There is a lack of studies on the natural history of the initial stages of schizophrenia in Colombia. This study aims to assess functionality in the first five years after the diagnosis of schizophrenia.

MethodsNaturalistic longitudinal study of 50 patients with early schizophrenia evaluated between 2011 and 2014. Data about demographic background, symptoms, introspection, treatment and adverse reactions were collected in all patients every 3 months for at least 3-5 years. Functionality was measured with the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) and Personal and Social Performance (PSP) scales.

ResultsPatients were followed up for a mean of 174±62.5 weeks and showed moderate difficulties in overall functioning. This functioning was modified by polypharmacy, degree of introspection, changes in antipsychotic regimens, and the number of episodes, relapses and hospitalisations.

ConclusionsThe results suggest that functional outcomes seem to be related to the use of polypharmacy, degree of insight, changes in antipsychotic regimens, and number of episodes, relapses and hospitalisations during the first years of schizophrenia.

Existe una falta de estudios en la historia natural de los estadios iniciales de la esquizofrenia en Colombia. Este estudio apunta a evaluar la funcionalidad en los primeros cinco años después del diagnóstico de esquizofrenia.

MétodoEstudio longitudinal naturalístico de 50 pacientes con esquizofrenia temprana evaluados entre los años 2011 y 2014. Loa datos demográficos, síntomas, introspección, tratamiento, y reacciones adversas fueron recolectados en todos los pacientes cada 3 meses por lo menos 3 a 5 años. La funcionalidad se midió mediante la escala global de funcionamiento (GAF), y la escala de funcionamiento personal y social (PSP).

ResultadosLos pacientes fueron seguidos por una media de 174 semanas (SD: 62.5) y mostraron dificultades moderadas en su funcionamiento global. Este funcionamiento fue modificado por la presencia de polifarmacia, grado de introspección, cambios en los esquemas antipsicóticos, y el número de episodios, recaídas, y hospitalizaciones.

ConclusionesLos resultados sugieren que los desenlaces en funcionalidad parecen estar relacionados con uso de polifarmacia, grado de introspección, cambios en esquemas antipsicóticos, y numero de episodios, recaídas, y hospitalizaciones durante los primeros años de esquizofrenia.

The first years after the diagnosis of schizophrenia are crucial to determining some parameters involved in the long-term clinical and functional outcomes.1 It is a period that involves risks such as relapses 2and suicide.3 As the first episode of psychosis (FEP) usually emerges around the twenties, this period also concurs with individual development milestones such as identity establishment, peer networks, vocational training, and intimate relationships.

This focus in early stages is based on the “critical period hypothesis”, which proposes that the period around a FEP, including any period of initially untreated psychosis, is a ‘critical period’ during which deterioration progresses rapidly.4 Prior evidence suggests that progression of the disease, functional disability, and psychosocial deterioration might occur predominantly in the first three to five years, after which schizophrenia reaches a clinical plateau.5 Even some of the grey matter abnormalities in schizophrenia worsen shortly after the onset of psychosis, although abnormal development of the brain usually begins many years before the first episode.6

This approach has led to the implementation of interdisciplinary early intervention programs around the world that have shown superiority versus usual treatment strategies.7 However, some argue that these services waste scarce resources in an “arbitrary critical period of a few years”,8 given that schizophrenia is not necessarily a neuroprogressive disease and poor functional outcomes that some patients exhibit may reflect other conditions (such as limited healthcare access, poor adherence to treatment, and social and financial impoverishment).9

However, functional recovery during the first months after a FEP significantly predicts longer-term full recovery, even more than early symptomatic remission itself.10 This finding aligns with the top 5 life and treatment goals of young people hospitalized for a FEP: employment, education, housing, relationships and health.11 In order to achieve these targets, a community-based treatment program is mandatory, involving psychological, pharmacological, social, and occupational interventions. Despite current guidelines recommend an assertive community treatment,12,13 complete access to an integrated community-based team service is still scarce in our country.14 Besides, in Colombia there are no reports on the natural history of the disease the first years after its diagnosis, so we cannot rule out if early stages determinants can also be related to functional outcomes years later. Hence, we decided to carry out a descriptive analysis of the functionality in the first five years after the diagnosis of schizophrenia.

