met the inclusion criteria with a history of a full-term newborn with perinatal asphyxia. The data studied include cranial computed tomography (CT) report; diagnosis of cranial pathology: brain serial axial section was studied from base of the vertex the study reveals hyperdense area in frontal lobe or temporal lobe or both frontal and temporal lobe made by a radiology and imaging specialist; and perinatal asphyxia with neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) diagnosed by the pediatrician, after delivery and during hospitalization.

Details of the mother's medical history, prenatal illnesses, type of delivery, duration of labor, and medications administered were obtained along with information about the children's history of delayed language development and school refusal. Included were magnetic resonance imaging (MRI of the brain); diagnosis of brain MRI pathology: multi planner and multi sequences without contrast which included sagittal T1, Axial FLAIR, axial diffusion and ADC, GRE and axial T2, coronal. T2 sequences had a abnormalities, T1 had hypo intensities and T2, FLAIR hyperintensities in frontal lobe or temporal lobe or both in frontal and temporal lobe with anatomical location made by a radiology and imaging specialist. Electroencephalogram (EEG) had abnormal electrical activity found in anatomically located in the signal of the electrodes in the frontal lobe the electrodes (right side: F4-Superior frontal, FP2-Prefrontal, F8-Inferior frontal; left side: F3-Superior frontal, FP1-Prefrontal, F7-Inferior frontal; FZ-Mid frontal). Or found in the temporal lobe: right side: T4-Mid temporal, T6-Post temporal; left side: T3-Mid temporal, T5-Post temporal) or abnormalities were found in the frontal and temporal lobes, in brain waves or electrical activity recorded in brain reports, diagnosed by a neurophysiologist after school refusal.

Children aged between 4 and 12 years were consecutively admitted to the study. To purposefully assess the frequency and characteristics of language disorder, participants were interviewed by an experienced clinical linguist and a clinical diagnosis psychiatrist attentive to DSM-5. Before starting the research, the main author obtained the consent of the patients’ parents and guardians. This researcher informed them that all data obtained will be kept confidential and that they could withdraw from the research at any time, whenever they wished. Informed consent and socio-demographic data were obtained, and each patient was individually assessed. The pre-elaborated questionnaire was filled out with the information collected. All clinical assessments were performed by a psychiatrist, clinical linguist/language specialist, specialist in Radiology and Imaging and, also a neurologist. The research instruments were a pre-elaborated structured questionnaire, developed for caregivers; the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 (DSM-5); Brain Computed Tomography, CT, Brain MRI and EEG report. Some limitations for the study were observed, for example, the cases in which the patient, caregiver (mainly the mother), was undergoing treatment far from the city of Dhaka, having faced many challenges in a pandemic situation. Another difficulty is the low education level of the caregiver, which limits the data collection procedure. The lack of financial resources also adds to the limitations, as many caregivers had to travel to Dhaka city and the monitoring, which should be daily, was hampered by the lack of funding for their trips.

Inclusion criteria- •

Those with clinical diagnosis of Intellectual disability with language disorder according to Diagnostic and Statistical Mannual-5 (DSM-5). Clinical diagnosis of epilepsy with language disorder according to the Diagnostic Manual of Epilepsy (ILAE).

- •

Those who had a history of perinatal asphyxia, term baby with hospital admission and document of diagnosis of hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy by pediatrician after delivery.

- •

Age range 4–12 years (up to 18 years of age are considered children according to the World Health Organization).

- •

Children with vision and hearing abilities within normal limits as documented by either formal audiovisual evaluation or screening.

- •

Those who are capable of being submitted to CT-Scan, MRI and EEG report exams.

- •

Children with vision and hearing impairment.

- •

Children with physical disability related to language disorder.

- •

Children with other language developmental delay (e.g. Autism Spectrum disorder, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder etc.).

- •

Children with language disorder due to tumor or other event in language processing area (Broca's area, Wernicke's area, and their associated fibers).

- •

Children with global developmental delay.

- •

Those who are not capable of being submitted to CT-Scan, MRI, and EEG report.

All children who had a history of perinatal asphyxia and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy after delivery, and all who had a clinical diagnosis of language disorders during the developmental period between 4 and 12 years of age, were selected. Then, they underwent brain computed tomography, brain MRI and EEG.