MethodsFifty patients with early schizophrenia, defined as the first 5 years since diagnosis, were included in a naturalistic cohort. Patients aged between 18 and 35 years in pharmacological treatment for schizophrenia, who signed the informed consent and had at least one person who could provide information about the evolution of the symptoms, were assessed between July 2011 and May 2017. Patients were excluded if they had another diagnosis in DSM-IV Axis I (except for substance abuse/dependence) or a severe personality disorder, if they were living in a nursing center or were participating in clinical studies with research products (even 30 days before first evaluation), or if they could not comply with the registration procedures according to the investigator's opinion.

The diagnosis of schizophrenia was confirmed with the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). Patients were assessed by a trained psychiatrist (JFC, JJO, C-P, A-V) between July 2011 and May 2017 in the Centro de Investigaciones del Sistema Nervioso (Grupo CISNE), Bogota. All patients were followed up every 3 months during at least 3 years and up to 5 years, with periodic evaluations every 3 months. The initial idea was to follow them up for a period of 5 years, but it was shortened to 3 years given the low rate of admission to protocol. Seven patients dropped out the study (6 after 2 years of follow up, and 1 after 1 year of follow up): 2 of them moved out of the city, and 5 decided not to go back to the medical center. Since this was a naturalistic observational longitudinal study, there were no guidelines for the treatment administered, and no changes were made in therapeutic schemes.

At baseline, a complete personal and family history was performed. Demographic data were obtained, as well as information about the disease (prodromal symptoms, duration of illness, functional baseline status, clinical severity, pharmacological history) and substance use. In every visit, physical health indicators (blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, weight, height, and body mass index) and information about treatment and adverse reactions data were collected. Blood and urine samples were obtained in baseline and selected follow-up visits in order to perform blood counts, blood chemistry tests (lipids profile, glycemia, liver and kidney function tests), endocrine function (thyroid hormones and prolactin levels), urinalysis and urine drug panel.

Functional outcomes were assessed with: a) Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) Scale, a widely used instrument to evaluate the general functioning of patients with psychiatric disorders along a hypothetical illness-health continuum ranging from 1 (severely impaired) to 100 (superior functioning) based on precise instructions (this instrument has a good reliability, but its concurrent and predictive validity tend to be more problematic),15 and b) Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP), a reliable, valid and sensitive instrument for measuring functioning in outpatients with schizophrenia developed by Morosini et al.16 and validated in Spain17 to assess the degree of difficulty a subject has exhibited the last month in 4 domains that are usually impaired in schizophrenia: socially useful activities, personal and social relationships, self-care, and aggressive or disturbing behavior. In every visit severity of symptoms was measured with the Clinical Global Impression Severity scale (CGI-S), a valid, quick, simple and reliable clinical outcome measure suitable for routine use in psychiatry.18 Insight was evaluated with the Scale for Assessment of Insight, Expanded Version (SAI-E), whose validity and reliability were previously confirmed in Colombian patients with both affective and psychotic disorders.19

The investigation ethics committee approved the study before the first registration was made. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