Some children had a positive finding on MRI: a hyperintense area was found in the frontal lobe (Broca's area or area 44.45), which is related to expressive language disorders, as it is an area responsible for the expression of language. In the temporal lobe, Wernicke's area is responsible for the perception, interpretation and understanding of visual and auditory linguistic information. Those who had a positive finding on magnetic resonance imaging of a hyperintense area in the temporal lobe, presented receptive/perceptive language disorder in visual and auditory linguistic information.

Positive MRI results on some children are related to a hyperintense area found in the frontal lobe and temporal lobe, which is Broca's area and Wernicke's area. These children have expressive language disorders and receptive/perceptive language disorders.

Some individuals had a positive finding on brain computed tomography, indicating the existence of a hypodense area in the frontal lobe, which is Broca's area or area 44.45, related to expressive language disorders because it is an area linked to the expression of language. In the temporal lobe, Wernicke's area is responsible for decoding visual and auditory linguistic information, which is the perception, interpretation and understanding of visual and auditory linguistic information. Those who had a positive finding on computed tomography of the brain for the hypodense area found in the temporal lobe, presented receptive/perceptive language disorders, as it is an area responsible for the perception, interpretation and understanding of visual and auditory linguistic information. These positive results on brain computed tomography for hypodense areas in both the frontal and temporal lobes (Broca and Wernicke areas) are related to expressive language disorders and receptive/perceptive language disorders of the examined subjects.

Abnormal electrical activity on the EEG of some children was found in the frontal lobe (Broca's area or area 44.45) who had expressive language disorders. In the temporal lobe, Wernicke's area is responsible for decoding visual and auditory linguistic information (perception, interpretation and understanding of visual and auditory linguistic information). Those who had found abnormal electrical activity in the EEG (temporal lobe), present receptive/perceptive language disorders (because it is an area responsible for the perception, interpretation and understanding of visual and auditory linguistic information). Some children have been observed to have abnormal electrical activity in both the frontal and temporal lobes (Broca's and Wernicke's areas), presenting expressive language disorders and receptive/perceptive language disorders.

The following instruments were used for this study: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-5 (DSM-5), the Diagnostic Manual of Epilepsy (ILAE), the pre-prepared questionnaire for the caregiver, brain computed tomography, brain magnetic resonance and EEG.

Descriptive statistics were used for demographic data and the data were presented as tables.

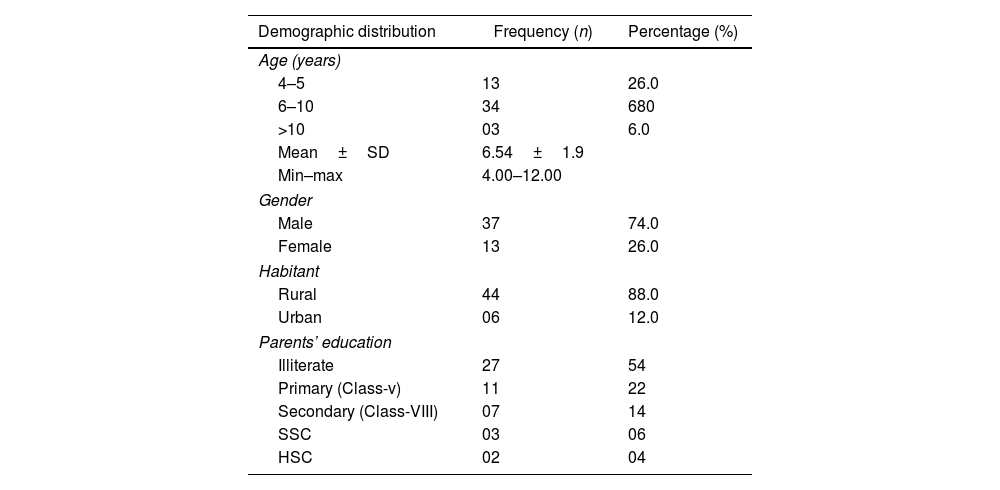

ResultsThe study duration was two years. Participation rate was 50 children. The average age of respondents was 6.54±1.9 years, ranging from 4 to 12 years. Among 50 children enrolled, the majority (68%) were 6 to 10 years old, 3% were>10 years old, and the remainder (26%) were 4–5 years old. 74% were male and 26% female. Most children (88%) lived in rural areas and their parents’ education was illiterate. Most parents (54%) were illiterate (they did not go to school); 22% were in primary school (meaning that in the Bangladeshi education system ranked in grades 1–10, they had reading ability corresponding to grade 5); 14% reached the eighth grade and discontinued their studies; 0.6% of those who completed high school managed to obtain the SSC (High School Certificate); 0.4% completed high school HSC (Obtained Higher Secondary School Certificate) (see below Table 1).

Demographic distribution of the patients (N=50).

| Demographic distribution | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| 4–5 | 13 | 26.0 |

| 6–10 | 34 | 680 |

| >10 | 03 | 6.0 |

| Mean±SD | 6.54±1.9 | |

| Min–max | 4.00–12.00 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 37 | 74.0 |

| Female | 13 | 26.0 |

| Habitant | ||

| Rural | 44 | 88.0 |

| Urban | 06 | 12.0 |

| Parents’ education | ||

| Illiterate | 27 | 54 |

| Primary (Class-v) | 11 | 22 |

| Secondary (Class-VIII) | 07 | 14 |

| SSC | 03 | 06 |

| HSC | 02 | 04 |

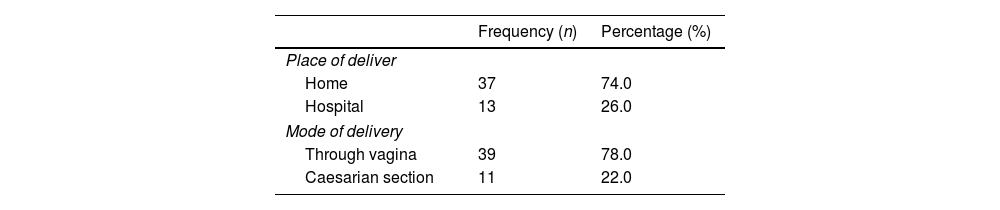

Place of delivery: 74% at home and 26% hospital. Mode of delivery: 78% via the vagina and 22% Cesarean at the hospital after monitoring at home (see Table 2).

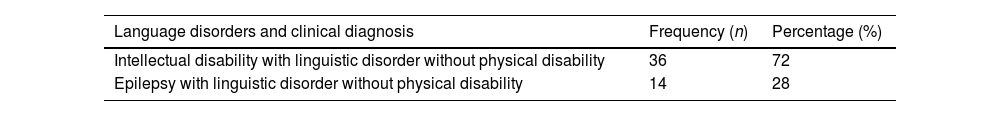

Clinically, 72% of children were diagnosed with intellectual development disorder and language disorder without physical disability; 28% were diagnosed with epilepsy accompanied by language impairment and no physical disability (see Table 3).

Clinical diagnosis was present in school-age children after perinatal asphyxia (N=50).

| Language disorders and clinical diagnosis | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Intellectual disability with linguistic disorder without physical disability | 36 | 72 |

| Epilepsy with linguistic disorder without physical disability | 14 | 28 |

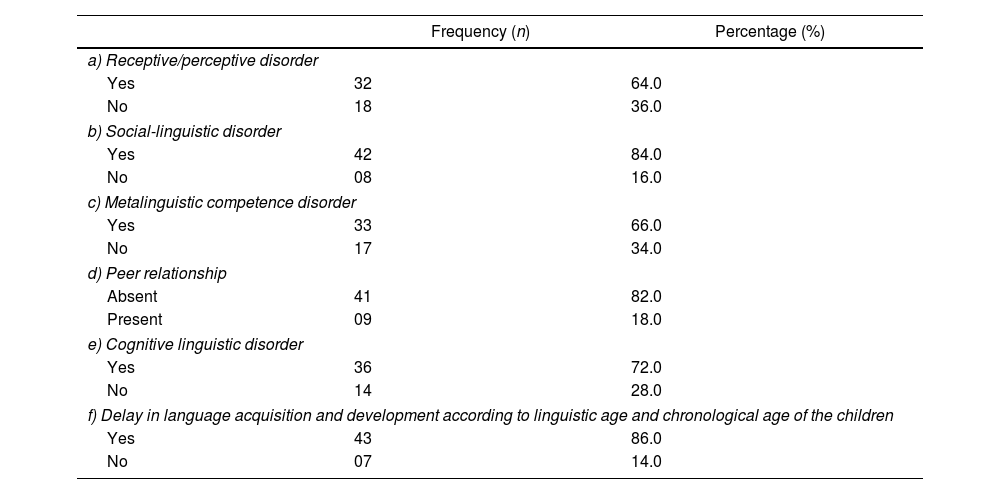

Linguistic disorders were present among school-age children (64%) after perinatal asphyxia, evidencing inability to understand the complex speech of other people according to the social context (Disorder of reception/perception). Most children had sociolinguistic disorders (84%) and metalinguistic competence disorders (66%). As a result of these disorders, 86% of the children had poor relationships with peers, and 72% had reading and writing disorders (Linguistic-Cognitive Disorder) (see Table 4).