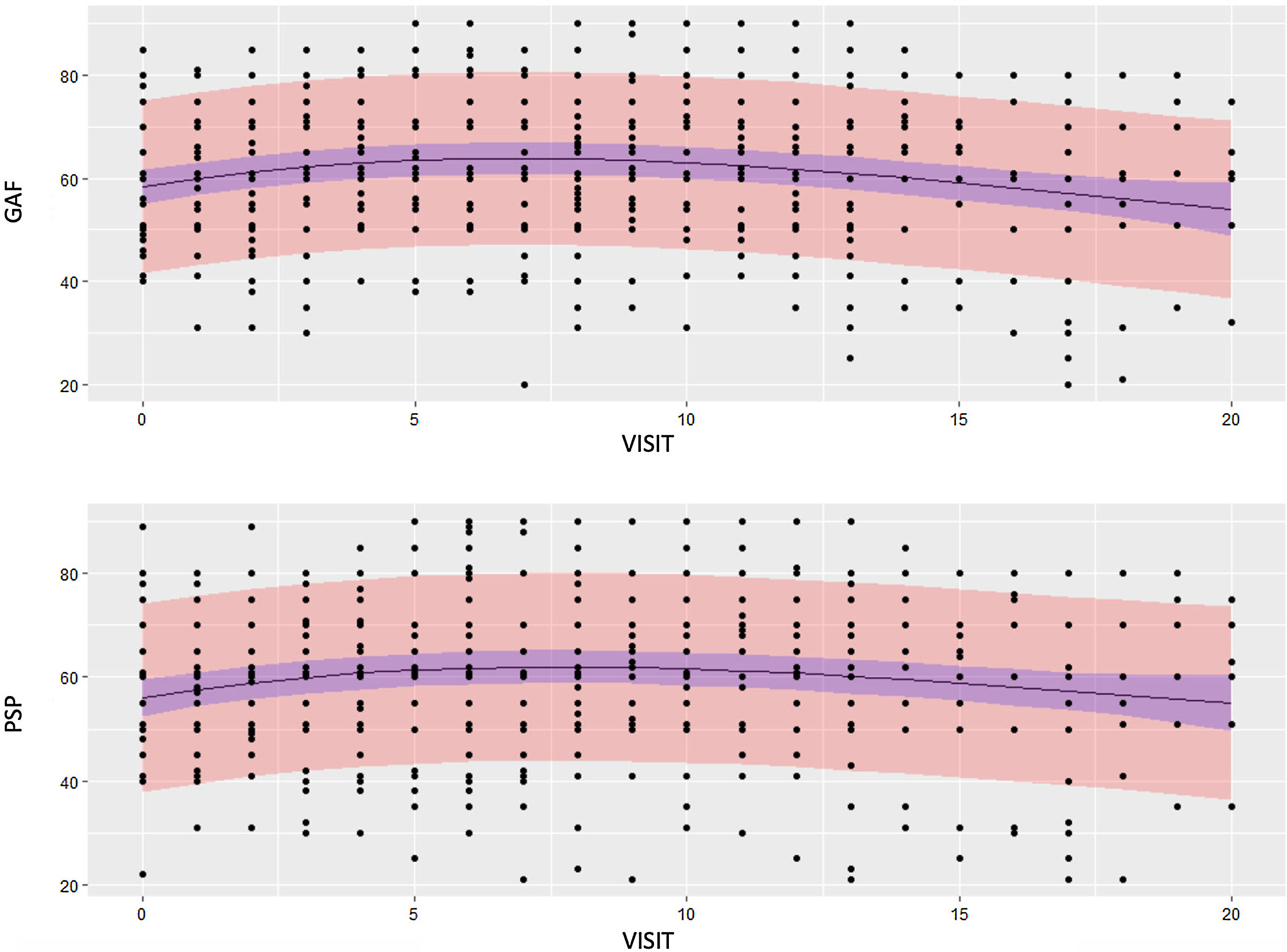

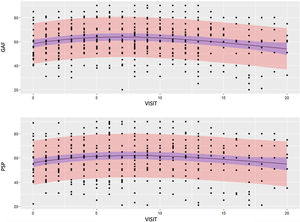

The data set was collected in EpiINFO version 3.5.3. and then analyzed in software R version 3.4.2. Categorical variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies and percentages, whereas continuous variables were computed with typical dispersion and central tendency measures. In order to establish if the functionality measured by the GAF and PSP scales had some tendency over time, we adjusted a mixed linear model with polynomial components of order 3 to explain the trend of the scales over time. The marginal correlation between both scales was high (0.9), so results were similar for both. Linear mixed models were constructed to determine whether the tendency over time observed for functionality could be affected by other variables.

ResultsPatients were followed-up for a mean of 174±62.5 weeks. Most of them were single and unemployed men with secondary school grades. Details of demographic characteristics are described in table 1.

Although all of the patients were using antipsychotics at the beginning of the study (mainly oral second-generation antipsychotics [SGA]), only 4 of them had non-pharmacological therapies. Two out of 3 patients needed another medication in addition to the core antipsychotic (Table 1), mainly benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and other antipsychotics. The rate of lifetime substance use observed was 36%. The median duration of the prodrome was 71.7 [interquartile range, 134.9] weeks, and the median duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) was 62.2 [102.75] weeks (Table 1).

Baseline clinic and demographic characteristics.

| Male gender | 44 (88) |

| Job status | |

| Unemployed | 34 (68) |

| Student | 10 (20) |

| Independent (arts, sports) | 3 (6) |

| Employed | 3 (6) |

| Age (years) | 23 [4.75] |

| Educational level (years) | 11 [2] |

| Duration of prodrome (weeks) | 71.7 [134.9] |

| Duration of untreated psychosis (weeks) | 62.2 [102.75] |

| Duration of illness (weeks since diagnosis) | 71.6 [151.3] |

| Total number of episodes | 3 [3.75] |

| Total number of hospitalizations | 3 [3.75] |

| Baseline insight (SAI score) | 13.18 [8.75] |

| Baseline GAF Score | 55 [15] |

| Baseline PSP Score | 55 [14.3] |

| Initial antipsychotic | |

| Second-generation | 48 (96) |

| First-generation | 2 (4) |

| Route of administration | |

| Oral | 42 (84) |

| Intramuscular | 8 (16) |

| Use of concomitant medication | |

| No | 15 (31.9) |

| Benzodiacepines | 30 (60) |

| Antipsychotics | 14 (28) |

| Antidepressants | 14 (28) |

| Mood stabilizers | 14 (28) |

| Anticholinergics | 8 (16) |

| Antihystamines | 4 (8) |

| Levothyroxine | 3 (6) |

| Other drugs | 8 (16) |

| Non-pharmacological therapies | 4 (8) |

| Substances misuse | 18 (36) |

GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; PSP: Personal and Social Performance Scale; SAI: Scale for Assessment of Insight.

Data are expressed as n (%) or median [interquartile range]

Table 2 shows the results of the mixed linear model for GAF and PSP scales over time. In figure 1, a barely detectable Order 2 polynomial trendline can be seen, revealing that the scores of both scales slightly increased after the first visits, reaching a maximum around the seventh visit (84th week) and then decreasing to levels slightly lower than baseline scores.

Results of mixed linear models for functionality scales.

| GAF | PSP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | t-value | P-value | Value | t-value | P-value | |

| (Intercept) | 58.36282 | 34.56749 | <.00001 | 56.05111 | 31.73638 | – |

| Visita | 1.73765 | 3.73035 | .0002 | 1.7129 | 3.40839 | .0007 |

| I(visita^2) | –0.15632 | –2.53613 | .0115 | –0.14267 | –2.14542 | .0323 |

| I(visita^3) | 0.00293 | 1.32188 | .1867 | 0.00273 | 1.13877 | .2553 |

GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; PSP: Personal and Social Performance Scale.

To evaluate whether the trend in time observed for functionality could be affected by other variables, several linear mixed models were constructed. The variables with a significant effect on the trends of both GAF and PSP scores were use of concomitant medications, modifications in the antipsychotic scheme, number of episodes before baseline visit, degree of insight, number of relapses, and number of hospitalizations. None of these linear mixed models was able to find any correlation between substance use or DUP and changes in functionality during follow-up.