Language disorders were present among school-age children after perinatal asphyxia (N=50).

| Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| a) Receptive/perceptive disorder | ||

| Yes | 32 | 64.0 |

| No | 18 | 36.0 |

| b) Social-linguistic disorder | ||

| Yes | 42 | 84.0 |

| No | 08 | 16.0 |

| c) Metalinguistic competence disorder | ||

| Yes | 33 | 66.0 |

| No | 17 | 34.0 |

| d) Peer relationship | ||

| Absent | 41 | 82.0 |

| Present | 09 | 18.0 |

| e) Cognitive linguistic disorder | ||

| Yes | 36 | 72.0 |

| No | 14 | 28.0 |

| f) Delay in language acquisition and development according to linguistic age and chronological age of the children | ||

| Yes | 43 | 86.0 |

| No | 07 | 14.0 |

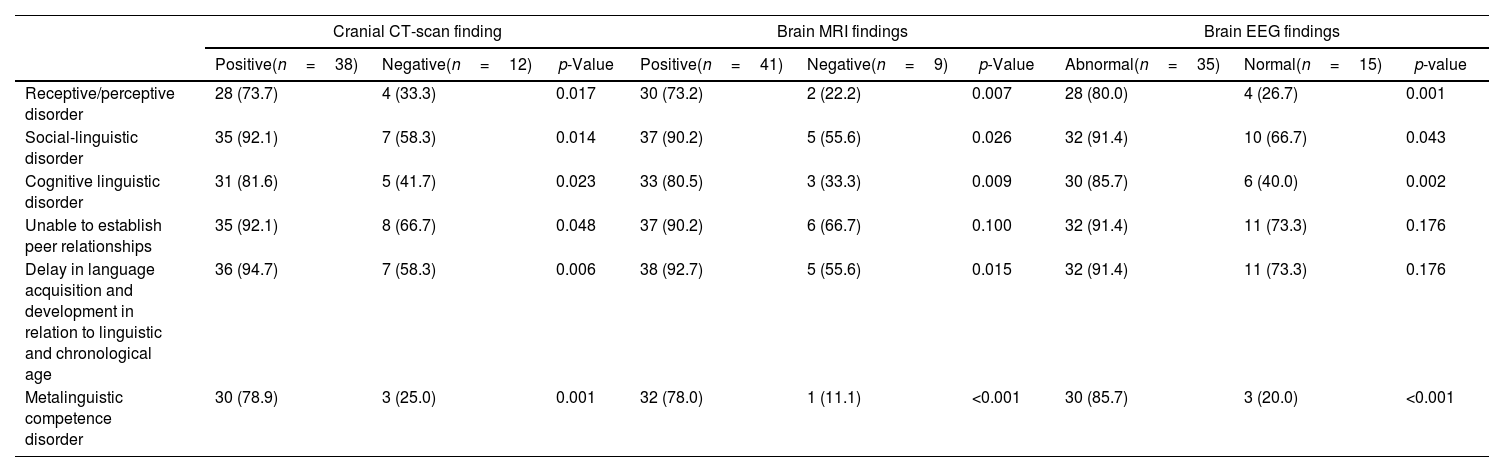

All children had a clinical diagnosis of language disorder among them, 38 (76.0%) of the children had a cranial CT scan report with an anatomical location of hypodense area found in the frontal lobe (Brocas’ area) or temporal lobe (Wernicke's area) or both in the frontal and temporal lobe. Among the positive findings of cranial CT findings, 73.7% of children had receptive/perceptive disorders, 92.1% had social-linguistic language disorders, 81.6% had cognitive linguistic disorder, 92.1% of the children were unable to establish peer relationship, 94.7% had delay in language acquisition and development according to children's linguistic and chronological age and 78.9% had metalinguistic competence disorder (Table 5).