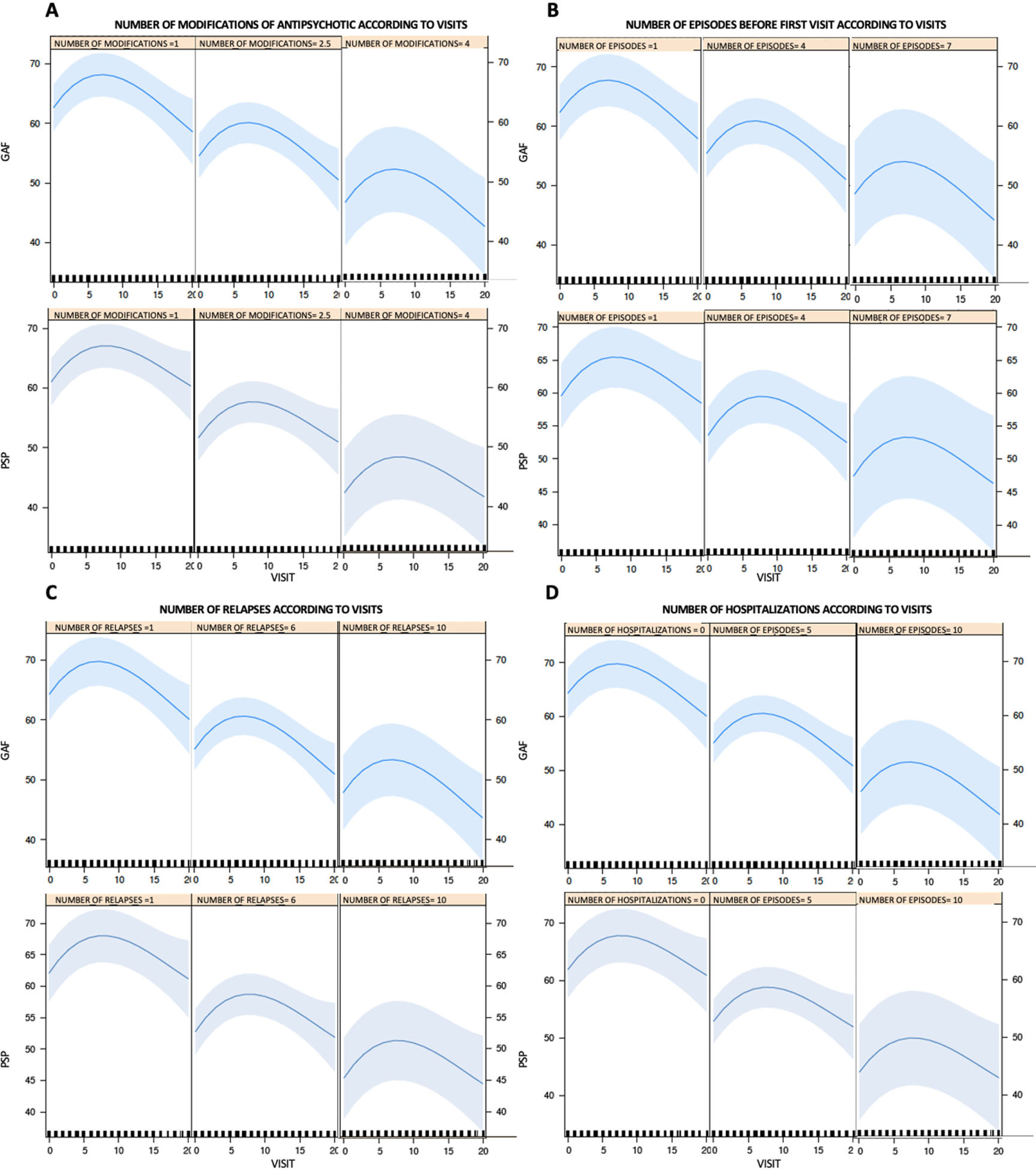

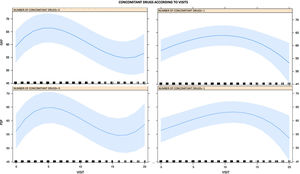

As it is shown in figure 2, the greater the number of episodes, hospitalizations, relapses and changes in the antipsychotic scheme, the lower the level of functionality (measured with any of the scales) both at the beginning and throughout the follow-up. However, a higher number of episodes before the first visit, relapses, hospitalizations and modifications in antipsychotic schemes during the first 5 years after diagnosis of schizophrenia did not affect trends of functionality over time: the GAF and PSP scores slightly improved during the first weeks but then progressively decreased.

GAF and PSP scores trends during follow-up versus: number of modifications in antipsychotic schemes (A), number of episodes before first visit (B), number of relapses (C), and number of hospitalizations (D). GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; PSP: Personal and Social Performance Scale.

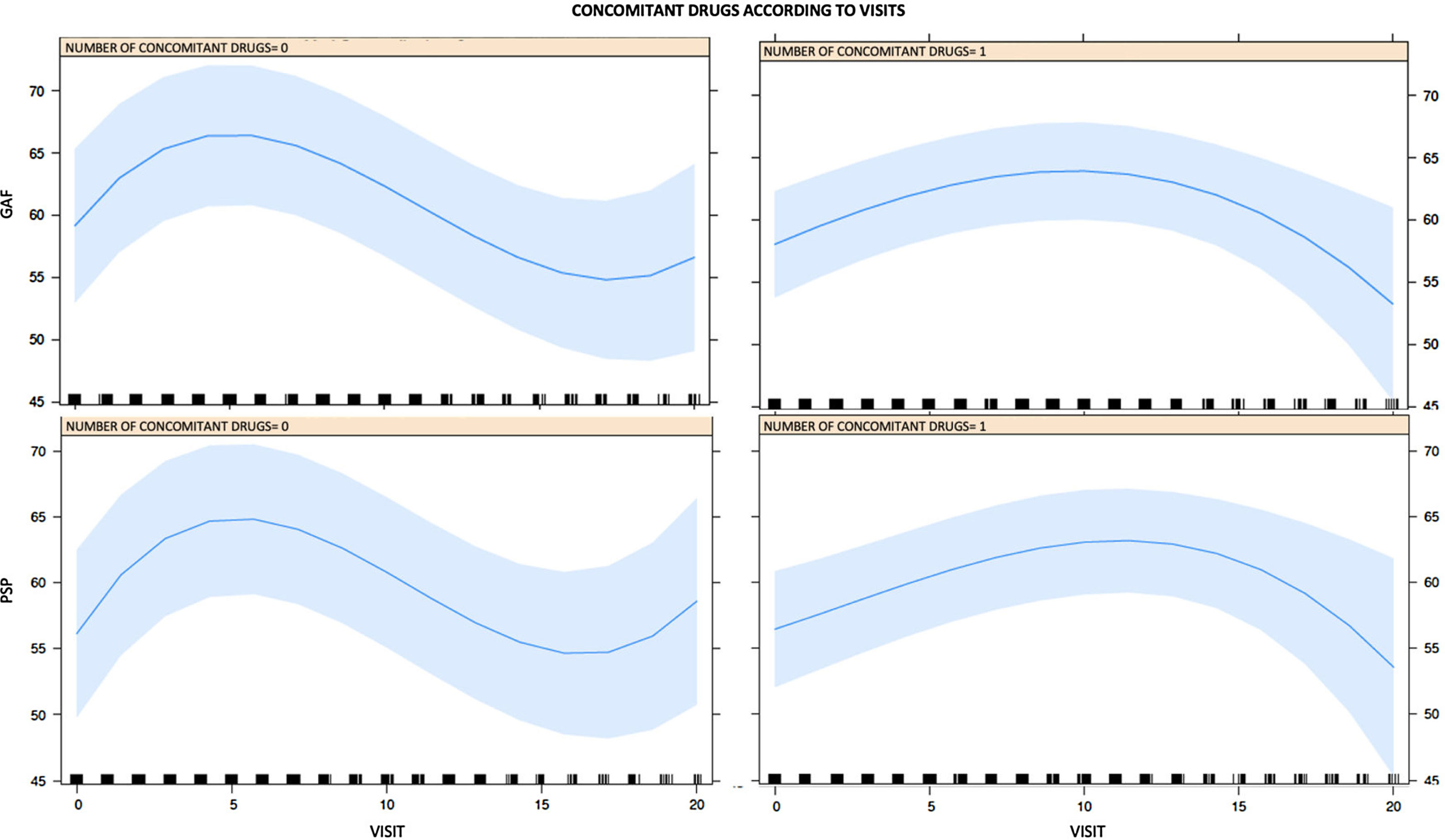

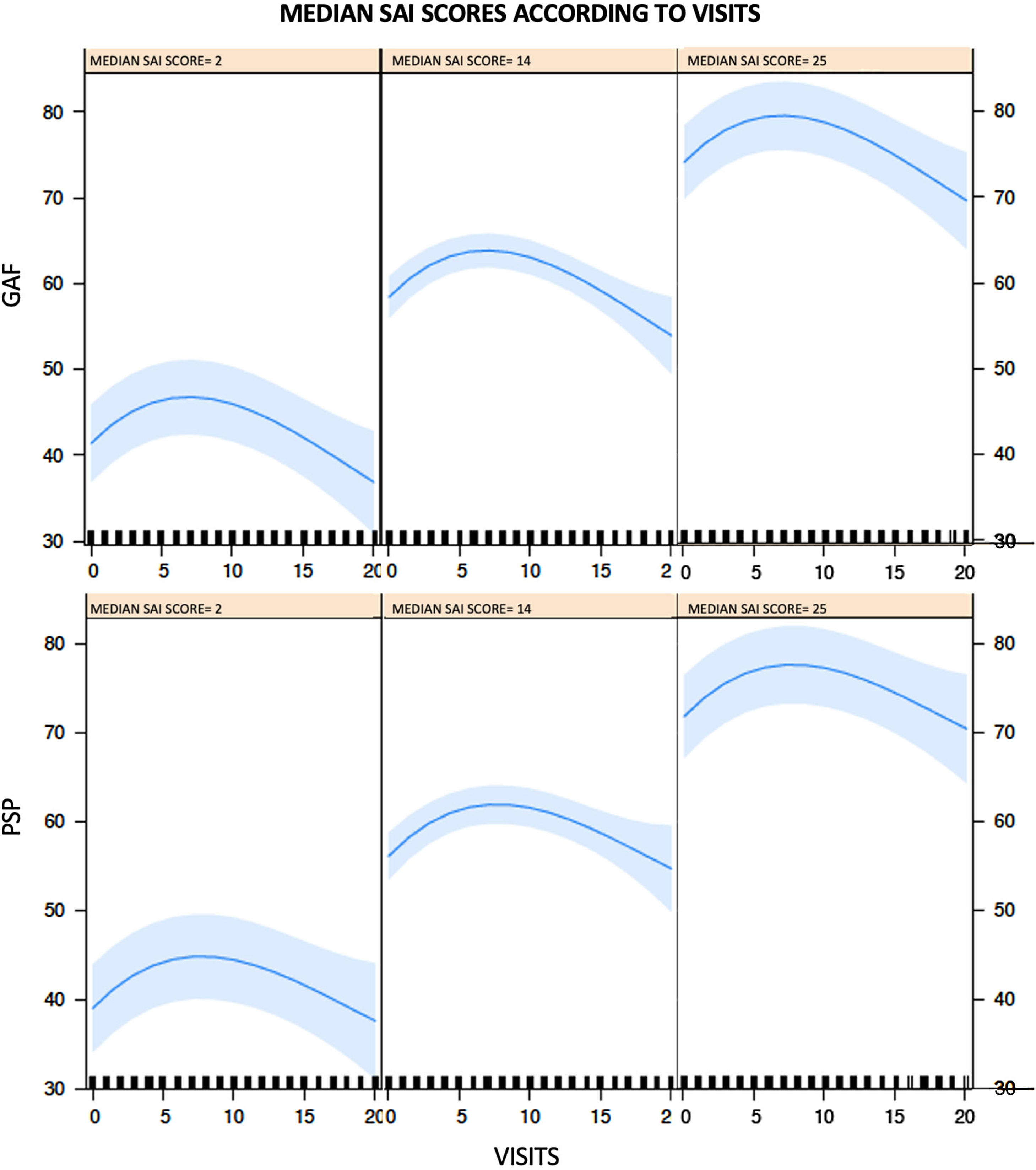

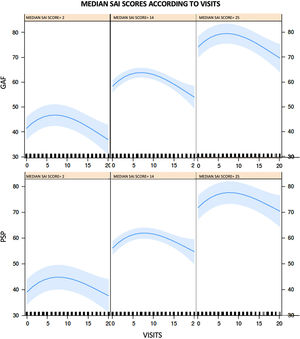

Alternatively, the scores of both scales showed a more marked and earlier decrease in those patients who did not use medications concomitant with antipsychotic treatment. In other words, patients with concomitant medications kept higher and more lasting functionality than those who did not take them (figure 3). Likewise, better median scores in SAI were related to higher scores in GAF and PSP during follow-up (figure 4).

This study aimed to assess the functionality over the first years of schizophrenia. Baseline GAF and PSP scores were between 50 and 60, implying moderate difficulties in occupational or school functioning, social relationships, and self-care. Our results suggest that patients in the earlier stages of schizophrenia have a less than optimal functionality, which seems to be influenced by the number of hospitalization and relapses even a year before. A higher number of relapses is related to a worse overall functionality, and this functional performance tends to be maintained over time. These findings highlight the importance of performing highly personalized, effective, and interdisciplinary interventions at the first years of the illness.