Association of language disorder with cranial CT-Scan, brain MRI and brain EEG findings.

| Cranial CT-scan finding | Brain MRI findings | Brain EEG findings | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive(n=38) | Negative(n=12) | p-Value | Positive(n=41) | Negative(n=9) | p-Value | Abnormal(n=35) | Normal(n=15) | p-value | |

| Receptive/perceptive disorder | 28 (73.7) | 4 (33.3) | 0.017 | 30 (73.2) | 2 (22.2) | 0.007 | 28 (80.0) | 4 (26.7) | 0.001 |

| Social-linguistic disorder | 35 (92.1) | 7 (58.3) | 0.014 | 37 (90.2) | 5 (55.6) | 0.026 | 32 (91.4) | 10 (66.7) | 0.043 |

| Cognitive linguistic disorder | 31 (81.6) | 5 (41.7) | 0.023 | 33 (80.5) | 3 (33.3) | 0.009 | 30 (85.7) | 6 (40.0) | 0.002 |

| Unable to establish peer relationships | 35 (92.1) | 8 (66.7) | 0.048 | 37 (90.2) | 6 (66.7) | 0.100 | 32 (91.4) | 11 (73.3) | 0.176 |

| Delay in language acquisition and development in relation to linguistic and chronological age | 36 (94.7) | 7 (58.3) | 0.006 | 38 (92.7) | 5 (55.6) | 0.015 | 32 (91.4) | 11 (73.3) | 0.176 |

| Metalinguistic competence disorder | 30 (78.9) | 3 (25.0) | 0.001 | 32 (78.0) | 1 (11.1) | <0.001 | 30 (85.7) | 3 (20.0) | <0.001 |

Chi-square/Fisher's exact test was done.

Among the study children, 41(82.0%) had a positive MRI report. The radiological finding of anatomical location was the hyperintense area found in the frontal lobe (Broca's area) or in the temporal lobe (Wernicke's area) or both in the frontal and temporal lobes. Of these, 73.2% had receptive language disorder, 90.2% had social-linguistic disorder, 80.5% had cognitive linguistic disorder, 90.2% were unable to establish peer relationship, 92.7% had delay in language acquisition and development according to children's linguistic and chronological age and 78.0% had metalinguistic competence disorder (Table 5).

Among the study children using brain EEG findings, 35 (70%) had abnormal electrical activity in the frontal lobe (Broca's area) or in the temporal lobe (Wernicke's area) or both in the frontal and temporal lobes. Among them 80.0% had receptive language disorders, 91.4% had social-linguistic disorder, 85.7% had cognitive linguistic disorder, 91.4% were unable to establish peer relationship, 91.4% had delay in language acquisition and development in relation to linguistic and chronological age, and 85.7% had metalinguistic competence disorder (Table 5).

So, the association of language disorder to brain CT-Scan, MRI and EEG findings shows a significant p-value: p<0.05.

DiscussionAs explained in the Introduction, perinatal asphyxia is the most prevalent neurological disorder in the neonatal period. The deleterious effects of hypoxia and ischemia affect the central nervous system and impair general language development. To demonstrate these harmful effects, we show, in Table 1, that the individuals surveyed were children aged between 6 and 10 years, a period in which reading, and writing are developed.

In Table 2 we show the place of birth at home and in the hospital and what was the mode of delivery and whether the baby was monitored at home. It was then shown, in Table 3, that most children, without physical disabilities, presented delay in language acquisition and development in relation to their linguistic and chronological age. These data are comparable to studies by Marlow et al., 14 in which the authors found most of the children 42% of the severe encephalopathy group without motor disability, IQ levels were lowest and some children had memory and executive perceptive disorder.

Table 4, in turn, shows that 64% of the analyzed individuals could not understand the complex speech of other people according to the social context and that this was related to the hyperintense area found in the temporal region. The Socio-Linguistic Disorder of 84% of the individuals was related to the hyperintense area found in both the frontal and temporal regions (Table 4). The hyperintense area in the temporal region was associated with Metalinguistic Competence Disorder in 66% of the individuals (Table 4). Poor peer relationships in 86% of children were associated with the hyperintense area found in the frontal and temporal regions (Table 4). The hyperintense area found in 72% of the children, both in the frontal and temporal regions, was associated with reading and writing disorders (Table 4). These findings recorded in Table 4 are in line with the findings of Martinez et al.,22 in which the authors observed a relationship of 84.63% individuals with language difficulties and 86.50% with sociolinguistic disorder with the finding of a hyperintense area found in the frontal and temporal area.