Throughout the first 2 years an improving trend was observed, but after the seventh visit functionality progressively decreased to levels slightly lower than baseline scores. This finding differs from data reported in other studies, where functioning assessment scores tend to increase after 1, 2, or 3 years of follow-up 20,21in both specialized early intervention and naturalistic settings. In fact, the subjects included in our sample failed to achieve the threshold proposed by Albert et al. for recovery (GAF ≥ 60).22

Current evidence indicates that 1 in 7 patients with schizophrenia will achieve functional recovery, mainly based on better social and cognitive functioning after a FEP and not only symptomatic remission.10,23 In fact, functional recovery is influenced by a complex interplay between several environmental factors, including stressful life events, substance abuse, socioeconomic conditions, stigma experiences and family dynamics.24 Therefore, psychosocial and vocational interventions with a strong training in social skills are crucial so the patients can achieve and maintain an independent role in society. It must be noted that non-pharmacological therapies were the exception rather than the rule in this sample. Several clinical trials and systematic reviews support the role of psychosocial interventions (such as cognitive and behavioral psychotherapy, family psychoeducation, and educational and vocational rehabilitation strategies) in structured early intervention programs.25 However, these specialized early intervention services, as well as the community-based programs for schizophrenia, are almost non-existent in Colombia and Latin America.14,26

Most of the patients were using SGAs, which seems to be related to better functional outcomes.27,28 Interestingly, we found some protective role for co-medication as patients with concomitant medications seemed to keep a higher and more lasting functionality over time than those who did not take them. In the case of benzodiazepines, the most used augmentation drug in our study, current evidence is quite conflicting and inconclusive: although its sedative effect could be beneficial during specific lapses in the course of the disorder, its use in the medium and long term is not recommended.29,30 Many of the patients were using other antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and antidepressants as well, but the evidence supporting their efficacy is limited and based on low-quality studies.31–35 It is noteworthy that this tendency to polypharmacy is observed even in the early stages of the disease, which suggests that there are no differential approaches across the stages of the illness in clinical practice in Colombia. Furthermore, there appears to be no direct relationship between the severity of the disorder and the use of polypharmacy which support even more the previous finding. Actually, this finding may suggest that the identification and treatment of affective, anxiety or sleeping symptoms could improve overall functional outcomes, underlining the importance of detecting other mental symptoms in addition to psychosis.

On the other hand, we found a similar pattern in the impact of the number of previous episodes, changes in antipsychotic schemes, number of relapses and hospitalizations in functionality along the first five years of schizophrenia. A higher number of episodes and relapses (and hence, hospitalizations) is expected to lead to more modifications in antipsychotics schemes (change of drugs or use of higher doses), which could, in turn, negatively impact on functionality. Likewise, these changes in pharmacological therapies could also lead to a higher risk of adverse events, impacting on adherence to treatment.

In this study, insight showed a positive effect on functionality. Previous studies have reported that insight is not significantly associated with overall functioning after a FEP, although a significant heterogeneity in measures employed to assess insight has to be noted.36 However, insight is theoretically related with both a better adherence to treatment and a stronger therapeutic alliance, which are in turn associated with better longer-term outcomes in psychosis.37,38

These findings combined may confirm that an integral approach of patients with schizophrenia is required as if we only rely on pharmacological treatments the outcomes won’t be as good as expected. The paucity of specialized early intervention programs for patients in the early stages of schizophrenia in Latin America 26and Spain 39results in a lack of opportunities to change the course of this disorder during a critical time.

Some limitations should be noted. First, the small sample size and the high proportion of men may not reflect the full spectrum of the population accurately and allows only an exploratory analysis of data. In fact, these correlations do not necessarily indicate a causal relationship. Besides, drop-outs during follow-up could affect global results since more seriously ill patients could have tend to continue under monitoring. In addition, depressive or maniac symptoms were not measured, and its presence could have explained polypharmacy in our sample. However, this is one of the few investigations on the early stages of schizophrenia in Colombia, a developing country, which could explain some of the differences with similar studies from other regions.40 Furthermore, its naturalistic design and five years long follow-up bring a more realistic depiction of schizophrenia. Additionally, its prospective design, the strict selection criteria, and the diagnostic and follow-up assessment protocol (that included standardized scales to assess functionality) provided validity to our findings.

In conclusion, our results suggest that patients in early stages schizophrenia show moderate difficulties in global functioning, which although improves temporarily with specialized treatment, defines the overall performance after three to 5 years of follow up. Polypharmacy, degree of insight, modifications in antipsychotic schemes, and number of episodes, relapses, and hospitalizations, are related to global functioning during the first years after diagnosis.

FundingThis research was partly supported by an unrestrictive grant from Janssen-Cilag.

Conflict of interestsAll the authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.