Table 5 shows a comparison of diagnoses of disorders available for investigation by placing findings side by side using cranial CT-Scan, brain MRI and brain EEG findings. 76% of the children who had a cranial computed tomography (cranial CT) report had a positive finding for neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) after delivery during hospitalization (Table 5). Most of them, 82%, had positive magnetic resonance imaging (brain MRI) and 70% had EEG (electroencephalogram) changes after school refusal (Table 5). Chin et al.13 indicate in their magnetic resonance studies (Brain MRI) that there is a hyperintense area in the frontal region that affects expressive language disorder in 8.1% of the patients evaluated by them and that the existence of a hyperintense area in the temporal region that was related to receptive language disorder in 18.5% of their patients. They13 also found 27% of individuals with an IQ (intellectual disability) below 70%. This finding by the authors13 – regarding the language development profile of children after hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy affecting the development of receptive and expressive language and affecting children's academic performance – is comparable to our study with positive results from magnetic resonance imaging. shown in Table 5 (that is, 73.2% had receptive language disorder, 90.2% had social-linguistic, 80.5% had cognitive-linguistic disorder, 90.2% were unable to establish relationships with peers, 92.7% had delay in language acquisition and development according to the linguistic and chronological age of the child and 78.0% had metalinguistic competence disorder).

Abnormal EEG findings shown in Table 5 indicate that 80.0% of children had receptive language disorders, 91.4% had sociolinguistic disorder, 85.7% had cognitive linguistic disorder, 91.4% were unable to establish a relationship with peers, 91.4% had delay in language acquisition and development in relation to linguistic and chronological age and 85.7% had metalinguistic competence disorder. This is an expressive association of language alteration with brain EEG findings with p<0.05 (Table 5). These data are comparable to studies by Broderick et al.5 in which the authors found that the EEG reflects the semantic processing of continuous natural speech intelligibility, and that when the electrical activity is abnormal in the EEG exams, the authors5 associated to neurological disorders in the cerebral temporal area with p-value<0.02.

Gonzalez and Miller23 found in their study 25% of individuals with inability to memorize reading and writing (cognitive-linguistic deficit) related to the hyperintense, and hypodense area found in both the frontal and temporal regions. In another study24 comparable to our study (Table 5), it was observed that in 16% of respondents who were of school age, 35% had a lack of reading ability, 18% had a lack of spelling ability, and 20% had difficulty in arithmetic due to pathological changes related to finding a hyperintense area and a hypodense area found in the frontal and temporal regions of the brain.

This study, by associating findings on language disorders with diagnoses obtained with the use of cranial CT-Scan, brain MRI and brain EEG becomes significant for studies on human language and cognition. The comparative table of those findings (Table 5) gives an overview of the linguistic process whose functioning converges to interpretation and cognition.1–3 Stimuli are processed under a recursive dynamic1,2 which, when faced with abnormalities, negatively affects the neurolinguistic process as a whole.1 This dynamic aspect of language cannot be ignored by academics and medical professionals.

ConclusionThis descriptive observational study was carried out from the concept of language as a dynamic process and not as a substance. Poor school performance in children between 4 and 12 years of age has been described due to language disorders after perinatal asphyxia, a phenomenon that most often goes unnoticed. Our study, supported by similar findings from other researchers, innovates by correlating these language disorders with findings in cranial computed tomography (CT of the brain), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI of the brain), and electroencephalogram (EEG) that had positive results for neonatal hypoxia ischemic encephalopathy (HIE). The significant findings in the correlation coefficients that were achieved in this research make this work an important contribution to research in the areas of cognition, language, education, pedagogy, neuroscientific studies, among others. The demonstration through relationships between children's neurolinguistic behavior and the abnormalities pointed out by CT-Scam, MRI and EEG exams reinforces the view that the linguistic process works in order to converge toward interpretation and cognition. Under a recursive dynamic1,2 this process, in the face of abnormalities, has its functioning impaired, reaching interpretation and cognition. This dynamic aspect of language1–3 needs to be further explored by academics and medical professionals to take advantage of brain plasticity.25 In this way, it is possible to search for adequate knowledge of the principles of human neuroplasticity that lead children to better interpret, relate socially and improve classroom practices.25 This research also shows that the follow-up of these children, through early diagnosis and intervention through assessment and speech therapy, can reduce the deleterious effects of cognitive damage suffered by the individual due to lack of oxygen. This intervention has the role of increasing the brain's capacity for self-regeneration, stimulating it to develop according to the social context to bring a better quality of life to patients and reduce family, social and State burden.

FundingSelf-funded.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.